Abstract

Religious congregations are important community institutions that could help fight HIV/AIDS; however, barriers exist, particularly in the area of prevention. Formative, participatory research is needed to understand the capacity of congregations to address HIV/AIDS. This article describes a study that used community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches to learn about congregation-sponsored HIV activities. CBPR strategies were used throughout the study, including proposal development, community expert interviews, Community Advisory Board, congregational telephone survey, congregational case studies, and congregational feedback sessions. Involving community consultants, experts, and advisory board members in all stages of the study helped the researchers to conceptualize congregational involvement in HIV, be more sensitive to potential congregational concerns about the research, achieve high response rates, and interpret and disseminate findings. Providing preliminary case findings to congregational participants in an interactive feedback session improved data quality and relationships with the community. Methods to engage community stakeholders can lay the foundation for future collaborative interventions.

Keywords: Religious congregations, HIV, CBPR, Formative research, Case studies

Introduction

There are more than 300,000 religious congregations in the USA1 and national surveys have found that about half of all adults attend religious services at least monthly.2 Because religious congregations often play important roles in the public realm as well as in the private world of congregants’ lives and values, they are crucial to understanding family, neighborhood, and other mediating structures of empowerment.3 Congregations are often the last to leave distressed neighborhoods, thereby shouldering much of the burden of meeting community needs,4 and they can raise awareness about community problems and resources.5 Congregations also facilitate access to resources such as food, health care, educational and job opportunities, and they provide informal support through extended social networks and linkages with other community institutions.

Because religious congregations reach so many people and have played important roles historically in working for social change, some have concluded that congregations could play a similarly powerful role in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Some Christian and Jewish denominations have issued resolutions to address the AIDS crisis, have established national AIDS ministries, or have participated in interdenominational efforts. However, little is known about the extent to which congregations are involved in HIV/AIDS prevention and care. Only two population-based studies of congregational involvement in HIV/AIDS have been published: (1) a statewide survey in New York (n = 3,218) found that just 16.7% of congregations provided or facilitated HIV/AIDS-related prevention services;6 and (2) a much smaller study (n = 100) in Chicago found that 52% of Latino congregations reported engagement in HIV/AIDS-related activities.7 Both studies identified barriers to congregational involvement in HIV/AIDS, including lack of congregational resources (e.g., qualified staff, clergy training, financial), clergy attitudes (e.g., opposition to homosexuality and bisexuality, drugs, alcohol, or condoms; the belief that HIV/AIDS is not a serious problem in the community), lack of HIV knowledge, and lack of experience with people living with HIV (PLWH).6,7

Descriptive studies of congregation-based HIV prevention efforts have largely focused on the African American community and/or on partnerships between public health entities and individual congregations.8–13 Few articles have examined HIV prevention efforts that congregations have initiated or conducted without external support,14 and few have examined prevention efforts in enough depth to understand the constellation of factors that affect congregational involvement in HIV/AIDS.15,16 Likewise, few articles have focused on congregations’ pastoral care and social support of people with HIV,17,18 although these could be more natural extensions of congregations’ roles and more congruent with their missions and doctrine than many preventive strategies.

Although most of these congregation-based HIV prevention interventions have been developed with substantial input from the faith-based community, it is unclear whether formative data collection or other empirically driven approaches were employed to develop the interventions. Formative research has been identified as critical to understanding the social and environmental context of congregations and designing appropriate congregation-based health interventions.19 To understand better what roles, if any, congregations can play in the fight against HIV/AIDS, research is needed to understand the range of congregational responses to date, where congregations’ capacities and assets are greatest, what challenges have arisen, what strategies have been identified to overcome them, and how these issues vary across congregations of various denominations, faiths, or race–ethnicities. To develop sustainable interventions, participatory approaches that engage local communities are essential.

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is intended to enhance community participation in research and foster community strengths and problem-solving abilities with the goal of taking action.20 CBPR has been defined as “a collaborative approach to research that equitably involves, for example, community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process.”21 In practice, CBPR represents a continuum of participation with considerable range in the roles filled by community members and academic researchers.22

This paper reports on a formative study that used CBPR approaches to better understand the capacity of urban congregations to implement HIV prevention and care activities. The study focuses on congregations in areas of Los Angeles County that have been highly affected by HIV/AIDS and ultimately aims to develop and test a congregation-based intervention addressing HIV/AIDS in collaboration with community partners. However, given the gaps in knowledge regarding congregational involvement in HIV/AIDS, we considered it necessary to first conduct case studies of congregational involvement to inform future interventions and to strengthen our collaborative relationships in the community. Here we describe how we used CBPR to conduct our case studies and to engage community partners, experts, and case study participants, with the goal of improving the quality of our data to develop a collaborative intervention. We conclude with lessons learned that could be useful to others conducting this type of research.

Conceptual Framework

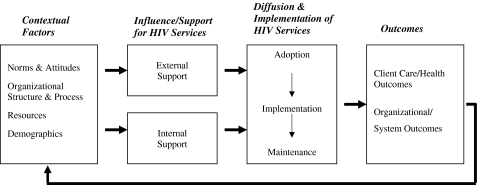

To frame our study, we drew on the diffusion of innovations literature23 and institutional theory, which emphasize the influence on organizations of collective cognitive, normative, and governance systems in the wider social environment, in addition to available technical infrastructure and resources.24,25 Institutional theory takes into account the cultural and constitutive aspects of religious organizations (mission, identity, purpose) that may differentiate congregations from commercial or other types of nonprofit organizations.26

Figure 1 outlines our approach to understanding the factors influencing the adoption and implementation of HIV-related services by religious congregations. The figure identifies four contextual dimensions that affect the willingness and ability of congregations to engage in HIV prevention and care, as well as sources of influence and information.27 Following D’Aunno et al.,28 we highlight the differential effects of internal versus external sources of support to provide HIV-related services.

Norms and attitudes: the extent to which congregations experience social and cultural support for making or resisting changes, including perceptions of need for HIV/AIDS services, stigma or acceptance of HIV/AIDS, and institutional norms for faith-based organizations, such as whether health services are appropriate activities for congregations, and the salience of HIV/AIDS issues to the congregation and community.

Organizational structure and process: the “compatibility” of HIV/AIDS activities23 with the roles of clergy and lay leaders and committees or ministries tasked with organizing social or health programs (internal), and with organized HIV and other health services in the community (external) and the ways in which congregant leaders and community health services interact.

Congregation resources: the ability to mobilize resources from within congregations or wider environments,29 including various forms of “capital”, such as financial, physical (e.g., building space), human (e.g., staff, volunteers), social, and political capital (i.e., congregations’ and congregants’ relationships to others in the community or beyond).30

Congregation demographics: the ethnic/racial, income, educational, and health composition of congregations and community settings, which affects the need for HIV/AIDS services in the congregation, the availability of resources, and local community norms and attitudes.

FIGURE 1.

Diffusion and implementation of HIV-related services among religious congregations in local community settings.

We expected to refine the framework as our understanding of congregational involvement in HIV/AIDS issues deepened as a result of our qualitative research, thereby providing a firm conceptual basis for designing a community-based health intervention.

Study Approach

We used CBPR approaches in each stage of our study: proposal development, community expert interviews, community advisory board, congregation screener survey, selection and recruitment of congregation case studies, case study data collection, and congregation feedback sessions.

Proposal Development

The proposal for this study responded to a special program announcement on religious organizations and HIV from the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). We focused on Los Angeles County because: (1) it is the second-largest AIDS epicenter in the USA; (2) preliminary investigation suggested that congregational responses varied widely; and (3) the local health department had been trying to spur faith-based action through a funding initiative. We used county health data on HIV/AIDS to identify the three geographical areas of Los Angeles County most highly impacted by HIV.

Building on investigators’ existing relationships with a broad range of stakeholders in our study area, we obtained input on our proposal from leaders and representatives of faith-based organizations and public health/HIV agencies, including local county and city health departments, HIV service providers, clergy associations, a hospital-based health and faith partnership, local networks of congregations, and prominent religious leaders. Many of these individuals later participated in community expert interviews, and some agreed to serve on the study’s Community Advisory Board (CAB) or in other advisory or support capacities. Two ordained ministers who together brought a wealth of experience on congregational capacity, African American and Latino religiosity, and congregation-based health and HIV/AIDS activities, agreed to serve as paid co-investigators and co-chairs of the Community Advisory Board (described below). The rest of the research team was diverse racially and ethnically, brought various disciplinary and substantive expertise (public health, social psychology, organizational sociology, survey research), and possessed appropriate language and cultural skills for working with diverse communities.

Community Expert Interviews

We conducted semi-structured interviews with local religious and public health leaders who were knowledgeable about congregations and HIV/AIDS to develop our case study sampling frame and explore aspects of our conceptual framework.

To select community expert participants, we compiled a list of 26 possible interviewees through our community consultants and other contacts. We then selected a purposive sample of 20 experts who reflected the range of diversity desired, such as race/ethnicity, gender, and professional background (religious leader vs. public health or HIV service provider). After initial contact via telephone or email, we obtained verbal consent prior to commencing the in-person interviews, which were conducted by two researchers with the assistance of a note-taker. The detailed notes were reviewed and augmented by the researchers who conducted the interviews, then analyzed by the larger research team to extract and organize themes identified from across the interviews according to the three main topic areas of the interview guide: (1) involvement of religious congregations in health and HIV/AIDS issues (e.g., who gets involved, how these activities tend to be organized within congregations, differences among religious denominations), (2) characteristics of the study communities, and (3) specific congregations involved in HIV/AIDS.

Table 1 provides an overview of the 17 participants (three were unable to participate due to time constraints). Over two-thirds (70%) of the participants were religious leaders (clergy or lay) and of those, nearly one-third represented Mainline Protestant denominations (African Methodist Episcopal, Episcopal, Lutheran, United Methodist), with the rest equally distributed among Catholic, Evangelical, Jewish, and Muslim denominations. Participants were nearly equally distributed in terms of race–ethnicity (29% African American, 29% Latino, and 35% White). Ten were men and seven were women.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics of community expert interviews (n = 17)

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Public health leader | 5 (29) |

| Religious leader | 12 (70) |

| Mainline Protestant | 4 |

| Evangelical/Pentecostal | 2 |

| Catholic | 2 |

| Jewish | 2 |

| Muslim | 2 |

| Male | 10 (59) |

| Race–ethnicity | |

| African American | 5 (29) |

| Latino | 5 (29) |

| White | 6 (35) |

| Other | 1 (7) |

In addition to suggesting specific congregations involved in HIV/AIDS in our study areas, community experts highlighted the importance of many factors that can affect congregational participation in HIV/AIDS activities. First, organizational structure and linkages—e.g., having bishops and cardinals that can exert their influence over congregations or autonomous congregations in which authority is at the local level—can influence whether and how congregations become involved in HIV/AIDS. Furthermore, congregations linked into wider denominational structure often have access to external resources, whereas locally controlled congregations may be involved in such activities only if they have enough internal resources. Second, the degree to which congregations and/or their leaders are “inwardly” vs. “outwardly” focused—i.e., concerned with the congregation and/or spiritual issues vs. the broader community and/or on material/social issues—can influence how open congregations are to addressing health issues. Third, whether congregational leaders have a personal connection to HIV/AIDS through other members, family, or close friends is a strong motivator of congregational activity. Finally, many religious leaders are reluctant to address HIV/AIDS because of its association with behaviors that are not consistent with religious teachings (e.g., drug use, male to male sex).

Community Advisory Board

CABs have been proposed as a way to formalize the involvement of the community in the research process and thereby improve the informed consent process, study design, and implementation;31 they have been extensively used in AIDS-related research.32 Our CAB includes both community experts we interviewed and other religious and health leaders suggested by the interviewees. Throughout the study, we met in person with our CAB every 3 to 4 months and communicated with CAB members between meetings as needed.

The CAB was instrumental in helping us select congregations, refine data collection tools and processes, troubleshoot, interpret preliminary findings, and disseminate results. For example, during presentation of preliminary case study findings, CAB members provided invaluable insights on the framing and formatting of results to more fully engage participants in the Congregational Feedback Sessions (described further below). Like the research team, CAB members signed an agreement to protect the confidentiality of case study participants.

Congregation Screener Survey

Through the community expert interviews, our CAB, and other sources, we compiled a list of 80 congregations potentially involved in HIV/AIDS in our study area. To select our case studies, our CAB helped us develop a brief screening questionnaire that was administered by telephone. The interview covered three main topics: (1) health and HIV/AIDS activities conducted, whether they are current, and how they are/were organized; (2) congregational size and racial and ethnic composition; and (3) denomination (if any). We attempted to contact the senior clergyperson to complete the survey, but if she/he were not available, we spoke with associate clergy or another staff member. Seven of the congregations were eliminated because the telephone number was no longer in service. For the remaining 73 congregations, we were able to complete the screening questionnaire with 64 (88%); the other nine (12%) did not respond to repeated attempts (five calls) to contact them. It took on average two to three attempts or calls (range 1–5) to complete the survey at each congregation. Of the 64, most (47 or 73%) were completed by clergy, with the remaining completed by other church staff (church secretaries and administrators, AIDS program staff, parish nurses, and librarians). We used the data from the congregation screener survey to select a purposive sample of congregations that varied in size, denominational group, racial/ethnic composition, and level of HIV/AIDS activity (including some very low or “no activity” congregations).

We had planned to use a dichotomous definition of HIV/AIDS activity (active vs. not active), in a matched-case study design. However, our CAB members’ insights led us to reconceptualize congregational involvement in HIV/AIDS as a continuum and to recognize that congregational involvement with HIV has changed over time as the epidemic has changed. We therefore focused on identifying the range of formal and informal HIV/AIDS activities conducted by and in congregations and how these have changed over time. We also characterized congregations according to their activity levels, so that we could recruit case study congregations that represent a broad range. Table 2 provides an overview of how we categorized various congregations into high, medium, low, and no or latent activity levels based on the frequency and type of activities (latent means previously active). The examples of activities for each level are illustrative, i.e., they show which activities were most associated with each level. Congregations that conducted activities illustrative of more than one activity level were classified at the highest level for the range they reported.

Table 2.

Examples of representative congregational activities at high, medium, and low HIV/AIDS activity levels

| Level | Definition | Examples of prevention and awareness activities | Examples of support and care for PLWH |

|---|---|---|---|

| No or latent activity | Congregations not currently involved in HIV/AIDS services and/or activities | N/A | N/A |

| Low level of activity | Activities are infrequent (e.g., once a year event) or are not targeted specifically to HIV/AIDS | Annual worship services highlighting HIV/AIDS (World AIDS Day, annual AIDS mass) | Food banks |

| Health fairs | |||

| Medium level of activity | Activities are more frequent than once a year and may target HIV/AIDS, but are an extension of the types of activities that congregations already do | Disseminating educational material | Pastoral care and spiritual counseling |

| Guest speakers | Social referral service | ||

| Mentoring programs/youth groups | Providing transportation to medical appointments, etc. | ||

| Pastor speaks openly about HIV/AIDS during sermon | Raise money through AIDS walk | ||

| High level of activity | Activities are frequent, target HIV/AIDS, and include multiple types of activities that can be considered above and beyond what congregations traditionally do | HIV testing | HIV/AIDS support groups |

| HIV/AIDS workshops/seminars/classes | Spiritual retreats for PLWH | ||

| Participate in community forums and town hall meetings on HIV/AIDS | Visit an AIDS hospice | ||

| Educate congregants to reduce stigma and increase awareness | Deliver/prepare food for PLWH | ||

| Participate in inter-faith network on HIV/AIDS | Distribute personal care products to PLWH |

Selecting and Recruiting Congregation Case Studies

After completing our congregation screener survey, we reviewed the results with our CAB and identified priority congregations for case study recruitment. Our CAB assisted us in identifying additional congregations of the types that were lacking. Recruitment of congregations required extensive contacts involving both the research team and the CAB. These activities consisted of: (1) a mailing with a study brochure and a letter addressed to the principal clergy leader and signed by the principal investigator, outreach director, and the two CAB co-chairs that invited the congregation to participate; (2) a call made by a CAB member encouraging the clergy leader to consider participating; (3) a call from a research team member to set up a recruitment meeting; (4) a recruitment meeting with the clergy leader and others she/he deemed appropriate; (5) subsequent follow-up as appropriate to plan data collection; and (6) signing of a participation agreement which outlined the roles and responsibilities of research team members and congregation participants. Each congregation received a financial donation for participating. The timeline for recruitment varied across congregations. Some clergy responded immediately after receiving the invitation letter and signed the participation agreement at the first (and only) recruitment meeting and others agreed to participate only after the team made multiple meetings and visits to congregation worship services. For nearly all the recruited congregations, CAB members’ endorsements were instrumental in helping us gain entrée.

Table 3 provides an overview of the 14 congregations that were recruited successfully. Three additional congregations that were invited did not participate—one because of “competing congregational activities,” a second because the congregation was between pastors, and the third did not give a reason. Of the participating congregations, we categorized six in the “high” activity level, four in the “medium” level, and four in the “low/no/latent” level. Six of the congregations were predominantly African American (≥70%), four were predominantly Latino (three Spanish-speaking and one English speaking), two were predominantly white, and two were of mixed race–ethnicity, where no one race–ethnic group represented more than 70%. Of the denominational groups, five were either Evangelical, Pentecostal, or non-denominational, four were Mainline Protestant, three Roman Catholic, and two Jewish (Reform). We were not able to identify any Muslim congregations currently involved in HIV/AIDS, either through our community expert interviews with Muslim leaders or the congregational screener survey.

Table 3.

Level of HIV/AIDS activity, denomination, race–ethnicity, and congregation size of recruited case studies (n = 14)

| Denominational group | High | Medium | Low/no/latent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic | African American/Latino (1,000) | Latino (12,000) | |

| Latino/White (1,500) | |||

| Baptist/Evangelical/Pentecostal/Non-denominational | African American (300) | Latino (900) | Latino (200) |

| Mixed (70) | African American (350) | ||

| Mainline Protestant | Mixed (250) | African American (100) | African American (350) |

| African American (150) | |||

| Jewish | White (500) | White (900) |

Case Study Data Collection

Data were collected on a rolling basis over approximately a 1-year period at each congregation, using the following sources: (1) recruitment meetings where details about study participation were discussed and initial background about the congregation obtained; (2) interviews with clergy and lay leaders covering leaders’ background and experience, congregational background and dynamics, congregational involvement in health and HIV/AIDS activities, denominational and congregational policies, leader and congregational attitudes, community characteristics and collaborations, and perceptions of overall role of the faith community in HIV/AIDS; (3) congregation information form about congregational membership, resources, and programs or ministries; (4) observation of religious services; (5) health and/or HIV activity observations; (6) field observations (physical structure, neighborhood); and (7) review of archival information about the congregation and its health and HIV/AIDS activities.

Our CAB provided feedback on all data collection instruments and gave us guidance on appropriate handling of other aspects of the case study methodology, such as monetary incentives, participants’ receptivity to being audio-recorded, and topics that represented potentially sensitive issues for different types of congregations. The case study interviews with clergy and lay leaders were audio-recorded and transcribed; we also took extensive notes for interviews and all other interactions and observations at congregations (i.e., recruitment meetings, and the religious service, health/HIV activity, and field observations).

We created case summaries that triangulate data from these sources to give an overall picture of each case, focusing on its health and/or HIV/AIDS “story,” including the principal drivers of and challenges to developing and sustaining these activities over time. We validated each case summary by presenting it to congregational leaders for feedback, as described below. In addition, we coded interview transcripts to identify prominent themes from cross-case analysis. Our extensive coding tree is based on a case study interview guide (developed from the community expert interviews in collaboration with our CAB). We identified emergent codes through iterative team discussions to consensus.

Beyond yielding rich data on each congregation, the intensive process of case data collection over a year-long period and the fact that the research focused on learning from congregations served to build trust, lasting relationships, and interest in the research on the part of congregations. This form of case study methodology can be highly conducive to a CBPR approach with the aim of developing appropriate interventions, a feature further reinforced through the congregational feedback sessions.

Congregational Feedback Sessions

The case study participation agreement specified our commitment to provide an initial summary of the congregation’s involvement in health and HIV/AIDS to congregational leaders to allow them to validate, fact-check, and otherwise ensure that we had accurately captured the congregation’s “story” before we moved forward with analysis. We provided this feedback in meetings scheduled at each congregation’s convenience that lasted from 1 to 2.5 h. The main discussion document distributed at the feedback sessions was a case summary (as a PowerPoint presentation) that included preliminary observations about the congregation’s history, demographics, clergy, and lay leadership; characteristics of the community served; activities related to health and HIV/AIDS; reflections on the congregation’s “story” (including drivers and challenges to health and HIV/AIDS work); and leader perspectives of the faith community’s role in HIV/AIDS; we also included specific questions for clarification and discussion. We also distributed: (1) informational handouts that were developed in collaboration with a CAB subcommittee and customized for each congregation with data on neighborhood demographics, local health care access, local AIDS cases burden and composition, and local HIV/AIDS resources; and (2) HIV resource guides developed by the local county health department (www.hivla.org).

Overall, the feedback sessions were very beneficial to the study and the participating congregations. The process to develop the summaries and the thorough vetting by research team members and input from our CAB helped us see emerging themes about each congregation’s “story.” Congregational leaders appreciated the opportunity to review and respond to our initial analyses, as well as to reflect on their own experiences. Both points of clarification and new information were offered. The areas most frequently corrected by congregants were congregation size and demographic composition; programs that were in place but not discussed in original interviews (e.g., jail ministry, domestic violence awareness raising efforts); and clarification of congregational priorities and how they relate to one another (consensus on which appeared to be facilitated in several cases by the group format of the feedback sessions).

Many congregations reported additional benefits to the feedback presentations, e.g., educating new members about the congregation’s history of involvement in health and HIV/AIDS or obtaining a summary of their prior efforts for use in grant proposals and planning future activities. Some congregations subsequently reported making changes to their AIDS ministries or committees in response to what they had learned through the data collection process. For example, one congregation that had recently seen a decrease in their once-extensive HIV/AIDS involvement reported that they had experienced resurgence in leadership and volunteerism for such activities after participating in the study. Another congregation that had not been previously engaged in HIV/AIDS added HIV testing to their annual health fair.

Lessons Learned

Addressing HIV-related health needs through congregations poses unusual challenges for potential partners such as public health departments or academically based interventionists. While many congregations may be receptive to standardized health interventions on less sensitive topics such as blood pressure screening, HIV/AIDS and associated risk behaviors are highly sensitive topics. Because of this sensitivity, HIV-related interventions that involve collaboration between congregations and outside organizations must be highly collaborative and built on a foundation of trust. The research methods we employed in studying congregations’ involvement in HIV/AIDS-related activities in these 14 case studies drew on methods used in CBPR. These methods proved effective in achieving both the aims of our formative research and in establishing relationships conducive to future collaboration to design interventions that have congregational support and are appropriately tailored to specific congregational settings.

CBPR includes a broad set of approaches to community collaboration, and we employed many of these studying congregations’ involvement in HIV/AIDS activities. Here we highlight some key lessons learned from our experience.

Involving congregational leaders as consultants and CAB members in early stages of the research was essential. The community consultants helped craft the proposal, strongly suggesting that we explore congregational HIV/AIDS and health activities to make it easier for some congregations and/or leaders to be receptive to the study. The participation of religious leaders as community experts and CAB members allowed us to learn more about congregations and their HIV/AIDS activities. Participation of local health departments and AIDS service organizations in our CAB provided important perspectives of potential partners for congregation-based interventions, particularly since partnerships between public health entities and congregations have been identified as key to developing faith-based HIV/AIDS programs.7,8,15

The participation of the CAB has been key throughout the project, helping us shape the conceptual framework for the project and conceptualize the full spectrum of ways in which congregations might be involved in HIV/AIDS activities. The CAB also helped us develop a focused and appropriate set of interview questions and advised us on approaching congregations, providing incentives, and collecting the data in such a way as to minimize respondent discomfort and burden. They also helped us better understand community context and congregations to include as case studies. They became strong advocates for the project, helping convince some leaders to participate and informing others in their network about the study.

Although the CAB made invaluable contributions, involving CAB members meaningfully in our study has come with some challenges. One challenge has been getting all members to attend every meeting, given the demands on their time. We found that offering the possibility of telephone conferencing instead of in-person attendance facilitated the participation of some members, as did allowing members to send a designated delegate. Several CAB members changed jobs during the study, which raised the question of whether the membership belonged to the individual or the organization. We did allow for replacements and delegates to attend but this became more difficult the further we got into the study.

Our commitment to provide preliminary results to congregational participants improved our data quality and community relationships. The feedback sessions corrected inaccurate information, provided additional information, and stimulated congregational reflection. However, the time required to prepare for and schedule feedback sessions was substantial. We estimated that these sessions lengthened our overall project timeline by at least 9 months. Nonetheless, these kinds of investments are important, particularly for community-based studies that intend to ultimately lead to action. The congregation feedback sessions also allowed us to learn about additional developments in congregational HIV/AIDS activities that occurred after data collection had been completed. Several of these activities seem to have been a result—direct or indirect—of congregations’ participation in the study.

Finally, we must acknowledge the challenge of building true partnerships with grant funding. Adequate and flexible funds are needed to support the front–end investments in community-researcher relationship-building as well as the extra time often needed as the community participation process unfolds.33 We are fortunate to have continued funding with which we can now develop an intervention with community partners that can be informed by the case studies. However, sustaining partnerships beyond the funding period of the grant is one of the biggest concerns for both communities and researchers.34 The most critical underlying dimension of sustainability is the building of lasting relationships built on mutual trust and commitment among collaborative partners.35 Indeed, the more extensive forms of CBPR in which community members share responsibility and participate in all phases of the design, implementation, and analysis of the research, are predicated on such trust and relationships that heighten mutual commitment, increase the search for common understanding, and help to resolve the inevitable differences that arise when stakeholders with diverse sets of backgrounds and interests work together. These issues are particularly salient in partnerships between researchers and faith-based organizations that do not share a long history of collaboration, and this is even more the case for HIV/AIDS and other issues that are sensitive topics in many minority communities.

Strong and trusting relationships do not materialize overnight, but take time and effort of all parties to cultivate. This study demonstrates that a range of methods and strategies can be used to engage community stakeholders—including on-going involvement of CAB members, consultation with community experts, and reciprocal interaction with research participants—that can lay the foundation for authentic and sustained joint development of health promotion interventions with key stakeholders in underserved communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Grant Number 1 R01 HD50150 from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD. The authors thank RAND colleagues who assisted with data collection activities: Blanca X. Domínguez, M.P.H.; Kartika Palar, M.A.; and Lizeth Bejarano. Dennis E. Corbin, Ph.D., M.S.W. of California State University–Dominguez Hills also assisted with the case studies. Kristin Leuschner, Ph.D., of RAND provided very helpful comments on the manuscript. In addition, we are grateful for the substantial contributions of our Community Advisory Board and community experts, and for the 14 congregations that participated as case studies.

References

- 1.Chaves M. Congregations in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Idler EL, Musick MA, Ellison CG. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research: conceptual background and findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Res Aging. 2003;25(4):327–365. doi: 10.1177/0164027503025004001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger PL, Neuhaus RJ. To Empower People: the Role of Mediating Structures in Public Policy. Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foley MW, McCarthy J, Chaves M. Social capital, religious institutions, and poor communities. In: Saegert S, Thompson JP, Warren MR, editors. Social Capital and Poor Communities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans SM, Boyte HC. Free Spaces: The Sources of Democratic Change in America. 1. New York: Harper & Row; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tesoriero JM, Parisi DM, Sampson S, Foster J, Klein S, Ellemberg C. Faith communities and HIV/AIDS prevention in New York State: results of a statewide survey. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(6):544–556. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.6.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernández EI, Burwell R, Smith J. Answering the Call: How Latino Churches Can Respond to the HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Institute for Latino Studies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agate LL, Cato-Watson D, Mullins JM, et al. Churches United to Stop HIV (CUSH): a faith-based HIV prevention initiative. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(7 Suppl):60S–63S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin J, Daley E, Brown E, et al. Knowledge and perception of STI/HIV risk among rural African-American youth: lessons learned in a faith-based pilot program. J HIV AIDS Prev Child Youth. 2008;9(1):97–114. doi: 10.1080/10698370802175193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus MT, Walker T, Swint JM, et al. Community-based participatory research to prevent substance abuse and HIV/AIDS in African-American adolescents. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(4):347–359. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacMaster SA, Jones JL, Rasch RER, Crawford SL, Thompson S, Sanders EC. Evaluation of a faith-based culturally relevant program for African American substance users at risk for HIV in the southern United States. Res Soc Work Pract. 2007;17(2):229–238. doi: 10.1177/1049731506296826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merz JP. The role of churches in helping adolescents prevent HIV/AIDS. J HIV/AIDS Prev Educ Adolesc Child. 1997;1(2):45–55. doi: 10.1300/J129v01n02_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyrell CO, Klein SJ, Gieryic SM, Devore BS, Cooper JG, Tesoriero JM. Early results of a statewide initiative to involve faith communities in HIV prevention. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(5):429–436. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000333876.70819.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown EJ, Williams SE. Southern rural African American faith communities role in STI/HIV prevention within two counties: an exploration. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2005;4(3):47–62. doi: 10.1300/J187v04n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hicks KE, Allen JA, Wright E. Building holistic HIV/AIDS responses in African American urban faith communities: a qualitative, multiple case study analysis. Fam Community Health. 2005;28(2):184–205. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200504000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leong P. Religion, flesh, and blood: re-creating religious culture in the context of HIV/AIDS. Sociol Relig. 2006;67(3):295–311. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham SD, Kerrigan DL, McNeely CA, Ellen JM. The role of structure versus individual agency in churches' responses to HIV/AIDS: a case study of Baltimore City Churches. J Relig Health, Aug 28 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Shelp EE, DuBose ER, Sunderland RH. The infrastructure of religious communities: a neglected resource for care of people with AIDS. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(8):970–972. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.80.8.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minkler M. Using participatory action research to build healthy communities. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(2–3):191–197. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green LW, Mercer SL. Can public health researchers and agencies reconcile the push from funding bodies and the pull from communities? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1926–1929. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott WR. Institutions and Organizations. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell WW, DiMaggio P. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chin JJ, Mantell J, Weiss L, Bhagavan M, Luo X. Chinese and South Asian religious institutions and HIV prevention in New York City. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(5):484–502. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.5.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendel PJ, Meredith LS, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Interventions in organizational and community context: a framework for dissemination in health services research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(1–2):21–37. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Aunno T, Vaughn TE, McElroy P. An institutional analysis of HIV prevention efforts by the nation's outpatient drug abuse treatment units. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(2):175–192. doi: 10.2307/2676372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarthy JD, Zald MN. Resource mobilization and social movements: a partial theory. Am J Sociol. 1977;82:1212–1241. doi: 10.1086/226464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin N, Cook KS, Burt RS. Social Capital: Theory and Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strauss RP, Sengupta S, Quinn SC, et al. The role of community advisory boards: involving communities in the informed consent process. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1938–1943. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox LE, Rouff JR, Svendsen KH, Markowitz M, Abrams DI, Beirn T. Community programs for clinical research on AIDS. Community advisory boards: their role in AIDS clinical trials. Health Soc Work. 1998;23:290–297. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.4.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1210–1213. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srinivasan S, Collman GW. Evolving partnerships in community. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(12):1814–1816. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004. [Google Scholar]