Abstract

A facile iterative synthesis of 2,5-terpyrimidinylenes that are structurally analogous to α-helix mimics is presented. Condensation of amidines with readily prepared α,β-unsaturated α-cyanoketones gives 5-cyano substituted pyrimidines. Iterative transformation of the 5-cyano group into an amidine allows synthesis of 2,5-terpyrimidinylenes with variable groups at the 4-, 4′-, and 4″- positions. These compounds are designed to mimic the i, i+4, and i+7 sites of an α-helix.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are involved in several cellular processes and the specific modulation of these interactions will boost our understanding of these processes.1,2 Furthermore, PPI inhibitors can be the basis of important therapeutic interventions.3-8 PPIs are typically shallow surface interactions that occur over relatively large surface areas to accrue sufficient interactions between the protein surfaces and stabilize their specific interaction with each other.9-12 Thus, the development of specific PPI inhibitors is a challenging task as compared to enzyme inhibitors which typically have relatively small and deep binding pockets.

Several different secondary and tertiary structures can be involved in the PPI and one that is the focus of this manuscript is the α-helix. Hamilton et al. have discovered α-helix mimics that act as sub-micromolar inhibitors of the Bcl-xL interaction with the Bak peptide and the MDM2 interaction with the p53 peptide derived from the p53 N-terminus.13, 14 The Hamilton group has reported several α-helix mimics, but none of them have been more active than the best reported 1,4-terphenylene scaffolds against the same targets in the same in vitro assays.15-19

Rebek et al. recognized the importance of Hamilton's α-helix mimic approach and published several examples of more polar versions of the original Hamilton 1,4-terphenylene scaffold 20-24 including a tetrameric heterocyclic α-helix mimic scaffold designed to position four side chains in the i, i+4, i+7, and i+11 positions of an α-helix.24 Recently, Hamilton's group has also published a repetitive heterocyclic scaffold approach.25 The intense efforts of these research groups to develop repetitive heterocyclic scaffolds to mimic α-helices illustrates the very strong potential importance of this class of compounds.

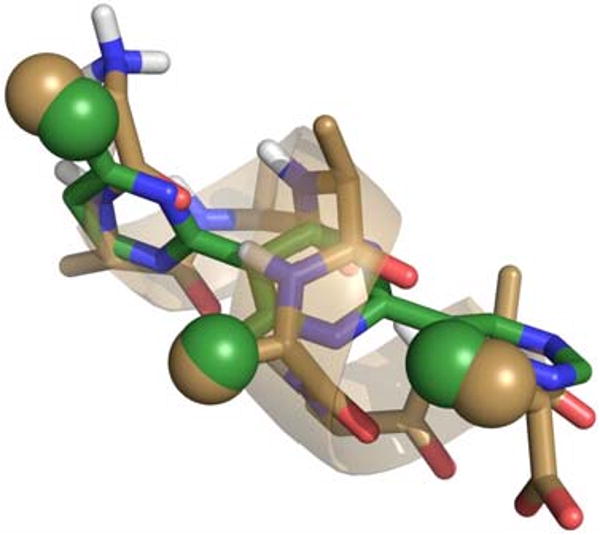

With the seminal work from the Hamilton group on the 1,4-terphenylene scaffold as a guide, we have developed a facile iterative synthesis of 2,5-terpyrimidinylenes as structurally analogous α-helix mimics.26,27 Figure 1 shows an overlay of octa-alanine in an idealized α-helical conformation with its i, i+4, and i+7 methyl groups highlighted as gold spheres and a 4,4′,4″-trimethyl-2,5-terpyrimidinylene with its methyl groups highlighted as green spheres.

Figure 1.

A tube representation of an idealized α-helix of octaalanine (gold with transparent ribbon) with the i, i+4, and i+7 methyl groups highlighted as spheres and an overlay with a 4,4′,4″-trimethyl-2,5-terpyrimidinylene with its methyl groups highlighted as green spheres is shown above. The RMSD for the highlighted methyl groups is 0.68 Å. For clarity, only polar hydrogens are shown. The details of these calculations can be found in the supporting information.

As seen with the Hamilton designed 1,4-terphenylene scaffold,16 there is a good overlap of these positions, both in orientation and distance. Residues at the i+4 position are one turn plus 40° and i+7 residues are 20° less than two turns of an α-helix from the i position. Our 2,5-terpyrimidinylene scaffold essentially replaces the phenyl rings of Hamilton's 1,4-terphenylene scaffold with pyrimidine rings, but these changes make the synthesis of pyrimidine-based derivatives much easier because the pyrimidine synthetic chemistry is more convergent and amenable to an iterative synthetic approach.

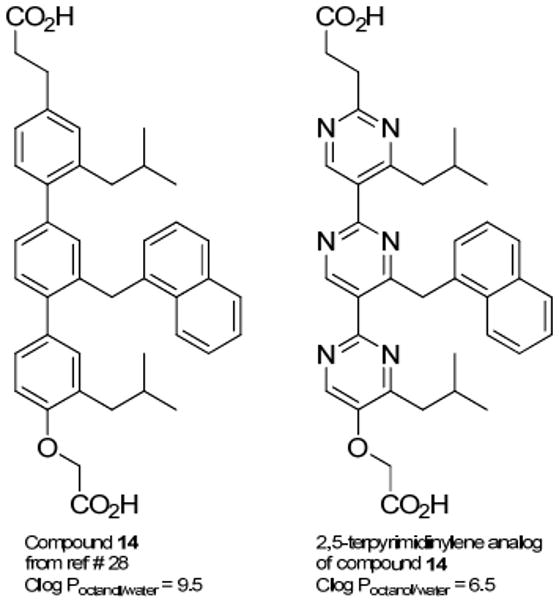

In addition, the pyrimidine for phenyl replacement gives the resulting analogous pyrimidine scaffold improved hydrophilicity according to QikProp calculations summarized in Figure 2 and Table 1, Supporting Information A. Structurally analogous 1,4-terphenylene and 2,5-terpyrimidinylene scaffolds show the calculated log Poctanol/water values ranging from hydrophobic behavior for the Hamilton 1,4-terphenylene scaffold28 to within the desirable range for hydrophilic character for the analogous 2,5-terpyrimidinylene scaffold (see Supporting Information A-Table 1)

Figure 2.

QikProp calculations for the most active terphenyl-based Bcl-xL-Bak inhibitor and the analogous terpyrimidine-based analog shows improved hydrophilic character.

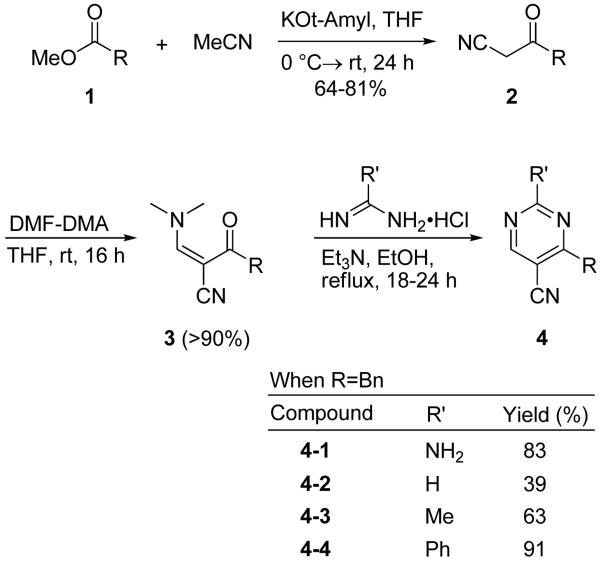

Pyrimidine monomers 4 were obtained in a few steps through the condensation of commercially available amidines with readily prepared α,β-unsaturated α-cyanoketones 3 (Scheme 1). For instance, ester 1 was reacted with acetonitrile in anhydrous THF in the presence of KO-t-amyl to obtain α-cyanoketone 2.29,30 These reactions were also carried out in presence of other bases, including NaOMe,31 KOt-Bu, and LDA (data not shown). While the desired α-cyanoketone was obtained from the reactions with these bases, the isolation and purification was tedious resulting in lower yields. KO-t-amyl afforded the products in good yields with simpler purification conditions.

Scheme 1.

Representative synthesis of pyrimidines 4.

Treatment of compound 2 with N,N-dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal (DMF-DMA) in THF gave 3 in excellent yield.32 The efficiency of this step allowed us to obtain several α,β-unsaturated α-cyanoketones bearing hydrophobic alkyl, aryl, and heteroaromatic groups for introducing diversity in the 4-position of pyrimidines. As shown in Scheme 1, monomers 4-1 and 4-4 were isolated in higher yields and no further purification was required since these compounds precipitated from the reaction mixtures, whereas 4-2 and 4-3 required additional purification. Encouraged by the excellent yields and purities obtained when R′=Ph, we next focused on the iterative synthesis of the dimeric and trimeric 2,5-pyrimidines.

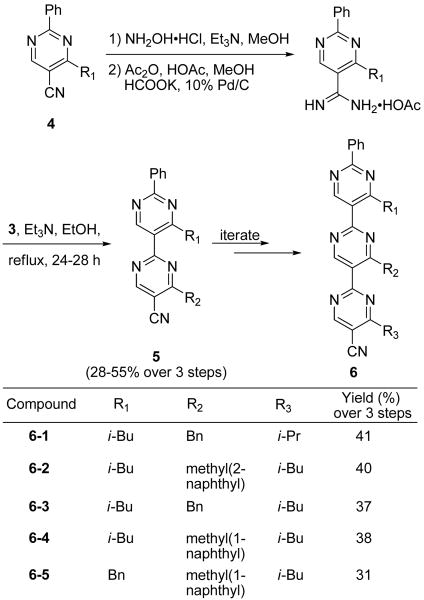

Compounds 5 and 6 were synthesized via conversion of the 5- or 5′-cyano group to a 5- or 5′-carboxamidine salt (Scheme 2). Several methods for this conversion have been reported,33, 34 such as the Pinner,35 the thio-Pinner,36 or treatment with Na or LiHMDS followed by aqueous hydrolysis,37 but none of these alternatives were superior to the two-step hydroxylamine route.38,39

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of dimeric and trimeric 2,5-pyrimidines

The extensive literature on nitrile to amidine conversion suggests that the difficulty of such a conversion can be attributed to the ortho substitution on the pyrimidine ring.40 We found excess hydroxylamine followed by an in situ reduction of the resulting amidoxime was the best route to obtain the intermediate amidine salts. The N-hydroxylamine mediated transformation of ortho-substituted arylnitrile groups to arylcarboxamidines has been reported, 41 but has not been used previously to prepare oligo-2,5-pyrimidines. The resulting intermediate amidine salts were reacted with an α,β-unsaturated α-cyanoketone to yield dimers 5.

Dimers as well as trimers were isolated. The R1, R2, and R3 groups of the 2,5-terpyrimidinylene scaffold were selected to mimic hydrophobic groups found to play important roles in binding similar to the Hamilton terphenylene compounds.28

The ORTEP diagram of the 4′-benzyl-4-(1-methylethyl)-4″-(2-methylpropyl)-2″-phenyl-2,5′,2′,5″-terpyrimidinylene-5-carbonitrile (6-1) crystal structure is shown in Figure 3. This conformation places the three hydrophobic groups on the same side of the long axis of the molecule which is the conformer needed to mimic the i, i+4, and i+7 residues of an α-helix.

Figure 3.

ORTEP diagram of compound 6-1

In conclusion, a series of compounds based on novel 2,5-terpyrimidinylenes was obtained through a facile iterative condensation between amidines and α,β-unsaturated α-cyanoketones in the presence of a base. This scaffold is being explored as α-helical mimics for the disruption of various protein-protein interactions; our efforts in this direction will be reported subsequently.

Experimental Section (see Supporting Information for the complete series)

5-Methyl-3-oxohexanenitrile (2a)

A mixture of potassium t-pentylate (∼1.7 M in toluene, 136 mmol, 80 mL) and anhydrous THF (20 mL) was cooled at 0 °C in an ice-bath under an argon atmosphere. Anhyd. acetonitrile (136 mmol, 7.14 mL) and methyl ester 1a (90 mmol, 10.57 g, 12 mL) were added simultaneously to the cold solution. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred under an argon atmosphere for 22 h. A precipitate was formed within a few minutes (3-5 min.) of stirring and the reaction mixture remained cloudy until completion. The reaction was monitored by TLC and was stopped when the TLC indicated the consumption of the ester (1a). The mixture was filtered and the filtered cake was washed thoroughly with hexanes (80 mL). The filtered residue was then transferred to a separatory funnel and acidified to pH= ∼2-3 with saturated aq. KHSO4 solution (180 mL). An equal volume amount of DCM (180 mL) was used to extract the desired compound (2a). The organic layer was collected and washed with brine (100 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield 2a in 73% yield, as a pale yellow oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.95 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 3H), 3.43 (s, 2H), 2.11-2.25 (m, 1H), 2.49 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.5, 24.7, 32.6, 51.1, 113.9, 197.2.

(E)-2-((Dimethylamino)methylene)-5-methyl-3-oxohexanenitrile(3a)

α-cyanoketone 2a (65.9 mmol, 825 mg) was dissolved in dry THF (3 mL) under an argon atmosphere. N,N-dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal (85.6 mmol, 11.5 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred at room temperature. Progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC until complete consumption of starting material 2a was observed (16 h). The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the desired compound was obtained as an E≫Z isomeric mixture. Isolated yield: 98 %, pale yellow solid, m.p. 43-45 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.95 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 3H), 0.96 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 3H), 2.13-2.25 (m, 1H), 2.54 (dd, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.24 (s, 3H), 3.40 (s, 3H), 7.82 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.8, 25.8, 39.0, 48.1, 48.8, 80.8, 120.6, 157.6, 195.4. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C10H16N2O [M + H]+ 181.1341, found 181.1333. Note: If a precipitate forms during the reaction, the mixture is cooled to 0 °C and then filtered and rinsed with cold THF to isolate the desired compound.

4-Isobutyl-2-phenylpyrimidine-5-carbonitrile(4-5)

Method A: A mixture of compound 3a (1.66 mmol, 300 mg) and benzamidine hydrochloride (3.33 mmol, 521 mg) in ethanol (absolute, 10 mL) was stirred under reflux until the TLC indicated completion of the reaction. The mixture was brought to room temperature and the precipitate formed was filtered and rinsed with ice cold ethanol (3 × 5 mL). Compound 4-5 was isolated in 70% yield as colorless crystals, m.p. 68-69 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.05 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H), 2.39 (m, 1H), 2.93 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.49 – 7.59 (m, 3H), 8.50 – 8.53 (m, 2H), 8.93 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.6, 28.9, 45.7, 106.7, 115.8, 129.0, 129.4, 132. 4, 136.4, 160.4, 165.7, 173.3. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C15H15N3 [M + H]+ 238.1344, found 238.1337. Method B: Microwave-assisted reactions were also done in the presence of base (e.g. Et3N or NaOEt) to obtain the desired pyrimidines. For example, to a mixture of compound 3a (1.11 mmol, 200 mg) and benzamidine hydrochloride (2.22 mmol, 350 mg) in ethanol (5 mL) was added sodium ethoxide (1.11 mmol, 75.5 mg) suspended in ethanol (1 mL). The reaction mixture was placed in a microwave reactor for 40 min. at 120 °C. A colorless precipitate was formed upon cooling to room temperature. The precipitate was filtered and rinsed with ice cold ethanol (2 × 3 mL) to isolate compound 4-5 in 83% yield.

4-Benzyl-4′-isobutyl-2′-phenyl-2,5′-bipyrimidine-5-carbo nitrile (5-1)

Step 1

To a mixture of compound 4-5 (4.21 mmol, 1000 mg) and hydroxylamine hydrochloride (10.53 mmol, 720 mg) in methanol (12 mL) was added triethylamine (10.53 mmol, 1.46 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred under reflux until the TLC indicated the consumption of starting material 4-5. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to obtain a white crude solid. The crude was dissolved in DCM (50 mL), washed with water (40 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain intermediate amidoxime, which was used in the next step without further purification.

Step 2

Intermediate from step 1 (0.92 mmol, 250 mg) was dissolved in glacial acetic acid (1 mL) and acetic anhydride (1.01 mmol, 0.1 mL). After stirring for 5 min., potassium formate prepared in situ from K2CO3 (5 mmol, 690 mg), formic acid (10 mmol, 0.37 mL) in methanol (2.5 mL) was added to the mixture followed by the addition of 10% Pd/C (10 mol %, 98 mg). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature until the TLC indicated the consumption of starting material. The crude was filtered through Celite™ (1500 mg) and rinsed with methanol (3 × 3 mL). The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain a yellow crude residue. To this residue, DCM (6 mL) was added and the white precipitate that formed was removed by vacuum filtration. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain the crude acetate salt of carboxamidine as a yellow solid, which was used without further purification in the next step.

Step 3

To the crude carboxamidine salt dissolved in ethanol (0.8 mL) was added compound 3a (0.69 mmol, 147 mg) and triethylamine (1.38 mmol, 0.19 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred under reflux for 2 h and then at room temperature for 18 h. A white precipitate was formed, which was filtered and rinsed with cold ethanol (5 mL) to yield dimer 5-1 in 28% yield after three steps, white solid, m.p. 144-147 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.92 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H), 2.24 – 2.35 (m, 1H), 3.19 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.39 (s, 2H), 7.27 – 7.39 (m, 5H), 7.43 – 7.56 (m, 5H), 9.02 (s, 1H), 9.38 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.8, 28.4, 43.4, 44.9, 106.3, 115.2, 127.6, 127.8, 128.8, 129.0, 129.2, 129.5, 131.5, 135.8, 137.4, 160.0, 160.7, 164.7, 165.8, 170.3, 172.0. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C26H23N5 [M + H]+ 406.2032, found 406.2049.

5″-Cyano-4,4″-diisobutyl-4′-(2-phenylmethyl)-2-phenylterpyrimidine (6-1)

Repeat steps 1-3 as in synthesis of dimer 5-1 starting with 5-1. Isolated yield = 37% after three steps, white solid, m.p. 188-189 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.90 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H), 1.02 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H), 2.22 – 2.36 (m, 2H), 2.95 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.20 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.77 (s, 2H), 7.17 – 7.25 (m, 5H), 7.49 – 7.54 (m, 3H), 8.52 – 8.58 (m, 2H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 9.38 (s, 1H), 9.52 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 22.6, 22.8, 28.5, 29.2, 42.3, 44.7, 45.8, 107.6, 115.0, 126.8, 127.4, 128.56, 128.7, 128.8, 128.8, 129.3, 131.1, 137.8, 138.3, 159.6, 160.1, 160.3, 164.2, 164.6, 164.8, 169.0, 170.0, 173.8. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C34H33N7 [M + H]+ 540.2876, found 540.2869.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH for financial support through grant NCI P01 CA118210. We also thank the HTS-Chemistry Core Facility at Moffitt Cancer Center for use of the Biotage initiator microwave synthesizer.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, spectroscopic data for new compounds, and crystal structure of compound 6-1. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Berg T. Curr Opin Drug Discovery Dev. 2008;11:666–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saraogi I, Hamilton AD. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:1414–1417. doi: 10.1042/BST0361414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ockey DA, Gadek TR. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2002;12:393–400. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arkin MR, Wells JA. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2004;3:301–317. doi: 10.1038/nrd1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pagliaro L, Felding J, Audouze K, Nielsen SJ, Terry RB, Krog-Jensen C, Butcher S. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher S, Hamilton AD. Curr Top Med Chem (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2007;7:922–927. doi: 10.2174/156802607780906735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells JA, McClendon CL. Nature (London) 2007;450:1001–1009. doi: 10.1038/nature06526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin H, Hamilton AD. Chem Biol. 2007;1:250–269. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parthasarathi L, Casey F, Stein A, Aloy P, Shields DC. J Chem Inf Model. 2008;48:1943–1948. doi: 10.1021/ci800174c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neugebauer A, Hartmann RW, Klein CD. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4665–4668. doi: 10.1021/jm070533j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nieddu E, Pasa S. Curr Top Med Chem (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2007;7:21–32. doi: 10.2174/156802607779318271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher S, Hamilton AD. J R Soc Interface. 2006;3:215–233. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin H, Gui-in L, Park HS, Payne GA, Rodriguez JM, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:2704–2707. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Yin H, Farooqi B, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD, Chen J. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1019–1025. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst JT, Becerril J, Park HS, Yin H, Hamilton AD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:535–539. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin H, Gui-in L, Sedey KA, Rodriguez JM, Wang HG, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5463–5468. doi: 10.1021/ja0446404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JM, Truong A, Hamilton AD. Org Lett. 2005;7:5405–5408. doi: 10.1021/ol0521228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez JM, Hamilton AD. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:7443–7446. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saraogi I, Incarvito CD, Hamilton AD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:9691–9694. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moisan L, Odermatt S, Gombosuren N, Carella A, Rebek J. Eur J Org Chem. 2008;10:1673–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moisan L, Dale TJ, Gombosuren N, Biros SM, Mann E, Hou JL, Crisostomo FP, Rebek J. Heterocycles. 2007;73:661–671. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volonterio A, Moisan L, Rebek J. Org Lett. 2007;9:3733–3736. doi: 10.1021/ol701487g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biros SM, Moisan L, Mann E, Carella A, Zhai D, Reed JC, Rebek J. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:4641–4645. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.05.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Restorp P, Rebek J. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5909–5911. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cummings CG, Ross NT, Katt WP, Hamilton AD. Org Lett. 2009;11:25–28. doi: 10.1021/ol8022962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ernst JT, Kutzki O, Debnath AK, Jiang S, Lu H, Hamilton AD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:278–281. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020118)41:2<278::aid-anie278>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kutzki O, Park HS, Ernst JT, Orner BP, Yin H, Hamilton AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11838–11839. doi: 10.1021/ja026861k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin H, Lee Gi, Sedey KA, Kutzki O, Park HS, Orner BP, Ernst JT, Wang HG, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10191–10196. doi: 10.1021/ja050122x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaohui J, Trenkle WC, Vowles JV. Org Lett. 2006;8:1161–1163. doi: 10.1021/ol053164z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radwan MAA, Ragab EA, Shaaban MR, El-Nezhawy AOH. ARKIVOC. 2009;7:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorger K, Stohrer J. 20070142661 U.S Pat.

- 32.Reuman M, Beish S, Davis J, Batchelor MJ, Hutchings MC, Moffat DFC. J Org Chem. 2008;73:1121–1123. doi: 10.1021/jo7021372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill MD, Movassaghi M. Chem-Eur J. 2008;14:6836–6844. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunn PJ. Compr Org Funct Group Transform. 2005;II:655–699. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balo C, Lopez C, Brea JM, Fernandez F, Caamano O. Chem Pharm Bull. 2007;55:372–375. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lange UEW, Schafer B, Baucke D, Buschmann E, Mack H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:7067–7070. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruning J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:3187–3188. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Judkins BD, Allen DG, Cook TA, Evans B, Sardharwala TE. Synth Commun. 1996;26:4351–4367. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nadrah K, Dolenc MS. Synlett. 2007;8:1257–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Angerer S. Science of Synthesis. 2004;16:379–572. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basso A, Pegg N, Evans B, Bradley M. Eur J Org Chem. 2000;23:3887–3891. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.