Abstract

Cell migration is a central process that is essential for embryonic development, wound repair, inflammatory response, homeostasis and tumor metastasis. A method of genome-wide selection based on the gain-of-function has been devised to identify novel cell migration-promoting genes in cultured cells. After the introduction of the retroviral mouse brain cDNA library into NIH3T3 mouse fibroblast cells, migration-promoted cells were selected by a three-dimensional migration assay using cell culture inserts. After five rounds of enrichment, cDNAs were retrieved from the cells that passed the selection processes. Cell migration-promoting activity was confirmed by independent migration assays for the retrieved cDNAs. Multiple cell migration-promoting genes were successfully isolated by this method. The genes identified can be used to gain a systematic view of cell migration. The gain-of-function selection method described here can be combined with RNAi-mediated loss-of-function screen or selection to be a more powerful tool for the systems biology research of cell migration.

Key words: cell migration, functional selection, retroviral cDNA library, gain-of-function, systems biology, RNAi screen

Cell migration is essential for a number of biological processes such as embryonic development, wound repair, inflammatory response and tumor metastasis.1–3 Cell migration is considered as a complex and highly coordinated process that involves the formation of extended protrusions in the direction of migration, and it is driven by actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesion.4 Cell migration is believed to be under the control of complex regulatory mechanisms that are likely to be mediated by numerous genes. In order to identify novel genes that regulate the process of cell migration, we utilized an in vitro functional selection of a cell migration phenotype following introduction of a retroviral cDNA library. The unbiased selection procedure successfully identified multiple migration-promoting genes.

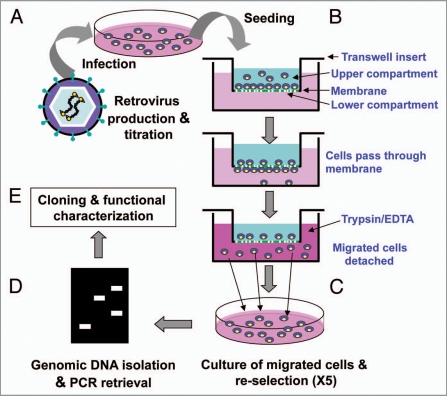

The genome-wide selection process is schematically illustrated in Figure 1. NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were infected with a retroviral mouse brain cDNA library at MOI of 1. Two days post-infection, cells were seeded onto the upper face of the transwell culture inserts (upper compartment) and allowed to migrate through the membrane to the lower face of the transwell culture inserts (lower compartment) for 5 h. Migrated cells were isolated by detaching them from lower face of the transwell culture inserts or bottom of culture well. Detached cells were re-seeded onto the upper face of the transwell culture inserts, which were then allowed to migrate through the membrane again for enrichment. This process was repeated five times. After the final round of enrichment, migrated cells were expanded into individual clones through the limiting dilution, from which genomic DNA was extracted. Chromosomally integrated library cDNAs were PCR-amplified using specific primers and identified by sequence determination. DNA sequencing revealed that 10% of the identified cDNAs were previously reported to be related with cell migration. The remaining cDNA clones included genes without a previous implication in cell migration or partial cDNAs that are thought to be a false positive. A part of the cDNAs identified was subjected to the further investigation: these are Cyth2 (cytohesin2), Chchd2 (coiled coil helix coiled coil helix domain-containing 2), Arpc3 (actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 3), CtsB (cathepsin B), Nrsn-1 (neurensin 1), Tubb2a (tubulin, beta 2a), Ubl7 (ubiquitin-like 7), ZH10 (similar to protein C14orf111 homolog), Anapc5 (anaphase-promoting complex subunit5), Sparcl1 (SPARC-like 1), LOC100045322 (Mus musculus similar to 37 kDa oncofetal antigen) and Myl6 (myosin, light poly-peptide 6). Cell migration-promoting activity of these cDNAs was individually tested by transient expression. The cDNAs were cloned into pcDNA3 then transiently transfected into NIH3T3 fibroblast cells or HEK293 epithelial cells. After confirming the expression of the transiently transfected cDNAs, migration activity of transfectants was assessed by three-dimensional cell migration assay using transwell culture inserts; all cDNAs tested showed varying degrees of promigratory activity (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of novel gain-of-function in vitro selection for the cell migration-promoting genes. (A) A retroviral cDNA library was generated by transient transfection of Phoenix Eco packaging cells with ViraPort® XR Mouse Brain cDNA Library (Stratagene). Cell-free supernatants were harvested 2 days post-transfection and subsequently used to infect NIH3T3 fibroblast cells at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. (B) Two days post-infection, cells were seeded (4 × 104 cells/well) onto the transwell culture inserts and incubated at 37°C for 5 h. Migrated cells were collected by trypsinization of the cells adhered to the lower face of the transwell culture inserts or the bottom of the plates, and re-seeded onto the transwell culture inserts. Cells were then allowed to migrate again for enrichment, which was repeated five times. (C) After the final round of enrichment, migrated cells were expanded into individual clones by limiting dilution. (D) The chromosomally integrated cDNAs were identified by PCR followed by sequencing. The cDNA segments were amplified by using the primers that are specific for regions flanking the multiple cloning site of the retroviral vector. (E) Finally, identified cDNA fragments were cloned into pcDNA3 and further analyzed.

Table 1.

Genes identified in the migration screen and their promigratory activity

| Name | Accession no. | Remarks | Percent increase of migration |

| Cyth2 (cytohesin2) | NM_011181 | Arf guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor | 185 ± 10 |

| Chchd2 (coiled coil helix coiled coil helix domain-containing 2) | NM_024166 | Unknown | 163 ± 12 |

| Arpc3 (actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 3) | NM_019824 | Actin binding, structural constituent of cytoskeleton | 153 ± 14 |

| CtsB (cathepsin B) | NM_007798 | Cathepsin B activity, peptidase activity, hydrolase activity | 149 ± 17 |

| Nrsn-1 (neurensin 1) | NM_009513 | Nervous system development | 141 ± 12 |

| Tubb2a (tubulin, beta2a) | NM_009450 | GTP binding, GTPase activity, structural constituent of cytoskeleton, structural molecule activity | 138 ± 10 |

| Ubl7 (ubiquitin-like 7) | NM_027086 | Protein modification process | 137 ± 15 |

| ZH10 (similar to protein C14orf111 homolog) | XM_907802 | Unknown | 135 ± 12 |

| Anapc5 (anaphase-promoting complex subunit 5) | NM_001042491 | Anaphase-promoting | 130 ± 21 |

| Sparcl1 (SPARC-like 1) | NM_010097 | Calcium ion binding | 130 ± 12 |

| LOC100045322 (Mus musculus similar to 37 kDa oncofetal antigen) | XM_001473905 | Laminin receptor precursor protein, structural constituent of ribosome | 126 ± 10 |

| Myl6 (myosin, light polypeptide 6) | NM_010860 | Calcium binding, motor activity, structural constituent of muscle | 124 ± 11 |

Among the identified cDNAs, cytohesin-2 (cyth2) most strongly increased cell migration activity of NIH3T3 fibroblast cells and HEK293 epithelial cells. Cytohesin 2 has been previously associated with cell migration. Cytohesin-2 has been reported to activate ARF6 to regulate actin reorganization and membrane ruffling.5,6 ARF6 is known to regulate cell migration5,7 and controls peripheral membrane dynamics and actin rearrangements at the plasma membrane8,9 such as stress fiber disassembly10,11 and formation of plasma membrane protrusions and ruffles.10,12,13 Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 3 (Arpc3) and neuren-sin-1 (nrsn-1) also increased migration of NIH3T3 fibroblast cells in the transwell culture inserts assays (153 ± 14% and 141 ± 12%, respectively, in comparison to the vector transfectant). Arpc3 was previously involved in podia formation14 and membrane protrusion.15 Neurensin-1 is a neuron-specific membranous protein that plays an essential role in neurite extension.16 Our selection method identified many genes that have been previously associated with cell migration and protrusion. Many cytoskeleton-related genes were also identified, therefore confirming the validity of the selection method. Some of the genes identified were subjected to network analysis using MetaCore™ software (GeneGo Inc.). Cell migration-promoting genes identified in the selection and their most relevant network neighborhood was built using “auto-expand” option in MetaCore™. The network represented cell migration-promoting genes identified in this study and their interaction partners as well as other closely associated proteins. As a result, eight genes were found in the MetaCore™ database, and they formed a cross-interaction network. In particular, Arpc3 and Myl6 were included in a canonical pathway map of cell migration and adhesion, giving further credence to the selection strategy employed. The results also suggest a feasibility of using this selection method in order to obtain a systematic view of cell migration. As the cell migration process is regulated by multiple genes through complex pathways, a large scale identification of the genes involved in cell migration is essential for the precise understanding of the cellular process.

Gain-of-function in vitro selections are powerful tools that have been used for the identification of cDNAs having phenotypes of interest.17–21 In early studies, plasmid libraries were introduced into suitable and easily transfectable selector cells followed by screening for a transiently appearing phenotype.22 Compared with the plasmid-based strategy, the retroviral vector exhibits a large cloning capacity and enables long-term expression of desired transgenes following integration into the target chromosomes. Especially, pseudotyping of transgenic retroviral particles extends their tropism and increases their transduction efficiency.23,24 Previously, retro-virus-based selections were useful tools for the identification of genes associated with specific phenotypes in vitro as well as in vivo.17–20 For instance, novel metastasis-promoting genes were recently isolated by an in vivo selection system using retroviral cDNA libraries.25

RNA interference (RNAi) screen represents loss-of-function studies. Among many biological processes that were tackled by RNAi screen, a recent report by Simpson et al.26 identified 66 genes that regulate cell migration on the basis of genome-wide RNAi screen. A high throughput wound healing screen with MCF-10A breast epithelial cells was performed using siRNAs targeting 1,081 human genes. The screen identified hits that accelerate or inhibit migration. Subsequent validation identified 66 high confidence genes that regulate cell migration with three major signaling nodes highlighted by bioinformatics analysis. Another RNAi screen that targeted tumor cell motility was done in highly motile ovarian carcinoma cell line, SKOV-3, byusing a 384-well wound-healing assay coupled with automated microscopy and wound quantification.27 The screen identified MAP4K4 as a pro-migratory kinase. A comprehensive in vivo RNAi screen for genes required for cell migration was done in C. elegance.28 The non-biased RNAi depletion experiments by light microscopy identified 99 genes required for cell migration in vivo. Genetic and physical interaction data connected 59 of these genes to form a cell migration gene network. The on-chip version of cell migration screen was also reported, where a rapid and efficient high-throughput screening procedure based on a transfection microarray was proposed.29

In summary, our in vitro selection strategy successfully identified cell migration-promoting genes. Cell migration occurs by a multistep process requiring the coordinated actions of many genes. Cell migration remains as a poorly understood process in cell biology despite extensive study. Our in vitro genetic selection method may assist in the systematic identification and characterization of additional genes that are involved in cell migration. This will advance our understanding of the cell migration process and ultimately provide new therapeutic targets for the treatment of cancer invasion/metastasis, inflammatory disease, angiogenesis and regeneration of injured tissue, where cell migration is commonly involved in the pathophysiology. Finally, combination of gain-of-function selection and loss-of-function screen may provide a comprehensive view of cell migration, which cannot be obtained by the studies focused on individual genes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (No. 2009-0078941) and Bio R&D program through the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2008-04090).

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/11073

References

- 1.Vicente-Manzanares M, Webb DJ, Horwitz AR. Cell migration at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4917–4919. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franz CM, Jones GE, Ridley AJ. Cell migration in development and disease. Dev Cell. 2002;2:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santy LC, Casanova JE. Activation of ARF6 by ARNO stimulates epithelial cell migration through downstream activation of both Rac1 and phospholipase D. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:599–610. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li CC, Chiang TC, Wu TS, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Moss J, Lee FJ. ARL4D recruits cytohesin-2/ARNO to modulate actin remodeling. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4420–4437. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palacios F, Price L, Schweitzer J, Collard JG, D’Souza-Schorey C. An essential role for ARF6-regulated membrane traffic in adherens junction turnover and epithelial cell migration. EMBO J. 2001;20:4973–4986. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donaldson JG. Multiple roles for Arf6: sorting, structuring and signaling at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41573–41576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabe H. Requirement for Arf6 in cell adhesion, migration and cancer cell invasion. J Biochem. 2003;134:485–489. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Souza-Schorey C, Boshans RL, McDonough M, Stahl PD, Van Aelst L. A role for POR1, a Rac1-interacting protein, in ARF6-mediated cytoskeletal rearrangements. EMBO J. 1997;16:5445–5454. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boshans RL, Szanto S, van Aelst L, D’Souza-Schorey C. ADP-ribosylation factor 6 regulates actin cytoskeleton remodeling in coordination with Rac1 and RhoA. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3685–3694. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3685-3694.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radhakrishna H, Klausner RD, Donaldson JG. Aluminum fluoride stimulates surface protrusions in cells overexpressing the ARF6 GTPase. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:935–947. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franco M, Peters PJ, Boretto J, van Donselaar E, Neri A, D’Souza-Schorey C, et al. EFA6, a sec7 domain-containing exchange factor for ARF6, coordinates membrane recycling and actin cytoskeleton organization. EMBO J. 1999;18:1480–1491. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mejillano MR, Kojima S, Applewhite DA, Gertler FB, Svitkina TM, Borisy GG. Lamellipodial versus filopodial mode of the actin nanomachinery: pivotal role of the filament barbed end. Cell. 2004;118:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeMali KA, Barlow CA, Burridge K. Recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to vinculin: coupling membrane protrusion to matrix adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:881–891. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki H, Tohyama K, Nagata K, Taketani S, Araki M. Regulatory expression of Neurensin-1 in the spinal motor neurons after mouse sciatic nerve injury. Neurosci Lett. 2007;421:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chilov D, Fux C, Joch H, Fussenegger M. Identification of a novel proliferation-inducing determinant using lentiviral expression cloning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:113. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiesner C, Hoeth M, Binder BR, de Martin R. A functional screening assay for the isolation of transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stitz J, Krutzik PO, Nolan GP. Screening of retroviral cDNA libraries for factors involved in protein phosphorylation in signaling cascades. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:39. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozawa T, Nishitani K, Sako Y, Umezawa Y. A high-throughput screening of genes that encode proteins transported into the endoplasmic reticulum in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:34. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komarov AP, Rokhlin OW, Yu CA, Gudkov AV. Functional genetic screening reveals the role of mitochondrial cytochrome b as a mediator of FAS-induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14453–14458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokota T, Arai N, Lee F, Rennick D, Mosmann T, Arai K. Use of a cDNA expression vector for isolation of mouse interleukin 2 cDNA clones: expression of T-cell growth-factor activity after transfection of monkey cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:68–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis PF, Emerman M. Passage through mitosis is required for oncoretroviruses but not for the human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1994;68:510–516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.510-516.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay MA, Glorioso JC, Naldini L. Viral vectors for gene therapy: the art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat Med. 2001;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/83324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gumireddy K, Sun F, Klein-Szanto AJ, Gibbins JM, Gimotty PA, Saunders AJ, et al. In vivo selection for metastasis promoting genes in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6696–6701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701145104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson KJ, Selfors LM, Bui J, Reynolds A, Leake D, Khvorova A, et al. Identification of genes that regulate epithelial cell migration using an siRNA screening approach. Nature Cell Biol. 2008;10:1027–1038. doi: 10.1038/ncb1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins CS, Hong J, Sapinoso L, Zhou Y, Liu Z, Micklash K, et al. A small interfering RNA screen for modulators of tumor cell motility identifies MAP4K4 as a promigratory kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3775–3780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cram EJ, Shang H, Schwarzbauer JE. A systematic RNA interference screen reveals a cell migration gene network in C. elegans. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4811–4818. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onuki-Nagasaki R, Nagasaki A, Hakamada K, Uyeda TQ, Fujita S, Miyake M, et al. On-chip screening method for cell migration genes based on a transfection microarray. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1502–1506. doi: 10.1039/b803879a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]