Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate (PtdInsP3) mediates intracellular signaling for directional sensing and pseudopod extension at the leading edge of migrating cells during chemotaxis. How this PtdInsP3 signal is translated into remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton is poorly understood. Here, using a proteomics approach, we identified multiple PtdInsP3-binding proteins in Dictyostelium discoideum, including five pleckstrin homology (PH) domain-containing proteins. Two of these, the serine/threonine kinase Akt/protein kinase B and the PH domain-containing protein PhdA, were previously characterized as PtdInsP3-binding proteins. In addition, PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI were identified as previously undescribed PH domain-containing proteins. Specific PtdInsP3 interactions with PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI were confirmed using an in vitro lipid-binding assay. In cells, PhdI associated with the plasma membrane in a manner dependent on both the PH domain and PtdInsP3. Consistent with this finding, PhdI located to the leading edge in migrating cells. In contrast, PhdG was found in the cytosol in WT cells. However, when PtdInsP3 was overproduced in pten− cells, PhdG located to the plasma membrane, suggesting its weak affinity for PtdInsP3. PhdB was found to bind to the plasma membrane via both PtdInsP3-dependent and -independent mechanisms. The PtdInsP3-independent interaction was mediated by the middle domain, independent of the PH domain. In migrating cells, the majority of PhdB was found at the lagging edge. Finally, we deleted the genes encoding PhdB and PhdG and demonstrated that both proteins are required for efficient chemotaxis. Thus, this study advances our understanding of the PtdInsP3-mediated signaling mechanisms that control directed cell migration in chemotaxis.

Keywords: chemotaxis, Dictyostelium, pleckstrin homology domain, PI3 kinase, phosphatase and tensin homolog

Cells sense external chemical gradients and respond by moving toward higher concentrations of chemoattractants. Chemotaxis is important for a variety of physiological events, such as axon guidance, wound healing, and tissue morphogenesis. Recent studies have shown that many components involved in chemotaxis are functionally conserved from human neutrophils to Dictyostelium amoebae (1–3). Chemotaxis requires motility, polarity, and directional sensing. Actin polymerization in pseudopodia at the leading edge of the cell is synchronized with contractile forces generated by myosin motor proteins at the rear of the cell. During chemotaxis, an asymmetrical distribution of cytoskeletal proteins produces the observed elongated cell shape and establishes cell polarity. A directional sensing system biases pseudopodia formation toward the source of chemoattractants, and thus orients cell movement along the gradient.

Several components involved in chemotaxis have been identified through genetic and biochemical studies (4). For example, the seven-transmembrane cAMP receptor 1 (cAR1) binds cAMP and activates a heterotrimeric G-protein. Activation of this G-protein eventually leads to local actin polymerization at the cellular leading edge and drives the extension of pseudopods. However, neither cAR1 nor the receptor-coupled G-protein is enriched in this region because both are distributed uniformly along the plasma membrane (4). In contrast, pleckstrin homology (PH) domain-containing proteins that bind phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate (PtdInsP3), including cytosolic regulator of adenylyl cyclase (CRAC), AKT/protein kinase B (PKB), and PH domain-containing protein A (PhdA) in Dictyostelium as well as PKB/AKT in mammalian neutrophils and fibroblasts (5), are highly localized at the front of chemotaxing cells. These findings suggest that PtdInsP3 locally activates signaling events that lead to actin polymerization at the leading edge. In support of this idea, addition of a membrane-permeable form of PtdInsP3 to fibroblasts and neutrophils triggers the formation of membrane ruffles and increases motility (6).

The production of PtdInsP3 is regulated by PI3K, whereas its dephosphorylation is mediated by phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and SH2 domain-containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP). In Dictyostelium, PI3K is located at the leading edge of cells and phosphorylates PtdIns(4,5)P2 to produce PtdInsP3, whereas PTEN, located at the lagging edge, converts PtdInsP3 to PtdIns(4,5)P2. Both PI3K and PTEN are required for maintaining normal PtdInsP3 levels and chemotaxis toward cAMP (7–9). Cells lacking PTEN display severe defects in PtdInsP3 degradation, leading to PtdInsP3 overproduction in the plasma membrane (8, 10–12) and hyperactivation of the actin cytoskeleton. Therefore, pten− cells extend numerous pseudopodia randomly in every direction and fail to restrict pseudopod extensions to the leading edge of cells (8, 11). Altogether, these observations demonstrate that PTEN regulates the level and localization of PtdInsP3 and restricts chemotactic signaling to the leading edge.

Although previous studies have shown the physiological importance of PtdInsP3-mediated signaling in chemotaxis, molecular links that couple PtdInsP3 to the actin cytoskeleton are largely unknown (13). The identification and characterization of additional proteins that specifically bind PtdInsP3 are critical to furthering our understanding of chemotactic signaling. Numerous proteins contain a potential PtdInsP3-interacting motif, including over 100 PH domain-containing proteins and 8 Dock homology region-1 domain-containing DOCK180 proteins in the Dictyostelium genome. In this study, we used affinity purification and a proteomic approach to identify proteins that bind PtdInsP3.

Results

Identification of PtdInsP3-Binding Proteins.

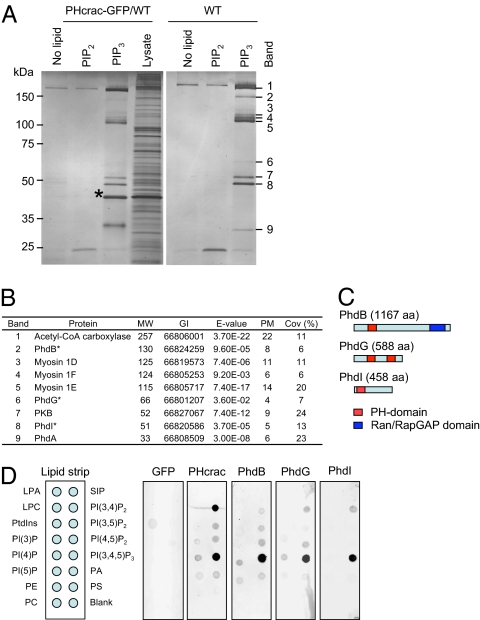

To identify previously undescribed PtdInsP3 interacting proteins, we used affinity purification using PtdInsP3-conjugated beads. After starvation for 3 h, cells were lysed using filter homogenization. High-speed supernatants that contain soluble cytosolic proteins were prepared by ultracentrifugation of the cell lysate. These supernatants then were incubated with beads conjugated to PtdInsP3, and after extensive washing, the bound proteins were eluted and resolved by SDS/PAGE (Fig. 1A). PtdIns(4,5)P2-conjugated and lipid-free beads were used as negative controls. We validated our approach using the PH domain of CRAC (PHcrac), which specifically binds PtdInsP3 in vitro and in vivo (14) (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Identification of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-binding proteins. (A) High-speed supernatants were prepared from WT cells and cells expressing PHcrac-GFP (PHcrac-GFP/WT). Proteins eluted from PtdInsP3-, PtdIns(4,5)P2-, or lipid-free beads were resolved by SDS/PAGE before silver staining. The asterisk indicates PHcrac-GFP. (B) Nine identified proteins. Molecular weight (MW), gene identification number (GI), expected values calculated by the MASCOT program (E-value), numbers of peptide matches (PMs), and coverage of proteins by identified peptides (Cov) are shown. (C) Domain structures of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI were analyzed using Prosite (http://ca.expasy.org/prosite/). (D) Lipid dot blot assays.

We found that nine proteins associate specifically with PtdInsP3 beads in WT cells (Fig. 1A). These proteins were identified by MS (Fig. 1B). Three class I myosin proteins, including myosin 1D (DDB0191347), 1E (DDB0216200), and 1F (DDB0220021), as well as acetyl-CoA carboxylase (DD0230067) were identified. The remaining five were PH domain-containing proteins, including two previously characterized proteins, PH domain-containing protein A (PhdA) and PKB (15, 16), and three previously undescribed proteins that we named PhdB (DDB0216910), PhdG (DDB0184481), and PhdI (DDB0233285). This report focuses on the characterization of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI. The Dictyostelium discoideum genome database predicted PhdB to be a 130-kDa protein with a PH domain at the N terminus and a Ran/RapGAP homology domain at the C terminus (Fig. 1C). Ran GTPases participate in transport into and out of the cell nucleus, whereas Rap GTPases regulate cell adhesion and migration (17, 18). PhdG was predicated to be a 66-kDa protein containing two PH domains with no other known domain, whereas PhdI is a 51-kDa protein containing one PH domain at the N terminus. No transmembrane domain was predicted in any of these proteins.

PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI Bind Specifically to PtdInsP3 in Vitro.

To test further whether PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI bind PtdInsP3, GFP fusion proteins were expressed in D. discoideum, and used in in vitro lipid-binding assays (10, 19). Expression of the fusion proteins was confirmed by Western blot analysis of whole-cell extracts using anti-GFP antibodies. In the lipid-binding assay, supernatants containing the fusion proteins were incubated with nitrocellulose membranes spotted with 15 unique phospholipids (Fig. 1D). Interaction between the fusion protein and lipid was detected using anti-GFP antibodies and fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies. Supernatants containing GFP or PHcrac-GFP, which binds PtdInsP3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 in a similar manner (10), were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Confirming our proteomic data, PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI showed specific interaction with PtdInsP3.

PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI Associate with the Plasma Membrane in Cells.

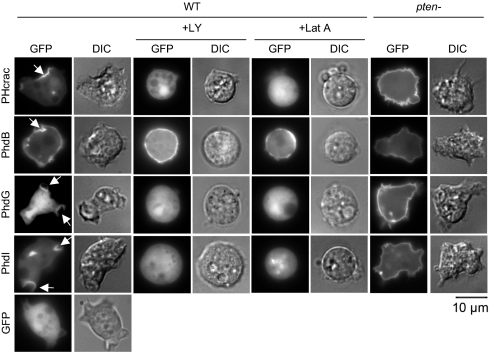

To test whether PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI bind PtdInsP3 in cells, we visualized undifferentiated growing cells expressing the GFP fusion proteins by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2). PHcrac localizes to PtdInsP3-enriched macropinocytic cups and pseudopods on the plasma membrane in undifferentiated growing cells (20). Like PHcrac, PhdI associated preferentially with the PtdInsP3-enriched structures in WT cells (20). In contrast, PhdB was found to associate uniformly with the plasma membrane in addition to the macropinocytic cups and pseudopods. Although PhdG, like PhdB and PhdI, bound PtdInsP3 in the dot blot assay, only a small amount of this protein was associated with the plasma membrane; the majority was found in the cytosol.

Fig. 2.

Localization of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI in undifferentiated growing cells. Localization of PHcrac-GFP, PhdB-GFP, PhdG-GFP, PhdI-GFP, and GFP in undifferentiated WT and pten− cells was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy in the presence or absence of 100 μM LY294002 (+LY) and 5 μM latrunculin A (+Lat A). Arrows indicate macropinocytic cups. (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

To determine whether these proteins bind the plasma membrane via PtdInsP3, we examined the localization of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, which decreases endogenous levels of PtdInsP3 (11) and leads to loss of macropinocytic cups and pseudopods in cells (16). LY294002 treatment resulted in dissociation of PHcrac, PhdG, and PhdI but not PhdB from the plasma membrane (Fig. 2, +LY). These results provide further support for PtdInsP3-mediated association of PhdG and PhdI but not PhdB with the plasma membrane. In addition, the GFP fusion proteins were expressed in pten− cells, which overproduce PtdInsP3 (8). We found dramatically increased amounts of PHcrac, PhdG, and PhdI associated with the plasma membrane (Fig. 2, pten−), suggesting PhdG and PhdI binding to PtdInsP3 in cells. In contrast, the amount of PhdB associated with the plasma membrane did not change in pten− cells, indicating a PtdInsP3-independent mechanism for this association.

When undifferentiated cells were treated with latrunculin A, which disrupts the actin cytoskeleton, cells became round and appeared to lose PtdInsP3 in the plasma membrane, as shown by PHcrac dissociation from the membrane (Fig. 2, +Lat A). Similarly, PhdG and PhdI were lost from the plasma membrane. However, PhdB was still associated uniformly with the plasma membrane in the presence of latrunculin A (Fig. 2). These results suggest that the actin cytoskeleton is required for the membrane interaction of PhdG and PhdI but not PhdB.

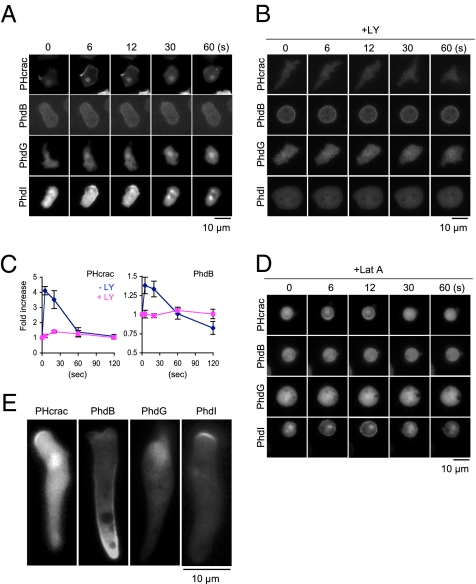

Membrane Association of PhdB and PhdI Is Regulated by cAMP.

In contrast to undifferentiated growing cells, differentiated D. discoideum cells contain lower basal levels of PtdInsP3 and transiently produce PtdInsP3 in the plasma membrane in response to cAMP (21). On uniform cAMP stimulation, the level of PtdInsP3 increases within 5 s and then returns to a basal level in 60 s in WT cells. This transient production of PtdInsP3 recruits PtdInsP3-binding proteins to the plasma membrane and activates downstream effectors in chemotactic signaling (13). To determine whether cAMP stimulation regulates the interaction between PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI with the plasma membrane, we examined their localization after cAMP stimulation using time-lapse fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3A). In these experiments, cells expressing PHcrac, PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI were differentiated and uniformly stimulated with 1 μM cAMP. Similar to PHcrac, PhdB, and PhdI but not PhdG rapidly and transiently translocated from the cytosol to the plasma membrane in response to cAMP. These transient membrane associations were abolished by LY294002 (Fig. 3B). These results clearly demonstrate that PtdInsP3 regulates membrane association of PhdB and PhdI. Because a fraction of PhdB remained associated with the plasma membrane in the presence of LY294002, we further confirmed the PhdB localization using Western blot analysis. Cells expressing PhdB-GFP were lysed after cAMP stimulation in the presence or absence of LY294002 and separated into membrane and soluble fractions. We found that transient membrane association of Phdb-GFP was abolished by LY294002 (Fig. 3C). PHcrac was used as a positive control. Our data indicate that PhdB is associated with the membrane through PtdInsP3-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

Fig. 3.

cAMP regulates the localization of PhdB and PhdI in differentiated cells. Cells expressing PHcrac-, PhdB-, PhdG-, or PhdI-GFP were differentiated for 5 h. Cells were uniformly stimulated with 1 μM cAMP and examined by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy in the absence (−LY) (A) or presence (+LY) of 100 μM LY294002 (B) and 5 μM latrunculin A (Lat A) (D). (C) Quantitation of membrane association of PHcrac-GFP and PhdB-GFP. Cells were stimulated with 1 μM cAMP in the presence or absence of 100 μM LY294002 and lysed at the indicated time points. A membrane fraction was collected by centrifugation (8, 11) and analyzed by Western blot analysis using anti-GFP antibodies. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4). (E) Localization of PHcrac-, PhdB-, PhdG-, and PhdI-GFP in migrating cells. Cells were moving upward in the images. (Scale bars: A–C, E; 10 μm.)

Furthermore, cAMP-stimulated recruitment of PhdI to the plasma membrane is independent of the actin cytoskeleton. We found that PHcrac and PhdI but not PhdB showed a similar time course of localization after cAMP stimulation, regardless of latrunculin A treatment (Fig. 3 A and D).

Localization of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI in Migrating Cells.

Studies have shown that PI3K is activated at the leading edge of migrating cells without external cAMP stimulation, leading to enrichment of PtdInsP3 at the leading edge (22). To determine the localization of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI in migrating cells, we examined cells expressing the respective GFP fusion proteins using fluorescence microscopy after differentiation (Fig. 3E). Control cells expressing PHcrac displayed an elongated polarized shape and contained PtdInsP3 at the leading edge (Fig. 3E). Similarly, PhdI was localized preferentially at the leading edge of migrating cells, consistent with our earlier data that this protein interacts exclusively with the plasma membrane via PtdInsP3 in vivo. In contrast, the majority of PhdB was associated with the lagging edge of cells in the presence or absence of a cAMP gradient (Fig. 3E and Fig. S2). Only a small fraction of PhdB was found at the leading edge. Thus, a PtdInsP3-independent mechanism is critical for the localization of PhdB in migrating cells. PhdG showed no obvious enrichment at the leading or lagging edge (Fig. 3E). Taken together, these results indicate that PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI localization in migrating cells may be controlled by different mechanisms, suggesting that these proteins play distinct roles in cell migration.

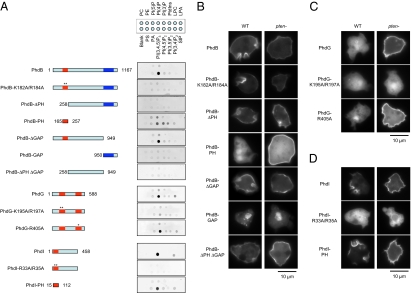

PH Domains Function in Interactions of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI with PtdInsP3 and the Plasma Membrane.

To determine whether PH domains mediate the interactions of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI with PtdInsP3 and the plasma membrane, we mutated the conserved positively charged residues in the second β-strands of the PH domains of these proteins to alanine (Fig. 4 and Fig. S3). These positive residues have been shown to be essential for interactions between PH domains and PtdInsP3 (23). When the R33A/R35A mutation was introduced into PhdI, the protein failed to bind PtdInsP3 and dissociated from the plasma membrane (Fig. 4 A and D). Similar to full-length PhdI, its PH domain also interacted with PtdInsP3 in vitro (Fig. 4A) and with the plasma membrane in a LY294002-sensitive manner in cells (Fig. 4D and Fig. S4A). In differentiated cells, the PH domain of PhdI translocated to the plasma membrane on cAMP stimulation and located to the leading edge of cells undergoing chemotaxis (Fig. S4 B and C). These results demonstrate that the PH domain of PhdI is necessary and sufficient for its interaction with PtdInsP3 both in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Mutational analysis of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI. Point and deletion mutations were introduced into PhdB (A and B), PhdG (A and C), and PhdI (A and D). Asterisks indicate mutations introduced in PH domains. Lipid binding (A) and subcellular localization of mutant proteins in undifferentiated WT and pten− cells (B–D) were examined by dot blot and fluorescence microscopy, respectively.

Mutations in or deletion of the PH domain of PhdB blocks its interaction with PtdInsP3 in vitro (Fig. 4A, PhdB-K182A/R184A and PhdB-ΔPH). The PH domain itself interacted with PtdInsP3 but with reduced specificity (Fig. 4A, PhdB-PH). Therefore, the PH domain is deemed important for interactions between PhdB and PtdInsP3 in vitro. However, PhdB-K182A/R184A and PhdbB-ΔPH normally associate with the plasma membrane in vivo (Fig. 4B). In addition, we found that very little PhdB-PH associated with the plasma membrane in WT cells and that its membrane localization is enhanced in pten− cells (Fig. 4B). In undifferentiated cells, it is likely that the majority of PhdB binds the plasma membrane through a PtdInsP3-independent mechanism, unless PtdInsP3 production is increased. In the PtdInsP3-independent mechanism, the middle region of PhdB, which does not bind to PtdInsP3 in vitro, is sufficient for plasma membrane localization in vivo (Fig. 4 A and B, PhdB-ΔPH ΔGAP). The Ran/RapGAP domain is dispensable for the interaction with both PtdInsP3 and the plasma membrane (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that PhdB has two membrane sites: a strong membrane association that requires the middle domain but not PtdInsP3 and a weak association that depends on both the PH domain and PtdInsP3.

Unlike PhdI and PhdB, PhdG has two PH domains. We found that only the first PH domain is essential for interacting with PtdInsP3, because PhdG (K195A/R197A) but not PhdG (R405A) was unable to interact with PtdInsP3 in both WT and pten− cells (Fig. 4 A and C). When GFP was fused to either the first or second PH domain of PhdG, no expression was detected by fluorescence microscopy or Western blot analysis.

PhdB and PhdG Are Required for Efficient Chemotaxis.

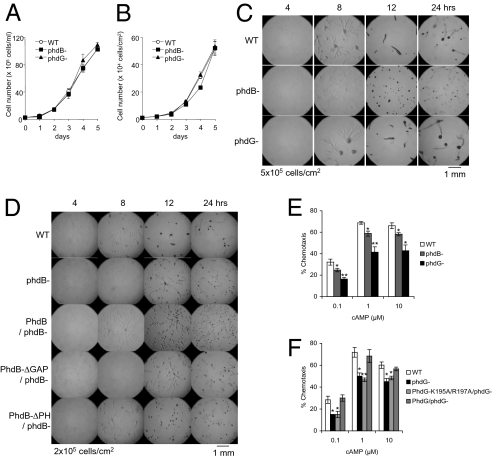

To examine the functions of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI, we deleted the PhdB and PhdG genes by homologous recombination (Fig. S5). We also attempted to delete the PhdI gene but could not obtain phdI− cells. Although both phdB− and phdG− cells grew normally, phdB− cells but not phdG− cells showed a developmental defect after starvation (Fig. 5 A–C). During development, phdB− cells were slow to aggregate and formed smaller fruiting bodies (Fig. 5C). These developmental defects in phdB− cells were rescued by the expression of full-length PhdB (Fig. 5D). Complementation activity requires the Ran/RapGAP domain but not the PH domain, suggesting that the function of PhdB in development is independent of PtdInsP3 signaling (Fig. 5D). Finally, we found that both phdB− and phdG− cells were defective in normal chemotaxis toward cAMP, as demonstrated in small-drop chemotaxis assays (Fig. 5E). The chemotaxis defect in phdG− cells was rescued by the subsequent expression of full-length PhdG but not PhdG-K195A/R197A, demonstrating the functional importance of the PH domain in chemotaxis (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of phdB− and phdG− cells. Cell proliferation in shaking culture (A) and on plastic dishes (B). (C and D) Cells were placed on nonnutrient agar and observed at the indicated time points. (Scale bars: 1 mm.) (E and F) Small-drop chemotaxis assay. All values are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Results were statistically analyzed using t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

Discussion

PtdInsP3 functions as a signaling molecule in many processes, including cell growth, cell migration, and vesicular traffic (24, 25). The production of PtdInsP3 is regulated by PI3K, PTEN, and SHIP in response to different physiological stimuli (26, 27). Several protein motifs have been reported to bind PtdInsP3 (28, 29). One of the largest groups of PtdInsP3-binding proteins is the PH domain-containing proteins. The PH domain consists of a seven-stranded β-sandwich formed from two near-orthogonal β-sheets. There are large numbers of PH domain-containing proteins among different species. For instance, there are ≈300 proteins in humans and 100 proteins in D. discoideum (30, 31). Because 3D structure rather than protein sequence defines the specificity of PH domains, accurately predicting which PH domains specifically bind PtdInsP3 has been difficult (13, 32). Previous studies combining biochemical purification with MS have identified several PtdInsP3-binding proteins (33, 34). However, many additional PtdInsP3-binding proteins remain to be identified. In this report, we used a proteomic approach to identify nine PtdInsP3-binding proteins in D. discoideum, including five PH domain-containing proteins, three myosin I family proteins, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Of these, we characterized three previously undescribed PH domain-containing proteins: PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI.

PhdI binds PtdInsP3 strongly and specifically through its PH domain and is associated with the plasma membrane at the leading edge of migrating cells. Its membrane association is regulated by cAMP in cells. On cAMP stimulation, PhdI transiently interacts with the plasma membrane because of a temporary increase in PtdInsP3 levels. These characteristics implicate PhdI as a signaling molecule that translates changes in PtdInsP3 levels to reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton at the leading edge. Consistent with this potential role, cAMP-stimulated membrane association of PhdI does not require the actin cytoskeleton in differentiated cells, suggesting that PhdI acts upstream of actin remodeling. Homologs of PhdI (e.g., XP_649359, 64387, 001914540, 001914051, 001913509, and 653366) are present in the parasitic amoeba Entamoeba, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role for PhdI in PtdInsP3 signaling.

PhdG, which contains two PH domains, specifically interacts with PtdInsP3 and facilitates efficient chemotaxis toward cAMP. The first PH domain is required for PtdInsP3 binding and normal chemotaxis. In contrast to PhdI, PhdG weakly interacts with the plasma membrane in cells. Very little PhdG-GPF was associated with the plasma membrane, and the majority was present in the cytosol unless PtdInsP3 is overproduced. We speculate that PhdG is involved in chemotaxis when the PtdInsP3 signal is highly activated. For example, PhdG may function in chemotaxis when cells are exposed to higher concentrations of chemoattractants.

Like PhdG, PhdB is also important for chemotaxis and binds to the plasma membrane. Although the PH domain of PhdB mediates its interactions with PtdInsP3, the interaction of PhdB with the plasma membrane is mainly mediated by the middle region, which lacks any obvious membrane-binding motif. Consistent with this, the majority of PhdB associated with the lagging edge of randomly migrating cells as well as chemotaxing cells. Only a small amount of PhdB associated with the leading edge. At the leading edge, PhdB may be involved in PtdInsP3 signaling or may regulate Rap1 activity at the leading edge similar to RapGAP1, which inactivates Rap1 during chemotaxis (35, 36). On the other hand, at the lagging edge, where PTEN, myosin II, and PakA are located, PhdB may function in collaboration with these proteins or regulate them during chemotaxis. For example, PhdB may regulate myosin II through Rap1 at the lagging edge, because Rap1 controls cell motility and adhesion through regulation of myosin II (17). It is also possible that PhdB binds to PtdInsP3 at the rear and sides of chemotaxing cells and is involved in the removal of PtdInsP3 at these locations. Consistent with our findings, a recent study has also shown that PhdB is critical for chemotaxis (18).

Recent studies have described a unique algorithm, the recursive functional classification matrix (RFC) algorithm, to predict PtdInsP3-interacting PH domains (13). Using this algorithm, 15 PH domain-containing proteins were predicted to interact with PtdInsP3 based on their RFC scores. In this study, PhdI and PhdG produced scores of 18.2 and 14.0, respectively, and were thus predicted to bind PtdInsP3. In contrast, PhdB showed a lower score of 6.4 and was not predicted to be a PtdInsP3-binding protein. Our lipid binding analysis showed that PhdG and PhdI, as well as PhdB, interact with PtdInsP3 with equally high specificity. Therefore, the computational predictions for PhdI and PhdG as PtdInsP3-binding proteins were experimentally confirmed by our in vitro data. In addition, these data demonstrated the importance of a biochemical approach for characterizing PtdInsP3 interactions.

Although PtdInsP3 has been shown to play a key role in chemotactic signaling, recent evidence has shown that this is not the only pathway controlling chemotaxis and that PtdInsP3 is dispensable for chemotaxis under several conditions (27, 37). For example, knockout of all five class I PI3K genes in Dictyostelium results in relatively mild chemotactic defects, and the mutant cells still are able to migrate along strong chemoattractant gradients, although with reduced speed (38, 39). In addition, a parallel pathway to PtdInsP3 signaling mediated by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) has been described (11, 40). Although disruption of neither PLA2 nor two class I PI3Ks significantly altered chemotaxis, their combined deletion resulted in a strong defect (11). Thus, chemotactic signaling involves multiple redundant mechanisms. To understand chemotaxis better, it is essential to dissect each pathway at the molecular level and reveal its functional relationships.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture and Differentiation.

WT (Ax2) and pten− (8) D. discoideum cells were axenically cultured in HL5 medium containing 1% proteose peptone (Difco), 0.5% yeast extract (Difco), 1% D-glucose, 2.5 mM Na2HPO4, and 2.5 mM KH2PO4 (pH 6.5) at 22 °C. To induce differentiation of cells, exponentially growing cells were washed twice and resuspended to 2 × 107 cells/mL in development buffer. Cells were starved for 1 h in development buffer and pulsed with 100 nM cAMP at 6-min intervals for 4 h (8).

Lipid-Binding Assay.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared by filter homogenization (8). The extracts were clarified twice by ultracentrifugation to obtain high-speed supernatant fractions. These supernatants were incubated on membranes spotted with different phospholipids (Echelon). After extensive washing, the membranes were probed with anti-GFP antibodies, followed by Cy5-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (816116; Invitrogen). The membranes were scanned by a PharosFX (Bio-Rad) plus molecular imager and analyzed by Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Plasmids.

Full-length and truncated versions of PhdB, PhdG, and PhdI were amplified by PCR using a pair of primers described in Table S1 and then cloned into pIS1, a plasmid that expresses a C-terminal GFP tag from the constitutive actin 15 promoter. Mutations in the PH domains were introduced by overlap extension PCR using primers carrying mutations (41) and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Fluorescence Microscopy.

Images were collected using an Olympus IX70 inverse microscope equipped with 40× and 60× objectives or a Zeiss Axiovert 100 inverted microscope equipped with a 40× objective. SlideBook (3I), IPLab (Scanalytics), QuickTime 7 (Apple, Inc.), Photoshop (Adobe), and Image J (Scanalytics) software programs were used to analyze the images.

Chemotaxis Assay.

The ability of cells to move toward cAMP was examined in small-drop assay, as described (8).

Isolation and Identification of PtdInsP3-Binding Proteins.

Detailed methods for isolation and identification of PtdInsP3-binding proteins are described in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grant 0765345U (to M.I.), National Institutes of Health Grant GM 084015 (to M.I.), American Heart Association Grant 0730247N (to H.S.), and Muscular Dystrophy Association Grant 69361 (to H.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1006153107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Iijima M, Huang YE, Devreotes P. Temporal and spatial regulation of chemotaxis. Dev Cell. 2002;3:469–478. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Haastert PJ, Devreotes PN. Chemotaxis: Signalling the way forward. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:626–634. doi: 10.1038/nrm1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fey P, Kowal AS, Gaudet P, Pilcher KE, Chisholm RL. Protocols for growth and development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1307–1316. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willard SS, Devreotes PN. Signaling pathways mediating chemotaxis in the social amoeba, Dictyostelium discoideum. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung CY, Firtel RA. Signaling pathways at the leading edge of chemotaxing cells. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2002;23:773–779. doi: 10.1023/a:1024479728970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner OD, et al. A PtdInsP(3)- and Rho GTPase-mediated positive feedback loop regulates neutrophil polarity. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:509–513. doi: 10.1038/ncb811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funamoto S, Meili R, Lee S, Parry L, Firtel RA. Spatial and temporal regulation of 3-phosphoinositides by PI 3-kinase and PTEN mediates chemotaxis. Cell. 2002;109:611–623. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iijima M, Devreotes P. Tumor suppressor PTEN mediates sensing of chemoattractant gradients. Cell. 2002;109:599–610. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iijima M, Huang YE, Luo HR, Vazquez F, Devreotes PN. Novel mechanism of PTEN regulation by its phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding motif is critical for chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16606–16613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang YE, et al. Receptor-mediated regulation of PI3Ks confines PI(3,4,5)P3 to the leading edge of chemotaxing cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1913–1922. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, et al. PLA2 and PI3K/PTEN pathways act in parallel to mediate chemotaxis. Dev Cell. 2007;12:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wessels D, Lusche DF, Kuhl S, Heid P, Soll DR. PTEN plays a role in the suppression of lateral pseudopod formation during Dictyostelium motility and chemotaxis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2517–2531. doi: 10.1242/jcs.010876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park WS, et al. Comprehensive identification of PIP3-regulated PH domains from C. elegans to H. sapiens by model prediction and live imaging. Mol Cell. 2008;30:381–392. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parent CA, Blacklock BJ, Froehlich WM, Murphy DB, Devreotes PN. G protein signaling events are activated at the leading edge of chemotactic cells. Cell. 1998;95:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meili R, et al. Chemoattractant-mediated transient activation and membrane localization of Akt/PKB is required for efficient chemotaxis to cAMP in Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 1999;18:2092–2105. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funamoto S, Milan K, Meili R, Firtel RA. Role of phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase and a downstream pleckstrin homology domain-containing protein in controlling chemotaxis in dictyostelium. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:795–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kortholt A, van Haastert PJ. Highlighting the role of Ras and Rap during Dictyostelium chemotaxis. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1415–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeon TJ, Lee S, Weeks G, Firtel RA. Regulation of Dictyostelium morphogenesis by RapGAP3. Dev Biol. 2009;328:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narayan K, Lemmon MA. Determining selectivity of phosphoinositide-binding domains. Methods. 2006;39:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dormann D, Weijer G, Dowler S, Weijer CJ. In vivo analysis of 3-phosphoinositide dynamics during Dictyostelium phagocytosis and chemotaxis. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:6497–6509. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parent CA, Devreotes PN. A cell’s sense of direction. Science. 1999;284:765–770. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki AT, Chun C, Takeda K, Firtel RA. Localized Ras signaling at the leading edge regulates PI3K, cell polarity, and directional cell movement. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:505–518. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemmon MA. Pleckstrin homology domains: Not just for phosphoinositides. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:707–711. doi: 10.1042/BST0320707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czech MP. PIP2 and PIP3: Complex roles at the cell surface. Cell. 2000;100:603–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barber MA, Welch HC. PI3K and RAC signalling in leukocyte and cancer cell migration. Bull Cancer. 2006;93:E44–E52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishio M, et al. Control of cell polarity and motility by the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase SHIP1. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:36–44. doi: 10.1038/ncb1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kölsch V, Charest PG, Firtel RA. The regulation of cell motility and chemotaxis by phospholipid signaling. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:551–559. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balla T, Várnai P. Visualizing cellular phosphoinositide pools with GFP-fused protein-modules. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:pl3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.125.pl3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cozier GE, Carlton J, Bouyoucef D, Cullen PJ. Membrane targeting by pleckstrin homology domains. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2004;282:49–88. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-18805-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiNitto JP, Lambright DG. Membrane and juxtamembrane targeting by PH and PTB domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:850–867. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemmon MA. Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:99–111. doi: 10.1038/nrm2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isakoff SJ, et al. Identification and analysis of PH domain-containing targets of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase using a novel in vivo assay in yeast. EMBO J. 1998;17:5374–5387. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka K, et al. Identification of protein kinase B (PKB) as a phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate binding protein in Dictyostelium discoideum. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999;63:368–372. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krugmann S, et al. Identification of ARAP3, a novel PI3K effector regulating both Arf and Rho GTPases, by selective capture on phosphoinositide affinity matrices. Mol Cell. 2002;9:95–108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeon TJ, Lee DJ, Lee S, Weeks G, Firtel RA. Regulation of Rap1 activity by RapGAP1 controls cell adhesion at the front of chemotaxing cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:833–843. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Rossum DB, et al. Phospholipase Cgamma1 controls surface expression of TRPC3 through an intermolecular PH domain. Nature. 2005;434:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature03340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens L, Milne L, Hawkins P. Moving towards a better understanding of chemotaxis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R485–R494. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrew N, Insall RH. Chemotaxis in shallow gradients is mediated independently of PtdIns 3-kinase by biased choices between random protrusions. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:193–200. doi: 10.1038/ncb1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoeller O, Kay RR. Chemotaxis in the absence of PIP3 gradients. Curr Biol. 2007;17:813–817. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Haastert PJ, Keizer-Gunnink I, Kortholt A. Essential role of PI3-kinase and phospholipase A2 in Dictyostelium discoideum chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:809–816. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higuchi R, Krummel B, Saiki RK. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: Study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7351–7367. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.