Abstract

Purpose

To assess data about chronic forms of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in Brazilian reference units, the Brazilian Society of Hepatology (SBH) performed a survey, with its associates spread throughout the country.

Methods

SBH members were contacted by electronic mail. They were asked for data from their liver units regarding chronically infected HBV patients between January 2005 and September 2007. All subjects with HBV surface antigenemia lasting more than 6 months were eligible. Patients who died after January 2005 were also included.

Results

Data from 24 units of 17 cities (12 Brazilian states) were obtained. These corresponded to 3,913 patients. Mean age was 39 years, ranging from 1 to 84 years. The northern region had the lowest mean age (35 years) and the southern region the highest (43 years). Most of the sampled people were white; 1,448 of 3,614 patients had chronic hepatitis B. Most of them were HBeAg negative (1.4:1). There were 1,695 (46.9%) inactive carriers of 3,614 HBV-infected patients and other 69 (1.9%) were considered as having immune-tolerant status. Hepatitis D coinfection was common among the Amazonian sample (n = 369).

Conclusions

This large sample study shows important tendencies of chronic hepatitis B infection in Brazilian reference units, such as HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B cases overwhelming wild-type strains infected cases. Besides, hepatitis D occurs only among the Amazonian patients.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis, Hepatitis B virus, Bloodborne infection, Brazil, South America

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is one of the main causes of end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. It is spread worldwide, but presents high prevalence in some regions, such as Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Amazon Basin [2].

Most of the exposed adult individuals develop a strong acquired immune response that controls the infection. However, around 5–10% of them become lifelong HBV carriers [3]. Chronic HBV infection can present different outcomes according to immune and genetic characteristics of the host. Viral factors, such as genotype and viral load, in addition to the age of exposure, also influence the infection outcome.

Most chronic HBV-infected patients have low viral replication with a lack of HBV e antigen (HBeAg) and absence of significant findings from liver biopsy. Generally, these subjects have good outcome and low risk of developing cirrhosis or liver cancer [4]. They are called inactive carriers. On the other hand, there are patients who develop more severe histological lesions and have high HBV DNA levels. These subjects have high risk of developing HBV complications after years or decades of chronic infection. This clinical behavior of HBV infection is called chronic hepatitis.

Classically, chronic B hepatitis is classified into two types according to the presence or lack of HBeAg in the serum. Precore or core promoter mutation eventually arises, precluding HBeAg translation that evades the immune system. Usually, the longer the infection, the greater is the risk of mutant strain emergence [5].

Other presentation of chronic HBV infection is the immune-tolerant phase, which is common among newborns of HBV female carriers. This situation is usually detected among children and teenagers. There is high HBV replication, HBeAg persistence, and high infectivity potential. Liver biopsy shows mild histological activity, and biochemical analysis shows aminotranferase levels under the reference range. However, the prolonged exposure to high HBV DNA levels remarkably increases the risk of HCC development. As a consequence, these patients should be followed under close monitoring. In Brazil, there is a lack of data regarding prevalence of chronic HBV infection forms being followed in liver reference units. To assess these data, the Brazilian Society of Hepatology (SBH) performed a survey, with its associates spread throughout the country. These results were described earlier during the XIX Brazilian Hepatology Meeting, in Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais state, in 2007.

Materials and methods

SBH members were contacted by electronic mail. They were asked for data from their liver units regarding chronically infected HBV patients between January 2005 and September 2007. All subjects with HBV surface antigenemia lasting more than 6 months were eligible. Patients who died after January 2005 were also included. The questionnaire was prepared aiming to get combined information of patients from all the centers, such as percentages of patients with HBeAg or with cirrhosis. Demographic and virological data, such as percentage of each gender, viral load, and genotyping if available, were also collected. Information about probable contagious route was also collected. Some characteristics of each hepatology center were requested, such as whether molecular tests or liver transplant were available. Data from each center were tabulated by the coordination team. Consolidated data of every center were considered by their weight according to the sample size and added to the general data file. As a consequence of the implemented methodology of getting the data, clinical and demographic comparisons among centers were not performed. Descriptive statistics of the overall data was presented. Assessing the results of chronic hepatitis B treatment was not an aim of the study.

Results

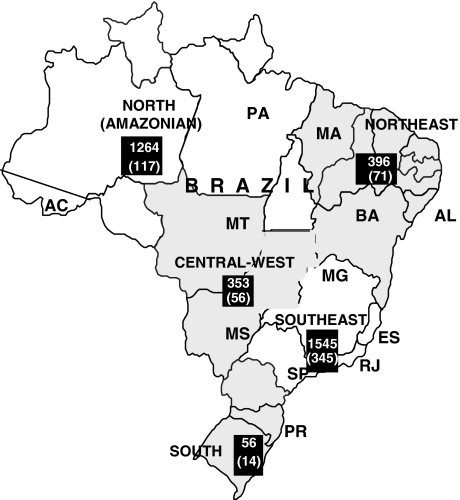

Data from 24 units of 17 cities (12 Brazilian states) were obtained. It corresponded to 3,913 subjects. However, data from only 3,614 patients were appropriate for evaluation. The participants from the southeast region, the most populous, sent data from 1,545 (42.7%) subjects, followed by the northern (Amazonian) region, with 1,267 (35%) patients (Fig. 1). The southern region was represented by a casuistic from a unit of Paraná state and had the smallest sample. Regarding the overall sample, male gender corresponded to 61.2%. Mean age was 39 years, ranging from 1 to 84 years. The northern region had the lowest mean age (35 years) and the southern region the highest (43 years). Most of the sampled people were white (mainly in the southeast and southern regions), followed by mestizo people who predominate in the northern region. Information about skin color was not available from a large proportion of the sample.

Fig. 1.

Brazil map showing the five Brazilian macroregions, the absolute numbers of respective contributions, and number of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis cases (in parenthesis). Participating states abbreviations: AC Acre, PA Pará, MA Maranhão, AL Alagoas, BA Bahia, MT Mato Grosso, MS Mato Grosso do Sul, MG Minas Gerais, ES Espírito Santo, RJ Rio de Janeiro, SP São Paulo, PR Paraná

Cirrhosis was confirmed in 671 (18.5%) patients. HCC was investigated and diagnosed in 70 (2.2%) of 3,102 patients. Among 1,448 (40%) patients with chronic hepatitis B, 603 (42%) patients were HBeAg positive and 845 (58%) anti-HBe positive (Table 1). Hepatic histological results from 41.2% of these patients were available. The mean age of HBeAg-positive patients with chronic hepatitis was 38 years and 24% of them had cirrhosis. Among anti-HBe-positive patients with chronic hepatitis, the mean age was 41 years and 28.7% had cirrhosis. In the northern and southeastern regions, anti-HBe-positive form predominates. HBeAg-positive form prevails in south, northeast, and central west.

Table 1.

Clinical forms of hepatitis B virus chronic infection in Brazilian liver reference units

| Region | Total | HBeAg + CHa (%) | HBeAg − CHa (%) | CH ratiob | Inactive carrier (%) | Immunotolerant | Inactive cirrhosis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | 1,264 | 117 (9.0) | 295 (23.3) | 1:2.5 | 612 (48.4) | 21 (1.6) | 70 (5.5) |

| Northeast | 396 | 71 (17.9) | 28 (7.0) | 2.5:1 | 235 (59.3) | 11 (2.1) | 18 (4.5) |

| C.-West | 353 | 56 (15.9) | 46 (13.0) | 1.2:1 | 207 (55.5) | 10 (2.8) | 34 (9.6) |

| Southeast | 1,545 | 345 (22.0) | 465 (30.1) | 1.3:1 | 618 (43.6) | 26 (1.7) | 91 (5.8) |

| South | 56 | 14 (25.0) | 11 (19.6) | 1.2:1 | 23 (41.0) | 1 (1.8) | 6 (10.7) |

| Totalc | 3,614 | 603 (16.7) | 845 (23.3) | 1:1.4 | 1,695 (46.9) | 69 (1.9) | 219 (6.0) |

aChronic hepatitis

bChronic hepatitis HBeAg+/HBeAg− ratio

cClinical form classification was not feasible according obtained data in 183 (5.0%) out of 3,614 patients

There were 1,695 (46.9%) inactive carriers of 3,614 HBV-infected patients and other 69 (1.9%) patients were considered in immune-tolerant phase. Cirrhosis was diagnosed in 219 (6%) patients. Half of the patients with cirrhosis did not present evidence of HBV replication or necroinflammatory activity.

Among 1,448 patients with chronic hepatitis, 671 (46.3%) took medicines against HBV. Table 2 shows the main drugs used. Analysis of efficacy of the drugs was not a goal of this study.

Table 2.

Drugs used in treatment of 671 patients with chronic hepatitis B in Brazilian liver reference units

| Drug | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Immunomodulators | |

| Conventional interferon alfa | 241 (37) |

| Pegilated interferon alfa | 13 (2) |

| Nucleos(t)ides analogs | |

| Lamivudine | 514 (80) |

| Adefovir | 114 (17) |

| Entecavir | 40 (6) |

Coinfection was present in 479 subjects: 369 (9.4%) with hepatitis delta virus (HDV), 82 (2%) with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and 28 (0.7%) with HIV. Almost all cases of HBV–HDV coinfection were limited to the northern region.

HBV genotyping results from 172 (4.4%) patients were available. These patients were from the following Brazilian states: Acre, in north; Bahia, in northeast; Mato Grosso, in central west; and Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, in southeast. The commonest genotype was A (72%) followed by F (16%) and D (9%). Rare cases of B, C, and E genotypes completed the series (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hepatitis B virus genotyping of 172 patients from Brazilian liver units

| Region | Total | A | B | C | B/C | D | E | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Bahia | 76 | 65 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| Mato Grosso | 16 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Rio de Janeiro | 69 | 45 | 12 | 12 | ||||

| São Paulo | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Total | 172 | 124 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 28 |

Route of infection spread was not known in 61% of the patients. According to the opinion of assistant practitioners, intra-familial transmission was apparently responsible in 17%, vertical route in 8%, and parenteral route in 7%.

Discussion

Hepatitis B virus chronic infection is a major public health problem worldwide because of its complications, such as cirrhosis and HCC. Despite increasing number of papers assessing the prevalence of HBV infection in Brazil and its regional distribution [6–9], there is a lack of information about distribution of clinical forms of HBV chronic infection in the country.

In this report, we confirm that most of the HBV carriers are male, reinforcing that this gender is more susceptible to the chronification of HBV infection [10]. Age ranged broadly, and the mean age was around 40 years in all Brazilian regions, except the northern region (mean age = 35 years). This finding may be attributable to the different epidemiological pattern of HBV infection in Amazon, where HBV exposure takes place earlier than in the other Brazilian regions [11].

In the present study, cirrhosis was diagnosed in 20% of the overall sample. This feature suggests that HBV is a major cause of cirrhosis and its complications in Brazil. This rate ranged from 9% in the northern region to 35% in the southern region. Perhaps, this variation reflects particular characteristics of each center and the epidemiological profile of each region. May be, the youngest sample from the northern region may explain why cirrhosis was less common in that region. The prevalence of HCC was homogenous throughout the regions (2%).

A remarkable finding of this study was that more than half of patients with chronic hepatitis B did not have HBe antigenemia. More recently, there has been a concern that HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B is progressively increasing when compared with HBeAg-positive form. It was estimated to correspond to a third of chronic hepatitis B episodes worldwide in 2000 [5]. Currently, this disease form may predominate worldwide, such as its occurrence in the Mediterranean Basin. This increasing rate of anti-HBe-positive chronic hepatitis B could be explained by some HBV genotypes. For instance, HBV genotype D has high tendency to undergo precore mutation, which avoids HBeAg translation and permits the mutant strain to evade the immune system. Another theory to explain more than half percentage of anti-HBe chronic hepatitis in this sample is that our population is getting older. It has been described that the risk of undergoing precore or core promoter mutation increases along the natural history of the infection [12]. Besides, the present study suggests that the same phenomenon is taking place in Brazil, although it was not found homogenously throughout all regions. The different distribution of HBV wild type and mutant strains among Brazilian regions may be at least, in part, a consequence of different criteria to classify chronic HBV-infected patients. The increasing number of HBeAg-negative patients with chronic hepatitis B in Brazil brings concern to public health in the country. It reinforces the necessity of making quantitative HBV DNA tests available to improve the quality of medical assistance to HBV carriers in Brazil.

Although assessment of HBV treatment results was not an aim of this report, some information about this issue was also obtained. About half of the patients with chronic hepatitis had undergone some treatment. Naturally, the most reported drugs were standard alpha interferon and lamivudine, since both of them are distributed by public health in Brazil. Two-thirds of these patients were lamivudine experimented. These data can work as an alert to public health authorities and to the practitioners who are coping with these patients.

Regarding coinfections, the profile that emerged from this study reflects the large sample coming from the northern region (Amazonian Basin). Coinfection with HIV was not common, likely because infectious disease reference units were not included in this study.

Despite its methodological limitations, the large number of patients censored in the present study with the participation of 12 Brazilian states and 24 units corroborates the importance of this report. Besides, these results should be analyzed carefully because the sample size from each state was not proportional to its population size. Some very populous states and cities, such as Rio Grande do Sul, Pernambuco, and Ceará states and São Paulo city, were not represented. Moreover, some states with small populations, but with high HBV infection prevalence also did not have their units represented.

In this study, data of HBV genotyping were obtained from five Brazilian states and should be analyzed cautiously. Nevertheless, a tendency of genotype A prevailing throughout the whole country was demonstrated in accordance with others reports [8, 13–15]. Genotypes D and F follow genotype A in frequency. Genotype F occurs more frequently in the northernmost part of the country, whereas genotype D is important in the southern part.

In conclusion, this large sample study shows important tendencies of chronic hepatitis B infection in Brazilian reference centers, such as HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B cases overwhelming wild-type strains infected cases, and genotype A as the most frequent genotype among Brazilian patients.

Footnotes

Collaborators by Brazilian states and cities: Acre: Suiane Negreiros (Cruzeiro do Sul), Cirley Lobato, Ana Gurgel, Thiago Araújo, Judith Weirich, Rita Uchoa, Diógenes Dantas, Daniely Gonçalves, Thor Dantas; Pará: Simone Conde, Esther Castelo Branco Miranda, Ivanete Amaral, Manoel Soares, Marialva Araújo, Samia Demachki, Maria Brito, (Belém); Maranhão: Arnaldo Dominici, Adalgisa Ferreira, Márcia Martins, Zeyle Arraes (São Luís); Alagoas: Rosângela Wyszomirska, Vânia Pires, Leila Tojal, Andréia Omena, Fernando Barreiros, Karine Caldas, Thaline Pinto (Maceió); Bahia: André Lyra, Helma Cotrin, Nádia Caldas, Bernardo Salles, Carlos Eduardo Romeu, Bruno Nachef, Carlos Alberto Almeida Filho (Salvador); Mato Grosso: Aline Marques Silva, Francisco José Dutra Souto (Cuiabá); Mato Grosso do Sul: Ivan Reyes Salvador (Campo Grande); Espírito Santo: Carlos Sandoval Gonçalves, Carla Marques, Maria da Penha Zago Gomes (Vitória); Minas Gerais: Cláudia Alves Couto, Osvaldo Flávio Couto, João Galizzi Fº (Belo Horizonte); Rio de Janeiro: Kycia Rodrigues (Petrópolis), Letícia Nabuco, Cristiane Vilela, Renata Perez, Carlos Eduardo Brandão Mello, Flávia Lemos, Jorge André Segadas, Henrique Sérgio Morais Coelho (Rio de Janeiro); São Paulo: Ana Lourdes Martinelli, Sandro Ferreira, Fernanda Fernandes, Andreza Teixeira, Márcia Villanova, Silvana Chacha, José Fernando Figueiredo, Afonso Diniz Passos, Sérgio Zucolotto, Leandra Ramalho, Rosamar Rezende, Ana Tereza Pimenta (Ribeirão Preto), Marília Tavares Gaboardi, Marcelo Mendonça (Osasco), Hoel Sette Jr., Maurício Barros, Celso Metielo (São Paulo), Rita da Silva, Edla Bedin, Armanda Guerra Jr., Márcia Rocha, Patrícia Pereira (São José do Rio Preto); Paraná: Dominique Muzzilo, Ricardo de Bem, Jony Ogata, Cássia Silveira, Caroline Gonzaga, Eleonora Gomes, Ismael Horst Junior, Henrique Stachon, Guilherme Prestes (Curitiba).

Contributor Information

João Galizzi Fº, Email: jgalizzi.bhz@terra.com.br.

Rosângela Teixeira, Email: secdir@medicina.ufmg.br.

José C. F. Fonseca, Email: ppgmcsaude@ufam.edu.br

Francisco J. D. Souto, Email: fcm@ufmt.br

References

- 1.Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection: a review. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733–1745. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chwla Y. Hepatitis B virus: inactive carriers. Virol J. 2005;2:82. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seeger C, Mason WS. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:51–68. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.1.51-68.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manno M, Cammà C, Schepis F, Bassi F, Gelmini R, Giannini F, et al. Natural history of chronic HBV carriers in northern Italy: morbidity and mortality after 30 years. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:756–763. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funk ML, Rosenberg DM, Lok AS. World-wide epidemiology of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B and associated precore and core promoter variants. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:52–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeida D, Tavares-Neto J, Vitvitski L, Almeida A, Mello C, Santana D, et al. Serological markers of hepatitis A, B and C viruses in rural communities of the semiarid Brazilian northeast. Braz J Infect Dis. 2006;10:317–321. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702006000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertolini DA, Pinho JR, Saraceni CP, Moreira RC, Granato CF, Carrilho FJ. Prevalence of serological markers of hepatitis B virus in pregnant women from Paraná state, Brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:1083–1090. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006000800011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bottechia M, Souto FJ, O KM, Amendola M, Brandão CE, Niel C, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and resistance mutations in patients under long term lamivudine therapy: characterization of genotype G in Brazil. BMC Microbiol 2008;8:11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Valente VB, Covas DT, Passos AD. Hepatitis B and C serologic markers in blood donors of the Ribeirão Preto Blood Center. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:488–492. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822005000600008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy MC, Buranurans JP, Constantine NT, El-Hag AAE, El-Tayeb ME, El-Dabi MA, et al. Hepatitis B and HIV in Sudan: a serosurvey for hepatitis B and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies among sexually active heterosexuals. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;41:726–731. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.41.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souto FJ. Distribuição da hepatite B no Brasil: atualização do mapa epidemiológico e proposições para seu controle. Gastroenterol Endosc Digest. 1999;18:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fattovich G. Natural history and prognosis of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:47–58. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomes-Gouvea MS, Soares MCP, Mello IMG, Brito EM, Moia LJP, Bensabath G, et al. Hepatitis D and B virus genotypes in chronically infected patients from the Eastern Amazon Basin. Acta Trop. 2008;106:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribeiro NR, Campos GS, Ângelo AL, Braga EL, Santana N, Gomes MM, et al. Distribution of hepatitis B virus genotypes among patients with chronic infection. Liver Int. 2006;26:636–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sitnik R, Pinho JR, Bertolini DA, Bernardini AP, Da Silva LC, Carrilho FJ. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and precore and core mutants in Brazilian patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;42:2455–2460. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2455-2460.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]