Abstract

Background

Collateral flow to the infarct artery territory after acute myocardial infarction may be associated with improved clinical outcomes and may also influence impact the benefit of subsequent recanalization of an occluded infarct-related artery.

Methods and Results

To understand the association between baseline collateral flow to the infarct territory on clinical outcomes and its interaction with PCI of an occluded infarct artery, long-term outcomes in 2173 patients with total occlusion of the infarct artery 3 to 28 days after myocardial infarction, from the OAT randomized trial were analyzed according to angiographic collaterals documented at study entry. There were important differences in baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics as a function of collateral grade, with generally lower risk characteristics associated with higher collateral grade. Higher collateral grade was associated with lower rates of death (p=0.009), class III and IV heart failure (p<0.0001) or either (p=0.0002), but had no association with the risk of reinfarction. However, by multivariate analysis, collateral flow was neither an independent predictor of death, nor of the primary endpoint of the trial (composite of death, reinfarction or class IV heart failure). There was no interaction between angiographic collateral grade and the results of randomized treatment assignment (PCI or medical therapy alone) on clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

In recent myocardial infarction, angiographic collaterals to the occluded infarct artery are correlates but not independent predictors of major clinical outcomes. Late recanalization of the infarct artery in addition to medical therapy shows no benefit compared to medical therapy alone, regardless of the presence or absence of collaterals. Therefore, revascularisation decisions in patients with recent myocardial infarction should not be based on the presence or grade of angiographic collaterals.

Keywords: collaterals, heart failure, myocardial infarction, recanalization

Angiographically visible coronary collaterals in humans have been postulated to exert a beneficial effect on infarct size1, ventricular aneurysm formation2,3, viability and ventricular function following acute coronary occlusion 3-5. In acute myocardial infarction (MI) treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), however, there have been conflicting reports regarding this postulated link and observed clinical outcomes 6, 7.

The randomized Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) tested routine percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for persistently occluded infarct-related coronary arteries 3 to 28 days post-MI. It afforded an opportunity to examine the relationship between visible collateralisation of the infarct-related artery and long-term outcome in a large, rigorously characterized cohort of MI survivors8. Specifically, OAT mandated centrally analyzed coronary angiography at baseline (median 8 days from infarction to randomization) that included semi-quantitative assessment of ipsilateral and contralateral collateral flow in both study arms (PCI or optimal medical therapy alone) 9 Long-term adjudicated outcomes were then collected.

As in acute MI, the degree of visible collateral flow during both sub-acute and chronic post MI phases has the potential to influence late clinical outcome through preserved viability, altered ventricular geometry or electrical substrate. Moreover, it is conceivable that the degree of collateralization modulates the influence of late infarct artery recanalization. This interaction might operate by preserving viability such that PCI both relieves ischemia and enables regional LV recovery. 10 Alternatively, late recanalization of persistently occluded infarct arteries might be most beneficial in patients without the robust collateral flow implied by easily observed collateralization. to the infarct artery territory11 In the present analysis, we sought to assess the association between baseline collaterals and overall clinical outcomes, and to explore a potential interaction between collaterals and PCI versus medical therapy alone.

Methods

The methods used in OAT have been described in detail previously 9. In brief, 2201 patients were enrolled (2166 between February 2000 and December 2005 in the main OAT study, and 35 patients in the extension phase of OAT-NUC substudy in 2006) and observed for a mean of 3.2 years. By 5 years, 30% either had reached a primary outcome or were still being followed. Patients were eligible for enrollment if coronary angiography, performed on calendar days 3 to 28 (minimum 24 hours) after myocardial infarction, showed total occlusion of the infarct-related artery with poor or absent antegrade flow (TIMI-flow grade of 0 or 1), and if they met a criterion for increased risk (left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) ≤50%, proximal occlusion of a major epicardial vessel, or both). Patients were excluded from the study if they had New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV heart failure, shock, serum creatinine ≥2.5 mg/dL (221 μmol/ liter), angiographically significant left main or three-vessel coronary artery disease, angina at rest, or severe ischemia on stress testing. Patients were randomly assigned to PCI with stent placement and optimal medical therapy (PCI group) or optimal medical therapy alone (MED group). Images from the baseline angiogram collected in both groups were reviewed (by an angiography core laboratory blinded to treatment assignment), and collaterals were graded in 3 categories according to a modified TIMI phase I collateral score 12 whereby in grade 0, there is no angiographic filling of the distal vessel, in grade 1, there is faint opacification of the distal vessel only or only small segments are visualized and in grade 2, the entire distal vessel is visualized and densely opacified. In the case of several pathways per lesion, the largest one was considered for further analysis. The primary endpoint of OAT (and therefore used in this secondary analysis) was a composite of death from any cause, reinfarction, and hospitalization for NYHA IV HF. Study sites submitted clinical records pertaining to all hospitalizations for cardiovascular events and pneumonia for review to avoid ascertainment bias. Whether HF was responsible for these hospitalizations was centrally confirmed according to pre-specified criteria and NYHA class at the time of hospitalization was determined by an independent event committee whose members were blinded to treatment assignment. The specific process of central adjudication of HF events has been previously described9. For this report, centrally confirmed hospitalizations for both NYHA Class III and NYHA Class IV HF are reported. Mortality events and their cause were centrally reviewed.

Secondary endpoints included each component of the primary endpoint, class III or IV heart failure as well as composites of each component with death. The prespecified definition of reinfarction required two of the following three criteria: symptoms for 30 or more minutes, electrocardiographic changes, and elevated cardiac markers.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes were studied in groups of patients divided as a function of baseline angiographic collaterals using conventionally defined collateral flow grade describing only the most robust collateral supply. These analyses were done in a binary fashion (i.e. comparing patients without collaterals to patients with grade I or II collaterals) as well as by analyzing the best observed collateral flow by semi-quantitative grade. The analyses were then repeated after applying a novel ‘total flow ’ score in which all sources of residual flow to the distal infarct-related artery were summed (total flow = sum of collateral grades [0-2] from all non-IRA sources + residual TIMI flow grade in IRA). In a second step, outcomes were analyzed as a function of initial randomization (i.e. PCI and optimal medical therapy vs optimal medical therapy alone), with analyses for interactions.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of study patients were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as the means with standard deviation for continuous variables and compared within the collateral grade category with Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for trend or ANOVA respectively. (The Mantel-Haenszel chi-square statistic tests the alternative hypothesis that there is a linear association between the row variable and the column variable.) Kaplan-Meier curves for patients within collateral grade levels were compared with log-rank tests. Interaction between study assigned treatment and the collateral grade was assessed with use of a Cox regression model.

The degree of collaterals was modeled as an indicator variable with the hazard ratio for the estimate of the 5-year primary and secondary outcomes in patients with grade=0 collaterals compared to that of patients with grade 1 or 2 collaterals. Analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. The variables were chosen by cox models using backward elimination with p<=0.01 to remain in the model. All 37 standard baseline variables were considered for these models. The methods are similar to those used in Kruk et al 12

To reduce the likelihood of type I errors, the OAT protocol required that all secondary analyses employ a p-value threshold of ≤0.01 9. SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Core laboratory data describing collateral flow to the infarct artery territory was available for 1087 and 1086 (99% of all randomized patients) of the patients randomly assigned to PCI or to MED, respectively. The distribution of angiographic collaterals at baseline was similar between the two arms: 251 patients [134 (12.3%) PCI and 117 (10.8%) MED] had no visible collaterals, while 1922 patients had grade I [778 (71.6%) PCI and 770 (70.9%) MED] or II [175 (16.1%) PCI and 199 (18.3%) MED] collateral support to the occluded infarct-related artery. The baseline and angiographic characteristics of the patients according to collateral grade are described in Table 1. Overall, patients with better collateral flow grades were more likely to have characteristics suggesting lower baseline risk including younger age, freedom from prior diabetes or heart failure, lower heart rate, lower fasting glucose, higher left ventricular ejection fraction, a culprit artery other than the left anterior descending artery. Well developed collaterals were also associated with a longer interval from symptom onset to diagnostic coronary angiography (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical and Angiographic Characteristics According to Collateral Grade

| Grade 0 (n=251) |

Grade 1 (n=1548) |

Grade 2 (n=374) |

P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Mean age, y | 60.4±10.7 | 58.5±11 | 57.9±10.6 | 0.01 |

| Men | 80 | 78 | 74 | 0.07 |

| Caucasian | 74 | 80 | 82 | 0.02 |

| History of diabetes | 30 | 20 | 14 | <0.0001 |

| History of angina | 21 | 22 | 24 | 0.36 |

| History of MI | 14 | 10 | 13 | 0.88 |

| Hypertension | 57 | 49 | 44 | 0.002 |

| History of cerebrovascular disease | 4.4 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 0.24 |

| History of PAD | 4.4 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 0.37 |

| Renal insufficiency | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.56 |

| History of congestive heart failure | 4.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0.19 |

| History of percutaneous coronary intervention |

4.4 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 0.56 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 52 | 52 | 50 | 0.56 |

| Family history of CAD | 38 | 40 | 44 | 0.11 |

| Killip class > I during index MI | 27 | 18 | 17 | 0.006 |

| Current smoker | 36 | 39 | 44 | 0.03 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 75±13 | 72±12 | 69±11 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 123±20 | 120±17 | 122±19 | 0.02 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 73±12 | 72±11 | 72±12 | 0.65 |

| Estimated GFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 80±25 | 80±22 | 82±19 | 0.25 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 128±41 | 120±43 | 112±37 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29±5.9 | 28.6±5 | 27.7±4.5 | 0.003 |

| Index event | ||||

| S3 gallop | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.2 |

| Rales | 14 | 5.7 | 4.0 | <0.0001 |

| New Q waves | 69 | 67 | 65 | 0.37 |

| ST elevation | 77 | 68 | 52 | <0.0001 |

| R loss | 47 | 45 | 34 | 0.0005 |

| Thrombolytic treatment in first 24 h | 25 | 19 | 16 | 0.009 |

| Time since MI, days | 9.7±7.4 | 11.1±7.7 | 11.5±7.5 | 0.01 |

| Angiographic data | ||||

| Culprit artery: LAD | 49 | 40 | 11 | <0.0001 |

| Multivessel disease | 23 | 17 | 17 | 0.07 |

| Ejection fraction | 45±12 | 47±11 | 51±10 | <0.0001 |

BP indicates blood pressure; CAD, coronary artery disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LAD, lateral anterior descending; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Values are reported as % for binary variables and as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables.

Mantel-Haenszel χ2 trend

Collaterals and the primary endpoint

Cumulative 60-month lifetable estimated event rates according to the presence or absence of collaterals are summarized in Table 2, and the relation between angiographic collateral flow grade and clinical outcomes at 60 months is depicted in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Cumulative 60-Month Lifetable Estimated Event Rates According to Presence or Absence of Collaterals

| Event | No collaterals (n=251) |

Any collaterals (n=1922) |

P | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome (death, MI, CHF class IV) |

All patients (%) | 22.7 | 16.9 | 0.014 | |

| PCI | 28 (25.4) | 135 (18.0) | |||

| MED | 21 (18.7) | 124 (15.9) | 0.89 | ||

| Death | All patients | 15.4 | 11.3 | 0.16 | |

| PCI | 17 (16.1) | 74 (11.1) | |||

| MED | 11 (14.8) | 81 (11.5) | 0.44 | ||

| Fatal and nonfatal recurrent MI |

All patients | 6.5 | 6.1 | 0.60 | |

| PCI | 8 (6.9) | 52 (7.1) | |||

| MED | 6 (6.0) | 39 (5.1) | 0.73 | ||

| CHF class III or IV | All patients | 11.6 | 5.2 | <0.001 | |

| PCI | 9 (7.5) | 48 (5.6) | |||

| MED | 18 (16.3) | 42 (4.8) | 0.02 | ||

| Death or CHF class III or IV |

All patients | 20.5 | 14.1 | 0.005 | |

| PCI | 23 (20.8) | 108 (14.2) | |||

| MED | 22 (19.4) | 111 (14.1) | 0.60 |

CHF denotes congestive heart failure; MED, assignment to optimal medical therapy alone; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention (assignment to PCI and optimal medical therapy).

Values are reported as n (%).

Interaction between treatment and collaterals

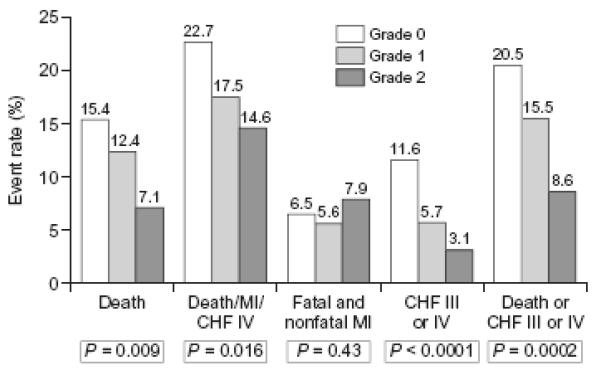

Figure 1. 60-month life table event rates as a function of baseline collateral grade irrespective of randomization group.

MI: myocardial infarction

CHF: congestive heart failure

P values from logrank tests

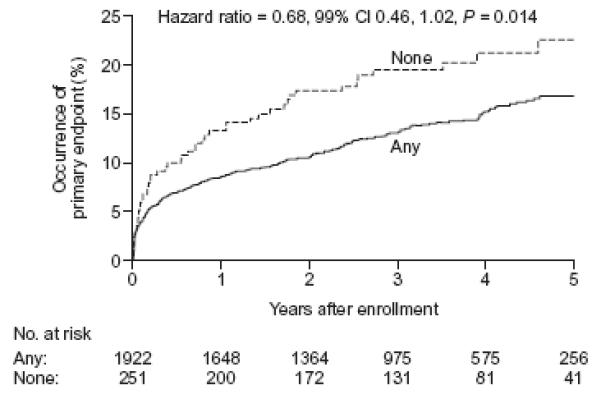

Compared to patients without visible collaterals, those with collaterals tended to reach the primary endpoint less frequently (16.9% vs 22.7 %, p=0.014). This trend which failed to reach statistical significance was observed in both treatment arms (18.0% vs 25.4% in the PCI arm; 15.9% vs 18.7% in the MED arm). Similarly, and again regardless of randomized treatment assignment, the primary endpoint tended to occur less commonly as the angiographic collateral grade increased (p for trend between 0.01 and 0.05) (Figure 1). Using the Cox proportional hazard model (Figure 2), the hazard ratio (HR) for the occurrence of primary endpoint (death, MI or CHF class IV) in patients who had any baseline collaterals was 0.68 (99% CI 0.46-1.02; P=0.014) compared with patients with no visible collaterals at baseline angiography. By multivariate analyses, however (adjusting first for variables distributed unevenly by collateral grade [history of diabetes, hypertension, Killip 2-4 class, Left anterior descending coronary as culprit artery, rales on baseline physical examination, left ventricular ejection fraction, ST segment elevation, and age] and separately by variables shown to be predictors of the OAT primary outcome [estimated glomerular filtration rate, left ventricular ejection fraction, days elapsed from qualifying myocardial infarction to randomization, history of peripheral vessel disease, history of congestive heart failure, history of diabetes, rales on baseline physical exam], or of death [estimated glomerular filtration rate, left ventricular ejection fraction, days from qualifying MI to randomization, Killip 2-4 class, history of angina, history of cerebrovascular disease, history of congestive heart failure]), the presence of collaterals was found not to be an independent predictor of the primary endpoint (p=0.67 and p= 0.85 respectively) nor of death (p= 0.79 and p=0.75 respectively).

Figure 2. Cumulative event curves for the primary composite endpoint (death, MI and CHF class-IV) by collaterals.

Solid lines: patients with grade I or II angiographic collaterals, Dotted lines : patients with grade 0 collaterals. Hazard ratio for the comparison of any vs none.

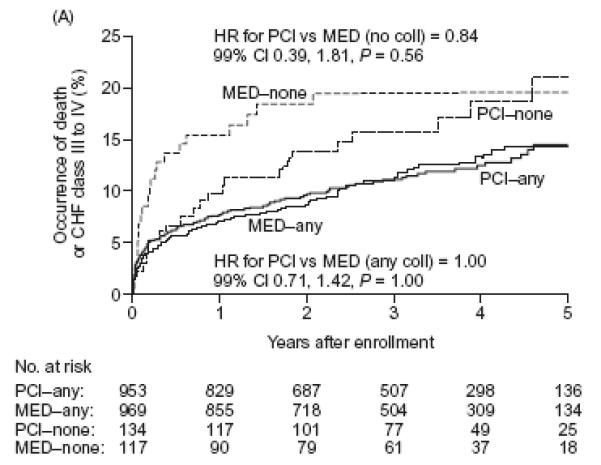

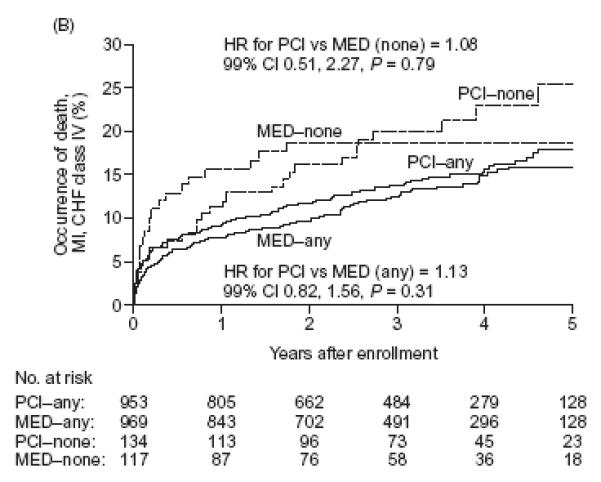

There was no interaction between the presence of collaterals and the assigned treatment (PCI vs MED) upon occurrence of the primary endpoint both when angiographic collaterals were analyzed as present or absent (Figure 3b and Table 2) or by angiographic collateral grade (Table 3). Similar observations were made when examining event rates at various time intervals during follow-up (as opposed to cumulative 60-month event rates) (data presented in supplemental electronic appendix ).

Figures 3a and 3b. Cumulative event curves for the composites of death and class III or IV CHF (Figure 3a) or death, myocardial infarction or class IV CHF (primary endpoint) (Figure 3b).

Solid lines: patients with grade I or II angiographic collaterals, Dotted lines: patients with grade 0 collaterals. thinner lines: patients randomly assigned to medical therapy only. thicker lines: patients randomly assigned to PCI on top of medical therapy

Table 3.

Cumulative 60-Month Lifetable Estimated Event Rates as a Function of Baseline Angiographic Collateral Grade

| Collateral grade | PCI event rate (n=1087) |

MED event rate (n=1086) |

P# | Hazard ratio§ |

99% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | |||||

| Grade 0 (n=251) | 16.1 | 14.8 | 0.52 | 1.29 | 0.47–3.49 |

| Grade 1 (n=1548) | 11.6 | 13.1 | 0.54 | 0.90 | 0.58–1.40 |

| Grade 2 (n=374) | 8.3 | 6.1 | 0.76 | 1.16 | 0.34–3.90 |

| P=0.81* | |||||

| Death, MI, CHF class IV | |||||

| Grade 0 (n=251) | 25.4 | 18.7 | 0.79 | 1.08 | 0.51–2.27 |

| Grade 1 (n=1548) | 17.5 | 17.4 | 0.83 | 1.03 | 0.72–1.46 |

| Grade 2 (n=374) | 19.5 | 10.5 | 0.06 | 1.80 | 0.80–4.01 |

| P=0.27* | |||||

| Fatal and nonfatal MI | |||||

| Grade 0 (n=251) | 6.9 | 6.0 | 0.81 | 1.14 | 0.28–4.58 |

| Grade 1 (n=1548) | 5.8 | 5.4 | 0.60 | 1.14 | 0.61–2.12 |

| Grade 2 (n=374) | 12.3 | 4.0 | 0.03 | 2.67 | 0.83–8.59 |

| P=0.15* | |||||

| CHF class III or IV | |||||

| Grade 0 (n=251) | 7.5 | 16.3 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.14–1.16 |

| Grade 1 (n=1548) | 6.2 | 5.2 | 0.43 | 1.20 | 0.67–2.14 |

| Grade 2 (n=374) | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.20–4.51 |

| P=0.07* | |||||

| Death or CHF III or IV | |||||

| Grade 0 (n=251) | 20.8 | 19.4 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.39–1.81 |

| Grade 1 (n=1548) | 15.4 | 15.7 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.67–1.41 |

| Grade 2 (n=374) | 9.2 | 8.1 | 0.72 | 1.15 | 0.42–3.15 |

| P=0.50* | |||||

Number of patients for PCI group: Grade 0=134, Grade 1=778, Grade 2=175.

Number of patients for MED group: Grade 0=117, Grade 1=770, Grade 2=199.

CHF denotes congestive heart failure; MED, assignment to optimal medical therapy alone; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention (assignment to PCI and optimal medical therapy).

p value for the treatment by collateral grade interaction.

p value for PCI vs MED comparison for each grade level tested by cox regression, for the entire 5 year event curves

The HR (Hazard Ratio) and 99% Confidence Intervals are for the comparisons of PCI vs MED for each Grade level.

Collaterals and secondary outcomes (Table 2)

There was no difference in the occurrence of death or reinfarction between patients with and without collaterals overall. Similarly, there was no interaction between the presence of collaterals and the assigned treatments (Tables 2 and 3). However, when collaterals were examined by grade (Figure 1), an inverse association between collateral grade and death (P for trend = 0.009) was observed. There was no such association for reinfarction.

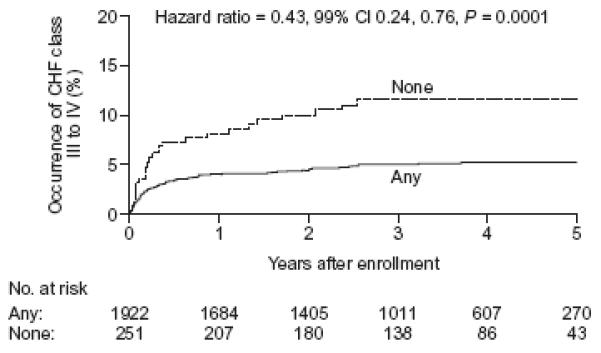

Patients with visible collaterals had a significantly lower incidence of class III or IV heart failure (5.2% vs 11.6%, p<0.001) in both treatment arms (Table 2). In a Cox proportional hazards model (Figure 4), the hazard ratio for the occurrence of CHF class III or IV in patients who had any visible collaterals was 0.43 (99% CI 0.24-0.76; P<0.001) compared with patients with no visible collaterals. When fatal events were included (the secondary composite of death or class III - IV heart failure), this relationship persisted (Tables 2 and 3). Importantly, when the presence of collaterals was examined after adjustment for variables distributed differently at baseline, or for variables predicting the primary outcome, neither the primary outcomes nor any of the secondary outcomes or their composites examined in table 2 was significantly influenced by collaterals.

Figure 4. Cumulative event curves for the occurrence of class III or IV CHF.

Solid lines: patients with grade I or II angiographic collaterals, Dotted lines: patients with grade 0 collaterals. Hazard ratio for the comparison of any vs none.

For class III-IV heart failure, we observed a trend toward interaction between the presence of collaterals and treatment effect such that patients without collaterals assigned PCI had a numerically lower incidence of heart failure when compared to similar patients assigned MED, whereas those with collaterals did not (P for interaction = 0.02). No such trend was evident when the composite of class III-IV CHF or death was analyzed. Moreover, no interaction existed between collaterals and assigned treatment for the composite of death or class III-IV heart failure (P for interaction = 0.60 when collaterals were defined in binary fashion, Table 2, or p=0.50 when collateral grade was examined, Table 3). In patients with visible collaterals, the randomized assignment to PCI or MED had no effect on the occurrence of death, or CHF class III or IV and the event curves completely overlap [HR 1.00 (99% CI 0.71-1.42; P=1.0)] (Figure 3a). In patients without collaterals, a suggestion of an early benefit of PCI was no longer evident after five years of follow-up [HR 0.84 (99% CI 0.39-1.81; P=0.56)] (Figure 3a and Table 3).

Impact of total flow to the infarct related artery

In an attempt to better characterize residual baseline (pre-PCI) flow to the infarct artery, we analyzed baseline characteristics and outcome events of patients as a function of “total flow”, i.e. the sum of collateral grades [0-2] from all non-IRA sources and the residual TIMI flow grade in IRA. Patients were grouped in 3 categories: no flow (grade 0 TT flow grade), minimal flow (grade 1) and residual flow (grades 2 to 4; there were no patients with total flow score 5). As was the case for patients with collaterals, patients with greater total flow had consistently more favorable baseline risk characteristics such as a lower age, a lower frequency of diabetes, previous myocardial infarction, anterior location, multivessel disease, Killip class 2 to 4, S3 rales, ST segment elevation (data not shown). When outcome events were analyzed as a function of total flow (Table 4), greater total flow was also consistently associated with better outcomes for all the outcome events analyzed (Death, CHF class III or IV, the primary composite endpoint, and the composite of death and CHF) except fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction, which was evenly distributed across total flow groups. There was no interaction between total flow and randomized assignment to PCI or MED, except for CHF III or IV (p=0.008), but this interaction disappeared when fatal events were included (p=0.23). By multivariate analyses, (adjusting for variables distributed differently by total flow grade and by risk factor variables for the primary outcome), the total flow grade was neither an independent predictor of the primary outcome (p=0.09 and p=0.10 respectively) nor of death (p=0.10 for both), or of CHF III or IV (p=0.10 and P=0.11 respectively).

Table 4.

Cumulative 60-Month Lifetable Estimated Event Rates According to Total Flow to the Infarct-Related Artery (in 2109 Patients with Data Available for Baseline Total Flow)

| Total flow grade | PCI event rate (n=1050) |

MED event rate (n=1059) |

P# | HR§ | 99% CI | Overall event rate (n=2109) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | ||||||

| Grade 0 (n=173) | 15.2 | 17.7 | 0.69 | 1.21 | 0.35–4.12 | 15.9 |

| Grade 1 (n=838) | 14.4 | 14.0 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.58–1.72 | 14.1 |

| Grade 2–4 (n=1098) | 8.9 | 9.2 | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.50–1.75 | 9.0 |

| P=0.74* | ||||||

| Death, MI, CHF class IV |

||||||

| Grade 0 (n=173) | 23.1 | 21.4 | 0.64 | 0.85 | 0.35–2.08 | 22.8 |

| Grade 1 (n=838) | 21.3 | 19.2 | 0.57 | 1.10 | 0.71–1.71 | 20.2 |

| Grade 2–4 (n=1098) | 16.0 | 12.5 | 0.24 | 1.24 | 0.78–1.97 | 14.2 |

| P=0.33* | ||||||

| Fatal and nonfatal MI | ||||||

| Grade 0 (n=173) | 3.6 | 9.2 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.06–2.26 | 6.0 |

| Grade 1 (n=838) | 8.2 | 6.4 | 0.22 | 1.44 | 0.67–3.09 | 7.3 |

| Grade 2–4 (n=1098) | 6.6 | 3.8 | 0.27 | 1.40 | 0.64–3.04 | 5.2 |

| P=0.21* | ||||||

| CHF III or IV | ||||||

| Grade 0 (n=173) | 6.8 | 20.0 | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.08–1.04 | 12.5 |

| Grade 1 (n=838) | 6.7 | 6.6 | 0.84 | 1.06 | 0.52–2.18 | 6.6 |

| Grade 2–4 (n=1098) | 5.5 | 3.5 | 0.22 | 1.46 | 0.66–3.21 | 4.5 |

| P=0.008* | ||||||

| Death or CHF III or IV | ||||||

| Grade 0 (n=173) | 19.6 | 21.2 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.39–1.81 | 20.6 |

| Grade 1 (n=838) | 17.8 | 17.6 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.67–1.41 | 17.6 |

| Grade 2–4 (n=1098) | 12.2 | 10.6 | 0.48 | 1.15 | 0.69–1.93 | 11.4 |

| P=0.23* | ||||||

Number of patients for PCI group: Grade 0=100, Grade 1=402, Grade 2–4=548.

Number of patients for MED group: Grade 0=73, Grade 1=436, Grade 2–4=550.

CHF denotes congestive heart failure; MED, assignment to optimal medical therapy alone; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention (assignment to PCI and optimal medical therapy).

p value for the treatment by collateral grade interaction.

p value for PCI vs MED comparison for each grade level tested by cox regression, for the entire 5 year event curves

The HR (Hazard Ratio) and 99% Confidence Intervals are for the comparisons of PCI vs MED for each Grade level.

Discussion

The open artery hypothesis suggests that late recanalization of an occluded infarct-related artery is associated with clinical benefit, independent of the myocardial salvage achieved by timely recanalization of an infarct vessel.13. This stemmed from observations that late patency of an infarct-related artery was independently associated with better LV function, electrical stability, and the potential for provision of collateral vessels to other coronary beds for during future ischemic events. However, the OAT trial demonstrated no reduction in death, recurrent MI or new class-IV heart failure attributable to routine PCI applied to persistently occluded infarct-related arteries in stable patients with persistent infarct-related artery occlusion documented 3 to 28 days after myocardial infarction8. Results from the OAT, supported by those from smaller previous trials14 have now been incorporated into both US 15 and European 16 guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction.

For the same reasons, collaterals in patients with ischemic heart disease have generally been viewed protective against the development of heart failure, reinfarction or death 17,18. Our study confirms that angiographically visible collaterals to the infarct-related artery territory at baseline angiography post MI are indeed associated with a lower risk of heart failure. Moreover, increasing collateral grade was associated with a reduction in long-term mortality, but did not affect the risk of reinfarction and had only a borderline effect on the primary composite endpoint of death, reinfarction and class IV heart failure, largely driven by its association with heart failure alone. While the presence and degree of collaterals was a correlate of improved clinical outcomes, it was not an independent predictor of clinical outcomes, indicating that the major differences in clinical characteristics at baseline associated with different angiographic collateral grades are largely responsible for the subsequent differences in outcomes. Indeed, higher collateral grades were clearly associated with lower risk characteristics at the time of randomization in the subacute phase after infarction. It is likely that higher collateral grade was responsible for some of these lower risk characteristics e.g., improved EF and less heart failure, prior to randomization (i.e. during the evolving acute myocardial infarction), by providing flow to the infarct territory despite persistent occlusion of the infarct artery. They may also be a marker of pre-infarct ischemia (stimulating their development) and ischemic preconditioning either of which could contribute to the apparent protective effect they appear to confer. by collaterals. Indeed, there are a host of data that demonstrate that the presence of collaterals during acute myocardial infarction is associated with a reduction in infarct size and improved left ventricular function1-5. However, while collaterals may protect the myocardium against ischemia during an evolving acute myocardial infarction, the presence of collaterals after the acute phase but prior to randomization was not an independent predictor of subsequent clinical outcomes, once infarction was completed. This implies that the unadjusted relationship we observed between baseline collaterals and favourable clinical outcome is largely confounded.

It is conceivable that the benefit of late recanalization of an occluded infarct artery may be greatest in patients without collateral flow to the infarct vessel territory. Therefore, it is important to examine a potential interaction between the presence of collaterals at baseline and the impact of PCI (compared to medical therapy alone) on clinical outcomes. In this analysis, the presence of collaterals at baseline angiography did not affect the outcome of the randomized comparison and there was no interaction between treatment assignment in the trial and angiographic collaterals in terms of any of the endpoints. Although there was a borderline interaction for heart failure, suggesting that PCI compared to medical therapy alone may be protective against subsequent development of non-fatal heart failure in patients without collaterals, it was no longer significant when fatal events were factored in. Thus, the potential benefit of PCI in patients without collaterals may be offset by an excess of fatal events, possibly due to the catastrophic consequences of subsequent reocclusion of the recanalized infarct artery in patients without collaterals. Angiographic data from studies such as DECOPI or TOSCA-2 have shown that reocclusion is not uncommon after late recanalization of the infarct artery19, 20.

It was intriguing to think that patients without angiographically visible collaterals to the occluded infarct-related artery may derive greater clinical benefit from recanalization of the infarct-related artery by PCI than patients who exhibit collaterals to support the infarcted area with an alternative source of blood supply to regions usually supplied by the epicardial vessels. Previous studies have shown that after recanalization of a total chronic occlusion (CTO), functional collaterals regress immediately, and are even further attenuated in long term follow up21. This may expose areas supplied by baseline collaterals to reinfarction in case of acute reocclusion of the recanalized artery, since only a minority of patients will have sufficient and immediately-recruitable collaterals in such cases 13. Therefore, our observation that the presence of angiographic collaterals at baseline angiography provided no protection against the risk of reinfarction in the present study may be partly explained by the possibility that such collaterals regress and attenuate substantially after recanalization of a total occlusion.

The present study has several strengths and limitations: it is the largest analysis addressing the association between angiographically apparent coronary collaterals and outcome, as well as their relevance for guiding revascularization in stable patients with recent myocardial infarction. Our analysis was not pre-specified. While angiographic assessment of collaterals is been employed widely, no single grading system has achieved universal acceptance. There is evidence that epicardial collaterals are an imprecise surrogate of tissue perfusion in the territory subtended by the occluded coronary and that other measures of tissue perfusion including contrast echocardiography or hemodynamic assessment of collateral circulation are better correlated to functional recovery22,23. However, these methods are impractical in the context of a large international trial or routine clinical practice. Moreover, our results were consistent regardless of whether collaterals were assessed in binary fashion, in a graded analysis or whether residual antegrade flow was taken into account in a “total flow” analysis. Finally, collaterals were assessed only at baseline prior to randomization and subsequent assessment was not available. Although this is the largest study of its type, the group with no angiographically visible collaterals was modest in size (251 patients).

Conclusion

Angiographic evidence of collaterals supplying an occluded IRA was associated with better global and segmental LV function and a lower prevalence of heart failure after myocardial infarction. However, collaterals were not an independent predictor of subsequent clinical outcomes. The presence or absence of collaterals did not influence the overall conclusion from the OAT that late recanalization of an occluded infarct artery does not reduce death, re-infarction or class-IV CHF. Decisions regarding revascularization in patients with recent myocardial infarction and occluded infarct-related arteries should not be predicated upon the presence or grade of angiographic collaterals.

Short commentary.

Collateral flow to the infarct artery territory after acute myocardial infarction may be associated with improved clinical outcomes and may also impact the benefit of subsequent recanalization of an occluded infarct-related artery. To clarify the impact of collateral flow on clinical outcomes and its interaction with the impact of PCI of an occluded infarct artery, 2173 patients with total occlusion of the infarct artery 3 to 28 days after myocardial infarction, from the OAT randomized trial were analyzed as a function of angiographic collaterals at baseline angiography. The presence and importance of angiographic collaterals at baseline were generally inversely correlated with the risk of subsequent adverse clinical outcomes and specifically associated with better left ventricular function and lower prevalence of heart failure but collateral flow was not an independent predictor of clinical outcomes, nor was there any interaction with the results of randomized treatment assignment on clinical outcomes: late recanalization of the infarct artery in addition to medical therapy showed no benefit compared to medical therapy alone, regardless of the presence or absence of collaterals. Therefore, while collaterals may protect the myocardium against ischemia during an evolving acute myocardial infarction, the presence of collaterals after the acute phase was not an independent predictor of subsequent clinical outcomes, once infarction was completed. In addition, clinical decisions in patients with recent myocardial infarction should not be based on the presence or grade of angiographic collaterals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who enrolled in the study, their physicians, and the staff at the study sites for their important contributions; and Zubin Dastur and Emily Levy for their assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding Sources: The project described was supported by Award Numbers U01 HL062509 and U01 HL062511 from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute.The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Supplemental grant funds and product donations equivalent to 6% of total study cost from: Eli Lilly, Millennium Pharmaceuticals and Schering Plough, Guidant, Cordis/Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic, Merck and Bristol Myers Squibb Medical Imaging.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr Steg reports receiving research support from Sanofi-Aventis, and honoraria as consultant or speaker from AstraZeneca, Astellas, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, BMS, Endotis, GSK, MSD, Medtronic, Nycomed, sanofi-aventis, Servier, Takeda, The Medicines Company. Dr Hochman received grant support to her institution from Eli Lilly and Bristol Myers Squibb Medical Imaging and product donation from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Schering-Plough, Guidant, and Merck for OAT and received honoraria for Steering Committee service from Eli Lilly and Glaxo Smith Kline and honoraria for serving on the Data Safety Monitoring Board of a trial supported by Schering-Plough. Dr Mancini received a research grant from Cordis and honoraria of <$10,000/yr from Pfizer, Merck Frosst Canada, AstraZeneca, GSK, and Sanofi Aventis. Dr. White received research grants from Sanofi Aventis, Eli Lilly, The Medicines Company, Pfizer, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Schering Plough, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Astra Zeneca, GSK, and Daiichi Sankyo Pharma Development and received consultant fees of <$10,000 from GSK and Sanofi Aventis.

NIH PubMed Central Policy: We request the journal to acknowledge that the Author retains the right to provide a copy of the final manuscript to the NIH upon acceptance for Journal publication, for public archiving in PubMed Central as soon as possible but no later than 12 months after publication by Journal.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Elsman P, van ‘t Hof AW, de Boer MJ, Hoorntje JC, Suryapranata H, Dambrink JH, Zijlstra F, Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group Role of collateral circulation in the acute phase of ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:854–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirai T, Fujita M, Nakajima H, Asanoi H, Yamanishi K, Ohno A, Sasayama S. Importance of collateral circulation for prevention of left ventricular aneurysm formation in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1989;79:791–796. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.4.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodama K, Kusuoka H, Sakai A, Adachi T, Hasegawa S, Ueda Y, Mishima M, Hori M, Kamada T, Inoue M, Hirayama A. Collateral channels that develop after an acute myocardial infarction prevent subsequent left ventricular dilation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1133–1139. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00596-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habib GB, Heibig J, Forman SA, Brown BG, Roberts R, Terrin ML, Bolli R. Influence of coronary collateral vessels on myocardial infarct size in humans. Results of phase I thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) trial. The TIMI Investigators. Circulation. 1991;83:739–746. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishihara M, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, Shimatani Y, Kurisu S, Hata T, Mitsuba N, Kisaka T, Nakama H, Kijima Y. Comparison of the cardioprotective effect of prodromal angina pectoris and collateral circulation in patients with a first anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:622–625. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Castellano N, Garcia EJ, Abeytua M, Soriano J, Serrano JA, Elizaga J, Botas J, Lopez-Sendon JL, Delcan JL. Influence of collateral circulation on in-hospital death from anterior acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:512–518. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00521-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antoniucci D, Valenti R, Moschi G, Migliorini A, Trapani M, Santoro GM, Bolognese L, Cerisano G, Buonamici P, Dovellini EV. Relation between preintervention angiographic evidence of coronary collateral circulation and clinical and angiographic outcomes after primary angioplasty or stenting for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Reynolds HR, Abramsky SJ, Forman S, Ruzyllo W, Maggioni AP, White H, Sadowski Z, Carvalho AC, Rankin JM, Renkin JP, Steg PG, Mascette AM, Sopko G, Pfisterer ME, Leor J, Fridrich V, Mark DB, Knatterud GL, Occluded Artery Trial Investigators Coronary intervention for persistent occlusion after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2395–2407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Knatterud GL, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Mark DB, Reynolds HR, White HD, Occluded Artery Trial Research Group Design and methodology of the Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) Am Heart J. 2005;150:627–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagajothi N, Velazquez-Cecena JL, Khosla S. Persistent coronary occlusion after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1681. author reply 1683-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong B. Persistent coronary occlusion after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1681–2. author reply 1683-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruk M, Kadziela J, Reynolds HR, Forman SA, Sadowski Z, Barton BA, Mark DB, Maggioni AP, Leor J, Webb JG, Kapeliovich M, Marin-Neto JA, White HD, Lamas GA, Hochman JS. Predictors of Outcome and the Lack of Effect of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Across the Risk Strata in Patients With Persistent Total Occlusion After Myocardial Infarction: Results From the OAT (Occluded Artery Trial) Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Intv. 2008;1:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braunwald E. Myocardial reperfusion, limitation of infarct size, reduction of left ventricular dysfunction, and improved survival. Should the paradigm be expanded? Circulation. 1989;79:441–444. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ioannidis JP, Katritsis DG. Percutaneous coronary intervention for late reperfusion after myocardial infarction in stable patients. Am Heart J. 2007;154:1065–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Halasyamani LK, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC, Jr, 2004 Writing Committee Members. Anbe DT, Kushner FG, Ornato JP, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW. 2007 Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration With the Canadian Cardiovascular Society endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians: 2007 Writing Group to Review New Evidence and Update the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, Writing on Behalf of the 2004 Writing Committee. Circulation. 2008;117:296–329. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fox K, Huber K, Kastrati A, Rosengren A, Steg PG, Tubaro M, Verheugt F, Weidinger F, Weis M. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry C, Balachandran KP, L‘Allier PL, Lespérance J, Bonan R, Oldroyd KG. Importance of collateral circulation in coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:278–291. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regieli JJ, Jukema JW, Nathoe HM, Zwinderman AH, Ng S, Grobbee DE, van der Graaf Y, Doevendans PA. Coronary collaterals improve prognosis in patients with ischemic heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.11.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dzavik V, Buller CE, Lamas GA, Rankin JM, Mancini GB, Cantor WJ, Carere RJ, Ross JR, Atchison D, Forman S, Thomas B, Buszman P, Vozzi C, Glanz A, Cohen EA, Meciar P, Devlin G, Mascette A, Sopko G, Knatterud GL, Hochman JS, TOSCA-2 Investigators Randomized trial of percutaneous coronary intervention for subacute infarct-related coronary artery occlusion to achieve long-term patency and improve ventricular function: the Total Occlusion Study of Canada (TOSCA)-2 trial. Circulation. 2006;114:2449–2457. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steg PG, Thuaire C, Himbert D, Carrié D, Champagne S, Coisne D, Khalifé K, Cazaux P, Logeart D, Slama M, Spaulding C, Cohen A, Tirouvanziam A, Montély JM, Rodriguez RM, Garbarz E, Wijns W, Durand-Zaleski I, Porcher R, Brucker L, Chevret S, Chastang C, DECOPI Investigators DECOPI (DEsobstruction COronaire en Post-Infarctus): a randomized multi-centre trial of occluded artery angioplasty after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:2187–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner GS, Emig U, Mutschke O, Schwarz G, Bahrmann P, Figulla HR. Regression of collateral function after recanalization of chronic total coronary occlusions: a serial assessment by intracoronary pressure and Doppler recordings. Circulation. 2003;108:2877–2882. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000100724.44398.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Liebergen RA, Piek JJ, Koch KT, de Winter RJ, Schotborgh CE, Lie KI. Quantification of collateral flow in humans: a comparison of angiographic, electrocardiographic and hemodynamic variables. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:670–677. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karila-Cohen D, Czitrom D, Brochet E, Steg PG. Lessons from myocardial contrast echocardiography studies during primary angioplasty. Heart. 1997;78:331–2. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.4.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.