Abstract

AIM: To compare the efficacy and safety of acellular dermal matrix (ADM) bioprosthetic material and endorectal advancement flap (ERAF) in treatment of complex anorectal fistula.

METHODS: Ninety consecutive patients with complex anorectal fistulae admitted to Anorectal Surgical Department of First Affiliated Hospital, Xinjiang Medical University from March 2008 to July 2009, were enrolled in this study. Complex anorectal fistula was diagnosed following its clinical, radiographic, or endoscopic diagnostic criteria. Under spinal anesthesia, patients underwent identification and irrigation of the fistula tracts using hydrogen peroxide. ADM was securely sutured at the secondary opening to the primary opening using absorbable suture. Outcomes of ADM and ERAF closure were compared in terms of success rate, fecal incontinence rate, anorectal deformity rate, postoperative pain time, closure time and life quality score. Success was defined as closure of all external openings, absence of drainage without further intervention, and absence of abscess formation. Follow-up examination was performed 2 d, 2, 4, 6, 12 wk, and 5 mo after surgery, respectively.

RESULTS: No patient was lost to follow-up. The overall success rate was 82.22% (37/45) 5.7 mo after surgery. ADM dislodgement occured in 5 patients (11.11%), abscess formation was found in 1 patient, and fistula recurred in 2 patients. Of the 13 patients with recurrent fistula using ERAF, 5 (11.11%) received surgical drainage because of abscess formation. The success rate, postoperative pain time and closure time of ADM were significantly higher than those of ERAF (P < 0.05). However, no difference was observed in fecal incontinence rate and anorectal deformity rate after treatment with ADM and ERAF.

CONCLUSION: Closure of fistula tract opening with ADM is an effective procedure for complex anorectal fistula. ADM should be considered a first line treatment for patients with complex anorectal fistula.

Keywords: Acellular dermal matrix, Surgery, Transsphincteric complex fistula

INTRODUCTION

Anal fistula, an abnormal communication between the anal or rectal lumen and perianal skin, is a common condition in general population, and occurs in 5.6 per 100 000 women and in 12.3 per 100 000 men[1], predominantly in the third and fourth decades of life[2]. It is believed that infection of the intersphincteric glands is the initiating event in anorectal fistula, in a process known as the cryptoglandular hyposis[3]. It is also commonly believed that surgery is the only way to cure it. Up to now, its treatment is diverse due to lack of standard treatment. Incorrect diagnosis and treatment are the important reason of anorectal surgery failure[4]. Traditional surgical procedures include fistulotomy, endorectal advancement flap (ERAF), loose-seton placement, and fibrin glue installation. Anal fistula is described according to the level at which it transgresses the anal sphincter. If the internal opening begins above the anal sphincter, the fistula is described as “high” or transphincteric. Traditional surgery for transsphincteric anal fistula often requires staged operations with fistulotomy and seton insertion. The surgery usually results in large and deep wounds which can take months to heal. Moreover, risk of fecal incontinence is inevitable because part of the anal sphincter is divided during surgery. The success rate of these techniques is disappointed. Fistulotomy invariably requires at least some division of the sphincter muscle with risk of incontinence[4], thus leading to a high recurrence and fecal incontinence. It has been reported that the recurrence rate of ERAF for transsphincteric anal fistula is 0%-63%[5]. Although fibrin glue is an alternative to fistulotomy, its long-term closure rate is low[6-11]. The liquid consistency of fibrin glue is not ideal for closing anorectal fistula, because it is easily extruded from the fistula tract due to the increased pressure[12]. Meta analysis indicates that the healing rate of fibrin glue is not significantly different from that of other sphincter saving procedures for fistula[13]. Complete closure of primary opening and sphincter preserving are the key to successful anorectal fistula surgery. An alternative strategy is to obliterate the fistula tract.

Using a biological substance to close complex anorectal fistula has attracted attention in recent years. A biological anal fistula plug can securely close the primary opening, thus enabling the surgeon to eradicate the fistula tract with a minimal damage to the sphincter. We report our experience with the management of complex anorectal fistulae using acellular dermal matrix (ADM) which is similar to acellular extracellular matrix (AEM). It is a newly developed biomaterial from pigs that have a collagen structure almost identical to that of humans. During manufacturing of the ADM, living cells are removed by special processes to ensure that no transmittable diseases are present in the tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

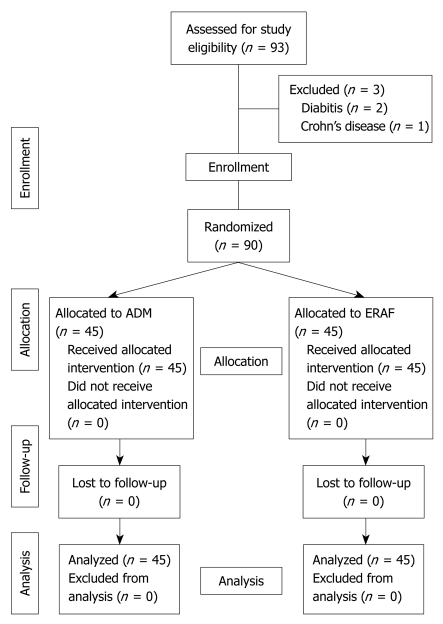

Protocol synopsis for this trial and supporting CONSORT checklist were used as supporting information (Figure 1). ADM trial was a single-center, randomized, prospective, single blinded, controlled trial.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. ADM: Acellular dermal matrix; ERAF: Endorectal advancement flap.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Patients at the age of 12-60 years with 2-6 cm long intrasphincteric and transsphincteric anorectal complex fistulae identified with a fistula probe during surgery, who gave their informed consent, were included in this trial. Patients with no internal opening found during surgery, and those with positive human immunodeficiency virus, Crohn’s disease, malignant cause, tuberculosis, hydradenitis suppurativa, severe cardiovascular state, diabetes, pregnancy, and sepsis were excluded.

Patients

Ninety consecutive patients with complex anorectal fistula, admitted to First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University from March 2008 and July 2009, were randomized into ADM group or ERAF group. Patients were blinded for ADM or ERAF. Demographic data (age and gender of the patients), smoking history, course of disease, fistula types and follow-up time of each patient were recorded (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data about the patients included in this study

| Characteristic | ADM (n = 45) | ERAF (n = 45) | P value |

| Gender (male/female) | 24/21 | 25/20 | NS |

| Age (SD, range) | 18-59 (44.8) | 17-61 (45.1) | NS |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 14 (31) | 11 (24) | NS |

| Course of disease (SD, range, mo) | 3.0-7.1 (4.6) | 2.8-6.9 (5.1) | NS |

| Type of fistula (intrasphincteric/transsphincteric) | 19/26 | 17/28 | NS |

| Median follow-up time | 5.7 (5.1-6.4) | 6.1 (5.9-6.5) | NS |

ADM: Acellular dermal matrix; ERAF: Endorectal advancement flap; NS: Not significant.

Randomization

Randomization was performed during surgery after the internal opening of fistula was identified. Computer-generated random codes were used to produce envelopes containing the information about “ADM” or “ERAF”. These envelopes were prepared by a statistician who was not involved in treatment of patients or in other work specific to the study. Computer randomization was completed at Medical Statistical Center, First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University.

Ethics

The trial, conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and “good clinical practice” guidelines, local regulations, and China government laws, was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University. Prior to the randomization, all patients who gave their informed consent were required to comment on the informed consent before the trial.

Sample size and power

Before the trial, sample size was calculated using SPSS software 13.0 version. Armstrong reported that the success rate of anal fistula plug is 87% for the closure of fistula opening[14] and van der Hagen et al[5] showed that the success rate of ERAF is 37% for the closure of fistula opening, indicating that to increase the success rate from 40% to 80%, at least 44 patients in each group had to be randomized to achieve a power of 90%.

Surgical technique

All patients underwent a proctology at surgery for configuration of the fistula passage. All patients who were given prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics underwent preoperative regular test, endoscopy, anorectal ultrasound and mechanical bowel preparation before surgery. Anesthesia was induced with broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics and 500 mg of intravenous metronidazole. Patients were placed in the prone jackknife position under spinal or general anesthesia. Primary opening was located using a fistula probe or by injecting hydrogen peroxide into the fistula tract. All fistula tracts were irrigated with a hydrogen peroxide solution. A fistula probe was passed through the fistula tract from the secondary opening and pulled out through the primary opening. After the fistula tract was identified and cleaned with curettage and hydrogen peroxide, ADM materials were prepared according to the length and lumen of the fistula tract, inserted into the clean fistula tracts, and pulled into a position using a silk suture passed through the fistula tract and secured to the tip of ADM, then via the secondary opening until it fitted snugly into the primary opening. Excess ADM material was trimmed with the secondary and primary openings flushed and secured to the mucosa and internal sphincter with a 3-0 vicryl suture. All data were recorded and analyzed by the same statistic member who did not attend the intervention.

Rectal advancement flap was done for the control group according to the following techniques. In brief, the primary opening was excised followed by mobilization of the mucosa, submucosa, and a small amount of muscular fibers from the internal sphincter complex. A rectal flap with a 2-3 cm broad base was mobilized. The rectal flap was mobilized sufficiently to cover the internal opening with overlap. Hemostasis was performed to prevent a hematoma under the flap. The fistula tract was curetted. The internal opening was not closed before the flap was advanced over the primary opening. Finally, the flap was sutured to the distal anal canal. All patients were not given analgesics after surgery. Patients were followed up at the discretion of the operating surgeon. Per-operative management (including daily activities, diet) of the two groups was identical.

ADM used in this study was an absorbable J-I type (J. Y. Life Tissue Engineering Co., Ltd., China). It is a complex collagen structure manufactured from the submucosa of porcine small intestine. According to the information about the J-I ADM product, its manufacturing is completely similar to Surgisis AFP™ (Cook Surgical Inc., Bloomington, Indiana, USA). These biologically absorbable xenografts including ADM, AEM, Surgisis or other kinds of anal fistula plug consist of an acellular scaffold similar to the human extracellular matrix[14]. In general, integration into the implant begins within a few days after such materials are placed into the fistula tract through penetrating capillaries.

Postoperative care and follow-up

All patients were hospitalized with a clear liquid diet and bed rest for 48 h. Activity was restricted to minimal. Patients were required to have a warm Sitz bath, 3 times a day. All patients were given intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and metronidazole for 3 d after surgery. Stool softeners were used for 10 d. No activity restriction was requested after discharge. Follow-up examination was performed in the outpatient department 2 d, 2, 4, 6, 12 wk, and 5 mo after surgery, respectively. The primary endpoints of this trial were fistula closure rate. Success was defined as closure of all external openings, absence of drainage without further intervention, and no abscess formation. The presence of one persistent fistula tract was considered surgical failure. Outcomes of ADM and ERAF closure were compared in terms of success rate, fecal incontinence rate, anorectal deformity rate, postoperative pain time, closure time and life quality score.

Continence was evaluated before and after operation using the Wexner score and Vaizey scale. The Vaizey scale consists of 3 items about the type (gas, fluid, solid) and frequency of incontinence (Table 2)[15]. The secondary endpoints were healing time, postoperative pain time, postoperative deformity rate, incontinence rate and quality of life. Patients after operation were asked to grade their pain on a visual analogue scale (VAS: 0 = no pain; 10 = worst imaginable pain) at different time points during the follow-up. Fecal incontinence was evaluated according to the Williams grade. Quality of life was evaluated using the life quality scale system (Table 3)[16].

Table 2.

Vaizey score system

| Never | Rare | Sometimes | Each week | Everyday | |

| Frequency of incontinence | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Solid | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Liquid | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Gas | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Alteration in lifestyle | No | Yes | |||

| Need to wear a pad or plug | 0 | 2 | |||

| Use of constipating medication | 0 | 2 | |||

| Lack of ability to defer defecation for 15 min | 0 | 4 |

Table 3.

Life quality scale system[16]

| Physical |

| P1 It is difficult for me to get out and do things like going to a movie or to church |

| P2 I avoid travelling |

| P3 Whenever I am away from home, I try and stay near a toilet as much as possible |

| P4 I can’t hold on to my bowel motion long enough to get to the bathroom |

| P5 I try to prevent bowel accidents by staying very near a bathroom |

| P6 I cut down on how much I eat before I go out |

| P7 Whenever I go somewhere new, I make sure I know where the toilets are |

| Social |

| S1 I avoid visiting my friends |

| S2 I avoid staying the night away from home |

| S3 It is important to plan my daily activities around my bowel habit |

| S4 I leak stool without even noticing it |

| S5 I can’t do many things I want to do |

| S6 I have sex less often than I would like |

| S7 I feel different from other people |

| S8 I avoid travelling by plane or public transport |

| S9 I avoid going out to eat |

| S10 I am afraid to have sex |

| Emotional |

| E1 I am afraid to go out |

| E2 I worry about not being able to get to the toilet in time |

| E3 I feel unhealthy |

| E4 I feel ashamed |

| E5 I worry about bowel accidents |

| E6 I feel depressed |

| E7 I worry about the smell |

| E8 I enjoy life less |

| E9 The possibility of bowel accidents is always on my mind |

| E10 During the past month have you felt so sad, discouraged, hopeless, or had so many |

| Problems that you wondered whether anything was worthwhile? |

| Overall sense of well-being |

| In general, would you say your health is excellent/very good/good/fair/poor? |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software 13.0 version. Recurrence rate, fecal incontinence rate and anal deformity rate associated with each intervention option were assessed by χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Healing time and postoperative pain time were calculated by Wilcoxon’s test or log rank test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Three patients were excluded from this trial because of diabetes and Crohn’s disease. All patients completed the follow-up during which their data were collected. No patient was lost to follow-up. No significant difference was found in the characteristics of patients including age, sex, classification of fistula and median follow-up time between the two groups. The median follow-up time of ADM and ERAF groups was 5.7 mo (range 5.1-6.4 mo) and 6.1 mo (range 5.9-6.5 mo), respectively (P = 0.12). No severe adverse effect occurred in the patients.

The fistula recurred in 2 (4.45%) and 13 (28.89%) of the 45 patients in the ADM and ERAF groups, respectively (P = 0.0047), and was healed in 37 (82.22%) and 29 (64.44%) of the 45 patients in ADM and ERAF groups, respectively. Early extrusion of ADM occured in 4 patients, and late extrusion in 1 patient. The overall fistula healing rate was 82.22% (37/45) in ADM group. Five and 1 patients received drainage surgery in ERAF and ADM groups, respectively. The life quality score was higher, the fistula healing time and postoperative pain time were shorter in the ADM group than in the ERAF group (P < 0.05, Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7). The recurrence rate of fistula was significantly lower in the ADM group than in the ERAF group. However, no significant difference was observed in incontinence and anal deformity rate between the two groups. In order to clarify the effect of classification on the results, the efficacy and complication rate of intrasphincteric and transsphincteric fistulae were compared (Tables 5 and 6). The recurrence rate of transsphincteric fistula was significantly lower in the ADM group than in the ERAF group. However, no significant difference was observed in the incontinence and anal deformity rate between the two groups.

Table 4.

Recurrence, fecal incontinence, anal deformity, postoperative pain time, and healing time of patients with ADM or ERAF n (%)

| ADM | ERAF | P value | |

| n | 45 | 45 | |

| Recurrence | 2 (4.45) | 13 (28.89) | 0.0047 |

| Fecal incontinence | 1 (2.22) | 4 (8.89) | 0.3574 |

| Anal deformity | 0 (0) | 3 (6.67) | 0.2402 |

| Postoperative pain time (d) | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 7.5 ± 1.8 | 0.0000 |

| Healing time (d) | 7.5 ± 3.5 | 24.5 ± 5.5 | 0.0000 |

Table 5.

Recurrence, fecal incontinence, anal deformity, postoperative pain time, and healing time of patients with intrasphincteric fistula, ADM or ERAF n (%)

| Intra ADM | Intra ERAF | P value | |

| n | 19 | 17 | |

| Recurrence | 0 (0.00) | 3 (17.65) | 0.1907 |

| Fecal incontinence | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Anal deformity | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Postoperative pain time (d) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 1.9 | 0.0000 |

| Healing time (d) | 7.1 ± 3.4 | 24.6 ± 5.4 | 0.0000 |

Table 6.

Recurrence, fecal incontinence, anal deformity, postoperative pain time, and healing time of patients with transsphincteric fistula, ADM or ERAF n (%)

| Trans ADM | Trans ERAF | P value | |

| n | 26 | 28 | |

| Recurrence | 2 (7.69) | 10 (35.71) | 0.0318 |

| Fecal incontinence | 1 (3.85) | 4 (14.29) | 0.9390 |

| Anal deformity | 0 (0.00) | 3 (10.71) | 0.2615 |

| Postoperative pain time (d) | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 8.6 ± 1.4 | 0.0000 |

| Healing time (d) | 7.6 ± 3.6 | 25.9 ± 5.7 | 0.0000 |

Table 7.

Life quality score in different groups

| Group | n | Life quality score | P value |

| ADM | 45 | 85.9 ± 5.3 | |

| Intra ADM | 19 | 87.6 ± 6.5 | |

| Trans ADM | 26 | 83.5 ± 5.7 | |

| ERAF | 45 | 65.3 ± 8.9 | 0.0000 |

| Intra ERAF | 17 | 64.3 ± 5.1 | 0.00001 |

| Trans ERAF | 28 | 65.9 ± 7.8 | 0.00002 |

Represents comparison between intrasphincteric fistulae using ADM and ERAF;

Represents comparison between transsphincteric fistulae using ADM and ERAF.

DISCUSSION

Surgery is considered the predominant and only procedure for anorectal fistula. Although fistulotomy is a simple procedure for fistula, it is not indicated for transsphincteric fistulae because of prohibitive risk of incontinence. Seton cutting, which can slowly divide the sphincter and prevent recurrent abscess formation, is considered a more efficient procedure for trassphincteric fistula, but can cause incontinence of solid stool in up to 25% of patients[17]. ERAF has become a treatment of choice for most fistulae. However, recent reports suggest that the recurrence rate of fistula is 36%-45% after ERAF[5,18,19]. ERAF is also technically difficult, and carries a risk of rectal bleeding and incontinence. In our study, hemorrhage occurred in 2 (4.44%) and incontinence occurred in 4 (14.29%) patients in the ERAF group, which are lower than the reported findings[20]. Over the last few years, fibrin glue has been widely described as a better treatment of choice with no side effects, such as pain and incontinence[6,7,9,12,21,22]. However, it was reported that the healing rate of fistula is 78% and 40%-54%, respectively, after the use of fibrin glue[7,23,24], which is not improved even after antibiotics are added or mucosal advancement flap is supplemented[25].

Continence and healing are the two treatment goals to be achieved, but they often conflict with each other. Another sphincter-preserving surgical method is to use bioabsorbable material for anal fistula, which was first reported by Johnson et al[14] in 2006 with a success rate of 87%, and O'Connor et al[26] reported that the short-term success rate of bioabsorbable material is 80% for anal fistula, indicating that bioabsorbable material can be used in treatment of fistula due to its inherent resistance to infection. Placement of ADM, a minimally invasive procedure for fistula, is an attractive treatment of choice for fistula. Pocrine ADM is a regenerative tissue matrix isolated from decellularized intestines. Similar to Surgisis or other prosthetic meshes, ADM has also been shown to resist infection[27,28]. In our study, the short-term success rate of ADM was 82.22% (37/45) for complex anorectal fistula, which is consistent with the reported findings[26]. In order to compare and evaluate its efficacy, we searched most of the original effects of bioabsorbable material on anorectal fistula across the world (Table 8). Christoforidis et al[36] and Ky et al[40] showed that the success rate of biologically absorbable substance for complex anorectal fistulas is lower than that reported by Song et al[39].

Table 8.

Publications on anal fistula plug in the World

| Author | Publication form | Total patients (n) | Crohn’s patients (n) | Follow-up median (mo) | Success rate (%) |

| Adamina et al[29], 2010 | Article | 12 | 0 | 12.6 (10-14) | 50.0 |

| Schwandner et al[30], 2009 | Article | 60 | 0 | 12 | 62.0 |

| Schwandner et al[31], 2009 | Article | 36 | 0 | 9 | 75.0 |

| Zubaidi et al[32], 2009 | Article | 23 | 0 | 12 | 83.0 |

| Ortiz et al[33], 2009 | Article | 15 | 0 | 12 | 20.0 |

| Chung W et al[34], 2009 | Article | 65 | 0 | 12 | 59.3 |

| Wang et al[35], 2009 | Article | 29 | 0 | 18 (9.1-26.8) | 34.0 |

| Christoforidis et al[36], 2009 | Article | 37 | 4 | 14 (6-22) | 32.0 |

| Safar et al[37], 2009 | Article | 35 | 4 | 4 | 14.0 |

| Christoforidis et al[38], 2008 | Article | 49 | 4 | 6.5 | 43.0 |

| Song et al[39], 2008 | Article | 30 | 0 | 6.3 | 100.0 |

| Ky et al[40], 2008 | Article | 45 | 14 | 6.5 (3-13) | 84.0 |

| Lawes et al[41], 2008 | Article | 20 | 0 | 7.4 | 24.0 |

| Ellis[42], 2007 | Article | 17 | 5 | 6 | 88.0 |

| van Koperen et al[43], 2007 | Article | 17 | 1 | 7 | 41.0 |

| Ky et al[44], 2007 | Abstract | 37 | 8 | 3 | 84.0 |

| Abbas et al[45], 2007 | Abstract | 17 | 0 | 7.4 | 24.0 |

| Bohe et al[46], 2007 | Abstract | 32 | 7 | 6 | 65.0 |

| Lenisa et al[47], 2007 | Abstract | 27 | 0 | 11 | 63.0 |

| Thekkinkattil et al[48], 2007 | Abstract | 40 | 0 | 6 | 40.0 |

| Poirier et al[49], 2006 | Abstract | 27 | 0 | 5 | 59.0 |

| Champagne et al[50], 2006 | Article | 46 | 0 | 12 | 83.0 |

The possible reason why our success rate was much lower than the reported findings[39] is that all the procedures were performed by 4 surgeons. Another possible explanation for this difference may be the selection bias of patients. Contrary to our results, however, Zubaidi et al[32] found that trassphincteric fistula is more likely to heal after plug placement. Ky et al[40] and Ellis[42] have reported a high success rate of plug placement for trassphincteric fistula. We focused on fistula channel debridement and complete drainage during surgery in order to prevent abscess formation as previously described[31]. Because more granulation tissues in the fistula tract can function as a barrier to cellular infiltration into ADM, it is difficult to imagine that simple irrigation with hydrogen peroxide without thorough curettage of the tract can clean the tract and allow incorporation of ADM material into its surroundings. We believe that the low success rate in the study by Safar et al[37] is due to inadequate debridement and curettage of granulation tissue. Complete debridement, curettage of the tract, and hydrogen peroxide irrigation may be important for the surgery to achieve a greater success rate. This point differs from that of Schwandner et al[31]. In our study, 5 patients (11.11%) experienced ADM dislodgement, which may be due to the poor ADM fixation to the sphincter in the primary opening. Technical failure associated with plug-falling out is an important reason for surgery failure[31].

In our study, the success rate of ADM for complex fistula was 82.22% (37/45), indicating that placement of ADM is a safe, beneficial, minimally invasive procedure for fistula, and can protect the anal function.

Lawes et al[41] proposed to combine anal fistula plug and advancement flap for fistula. However, we hold that selection of patients, complete debridement, tract preparation and plug fixation are closely associated with the final success rate.

It is essential to use antibiotics before surgery. It was reported that anorectal abscess is not formed in patients after treatment with AEM[39] or Surgisis[50]. However, early infection occurred in our study. Although use of Surgisis is not associated with perianal sepsis[14], it has been shown that the incidence of severe perianal sepsis is 23%[41]. Although the sepsis rate of ADM (1/45) was significantly lower than that of ERAF (5/45) in our study, more evidence is needed for the evaluation of ADM. Safar et al[37] suggested that the success rate of plug for fistula is not associated with the preoperative bowel preparation, but we performed mechanical bowel preparation before surgery to avoid possible constipation or infection after surgery.

In our study, ADM could obviously shorten the postoperative pain time and the fistula healing time, but not the deformity and incontinence rate of transsphincteric fistula. Transsphincteric fistula recurred in 2 patients, suggesting that it is necessary to perform multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficiency of ADM on transsphincteric complex fistula.

A significant number of patients in ERAF group in this study had long-term continence disturbances in forms of gas and liquid stool incontinence, which may be associated with ERAF or fistulotomy, abscess drainage, and other anorectal treatment modalities.

An adequate follow-up time is essential in a comparative study of ADM and ERAF for complex fistula. Only one study is available with a long follow-up time[33]. The follow-up time in our study is similar to that in previous studies[42,43,46]. The success rate of ADM for fistula (82.22%) was associated with the ADM itself and the adequate follow-up time in our study. Zubaidi et al[32] showed that a longer follow-up time and over an 80% success rate of biologically absorbable substance for fistula provide better evidence for the use of ADM. Song et al [39] reported convincing results based on 6.3 mo follow-up time. However, Wang et al[35] showed that the success rate of biologically absorbable substance for fistula is only 34% after a follow-up time of 18 mo.

In conclusion, closure of the fistula tract primary opening using ADM is an effective and acceptable procedure for complex anorectal fistula. ADM is a a safe, beneficial, minimally invasive procedure for fistula, and can protect anal function. ADM dislodgement is associated with the closure techniques. Further longer-term multicenter randomized controlled clinical trials are needed to evaluate its efficacy on complex anorectal fistula.

COMMENTS

Background

Anal fistula is an abnormal chronic communication between the anal or rectal lumen and perianal skin. Surgery usually results in large and deep wounds which can take months to heal. Moreover, risk of fecal incontinence is inevitable because part of the anal sphincter is divided during surgery. The success rate of different techniques is disappointed. Using a biological substance to close complex anorectal fistula is attractive.

Research frontiers

Acellular dermal matrix (ADM) is a bioabsorbable xenograft for tissue defect. Application of different kinds of ADM in treatment of anorectal fistula is a hotspot in the World.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Closure of the fistula tract primary opening using ADM is an effective and acceptable alternative to complex anorectal fistula. ADM is a safe, beneficial, minimally invasive procedure for fistula, and can protect anal function. It should be considered a first line treatment for patients with complex anorectal fistula.

Applications

This method can reduce postoperative pain, shorten fistula healing time, and improve the postoperative life quality of patients.

Peer review

This is an interesting and generally well written paper with the effects of endorectal mucosal advancement flap and acellular dermis plug on complex fistula compared. The results are striking.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Wei-Li Yan, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Xinjiang Medical University, for her help and excellent technical and methodological support to this randomized trial.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Marc Basson, MD, PhD, MBA, Department of Surgery, Michigan State University, 1200 East Michigan Avenue, Suite #655, Lansing, MI 48912, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Sainio P. Fistula-in-ano in a defined population. Incidence and epidemiological aspects. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1984;73:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks CG, Ritchie JK. Anal fistulas at St Mark's Hospital. Br J Surg. 1977;64:84–91. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800640203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parks AG. Pathogenesis and treatment of fistuila-in-ano. Br Med J. 1961;1:463–469. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5224.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamadani A, Haigh PI, Liu IL, Abbas MA. Who is at risk for developing chronic anal fistula or recurrent anal sepsis after initial perianal abscess? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:217–221. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819a5c52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Hagen SJ, Baeten CG, Soeters PB, van Gemert WG. Long-term outcome following mucosal advancement flap for high perianal fistulas and fistulotomy for low perianal fistulas: recurrent perianal fistulas: failure of treatment or recurrent patient disease? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:784–790. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchanan GN, Bartram CI, Phillips RK, Gould SW, Halligan S, Rockall TA, Sibbons P, Cohen RG. Efficacy of fibrin sealant in the management of complex anal fistula: a prospective trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1167–1174. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6708-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis CN, Clark S. Fibrin glue as an adjunct to flap repair of anal fistulas: a randomized, controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1736–1740. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0718-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sentovich SM. Fibrin glue for all anal fistulas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:158–161. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sentovich SM. Fibrin glue for anal fistulas: long-term results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:498–502. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6589-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JG, Farrands PA, Williams AB, Taylor BA, Lunniss PJ, Sagar PM, Varma JS, George BD. The treatment of anal fistula: ACPGBI position statement. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9 Suppl 4:18–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisbertz SS, Sosef MN, Festen S, Gerhards MF. Treatment of fistulas in ano with fibrin glue. Dig Surg. 2005;22:91–94. doi: 10.1159/000085299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammond TM, Grahn MF, Lunniss PJ. Fibrin glue in the management of anal fistulae. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:308–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cirocchi R, Farinella E, La Mura F, Cattorini L, Rossetti B, Milani D, Ricci P, Covarelli P, Coccetta M, Noya G, et al. Fibrin glue in the treatment of anal fistula: a systematic review. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2009;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson EK, Gaw JU, Armstrong DN. Efficacy of anal fistula plug vs. fibrin glue in closure of anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:371–376. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, Kane RL, Mavrantonis C, Thorson AG, Wexner SD, Bliss D, Lowry AC. Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:9–16; discussion 16-17. doi: 10.1007/BF02237236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Aguilar J, Belmonte C, Wong DW, Goldberg SM, Madoff RD. Cutting seton versus two-stage seton fistulotomy in the surgical management of high anal fistula. Br J Surg. 1998;85:243–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.02877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubsky PC, Stift A, Friedl J, Teleky B, Herbst F. Endorectal advancement flaps in the treatment of high anal fistula of cryptoglandular origin: full-thickness vs. mucosal-rectum flaps. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:852–857. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Koperen PJ, Wind J, Bemelman WA, Bakx R, Reitsma JB, Slors JF. Long-term functional outcome and risk factors for recurrence after surgical treatment for low and high perianal fistulas of cryptoglandular origin. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1475–1481. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schouten WR, Zimmerman DD, Briel JW. Transanal advancement flap repair of transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1419–1422; discussion 1422-1423. doi: 10.1007/BF02235039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zmora O, Mizrahi N, Rotholtz N, Pikarsky AJ, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Fibrin glue sealing in the treatment of perineal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:584–589. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cintron JR, Park JJ, Orsay CP, Pearl RK, Nelson RL, Abcarian H. Repair of fistulas-in-ano using autologous fibrin tissue adhesive. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:607–613. doi: 10.1007/BF02234135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maralcan G, Başkonuş I, Aybasti N, Gökalp A. The use of fibrin glue in the treatment of fistula-in-ano: a prospective study. Surg Today. 2006;36:166–170. doi: 10.1007/s00595-005-3121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Koperen PJ, Wind J, Bemelman WA, Slors JF. Fibrin glue and transanal rectal advancement flap for high transsphincteric perianal fistulas; is there any advantage? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:697–701. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0460-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singer M, Cintron J, Nelson R, Orsay C, Bastawrous A, Pearl R, Sone J, Abcarian H. Treatment of fistulas-in-ano with fibrin sealant in combination with intra-adhesive antibiotics and/or surgical closure of the internal fistula opening. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:799–808. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0898-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connor L, Champagne BJ, Ferguson MA, Orangio GR, Schertzer ME, Armstrong DN. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of Crohn's anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1569–1573. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0695-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buinewicz B, Rosen B. Acellular cadaveric dermis (AlloDerm): a new alternative for abdominal hernia repair. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52:188–194. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000100895.41198.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holton LH 3rd, Chung T, Silverman RP, Haerian H, Goldberg NH, Burrows WM, Gobin A, Butler CE. Comparison of acellular dermal matrix and synthetic mesh for lateral chest wall reconstruction in a rabbit model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1238–1246. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000254347.36092.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adamina M, Hoch JS, Burnstein MJ. To plug or not to plug: a cost-effectiveness analysis for complex anal fistula. Surgery. 2010;147:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwandner T, Roblick MH, Kierer W, Brom A, Padberg W, Hirschburger M. Surgical treatment of complex anal fistulas with the anal fistula plug: a prospective, multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1578–1583. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a8fbb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwandner O, Fuerst A. Preliminary results on efficacy in closure of transsphincteric and rectovaginal fistulas associated with Crohn's disease using new biomaterials. Surg Innov. 2009;16:162–168. doi: 10.1177/1553350609338041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zubaidi A, Al-Obeed O. Anal fistula plug in high fistula-in-ano: an early Saudi experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1584–1588. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a90b65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ortiz H, Marzo J, Ciga MA, Oteiza F, Armendáriz P, de Miguel M. Randomized clinical trial of anal fistula plug versus endorectal advancement flap for the treatment of high cryptoglandular fistula in ano. Br J Surg. 2009;96:608–612. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung W, Kazemi P, Ko D, Sun C, Brown CJ, Raval M, Phang T. Anal fistula plug and fibrin glue versus conventional treatment in repair of complex anal fistulas. Am J Surg. 2009;197:604–608. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang JY, Garcia-Aguilar J, Sternberg JA, Abel ME, Varma MG. Treatment of transsphincteric anal fistulas: are fistula plugs an acceptable alternative? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:692–697. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819d473f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christoforidis D, Pieh MC, Madoff RD, Mellgren AF. Treatment of transsphincteric anal fistulas by endorectal advancement flap or collagen fistula plug: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:18–22. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819756ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Safar B, Jobanputra S, Sands D, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Anal fistula plug: initial experience and outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:248–252. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819c96ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christoforidis D, Etzioni DA, Goldberg SM, Madoff RD, Mellgren A. Treatment of complex anal fistulas with the collagen fistula plug. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1482–1487. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song WL, Wang ZJ, Zheng Y, Yang XQ, Peng YP. An anorectal fistula treatment with acellular extracellular matrix: a new technique. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4791–4794. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ky AJ, Sylla P, Steinhagen R, Steinhagen E, Khaitov S, Ly EK. Collagen fistula plug for the treatment of anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:838–843. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawes DA, Efron JE, Abbas M, Heppell J, Young-Fadok TM. Early experience with the bioabsorbable anal fistula plug. World J Surg. 2008;32:1157–1159. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9504-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellis CN. Bioprosthetic plugs for complex anal fistulas: an early experience. J Surg Educ. 2007;64:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Koperen PJ, D'Hoore A, Wolthuis AM, Bemelman WA, Slors JF. Anal fistula plug for closure of difficult anorectal fistula: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2168–2172. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-0298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ky A, Sylla P, Kim S, Steinhagen R. Short-term results in the treatment of anal fistulas with Surgisis® AFP. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:725. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abbas M, Lawes D, Tejirian T, Hamadani A, Heppell J. Young-Fadok T. Anal fistula plug (AFP™) for the treatment of fistula in ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:749. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bohe M, Stark M, Zawadzki A. The results of the anal fistula plug for high transsphincteric fistula. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lenisa L, Rusconi A, Mascheroni L, Andreoli M, Grignani R, Mégevand J. Obliterative treatment for cryptoglandular fistula with anal plug. Does it work in Europe? Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:54. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thekkinkattil D, Gonsalves S, Burke D. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of recurrent anorectal fistulae. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:59. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poirier M, Citron J, Nelson R, Prasad L, Abcarian H. Surgisis AFP: a changing paradigm in the treatment of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:770. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Champagne BJ, O'Connor LM, Ferguson M, Orangio GR, Schertzer ME, Armstrong DN. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1817–1821. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0755-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]