Abstract

Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) comprise a broad class of small noncoding RNAs that function as an endogenous defense system against transposable elements. Here we show that the putative DExD-box helicase MOV10-like-1 (MOV10L1) is essential for silencing retrotransposons in the mouse male germline. Mov10l1 is specifically expressed in germ cells with increasing expression from gonocytes/type A spermatogonia to pachytene spermatocytes. Primary spermatocytes of Mov10l1−/− mice show activation of LTR and LINE-1 retrotransposons, followed by cell death, causing male infertility and a complete block of spermatogenesis at early prophase of meiosis I. Despite the early expression of Mov10l1, germline stem cell maintenance appears unaffected in Mov10l1−/− mice. MOV10L1 interacts with the Piwi proteins MILI and MIWI. MOV10L1 also interacts with heat shock 70-kDa protein 2 (HSPA2), a testis-enriched chaperone expressed in pachytene spermatocytes and also essential for male fertility. These studies reveal a crucial role of MOV10L1 in male fertility and piRNA-directed retrotransposon silencing in male germ cells and suggest that MOV10L1 functions as a key component of a safeguard mechanism for the genetic information in male germ cells of mammals.

Keywords: RNA helicase, Armitage, meiosis

Approximately 45% of the human genome is derived from transposable elements, the majority of which originate from retrotransposons (1). Retrotransposons drive their own genomic replication via an RNA intermediate that is reverse transcribed before its integration into the genome. Retrotransposons can be categorized into long-terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (∼8.3% of the human genome) and non-LTR retrotransposons such as LINE-1 (long interspersed element 1; ∼16.9% of the human genome), and Alu elements (∼10.6% of the human genome) (1). LTRs are retrotransposon sequences of 300–1,000 bp that are directly repeated at the 5′ and 3′ ends. The canonical LINE-1 retrotransposon is 6 kb long and comprises a 5′ UTR with an internal RNA polymerase II promoter, two ORFs encoding for an RNA-binding protein (ORF1) and a protein with endonuclease and reverse-transcriptase activity (ORF2), and a 3′ UTR with a polyadenylation signal (2). Due to truncations and mutations, less than 100 and 3,000 of the estimated >500,000 copies of LINE-1 elements are believed to be still functional in the human and mouse genomes, respectively (3, 4). Retrotransposon replication likely has had a major impact on the evolution of the human genome (1); however, uncontrolled retrotransposon activity results in genomic instability and cell death due to insertional mutagenesis. In somatic cells, retrotransposons are suppressed by DNA methylation, but they are not suppressed in male germ cells when, during a short period of intensive epigenetic reprogramming, DNA methylation is temporarily lost (5).

Male germ cells undergo a dramatic developmental process called spermatogenesis. In mice, spermatogenesis can be divided into 12 stages, each of which consists of a specific complement of male germ cells (6). Initiated on day 3 after birth, a series of mitoses of germline stem cells, a subset of type A spermatogonia, gives rise to type B spermatogonia that appear at day 8 after birth. Leptotene, zygotene, and pachytene spermatocytes follow on days 10, 12, and 14, respectively. Meiosis of those primary spermatocytes leads to the production of haploid round spermatids that subsequently transform via elongating spermatids into mature sperm.

Recently, an endogenous Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA)-based defense system that silences retrotransposon activity in germ cells through both transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms was discovered (7). Transcriptional silencing mechanisms include piRNA-mediated DNA remethylation of retrotransposon regions (5). piRNAs are a multitudinous class of ∼26- to 31-nucleotide RNA molecules that are processed by a Dicer-independent mechanism from long, single-stranded precursor transcripts that often encode several piRNAs (7). Germ cells in mice express two types of piRNAs: (i) a small fraction of piRNAs derived from repetitive genomic regions expressed during mouse embryogenesis and (ii) a larger fraction of piRNAs derived from nonrepetitive regions that starts to become expressed during the pachytene stage of meiosis (pachytene piRNAs) (7). Pachytene piRNAs interact with MIWI (mouse PIWI) and MILI (MIWI-like), two of the three murine Piwi proteins, a subfamily of the Argonaute-proteins (8). MIWI2, the third murine Piwi protein, is also expressed specifically in the germline before birth.

We discovered a putative DExD-box helicase (called CHAMP; cardiac helicase activated by MEF2C protein), encoded by differently sized transcripts in heart (exons 15–26) and testis (exons 1–26) (9). The testis-specific isoform has also been referred to as MOV10-like-1 (MOV10L1), on the basis of its extensive homology to Moloney leukemia virus 10 (MOV10), which was shown to interact with argonaute 1 and 2 in HeLa cells (10). The Drosophila homolog of CHAMP/MOV10L1/MOV10, known as Armitage, is necessary for piRNA processing in germ cells of Drosophila (11, 12).

To investigate the function of MOV10L1 in mammals, we generated mice harboring a global deletion of the Mov10l1 gene. These mice were viable and healthy, but male Mov10l1-null (Mov10l1−/−) mice were infertile due to apoptotic loss of early pachytene spermatocytes, which was preceded by retrotransposon activation. Our results identify MOV10L1 as an interacting partner of MILI and MIWI, and we conclude that this interaction is a key conserved feature in safeguarding DNA of male germ cells against retrotransposons.

Results and Discussion

Mov10l1 Is Predominantly Expressed in Pachytene Spermatocytes.

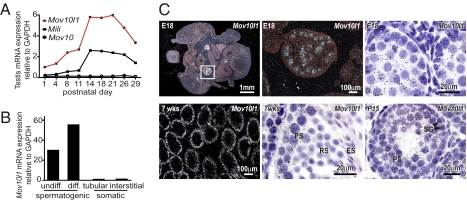

Recent studies show that the function of PIWI in germ cells of Drosophila depends on the putative RNA helicase Armitage (11, 12). Mice and humans have two genes that are predicted to be homologous to Armitage, Mov10, and Mov10l1. To determine the expression patterns of these putative Armitage homologs in mouse testis, we analyzed expression of Mov10 and Mov10l1 postnatally during development of the first spermatogenic waves (Fig. 1A). On the basis of microarray data that we had previously deposited at the Gene Omnibus database, expression of Mov10 was low and did not change significantly between postnatal days (P) 1 and 29. In contrast, by P14, the relative abundance of Mov10l1 had increased sixfold to peak with the rise of pachytene spermatocytes. After P21, the abundance of Mov10l1 transcripts steadily declined, coincident with the emergence of the first generations of round and elongating spermatids. This expression pattern mirrored that of Mili, one of the three murine Piwi genes that are necessary for piRNA synthesis and function. To determine whether Mov10l1 expression in testis was restricted to spermatogonic cells, we analyzed spermatogonic and somatic cell fractions from mouse testis. Mov10l1 transcripts were abundant in spermatogenic cells, but absent in tubular or interstitial somatic cells (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Mov10l1 is specifically expressed in spermatocytes within the testis. (A) Expression of Mov10l1, Mov10, and Mili mRNA in testes of C57BL/6 mice during postnatal development (GEO Series GES640). (B) Mov10l1 mRNA expression in fractions of undifferentiated (undiff.) spermatogonia and spermatocytes (diff.) compared with tubular and interstitial somatic testis cells isolated from testes of 19-d-old C57BL/6 mice (GEO series GES829). (C) Detection of Mov10l1 in embryonic (Upper) and juvenile/adult (Lower) testes by radioactive in situ hybridization with a probe directed against the C-terminal region of Mov10l1; exposure was 3 wk for embryonic and 1 week for postnatal tissue. (Upper Left) A dark-field image of a transverse section through the lower abdomen of an embryonic day 18 (E18) mouse. (Upper Center) An enlargement of Upper Left showing Mov10l1 mRNA as bright white dots in testis. (Upper Right) A high-magnification bright-field image of a seminiferous tubule depicting Mov10l1 as black silver grains localized specifically in gonocytes. (Lower) Detection of Mov10l1 in 7-wk-old adult (Lower Left, dark-field; Lower Center, bright-field) and in P15 juvenile (Lower Right) mouse testis. PS, pachytene spermatocytes; RS, round spermatids; ES, elongating spermatids; SG, spermatogonia.

To verify that Mov10l1 expression is restricted to the germline, we performed radioactive in situ hybridization on testis sections at embryonic day 18 (E18), at P15, and at 7 wk of age. Two separate probes directed against the sense strand of the C-terminal coding region of Mov10l1 and the 3′ UTR of Mov10l1, respectively, showed an identical expression pattern of Mov10l1. At E18, Mov10l1 was specifically expressed within the testis in gonocytes, not in tubular or interstitial somatic cells (Fig. 1C, Upper). In juvenile (P15) and adult mice (7 wk old), Mov10l1 expression was most abundant in pachytene spermatocytes and absent in more mature spermatogenic cells and in somatic cells (Fig. 1C, Lower). Notably, exposure of the embryonic tissue was 3 wk, whereas exposure of juvenile and adult testis sections was only 1 wk, resulting in an overestimation of the expression of Mov10l1 in embryonic compared with adult testis. A negative control probe directed against the antisense strand of the C-terminal coding region of Mov10l1 showed no specific signal.

In addition to full-length Mov10l1, two additional Mov10l1 transcripts, Champ and Csm (cardiac specific transcript of Mov10l1), were described previously as smaller transcripts (9, 13, 14) (Fig. S1A). EST databases also suggested an additional transcript starting at exon 20 (E20-SV). We determined expression of all four putative Mov10l1 transcripts in heart and testis by real-time PCR (Fig. S1B). We found that, in addition to the very weak expression of the putative exon 20 transcript, adult testis expressed only full-length Mov10l1 and adult heart predominantly the Csm transcript, suggesting that the Mov10l1 signal, which was detected by microarray and in situ hybridization analysis of testis tissue, represents full-length Mov10l1.

Global Deletion of Mov10l1 Blocks Spermatogenesis During Meiosis I.

To assess the function of Mov10l1 in vivo, we generated mice lacking a functional Mov10l1 gene. Because it has been shown that the helicase domain residing in exon 20 is necessary for an antiproliferative function of CHAMP in vitro (15), and because both CHAMP and MOV10L1 share this domain, we chose to flank exon 20 of the Mov10l1 gene with loxP sites (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2A). We generated targeted embryonic stem cells that carried the floxed exon 20 of Mov10l1 as shown by Southern blot analysis (Fig. S2B) and injected those mutant cells into blastocysts to obtain chimeric mice. For generation of Mov10l1 knockout mice, we crossed germline-transmitted mice to transgenic mice that globally expressed Cre recombinase under the control of the CAG promoter (CAG-Cre). The absence of Mov10l1 mRNA starting from exon 20 was confirmed by PCR (Fig. S2C). Furthermore, we did not observe any specific Mov10l1 signal in testis sections of Mov10l1−/− mice by radioactive in situ hybridization (Fig. S2D). Deletion of Mov10l1 did not result in compensatory expression of Mov10 (Fig. S2E).

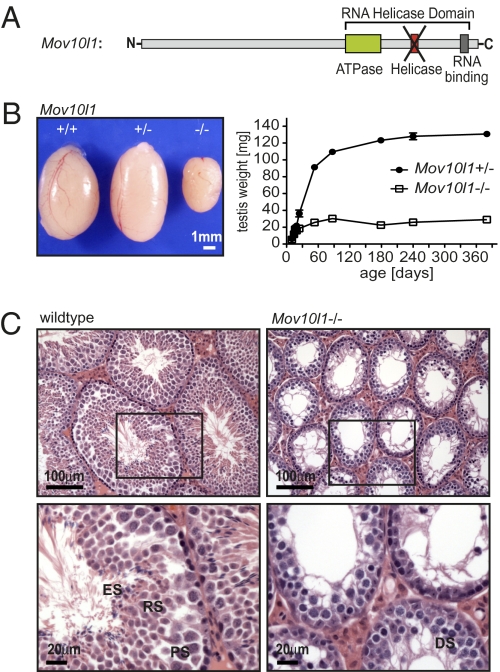

Fig. 2.

Mov10l1−/− mice have a reduced testis size secondary to a lack of spermatids. (A) Scheme of the predicted MOV10L1 domains. For generation of Mov10l1−/− mice, the exon encoding the putative helicase domain (red) was flanked by LoxP sites, and global deletion of Mov10l1 was then achieved by breeding Mov10l1+/fl mice to CAG-Cre transgenic mice. (B) Mov10l1−/− mice showed reduced testis size compared with Mov10l1+/− and Mov10l1+/+ mice. (Left) Testes of 3-mo-old mice from the same litter. (Right) Testis weight of Mov10l1+/− and Mov10l1−/− mice. Each time point represents the mean of two to six testes. (C) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of transverse sections through testes of 3-mo-old wild-type versus Mov10l1−/− mice. (Lower) An enlargement of the regions indicated by the black frame in the Upper. ES, elongating spermatids; RS, round spermatids; PS, pachytene spermatocytes; DS, degenerating spermatocytes with condensed nuclei.

Mov10l1−/− mice were obtained at predicted Mendelian ratios from heterozygous intercrosses. Mov10l1−/− mice appeared healthy, even though they also lacked expression of CHAMP and CSM in the heart; however, male Mov10l1−/− mice were infertile.

It was recently suggested that reduced Mov10l1 levels were at least partially responsible for accelerated ovarian aging and follicle depletion in mice that lack the transcriptional regulator TAF4B (16). However, in contrast to this proposal, female Mov10l1−/− mice appeared to have normal and sustained fertility (9 ± 1.1 pups per litter; n = 10 litters), and we assume therefore that reduced Mov10l1 expression in TAF4B−/− mice is a marker rather than a cause for accelerated ovarian aging. The lack of an obvious phenotype of Mov10l1−/− mice in ovaries is surprising given the fact that ovaries also express piRNAs. However, other mouse models with genetic deletions of proteins involved in piRNA processing/function also show solely male infertility (17–21).

Testes of 3-mo-old Mov10l1−/− mice were significantly smaller than testes of Mov10l1+/− or Mov10l1+/+ littermates (Fig. 2B). This phenotype was observed with 100% penetrance, emphasizing the crucial importance of Mov10l1 even in a mixed genetic background. We determined testis weight at different ages and found that developmental increase in testis size was initially normal in Mov10l1−/− mice; however, growth was markedly slowed at postnatal week 3 and arrested shortly thereafter (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2F). The overall testis architecture seemed to be normal; however, individual seminiferous tubules of Mov10l1−/− testes were significantly smaller than those of wild-type testes, explaining the reduced size of testes in Mov10l1−/− mice (Fig. 2C). Seminiferous tubules of testes from adult Mov10l1−/− mice contained Sertoli cells and early stages of spermatogonic cells; however, many pachytene-like spermatocytes appeared to have degenerating nuclei and round, and elongating spermatids were missing completely (Fig. 2C, Lower). Furthermore, epididymides of adult Mov10l1−/− mice were free of any mature sperm (Fig. 3 A and B).

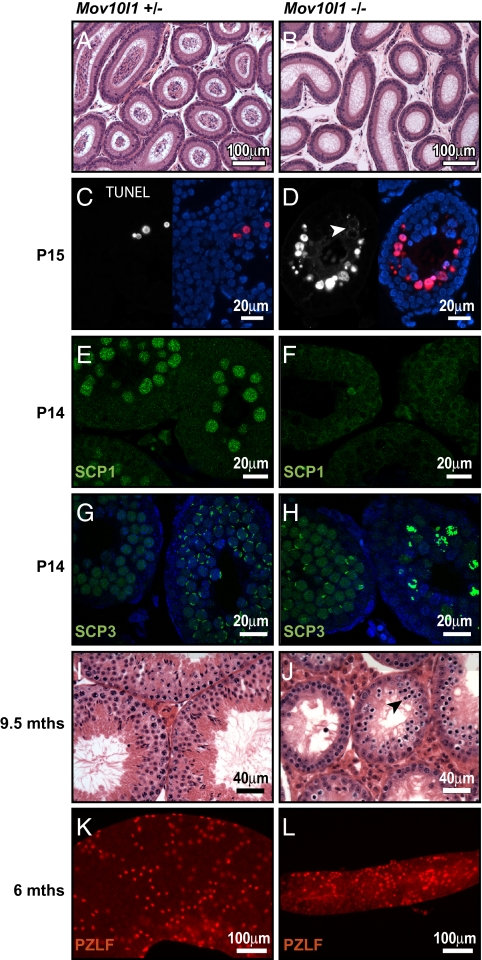

Fig. 3.

Infertility of Mov10l1−/− mice due to cell death of early pachytene spermatocytes. (A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of epidydimides of 3-mo-old mice. Sperm were absent in epidydimides of Mov10l1−/− mice. (C and D) TUNEL staining of sections from testis of P15 Mov10l1+/− and Mov10l1−/− mice, respectively. (Left) Red channel with the apoptotic nuclei. (Right) Overlay with DAPI-stained nuclei (blue). (E–H) Confocal microscopy images of immunofluorescent staining of testis sections from P14-old mice for SCP1 (synaptonemal complex protein 1) and SCP3, respectively; counterstaining of nuclei with DAPI (blue) in G and H. (I and J) H&E staining of transverse sections of 9.5-mo-old mice; seminiferous tubules Mov10l1−/− mice still contained many spermatocytes and degenerating cells (arrowhead in J). (K and L) PZLF staining of tubules isolated from testes of 6-mo-old wild-type and Mov10l1−/− mice, respectively.

To determine the time of onset of abnormalities in Mov10l1−/− testis, we examined testis sections during development of the first generations of type B spermatogonia (P8), leptotene spermatocytes (P10), and pachytene spermatocytes (P14 and P15) (Fig. S3 A–H). Cross-sections of Mov10l1−/− and Mov10l1+/− testes appeared similar until P14. However, beginning at P15, seminiferous tubules of Mov10−/− mice demonstrated degenerating cells with hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. S3 G and H). TUNEL staining of the same sections to determine abundance of apoptotic cells showed similar numbers of apoptotic cells in Mov10l1+/− and Mov10l1−/− mice at P8, P10, and P14. Starting at P15, some seminiferous tubules of Mov10l1−/− mice showed massive TUNEL staining of the most mature spermatocytes (Fig. 3 C and D). Interestingly, in contrast to the specific staining of nuclei in apoptotic cells of control animals, TUNEL staining in strongly affected tubules of Mov10l1−/− mice seemed to start in the cytoplasm (arrowhead in Fig. 3D) and was seen later in nuclei. At 5 wk of age, the majority of seminiferous tubules in Mov10l1−/− mice showed an abundance of TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. S3 K–N).

To further define the meiotic defects in Mov10l1−/− testes, we analyzed the assembly of the synaptonemal complex (SC) by immunostaining. Expression of SCP (synaptonemal complex protein) 1, which is a major component of the transverse filaments of the SC and is first expressed in zygotene spermatocytes, was absent in Mov10l1−/− testes (Fig. 3 E and F). Expression of SCP3, which is a component of the axial element of the SC and is expressed from leptotene spermatocytes to late meiotic cells, appeared in some seminiferous tubules of Mov10l1−/− mice similarly to the tubules of wild-type mice (Fig. 3 G and H). However, in contrast to wild-type mice, the majority of seminiferous tubules of Mov10l1−/− mice showed relatively strong, abnormal staining of chromosomal structures (Fig. 3H, right tubule), which might indicate failure of the SC to assemble properly in more differentiated germ cells. Thus, disruption of Mov10l1 causes meiotic blockade before the pachytene stage.

Because Mov10l1 mRNA is already expressed in gonocytes (Fig. 1C, Upper) and because deletion of several PIWI-complex proteins such as MILI, MIWI2, and GASZ causes Sertoli-cell-only tubules due to a progressive loss of undifferentiated germ cells with age (19, 20, 22), we also performed histological analysis of testes from 9.5-mo-old Mov10l1−/− mice. Seminiferous tubules of these old Mov10l1−/− mice still showed a high cell turnover with many mitotic and degenerating cells, suggesting that MOV10L1 is not required for maintenance of germline stem cells (Fig. 3 I and J). Furthermore, staining of PLZF (promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger), a marker for undifferentiated germ cells (23), in tubules of 6-mo-old mice, showed that, even though isolated tubules of Mov10l1−/− mice were significantly thinner than wild-type tubules, they nevertheless contained numerous undifferentiated spermatogonia (Fig. 3 K and L).

Mov10l1 Is Necessary for piRNA-Dependent Repression of Retrotransposons.

Massive cell death, which resulted in the lack of round and elongating spermatocytes in Mov10l1−/− mice, started at P15. To investigate the mechanism for cell death in Mov10l1−/− mice, we compared the gene expression patterns of testes from Mov10l1+/− and Mov10l1−/−mice at 10, 12, and 14 d of age. Genes up-regulated more than twofold or down-regulated >50% at P14 in Mov10l1−/− mice compared with Mov10l1+/− mice are presented in Dataset S1 and Dataset S2. At P12, gene expression was similar in Mov10l1+/− and Mov10l1−/− mice. However, many genes that were up-regulated between P12 and P14 in Mov10l1+/− mice failed to be up-regulated in Mov10l1−/− mice. These findings suggest that Mov10l1−/− mice have a block of spermatogenesis starting at the transition from zygotene to pachytene spermatocytes. Surprisingly, there was also a subset of transcripts that was specifically up-regulated in Mov10l1−/− mice at P14. Among those, the most prominent up-regulated transcripts represented retrotransposons from the LINE and LTR family, and up-regulation of some of those retrotransposons started as early as P10 (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

MOV10L1 interacts with Piwi proteins and is necessary for piRNA-dependent repression of retrotransposons. (A and B) Up-regulation of retrotransposons in Mov10l1−/− mice. (A) Microarray analysis of pooled total RNA (n = 3) from testes of Mov10l1−/− mice versus Mov10l1+/− mice at postnatal days 10, 12, and 14. The depicted retrotransposon families from the LINE and LTR class were among the strongest up-regulated transcripts in Mov10l1−/− mice at P14. (B) Immunofluorescent staining of testis sections from P14 mice for the LINE ORF1 protein (ORF1p, green); counterstaining of nuclei with DAPI (blue). (C) Total RNA of testis from 24-d-old Mov10l1+/− mice versus Mov10l1−/− mice was end-labeled with [32P]ATP and detected after denaturing PAGE. In Mov10l1−/− mice, ∼29-nucleotide-long RNAs, most likely representing piRNAs, were strongly reduced. (D) Total RNA from testis of P14 and P24 Mov10l1+/− versus Mov10l1−/− mice was isolated and used for Northern blotting to detect specific piRNAs (piR-4868 and piR-1) and miRNAs (let-7a). An ethidum bromide-stained polyacrylamide gel is shown as a loading control. (E) Detection of the Piwi proteins Mili and Miwi (white) in testis sections from P14 Mov10l1+/− versus Mov10l1−/− mice by immunofluorescent staining. (F) COS1 cells were cotransfected with expression plasmids for Flag-tagged MOV10L1 and Myc-tagged MILI and MIWI, respectively. Lysates were then used for coimmunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibodies followed by Western blot analysis with anti-Myc antibodies. Input lanes represent 1% of lysates used for coimmunoprecipitation. The experiment was repeated three times; representative immunoblots are shown. Reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation worked similarly.

We looked by immunostaining for expression of ORF 1 protein (ORF1p), one of the two proteins expressed by functional LINE retrotransposons, in testis sections of 14-d-old Mov10l1−/− mice. Although there was nearly no ORF1p detectable in Mov10l1+/− mice, more mature spermatocytes of nearly all seminiferous tubules of Mov10l1−/− mice showed strong cytoplasmic and nuclear ORF1p expression (Fig. 4B).

Because it is known that piRNAs repress retrotransposon expression in testis, we determined small RNA expression in testes of Mov10l1−/− mice by radioactive SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4C). Remarkably, expression of ∼29-nucleotide RNAs, most likely representing piRNAs, was abolished in Mov10l1−/− mice. Also, individual piRNAs that were detected by Northern blot analysis were absent in Mov10l1−/− mice (Fig. 4D, Top), which might be at least partially due to the loss of the piRNA-rich pachytene spermatocytes and later germ cells in Mov10l1−/− mice. MOV10, the close homolog of MOV10L1, was recently identified as an interaction partner of Argonaute 1 and 2 in HeLa cells and suggested to be involved in microRNA processing (10). However, in Mov10l1−/− mice, expression of microRNAs (e.g., let-7a) seemed to be unaffected (Fig. 4D, Bottom). This is not surprising, given that complete removal of microRNAs in germ cells by testis-specific deletion of Dicer 1 caused a severe reduction in the number of elongating spermatids and motile mature sperm (24), in contrast to deletion of Mov10l1.

MOV10L1 Interacts with the Piwi Proteins MIWI and MILI.

Proper piRNA processing and function require a multiprotein complex that contains as core components members of the Piwi protein family. Piwi proteins represent a subfamily of Argonaute proteins containing a Piwi and a PAZ domain. Three PIWI protein homologs have been identified in the mouse genome: MIWI, MIWI2, and MILI. Genetic deletion of each Piwi protein results in male infertility; deletions of Miwi2 and Mili block spermatogenesis at early prophase of meiosis I, and deletion of Miwi blocks postmeiotically in round spermatids (17–19). Mov10l1 and Mili display similar expression patterns, and deletion of Mov10l1 in mice seems to phenocopy most closely the deletion of Mili.

We therefore analyzed expression of Piwi proteins in Mov10l1−/− mice. Miwi and Mili mRNA expression was strongly induced in Mov10l1+/− mice at P14, but was abrogated in Mov10l1−/− mice (Fig. S4), possibly due to an arrest of spermatocyte differentiation before the onset of Miwi/Mili expression. To determine protein expression of MILI and MIWI, we performed immunofluorescent staining with specific antibodies on testis sections of 14-d-old mice. Protein expression of MIWI and MILI was undetectable in Mov10l1−/− mice (Fig. 4E).

To investigate a possible direct interaction of MILI and MIWI with MOV10L1, we assayed whether MOV10L1 could coimmunoprecipitate with MILI or MIWI in COS cells. Indeed, both MILI and MIWI could directly bind to MOV10L1 (Fig. 4F).

Loss of MILI protein in spermatocytes of Mov10l1−/− mice could explain the phenotype seen in Mov10l1−/− mice. However, in contrast to the deletion of MOV10L1, deletion of MILI and other Piwi complex proteins such as MIWI2, GASZ, or Maelstrom results in a progressive loss of undifferentiated germ cells with age (19, 20, 22, 25). Nevertheless, because Mov10l1 is already expressed at low levels in gonocytes, we cannot exclude the possibility that gonocytes of Mov10l1−/− mice exhibit an altered methylation status of retrotransposon regions as seen in mice with deletion of Miwi2, which also have a block of spermatogenesis during meiosis even though Miwi2 is expressed only before birth (19).

HSPA2 Is an Interaction Partner of Mov10l1.

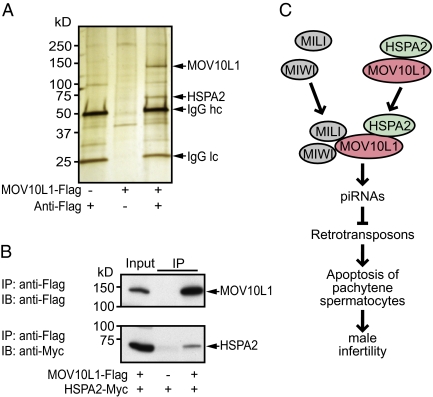

To identify other interaction partners of MOV10L1, we bound Flag-tagged MOV10L1 to IgG-Flag-Sepharose, incubated it with testis lysates from 20-d-old wild-type mice, and separated the coimmunoprecipitate by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining (Fig. 5A). In addition to the MOV10L1 band, which migrated near its predicted molecular weight of 133 kDa, we identified a protein of ∼70 kDa that was absent in the control lanes. Mass spectrometric (MS) analysis revealed that the 70-kDa band was heat shock 70-kDa protein 2 (HSPA2) (Fig. S5A). By performing a BLAST search with the individual peptide fragments that were identified in the 70-kDa band by MS, we verified that HSPA2 originated from the mouse-testis lysate, not from the monkey-derived COS cells, in which we had generated the recombinant MOV10L1 protein (Fig. S5B). Interestingly, onset of Hspa2 expression in pachytene spermatocytes coincides with the time when Mov10l1 expression increases (Fig. S5C). Furthermore, genetic deletion of Hspa2 in mice caused a phenotype remarkably similar to that of Mov10ll−/− mice (26). However, the mechanistic basis for the spermatogenic arrest in Hspa2−/− mice has been unclear. To confirm a direct interaction of HSPA2 with MOV10L1, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays in COS cells and found that HSPA2 indeed binds directly to MOV10L1 (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

HSPA2 is an interaction partner of MOV10L1. (A) Identification of MOV10L1-interacting partners by pull-down experiment with recombinant MOV10L1. Forty-eight hours before harvesting, COS cells were Mock-transfected (left lane) or transfected with a plasmid expressing Flag-tagged MOV10L1 (center and right lanes). Lysates were then incubated with anti-Flag antibody and Sepharose A (left and right lanes) or only with Sepharose A (center lane). Flag-tagged MOV10L1 bound to the Sepharose was then incubated with lysates from P20 mouse testis. Proteins bound to MOV10L1 and Sepharose were separated by SDS-PAGE. After silver staining of the gel, protein bands that were visible only in the right lane, but not in the two control lanes, were cut out and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. HSPA2, heat shock 70-kDa protein 2; IgG, Ig; hc, heavy chain; lc, light chain. (B) COS1 cells were cotransfected with expression plasmids for Flag-tagged MOV10L1 and Myc-tagged HSPA2. Lysates were then used for coimmunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibodies followed by Western blot analysis with anti-Myc antibodies. Input lanes represent 1% of lysates used for coimmunoprecipitation. Reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation worked similarily. (C) Model for the role of MOV10L1 during spermatogenesis. MOV10L1 interacts with MILI and MIWI, which is necessary for piRNA-induced repression of retrotransposons in pachytene spermatocytes. MOV10L1 interacts further with HSPA2.

HSPA2 belongs to the family of heat-shock proteins (HSPs), which are typically expressed upon sublethal heat shocks and other stresses. HSPA2, however, is constitutively expressed in brain and at higher levels in testis, where its expression starts with leptotene/zygotene spermatocytes (27). Low levels of Hspa2 expression in humans were associated with low sperm count (oligozoospermia), suggesting that HSPA2 is necessary for sperm maturation or germ cell survival (28). HSPs often function as chaperones that stabilize the structure and facilitate the folding of other proteins. Our data, showing physical interaction between MOV10L1 and HSPA2, coupled with the similar phenotypes resulting from deletion of either gene, suggest that HSPA2 might be involved in MOV10L1 function, possibly by stabilizing MOV10L1.

Potential Clinical Relevance of MOV10L1.

The fact that MOV10L1 does not seem to be necessary for germline stem-cell renewal suggests that the block of spermatogenesis in Mov10l1−/− mice might be reversible by reintroducing Mov10l1 into germline stem cells. This might be clinically relevant if loss-of-function mutations in the Mov10l1 gene are a cause for male infertility in humans. Furthermore, temporarily decreasing MOV10L1 expression (e.g., by siRNA or small molecules) or inhibiting MOV10L1 activity might be a reversible means for male birth control. This approach might also be relatively safe because full-length MOV10L1 seems to be expressed in males only in germ cells and loss of MOV10L1 in mice affected only spermatogenesis.

Finally, we note that Mov10l1, in addition to being expressed in the testis, is also expressed as a cardiac-specific isoform in the heart (9, 13). We have thus far observed no cardiac abnormalities in Mov10l1−/− mice. It will be interesting, however, to determine whether MOV10L1 plays a role in the heart under conditions of stress.

Materials and Methods

In Situ Hybridization.

In situ hybridization was performed on paraformaldehyde (PFA)-fixed sections with probes directed against the 3′ UTR and, respectively, the C-terminal region of Mov10l1. 35S-UTP–labeled sense and antisense RNA probes were generated by in vitro transcription with SP6 and T7 polymerase (Maxiscript, Ambion), respectively.

Immunohistological Examination.

For immunofluorescence staining, PFA-fixed sections were deparaffinized and then boiled for 10 min in citrate solution (BioGenex) for antigen retrieval. After 30 min blocking with 2% goat serum, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody. Anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated with Alexa 488 (1:500; Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

COS cells were transfected with pCMV6 expression vectors for N-terminal Flag-tagged MOV10L1 and N-terminal Myc-tagged MIWI, MILI, and HSPA2, respectively. After 48 h, COS cells were lysed in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (complete mini; Roche). After syringe-and-needle homogenization, the cell lysate was centrifuged 10 min at 15,000 × g. The supernatant was then preincubated for 2 h with Protein A/G Sepharose (Ultralink, Pierce). Immunoprecipitation was carried out with mouse anti-FLAG M2 antibody (#F1804, Sigma). Immunoprecipitates were then separated by 10% gradient SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad) and analyzed by Western blotting using mouse anti-Myc antibody (1:2,000, #sc-40, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Generation of Conditional Mov10l1 Knockout Mice.

For generation of the Mov10l1 targeting vector, the pGKNEO-F2L2DTA plasmid (Addgene plasmid 13445) was used. All experimental animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Experiments are described in more detail in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Barry Shur and Martin Matzuk for insightful comments, Jose Cabrera for help with graphics, John Shelton for help with in situ hybridization, Mike Haberland for advice on generating Mov10l1−/− mice, Heng-Chi Lee for advice on small RNA detection, Aaron Johnson for help with confocal microscopy, Andrew Williams for critical reading of the manuscript, Sandra L. Martin (University of Colorado, School of Medicine) for LINE ORF1p antibody, Heather Powell for help with PZLF staining, and Robert Hammer, Ildi Bock-Marquette, Zhi-Ping Liu, and the members of the Olson laboratory for many helpful discussions. Injection of ES cells for generation of Mov10l1−/− mice was performed by the Transgenic Core Facility and mass spectrometric analysis by the Protein Chemistry Technology Center of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Work in the laboratory of E.N.O. was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Foundation Leducq TransAtlantic Network of Excellence Program, and the Robert A. Welch Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1007158107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cordaux R, Batzer MA. The impact of retrotransposons on human genome evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:691–703. doi: 10.1038/nrg2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babushok DV, Kazazian HH., Jr Progress in understanding the biology of the human mutagen LINE-1. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:527–539. doi: 10.1002/humu.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouha B, et al. Hot L1s account for the bulk of retrotransposition in the human population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5280–5285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831042100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazazian HH., Jr Mobile elements: Drivers of genome evolution. Science. 2004;303:1626–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1089670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aravin AA, Bourc'his D. Small RNA guides for de novo DNA methylation in mammalian germ cells. Genes Dev. 2008;22:970–975. doi: 10.1101/gad.1669408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed EA, de Rooij DG. Staging of mouse seminiferous tubule cross-sections. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;558:263–277. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-103-5_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aravin AA, Hannon GJ. Small RNA silencing pathways in germ and stem cells. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:283–290. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girard A, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Carmell MA. A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins. Nature. 2006;442:199–202. doi: 10.1038/nature04917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu ZP, et al. CHAMP, a novel cardiac-specific helicase regulated by MEF2C. Dev Biol. 2001;234:497–509. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meister G, et al. Identification of novel argonaute-associated proteins. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2149–2155. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malone CD, et al. Specialized piRNA pathways act in germline and somatic tissues of the Drosophila ovary. Cell. 2009;137:522–535. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vagin VV, et al. A distinct small RNA pathway silences selfish genetic elements in the germline. Science. 2006;313:320–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1129333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueyama T, Kasahara H, Ishiwata T, Yamasaki N, Izumo S. Csm, a cardiac-specific isoform of the RNA helicase Mov10l1, is regulated by Nkx2.5 in embryonic heart. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28750–28757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang PJ, McCarrey JR, Yang F, Page DC. An abundance of X-linked genes expressed in spermatogonia. Nat Genet. 2001;27:422–426. doi: 10.1038/86927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu ZP, Olson EN. Suppression of proliferation and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by CHAMP, a cardiac-specific RNA helicase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2043–2048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261708699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovasco LA, et al. Accelerated ovarian aging in the absence of the transcription regulator TAF4B in mice. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:23–34. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.077495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng W, Lin H. miwi, a murine homolog of piwi, encodes a cytoplasmic protein essential for spermatogenesis. Dev Cell. 2002;2:819–830. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, et al. Mili, a mammalian member of piwi family gene, is essential for spermatogenesis. Development. 2004;131:839–849. doi: 10.1242/dev.00973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carmell MA, et al. MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Dev Cell. 2007;12:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma L, et al. GASZ is essential for male meiosis and suppression of retrotransposon expression in the male germline. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoji M, et al. The TDRD9-MIWI2 complex is essential for piRNA-mediated retrotransposon silencing in the mouse male germline. Dev Cell. 2009;17:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unhavaithaya Y, et al. MILI, a PIWI-interacting RNA-binding protein, is required for germ line stem cell self-renewal and appears to positively regulate translation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6507–6519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809104200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buaas FW, et al. Plzf is required in adult male germ cells for stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet. 2004;36:647–652. doi: 10.1038/ng1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maatouk DM, Loveland KL, McManus MT, Moore K, Harfe BD. Dicer1 is required for differentiation of the mouse male germline. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:696–703. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.067827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soper SF, et al. Mouse maelstrom, a component of nuage, is essential for spermatogenesis and transposon repression in meiosis. Dev Cell. 2008;15:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dix DJ, et al. Targeted gene disruption of Hsp70-2 results in failed meiosis, germ cell apoptosis, and male infertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3264–3268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inselman AL, et al. Heat shock protein 2 promoter drives cre expression in spermatocytes of transgenic mice. Genesis. 2010;48:114–120. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cedenho AP, et al. Oligozoospermia and heat-shock protein expression in ejaculated spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1791–1794. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.