Abstract

During infection, vertebrates develop “sickness syndrome,” characterized by fever, anorexia, behavioral withdrawal, acute-phase protein responses, and inflammation. These pathophysiological responses are mediated by cytokines, including TNF and IL-1, released during the innate immune response to invasion. Even in the absence of infection, qualitatively similar physiological syndromes occur following sterile injury, ischemia reperfusion, crush injury, and autoimmune-mediated tissue damage. Recent advances implicate high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a nuclear protein with inflammatory cytokine activities, in stimulating cytokine release. HMGB1 is passively released during cell injury and necrosis, or actively secreted during immune cell activation, positioning it at the intersection of sterile and infection-associated inflammation. To date, eight candidate receptors have been implicated in mediating the biological responses to HMGB1, but the mechanism of HMGB1-dependent cytokine release is unknown. Here we show that Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a pivotal receptor for activation of innate immunity and cytokine release, is required for HMGB1-dependent activation of macrophage TNF release. Surface plasmon resonance studies indicate that HMGB1 binds specifically to TLR4, and that this binding requires a cysteine in position 106. A wholly synthetic 20-mer peptide containing cysteine 106 from within the cytokine-stimulating B box mediates TLR4-dependent activation of macrophage TNF release. Inhibition of TLR4 binding with neutralizing anti-HMGB1 mAb or by mutating cysteine 106 prevents HMGB1 activation of cytokine release. These results have implications for rationale, design, and development of experimental therapeutics for use in sterile and infectious inflammation.

Keywords: innate immunity, infection, sterile inflammation, TNF, proximity ligation assay

A major unanswered question in clinical medicine is why sterile injury occurring after shock, ischemia-reperfusion, or crush injury leads to clinical sickness responses that are qualitatively indistinguishable to those occurring after infection. Cytokines released during the innate immune response to injury are necessary and sufficient to mediate many, if not all of these sickness responses, including fever, anorexia, fatigue, acute-phase responses, inflammation, and lethal tissue injury in lungs, heart, kidneys, and other organs. High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a ubiquitous DNA-binding protein secreted by immunocompetent cells, including monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells, is a necessary and sufficient mediator of severe sepsis, the syndrome of lethal inflammation that occurs following infection (1–4). Immune cells activated by exposure to the products of pathogenic bacteria and viruses actively mobilize HMGB1, and translocate it from the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where it is packaged into secretory vesicles and released into the extracellular milieu (5). Other cells have been implicated as significant sources of secreted HMGB1, including platelets, endothelial and epithelial cells, fibroblasts, muscle cells, neurons, and microglial cells (4). Administration of neutralizing antibodies and other selective HMGB1 antagonists prevent and reverse organ damage and lethality during severe sepsis in established preclinical disease models (6, 7).

Importantly, however, a large body of evidence indicates that HMGB1 is also required for the development or progression of inflammation, even in the absence of infection, as occurs during experimental autoimmune arthritis, cerebral ischemia, hemorrhagic shock, pancreatitis, sterile hepatic necrosis, and other conditions that lead to inflammation and tissue injury (5). HMGB1 release in these cases does not necessarily require exposure of immune cells to exogenous pathogenic products, because HMGB1 can be released by somatic cells that are undergoing necrosis. Billiar and colleagues discovered that HMGB1 is released during sterile ischemia-reperfusion injury and is a proximal trigger that is sufficient to induce the release of other cytokines classically associated with mediating sickness responses, including TNF, IL-1, and IL-6 (8, 9). Progress in understanding these mechanisms has been arduous, because to date eight separate receptors have been implicated in mediating the cellular and biological responses to HMGB1: receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2, TLR4, TLR9, Mac-1, syndecan-1, phosphacan protein-tyrosine phosphatase-ζ/β, and CD24 (6, 10–15). HMGB1-TLR4 signaling has been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of sterile injury. TLR4-deficient animals are significantly protected from tissue injury during hepatic ischemia. Administration of anti-HMGB1 antibodies to wild-type mice confers significant protection against ischemia reperfusion injury, but administration of anti-HMGB1 antibodies to TLR4-deficient animals fails to confer protection (8). Thus far, the mechanisms underlying HMGB1-TLR4 binding and signaling in the pathogenesis of sterile injury have been unknown.

Previous studies in this field have been hampered by contamination of rHMGB1 with bacterial products, including endotoxin, which can bind to HMGB1 and interact with TLR4 to mediate cytokine release. In earlier work, we used endotoxin-free synthetic peptides to localize the TNF-stimulating domain of HMGB1 to within one of the two DNA-binding regions, termed the “B box” (3, 16). A synthetic 20-amino acid peptide-based B-box sequence is sufficient to mediate the cytokine stimulating activity of HMGB1. Here, we show that HMGB1-mediated induction of macrophage cytokine production requires binding to TLR4, and that binding and signaling are dependent upon a molecular mechanism that requires cysteine in position 106 within the B box.

Results

Mammalian HMGB1 Secreted by Genetically Engineered CHO Cells Activates Macrophage TNF Release.

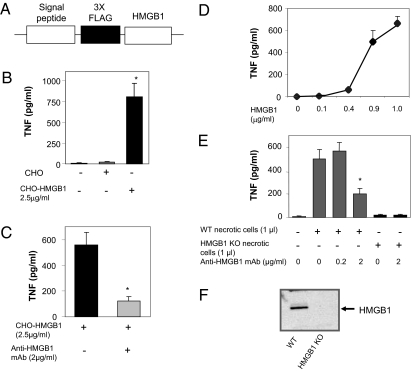

HMGB1 has been implicated as a cytokine mediator in the pathogenesis of a number of inflammatory diseases, including sepsis, arthritis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and colitis (6). To circumvent potential issues of bacterial contaminants or impurities attributable to recombinant bacterial-derived proteins, here we constructed a mammalian tumor cell line (CHO) that continuously secretes HMGB1 (10) (Fig. 1 A–D). We harvested the conditioned media from CHO cells that had been genetically engineered to spontaneously secrete HMGB1 (Fig. 1B). Exposure of this conditioned media to human macrophages significantly stimulated TNF release, as compared with media conditioned by exposure to control CHO cells (Fig. 1 B and D). Importantly, neutralizing monoclonal anti-HMGB1 antibodies (2G7) significantly inhibited TNF release induced by conditioned media from CHO cells secreting HMGB1, indicating that stimulation of TNF by mammalian HMGB1 is specific (Fig. 1C). The minimal HMGB1 concentration required to stimulate significant TNF release was ≈400 ng/mL, well within the concentration range that has been observed in the serum of septic patients, and in the joint fluid of rheumatoid arthritis patients (Fig. 1D) (17–19).

Fig. 1.

Mammalian HMGB1 secreted by genetically engineered CHO cells activates macrophage TNF release and is significantly inhibited by neutralizing anti-HMGB1 mAb. (A) A eukaryotic expression plasmid was engineered to secrete an N-terminal 3 X FLAG-tagged rat HMGB1 recombinant protein (24). Stably transfected CHO cells were cultured in CHO-S-SFM II media supplemented with 300 μg/mL geneticin. As control, non-HMGB1-secreting CHO cells were maintained in the same culture medium without geneticin. (B) Conditioned medium from CHO- or CHO-HMGB1-secreting cells was harvested and concentrated about 10-fold using a 10-KDa cut off membrane. TNF-stimulating activity of the conditioned medium was assayed on human primary macrophages in 96-well plates. Supernatants were collected after 16 h and TNF levels were quantified using commercial ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. unstimulated control. (C) Primary human macrophages were stimulated with conditioned medium from CHO-HMGB1 cells in the presence or absence of anti-HMGB1 mAb. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. CHO-HMGB1 alone. (D) Human primary macrophages were stimulated with various amounts of conditioned medium from CHO-HMGB1 cells (0, 2, 8, 18 and 20 μl/mL, corresponding to 0, 0.1, 0.4, 0.9 and 1 μg HMGB1/mL, respectively, as measured by Western blot). TNF levels in the supernatants were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5). (E) RAW 264.7 cells were treated with necrotic HMGB1 KO or wild-type fibroblasts (106 cells/mL) in the presence or absence of anti-HMGB1 mAb for 16 h. TNF levels in the supernatant were analyzed by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5–6). *P < 0.05 vs. WT necrotic cells alone. (F) Western blot autoradiogram of HMGB1 from wild-type and HMGB1 KO fibroblasts. Approximately 20 μg of total proteins from necrotic HMGB1 KO or wild-type fibroblasts were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-HMGB1 antibodies. Data shown is representative from two separate measurements.

Next, we prepared fibroblast lysates by freeze-thawing. As expected from earlier results (20, 21), exposure of macrophages to cellular debris from wild-type fibroblasts significantly stimulated TNF release. Lysates prepared from cells devoid of HMGB1, however, failed to activate TNF release (Fig. 1 E and F). Addition of neutralizing anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibodies to wild-type cell lysates significantly inhibited TNF release. When analyzed in the context of the results using HMGB1 knock-out (KO) cells, which indicated that >95% of the TNF induction is dependent upon HMGB1, the anti-HMGB1 antibody used neutralized ≈66% of the activity. Together, these results indicate that HMGB1 derived from mammalian cells and devoid of bacterial products is necessary and sufficient to activate macrophage-dependent TNF release, and that this can also be used as the basis for assessing the neutralizing activity of antibodies.

TLR4 Is Required for HMGB1 Signaling in Macrophages.

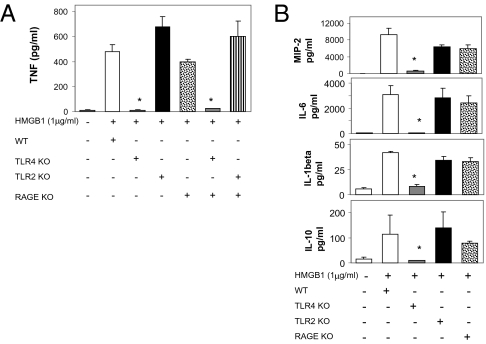

Previous work implicated TLR2, TLR4, and RAGE in mediating signal transduction by HMGB1 to stimulate cytokine release from macrophages (6, 11, 12). To determine whether HMGB1-dependent activation of macrophage cytokine release requires these receptors, we harvested thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages from wild-type and receptor KO mice. TNF release was significantly inhibited in macrophages from TLR4 KO mice. We observed that exposure of these macrophages to HMGB1 induced TNF production by macrophages derived from TLR2 KO and RAGE KO in quantities comparable to wild-type macrophages (Fig. 2A). TNF release was significantly inhibited in macrophages from TLR4 KO mice. An identical pattern was observed for other HMGB1-induced cytokine mediators in these macrophages, because the TLR4 KO macrophages also failed to produce MIP-2, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-10, whereas these were produced normally by TLR2 and RAGE KO macrophages (Fig. 2B). HMGB1 activation of macrophages from double KO of TLR2 and RAGE led to significant stimulation of TNF release, but double KO of TLR4 and RAGE completely prevented TNF release in response to HMGB1 (Fig. 2A). Thus, TLR4 is required for HMGB1-dependent activation of TNF release in macrophages, whereas RAGE and TLR2 are dispensable.

Fig. 2.

TLR4 is required for HMGB1 signaling on macrophages. Thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were isolated from wide-type (WT) or RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4 KO, or RAGE/TLR2 and RAGE/TLR4 double KO mice and stimulated with 1 μg/mL HMGB1 for 16 h. Supernatants were analyzed for levels of TNF (A), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and MIP-2 (B) by ELISA. Data shown are mean ± SEM (n = 4–5). *, P < 0.05 vs. WT.

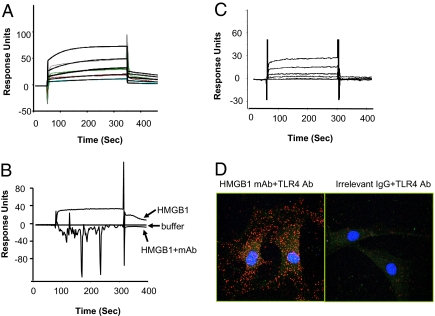

HMGB1 and B Box Bind to TLR4/MD2 Complex.

TLR4 and HMGB1 binding was analyzed by surface plasmon resonance technology. TLR4/MD2 complexes were coated on the sensor chip, then probed with recombinant HMGB1 or B box (Fig. 3 A–C). We observed significant HMGB1 binding to TLR4/MD2 in a concentration-dependent manner, with an apparent Kd of 1.5 μM (Fig. 3A). Notably, neutralizing anti-HMGB1 mAb significantly inhibited HMGB1-TLR4/MD2 binding, indicating that HMGB1 binding to TLR4/MD2 is specific (Fig. 3B). We had previously localized the macrophage TNF stimulating region of HMGB1 to one of two DNA binding domains within the HMGB1, the B box (3, 16). Here, we observed that recombinant B box binds specifically to TLR4/MD2 in a concentration-dependent manner, with an apparent Kd of 22 μM (Fig. 3C). To assess the binding interaction of HMGB1 to TLR4/MD2 in intact cells, we used the proximity ligation method (22) (Fig. 3D). Synovial fibroblasts harvested from rheumatoid arthritis patients spontaneously secrete HMGB1, and these cells were subjected to proximity ligation assay using anti-HMGB1 and anti-TLR4 antibodies. The secondary antibodies were modified by addition of complementary oligonucleotides capable of interacting when in close proximity, an event that was detected by PCR amplification using a fluorochrome-based detection method. We observed that endogenous HMGB1 colocalized with TLR4, and that the majority of binding interactions were localized within the cytoplasm (Fig. 3D), suggesting that HMGB1 is internalized with the TLR4 complex after cell surface binding. Together, these results indicate that HMGB1 interacts specifically with TLR4/MD2 and activates macrophages to produce TNF and other cytokines.

Fig. 3.

HMGB1 and B box bind to TLR4/MD2 as revealed by surface plasmon resonance (BIAcore) (A–C) and in situ proximity ligation assay (for HMGB1 only, D). (A) Different concentrations of HMGB1 (0, 0.0625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM) were flowed over immobilized TLR4/MD2 on the sensor chip. Data are presented as response units over time (seconds). HMGB1 bound to TLR4/MD2 in a concentration-dependent manner; with an apparent Kd of 1.5 μM. Data shown are representative of three experiments. (B) Compared with buffer alone, HMGB1 (10 μM) bound to TLR4/MD2 complex. Addition of neutralizing anti-HMGB1 mAb (10 μM) completely inhibited HMGB1 binding to TLR4/MD2. Data are representative of three experiments. (C) Increasing concentrations of B box (0, 0.0625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM) were flowed over immobilized TLR4/MD2 on the sensor chip. HMGB1 B box showed a concentration-dependent binding to TLR4/MD2 complex with a Kd of ≈22 μM. Data shown are representative of three experiments. (D) Synovial fibroblasts from human rheumatoid arthritis patients were subjected to in situ proximity ligation assay (Materials and Methods), using primary antibody pairs of anti-HMGB1 or control IgG2b antibody together with anti-TLR4 antibody. Dual binding by a pair of corresponding proximity probes, secondary antibodies with attached oligonucleotides, generates a spot (blob) if the two antibodies are in close proximity. Thus, each individual blob represents HMGB1 in close proximity with TLR4. The cells were counterstained with anti-actin (green) and Hoechst dye (blue) to visualize the cytoplasm and nucleus, respectively. Data shown are representative of three experiments.

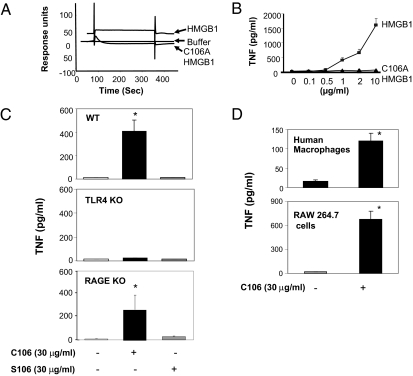

Cysteine at Position 106 Is Required for HMGB1 Binding and Activation of TNF Release.

We had previously localized the macrophage TNF stimulating activity of HMGB1 to a 20-mer peptide stretch within the B-box domain that contains a cysteine at postion 106 (16). Kazama and colleagues recently observed that mutation of this cysteine altered the immunogenic activity of HMGB1 (23). To address the possibility that this cysteine might influence the TNF-inducing activity of HMGB1, we produced HMGB1 containing alanine at position 106, instead of cysteine (C106A) (Materials and Methods). The C106A HMGB1 failed to bind TLR4/MD2 in the surface plasmon resonance studies, and as predicted from this result, addition of C106A to macrophage cultures failed to stimulate TNF release (Fig. 4 A and B). To study the molecular mechanism of signaling, we produced wholly synthetic peptides covering the first 20 amino acids of the B box (corresponding to HMGB1 residues 89–108, C106) and peptides in which cysteine 106 was substituted with serine (S106). As expected, addition of the C106 peptide to macrophages significantly activated TNF release from wild-type and RAGE KO cells, but not from TLR4 KO cells (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the C106 peptide activated human primary macrophages and murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells to produce TNF (Fig. 4D), but S106 peptide failed to stimulate TNF release by any macrophages. Together, these results give direct evidence that HMGB1 cysteine 106 is required for TLR4 binding and HMGB1-dependent cytokine release from macrophages.

Fig. 4.

Cysteine 106 is required for HMGB1-TLR4 binding and activation of TNF release from macrophages. (A) HMGB1 (10 μM) bound to TLR4/MD2 as compared with buffer alone in surface plasmon resonance analysis (BIAcore). In contrast, C106A HMGB1 did not bind to TLR4/MD2. Data shown are representative of three repeats. (B) Mouse peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with increasing concentrations of HMGB1 or C106A HMGB1 for 16 h. TNF release was measured by ELISA. Data shown are means ± SEM (n = 3). (C) Peritoneal macrophages from WT, TLR4, or RAGE KO mice were cultured with C106 or S106 peptides at concentrations indicated for 16 h, and TNF released was measured. Data shown are mean ± SEM (n = 4–5). *, P < 0.05 vs. unstimulated controls. (D) Primary human macrophages and RAW 264.7 cells were treated with C106 peptide for 16 h and TNF released was measured. Data shown are mean ± SEM (n = 3–4). *, P < 0.05 vs. unstimulated controls.

Discussion

These results position HMGB1 at the intersection of the pathophysiological responses to both infectious and sterile inflammation, because it binds to TLR4 to trigger activation of the classic proinflammatory cascade that mediates sickness behavior. Extremely high levels of HMGB1 are produced in tissues and serum during both sterile and infectious diseases, which can account for significant activation of TLR4-dependent TNF release despite the relatively low binding affinity between these two highly conserved proteins (3, 6, 8, 12, 18, 19). Evolution likely favored activation of the innate immune system by endogenous HMGB1 as a mechanism to activate tissue repair, cell proliferation, and regeneration of wounded tissues. Predictably, this relatively low-grade response would be sufficient to confer a survival advantage, in part by activating the development of sickness syndrome. Infection of the wound by pathogens however, would lead to a different story, one complicated by activation of a significantly more robust cytokine response required to prevent microbial spread. This result can inevitably be associated with the release of significantly higher levels of cytokines that are capable of mediating shock and tissue injury.

This mechanistic understanding of HMGB1-TLR4 interaction in the pathophysiology of inflammation has significant implications for designing therapeutics to suppress HMGB1-mediated tissue injury and impaired organ function. Anti-HMGB1 antibodies are proven to be highly effective in conferring protection against tissue injury in animals with lethal sepsis, endotoxemia, collagen-induced arthritis, cerebral ischemia, ischemia reperfusion injury in liver and heart, and in experimental colitis (reviewed in ref. 6). Development of these antibodies in the past has been hampered by the absence of knowledge about the relative importance of specifically inhibiting HMGB1 signaling through numerous candidate receptors. The majority of evidence has focused on the interactions of HMGB1 with RAGE, responses that are clearly important in stimulating neurite outgrowth, mediating smooth-muscle migration, and activating mechanisms of cell growth and movement. But these signals have not been directly implicated in the development of sickness syndrome during either infectious or sterile inflammation. By focusing on the TLR4-cytokine axis in macrophages, it will be possible now to study the mechanisms exerted by additional factors that have been implicated as synergistic cofactors to HMGB1 signaling, including LPS, IL-1β, nucleosomes, and DNA. Moreover, it should now be possible to design and develop therapeutics to inhibit HMGB1-mediated inflammation by specifically targeting HMGB1-TLR4 interactions to inhibit activation of cytokine release and sickness syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

Human TLR4/MD2 complex was obtained from R & D Systems Inc.. LPS (Escherichia coli, 0111:B4), Triton X-114, DMSO, and human macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) were purchased from Sigma. Ultra pure E. coli LPS was obtained from InvivoGen (Cat # tlrl-pelps). Recombinant mouse IL-6 was from BioSource International. Isopropyl-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was from Pierce. Thioglycollate medium was purchased from Becton Dickinson Co. FBS with ultra-low IgG was obtained from Gibco BRL. DNase I and 2-YT medium were obtained from Life Technologies.

Preparation of HMGB1 Proteins and Peptides.

HMGB1 and C106A HMGB1 mutant protein.

Recombinant rat HMGB1 was expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity as previously described (2, 24). Briefly, HMGB-1 was cloned by DNA amplification from Rat Brain Quick-Clone cDNA (Clontech). The PCR product was subcloned into the pCAL-n vector with a calmodulin binding protein (CBP) tag (Stratagene). For generating C106A mutant HMGB1, cysteine at position 106 in the wild-type HMGB1 clone was substituted with alanine using the QuikChange, Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The primers used were, forward: GCC TTC TTC TTG TTC GCT TCT GAG TAC CGC CC, and reverse: GGG CGG TAC TCA GAA GCG AAC AAG AAG AAG GC. The PCR product was also subcloned into the pCAL-n vector with a CBP tag. The plasmids of wild-type and mutated HMGB1 were transformed into protease-deficient E. coli strain BL21 (Novagen) and incubated in 2-YT medium. Fusion protein expression was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG. HMGB1 proteins were isolated by using calmodulin sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare). DNase I was added at 100 U/mL to the beads to remove any contaminating DNA. Degradation of DNA was verified by ethidium bromide staining of agarose gel containing HMGB1 proteins before and after DNase I treatment. The purity and integrity of purified HMGB1 proteins was verified by Coomassie blue staining after SDS/PAGE, with purity predominantly above 90%. No DTT was added in any of the buffers used for purification or storage of the proteins.

HMGB1 B box.

Recombinant B box was expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity as previously described (3, 16, 24). Briefly, B box was cloned by PCR amplification from a human brain Quick-Clone cDNA (Clontech). The PCR product was subcloned into an expression vector (pGEX) with a GST tag (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). B-box protein was isolated using glutathione sepharose 4B resin. DNase I was added to the beads to remove any contaminating DNA. The B box was purified by cleavage from GST tag using preScission protease as described (24). The purity and integrity of purified B-box protein was verified by Coomassie blue staining after SDS/PAGE, with purity predominantly above 90%.

C106 and S106 peptides.

A 20-mer C106 peptide (sequence: FKDPNAPKRLPSAFFLFCSE, corresponding to amino acids 89–108 in HMGB1 protein) and a 20-mer S106 peptide, with cysteine at 106 position changed to serine (sequence: FKDPNAPKRLPSAFFLFSSE) were purchased from AnaSpec Inc. The peptides were purified to 90% purity as determined by HPLC. Endotoxin was not detectable in the synthetic peptide preparations as measured by Limulus assay. The peptides were first dissolved in DMSO and further diluted in PBS as instructed by the manufacturer (AnaSpec), and prepared freshly before use.

Generation of CHO-HMGB1-Secreting Clone and Production of HMGB1 in CHO Cells.

A eukaryotic expression plasmid (psF-HMGB1) was engineered to secrete an N-terminal 3 X FLAG-tagged rat HMGB1 recombinant protein. The details of the cloning procedure have been described previously (10, 24). Plasmid psF-HMGB1 was transfected into CHO cells [CHO-AA8, American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)] and HMGB1-secreting cell line was cultured in CHO-S-SFM II media supplemented with 300 μg/mL geneticin (Invitrogen). HMGB1 was secreted at ≈5 μg/mL of conditioned medium. Supernatants from CHO- or CHO-HMGB1-secreting cells were concentrated using 10-KDa cut off membranes (Amicon Ultra, Millipore Co.) before adding to macrophage cultures for stimulation. No detectable amount of LPS was observed in cell supernatants as measured by Limulus assay.

LPS Removal from HMGB1 Protein Preparations.

Contaminating LPS from protein preparations was removed by Triton X-114 extraction as described previously (24). The LPS content in the protein preparations was measured by the chromogenic limulus assay (Lonza, Inc.). Typically, LPS content in the protein preparations was less than 1 pg LPS/μg protein.

Generation and Production of Neutralizing Anti-HMGB1 Monoclonal Antibody.

Anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) was generated as described previously (21). The neutralizing activity of anti-HMGB1 mAbs was assessed by the ability of mAb to attenuate HMGB1 induced TNF release by macrophage cultures. One of the hybridoma clones (2G7) with highest HMGB1 neutralizing activity was selected and expanded in culture. The epitope for 2G7 was mapped binding between amino acids 53 and 63 of HMGB1 (21).

For production of anti-HMGB1 mAb, 2G7 was grown to confluency in DMEM containing 10% FBS (ultra low IgG), 5 × 10−5M 2-Mecaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 20 pg/mL IL-6. The hybridoma conditioned medium was harvested 10 d after cells became confluent. The antibody was purified using HiTrap protein A HP column according to manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare). This antibody binds to HMGB1 in its native form as demonstrated by ELISPOT assay (25). The neutralizing activity of every batch of anti-HMGB1 mAb preparations was assessed in macrophage cultures by the ability of monoclonal antibody to attenuate HMGB1 induced TNF release (21). This antibody has been extensively used by us and other investigators to neutralize HMGB1 activity both in in vitro and in vivo studies. The neutralizing activity of anti-HMGB1 mAb have been tested in cell-culture assays and in animal models of HMGB1-mediated damage, such as sepsis (21).

Cell Isolation and Culture.

Mouse peritoneal macrophages.

Wild-type or receptor KO mice (7–12 wk old) were injected with 2 mL of sterile 4% thioglycollate broth intraperitoneally to elicit peritoneal macrophages as previously described (26). Animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation 48 h later, and cells were collected by lavage of the peritoneal cavity with 5 mL of sterile 11.6% sucrose. After washing, cells were resuspended in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM glutamine (Biowhittaker) and 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were seeded in 96-well Primaria tissue culture dishes (Life Technologies) and allowed to rest for 18 to 24 h. All treatments were carried out in serum free Opti-MEM I medium (Life Technologies).

Human macrophages.

Peripheral-blood mononuclear cells were isolated from the blood of normal volunteers (Long Island Blood Services) over a Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia Biotech) density gradient. Human primary monocytes were isolated by adherence and allowed to differentiate into macrophages for 7 d in complete DMEM medium containing 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 1 ng/mL M-CSF in 96-well culture plate at 105 cells/well. All experiments were carried out in serum-free Opti-MEM I medium.

RAW 264.7 cells.

Murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were used at 90% confluence and treatment was carried out in serum-free Opti-MEM I medium.

HMGB1 KO fibroblasts.

Wild-type and HMGB1 knock out fibroblasts were purchased from HMGBiotech, Inc. Cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2-mecaptoethanol (5 × 10−5 M), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10 mM Hepes. Necrotic cells were induced by three cycles of freezing and thawing (21). Necrosis was verified by microscopic evaluation showing cell fragments but no intact cells.

Animals.

Receptor gene KO mice.

TLR2, TLR4 and RAGE KO, and TLR2/RAGE and TLR4/RAGE-double KO mice were obtained from Helena Erlandsson-Harris (Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden) and were maintained at The Feinstein Institute for Medical research. Because the KO mice are derived from C57BL/6 mice, small colonies of wild-type C57BL/6 (Jackson Laboratory) were maintained under the same conditions. All animal procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of the Feinstein Institute. Mice were housed in the animal facility of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research under standard temperature, and light and dark cycles.

Tail clipping and genotyping.

To ascertain that newly bred animals had the expected gene deficiencies, we carried out genotyping on genomic DNA obtained from tail snips (27–29). Genomic DNA was extracted using a REDExtract-N-Amp Tissue PCR kit (Sigma, Catalog XNATS). PCR primers for genotyping were obtained from Invitrogen Inc. The PCR primers used were: RAGE (675 bp) forward: CGA GAT GGG AGA TGG GGG CAG GGT AGA, and reverse: ACC ATT GGG GAG GAT TCG AGC CAC GCT GTC. TLR2 (900 bp) forward: GTT TAG TGC CTG TAT CCA GTC AGT GCG, and reverse: TTG GAT AAG TCT GAT AGC CTT GCC TCC. TLR4 (1,300 bp) forward: TGT TGC CCT TCA TGC ACA GAG ACT CTG, and reverse: CGT GTA AAC CAG CCA GGT TTT GAA GGC. GFP (1,085 bp, positive control for RAGE KO) forward primers are the same as forward primers for RAGE. GFP reverse primer: CGT AAA CGG CCA CAA GTT CAG. Neo (700 bp, positive control for TLR2 and TLR4 KO), forward primers: TCA GAA GAA CTC GTC AAG AAG GCG, and reverse primer: ATG ATT GAA CAA GAT GGA TTG CAC. The PCR amplification conditions include 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 58 °C for 1 min (62 °C for 1 min for RAGE PCR), and 72 °C for 1.30 min, followed by 7 min at 72 °C (Applied Biosystems).

Cytokine Measurements.

HMGB1 levels were measured by Western immunoblotting analysis as previously described (3). Cell conditioned medium (100–200 μL) were first concentrated using centricon 10 (Millpore Corp.). Proteins from elute, or lysate from wild-type or HMGB1 KO cells were fractionated by SDS/PAGE, transferred to PVDF Immunoblot membrane (Bio-Rad), and probed with polyclonal anti-HMGB1 antibodies (purified IgG at 5 μg/mL final concentration) (3, 21). The levels of HMGB1 were calculated with reference to standard curves generated with purified HMGB1.

TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and MIP-2 released in the supernatants of macrophage cultures were measured by commercially available ELISA kits according to the instructions of the manufacturer (R&D Systems Inc.).

Surface-Plasmon Resonance Analysis (BIAcore).

Analysis of binding of HMGB1 proteins or B box to TLR4/MD2 complex was conducted using BIAcore 3000 instrument (BIAcore Inc.). Binding reactions were done in HBS-EP buffer from BIAcore, containing 10 mM hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 and 0.005% surfactant p20, pH 7.4. The CM5 dextran chip (flow cell 2) was activated with injection of 35 μL of 0.1 M N-ethyl-N'-[3-diethylamino-propyl]-carbodiimide and 0.1 M N-hydroxysuccinimide. TLR4/MD2 protein was coated on the surface of a CM5 dextran sensor chips by direct immobilization. An aliquot of 100 μL of 10 μg/mL dilution of human TLR4/MD2 protein in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5 was injected into flow cell-2 of CM5 chip to get the levels of 650 resonance units for the immobilization, followed by 35-μL injection of 1 M ethanolamine, pH 8.2 to block the remaining active sites. The flow cell-1, without immobilized TLR4/MD2 coated, was activated and blocked and used to evaluate nonspecific binding. The binding analyses were performed at flow rate of 30 μL/min at 25 °C. To evaluate binding, the analytes (60 μL each of HMGB1, B box or C106A HMGB1, 0–10 μM) were injected into flow cell-1 and -2 and the association of analyte and ligand was recorded respectively by surface-plasmon resonance. As a negative control, GST protein was injected under the same conditions as B box. The signal from the blank channel (flow cell-1) was subtracted from the channel containing purified TLR4/MD2 proteins (cell 2). Results were analyzed using the software BIAeval 3.2 (BIAcore Inc.). For all samples, a blank injection with buffer alone was subtracted from the resulting reaction surface data. Data were globally fitted to the Lagmuir model for a 1:1 binding.

Proximity Ligation Assay.

To investigate whether endogenous HMGB1 has the capability to interact with TLR4 we used in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA), which is a unique method developed to visualize subcellular localization and protein-protein interactions in situ (22). Human synovial fibroblasts were cultured on an eight-well object glass in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin, and streptomycin, fixed with 4% formaldehyde, and permeabilized with Triton. Cells were incubated over night with primary antibody pair of different species directed to HMGB1 (mouse IgG2b, 2G7) and to TLR4 (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz), respectively. In situ PLA was performed according to manufacturer's instructions (Olink Bioscience). Briefly, after incubation with primary antibodies, the cells were incubated with a combination of corresponding PLA probes, secondary antibodies conjugated to oligonucleotides (mouse MINUS and rabbit PLUS). Subsequently, ligase was added forming circular DNA strands when PLA probes were bound in close proximity, along with polymerase and oligonucleotides to allow rolling circle amplification. Fluoroscently labeled probes complementary in sequence to the rolling circle amplification product was hybridized to the rolling circle amplification product (Duolink Detection Kit 563; Olink Bioscience). Thus, each individual pair of proteins generated a spot (blob) that could be visualized using fluorescent microscopy. Images were taken using a Leica confocal laser scanning microscope.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between treatment groups were determined by Student's t test; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, General Clinical Research Center (M01RR018535), The National Institute for General Medical Science (to K.J.T.), and the Swedish Medical Research Council (to U.A. and H.E.-H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Andersson U, et al. High mobility group 1 protein (HMG-1) stimulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;192:565–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H, et al. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang H, et al. Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434651100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erlandsson Harris H, Andersson U. Mini-review: The nuclear protein HMGB1 as a proinflammatory mediator. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1503–1512. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotze MT, Tracey KJ. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1): nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:331–342. doi: 10.1038/nri1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang H, Tracey KJ. Targeting HMGB1 in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson U, Harris HE. The role of HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of rheumatic disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsung A, et al. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia-reperfusion. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1135–1143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lotze MT, et al. The grateful dead: Damage-associated molecular pattern molecules and reduction/oxidation regulate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:60–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu M, et al. HMGB1 signals through Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR2. Shock. 2006;26:174–179. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000225404.51320.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JS, et al. Involvement of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in cellular activation by high mobility group box 1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7370–7377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JS, et al. High mobility group box 1 protein interacts with multiple Toll-like receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C917–C924. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00401.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apetoh L, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13:1050–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian J, et al. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:487–496. doi: 10.1038/ni1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen GY, Tang J, Zheng P, Liu Y. CD24 and Siglec-10 selectively repress tissue damage-induced immune responses. Science. 2009;323:1722–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1168988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, et al. Structural basis for the proinflammatory cytokine activity of high mobility group box 1. Mol Med. 2003;9:37–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angus DC, et al. GenIMS Investigators Circulating high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) concentrations are elevated in both uncomplicated pneumonia and pneumonia with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1061–1067. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259534.68873.2A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kokkola R, et al. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1: A novel proinflammatory mediator in synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2598–2603. doi: 10.1002/art.10540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein RS, et al. Cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway activity and High Mobility Group Box-1 (HMGB1) serum levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Med. 2007;13:210–215. doi: 10.2119/2006-00108.Goldstein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin S, et al. Role of HMGB1 in apoptosis-mediated sepsis lethality. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1637–1642. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Söderberg O, et al. Direct observation of individual endogenous protein complexes in situ by proximity ligation. Nat Methods. 2006;3:995–1000. doi: 10.1038/nmeth947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazama H, et al. Induction of immunological tolerance by apoptotic cells requires caspase-dependent oxidation of high-mobility group box-1 protein. Immunity. 2008;29:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, et al. Recombinant HMGB1 with cytokine-stimulating activity. J Immunol Methods. 2004;289:211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wähämaa H, et al. HMGB1-secreting capacity of multiple cell lineages revealed by a novel HMGB1 ELISPOT assay. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:129–136. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li W, et al. A cardiovascular drug rescues mice from lethal sepsis by selectively attenuating a late-acting proinflammatory mediator, high mobility group box 1. J Immunol. 2007;178:3856–3864. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liliensiek B, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) regulates sepsis but not the adaptive immune response. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1641–1650. doi: 10.1172/JCI18704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoshino K, et al. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeuchi O, et al. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity. 1999;11:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]