Abstract

Butyrate is an inhibitor of histone deacetylase (HDAC) and has been extensively evaluated as a chemoprevention agent for colon cancer. We recently demonstrated that mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene confer resistance to HDAC inhibitor-induced apoptosis in colon cancers (Huang and Guo, Cancer Research, 66(18), 9245-9251, 2006). Here we show that APC mutation rendered colon cancer cells resistant to butyrate-induced apoptosis due to the failure of butyrate to down-regulate survivin in these cells. Another cancer preventive agent, 3,3′-Diindolylmethane (DIM), was identified to be able to down-regulate survivin in colon cancers expressing mutant APC. DIM inhibited survivin mRNA expression and promoted survivin protein degradation through inhibition of p34cdc2-cyclin B1-mediated survivin Thr34 phosphorylation. Pre-treatment with DIM enhanced butyrate-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells expressing mutant APC. DIM/butyrate combination treatment induced the expression of pro-apoptotic Bax and Bak proteins, triggered Bax dimerization/activation, and caused release of cytochrome c and Smac proteins from mitochondria. While overexpression of survivin blocked DIM/butyrate-induced apoptosis, knocking-down of survivin by siRNA increased butyrate-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. We further demonstrated that DIM was able to down-regulate survivin and enhance the effects of butyrate in apoptosis induction and prevention of familial adenomatous polyposis in APCmin/+ mice. Thus, the combination of DIM and butyrate is potentially an effective strategy for the prevention of colon cancer.

Keywords: 3,3′-Diindolylmethane; Butyrate; Survivin; Apoptosis; Adenomatous Polyposis Coli

Introduction

Colon cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer death in developed countries. A large number of pre-clinical studies have examined various agents for the prevention of colon cancer. However, significant tumor suppression activity was rarely observed, and tumor occurrence even increased after treatment in certain cases 1,2. Butyrate is produced naturally in the colon by bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers and has been extensively studied in colon cancer prevention. Butyrate inhibits tumor growth and induces apoptosis through the inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDAC) 3,4. Histone deacetylases together with histone acetyltransferases regulate the acetylation of core nucleosomal histones, which is important for the transcription activity of the target genes 5. Abnormal HDAC activity has been associated with the development of many types of cancer 6. HDAC inhibitors induce differentiation, growth arrest, and apoptosis in cancer cells, while they are relatively nontoxic to normal cells 6-8. As an HDAC inhibitor, butyrate is a promising prevention agent for colon cancer 9,10. However, the activity of butyrate has been moderate in chemoprevention studies using animal models 11-13. For a potential explanation of the ineffectiveness of butyrate, we recently demonstrated that mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene in colon cancers can confer resistance to HDAC inhibitor-induced apoptosis 14.

Colon cancer is caused by the accumulation of mutations in a number of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. APC, deleted in colon cancer (DCC), K-Ras, and p53 are among the most frequently mutated genes in colon cancer 15-18. APC is a key component of the β-catenin destruction complex (consisting GSK-3β, axin, and APC) and involved in the Wnt signaling pathway 19. Axin and APC form a structural scaffold that allows GSK-3β to phosphorylate β-catenin. Phosphorylated β-catenin is subsequently degraded by the proteasome 19. Loss of wild-type APC expression results in the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, which interacts with Tcf-4/Lef1 transcription factors to cause aberrant gene transcription and formation of cancer 20,21. The role of APC as a tumor suppressor has been further demonstrated in mice with APC mutations which develop multiple intestinal neoplasia (APCmin/+ mice) 22,23.

Previous studies in our lab have shown that resistance to HDAC inhibitors by colon cancers expressing mutant APC was due to a failure to down-regulate survivin 14. Survivin is an anti-apoptotic protein of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family. Survivin is expressed at high level in many types of cancers, but not in normal tissues from the same organs 24. Survivin blocks apoptosis by inhibiting caspases and antagonizing mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis 24. Survivin also regulates cell division through interaction with INCENP and Aurora B kinase 25.

3,3′-Diindolylmethane (DIM) is a non-toxic cancer-preventive phytonutrient isolated from broccoli and cabbage. The anti-cancer activity of DIM was linked with inhibition of mitochondrial H(+)-ATP synthase and induction of p21(Cip1/Waf1) expression in breast cancer cells 26, down-regulation of androgen receptor 27 and inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) 28 in prostate cancer cells, inhibition of AKT signaling and FLICE-like inhibitory protein in cholangiocarcinoma cells 29, activation of caspase-8 in colon cancer cells 30, as well as inactivation of NF-kappaB 31 and down-regulation of survivin in breast cancer cells 32. DIM was also shown to inhibit angiogenesis and invasion by repressing the expression of matrix metalloproteinase MMP-9 and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) 33.

In the present study, we found that colon cancer cells expressing mutant APC are resistant to butyrate-induced apoptosis due to the failure to down-regulate survivin. Importantly, we shown that DIM was able to down-regulate survivin and potentiate butyrate-induced apoptosis in these resistant cells. DIM can be used to enhance the efficacy of butyrate in colon cancer prevention.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Transfection

Human colon cancer cell line HT-29 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Human colon cancer HT-29/APC and HT-29/β-Gal cells were generously provided by Dr. Vogelstein of Johns Hopkins University and cultured as described 34. IMCE cells were kindly provided by Dr. Robert H. Whitehead of Vanderbilt University and cultured at 33°C, in RPMI1640 media containing 5% fetal calf serum, 1 μg/ml insulin, 10-5M α-thioglycerol and 5 units/ml of mouse gamma interferon. For transient transfection, plasmids were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine™Plus Reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Drugs and Chemicals

Butyrate was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at concentration of 400 mM. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane was purchased from LKT Laboratories (St. Paul, MN) and dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at concentration of 40 mM. In all studies, an equivalent amount of diluent (DMSO or PBS) was added to culture media as a negative control. Proteasome inhibitor MG-132 was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA) and dissolved in DMSO at concentration of 10 mM. Cycloheximide was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in DMSO at concentration of 355 mM. Disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Plasmids Construction

Human cDNA encoding full-length survivin gene was obtained by PCR amplification using an EST clone (I.M.A.G.E. clone ID 4477581) as template. Survivin cDNA was sub-cloned into phrGFP-C and pCMV-Tag2A expression vectors (Stratagene).

Detection of Apoptosis

In TUNEL assay, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde on ice for 1h and then washed with PBS and permeabilized with 70% ethanol at -20 °C for 12h. Cells were then labeled with Guava® TUNEL Assay reagents and analyzed on the Guava PCA microcytometer following the manufacturer's protocol. In 4′,6-diamidine-29-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) staining, GFP or GFP-survivin expressing cells were fixed with PBS containing 3.7% formaldehyde, and stained with 0.5 μg/ml DAPI in PBS. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined by confocal microscopy, counting GFP-positive cells having nuclear fragmentation and/or chromatin condensation. In the Elisa assay, the Cell Death Detection ElisaPLUS kit (Roche) was used following the manufacturer's protocol. This assay determines apoptosis by measuring mono- and oligonucleosomes in the lysates of apoptotic cells. The cell lysates were placed into a streptavidin-coated microplate and incubated with a mixture of anti-histone-biotin and anti-DNA-peroxidase. The amount of peroxidase retained in the immunocomplex was photometrically determined with ABTS as the substrate. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS in PBS). Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) was added to lysis buffer before use. Protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad DC protein assay (Bio-Rad). Protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked in 5% non-fat milk in PBS overnight and incubated with primary antibody and subsequently with appropriate horse radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Signals were developed with ECL reagents (Amersham) and exposure to X-ray films. Image digitization and quantification were performed with UN-SCAN-IT software from Silk Scientific (Orem, UT). Anti-survivin, anti-Cdc2, anti-Cyclin B1, anti-Bax, and anti-β-tubulin monoclonal antibodies, and anti-Bak polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-hrGFP monoclonal antibody was purchased from Stratagene. Anti-Smac monoclonal antibody and anti-cleaved caspase-3, anti-cleaved caspase-7, anti-cleaved caspase-9, anti-HDAC1, anti-HDAC2, anti-HDAC3, anti-HDAC4, anti-HDAC5, anti-HDAC7, and anti-cleaved PARP polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-phospho-survivin (Thr34) polyclonal antibody was purchased from Novus. Anti-Hsp60 monoclonal antibody was purchase from BD Biosciences. APC protein was detected by western blot as described previously 14. Anti-APC monoclonal antibody was purchased from Calbiochem.

Cross-linking Study

DSS was dissolved in DMSO at 25 mM concentration. Before protein isolation for western blot, cells were treated with 1 mM DSS in PBS for 30 min at 37°C. The stop solution (1 M Tris, pH 7.5) was then added to a final concentration of 10 mM and incubated for 15 min. Total protein was isolated and western blot was performed as described above.

Subcellular Fractionation

Cells (20 × 106) were harvested by centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellets were washed once with ice-cold PBS and resuspended with 5 volumes of buffer A (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCI, 1.5 mM MgCI2, 1 mM sodium EDTA, 1 mM sodium EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride) containing 250 mM sucrose. Cells were homogenized with 10 strokes of a Teflon homogenizer, and centrifuged twice at 750 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting mitochondria pellets were resuspended in buffer A and frozen at -80°C for future use. The supernatants of the 10,000 × g spin were further centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C, and the resulting supernatants were designated cytosol fraction and stored at -80°C.

siRNAs and Transfection

Silencer™ validated siRNAs and negative control siRNA (Cat# 4611) were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). The sequence for survivin siRNA is: sense (5′-GGAACAUAAAAAGCAUUCGtt-3′) and antisense (5′-CGAAUGCUUUUUAUGUUCCTC -3′). Survivin siRNA was transfected into HT-29 cells using X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent (Roche) following the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were cultures and transfected in 6-well plates (1×105 cells per well) and the final siRNA concentration was 100 nM. Protein samples were collected at 48h after transfection for western blot analysis. For apoptosis assay, drugs were added at 24h after siRNA transfection and cells were collected at 72h post transfection.

Real-time PCR

The mRNA level of survivin was measure by real-time PCR using TaqMan® Gene Expression assay (Cat # Hs00153353) from Applied Biosystems (Foster city, CA). Total RNA was isolated from HT-29 cells using RNeasy® kit (Qiagen). 5 μg of total RNA was used in reverse transcription reaction. The cDNAs were used as templates to perform PCR on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-time PCR System following the manufacturer's protocol.

APCmin/+ Mice and Treatment

APCmin/+ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed in an animal-holding room under controlled light, temperature and humidity and were fed Purina lab rodent diet (LabDiet 5K20) and water ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of North Dakota State University. For treatment, APCmin/+ mice were separated into four groups (5 each): control group, butyrate group, DIM group, and DIM/butyrate combination group. Treatment began at six weeks of age. For DIM and DIM/butyrate group, DIM was administered in drinking water at a calculated dose of 10 mg/kg/day on days 1, 3, and 5 during week six. Butyrate was administered in drinking water for one week, at a calculated dose of 24 mg daily, starting on day 1 of week six for the butyrate group and on day 7 of week six for the DIM/butyrate group. Calculation of the doses was done as shown in the following example: a 20 gram mouse drinks about 3ml water per day 35; 10 mg/kg equals to a dose of 0.067 mg/ml of DIM in water. Mice in the control group were treated with regular water. The mice were weighed twice weekly and monitored daily for signs of weight loss or lethargy that might indicate intestinal obstruction or anemia. At 16 weeks of age, Mice were euthanized by pentobarbital injection (200 mg/kg) and cervical dislocation. After necropsy, the intestinal tracts were dissected from the esophagus to the distal rectum, spread onto filter paper, opened longitudinally with fine scissors, and cleaned with sterile saline. Tumor counts were performed under a dissection microscope with ×5 magnification. For in vivo apoptosis detection, separate groups of mice were treated with doses and schedule as above and sacrificed at 24 hours after the last dose of treatments and the tumor specimens were fixed in formalin.

In vivo Apoptosis Detection

The apoptotic cells in tumors were detected using an ApopTag In situ Apoptosis Detection kit (Chemicon). The assay was done according to the manufacturer's protocol. Tumor were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. After deparaffinization, the tissue sections were pretreated with proteinase K and then incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzyme at 37°C for 1 h, washed thrice with PBS, and incubated with antidigoxigenin conjugate in a humidified chamber at room temperature for 30 min. The color was developed by incubating the sections with peroxidase substrate. Apoptosis indices were calculated as the percentage of apoptotic cells among 1000 tumor cells in a randomly selected nonnecrotic portion of the tumor.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between the mean values were analyzed for significance using the unpaired two-tailed Student's test for independent samples; P ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

APC mutation causes failure of survivin down-regulation and confers resistance to butyrate-induced apoptosis

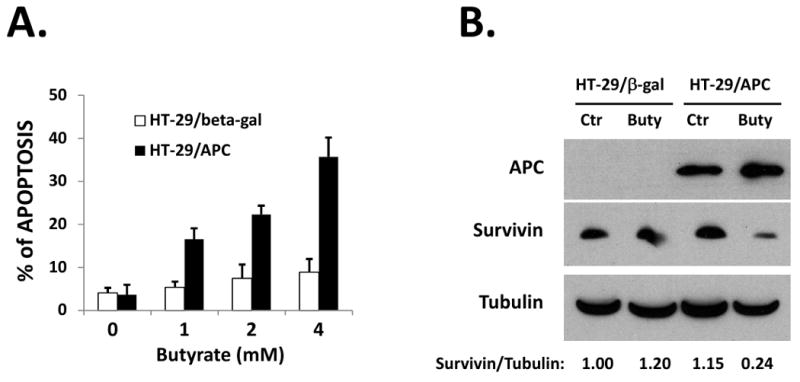

Butyrate has been extensively studied as a cancer prevention agent for colon cancers, but with only limited activity observed 11-13. We have previously shown that mutations in the APC gene (which occur in over 85% of sporadic colon cancers) render colon cancer cells resistant to HDAC inhibitors 14. Since butyrate acts as a HDAC inhibitor, we hypothesize that APC mutations may also cause resistance to butyrate-induced apoptosis. To determine whether APC plays a role in colon cancer cell apoptosis in response to butyrate, we compared butyrate-induced apoptosis in HT-29/β-Gal and HT-29/APC cells. HT-29 colon cancer cells express two C-terminal-truncated mutant APC proteins. HT-29/APC are genetically engineered HT-29 cells in which wild-type APC is expressed from a Zn2+-inducible transgene 34. Expression of APC induces apoptosis in HT-29 cells 34. To avoid apoptosis induce by APC expression alone, we used 50 μM Zinc to induce APC expression 14. After induction of wild-type APC, apoptosis was observed in HT-29/APC cells when treated with butyrate (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the HT-29/β-Gal cells were resistant. When Zn2+ was not added to the culture media to induce APC expression, HT-29/APC cells showed comparable resistance to butyrate-induced apoptosis (data not shown). We have previously demonstrated that a failure to down-regulate survivin is the key mechanism of APC mutation-induced resistance to HDAC inhibitors 14. To further understand the mechanism of APC-mediated apoptosis after butyrate treatment, we examined the expression of survivin. Down-regulation of survivin was observed in HT-29/APC cells after induction of APC expression and treatment with butyrate, but not in HT-29/β-Gal cells (Fig. 1B). Since HT-29 cell lines express mutant p53 proteins, the down-regulation of survivin appears to be p53-independent.

Figure 1. Butyrate down-regulates survivin and induces apoptosis in HT-29/APC cells, but not in HT-29/β-Gal cells.

(A) Butyrate induced apoptosis in HT-29/APC cells but not in HT-29/β-Gal cells. Cells were cultured in media containing 50 μM Zinc for 24h and then treated with various doses of butyrate for 24h. Apoptosis was analyzed by TUNEL assay. (B) Butyrate down-regulated survivin in HT-29/APC cells. HT-29/APC and HT-29/β-Gal cells were cultured in media containing 50 μM ZnCl2 for 24h and then treated with 2 mM butyrate for 24h. APC expression, survivin and β-Tubulin protein levels were detected by western blotting. Relative protein levels were quantified and shown under the gel. The experiments were repeated three times.

3,3′-Diindolylmethane down-regulates survivin in HT-29 cell

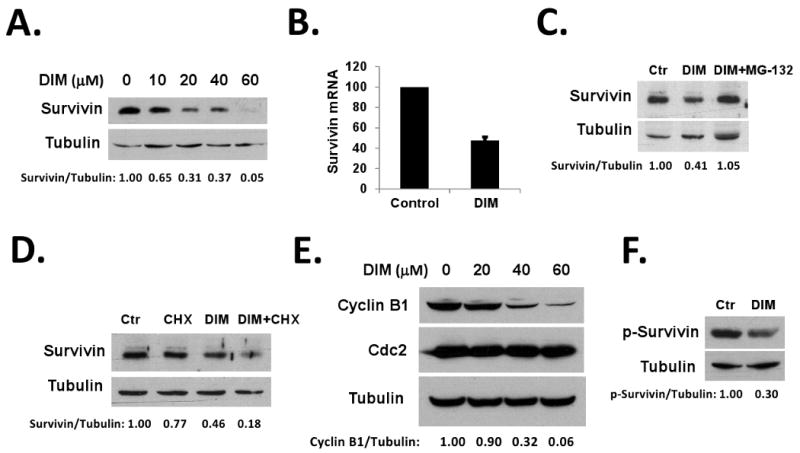

Since APC is frequently mutated in colon cancer patients, the data above predicts the ineffectiveness of butyrate in preventing colon cancers. To overcome resistance to butyrate-induced apoptosis in APC mutant tumors, we tested various agents (including Genistein, selenium, DIM, and others) to identify a non-toxic agent that can down-regulate survivin. We found that DIM, a cancer prevention agent from food plants including cabbage and broccoli, was able to down-regulate survivin in HT-29 cells. Treatment with DIM down-regulated survivin in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A). We determined whether down-regulation of survivin by DIM occurred at transcription level. Using real-time PCR, we found that treatment with 40 μM DIM for 24 hours decreased survivin mRNA level by 53% in HT-29 cells, compared to untreated cells (Figure 2B). Next, we determined whether proteasome-dependent degradation is also involved in the down-regulation of survivin in response to DIM. As shown in Figure 2C, co-treatment with a proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (10 μM) completely blocked the DIM-induced down-regulation of survivin protein in HT-29 cells. To determine if DIM promotes the degradation of survivin protein, HT-29 cells were treated with 20 μM cycloheximide or 20 μM cycloheximide plus 40 μM DIM, degradation of survivin was determined by western blotting. DIM exposure promoted survivin degradation in HT-29 cells (Figure 2D). The stability of survivin protein is maintained by p34cdc2-cyclin B1 phosphorylation on Thr34 of the protein, and Thr34 dephosphorylation causes survivin degradation 36,37. To further determine the mechanism of DIM-promoted survivin degradation, we examined the effects of DIM on p34cdc2 and cyclin B1. As shown in Figure 2E, DIM treatment caused a significant decrease of cyclin B1 protein level in a dose-dependent manner, while the p34cdc2 level remained unchanged. As a result, survivin Thr34 phosphorylation was decreased after DIM treatment (Figure 2F), contributing to the decreased stability of survivin. This result indicates that DIM causes survivin degradation independent of wild-type APC, through a mechanism involving decreased survivin Thr34 phosphorylation by p34cdc2-cyclin B1.

Figure 2. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane down-regulates survivin in HT-29 cells.

(A) DIM down-regulated survivin in HT-29 cells. HT-29 cells were treated with various doses of DIM for 24h. Survivin and β-Tubulin protein levels were detected by western blotting. (B) DIM inhibited transcription of survivin mRNA. HT-29 cells were treated with DMSO or 40 μM DIM for 24h. Total RNA was isolated from cells and analyzed by real-time PCR as described in Materials and Methods. (C) MG-132 blocked DIM-induced down-regulation of survivin. HT-29 cells were treated with DMSO, 40 μM DIM, or 40 μM DIM plus 2 μM MG-132 for 24h. Survivin and β-Tubulin protein levels were detected by western blotting. (D) HT-29 cells were treated with DMSO, 40 μM DIM for 24h, 20 μM cycloheximide for 2h, or 40 μM DIM for 22h plus 20 μM cycloheximide for additional 2h. Survivin and β-Tubulin protein levels were detected by western blotting. (E) DIM down-regulated cyclin B1. HT-29 cells were treated with various doses of DIM for 24h. Cyclin B1, cdc2, and tubulin protein levels were detected by western blotting. (F) DIM inhibited survivin Thr34 phosphorylation. HT-29 cells were transfected with pCMV-Tag2A-survivin plasmids. 24h after transfection, cells were treated with 40 μM DIM together with 10 μM MG-132 (to prevent protein degradation) for additional 24h. p-Thr34-survivin and tubulin levels were detected by western blotting. Relative protein levels were quantified and shown under the gels. All experiments were repeated three times.

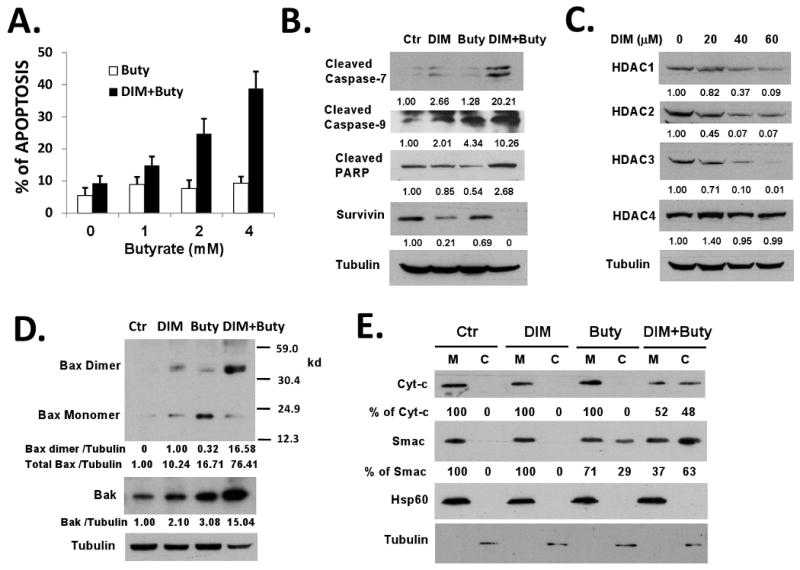

3,3′-Diindolylmethane enhances butyrate-induced apoptosis in HT-29 cells

Since DIM is able to down-regulate survivin in HT-29 cells, we tested whether DIM can help overcome APC mutation-mediated resistance to butyrate-induced apoptosis. Pre-treatment with 40 μM DIM significantly enhanced butyrate-induced apoptosis in HT-29 cells (Figure 3A). DIM alone at this dose did not induce significant level of apoptosis. To identify the key mediators of DIM/butyrate-induced apoptosis, HT-29 cells were treated with DIM, butyrate, or DIM/butyrate combination. Western blot analysis with various antibodies identified significantly higher levels of cleaved (activated) caspase-7 and cleaved (activated) caspase-9 in DIM/butyrate-treated cells (Figure 3B), indicating these two caspases potentially mediate apoptosis in the combination treatment. We did not observe caspase-3 activation in these treatments (data not shown). Interestingly, the combination of DIM and butyrate was synergistic in causing survivin down-regulation (Figure 3B). We also determined the effects of DIM on the expression level of HDAC proteins in HT-29 cells. As shown in Figure 3C, DIM treatment induced significant decreases in the levels of class I HDACs (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3) in a dose-dependent manner. However, DIM had no effects on the levels of class II HDACs (HDAC4, HDAC5, and HDAC7) (Figure 3C and data not shown). By down-regulating the HDAC proteins, DIM should enhance the effects of butyrate on HDAC inhibition. To further understand the mechanisms of how DIM increases butyrate-induced apoptosis in HT-29 cells, we examined the effects of DIM/butyrate combination on the key apoptosis regulators Bax and Bak. Bax and Bak double knockout mice displayed developmental defects in multiple tissues, indicating that Bax and Bak are critical apoptosis regulators 38. Deletion of both Bax and Bak also results in resistance to various apoptotic stimuli known to trigger mitochondria-dependent apoptosis 39. In contrast, the BH3-only proteins of the Bcl-2 family (Bid, Bad etc.) are signal transducers and they require Bax or Bak to induce apoptosis 39,40. We found that the DIM/butyrate combination treatment caused significant increases of both Bax and Bak proteins, as well as the dimerization of the 21 kd monomer Bax into 42 kd dimers (representing the activated Bax, 41,42) (Figure 3D). Activation of Bax and Bak may facilitate or directly cause the release of pro-apoptotic mitochondrial proteins into cytosol. To test this hypothesis, the localization of cytochrome c and Smac proteins was determined by subcellular fractionation experiments. As shown in Figure 3E, the DIM/butyrate combination caused significant release of cytochrome c and Smac proteins from the mitochondria of HT-29 cells. Cytochrome c together with Apaf-1 promote apoptosome formation and activation of pro-caspase-9 43,44 while Smac antagonizes the activities of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) and activates caspases 45, which explain the observed activation of caspases and apoptosis in HT-29 cells (Figure 3A and 3B).

Figure 3. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane enhances butyrate-induced apoptosis in HT-29 cells.

(A) DIM enhanced butyrate-induced apoptosis in HT-29 cells. HT-29 cells were treated with or without 40 μM DIM for 24h and then treated with various doses of butyrate for additional 24 hours. Apoptosis was analyzed by TUNEL assay. (B) DIM/butyrate combination activated caspase-7 and caspase-9 and down-regulated survivin. HT-29 cells were treated with DMSO (control), 40 μM DIM, 2 mM butyrate for 24h, or 40 μM DIM for 24h followed by 2 mM butyrate for additional 24h. Protein lysates were analyzed by western blotting. (C) DIM down-regulated HDAC proteins in HT-29 cells. HT-29 cells were treated with various doses of DIM for 24h. HDAC and β-Tubulin protein levels were detected by western blotting. (D) DIM/butyrate treatment induced Bax and Bak expression and Bax activation. HT-29 cells were treated as described in (B). Protein lysates were analyzed by western blotting. Bax dimerization was detected by cross-linking experiments as described in Materials and Methods. (E) DIM/butyrate caused release of cytochrome c and Smac from mitochondria in HT-29 cells. HT-29 cells were treated as described in (B). Cytosolic (C) and mitochondrial (M) fractions of cells were isolated by differential centrifugation as described in Materials and Methods. Localization of cytochrome c and Smac in the fractions was detected by western blot. Relative protein levels were quantified and shown under the gels. All experiments were repeated three times.

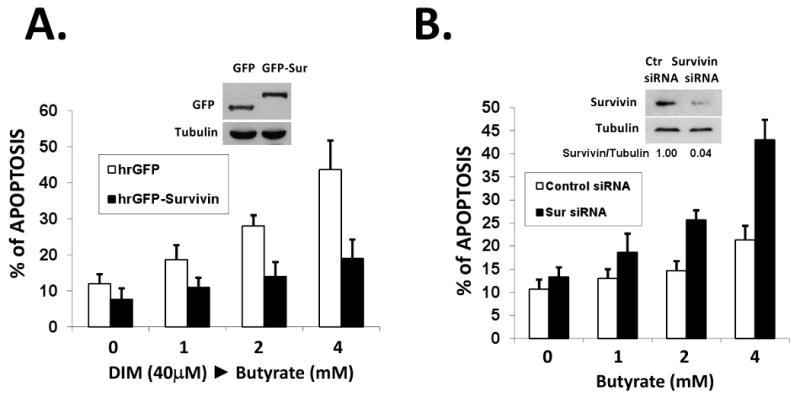

Survivin plays a key role in DIM/butyrate-induced apoptosis

We understand that survivin is not the only target of DIM. However, survivin may play a key role in the apoptotic effects observed during DIM/butyrate combination treatment. To determine the role of survivin, we overexpressed survivin protein in HT-29 cells by transient transfection. As shown in Figure 4A, overexpression of survivin blocked DIM/butyrate-induced apoptosis in HT-29 cells. Furthermore, knocking-down survivin by siRNA sensitized HT-29 cells to butyrate-induced apoptosis (Figure 4B). These data suggest that despite survivin is not the only target of DIM, it plays a critical role in DIM's activity when in combination with butyrate. Down-regulation of survivin by DIM lowers the threshold of apoptosis induction and allows the activation of downstream mechanisms of apoptosis (such as Bax activation, cytochrome c / Smac release, and activation of caspases).

Figure 4. Survivin plays a key role in DIM/butyrate-induced apoptosis.

(A) Overexpression of survivin blocked DIM/butyrate-induced apoptosis. HT-29 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of phrGFP or phrGFP-survivin vectors in 6-well plates. 24h after transfection, cells were treated with 40 μM DIM for 24h followed by various concentrations of butyrate for 24h. Expression of hrGFP-survivin was confirmed by western blotting with anti-hrGFP antibody. Apoptosis was analyzed by DAPI staining as described in Materials and Methods. The average result from three independent experiments was shown. (B) Knocking-down of survivin by siRNA sensitized HT-29 cells to butyrate-induced apoptosis. Survivin targeting siRNA and negative control siRNA were transfected into HT-29 cells as described in Materials and Methods. Down-regulation of survivin was confirmed by western blotting of protein samples collected at 48h after transfection. At 24h post siRNA transfection, various concentrations of butyrate were added to cells and apoptosis was analyzed 24h after butyrate exposure by TUNEL assay. The average result from three independent experiments was shown.

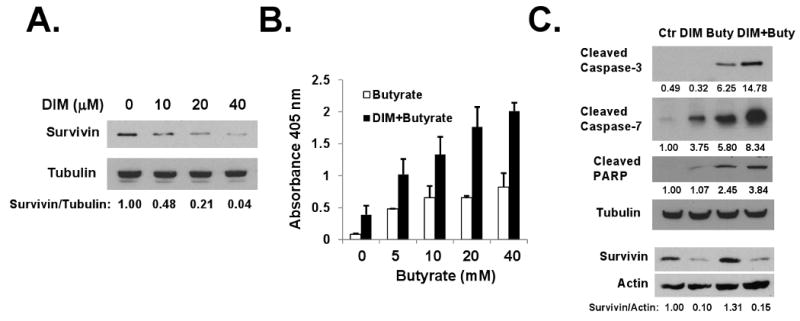

3,3′-Diindolylmethane down-regulates survivin and enhances butyrate-induced apoptosis in IMCE cells

To determine whether DIM can be effective when used in combination with butyrate for in vivo cancer prevention using APCmin/+ mice, we examined the effects of DIM/butyrate combination in IMCE cells. IMCE cells are colon epithelial cells derived from APCmin/+ mice, a mouse model widely used in colon cancer prevention research 46. As shown in Figure 5A and 5B, DIM was able to down-regulate survivin in IMCE cells and significantly enhance butyrate-induce apoptosis in these cells. Comparing to HT-29 cells, caspase-3 and caspase-7 were activated by DIM/butyrate combination treatment in IMCE cells (Figure 5C), and potentially mediated apoptosis in these cells. We did not observe caspase-9 activation in these cells (data not shown). The different profiles of caspase activation between IMCE and HT-29 cells could be due to the different genetics of human and mouse cells. Thus, different caspases may mediate apoptosis between HT-29 and IMCE cells. Comparing to DIM-only treatment, the combination of DIM/butyrate did not further reduce the level of survivin protein (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane down-regulates survivin and enhances butyrate-induced apoptosis in IMCE cells.

(A) DIM down-regulated survivin in IMCE cells. IMCE cells were treated with various doses of DIM for 48h. Survivin and β-Tubulin protein levels were detected by western blotting. (B) DIM enhanced butyrate-induced apoptosis in IMCE cells. IMCE cells were treated with 40 μM DIM for 24h and then treated with various doses of butyrate for additional 24 hours. Apoptosis was analyzed using the Cell Death Detection ElisaPLUS kit as described in Materials and Methods. The average results from three independent experiments were shown. (C) Caspse-3 and caspase-7 mediated DIM/butyrate-induced apoptosis. IMCE cells were treated with DMSO (control), 40 μM DIM, 40 mM butyrate for 24h, or 40 μM DIM for 24h followed by 40 mM butyrate for additional 24h. Protein lysates were analyzed by western blotting. Relative protein levels were quantified and shown under the gels. All experiments were repeated three times.

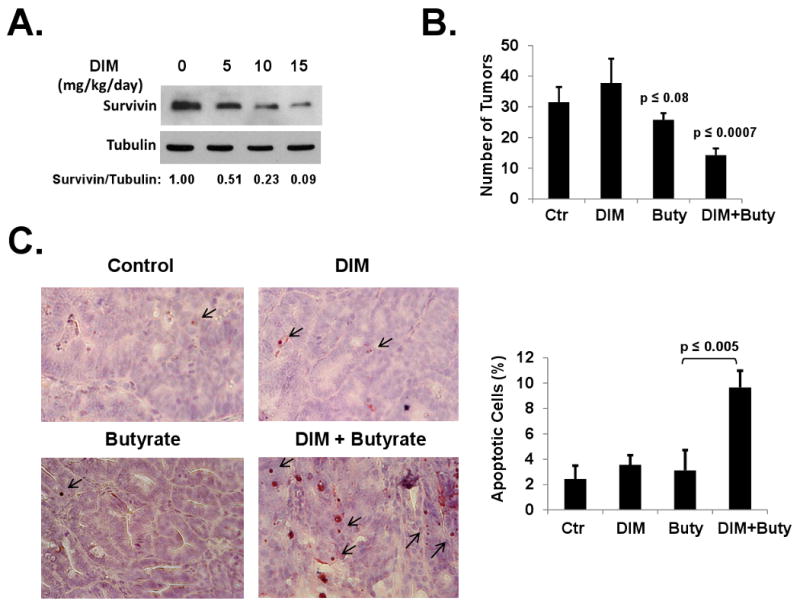

3,3′-Diindolylmethane enhances butyrate-induced apoptosis and efficacy of cancer prevention in APCmin/+ mice

We tested whether the DIM/butyrate combination strategy can be applied in vivo for cancer prevention in APCmin/+ mice. First, we tested whether DIM can down-regulate survivin in vivo in APCmin/+ mice and determined the optimal dose of DIM. As shown in Figure 6A, oral administration of various doses of DIM was effective in down-regulating survivin protein in the intestinal tumors from APCmin/+ mice. The optimal dose was determined to be 10 mg/kg/day due to the solubility of DIM. No toxicities (body weight loss, etc) were observed at these doses. APCmin/+ mice were then randomly assigned to four groups and treated with DIM or butyrate alone, or DIM/butyrate combination. As shown in Figure 6B, treatment with DIM/butyrate combination significantly decreased tumors numbers in APCmin/+ mice. While butyrate-treated group has slightly decreased number of tumors, DIM alone has no effects on the number of tumors in these mice. To examine apoptosis in tumors, separate groups of mice were treated with doses and schedule as above and sacrificed immediately after drug treatment since apoptotic cells are cleared quickly in vivo. We performed in vivo TUNEL assay to determine the level of apoptosis in the tumors isolated from APCmin/+ mice. As shown in Figure 6C, significant higher levels of apoptosis were observed in the mice receiving DIM/butyrate combination treatment, comparing to the low levels of apoptosis in control group or mice receiving single drug treatment.

Figure 6. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane enhances butyrate-induced apoptosis and efficacy of cancer prevention in APCmin/+ mice.

(A) DIM down-regulated survivin in tumors of APCmin/+ mice. Twelve weeks old APCmin/+ mice were separated into four groups with five mice in each group. DIM were administered at an oral dose of 0, 5, 10, and 15 mg/kg/day on days 1, 3, and 5. The tumor samples collected 24h after the last dose were analyzed by western blotting. Relative protein levels were quantified and shown under the gels. (B) APCmin/+ mice (six weeks old) were randomly assigned to four groups (5 mice each): control, DIM alone, butyrate alone, DIM/butyrate combination. For DIM and DIM/butyrate group, DIM was administered at 10 mg/kg/day on days 1, 3, and 5 during week six. Butyrate was administered for one week, at the dose of 24 mg daily, starting on day 1 of week six for the butyrate group and on day 7 of week six for the DIM/butyrate group. Mice in the control group were treated with regular water. At 16 weeks of age, Mice were euthanized and tumors were counted under a dissection microscope. The experiments were repeated once. (C) APCmin/+ mice (14 weeks old) were treated in four groups (five mice in each group) with the same doses and schedule as described in (B). The mice were sacrificed at 24 hours after administration of the last dose of agents and the tumor specimens were fixed in formalin. Paraffin sections of the tumors were examined for apoptosis using an ApopTag In situ Apoptosis Detection kit. Apoptosis indices (shown on right) were calculated as the percentage of apoptotic cells among 1000 tumor cells in randomly selected fields (> 5 fields per slide) from 5-6 slides for each treatment group. The experiments were repeated twice.

Discussion

This study has provided strong support for a novel combination strategy of using 3,3′-Diindolylmethane and butyrate for colon cancer prevention. Short-chain fatty acids, mainly acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are produced during bacteria fermentation of resistant starch and nonstarch polysaccharides (major components of dietary fiber) in the human colon 47. Butyrate is the major energy source for intestinal epithelial cells 48. By promoting cell differentiation, cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis of transformed colonocytes 49-51, butyrate has been regarded as a cancer preventive agent and extensively evaluated for colon cancer prevention 52,53. However, the effects of butyrate in prevention of animal models of colon cancer are often limited and in some cases butyrate even promotes tumor occurrence 11-13,54. Butyrate is an inhibitor of HDAC enzymes 3,55. We have recently demonstrated that APC mutations in colon cancer cells cause resistance to HDAC inhibitors in general due to a failure of survivin down-regulation 14. In the present study, we found that APC mutations also caused resistance to apoptosis in colon cancer cells treated with butyrate, as survivin was not down-regulated by butyrate in these cells. Thus, down-regulation of survivin is the key target to overcome colon cancer resistance to butyrate in cancer prevention.

DIM is a natural compound formed during the autolytic breakdown of glucobrassicin present in food plants of the Brassica genus, including broccoli, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower and kale 56. We found that DIM is very effective in down-regulating survivin and DIM is able to significantly potentiate butyrate-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells expressing mutant APC. Although survivin is not the only target for DIM, our data indicate that down-regulation of survivin plays a key role in DIM-mediated effects on apoptosis. While overexpression of survivin blocked DIM/butyrate-induced apoptosis in HT-29 cells, knocking-down survivin protein by siRNA successfully bypassed the requirement of DIM and induced apoptosis after butyrate treatment (Figure 4). Other efforts have been developed to inhibit survivin by antisense and ribozymes 57-59 and by using survivin mutants to suppress wild-type survivin 60. However, as a non-toxic small molecule agent, DIM may prove to be more effective and safer for cancer prevention purpose.

We have previously demonstrated that HDAC inhibitors down-regulate survivin through a GSK-3β/β-catenin/Tcf-4 pathway which is dependent on the expression of wild-type APC 14. Thus, HT-29 cells were resistant to butyrate-induced apoptosis due to the mutations of APC. Here, we show that by down-regulating cyclin B1, DIM is able to cause survivin degradation through an alternative mechanism independent of the status of APC. This mechanism involves a decrease of survivin Thr34 phosphorylation and resulting destabilization of survivin, successfully bypassing the requirement of wild-type APC. Through this mechanism, DIM is able to promote survivin degradation in HT-29 cells.

Down-regulation of survivin in HT-29 cells by transfection of survivin-targeting siRNA is not enough to cause apoptosis in our experiments. Apparently, other changes that occurred in the colon cancer cells (inhibition of HDACs, activation of Bax and Bak, and release of Smac and cytochrome c) in response to DIM/butyrate treatment contribute to the increased induction of apoptosis (Figure 3). The decrease of survivin lowers the threshold for apoptosis induction. We found that activation of caspase-3, caspase-7, and caspase-9 is involved in DIM/butyrate-induced apoptosis in HT-29 and IMCE cells, further indicating a role for the mitochondria-mediated intrinsic pathway of apoptosis 61.

In this report, we demonstrated that DIM is not only effective in in vitro studies, but more importantly DIM is effective in enhancing butyrate-induced apoptosis and improving the efficacy of cancer prevention in APCmin/+ mice. We employed a three-dose schedule for DIM (one dose every other day, and one week treatment of butyrate in drinking water). By fine-tuning the doses of DIM and butyrate as well as the scheduling of treatment, further improvement on the efficacy of cancer prevention can be potentially achieved. Taken together, the present findings have important implications for the clinical use of butyrate in colon cancer prevention. Using DIM in combination with butyrate may prove to be an effective strategy for the prevention of colorectal cancers in patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants 1R03CA130062 and 5R21CA111765 from the National Cancer Institute and by Grant Number 2P20RR015566 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. The authors are thankful for Jodie Haring of Center for Protease Research (North Dakota State University) who provided help for real-time PCR. Dr. Bert Vogelstein is gratefully acknowledged for providing HT-29/APC and HT-29/β-Gal cells. We thank Dr. Robert H. Whitehead of Vanderbilt University for providing the IMCE cells.

References

- 1.Corpet DE, Pierre F. Point: From animal models to prevention of colon cancer. Systematic review of chemoprevention in min mice and choice of the model system. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:391–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corpet DE, Pierre F. How good are rodent models of carcinogenesis in predicting efficacy in humans? A systematic review and meta-analysis of colon chemoprevention in rats, mice and men. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1911–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dashwood RH, Myzak MC, Ho E. Dietary HDAC inhibitors: time to rethink weak ligands in cancer chemoprevention? Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:344–349. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuefer R, Hofer MD, Altug V, et al. Sodium butyrate and tributyrin induce in vivo growth inhibition and apoptosis in human prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:535–541. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks P, Rifkind RA, Richon VM, Breslow R, Miller T, Kelly WK. Histone deacetylases and cancer: causes and therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:194–202. doi: 10.1038/35106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnstone RW, Licht JD. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy: is transcription the primary target? Cancer Cell. 2003;4:13–18. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks PA, Richon VM, Rifkind RA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: inducers of differentiation or apoptosis of transformed cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1210–1216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.15.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassig CA, Tong JK, Schreiber SL. Fiber-derived butyrate and the prevention of colon cancer. Chem Biol. 1997;4:783–789. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YS, Milner JA. Dietary modulation of colon cancer risk. J Nutr. 2007;137:2576S–2579S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2576S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman HJ. Effects of differing concentrations of sodium butyrate on 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced rat intestinal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:596–602. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90628-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caderni G, Luceri C, Lancioni L, Tessitore L, Dolara P. Slow-release pellets of sodium butyrate increase apoptosis in the colon of rats treated with azoxymethane, without affecting aberrant crypt foci and colonic proliferation. Nutr Cancer. 1998;30:175–181. doi: 10.1080/01635589809514660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caderni G, Luceri C, De Filippo C, et al. Slow-release pellets of sodium butyrate do not modify azoxymethane (AOM)-induced intestinal carcinogenesis in F344 rats. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:525–527. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang X, Guo B. Adenomatous polyposis coli determines sensitivity to histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9245–9251. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy DB, Smith KJ, Beazer-Barclay Y, Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Inactivation of both APC alleles in human and mouse tumors. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5953–5958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikuchi-Yanoshita R, Konishi M, Fukunari H, Tanaka K, Miyaki M. Loss of expression of the DCC gene during progression of colorectal carcinomas in familial adenomatous polyposis and non-familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3801–3803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidransky D, Tokino T, Hamilton SR, et al. Identification of ras oncogene mutations in the stool of patients with curable colorectal tumors. Science. 1992;256:102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1566048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirasawa S, Urabe K, Yanagawa Y, Toshitani K, Iwama T, Sasazuki T. p53 gene mutations in colorectal tumors from patients with familial polyposis coli. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2874–2878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giles RH, van Es JH, Clevers H. Caught up in a Wnt storm: Wnt signaling in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1653:1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kuhl M, et al. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382:638–642. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin PJ. beta-catenin signaling and cancer. Bioessays. 1999;21:1021–1030. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199912)22:1<1021::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moser AR, Pitot HC, Dove WF. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247:322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu P, Martin E, Mengwasser J, Schlag P, Janssen KP, Gottlicher M. Induction of HDAC2 expression upon loss of APC in colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:455–463. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altieri DC. Validating survivin as a cancer therapeutic target. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:46–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheatley SP, Carvalho A, Vagnarelli P, Earnshaw WC. INCENP is required for proper targeting of Survivin to the centromeres and the anaphase spindle during mitosis. Curr Biol. 2001;11:886–890. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong Y, Sohn H, Xue L, Firestone GL, Bjeldanes LF. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane is a novel mitochondrial H(+)-ATP synthase inhibitor that can induce p21(Cip1/Waf1) expression by induction of oxidative stress in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4880–4887. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhuiyan MM, Li Y, Banerjee S, et al. Down-regulation of androgen receptor by 3,3′-diindolylmethane contributes to inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in both hormone-sensitive LNCaP and insensitive C4-2B prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10064–10072. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong D, Banerjee S, Huang W, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin repression by 3,3′-diindolylmethane inhibits invasion and angiogenesis in platelet-derived growth factor-D-overexpressing PC3 cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1927–1934. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Xu J, Jhala N, et al. Fas-mediated apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cells is enhanced by 3,3′-diindolylmethane through inhibition of AKT signaling and FLICE-like inhibitory protein. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1833–1842. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim EJ, Park SY, Shin HK, Kwon DY, Surh YJ, Park JH. Activation of caspase-8 contributes to 3,3′-Diindolylmethane-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. J Nutr. 2007;137:31–36. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahman KM, Ali S, Aboukameel A, et al. Inactivation of NF-kappaB by 3,3′-diindolylmethane contributes to increased apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agent in breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2757–2765. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman KW, Li Y, Wang Z, Sarkar SH, Sarkar FH. Gene expression profiling revealed survivin as a target of 3,3′-diindolylmethane-induced cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4952–4960. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kong D, Li Y, Wang Z, Banerjee S, Sarkar FH. Inhibition of angiogenesis and invasion by 3,3′-diindolylmethane is mediated by the nuclear factor-kappaB downstream target genes MMP-9 and uPA that regulated bioavailability of vascular endothelial growth factor in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3310–3319. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Apoptosis and APC in colorectal tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7950–7954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolfensohn S, Lloyd M. Handbook of Laboratory Animal Management and Welfare. Blackwell; Oxford: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Connor DS, Grossman D, Plescia J, et al. Regulation of apoptosis at cell division by p34cdc2 phosphorylation of survivin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13103–13107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240390697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wall NR, O'Connor DS, Plescia J, Pommier Y, Altieri DC. Suppression of survivin phosphorylation on Thr34 by flavopiridol enhances tumor cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindsten T, Ross AJ, King A, et al. The combined functions of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members bak and bax are essential for normal development of multiple tissues. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00136-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chittenden T. BH3 domains: intracellular death-ligands critical for initiating apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:165–166. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gross A, Jockel J, Wei MC, Korsmeyer SJ. Enforced dimerization of BAX results in its translocation, mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. Embo J. 1998;17:3878–3885. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo B, Yin MB, Toth K, Cao S, Azrak RG, Rustum YM. Dimerization of mitochondrial Bax is associated with increased drug response in Bax-transfected A253 cells. Oncol Res. 1999;11:91–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell. 1996;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2922–2933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du C, Fang M, Li Y, Li L, Wang X. Smac, a mitochondrial protein that promotes cytochrome c-dependent caspase activation by eliminating IAP inhibition. Cell. 2000;102:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitehead RH, Joseph JL. Derivation of conditionally immortalized cell lines containing the Min mutation from the normal colonic mucosa and other tissues of an “Immortomouse”/Min hybrid. Epithelial Cell Biol. 1994;3:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Topping DL, Clifton PM. Short-chain fatty acids and human colonic function: roles of resistant starch and nonstarch polysaccharides. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1031–1064. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roediger WE. Utilization of nutrients by isolated epithelial cells of the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:424–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hague A, Manning AM, Hanlon KA, Huschtscha LI, Hart D, Paraskeva C. Sodium butyrate induces apoptosis in human colonic tumour cell lines in a p53-independent pathway: implications for the possible role of dietary fibre in the prevention of large-bowel cancer. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:498–505. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heerdt BG, Houston MA, Augenlicht LH. Potentiation by specific short-chain fatty acids of differentiation and apoptosis in human colonic carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3288–3293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heerdt BG, Houston MA, Augenlicht LH. Short-chain fatty acid-initiated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells is linked to mitochondrial function. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:523–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong JM, de Souza R, Kendall CW, Emam A, Jenkins DJ. Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:235–243. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200603000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lupton JR. Microbial degradation products influence colon cancer risk: the butyrate controversy. J Nutr. 2004;134:479–482. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.2.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zoran DL, Turner ND, Taddeo SS, Chapkin RS, Lupton JR. Wheat bran diet reduces tumor incidence in a rat model of colon cancer independent of effects on distal luminal butyrate concentrations. J Nutr. 1997;127:2217–2225. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.11.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jung M. Inhibitors of histone deacetylase as new anticancer agents. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:1505–1511. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aggarwal BB, Ichikawa H. Molecular targets and anticancer potential of indole-3-carbinol and its derivatives. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1201–1215. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Sirugo G, Altieri DC. Induction of apoptosis and inhibition of cell proliferation by survivin gene targeting. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11177–11182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kanwar JR, Shen WP, Kanwar RK, Berg RW, Krissansen GW. Effects of survivin antagonists on growth of established tumors and B7-1 immunogene therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1541–1552. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.20.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pennati M, Binda M, De Cesare M, et al. Ribozyme-mediated down-regulation of survivin expression sensitizes human melanoma cells to topotecan in vitro and in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1129–1136. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mesri M, Wall NR, Li J, Kim RW, Altieri DC. Cancer gene therapy using a survivin mutant adenovirus. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:981–990. doi: 10.1172/JCI12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]