Abstract

Integrin heterodimers acquire high affinity to endothelial ligands by extensive conformational changes in both their α and β subunits. These heterodimers are maintained in an inactive state by inter-subunit constraints. Changes in the cytoplasmic interface of the integrin heterodimer (referred to as inside-out integrin activation) can only partially remove these constraints. Full integrin activation is achieved when both inter-subunit constraints and proper rearrangements of the integrin headpiece by its extracellular ligand (outside-in activation) are temporally coupled. A universal regulator of these integrin rearrangements is talin1, a key integrin-actin adaptor that regulates integrin conformation and anchors ligand-occupied integrins to the cortical cytoskeleton. The arrest of rolling leukocytes at target vascular sites depends on rapid activation of their α4 and β2 integrins at endothelial contacts by chemokines displayed on the endothelial surface. These chemotactic cytokines can signal within milliseconds through specialized Gi-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and Gi-triggered GTPases on the responding leukocytes. Some chemokine signals can alter integrin conformation by releasing constraints on integrin extension, while other chemokines activate integrins to undergo conformational activation mainly after ligand binding. Both of these modalities involve talin1 activation. In this opinion article, I propose that distinct chemokine signals induce variable strengths of associations between talin1 and different target integrins. Weak interactions of the integrin cytoplasmic tail with talin1 (the cytoplasmic integrin ligand) dissociate unless the extracellular ligand can simultaneously occupy the integrin headpiece and transmit, within milliseconds, proper allosteric changes across the integrin heterodimer back to the tail-talin1 complex. The fate of this bi-directional occupancy of integrins by both their extracellular and intracellular ligands is likely to benefit from immobilization of both ligands to cortical cytoskeletal elements. To properly anchor talin1 onto the integrin tail, a second integrin partner, Kindlin-3 may be also required, although an evidence that both partners can simultaneously bind the same integrin heterodimer is still missing. Once linked to the cortical actin cytoskeleton, the multi-occupied integrin complex can load weak forces, which deliver additional allosteric changes to the integrin headpiece resulting in further bond strengthening. Surface immobilized chemokines are superior to their soluble counterparts in driving this bi-directional occupancy process, presumably due to their ability to facilitate local co-occupancy of individual integrin heterodimers with talin1, Kindlin-3 and surface-bound extracellular ligands.

Key words: adhesion, migration, endothelium, cytoskeleton, shear stress, immunity

Firm adhesion of leukocytes to blood vessels is tightly regulated by integrins and their cognate ligands.1,2 These include the α4 integrins, VLA-4 (α4β1) and α4β7, and the β2 integrins, LFA-1 (αLβ2) and Mac-1 (αMβ2). Accumulated data suggest that these counter-receptors are structurally adapted to operate under disruptive blood-derived shear forces.3 A remarkable feature of leukocyte integrins is that their affinity state and microclustering can be regulated within fractions of seconds.4,5 The most robust signals for leukocyte integrins are transduced by chemoattractants, mostly chemokines displayed on the vessel wall.6 A growing body of evidence suggests that the Gi protein coupled receptors of these endothelial chemokines elicit diverse signaling pathways in distinct leukocyte subtypes,2,22 which use two common downstream elements to coactive all leukocyte integrins: talin1 and Kindlin-3.7 In this review, I will describe a model explaining how chemokine signals to these elements regulate the conformation of all leukocyte integrins by facilitating a coupled bi-directional occupancy and activation via both their cytoplasmic and headpiece domains.

Recent structural and biophysical studies suggest that leukocyte integrins can alternate between inactive bent conformers, which are clasped heterodimers, and variable unclasped heterodimers with extended ectodomains exhibiting intermediate and high affinity to ligand.5 Most leukocyte integrins are maintained in an inactive resting state,2 whereas in situ chemokine-stimulated integrins unfold and extend 10–25 nm above the cell surface, allowing their headpiece to readily recognize immobilized ligand on a counter surface.8 These extended integrins must undergo extensive rearrangements of their headpiece I-domains induced by external endothelial-displayed ligands in order to arrest rolling leukocytes on blood vessel walls. In leukocytes, these two canonical switches are very short-lived, implying the necessity for a stabilization. It is therefore likely that any type of robust integrin activation must involve bi-directional occupancy of the integrin by both its extracellular ligand and one or more cytoplasmic partners.9

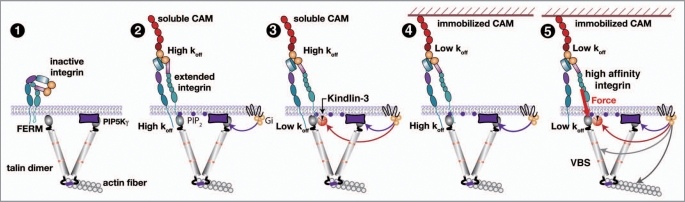

The main cytoplasmic integrin-activating adaptor in leukocytes and platelets is talin1.10,11 Talin knock down in multiple cell types results in nearly total loss of integrin activation.12,13 This actin binding adaptor binds different integrin β subunit tails with low affinity,14 which can be locally increased by in situ generated PI(4,5)P2 (PIP2). This phosphoinositide presumably binds to the FERM domain within the talin head and thereby enhances talin binding to a membrane proximal NPXY motif on the β integrin tail, a key event in integrin heterodimer unclasping.15,16 Recent studies suggest, however, that mere talin association may be insufficient to unclasp and activate the integrin heterodimer. Thus, the beta subunit tail may need to get co-occupied by the integrin co-activator, Kindlin, in order to optimize talin association with this integrin subunit.17,18 In leukocytes, Talin1 and the Kindlin family member, Kindlin 3 co-activate both VLA-4 and LFA-1 and this co-activation is dramatically enhanced by multiple chemokine triggered effectors, the nature of which has begun to unfold19 (Fig. 1). I would like to propose that talin1-Kindlin-3 co-binding to the β tails of these and other leukocyte integrins is insufficient to switch these integrins to a conformation able to bind their soluble extracellular ligands due to fast dissocia-tion of PIP2-activated talin1 from the integrin cytoplasmic tail complex. This short lived talin-integrin complex may, on the other hand, get stabilized, if the integrin headpiece can simultaneously bind an immobilized extracellular ligand and undergo immediate outside-in activation, before the talin1 has dissociated from the integrin beta tail (Fig. 1). Such full confor-mational switch can result in additional allosteric changes in the integrin-bound talin which may expose vinculin binding sites and further increase talin-actin associations that reinforce this bi-directional allosteric integrin activation.20

Figure 1.

Bi-directional integrin activation requires simultaneous co-occupancy of the integrin heterodimer by extracellular and cytoplasmic ligands. A proposed scheme for chemokine-triggered integrin activation on leukocytes. Integrin conformation is allosterically modulated in a bidirectional manner by at least two sets of ligands, extracellular and cytoplasmic. The degree of activation is dictated primarily by unclasping of the integrin heterodimer, a process dependent on the binding of the activated talin FERM domain to a specific site on the integrin β tail. (1) Inactive integrin. (2–5) Four postulated integrin conformations triggered by distinct chemokine signals. (2) Talin FERM domain activation close to the target integrin is a rate limiting step in integrin activation. This activation is triggered by PIP2 locally generated by talin-associated PIP5Kγ (purple rectangle) stimulated by a nearby Gi-coupled chemokine receptor. (3) Kindlin-3 binding to the integrin β tail stabilizes the otherwise weak talin1-integrin tail complex. The activated integrin can bind a soluble extracellular ligand with a low affinity due to a high koff of the soluble ligand from the integrin headpiece. (4) In the absence of Kindlin-3, chemokine triggered, PIP2-activated talin1 binds only transiently the integrin tail (High koff). The semiactivated integrin, even if occupied by an immobilized extracellular ligand, cannot undergo full bi-directional activation. (5) When both the extracellular ligand and talin are properly anchored, their escape from the integrin is dramatically reduced, lowering the koff. Low koff increases the probability of simultaneous bi-directional occupancy of both the integrin headpiece by the extracellular ligand and of the integrin tail by talin1 and Kindlin-3. This results in optimal bi-directional integrin activation and unclasping of the heterodimer. Stable linkages also allow this bi-directionally occupied integrin to undergo extensive mechanical strengthening by low forces applied on the headpiece; this further activates the headpiece I domains, further separates the β and α subunits from each other, and maximally stabilizes the unclasped integrin. Force application through the high affinity-talin complex can stretch the talin rod domain and expose vinculin binding sites (VBS). Since integrin ligands are generally multivalent, rapid integrin dimerization can take place to further stabilize the focal adhesion (not shown). Additional cytoplasmic partners of specific leukocyte integrins like a-actinin, L-plastin and RAPL may further strengthen subsets of focal adhesions. These and other cytosolic partners bind different integrin targets with different affinities. Therefore the effect of each of these partners on both the kinetics and stability of the talin1-integrin tail complex may vary with the cell type, the integrin type, the strength of the chemokine signal and the proximity between the integrin and its stimulatory GPCR.

How can such postulated simultaneous bi-directional occupancy of a leukocyte integrin can be so rapidly triggered by a chemokine signal encountered during leukocyte rolling on blood vessels? An attractive mechanism for in situ facilitation of talin1 binding to the integrin β tail by chemokine signals involves chemokine triggered Gi stimulated RhoA and Rac1 GTPases and their downstream target, the PIP2 generating enzyme PIP5Kγ in the vicinity of the in situ activated integrin19 (Fig. 1). Additional talin1 molecules may also be recruited to the vicinity of this initially stimulated integrin by RIAM,21 an effector that associates with activated Rap-1, one of the key chemokine stimulated GTPases involved in rapid integrin mediated activation in both leukocytes and platelets.22,23 To bidirectionally bind and activate their integrin targets, both the cytoplasmic integrin ligands, Talin1 and Kindlin-3 and the extracellular integrin ligand may need to achieve low dissociation rates from the integrin tail and headpiece, respectively. Why would an immobilized extracellular ligand be superior to soluble extracellular ligand in capacity to bi-directionally bind and activate a leukocyte integrin? The probability that a given surface-bound ligand, rather than a soluble integrin ligand would escape from its cognate integrin receptor following its dissociation is very small, since reactants in viscous medium are more likely to recombine than to diffuse apart.24 Thus, surface-immobilized single integrin ligands may rebind the integrins they recenty dissociated from much more frequently than their soluble counterparts. Similarly, the cytoplasmic ligands talin1 and Kindlin may need to remain immobile once occupying their target integrin tail. Such immobilization of talin1 can be optimized by talin anchoring to the cortical cytoskeleton.25 Talin may be also restricted from immediate dissociation from the integrin tail by Kindlin-3. An optimal integrin activating chemokine signal would therefore not only need to recruit and induce talin1 association with the β subunit of the target integrin and opening of the integrin clasp, but also need to keep the talin in an immobile state, and thereby maintain its low dissociation rate from its integrin tail sites.

As both the integrin headpiece and the integrin subunits are predicted to undergo faster opening and separation in the presence of applied forces,26,27 another tradeoff of this postulated immobilization of both the intracellular and extracellular integrin ligands is optimal force sensing of the integrin heterodimer. Application of force on the bidirectionally occupied integrin and its cognate ligands would be possible only if the integrin, its extracellular ligand, and talin1 are all properly anchored.3,28,29 Force transduction through the integrin-talin1 complex can transmit additional conformational changes on the integrin-occupied talin by exposing vinculin binding sites on the talin rod.30 Additional chemokine signals may induce talin rod phosphorylation and other changes in actin-talin associations (Fig. 1) that may further facilitate talin anchorage to the cortical cytoskeleton and subsequent microclustering of adjacent ligand-occupied integrins. It is well recognized that ligand occupancy anchors integrins to the cortical cytoskeleton.31 Thus, the anchorage states of both the extracellular and the cytoplasmic ligands of a given integrin may facilitate bidirectional integrin occupancy and optimize force driven bi-directional activation of the integrin-ligand complex and subsequent dimerization of ligand-occupied integrins. The ability of different integrin-ligand complexes to undergo diverse mechanochemical rearrangements provides a broad spectrum of integrin-ligand bond strengths, accounting for the unique capacity of chemokine stimulated leukocyte integrins to support both firm and reversible adhesions of leukocytes to their endothelial ligands.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. S. Schwarzbaum for editorial assistance, and Prof. Nir Gov and Dr. Sara W. Feigelson for fruitful discussions. I also thank Mrs. Channa Vega of the Weizmann Institute Graphics Department for assistance in scheme preparation. R. Alon is Incumbent of The Linda Jacobs Chair in Immune and Stem Cell Research. R.A. is supported by the Israel Science Foundation, the US-Israel Bi-national Science Foundation and by the FAMRI Foundation, USA.

Abbreviations

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/11133

References

- 1.Luster AD, Alon R, von Andrian UH. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1182–1190. doi: 10.1038/ni1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alon R, Dustin ML. Force as a facilitator of integrin conformational changes during leukocyte arrest on blood vessels and antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2007;26:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carman CV, Springer TA. Integrin avidity regulation: are changes in affinity and conformation underemphasized? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JJ, Butcher EC. Chemokines in tissue-specific and microenvironment-specific lymphocyte homing. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:336–341. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moser M, Bauer M, Schmid S, Ruppert R, Schmidt S, Sixt M, et al. Kindlin-3 is required for beta2 integrin-mediated leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:300–305. doi: 10.1038/nm.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shamri R, Grabovsky V, Gauguet JM, Feigelson S, Manevich E, Kolanus W, et al. Lymphocyte arrest requires instantaneous induction of an extended LFA-1 conformation mediated by endothelium-bound chemokines. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:497–506. doi: 10.1038/ni1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tadokoro S, Shattil SJ, Eto K, Tai V, Liddington RC, de Pereda JM, et al. Talin binding to integrin beta tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science. 2003;302:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1086652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Critchley DR. Biochemical and structural properties of the integrin-associated cytoskeletal protein talin. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:235–254. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrich BG, Marchese P, Ruggeri ZM, Spiess S, Weichert RA, Ye F, et al. Talin is required for integrin-mediated platelet function in hemostasis and thrombosis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3103–3111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lammermann T, Bader BL, Monkley SJ, Worbs T, Wedlich-Soldner R, Hirsch K, et al. Rapid leukocyte migration by integrin-independent flowing and squeezing. Nature. 2008;453:51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wegener KL, Basran J, Bagshaw CR, Campbell ID, Roberts GC, Critchley DR, et al. Structural basis for the interaction between the cytoplasmic domain of the hyaluronate receptor layilin and the talin F3 subdomain. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:112–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martel V, Racaud-Sultan C, Dupe S, Marie C, Paulhe F, Galmiche A, et al. Conformation, localization and integrin binding of talin depend on its interaction with phosphoinositides. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21217–2127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nayal A, Webb DJ, Horwitz AF. Talin: an emerging focal point of adhesion dynamics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larjava H, Plow EF, Wu C. Kindlins: essential regulators of integrin signalling and cell-matrix adhesion. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1203–1208. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moser M, Legate KR, Zent R, Fassler R. The tail of integrins, talin and kindlins. Science. 2009;324:895–899. doi: 10.1126/science.1163865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolomini-Vittori M, Montresor A, Giagulli C, Staunton D, Rossi B, Martinello M, et al. Regulation of conformer-specific activation of the integrin LFA-1 by a chemokine-triggered Rho signaling module. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:185–194. doi: 10.1038/ni.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz MA. Cell biology. The force is with us. Science. 2009;323:588–589. doi: 10.1126/science.1169414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han J, Lim CJ, Watanabe N, Soriani A, Ratnikov B, Calderwood DA, et al. Reconstructing and deconstructing agonist-induced activation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1796–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinashi T. Intracellular signalling controlling integrin activation in lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:546–559. doi: 10.1038/nri1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe N, Bodin L, Pandey M, Krause M, Coughlin S, Boussiotis VA, et al. Mechanisms and consequences of agonist-induced talin recruitment to platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:1211–1222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell G. Models for the specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science. 1978;200:618–627. doi: 10.1126/science.347575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Critchley DR, Gingras AR. Talin at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1345–1347. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Astrof NS, Salas A, Shimaoka M, Chen J, Springer TA. Importance of Force Linkage in Mechanochemistry of Adhesion Receptors. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15020–15028. doi: 10.1021/bi061566o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woolf E, Grigorova I, Sagiv A, Grabovsky V, Feigelson SW, Shulman Z, et al. Lymph node chemokines promote sustained T lymphocyte motility without triggering stable integrin adhesiveness in the absence of shear forces. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1076–1085. doi: 10.1038/ni1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu J, Luo BH, Xiao T, Zhang C, Nishida N, Springer TA. Structure of a complete integrin ectodomain in a physiologic resting state and activation and deactivation by applied forces. Mol Cell. 2008;32:849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puklin-Faucher E, Sheetz MP. The mechanical integrin cycle. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:179–186. doi: 10.1242/jcs.042127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.del Rio A, Perez-Jimenez R, Liu R, Roca-Cusachs P, Fernandez JM, Sheetz MP. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science. 2009;323:638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1162912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cairo CW, Mirchev R, Golan DE. Cytoskeletal regulation couples LFA-1 conformational changes to receptor lateral mobility and clustering. Immunity. 2006;25:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]