Abstract

A variety of stress stimuli, including ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, induce the transcriptional repressor ATF3 in the kidney. The functional consequences of this upregulation in ATF3 after renal I/R injury are not well understood. Here, we found that ATF3-deficient mice had higher renal I/R-induced mortality, kidney dysfunction, inflammation (number of infiltrating neutrophils, myeloperoxidase activity, and induction of IL-6 and P-selectin), and apoptosis compared with wild-type mice. Furthermore, gene transfer of ATF3 to the kidney rescued the renal I/R-induced injuries in the ATF3-deficient mice. Molecular and biochemical analysis revealed that ATF3 interacted directly with histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and recruited HDAC1 into the ATF/NF-κB sites in the IL-6 and IL-12b gene promoters. The ATF3-associated HDAC1 deacetylated histones, which resulted in the condensation of chromatin structure, interference of NF-κB binding, and inhibition of inflammatory gene transcription after I/R injury. Taken together, these data demonstrate epigenetic regulation mediated by the stress-inducible gene ATF3 after renal I/R injury and suggest potential targeted approaches for acute kidney injury.

Acute renal failure represents a common clinical problem associated with high morbidity and mortality.1 Renal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury is the major cause of acute renal failure after major surgery or renal transplantation.2 Inflammation is a key mechanism leading to organ damage after renal I/R injury3; however, the endogenous anti-inflammatory pathway protecting against renal I/R-induced injury has not been extensively explored.

Chromosomal remodeling by histone acetylation or deacetylation plays an important role in the regulation of transcriptional activity.4,5 Histone acetylation mediated by histone acetyltransferases relaxes chromatin structure and allows for access by positive transcriptional regulators, thereby promoting transcriptional activation. In contrast, the reverse reaction is catalyzed by histone deacetylases (HDACs), which leads to histone deacetylation, chromatin condensation, and prevention of transcription factor access, and thus transcriptional repression. HDACs have recently been shown to be involved in ischemic injury in the brain6,7 and heart.8,9 However, whether HDAC plays an important role in the regulation of renal I/R injury is unknown.

ATF3 belongs to the activating transcription factor/cAMP responsive element-binding protein (ATF/CREB) family of transcription factors. Unlike its name, the homodimer of ATF3 represses rather than activates transcription from various promoters with ATF/CREB sites.10 ATF3 is induced by various physiologic and pathologic stimuli.11 In cultured cells, ATF3 is up-regulated by various stress signals, including elevated temperature, cytokine, genotoxic agents, and cytotoxic agents. In animal study, ATF3 is induced in the heart, liver, and kidney with I/R injury.12–14 Recent reports demonstrated that ATF3 attenuates the inflammatory responses associated with Toll-like receptor activation15 and allergic airway disease.16 In addition, adenovirus-mediated overexpression of ATF3 protected human proximal tubular cells or mice against H2O2-induced cell death or renal I/R injury.17 However, the specific role of ATF3 in inflammatory responses triggered by renal I/R injury remains elusive.

In the present study, we used in vivo loss-of-function and gain-of-function approaches, together with molecular and biochemical analyses, to unravel the role of ATF3 as an endogenous anti-inflammatory factor and its protective role after renal I/R injury. Our data suggest that ATF3 contributes to the negative regulation of inflammatory cytokine gene expression by recruiting HDAC1 to ATF/NF-κB-binding sites and curtails the production of inflammatory cytokine genes, thereby preventing damaging inflammatory responses after ischemic renal I/R injury.

Results

ATF3 Is Induced in a Mouse Ischemic Renal Failure Model.

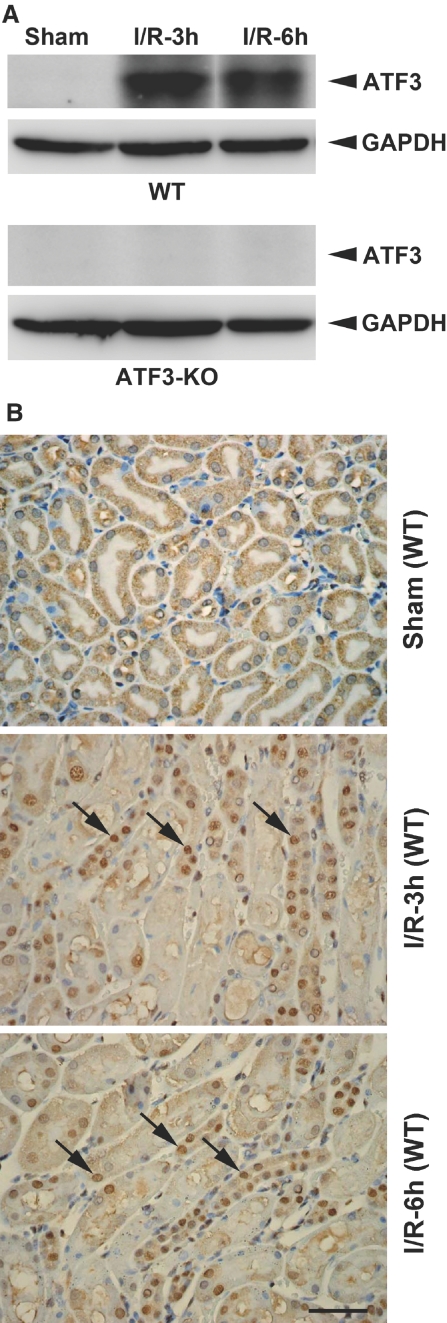

To investigate the role of ATF3 in I/R injury, we first characterized the induction of ATF3 in the kidney of a mouse model of I/R injury. Western blot analysis revealed ATF3 protein level significantly increased in the wild-type (WT) kidney as early as 3 hours after I/R injury (Figure 1A, top). However, no ATF3 protein was detected in renal tissue from ATF3-knockout (KO) animals, which confirms the complete gene inactivation in KO animals (Figure 1A, bottom). Interestingly, immunohistochemical analysis revealed ATF3 staining of tubular epithelial cells predominantly within the nucleus after I/R injury (Figure 1B). Together, these observations suggest that the ischemic-responsive gene ATF3 may function as a transcriptional regulator under the renal I/R injury condition.

Figure 1.

Renal ATF3 is induced upon I/R injury in WT or ATF3-KO mice. (A) Western blot analysis of ATF3 protein in kidney homogenates from I/R-treated WT and ATF3-KO mice. (B) Localization of ATF3 in the kidney tissue of sham-operated or I/R-treated WT mice by immunohistochemical staining. Arrows indicate ATF3 nuclear staining of tubular epithelial cells. h, hours. Bar = 50 μm.

Role of ATF3 in I/R-Induced Renal Function, Apoptotic, and Inflammatory Responses.

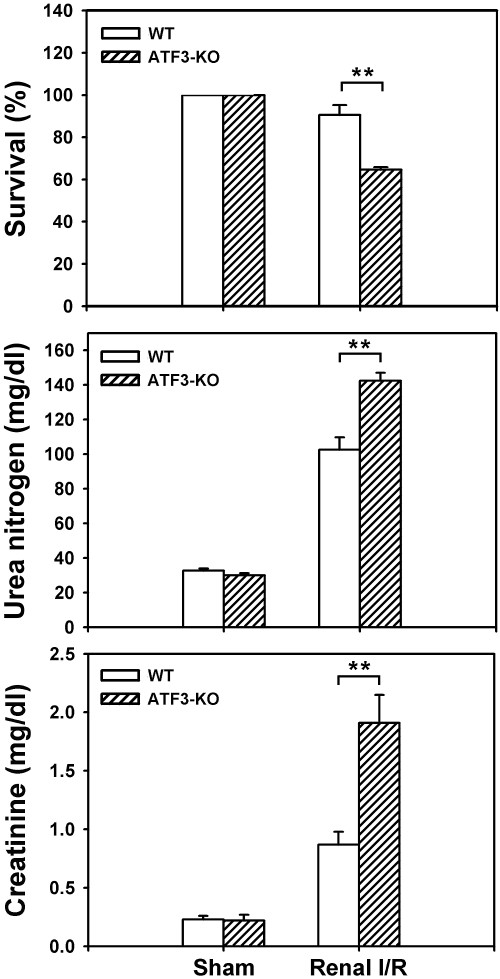

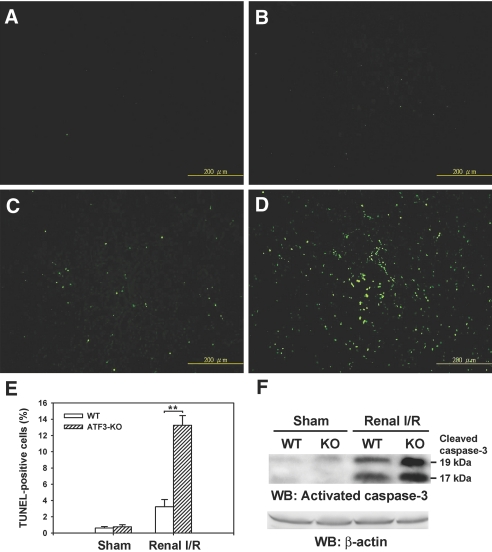

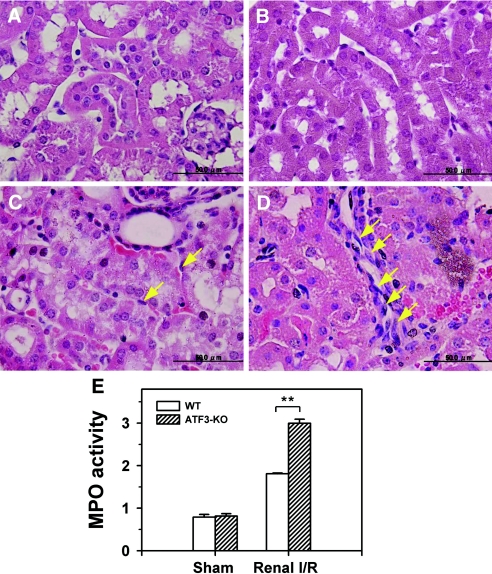

To further address the pathologic involvement of ATF3 in I/R injury, we directly compared the survival and renal function (as measured by levels of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine) of WT and ATF3-KO mice under sham operation or renal I/R surgery. As shown in Figure 2, I/R-induced mortality and renal dysfunction were significantly increased in ATF3-KO mice compared with their WT counterparts. The increased death and enhanced renal dysfunction in ATF3-KO mice were accompanied by elevated activity of the cleaved, active form of caspase-3 and increased number of apoptotic [terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL)]-positive tubular epithelial cells (Figure 3). Furthermore, histologic analysis of kidney tissue from I/R-treated ATF3-KO mice showed an accumulation of neutrophils in the peritubular region and elevation of myeloperoxidase activity, a major constituent of neutrophils, compared with WT mice under I/R injury (Figure 4, C–E).

Figure 2.

I/R decreases overall survival and kidney function in WT and ATF3-KO mice. Age-matched WT and ATF3-KO mice underwent sham operation or I/R and then were monitored for survival 2 days later (top). Survival rates are means ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 8 animals in each group). Serum levels of urea nitrogen (middle) and creatinine (bottom) were measured 24 hours after reperfusion or sham surgery. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6 mice in each group). **P < 0.01, WT versus ATF3-KO.

Figure 3.

I/R increases renal tubular epithelial cell apoptosis in WT and ATF3-KO mice. WT (A and C) and ATF3-KO (B and D) mice underwent sham operation (A and B) or I/R injury (renal ischemia for 45 minutes, then 18 hours of reperfusion; C and D). TUNEL staining of representative kidney sections from each experimental group is shown. Bar = 200 μm. (E) Quantitative analysis of TUNEL-positive renal epithelial nuclei per total nuclei in WT and ATF3-KO mice after sham operation or I/R injury (n = 5 mice per group). (F) Active caspase-3 protein expression. Kidney lysates from WT and ATF3-KO mice subjected to sham operation and renal I/R were probed with specific antibody against the cleaved, active form of caspase-3. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. WB, Western blot. **P < 0.01, WT versus ATF3-KO.

Figure 4.

I/R increases polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in WT and ATF3-KO mice. Sham-operated (A and B) and I/R-injured (C and D) WT (A and C) and ATF3-KO (B and D) mice. A significant number of infiltrating polymorphonuclear leukocytes (yellow arrows) accumulated in the ATF3-KO kidney (D), with fewer in the WT (C) kidney. (E) MPO activity in renal tissue samples obtained from WT and ATF3-KO mice after sham operation or I/R injury. MPO activity is expressed as ΔOD460/min per milligram of protein. **P < 0.01, WT versus ATF3-KO. Figures are representative of three experiments performed on different days (n = 5 mice in each group). Bar = 50 μm.

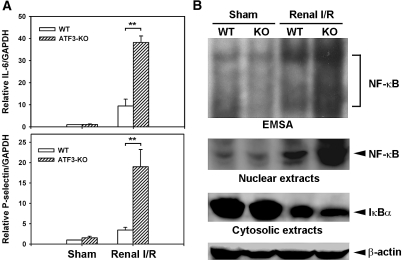

I/R-induced local expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules plays a critical role in amplifying ischemic tissue injury.18–21 For example, expression of inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and adhesion molecule P-selectin is induced in ischemic renal tissues, and its inhibition protects against I/R-induced renal failure in mice.20,21 We thus compared the expression of IL-6 and P-selectin in kidneys of WT and ATF3-KO mice under renal I/R injury. As shown in Figure 5, compared with WT controls, ATF3-KO mice showed marked elevation in the mRNA level of IL-6 and P-selectin.

Figure 5.

I/R injury increases the expression of IL-6 and P-selectin or NF-κB DNA-binding activity in WT and ATF3-KO renal tissues. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of IL-6 and P-selectin from renal cDNA derived from mice subjected to sham surgery or renal I/R injury (3 hours after ischemia). Expression was normalized to that of GAPDH. Experiments were performed twice with similar results (n = 5 mice in each group). **P < 0.01, WT versus ATF3-KO. (B) NF-κB nuclear translocation, activation, and IκB degradation. (Top) EMSA results of NF-κB expression in renal nuclear extracts of WT and ATF3-KO mice subjected to sham operation or I/R injury. (Bottom) Nuclear or cytosolic extracts were probed with anti-NF-κB or anti-IκB antibody, respectively, to quantify protein levels in these subcellular compartments. Anti-β-actin served as a loading control.

NF-κB is a transcription factor with a heterodimer of p50 and p65 subunits that plays an important role in inflammatory responses by regulating the expression of cytokines, adhesion molecules, chemokines, and growth factors.22 Because the IL-6 and P-selectin gene promoters contain functional NF-κB-binding sites essential for their induction in response to inflammatory stimuli,23,24 we further assessed NF-κB activation by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Renal I/R injury caused increased NF-κB DNA-binding activity in nuclear extracts from WT kidneys, which was further markedly increased in ATF3-KO kidneys (Figure 5B, top). The identity of the gel shift bands was verified by competition and supershift analysis with a specific antibody against the NF-κB p65 subunit (data not shown). Furthermore, the increased NF-κB activation was accompanied by a concomitant elevation in the total amount of NF-κB protein present in the nuclei and a simultaneous decrease in cytosolic IκBα, an inhibitory protein that prevents translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus (Figure 5B, middle and bottom). Consistent with this observation, the expression of several other NF-κB-dependent inflammatory cytokines/chemokines (IL-12b and MCP-1) and adhesion molecules (E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1) was higher in the kidneys of I/R-treated ATF3-KO mice than in WT controls (data not shown).

Validation or Rescue of the Protective Role of ATF3 by Gain-of-Function Adenovirus or Adeno-Associated Virus-Mediated Gene Transfer.

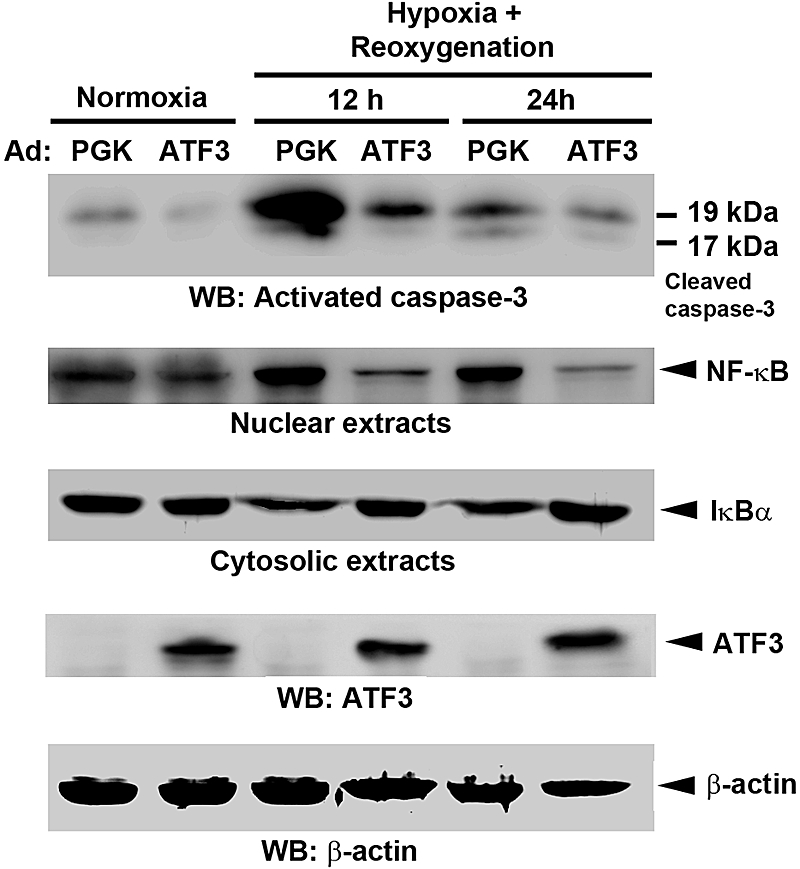

As a complementary approach to the knockout mouse studies, we further used the gain-of-function method of adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of ATF3. Cultured proximal tubular cells (NRK-52E) were transduced with recombinant adenovirus carrying ATF3 or phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) as a control followed by normoxia or hypoxia-reoxygenation (H/R) treatment. As shown in Figure 6 and Supplemental Figure 1, the apoptotic (caspase-3 activation) and inflammatory responses (NF-κB nuclear translocation, cytosolic IκBα degradation, or expression of IL-6 and IL-12b mRNA) induced by H/R were markedly suppressed in cells overexpressing ATF3 compared with control PGK cells.

Figure 6.

Adenovirus-mediated expression of ATF3 decreases apoptotic and inflammatory signaling. Renal proximal tubule epithelial (NRK-52E) cells were transduced with the control adenovirus (Ad:PGK) or Ad:ATF3 (multiplicity of infection = 30) for 24 hours before being subjected to normoxia or hypoxia (24 hours), and then reoxygenation for 12 or 24 hours. Cell lysates were probed with specific antibody against the cleaved, active form of caspase-3, NF-κB (nuclear extracts), and IκBα (cytosolic extracts). The protein expression of ATF3 was confirmed by Western blot (WB) analysis. Note that induction of endogenous ATF3 protein under hypoxia/reoxygenation can be detected after a longer exposure (Supplemental Figure 9). Anti-β-actin served as a loading control. Experiments were performed twice with similar results.

Likewise, we were able to rescue the renal I/R-induced animal death (increased survival rate), renal dysfunction (decreased blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels), and apoptotic responses (suppressed caspase-3 activation and reduced TUNEL-positive cell number) by in vivo adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated gene transfer of ATF3 into ATF3-KO kidneys (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3). Together, our data suggest that ATF3 plays a protective role after renal I/R injury, at least through its antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory action.

ATF3 Binds and Suppresses NF-κB-Dependent IL-6 and IL-12b Gene Transactivation.

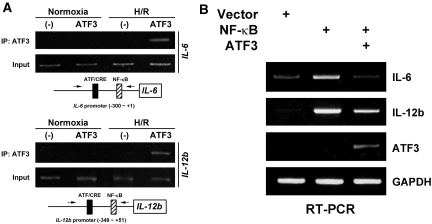

To further explore the molecular mechanism by which ATF3 inhibits the I/R-induced inflammation, we first examined the ATF3-binding sites in the IL-6 and IL-12b gene promoters and identified a single site closely apposed to the NF-κB binding site within the proximal region of each promoter.15 Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay, we then determined whether ATF3 could be recruited to the IL-6 or IL-12b gene promoter site in renal tubular epithelial cells. When anti-FLAG antibody was used to immunoprecipitate the overexpressed ATF3 (FLAG-tagged), the proximal promoter region of the IL-6 or IL-12b gene was efficiently immunoprecipitated after H/R treatment compared with the normoxia condition (Figure 7A). In agreement with our in vivo studies, recruitment of ATF3 antagonized the NF-κB-dependent induction of IL-6 or IL-12b in renal tubular epithelial cells (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Recruitment of ATF3 to the proximal promoter region of IL-6 and IL-12b suppresses the expression of these inflammatory genes. (A) ChIP assay. NRK-52E cells were transfected with an empty vector as a negative control (−) or the expression plasmid encoding ATF3 (FLAG-tagged) for 24 hours before being subjected to normoxia or hypoxia (24 hours), and then reoxygenation for 6 hours (H/R). Cell lysates were cross-linked with formaldehyde, and ChIP assay involved use of anti-FLAG antibody (for ATF3). Immunoprecipitated (IP) DNA was amplified by PCR for the proximal promoter region of IL-6 (top) or IL-12b (bottom). Arrows indicate the PCR primers used for ChIP assays. (B) ATF3 inhibits NF-κB-induced IL-6 or IL-12b expression. NRK-52E cells were transfected with the empty expression plasmid (Vector), NF-κB (two plasmids encoding for the p50 or p65 subunit), or NF-κB together with the ATF3 (FLAG epitope-tagged) expression plasmid. Results are from RT-PCR analysis of the expression of NF-κB-induced IL-6 or IL-12b relative to that of GAPDH 2 days after transfection. Note that the endogenous ATF3 expression is not visible because the primers used for RT-PCR analysis are specific for only FLAG-tagged ATF3, not endogenous ATF3. Experiments were performed twice with similar results.

ATF3 Regulates Histone Acetylation by Recruiting HDAC1 at the IL-6 and IL-12b Gene Promoter.

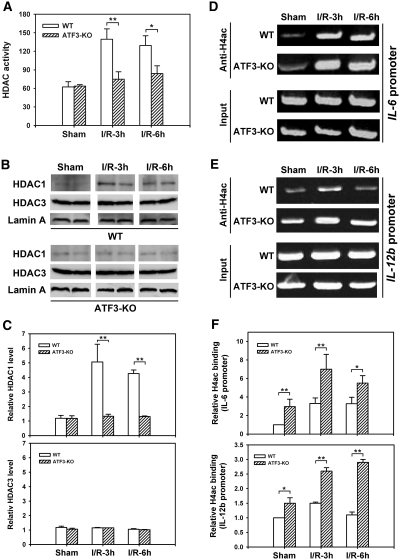

Chromatin remodeling is well known to modulate transcription by promoting or preventing the access of transcription factors to their promoter-binding sites.4,5 Histone acetyltransferases and HDACs play critical roles in chromatin remodeling by catalyzing the acetylation and deacetylation of histones. As such, acetylation relaxes the chromatin structure, thus allowing access of transcription factors to gene promoters, whereas deacetylation changes the chromatin structure to limit transcription factor access.4,5 Because the p65/RelA subunit of NF-κB interacts with the corepressor HDAC1 to suppress NF-κB-dependent gene expression,25 and ATF3-mediated HDAC1 recruitment and associated histone deacetylation inhibit NF-κB activation in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages,15 we determined the total HDAC activity and the presence of HDAC1 protein in kidney nuclear extracts from WT and ATF3-KO mice in response to I/R insult. A significant increase in HDAC activity and the specific presence of nuclear HDAC1 but not HDAC3 occurred as early as 3 hours after I/R from kidney nuclear extracts derived from WT mice but not from ATF3-KO mice (Figure 8, A–C). Intriguingly, this I/R-induced nuclear HDAC1 protein expression but not mRNA expression (see Supplemental Figure 4) parallels the induction of nuclear ATF3 protein (Figure 1), which implies a potential functional association of ATF3 with HDAC1 under I/R stress. Indeed, further anti-HDAC1 ChIP experiments demonstrated that HDAC1 is recruited to the promoters of IL-6 and IL-12b genes under I/R in an ATF3-dependent manner (Supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 8.

I/R injury increases nuclear histone deacetylase activity, HDAC1 or HDAC3 nuclear localization, and H4 acetylation on the IL-6 or IL-12b gene promoter in WT and ATF3-KO kidneys. Kidney nuclear extracts derived from sham-operated or I/R-treated WT or ATF3-KO mice were used to determine total HDAC activity (A), HDAC1 or HDAC3 protein levels by Western blot analysis (B), or dynamics of H4 acetylation (H4ac) on the IL-6 or IL-12b promoter by ChIP assay (D and E), as described in Concise Methods. (C) Histographic quantification of nuclear HDAC1 or HDAC3 protein levels in respective groups shown in B (quantified by densitometric scanning and normalized to nuclear lamin A protein level). (F) Quantification of anti-H4ac ChIP analysis in D or E. For semiquantitative analysis, PCR reactions involved genomic DNA obtained from each sample before immunoprecipitation, noted as “Input.” The relative values for anti-H4ac ChIP assays were quantified by densitometric scanning and normalized to the values of “input.” The value from the WT sham animal group was set to 1. Data are means ± SEM (n = 3 in each group) in A or F. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. h, hours. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, WT versus ATF3-KO.

We then assessed whether the ATF3-mediated, HDAC1-dependent chromatin remodeling takes place on the IL-6 and IL-12b gene promoter by determining histone acetylation status by ChIP assay after renal I/R insult. In WT animals, acetylated histone H4 (H4ac), an indicator of open chromatin structure, bound to the IL-6 or IL-12b gene promoter within 3 hours, then the level was maintained at the IL-6 promoter or was decreased at the IL-12b promoter 6 hours after I/R (Figure 8, D–F). However, in the ATF3-KO kidney, deacetylation of histone H4 did not occur, and the level of H4ac remained at a higher level than that for the WT kidney (Figure 8, D–F). As a negative control, similar experiments were performed with primers specific for the mouse GAPDH proximal promoter, showing that other chromatin marks are not targets of HDAC1-mediated epigenetic modification (Supplemental Figure 6). Together, these results indicate that ATF3 may functionally interact with HDAC1 and that the ATF3-associated HDAC1 recruitment is important for dynamic histone deacetylation after I/R injury.

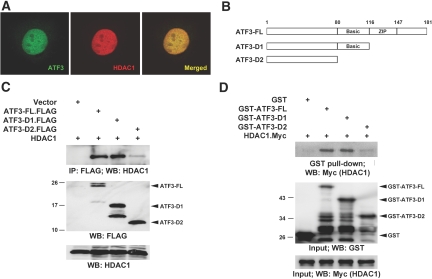

In support of this notion, we found that ATF3 colocalizes with HDAC1 in the nuclei when coexpressed in the same cells (Figure 9A). Consistently, coimmunoprecipitation assay demonstrated that ATF3 (FLAG-tagged) was immunoprecipitated specifically with HDAC1 protein (Figure 9C). Furthermore, an in vitro binding assay study was performed using recombinant ATF3 and HDAC1 proteins. As shown in Figure 9D, glutathione S transferase (GST)-ATF3-FL and Myc-tagged HDAC1 physically interact with each other, as detected by GST pull-down assay. We also performed a deletion analysis of ATF3 to define the region responsible for HDAC1 binding. As illustrated in Figure 9, C and D, HDAC1 was coprecipitated efficiently with the ATF3-FL or ATF3-D1 mutant, whereas the ATF3-D2 mutant lacking the basic region (residues 80 to 116) weakly bound HDAC1. Most importantly, we also demonstrated that endogenous ATF3 indeed interacts with HDAC1 after I/R injury in the kidney (Supplemental Figure 7). Together, these data indicate that ATF3 directly binds HDAC1 under the renal I/R condition, and the basic region plays a critical role in this interaction.

Figure 9.

Nuclear colocalization and complex formation of ATF3 with HDAC1. (A) Colocalization of ATF3 with HDAC1 in the cell nuclei. HEK-293T cells cotransfected with the expression plasmids for ATF3 (FLAG-tagged) and HDAC1 (Myc-tagged) were stained with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (for ATF3; green), and anti-Myc polyclonal antibody (HDAC1; red), then were examined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Overlay of the two images is shown (merged), with colocalization appearing as yellow. (B) Diagram of ATF3 full-length (FL) and two C-terminal deletion mutants used for binding assay. (C and D) Biochemical interaction between ATF3 and HDAC1 in vivo and in vitro. The HDAC1 expression plasmid was transfected alone or in combination with the expression plasmids encoding FLAG-tagged ATF3-FL or two deletion D1 and D2 proteins in HEK-293T cells. Two days later, cell lysates underwent immunoprecipitation (intraperitoneally) and Western blot (WB) analysis with antibodies as indicated to determine the protein-protein interactions (C). ATF3 (FL, D1, and D2) or HDAC1 was expressed as GST fusion proteins or C-terminally tagged with Myc (HDAC1.Myc) by in vitro translation, respectively. Binding of these proteins in vitro was assayed by GST pull-down assay (D). Input was 10% of total.

HDAC1 Is Required for Limiting the Renal I/R-Induced Injury.

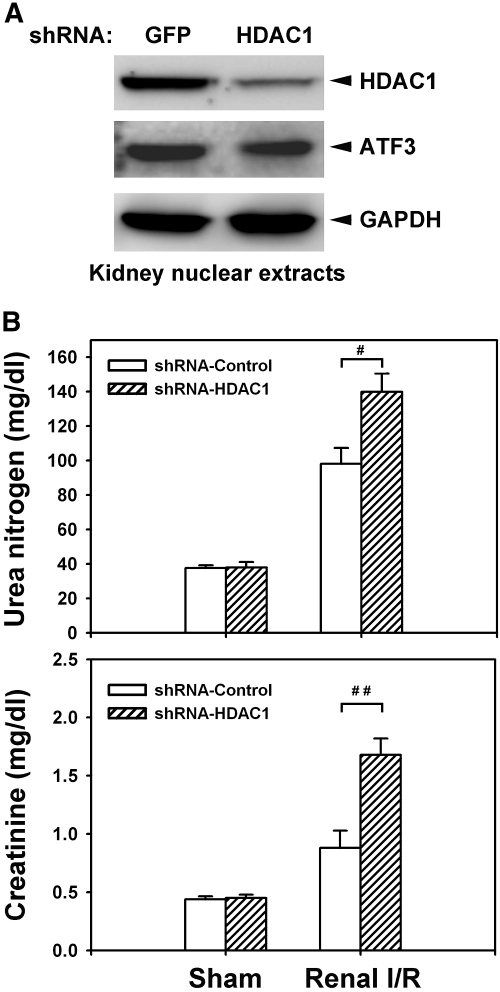

To further validate the significance of ATF3-mediated HDAC1 recruitment after I/R, we then asked whether in vivo silencing of HDAC1 has an effect on renal I/R-induced injury to recapitulate the enhanced inflammatory responses and renal dysfunction seen in the ATF3-KO mice. As shown in Figure 10A, local perfusion of the recombinant lentivirus encoding short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) for HDAC1 knockdown could effectively and specifically silence the expression of HDAC1 (more than 80% less protein compared with the control) in the tubular epithelial cells of kidney (Supplemental Figure 8). We then evaluated the effect of in vivo HDAC1 knockdown on I/R-induced renal dysfunction and the inflammatory response. As shown in Figure 10B, silencing of HDAC1 further enhanced renal dysfunction (increased blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels) and increased the expression of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-12b (data not shown) induced by I/R injury, which confirms the critical involvement and functional importance of HDAC1 in ATF3-mediated epigenetic change and protection after renal I/R.

Figure 10.

HDAC1 knockdown increases I/R-induced renal dysfunction. (A) Lentivirus-mediated short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown of HDAC1 in the kidney. The recombinant lentivirus carrying shRNA for HDAC1 or green fluorescent protein (GFP) as controls (1 × 109 viral particles per animal) was perfused into the WT kidney through renal artery. Two weeks after transduction, the nuclear extracts derived from the kidney transduced with lentivirus for GFP or HDAC1 were probed with anti-HDAC1, anti-ATF3, or anti-GAPDH antibody to validate the efficiency and specificity of the knockdown. (B) HDAC1 is required for limiting the I/R-induced renal dysfunction. Control (GFP or empty virus) or HDAC1-KO mice underwent sham operation or I/R injury for 8 hours. Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels, indicators for renal function, were measured. Data are means ± SEM (n = 5 in each group). #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01, shRNA-GFP versus shRNA-HDAC1 knockdown.

Discussion

Although ATF3 was recognized more than a decade ago as an immediate early response gene induced by various stress signals,10,11 including I/R injury in the kidney, the precise function of I/R-induced ATF3 expression in the kidney remains largely unknown. Our results suggest that stress-induced ATF3 plays a protective role after renal I/R injury, at least through anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic effects in renal tubular epithelial cells. Further molecular and biochemical analyses demonstrated that ATF3 can physically interact with and recruit corepressor HDAC1 to the promoters of inflammatory genes (e.g., IL-6 or IL-12b) that contain the ATF/NF-κB-binding sites to inhibit transcription via chromatin structural remodeling, which attenuates inflammatory responses and restricts tissue damage associated with renal I/R.

Although this study revealed the cellular protective role of ATF3 during renal I/R injury, of note, ATF3 was also shown to execute its proapoptotic function in the context of other stress conditions.26–30 For example, ATF3 has been implicated in cytokine-induced or nitric oxide-induced β-cell apoptosis in the pancreas,27 plays a role in homocysteine-induced endothelial cell death,28 and promotes cancer cell death.29,30 Regardless, because ATF3 is rapidly induced on I/R injury in the brain,31 heart,13 or liver,14 in addition to the kidney, ATF3 may protect these organs against I/R-induced damage, such as ischemic stroke in the brain or acute myocardial infarction in the heart, which will be examined in future studies.

The mechanism underlying the ATF3-mediated antiapoptotic effect under renal I/R injury is unclear. However, ATF3 may exert its apoptotic effect by transcriptional control of apoptosis-related genes. In support of this notion, a recent in vitro study showed that oxidative stress-induced ATF3 expression is associated with the down-regulation of p53 (which can cause apoptosis) and induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (which plays a critical role in apoptosis through regulation of the cell cycle) in cultured renal proximal-tubular HK2 cells.17 Therefore, the oxidative stress-mediated suppression of p53 or up-regulation of p21 associated with ATF3 overexpression may contribute to the protection against renal I/R injury directly by inhibiting apoptosis or indirectly through cell cycle G1 arrest. Thus, additional studies are needed to further explore whether these mechanisms are important for the antiapoptotic effect mediated by ATF3 in vivo.

ATF3 as a homodimer has been shown to act as a transcriptional repressor32,33; however, ATF3 can also function as a transactivator when it is heterodimerized with other basic leucine zipper proteins, such as c-Jun or JunB protein.34 In line with this suggestion, the heterodimer of ATF3/c-Jun can induce heat shock protein 27, which activates the Akt pathway and inhibits MEKK1-JNK, thereby suppressing apoptosis in neuronal cells.35 Therefore, apart from being a repressor in suppressing NF-κB-dependent inflammatory responses, ATF3 possibly activates transcription as a heterodimer; this effect on tissue damage induced by renal I/R would be of interest for future study.

In addition to the heteromeric complexity of ATF3, the factor has been shown to have a number of splice variants from different cellular contexts under various stimuli. For example, the isoforms ATF3ΔZip2a and ATF3ΔZip2b were isolated from cells treated with stimuli such as calcium ionophore A23187, TNF-α, endoplasmic reticulum stress, or oxidative stress36; other isoforms, such as ATF3ΔZip2c or ATF3ΔZip3, have also been reported.37 Because some of these splicing variants code for C-terminal deletion proteins and were found to counteract the transcriptional regulation by full-length ATF3 in a reporter assay,36 additional studies are needed to further clarify whether these alternatively spliced isoforms are indeed expressed and, if so, the functional roles they play under renal I/R conditions.

Of note, the kinetics of nuclear HDAC1 protein does not precisely parallel the overall status of H4 acetylation at the promoters of the IL-6 and IL-12b genes after renal I/R injury (Figure 8). This finding could be simply due to the promoter H4 acetylation status being determined by multiple histone acetyltransferase and HDAC activity. Similarly, we found the histone of the promoter regions of IL-6 and IL-12b genes hyperacetylated in ATF3-KO mice compared with WT mice, even under the basal condition (Figure 8F). However, the mechanism underlying these differences is currently elusive and requires further investigation.

Unlike pharmacologic studies involving nonselective HDAC inhibitors, such as trichostatin A, sodium butyrate, or valproic acid,7–9 our in vivo shRNA silencing experiments demonstrated, for the first time, the specific involvement of HDAC1 in ATF3-mediated epigenetic modification in response to renal I/R injury. At least 11 subtypes of HDACs that deacetylate histones have been described in mammals,38,39 so whether other HDAC isotypes (except HDAC3; Figure 8) also participate in I/R-induced, ATF3-dependent chromatin remodeling similarly to HDAC1 warrants further systematic and thorough investigation. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that some HDACs also deacetylate nonhistone proteins, such as α-tubulin, p53, MyoD, Stat3, or even the p65 subunit of NF-κB.40,41 Therefore, further exploration of whether deacetylation of these nonhistone targets plays a role in ATF3-mediated protection after I/R is of interest.

In summary, this study revealed a novel mechanism underlying the anti-inflammatory action of ATF3, which confers protection against I/R injury in the kidney. In addition, our data highlight the critical role of ATF3-mediated HDAC1 recruitment in epigenetic regulation of NF-κB-induced inflammatory gene expression after renal I/R. Thus, overexpression of ATF3, by gene delivery or recombinant protein infusion, or pharmacologic modulation of HDAC activity may be a viable strategy to prevent acute cell damage and improve the outcome of I/R injury to the kidney.

Concise Methods

Animal Model for Renal I/R

The ATF3-KO mice were kindly provided by Dr. Tsonwin Hai as described.27 The ATF3-KO allele was backcrossed into C57BL/6 for at least seven generations before renal I/R experiments. Male mice, 8 to 10 weeks old, underwent bilateral renal artery occlusion (45 minutes) and reperfusion for the indicated times.42 Sham operation was the identical surgery, except for pedicle clamping. All surgical procedures were performed according to the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee, Academia Sinica.

Western Blot Analysis

Kidney and cell extracts were separated on SDS-PAGE and underwent Western blot analysis by the protocol of an ECL kit (Pierce). Antibodies used were anti-ATF3 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-HDAC1 (1:1000; Millipore); anti-GST (1:1000), anti-NF-κB (1:500), and anti-IκBα (1:500; all Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-GAPDH (1:10,000; BD Pharmingen); anti-active caspase-3 (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology); anti-FLAG (1:1000; Sigma); and anti-β-actin (1:10,000; Millipore).

Histopathological Studies

Kidneys from all treated groups were fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight at 4°C and processed with paraffin fixation. Sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Apoptosis in renal tissues was identified by TUNEL assay with an in situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer's instructions. Infiltrating neutrophils were identified by positive staining for CD18 marker as described.43 In addition, myeloperoxidase, indicating neutrophil infiltration into tissue, was measured as described previously.44

Measurement of Biochemical Parameters

At the end of the reperfusion period, 500-μl blood samples were collected via the tail vein. Samples were centrifuged at 6000 × g for 3 minutes to separate the serum from the cells. Biochemical parameters were measured from serum within 24 hours.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the kidney by use of Trizol (Invitrogen). Real-time quantitative PCR analysis involved the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). For RT-PCR, total RNA was extracted from NRK-52E cells by use of Trizol; cDNA was prepared with the Super Script kit (Invitrogen) from 3 μg of total RNA with oligo(dT) for analysis. Primers used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Gene | Forward | Reverse | Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| mIL-6 | TCCAGTTGCCTTCTTGGGAC | GTGTAATTAAGCCTCCGACTTG | Q-PCR |

| mIL-12b | CAGAATCACAACCATCAGCAGATC | TGGCTGATAGGAGGAAGGCTTA | Q-PCR |

| GAPDH | GGAGCCAAACGGGTCATCATCTC | GAGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTCT | Q-PCR |

| Rat IL-6 | CTCTCCGCAAGAGACTTCCAG | GCCGAGTAGACCTCATAGTGA | RT-PCR |

| Rat IL-12b | TGGAGAAACGGTGACCCTCAC | GGCCTCCACCACCAGTTCAAT | RT-PCR |

| ATF3 | TTGGATCCATGATGCTTCAACAC | CCCAAGCTTTTACTTGTCATCGTC | RT-PCR |

| mIL-6 | TGCTCAAGTGCTGAGTCACT | AGACTCATGGGAAAATCCCA | ChIP |

| mIL-12b | GGAAAGGTGGCCCAGATACACTAGG | TAAGAAGTTCCTCCCTCCCCCCCTT | ChIP |

m, mouse; Q-PCR, quantitative PCR.

Nuclear Extracts and EMSA

We purchased NF-κB DNA probes containing a consensus NF-κB enhancer element (5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. EMSA analysis of nuclear NF-κB was performed as described.44 Briefly, nuclear extracts were prepared, and binding reactions were performed in 20-μl reaction mixtures with 3 μg of nuclear extracts. Reactions were loaded on a 5% polyacrylamide gel and run at 100 V at 4°C in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDAT buffer. The gel was dried and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (Molecular Dynamics).

Adenovirus Preparation and Gene Transfer

The procedure was as described previously.45 We constructed in the replication-defective recombinant adenoviral vector a human phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter to drive ATF3 expression (Ad:ATF3) and a PGK alone to serve as a control (Ad:PGK). Replication-defective recombinant adenoviral vectors were amplified and titrated in HEK-293 cells as described.45 For adenovirus-mediated gene transfer, cells were exposed to adenoviral vectors at the indicated multiplicity of infection.

In Vitro Hypoxia-Reoxygenation Experiments

One day after adenovirus infection, NRK-52E cells were incubated under conditions of normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2; pO2 = 8 mmHg) for 24 hours, followed by 12 or 24 hours of reoxygenation. After hypoxia-reoxygenation, the cells were lysed with use of NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Pierce), proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and levels were examined by Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies.

Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Protein Extraction

Cells and kidney tissues were extracted for nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions according to the manufacturer's protocol (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

ChIP Assay

After adenovirus infection, NRK-52E cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde, and ChIP assay involved the Upstate protocol (Millipore). Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma), anti-HDAC1 antibody (Abcam), and anti-acetyl H4 antibody (Millipore). The purified DNA was detected by standard PCR. Primers are listed in Table 1.

In Vivo HDAC Enzyme Assay

Nuclear extracts of kidney were prepared as described above, and the HDAC activity was measured by use of a HDAC colorimetric assay/drug discovery kit (Biomol).

Immunofluorescence

NRK-52E cells were cotransfected with pcDNA3-ATF3-FLAG and pcDNA4-mHDAC1-myc by use of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Two days after transfection, cells were incubated with mouse anti-FLAG (1:500; Sigma) and rabbit anti-myc antibodies (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The secondary antibodies were rhodamine red-linked anti-rabbit IgG (1:100) and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:100; both Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). Immunostained cells were examined under a Bio-Rad Radiance-2100 confocal immunofluorescence microscope.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Transfected cells were lysed in 100 μl of RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, and 5 mM EDTA) and centrifuged to remove cell debris. The cleared lysates then underwent immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-FLAG (Sigma) antibody. Protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham) were added and incubated for 2 hours. Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE. HDAC1 was immunoprecipitated and detected by Western blot analysis with mouse anti-HDAC1 antibody (1:1000; Millipore).

In Vitro Protein Synthesis and GST Pull-down Assay

The in vitro-translated product was processed by use of the T7 polymerase-based TNT quick coupled transcription/translation kit (Promega) and then incubated with GST fusion proteins in 1 ml of binding buffer (40 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 100 mM KCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, and 20 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) at 4°C for 4 hours, and the bound fraction was purified through glutathione-Sepharose beads (Pierce) at 4°C for 2 hours. The pull-down complexes were separated by SDS-10% PAGE and examined by Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies.

Production of shRNA in Lentiviral Vector

The TRCN0000039402 (shHDAC1) clone, pMD.G plasmid, and pCMVΔR8.91 plasmid were obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility at the Institute of Molecular Biology (Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan). The shHDAC1 clone encodes a small-interfering oligonucleotide specific for mouse HDAC1 gene. The production of lentivirus was according to National RNAi Core Facility's instructions.

Intrarenal Pelvic Injection of Recombinant AAV or Lentivirus

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and placed on a heating pad to maintain the core body temperature at 37°C; the left kidney was exposed via a flank incision. The left ureter was identified, and the left renal pelvis was then exposed. The renal artery, renal vein, and ureter were clamped at the same time just below the renal pelvis before transfection. Recombinant AAV, lentivirus, or PBS was slowly injected into the left renal artery with use of a 30-G needle. The tip of the needle was kept in the renal pelvis for 5 min to prevent the solution from leaking through the injected hole, then the needle was removed and the ureter was declamped. After 2 weeks, mice were euthanized, and kidneys were removed and homogenized.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences between groups were analyzed by unpaired t test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Taiwan University (grant 97R0066-43 to C.-F.C), the Institute of Biomedical Sciences (grant IBMS-CRC96-P01), Academia Sinica (grant AS-97-FP-L16), and the National Science Council (grant NSC97-2314-B-320-008 to H.L. or NSC97-2320-B-001-009-MY3, NSC98-2752-B-006-003-PAE, NSC98-2752-B-001-002-PAE to R.-B.Y). RNAi reagents were obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility located at the Institute of Molecular Biology/Genomic Research Center, Academia Sinica, supported by the National Research Program for Genomic Medicine Grants of the National Science Council (NSC 97-3112-B-001-016).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schiffl H, Lang SM, Fischer R: Daily hemodialysis and the outcome of acute renal failure. N Engl J Med 346: 305–310, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Star RA: Treatment of acute renal failure. Kidney Int 54: 1817–1831, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daemen MA, de Vries B, Buurman WA: Apoptosis and inflammation in renal reperfusion injury. Transplantation 73: 1693–1700, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kouzarides T: Acetylation: A regulatory modification to rival phosphorylation? EMBO J 19: 1176–1179, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheung P, Allis CD, Sassone-Corsi P: Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell 103: 263–271, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ren M, Leng Y, Jeong M, Leeds PR, Chuang DM: Valproic acid reduces brain damage induced by transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats: Potential roles of histone deacetylase inhibition and heat shock protein induction. J Neurochem 89: 1358–1367, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim HJ, Rowe M, Ren M, Hong JS, Chen PS, Chuang DM: Histone deacetylase inhibitors exhibit anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects in a rat permanent ischemic model of stroke: Multiple mechanisms of action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321: 892–901, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhao TC, Cheng G, Zhang LX, Tseng YT, Padbury JF: Inhibition of histone deacetylases triggers pharmacologic preconditioning effects against myocardial ischemic injury. Cardiovasc Res 76: 473–481, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Granger A, Abdullah I, Huebner F, Stout A, Wang T, Huebner T, Epstein JA, Gruber PJ: Histone deacetylase inhibition reduces myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. FASEB J 22: 3549–3560, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hai T, Hartman MG: The molecular biology and nomenclature of the activating transcription factor/cAMP responsive element binding family of transcription factors: activating transcription factor proteins and homeostasis. Gene 273: 1–11, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hai T, Wolfgang CD, Marsee DK, Allen AE, Sivaprasad U: ATF3 and stress responses. Gene Expr 7: 321–335, 1999. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allen-Jennings AE, Hartman MG, Kociba GJ, Hai T: The roles of ATF3 in liver dysfunction and the regulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene expression. J Biol Chem 277: 20020–20025, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yin T, Sandhu G, Wolfgang CD, Burrier A, Webb RL, Rigel DF, Hai T, Whelan J: Tissue-specific pattern of stress kinase activation in ischemic/reperfused heart and kidney. J Biol Chem 272: 19943–19950, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haber BA, Mohn KL, Diamond RH, Taub R: Induction patterns of 70 genes during nine days after hepatectomy define the temporal course of liver regeneration. J Clin Invest 91: 1319–1326, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilchrist M, Thorsson V, Li B, Rust AG, Korb M, Roach JC, Kennedy K, Hai T, Bolouri H, Aderem A: Systems biology approaches identify ATF3 as a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature 441: 173–178, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilchrist M, Henderson WR, Jr., Clark AE, Simmons RM, Ye X, Smith KD, Aderem A: Activating transcription factor 3 is a negative regulator of allergic pulmonary inflammation. J Exp Med 205: 2349–2357, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yoshida T, Sugiura H, Mitobe M, Tsuchiya K, Shirota S, Nishimura S, Shiohira S, Ito H, Nobori K, Gullans SR, Akiba T, Nitta K: ATF3 protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 217–224, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dragun D, Tullius SG, Park JK, Maasch C, Lukitsch I, Lippoldt A, Gross V, Luft FC, Haller H: ICAM-1 antisense oligodesoxynucleotides prevent reperfusion injury and enhance immediate graft function in renal transplantation. Kidney Int 54: 590–602, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singbartl K, Ley K: Protection from ischemia-reperfusion induced severe acute renal failure by blocking E-selectin. Crit Care Med 28: 2507–2514, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kielar ML, John R, Bennett M, Richardson JA, Shelton JM, Chen L, Jeyarajah DR, Zhou XJ, Zhou H, Chiquett B, Nagami GT, Lu CY: Maladaptive role of IL-6 in ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3315–3325, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singbartl K, Green SA, Ley K: Blocking P-selectin protects from ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute renal failure. FASEB J 14: 48–54, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barnes PJ: Nuclear factor-kappa B. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 29: 867–870, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pan J, Xia L, Yao L, McEver RP: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha- or lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of the murine P-selectin gene in endothelial cells involves novel kappaB sites and a variant activating transcription factor/cAMP response element. J Biol Chem 273: 10068–10077, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Plaisance S, Vanden Berghe W, Boone E, Fiers W, Haegeman G: Recombination signal sequence binding protein Jkappa is constitutively bound to the NF-kappaB site of the interleukin-6 promoter and acts as a negative regulatory factor. Mol Cell Biol 17: 3733–3743, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ashburner BP, Westerheide SD, Baldwin AS, Jr.: The p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-kappaB interacts with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) corepressors HDAC1 and HDAC2 to negatively regulate gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 21: 7065–7077, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hua B, Tamamori-Adachi M, Luo Y, Tamura K, Morioka M, Fukuda M, Tanaka Y, Kitajima S: A splice variant of stress response gene ATF3 counteracts NF-kappaB-dependent anti-apoptosis through inhibiting recruitment of CREB-binding protein/p300 coactivator. J Biol Chem 281: 1620–1629, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hartman MG, Lu D, Kim ML, Kociba GJ, Shukri T, Buteau J, Wang X, Frankel WL, Guttridge D, Prentki M, Grey ST, Ron D, Hai T: Role for activating transcription factor 3 in stress-induced beta-cell apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 24: 5721–5732, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu D, Wolfgang CD, Hai T: Activating transcription factor 3, a stress-inducible gene, suppresses Ras-stimulated tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem 281: 10473–10481, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang C, Kawauchi J, Adachi MT, Hashimoto Y, Oshiro S, Aso T, Kitajima S: Activation of JNK and transcriptional repressor ATF3/LRF1 through the IRE1/TRAF2 pathway is implicated in human vascular endothelial cell death by homocysteine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 289: 718–724, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang Q, Mora-Jensen H, Weniger MA, Perez-Galan P, Wolford C, Hai T, Ron D, Chen W, Trenkle W, Wiestner A, Ye Y: ERAD inhibitors integrate ER stress with an epigenetic mechanism to activate BH3-only protein NOXA in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 2200–2205, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ohba N, Maeda M, Nakagomi S, Muraoka M, Kiyama H: Biphasic expression of activating transcription factor-3 in neurons after cerebral infarction. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 115: 147–156, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen BP, Liang G, Whelan J, Hai T: ATF3 and ATF3 delta Zip. Transcriptional repression versus activation by alternatively spliced isoforms. J Biol Chem 269: 15819–15826, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wolfgang CD, Chen BP, Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ, Hai T: gadd153/Chop10, a potential target gene of the transcriptional repressor ATF3. Mol Cell Biol 17: 6700–6707, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hsu JC, Bravo R, Taub R: Interactions among LRF-1, JunB, c-Jun, and c-Fos define a regulatory program in the G1 phase of liver regeneration. Mol Cell Biol 12: 4654–4665, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nakagomi S, Suzuki Y, Namikawa K, Kiryu-Seo S, Kiyama H: Expression of the activating transcription factor 3 prevents c-Jun N-terminal kinase-induced neuronal death by promoting heat shock protein 27 expression and Akt activation. J Neurosci 23: 5187–5196, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hashimoto Y, Zhang C, Kawauchi J, Imoto I, Adachi MT, Inazawa J, Amagasa T, Hai T, Kitajima S: An alternatively spliced isoform of transcriptional repressor ATF3 and its induction by stress stimuli. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 2398–2406, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pan Y, Chen H, Siu F, Kilberg MS: Amino acid deprivation and endoplasmic reticulum stress induce expression of multiple activating transcription factor-3 mRNA species that, when overexpressed in HepG2 cells, modulate transcription by the human asparagine synthetase promoter. J Biol Chem 278: 38402–38412, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thiagalingam S, Cheng KH, Lee HJ, Mineva N, Thiagalingam A, Ponte JF: Histone deacetylases: Unique players in shaping the epigenetic histone code. Ann N Y Acad Sci 983: 84–100, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. de Ruijter AJ, van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, van Kuilenburg AB: Histone deacetylases (HDACs): Characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem J 370: 737–749, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dai Y, Rahmani M, Dent P, Grant S: Blockade of histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced RelA/p65 acetylation and NF-kappaB activation potentiates apoptosis in leukemia cells through a process mediated by oxidative damage, XIAP downregulation, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 activation. Mol Cell Biol 25: 5429–5444, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu Y, Smith PW, Jones DR: Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 functions as a corepressor by enhancing histone deacetylase 1-mediated deacetylation of RelA/p65 and promoting apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 26: 8683–8696, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patel NS, Chatterjee PK, Di Paola R, Mazzon E, Britti D, De Sarro A, Cuzzocrea S, Thiemermann C: Endogenous interleukin-6 enhances the renal injury, dysfunction, and inflammation caused by ischemia/reperfusion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312: 1170–1178, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. De Clerck LS, De Gendt CM, Bridts CH, Van Osselaer N, Stevens WJ: Expression of neutrophil activation markers and neutrophil adhesion to chondrocytes in rheumatoid arthritis patients: Relationship with disease activity. Res Immunol 146: 81–87, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin H, Cheng CF, Hou HH, Lian WS, Chao YC, Ciou YY, Djoko B, Tsai MT, Cheng CJ, Yang RB: Disruption of guanylyl cyclase-G protects against acute renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 339–348, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin H, Lin TN, Cheung WM, Nian GM, Tseng PH, Chen SF, Chen JJ, Shyue SK, Liou JY, Wu CW, Wu KK: Cyclooxygenase-1 and bicistronic cyclooxygenase-1/prostacyclin synthase gene transfer protect against ischemic cerebral infarction. Circulation 105: 1962–1969, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.