Abstract

Complex three-dimensional biophotonic nanostructures produce the vivid structural colors of many butterfly wing scales, but their exact nanoscale organization is uncertain. We used small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) on single scales to characterize the 3D photonic nanostructures of five butterfly species from two families (Papilionidae, Lycaenidae). We identify these chitin and air nanostructures as single network gyroid (I4132) photonic crystals. We describe their optical function from SAXS data and photonic band-gap modeling. Butterflies apparently grow these gyroid nanostructures by exploiting the self-organizing physical dynamics of biological lipid-bilayer membranes. These butterfly photonic nanostructures initially develop within scale cells as a core-shell double gyroid (Ia3d), as seen in block-copolymer systems, with a pentacontinuous volume comprised of extracellular space, cell plasma membrane, cellular cytoplasm, smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) membrane, and intra-SER lumen. This double gyroid nanostructure is subsequently transformed into a single gyroid network through the deposition of chitin in the extracellular space and the degeneration of the rest of the cell. The butterflies develop the thermodynamically favored double gyroid precursors as a route to the optically more efficient single gyroid nanostructures. Current approaches to photonic crystal engineering also aim to produce single gyroid motifs. The biologically derived photonic nanostructures characterized here may offer a convenient template for producing optical devices based on biomimicry or direct dielectric infiltration.

Keywords: biological meta-materials, organismal color, biomimetics, biological cubic mesophases

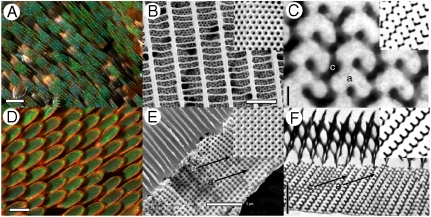

Organismal structural colors are produced by physical interactions of light with biomaterials having nanostructural variation in the refractive index on the order of visible wavelengths (1–6). Structural colors form an important aspect of the phenotype of butterflies (4, 5, 7, 8) and are frequently used in intersexual signaling (7), aposematic communication, etc. Structurally colored butterfly scales are extremely diverse in nanostructure and in optical function (4, 6, 8, 9). However, the structural colors of certain papilionid and lycaenid butterflies are produced by genuine three-dimensional biological photonic crystals comprised of a complex network of the dielectric cuticular chitin (refractive index, n = 1.56 + i0.06) (10) and air in the cover scales of the wing (8, 9) (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). The dorsal surface of the scales consists of a network of parallel, longitudinal ridges joined together by slender, spaced cross-ribs that together form windows into the interior of the scale (Fig. 1 B and E and Fig. S1 B, E, and H). The photonic crystals reside inside the body of the wing scales as either disjoint crystallites (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 E and H) or as a single slab of fused photonic crystal domains (4, 8, 9, 11) (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1B).

Fig. 1.

Anatomy of the structural color-producing nanostructure in lycaenid and papilionid butterflies. (A) Light micrograph of the ventral wing cover scales of Callophrys (formerly Mitoura) gryneus (Lycaenidae). The opalescent highlights are produced by randomly oriented crystallite domains. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (B) SEM image of the dorsal surface of a C. gryneus scale showing disjoint crystallites beneath windows created by a network of parallel, longitudinal ridges and slender, spaced cross-ribs. (Inset) Simulated SEM (111) projection from a thick slab of a level set single gyroid nanostructure. (Scale bar: 2.5 μm.) (C) TEM image of the C. gryneus nanostructure showing a distinctive motif, uniquely characteristic of the (310) plane of the gyroid morphology. (Inset) A matching simulated (310) TEM section of a level set single gyroid model. (Scale bar: 200 nm.) (D) Light micrograph of the dorsal wing cover scales of the Parides sesostris (Papilionidae). (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (E) SEM image of the lateral surface of the wing scale nanostructure of P. sesostris showing fused polycrystalline domains beneath columnar windows created by a network of ridges and spaced cross-ribs. The fractured face features a square lattice of air holes in chitin. (Inset) Simulated SEM (100) projection from a thick slab of a level set single gyroid nanostructure. (Scale bar: 2 μm.) (F) TEM image of the P. sesostris nanostructure showing a distinctive motif, uniquely characteristic of the (211) plane of the gyroid morphology. (Inset) A matching simulated (211) TEM section of a level set single gyroid model. (Scale bar: 2 μm.) c, chitin; a, air void.

A precise characterization of color-producing biological nanostructures is critical to understanding their optical function and development. Structural and developmental knowledge of biophotonic materials could also be used in the design and manufacture of biomimetic devices that exploit similar physical mechanisms of color production (4, 12, 13). After millions of years of selection for a consistent optical function, photonic crystals in butterfly wing scales are an ideal source to inspire biomimetic technology. Indeed, their optical properties have at times surpassed those of engineered solutions (4, 14).

The three-dimensional crystalline complexity of papilionid and lycaenid butterfly scales has been appreciated since the 1970s (8, 11, 15–24). However, most studies have used 2D electron microscopy (EM) to characterize these 3D photonic nanostructures, which is not sufficient to completely resolve their mesoscale features. These structures have been variously characterized as simple cubic (SC) (17), face-centered cubic (FCC) (16), or FCC inverse opal (22, 24) orderings of air spheres in chitin. Recently, Michielsen and Stavenga (18) reported qualitative pattern matching between published transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of various papilionid and lycaenid structurally colored wing scales and simulated sections of level set gyroid computer models. Michielsen and Stavenga (18) stated that additional comparisons of the butterfly nanostructures to computer models of primitive cubic (P) and diamond (D) structures “immediately suggest” a best fit with the gyroid structure, but they did not present these results nor any quantitative measure of the matches to alternative cubic symmetry space groups (P, D, G). More recently, Michielsen et al. (20) provided further support for their identification of the gyroid nanostructure in Callophrys rubi (Lycaenidae) by showing congruence between a finite difference time domain model of light scattering by a single gyroid structure and single scale reflectance measurements. Argyros et al. (23) used tilt-series electron tomography to model the nanostructure of Teinopalpus imperialis (Papilionidae) and concluded that it was a distorted, chiral, tetrahedral structure with an underlying triclinic lattice. Poladian et al. (19) and Michielsen and Stavenga (18) respectively suggest a distorted diamond and gyroid morphology for T. imperialis. Although electron tomography may be promising, sample shrinkage and other artifacts may alter the nanostructure and its three-dimensional connectivity (23, 25). Thus, fundamental uncertainty remains about the precise nanoscale organization of 3D photonic crystals in butterfly wing scales.

Synchrotron small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) is an ideal tool to investigate surface and bulk structural correlations of artificially engineered photonic crystals (26). However, SAXS has only recently (27) been applied to characterize natural photonic materials with mesoscale (150–350 nm) scattering features, given that the larger lattice parameters involved require even smaller scattering angles and advanced X-ray optics (28). Here we apply pinhole SAXS, extended to very small scattering angles, to characterize the photonic crystal nanostructures on the wing scales of five well-studied butterflies: Parides sesostris, Teinopalpus imperialis, (Papilionidae); Callophrys (formerly Mitoura) gryneus, Callophrys dumetorum, and Cyanophrys herodotus (Lycaenidae) (Fig. 1, Fig. S1, and Table S1).

Results and Discussion

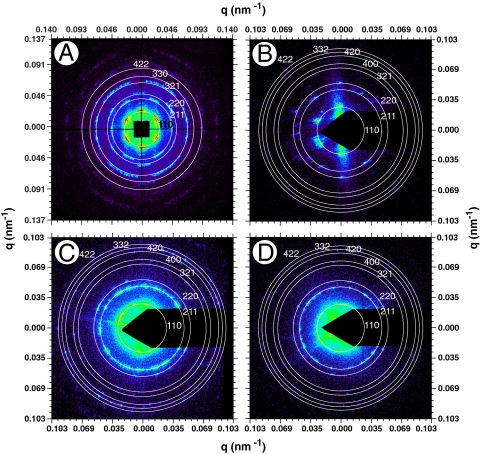

The SAXS patterns of all five species (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2) consist of a number of discrete spots of high intensity, arranged in concentric circles. Each spot is the Bragg scattering peak from one crystal plane with a given orientation to the X-ray beam. The large number of spots observed and the irregular angles between them indicate that there are a number of distinctly oriented crystallite domains within the illuminated sample volume, consistent with SEM observations (Fig. 1 B and E and Fig. S1 B, E, and H) and the size of the X-ray beam used (15 × 15 μm). Scattering intensity profiles (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3) of P. sesostris, T. imperialis, C. gryneus, C. dumetorum, and C. herodotus, azimuthally integrated from the respective SAXS patterns, reveal discrete Bragg peaks with the following scattering wave vector positional ratios, q/qmax:  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , where qmax is 0.0268, 0.0266, 0.0275, 0.0258, and 0.027 nm-1 for each species, respectively. These peaks were indexed as reflections from (110), (211), (220), (321), (400), (420), (332), (422), (431), and (521) planes [International Union of Crystallography (IUCr) International Tables for Crystallography; Figs. 2 and 3, and Figs. S2 and S3]. Accordingly, we assign the single gyroid (space group no. 214, I4132) crystallographic space group symmetry to the nanostructures of all five butterfly species. The SAXS peaks do not conform to the predictions from alternative cubic space groups such as simple primitive (Pm3m) or single diamond (Fd3m), as well (Fig. S3). After normalizing the fundamental peak to one, the conspicuous absence of the

, where qmax is 0.0268, 0.0266, 0.0275, 0.0258, and 0.027 nm-1 for each species, respectively. These peaks were indexed as reflections from (110), (211), (220), (321), (400), (420), (332), (422), (431), and (521) planes [International Union of Crystallography (IUCr) International Tables for Crystallography; Figs. 2 and 3, and Figs. S2 and S3]. Accordingly, we assign the single gyroid (space group no. 214, I4132) crystallographic space group symmetry to the nanostructures of all five butterfly species. The SAXS peaks do not conform to the predictions from alternative cubic space groups such as simple primitive (Pm3m) or single diamond (Fd3m), as well (Fig. S3). After normalizing the fundamental peak to one, the conspicuous absence of the  reflection and the presence of the forbidden

reflection and the presence of the forbidden  peak do not support the assignment of the simple primitive (Pm3m) space group (Fig. S3). Upon normalizing the fundamental peak to

peak do not support the assignment of the simple primitive (Pm3m) space group (Fig. S3). Upon normalizing the fundamental peak to  , the incongruence of the observed peaks with the predicted

, the incongruence of the observed peaks with the predicted  and

and  peaks, and the complete absence of features at the predicted

peaks, and the complete absence of features at the predicted  and

and  peak positions do not support the assignment of the single diamond (Fd3m) space group (29) (Fig. S3).

peak positions do not support the assignment of the single diamond (Fd3m) space group (29) (Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Representative 2D SAXS patterns (original image 1340 × 1300 pixels) for (A) Teinopalpus imperialis, (B) Parides sesostris, (C) Callophrys (Mitoura) gryneus, and (D) Cyanophrys herodotus. The false color scale corresponds to the logarithm of the X-ray scattering intensity. The radii of the concentric circles are given by the peak scattering wave vector (qmax) times the moduli of the assigned hkl indices, where h, k, and l are integers allowed by the single gyroid (I4132) symmetry space group (IUCr International Tables for Crystallography).

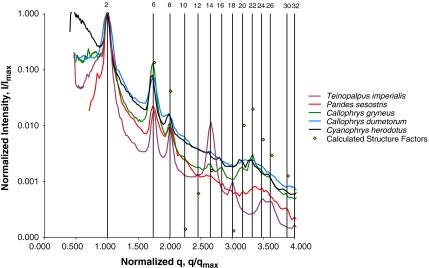

Fig. 3.

Normalized azimuthally averaged X-ray scattering profiles (Intensity I/Imax vs. scattering wave vector q/qmax) calculated from the respective 2D SAXS patterns for Teinopalpus imperialis, Parides sesostris, Callophrys (Mitoura) gryneus, Callophrys dumetorum, and Cyanophrys herodotus. The vertical lines correspond to the expected Bragg peak positional ratios for the single gyroid crystallographic space group (I4132). The numbers above the lines are squares of the moduli of the Miller indices (hkl) for the allowed reflections. The calculated, normalized structure factors for a single gyroid (I4132) level set model for C. herodotus, with 29% dielectric volume fraction and a lattice constant of 331 nm, is also shown alongside for comparison (yellow diamonds). (Also see Fig. S3).

The linearity and the zero intercepts of the plots of the reciprocal lattice spacings versus the moduli of the assigned Miller indices further confirm the cubic nature of the nanostructure (Fig. S4), but do not specifically discriminate among the possible cubic space groups. However, the slope of this plot gives an estimate of the unit cell lattice parameter (i.e., the length of a side of the cubic unit cell) for the nanostructure, which can be compared to estimates from EM images. The butterfly scale photonic nanostructures possess rather large lattice parameters (a > 300 nm) and the values we obtain are compatible with previously published estimates (18) (Table S2). The EM-estimated lattice parameters correspond much more closely to the SAXS estimates of the butterfly nanostructures, assuming a single gyroid space group, rather than a simple primitive (Pm3m, too small) or a single diamond (Fd3m, too large) symmetry (Fig. S4 and Table S2).

The SAXS spectra of the gyroid butterfly nanostructures do not all exhibit the theoretically allowed (310), (222), and (330) reflections of a single gyroid (Figs. 2 and 3, and Fig. S2). However, consistent with the SAXS data, the simulated structure factor (see Materials and Methods) of a level set single gyroid (I4132) structure with a 29% dielectric volume fraction and a lattice constant of 331 nm, has low intensity (222), (310), and (330) peaks (Fig. 3, yellow diamonds). From the FWHM of pseudo-Voigt fits to the first-order SAXS peaks, we calculated the approximate size ( ) of the butterfly crystallite domains (Table S1), which is in good agreement with TEM micrographs (Fig. 1 B and E and Fig. S1 B, E, and H). The presence of a large number of sharp, higher-order reflections, particularly for T. imperialis, C. gryneus, and C. herodotus (Figs. 2 and 3), is remarkable for a biological soft matter system and indicates a high degree of order within the nanostructure.

) of the butterfly crystallite domains (Table S1), which is in good agreement with TEM micrographs (Fig. 1 B and E and Fig. S1 B, E, and H). The presence of a large number of sharp, higher-order reflections, particularly for T. imperialis, C. gryneus, and C. herodotus (Figs. 2 and 3), is remarkable for a biological soft matter system and indicates a high degree of order within the nanostructure.

We generated computer models of the single gyroid, simple primitive, and single diamond nanostructures using level set approximations, and produced simulated TEM and SEM projections of appropriate thicknesses and chitin volume fractions (18) (Table S1), along various lattice directions/cleavage planes, including (110), (111), and (211). These simulations provide qualitative comparisons against actual EM images (Fig. 1, and Figs. S1 and S5). SEM images of all five butterfly scales revealed square (100) and triangular (111) lattices of circular air channels, consistent with the bicontinuous cubic symmetry of gyroid nanostructures (Fig. 1 B and E, and Fig. S1 B, E, and H). TEM images of the wing scales of all five species show diagnostic motifs that are characteristic of particular planes of the single gyroid space group, and not simple primitive or single diamond, thereby confirming the threefold network connectivity of the nanostructure (Fig. 1 C and F, and Figs. S1 C, F, and I and S5). These observations lend further confidence to our assignment of the single gyroid space group for the butterfly photonic crystal nanostructures.

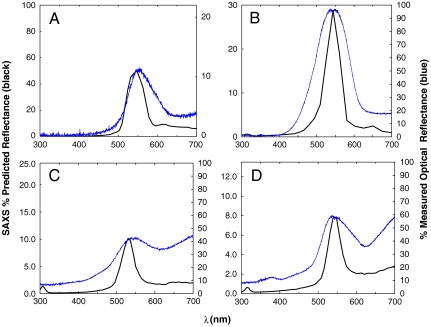

We used the SAXS structural data to predict the optical reflectance spectra of the respective cuticle nanostructures with single-scattering theory, as a first approximation (8, 30–32). We illuminated the nanostructures at normal incidence and measured the spectrum of directly back-scattered light (8). In this geometry, the scattering wave vector, q, and the wavelength of light, λ, are simply related as

|

[1] |

where 2π/q is the “d” spacing, and nav is the average or effective refractive index of the nanostructure (33). For each species, the optical and X-ray scattering peaks agree reasonably well (< ∼ 15 nm) with a value of 1.16 for nav, which corresponds to a chitin volume fraction of 0.25 (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2). These SAXS results are a substantial improvement over our previous, noisy, TEM-based 2D Fourier method (8).

Fig. 4.

Predicted reflectance (black line) from azimuthal average of SAXS patterns versus measured optical reflectance (blue line) for (A) Teinopalpus imperialis, (B) Parides sesostris, (C) Callophrys (Mitoura) gryneus, and (D) Cyanophrys herodotus. The SAXS predicted reflectance follows from Bragg’s law and is given by mapping the X-ray scattering intensity from scattering wave vector to wavelength space by choosing a value of 1.16 for the average refractive index, nav, which corresponds to a chitin volume fraction of 0.25. See text for details.

The breadth of the predicted reflectance peaks (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2) are a result of single scattering from multiple randomly oriented crystallite domains, which is captured by the azimuthal averages of the SAXS data. The broader widths of the measured reflectance spectra, however, are substantially wider than the single-scattering predictions. To examine whether the broad observed reflectance peaks are consistent with multiple scattering, we calculated the photonic bandgap structures of level set single network gyroid models for the butterfly nanostructures (Fig. S6 and Table S1). We optimized the bandgap calculations for the dielectric (chitin) filling fraction, so that the Γ-N (110) midgap frequencies matched a/λpk, where a is the lattice parameter measured using SAXS and λpk is the measured optical peak wavelength. In this way, we obtain more precise estimates of the average refractive index and chitin volume fractions for each species (Table S1). Our estimates of nav are also comparable to previous estimates based on electron micrographs (8, 18).

Bandgap calculations predict three relatively closely spaced pseudogaps or partial photonic bandgaps along Γ-N (110), Γ-P (111), and Γ-H (200) directions for the butterfly photonic nanostructures (Fig. S6 and Table S1). Independent Gaussian fits to the optical reflectance spectra for all five species coincide fairly well to these three corresponding partial bandgaps (Fig. 4 and Figs. S2, S6, and S7). Based on the midgap to gap-width ratios of the Γ-N (110) gap, we calculated the Bragg attenuation lengths of the butterfly nanostructures to be between 3.9–4.4 a (Table S1). Except for C. dumetorum, the average size of the crystallite domains is several times larger than the Bragg length of the corresponding nanostructure (Table S1). Along with the congruence of our photonic bandgap analyses to optical measurements (Fig. S7), this result suggests that most or all of the incident light is essentially reflected when the Bragg condition is satisfied, and that the broader reflectance spectra observed for the optical reflectance as compared to the SAXS single-scattering reflectance predictions is due to multiple scattering. C. gryneus and C. herodotus also appear to have additional longer wavelength reflectance due to absorption by pigments within the scales (Fig. 4).

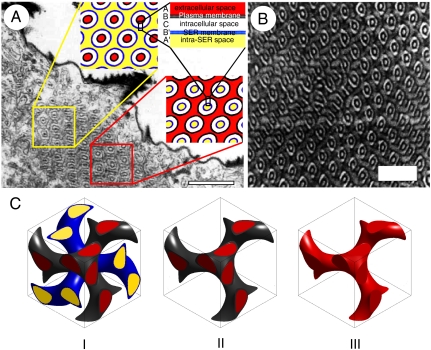

Understanding the development of these biophotonic nanostructures in butterflies may provide insights into possible biomimetic designs for the manufacture of photonic devices (4, 12, 13, 27). Using TEM images of scales from developing butterfly pupae, Ghiradella (11, 16, 21) described the development of the gyroid photonic nanostructure of Callophrys (formerly Mitoura) gryneus. Ghiradella demonstrated that the chitin-air nanostructure of the wing scales develops in an individual scale cell through the complex invaginated growth of the cellular plasma membrane and intracellular smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) (Fig. 5A). The infoldings of the scale cell’s plasma membrane define a continuous extracellular space that is inside the peripheral margin of the cell. The polysaccharide chitin is then deposited into this extracellular space. Once the cell dies, the cytoplasm evaporates and the membranes degrade, leaving behind a solid interconnected network of extracellular chitin in air. However, the exact topology of the developing plasma membrane network and the role of SER in the cell membrane invagination process has remained unclear (11, 21).

Fig. 5.

Development of butterfly wing scale photonic nanostructure. (A) TEM cross-section of a ventral wing scale cell from a 9-day-old C. gryneus pupa (from refs. 11 and 21), depicts the complex infolding of the plasma membrane and SER membrane. The developing nanostructure shows the diagnostic motif of two concentric rings roughly in a triangular lattice (compare with Fig.5B). Yellow and red boxes highlight areas revealing different sections through the (110) plane of a polarized (ABCB′A′) pentacontinuous core-shell double gyroid (color insets). (Scale bar: 1 μm.) (Inset) Colored model of a core-shell double gyroid of ABCB′A′ form: A (red) is the extracellular space, B (black) is the plasma membrane, C (white) is the cytoplasmic intracellular space, B' (blue) is the SER membrane, and A' (yellow) is the intra-SER space. [Reprinted with permission from ref. 11.) (B) OsO4-stained (110) TEM section of an ABC triblock copolymer with core-shell double gyroid morphology. (Scale bar: 200 nm.) (Reprinted with permission from ref. 40. Copyright 2005, John Wiley and Sons.) (C) Three-dimensional model of development of photonic butterfly wing scale cell. (I) Unit-cell volume rendering of the core-shell double gyroid model structure of the form ABCB′A′. Color of each component from inset in A. (II) Single gyroid composed of cell plasma membrane (black) surrounding extracellular space (red). (III) As the scale cell dies, the cellular cytoplasm and membranes (BCB′A′ blocks of the core-shell double gyroid) are replaced with air leaving behind a single gyroid core-shell network of chitin (red) in air.

Biological, lipid-bilayer membranes of living cells and intracellular organelles, especially the SER, exhibit the physical capacity to self-organize into a variety of complex, nano- to mesoscale structures including stacked lamellae, hexagonally arranged tubules, and bicontinuous cubic phases (with lattice constants of 50–500 nm) (34–36). Biological cubic membrane structures occur with double primitive (Im3m), double gyroid (Ia3d) and double diamond (Pn3m) space group symmetries (34, 35). These morphologies are the very same cubic bicontinuous phases seen in block-copolymer (29, 37), lyotropic lipid-water (38), and amphiphilic surfactant systems (39). The formation of complex cubic membrane structures in living cells have been hypothesized to be controlled biologically by the regulation of the expression of proteins that are intrinsic to and span the lipid-bilayer membrane (36). The energetics and dynamics of membrane curvature is thought to be mediated by the binding of intramembrane proteins of different molecular weights (36) and their electrostatic interactions (35). The double diamond and double gyroid nanostructures formed by biological cubic membranes self-organize through a combination of biological membrane growth and amphiphilic, thermodynamic interactions similar to those in lipid-water, block-copolymer, and other soft condensed matter systems. However, the single network gyroid (I4132) phase found in mature structurally colored butterfly scales has previously not been observed in any biological or synthetic systems.

Here we present a model for the development of the 3D photonic nanostructure in the wing scale cells of lepidopteran pupae. Based on published TEM images of the nanostructure in developing pupae of C. gryneus (11, 21) (Fig. 5A), we hypothesize that the cell plasma membrane and the SER membrane interact to form a pair of parallel lipid-bilayer membranes, separated by the cellular cytoplasm. The two parallel lipid-bilayer membranes of the developing scale cell form a pentacontinuous structure with a core-shell double gyroid morphology, similar to those seen in ABC triblock copolymer melts (40, 41) (Fig. 5 A and B). Exploiting the inherent biological differentiation between the intracellular and extracellular volumes of a cell, the lipid-bilayer membranes of developing butterfly photonic scale cells define the unique pentacontinuous volumes of a core-shell double gyroid (Ia3d) structure of the form ABCB′A′, in which A is the extracellular space, B is the plasma membrane, C is the cell’s cytoplasmic volume, B′ is the SER membrane, and A′ is the intra-SER space (Fig. 5A and Insets). As in a triblock copolymer system, the proposed ABCB′A′ core-shell double gyroid system in the butterfly scale has the lipid-bilayer membranes (B and B′) together with the intervening cytoplasmic space (C) forming the matrix phase (BCB′) of the system. The complexity of this biological double gyroid with distinctly differentiated core-shells can be appreciated more fully through a movie of serial sections from various angles (110, 210, and 100) through a computer model of the nanostructure (Movie S1). Following the development of the ABCB′A′ core-shell double gyroid structure (Fig. 5 C–I), chitin is deposited and polymerized in the extracellular space (A) that is now within the peripheral outline of the scale cell. This extracellular space forms the core of one of the gyroid networks (Fig. 5C, red), which is enclosed by the plasma membrane (Fig. 5C, black). As the cell dies, the cellular cytoplasm and the membranes (BCB′A′ blocks of the core-shell double gyroid) are replaced with air, leaving behind a single gyroid network of chitin (A) in air (Fig. 5C). We present a visualization of this transformation and the associated changes in structure factors of the developing nanostructure in Movie S2.

Published TEM images by H. Ghiradella (11, 16, 21) of a developing butterfly wing scale exhibit the diagnostic double gyroid motif of two concentric thick black rings arranged in a triangular lattice found in triblock-copolymers (Fig. 5 A and B). Sections through the (110) plane of a core-shell double gyroid model structure reproduces such a pattern (Fig. 5A and Insets, and Movie S1). Furthermore, the TEM section in Fig. 5A (from 11) strikingly shows two different regions through the (110) plane, confirming our model. To the right (Fig. 5A, red square), initial chitin deposition is visible as dark lines in the spaces surrounding the double rings, whereas on the left (Fig. 5A, yellow square), chitin rods are visible as dark spots in the center of the double rings.

The chirality of the resulting single gyroid nanostructure is not straightforward to ascertain from TEM or SAXS data (42). However, visual inspection of SEM images reveals clear examples of single gyroid networks with both left- and right-handed chiralities (Fig. S8). Although the original EM images were not all obtained in an unbiased manner, i.e., from multiple independent domains, it appears that both chiralities occur at similar frequencies, but further EM observations are necessary to confirm this. However, this implies that the initiation of gyroid chirality during development is random across the domains within a single scale cell, as hypothesized for symmetric amphiphilic systems (42).

Our developmental model proposes that the butterfly scale cells exploit the energetics of cubic membrane folding commonly seen in lipid-bilayer membranes of cellular organelles (34–36) to develop a single gyroid photonic nanostructures that are used in social and sexual communication (7) (Fig. 5). By initially developing the thermodynamically favored double gyroid nanostructure (29, 37–39), and then transforming it into the optically more efficient single gyroid photonic crystal (43, 44), these butterflies have evolved to use biological and physical mechanisms that anticipate contemporary approaches to the engineering and manufacture of photonic materials (43, 44). Current engineering approaches also aim to produce single gyroid motifs from a double gyroid template (e.g., ref. 45). The biological development of triply periodic, cubic, photonic crystals in butterflies may offer a convenient template for the design and manufacture of devices for photonic applications based on biomimicry or positive cast dielectric infiltration (43–45).

Interestingly, closely related species of lycaenid (11) and papilionid (8) butterflies have photonic nanostructures with a perforated lamellar morphology. Often described as laminar arrays, these nanostructures exhibit stacked perforations arranged in a brick-and-mortar pattern in TEM cross-sections (8, 46). Phase transitions between perforated lamellar to gyroid structures are well documented in block-copolymer systems (47). Thus, it is likely that the perforated lamellar morphology shares the same general membrane folding developmental mechanism that produces the gyroid morphology seen in these closely related species. Butterflies have apparently evolved a diversity of photonic nanostructures (4, 8, 9, 11) by using membrane energetics to arrive at different stable, self-assembled states.

Materials and Methods

Small Angle X-Ray Scattering.

Pinhole SAXS data on single butterfly wing scales (∼5–10-μm thick), which were mounted perpendicular to the X-ray beam on insect minuten pins, were collected at beamline 8-ID-I of the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Labs. We used a 15 × 15 μm beam (1.68 Å, 7.35 keV, 50 × 0.2 s exposures, sample-detector distance 3.56 m, flux 2.7 × 109 photons/s), in order to average over as few crystallite domains as possible. Azimuthally averaged scattering profiles were calculated from the SAXS patterns using the MATLAB-implemented software, XPCSGUI, provided by 8-ID, at 200 and 500 equal dq/q partitions, and with customized masks. For indexing the SAXS Bragg peaks, the original scattering wave vector positional ratios (q/qmax) from the azimuthal averages were renormalized by multiplying by (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3), as a normalized

(Fig. 3 and Fig. S3), as a normalized  peak is inconsistent with any cubic space group (48).

peak is inconsistent with any cubic space group (48).

Photonic Bandgap calculation.

We used the Massachusetts Institute of Technology photonic bandgap package (http://ab-initio.mit.edu/mpb) to calculate the first eight bands of single network gyroid photonic nanostructures in body-centered cubic basis, using various mesh sizes of 1–64 and resolutions of 16–128 to discretize the unit cell. The dielectric function was generated using the gyroid level set equation (49) (see SI Materials and Methods):

| [2] |

where the parameter t determines the volume fraction of the two gyroid networks on either side of the intermaterial dividing interface.

In order to simulate a single dielectric network gyroid structure, the dielectric function f(x,y,z) was chosen such that

| [3] |

where n(x,y,z) is the refractive index at the point (x,y,z) and t is the parameter from Eq. 2. The bandgap calculations were optimized for the dielectric (chitin) volume fractions by choosing the midgap frequencies of the Γ-N (110) gap as a/λpk, where a is the lattice parameter measured using SAXS and λpk is the measured optical peak wavelength (Table S1). We confirmed our photonic bandgap model by changing the value of the refractive index of the dielectric from 1.56 to 3.6 and the dielectric filling fraction to 50%, and reproducing the bandgap diagram calculated by Maldovan et al. (43) for this single gyroid photonic nanostructure.

Structure Factor Calculations.

We azimuthally integrated 3D Fourier transforms (25) of level set single gyroid network models generated in MATLAB using Eq. 2 and normalized the azimuthal averages to generate the calculated structure factors. We used lattice parameters and chitin filling fractions based on the SAXS data (Table S1). Eq. 2 is the first allowed structure factor term, F110, for a single gyroid structure with I4132 symmetry (49). The addition of higher-order terms (F211, F220), weighted by the corresponding relative SAXS intensities did not alter our results significantly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Hui Cao and Steven Johnson for help with bandgap calculations and Gil Toombes for help with gyroid structure factor calculations, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. This work was supported with seed funding from the Yale National Science Foundation (NSF) Materials Research Science and Engineering Center [Division of Materials Research (DMR) 0520495] and NSF grants to S.G.J.M. (DMR) and R.O.P. (Division of Biological Infrastructure), and Yale University funds to V.S. and R.O.P. Butterfly wing scale specimens were kindly provided by the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History and the University of Kansas Natural History Museum and Biodiversity Research Center. TEM images of butterfly scales were prepared by Tim Quinn. SAXS data were collected at beamline 8-ID-I at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Labs, and supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.0909616107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fox DL. Animal Biochromes and Structural Colors. 2nd Ed. Berkeley, CA: Univ. California Press; 1976. pp. 13–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nassau K. The Physics and Chemistry of Color: The Fifteen Causes of Color. 1st Ed. New York: Wiley; 1983. p. 454. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prum RO. Anatomy, physics, and evolution of avian structural colors. In: Hill GE, McGraw KJ, editors. Bird Coloration, Volume 1 Mechanisms and Measurements. Vol 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 2006. pp. 295–353. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vukusic P, Sambles JR. Photonic structures in biology. Nature. 2003;424(6950):852–855. doi: 10.1038/nature01941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker AR. Invertebrate structural colours. In: Savazzi E, editor. Functional Morphology of the Invertebrate Skeleton. London: Wiley; 1999. pp. 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivasarao M. Nano-optics in the biological world: Beetles, butterflies, birds, and moths. Chem Rev. 1999;99:1935–1961. doi: 10.1021/cr970080y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweeney A, Jiggins C, Johnsen S. Polarized light as a butterfly mating signal. Nature. 2003;423:31–32. doi: 10.1038/423031a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prum RO, Quinn T, Torres RH. Anatomically diverse butterfly scales all produce structural colours by coherent scattering. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:748–765. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vukusic P, Sambles JR, Ghiradella H. Optical classification of microstructure in butterfly wing-scales. Photon Sci News. 2000;6:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vukusic P, Sambles JR, Lawrence CR, Wootton RJ. Quantified interference and diffraction in single Morpho butterfly scales. P Roy Soc Lond B Bio. 1999;266(1427):1403–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghiradella H. Structure and development of iridescent butterfly scales: Lattices and laminae. J Morphol. 1989;202:69–88. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1052020106. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/35280/home. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker AR, Townley HE. Biomimetics of photonic nanostructures. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2(6):347–353. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez C, Arribart H, Giraud Guille MM. Biomimetism and bioinspiration as tools for the design of innovative materials and systems. Nat Mater. 2005;4(4):277–288. doi: 10.1038/nmat1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potyrailo RA, et al. Morpho butterfly wing scales demonstrate highly selective vapour response. Nat Photonics. 2007;1(2):123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghiradella H, Aneshansley D, Eisner T, Silberglied RE, Hinton HE. Ultraviolet reflection of a male butterfly: Interference color caused by thin-layer elaboration of wing scales. Science. 1972;178:1214–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4066.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghiradella H, Radigan W. Development of butterfly scales. II. Struts, lattices and surface tension. J Morphol. 1976;150:279–298. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris RB. Iridescence from diffraction structures in the wing scales of Callophrys rubi, the Green Hairstreak. J Entomol Ser A. 1975;49(2):149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michielsen K, Stavenga DG. Gyroid cuticular structures in butterfly wing scales: Biological photonic crystals. J R Soc Interface. 2008;5(18):85–94. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2007.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poladian L, Wickham S, Lee K. Iridescence from photonic crystals and its suppression in butterfly scales. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6(Suppl 2):S233–S242. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0353.focus. 10.1098/rsif.2008.0353.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michielsen K, De Raedt H, Stavenga DG. Reflectivity of the gyroid biophotonic crystals in the ventral wing scales of the Green Hairstreak butterfly, Callophrys rubi. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7(46):765–71. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghiradella H, Butler M. Many variations on a few themes: A broader look at development of iridescent scales (and feathers) J R Soc Interface. 2009;6:243–251. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0372.focus. 10.1098/rsif.2008.0353.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kertész K, et al. Gleaming and dull surface textures from photonic-crystal-type nanostructures in the butterfly Cyanophrys remus. Phys Rev E. 2006;74(2):021922. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.021922. Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Argyros A, Large MCJ, McKenzie DR, Cox GC, Dwarte DM. Electron tomography and computer visualization of a three-dimensional ‘photonic’ crystal in a butterfly wing-scale. Micron. 2002;33:483–487. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(01)00044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingram A, Parker A. A review of the diversity and evolution of photonic structures in butterflies, incorporating the work of John Huxley (The Natural History Museum, London from 1961 to 1990) Philos T R Soc B. 2008;363(1502):2465–2480. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2258. 10.1098/rstb.2007.2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shawkey M, et al. Electron tomography, three-dimensional Fourier analysis and color prediction of a three-dimensional amorphous biophotonic nanostructure. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6(Suppl 2):S213–S220. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0374.focus. 10.1098/rsif.2008.0353.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urbas BAM, Maldovan M, Derege P, Thomas EL. Bicontinuous cubic block copolymer photonic crystals. Adv Mater. 2002;14(24):1850–1853. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dufresne ER, Noh H, Saranathan V, Mochrie S, Prum RO. Self-assembly of amorphous biophotonic nanostructures by phase separation. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1792–1795. 10.1039/b902775k. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falus P, Borthwick MA, Mochrie SGJ. Fast CCD camera for X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy and time-resolved X-ray scattering and imaging. Rev Sci Instrum. 2004;75(11):4383–4400. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hajduk DA, et al. A reevaluation of bicontinuous cubic phases in starblock copolymers. Macromolecules. 1995;28:2570–2573. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benedek GB. Theory of transparency of the eye. Appl Optics. 1971;10:459–473. doi: 10.1364/AO.10.000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prum RO, Torres RH, Williamson S, Dyck J. Coherent light scattering by blue feather barbs. Nature. 1998;396:28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prum RO, Torres RH. A Fourier tool for the analysis of coherent light scattering by bio-optical nanostructures. Integr Comp Biol. 2003;43(4):591–602. doi: 10.1093/icb/43.4.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noh H, et al. How noniridescent colors are generated by quasi-ordered structures of bird feathers. Adv Mater. 2010. in press; 10.1002/adma.200903699. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Landh T. From entangled membranes to eclectic morphologies: Cubic membranes as subcellular space organizers. FEBS Lett. 1995;369(1):13–17. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00660-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Almsherqi ZA, Kohlwein SD, Deng Y. Cubic membranes: A legend beyond the Flatland of cell membrane organization. J Cell Biol. 2006;173(6):839–844. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borgese N, Francolini M, Snapp E. Endoplasmic reticulum architecture: Structures in flux. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18(4):358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.008. 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadjichristidis N, Pispas S, Floudas G. Block Copolymers: Synthetic Strategies, Physical Properties, and Applications. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. Block copolymer morphology; pp. 346–361. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mezzenga R, et al. Shear rheology of lyotropic liquid crystals: A case study. Liq Cryst. 2005;21(8):3322–3333. doi: 10.1021/la046964b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fontell K. Cubic phases in surfactant and surfactant-like lipid systems. Colloid Polym Sci. 1990;268(3):264–285. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hückstädt H, Göpfert A, Abetz V. Influence of the block sequence on the morphological behavior of ABC triblock copolymers. Polymer. 2000;41(26):9089–9094. http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/30466/description#description. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shefelbine TA, et al. Core-shell gyroid morphology in a poly(isoprene-block-styrene-block-dimethylsiloxane) triblock copolymer. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121(37):8457–8465. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chin J, Coveney PV. Chirality and domain growth in the gyroid mesophase. Proc R Soc Lon Ser A. 2006;462:3575–3600. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maldovan M, Urbas AM, Yufa N, Carter WC, Thomas EL. Photonic properties of bicontinuous cubic microphases. Phys Rev B. 2002;65(16):165123. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martín-Moreno L, García-Vidal FJ, Somoza AM. Self-assembled triply periodic minimal surfaces as molds for photonic band gap materials. Phys Rev Lett. 1999;83(1):73. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finnemore AS, et al. Nanostructured calcite single crystals with gyroid morphologies. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3928–3932. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vukusic P, Sambles J. Shedding light on butterfly wings. P Soc Photo-Opt Inst. 2001;4438:85–95. 10.1117/12.451481. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamley IW, et al. Mechanism of the transition between lamellar and gyroid phases formed by a diblock copolymer in aqueous solution. Langmuir. 2004;20:10785–10790. doi: 10.1021/la0484927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hajduk DA, et al. The gyroid: A new equilibrium morphology in weakly segregated diblock copolymers. Macromolecules. 1994;27:4063–4075. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wohlgemuth M, Yufa N, Hoffman J, Thomas EL. Triply periodic bicontinuous cubic microdomain morphologies by symmetries. Macromolecules. 2001;34(17):6083–6089. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.