Abstract

The effectiveness of genetic engineering with lentivectors to protect transplanted cells from allogeneic rejection was examined using, as a model, type 1 diabetes treatment with β cell transplantation, whose widespread use has been limited by the requirement for sustained immunosuppressive treatment to prevent graft rejection. We examined whether lentivectors expressing select immunosuppressive proteins encoded by the adenoviral genome early region 3 (AdE3) would protect transplanted β cells from an alloimmune attack. The insulin-producing β cell line βTC-tet (C3HeB/FeJ-derived) was transduced with lentiviruses encoding the AdE3 proteins gp19K and RIDα/β. The efficiency of lentiviral transduction of βTC-tet cells exceeded 85%. Lentivector expression of gp19K decreased surface class I MHC expression by over 90%, while RIDα/β expression inhibited cytokine-induced Fas upregulation by over 75%. βTC-tet cells transduced with gp19K and RIDα/β lentivectors, but not with a control lentivector, provided prolonged correction of hyperglycemia after transplantation into diabetic BALB/c SCID mice reconstituted with allogeneic immune effector cells or into diabetic allogeneic BALB/c mice. Thus, genetic engineering of β cells using gp19K and RIDα/β expressing lentiviral vectors may provide an alternative that has the potential to eliminate or reduce treatment with the potent immunosuppressive agents currently necessary for prolonged engraftment with transplanted islets.

Keywords: Lentiviral vectors, genetic engineering, diabetes, transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Genetic engineering using lentiviral vectors is a powerful technique that permits modification of cells to express defined genes, either to correct a genetic deficiency or to alter cellular function and in vivo biological behavior. Transplantation of a variety of cell types is currently being explored as a modality to treat several diseases caused by the absence or destruction of functionally critical cell populations1. For example, type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease characterized by the loss of the insulin-producing β cells present in the pancreatic islets, resulting in sustained hyperglycemia and subsequent damage to multiple organs. Although lifelong daily injections of insulin provide an effective palliative therapy for the disease, they do not constitute a cure. The need for chronic insulin therapy could be obviated by pancreatic islet transplantation, but less than 10% of patients remain insulin-independent five years after this procedure 2, due to alloimmune and autoimmune responses that develop despite treatment with potent immunosuppressive drugs3 and to the deleterious effects of the immunosuppressive agents on β cell maintenance and function4. Furthermore, the chronic immunosuppressive therapy required to allow sustained engraftment after transplantation of any allogeneic cell population increases the susceptibility of patients to infections and malignancies, and each drug has specific adverse side effects (e.g., nephrotoxicity) that may necessitate discontinuation2,5.

An alternative to chronic immunosuppressive therapy for transplant recipients would be to transplant cells that have been genetically modified to protect them from detection and/or elimination by the immune system of the recipient. To explore the efficacy of this approach, we hypothesized that we could examine the capacity of genetic engineering to protect transplanted cells from rejection by genetically engineering β cells to express selected immunosuppressive adenoviral (Ad) proteins, encoded in early region 3 (E3) of the viral genome. The E3 region encodes seven proteins, several of which inhibit the capacity of the immune system to recognize and eliminate infected cells and thereby protect Ad-infected cells from clearance by the host6. For example, the AdE3-encoded RID (Receptor Internalization and Degradation) complex, composed of α and β subunits, inhibits apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and other members of the TNF family such as Fas and TRAIL7–9, blocks TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation of proinflammatory genes10, and suppresses the synthesis of chemokines11. Another AdE3-encoded protein, gp19K, inhibits the surface expression of class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, thereby preventing the infected cells from presenting Ad-derived peptides on their surface, thus forestalling their resultant elimination by Ad-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL)12. Some of the immune pathways inhibited by the AdE3 proteins to prevent elimination of Ad-infected cells have also been implicated in the rejection of allogeneic transplanted islets13,14 as well as the autoimmune-mediated etiology of type 1 diabetes15,16,

Islet cells from mice transgenic for the expression of the entire AdE3 region under the control of the rat insulin II promoter (RIP) were protected from allograft rejection17 and β cell-specific autoimmunity18–20. These studies using transgenic mice suggested that the expression of all of the AdE3 genes by β cells could facilitate their transplantation across allogeneic barriers, without a requirement for continued systemic immunosuppression, and could also inhibit autoimmune destruction of β cells. However, transgenic modification of human islets prior to transplantation to express all seven proteins encoded by the AdE3 region for clinical use is not feasible. Furthermore, given the shortage of human islets and the focus on generating reproducible, transplantable cell lines for transplantation in type 1 diabetes as opposed to whole islets, we utilized the clinically feasible approach of using lentiviral vectors to determine whether expression of just three proteins, RIDα, RIDβ and gp19K, would be sufficient to protect islet cells from allogeneic rejection. Human T cells modified ex vivo by lentiviral vectors were recently shown to be safe in a Phase I clinical trial for HIV-1 gene therapy21. No adverse events or instances of insertional mutagenesis were reported after up to three years of follow-up, suggesting the potential clinical feasibility of lentiviral-mediated gene transfer for treatment of other diseases, including type 1 diabetes. In the current report, we demonstrate that lentiviral vectors can be used to engineer the insulin-secreting murine β cell line βTC-tet22,23 to express three AdE3 proteins, RIDα, RIDβ and gp19K. We overcame the requirement for coordinated expression of the RID α and β subunits for functional activity of the RID complex by expressing both together using a single lentiviral vector engineered to express RIDα and RIDβ linked with a “self-cleaving” picornavirus 2A peptide that enables the stoichiometric production of two proteins from a single transcript24. We report that βTC-tet cells genetically engineered to express RIDα/β and gp19K by lentiviral transduction provided prolonged correction of hyperglycemia after transplantation into diabetic SCID mice reconstituted with allogeneic immune effector cells or into diabetic allogeneic BALB/c mice.

RESULTS

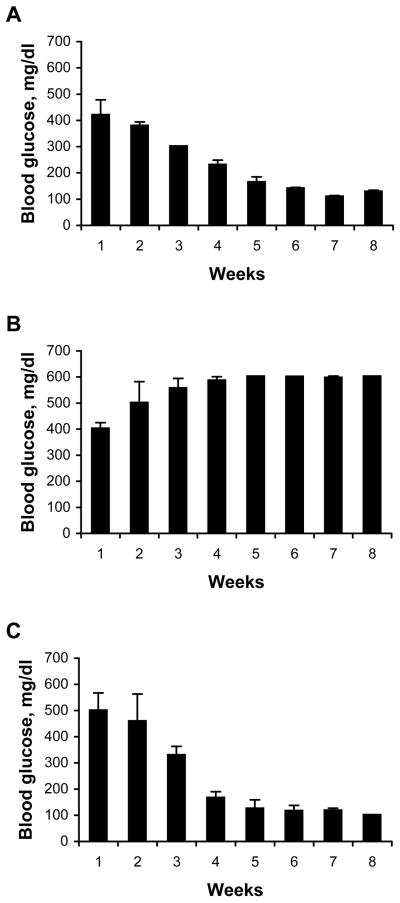

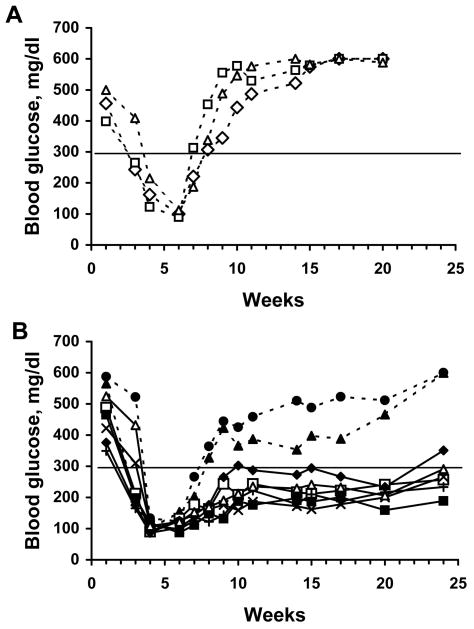

Development of a mouse model to study allogeneic rejection of islet cells

To study the capacity of lentiviral vectors to genetically engineer cells to resist allogeneic rejection, we used a model of transplantation-mediated treatment of type 1 diabetes utilizing a conditionally immortalized, insulin-producing β cell line βTC-tet derived from a mouse insulinoma22,23. Insulin production by βTC-tet cells is regulated in a glucose-dependent manner permitting these cells to maintain physiologically normal serum glucose levels in vivo23. Proliferation of the βTC-tet cells is induced by expression of a stably integrated simian virus 40 (SV40) large tumor antigen (TAg) that is negatively regulated by tetracycline22,23. This permits reversible arrest of the in vivo growth of the βTC-tet cells after transplantation into mice by adding doxycycline to the drinking water of the recipient mouse. As previously reported22, transplantation of the βTC-tet cells into syngeneic C3HeB/FeJ mice made diabetic by STZ treatment, corrected hyperglycemia and mediated prolonged normoglycemia (Fig. 1A). In contrast, βTC-tet cells transplanted into diabetic allogeneic BALB/c mice had no significant effect on hyperglycemia, likely a result of immune rejection of the transplanted cells (Fig. 1B). To study the capacity of genetic engineering using lentiviral vectors expressing immmunoinhibitory genes to protect transplanted βTC-tet cells from rejection, we developed a model utilizing BALB/c SCID mice. The immunodeficient state of these mice allowed transplantation of the βTC-tet cells into these tolerant mice whose immune system could be selectively reconstituted by adoptively transferring splenocytes from allogeneic mice. After BALB/c SCID mice were rendered diabetic by treatment with STZ, the mice were transplanted by i.p. injection with βTC-tet cells. By 3 to 4 weeks after transplantation, the SCID mice normalized their blood glucose levels (Fig. 1C). When the blood glucose in the transplanted mice normalized to between 100–150 mg/dl, doxycycline was added to the drinking water to halt proliferation of βTC-tet cells and prevent hypoglycemia.

Fig. 1.

βTC-tet cells correct diabetes in syngeneic C3HeB/FeJ or in BALB/c SCID mice, but not in allogeneic BALB/c recipients. (A) C3HeB/FeJ, (B) BALB/c, or (C) BALB/c SCID mice were rendered diabetic by treatment with STZ. Mice were then transplanted with 4×106 βTC-tet cells delivered by i.p. injection (week 1), and blood glucose was measured weekly.

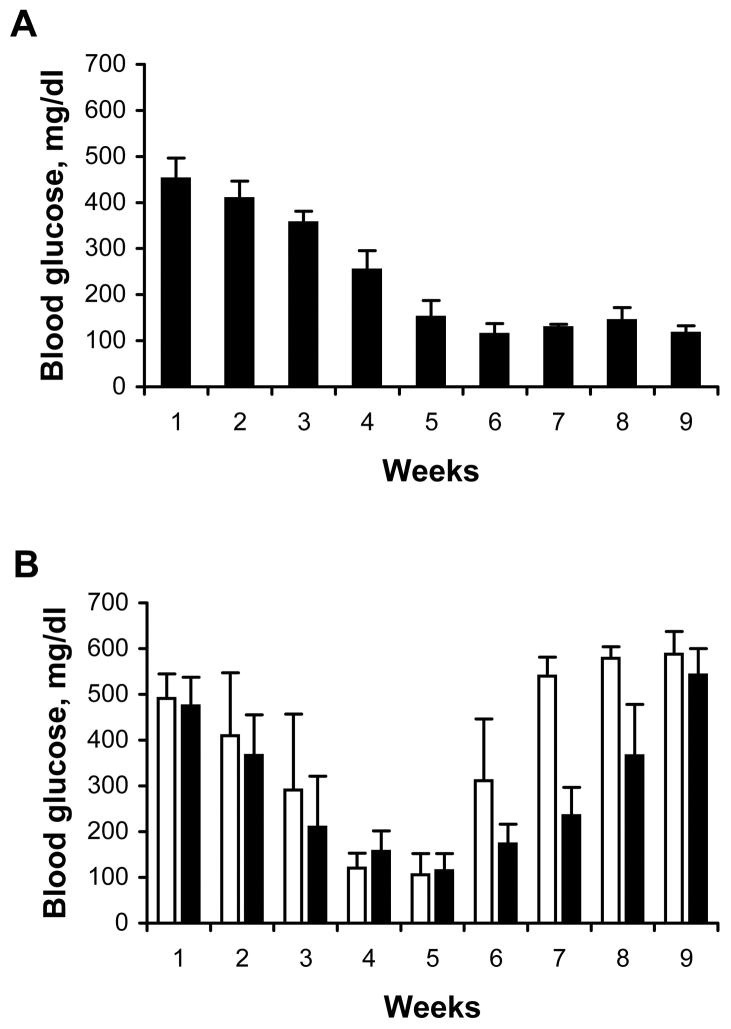

We next examined whether the islet cells transplanted into SCID mice would be rejected by adoptively transferred allogeneic leukocytes as indicated by the subsequent recurrence of hyperglycemia. Several days after normalization of the blood glucose, splenocytes obtained from C3HeB/FeJ mice (syngeneic with the βTC-tet cells), unprimed allogeneic BALB/c mice, or BALB/c mice primed by immunization with C3HeB/FeJ splenocytes, were injected i.v. into the mice. After the mice were injected with C3HeB/FeJ splenocytes, the blood glucose values remained at normoglycemic levels (<180 mg/dl) for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 2A). In contrast, hyperglycemia recurred in BALB/c SCID mice after adoptive transfer with allogeneic splenocytes (Fig. 2B). While recurrence of hyperglycemia occurred about 25 days after the mice were injected with unprimed allogeneic splenocytes, hyperglycemia recurred in almost half the time in mice injected with splenocytes from BALB/c mice primed with C3HeB/FeJ splenocytes (Fig. 2B). The accelerated onset of hyperglycemia when the transferred allogeneic splenocytes were isolated from primed mice indicated that the recurrence of hyperglycemia was due to immune-mediated depletion of the βTC-tet cells. These results validated the use of this model to test the capacity of lentiviral vectors to protect βTC-tet cells from immune-mediated rejection.

Fig. 2.

Hyperglycemia recurs in SCID mice transplanted with βTC-tet cells after adoptive transfer of allogeneic splenocytes. At week 1, diabetic BALB/c SCID mice were transplanted with βTC-tet cells (4×106 cells/mouse) by i.p. injection and blood glucose was monitored weekly. Approximately four weeks later when blood glucose had normalized, 3×107 splenocytes from (A) syngeneic C3HeB/FeJ mice, or from (B) unprimed BALB/c mice (black bars) or BALB/c mice primed by injection with C3HeB/FeJ splenocytes (white bars) were injected i.v. into transplanted SCID recipients. Blood glucose continued to be monitored weekly.

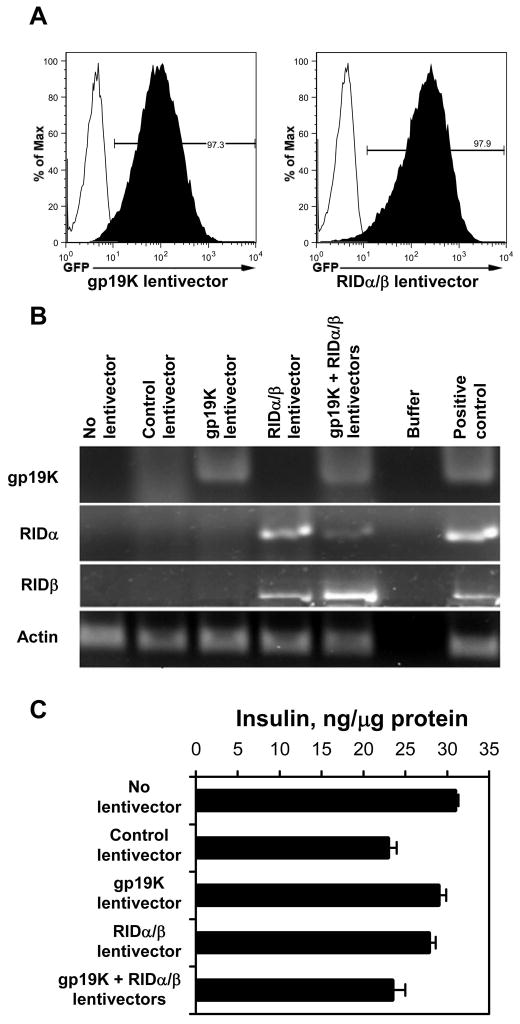

Lentiviral vectors efficiently introduce AdE3 genes into βTC-tet cells

We next examined whether expression of three genes from the AdE3 complex using third-generation lentiviral vectors, which efficiently transduce a wide range of cells and enable prolonged gene expression in the transduced cells and their progeny25, would be sufficient to prevent immune-mediated rejection of the βTC-tet cells. Adenoviruses extensively splice E3 transcripts to express the individual E3 proteins. Because lentiviruses lack the capacity to recapitulate this process, we constructed separate lentivectors expressing selected E3 proteins, specifically gp19K and RIDα/β. The RID complex is comprised of a 10.4 Kd α-chain and a 14.5 Kd β-chain, and its functional activity requires both chains. To express both proteins using a single lentiviral vector and promoter, we linked the genes encoding the RIDα and RIDβ chains with a sequence encoding a “self-cleaving” picornavirus 2A peptide that enables the stoichiometric production of two proteins from a single transcript24.

Lentivectors encoding either the gp19K or the RIDα and RIDβ proteins efficiently transduced the βTC-tet cells as evidenced by the expression of the GFP marker gene in 85–98% of the transduced βTC-tet cells (Fig. 3A). The expression of gp19K, RIDαand RIDβ mRNA by βTC-tet cells transduced with the corresponding lentivectors was detected by RT-PCR (Fig. 3B). Importantly, expression of the AdE3 genes by the lentiviral vectors did not compromise the capacity of the βTC-tet cells to synthesize insulin (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Transduction of βTC-tet cells with gp19K or RIDα/β lentiviral vectors carrying a GFP reporter gene. (A) To determine efficiency of transduction of βTC-tet cells with lentiviral vectors, flow cytometric analysis was performed 72 hours after transducing the βTC-tet cells with the gp19K or RIDα/β lentivector. The percentage of cells expressing the GFP reporter gene is indicated. (B) Expression of gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ mRNAs in the βTC-tet cells transduced with the indicated lentivectors was detected by RT-PCR using the indicated gene-specific primers. (C) βTC-tet cells transduced with the indicated lentivectors were lysed and their insulin content was measured by RIA. The data are shown as ng of insulin/μg cellular protein.

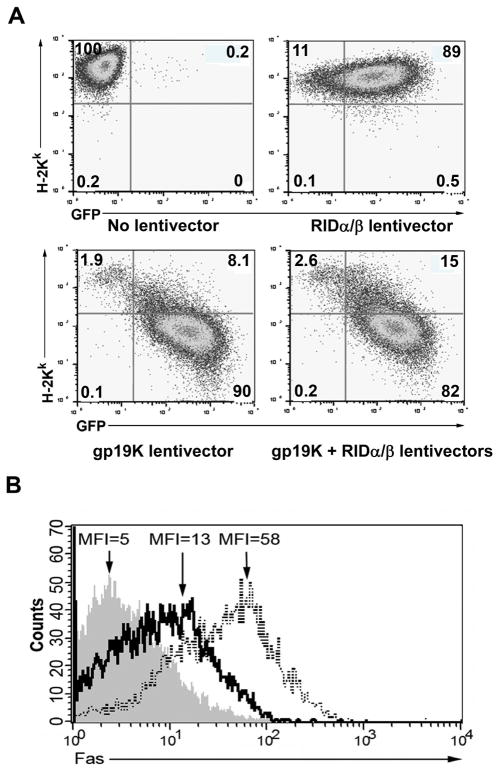

The gp19K and RIDα/β proteins expressed by transduced βTC-tet cells are functional

To evaluate the expression and function of lentiviral vector-encoded gp19K, we examined the βTC-tet cells transduced with the gp19K lentivector for gp19K-mediated downregulation of surface class I MHC. H-2Kk was reduced by over 90% in βTC-tet cells transduced with the gp19K lentivirus, but was unchanged in βTC-tet cells transduced with the RIDα-2A-RIDβ lentivector (Fig. 4A). The capacity of the gp19K lentivector to downregulate MHC expression was only marginally affected by co-transduction of the βTC-tet cells with the RIDα-2A-RIDβ lentivector. To evaluate efficient translation, cleavage, and function of the lentivector-encoded RIDα-2A-RIDβ protein, we examined the capacity of the RIDα-2A-RIDβ-encoding lentiviral vector to block IL-1β/TNF-α-stimulated surface expression of Fas, a member of the TNF superfamily that is a major mediator of T-cell killing and is involved in the allogeneic rejection and apoptosis of β cells26. Transduction of βTC-tet cells with the RIDα-2A-RIDβ-encoding lentiviral vector reduced by over 75% the cytokine-induced surface expression of Fas as compared to IL-1β/TNF-α-treated βTC-tet cells transduced with a control lentivector (Fig. 4B). Thus, taken together these results indicate that lentiviral vectors efficiently transduce βTC-tet cells and mediate expression of functional gp19K and RIDα/β proteins that exert their immunosuppressive effects.

Fig. 4.

Functional effects of lentivector-encoded gp19K and RIDα/β on βTC-tet cells. Cells were transduced with either gp19K or RIDα/β lentivectors (150 ng/1×105 cells), or co-transduced with both lentivectors (100 ng of each lentivector/1×105 cells). Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (A) Cell surface expression of class I MHC by βTC-tet cells was evaluated by staining of the cells with PE-conjugated anti-H-2Kk and analysis by flow cytometry 96 hours after transduction with the indicated lentivectors. Representative dot plots are shown wherein the transduced cells can be identified by GFP expression. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells in each quadrant. (B) The capacity of the RID lentivirus to downregulate surface Fas expression induced by overnight stimulation with TNF-α and IL-1β was evaluated by staining of the cells with PE-conjugated Fas and analysis by flow cytometry 96 hours after transduction. Gray histogram, isotype control; solid line, RIDα/β lentivector-transduced cells; dotted line, positive control of βTC-tet cells transduced with a lentivirus expressing GFP only.

Transduction with gp19K and RIDα/β lentivectors prior to transplantation protects βTC-tet cells from rejection by allogeneic immune effector cells

After hyperglycemia was induced in SCID mice by injection with STZ, the mice were injected with βTC-tet cells that were either co-transduced with lentivectors encoding gp19K and RIDα-2A-RIDβ or transduced with a control vector. After normalization of blood glucose, the mice were injected i.v. with primed BALB/c splenocytes. All of the mice injected with βTC-tet cells transduced with the control lentivector developed recurrence of hyperglycemia within 2–3 weeks after injection of primed splenocytes (Fig. 5A). In contrast, despite injection with primed allogeneic splenocytes, six out of the eight mice injected with βTC-tet cells transduced with the gp19K and RIDα-2A-RIDβ lentivectors remained diabetes-free for up to five months post-transplant (Fig. 5B). These results indicated that lentiviral vectors efficiently engineered βTC-tet cells to express gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ and protected transplanted cells from allogeneic rejection by the transferred primed BALB/c leukocytes.

Fig. 5.

Lentivector transduction with gp19K and RIDα/β prolongs control of hyperglycemia by transplanted βTC-tet cells in SCID mice after adoptive transfer of primed allogeneic splenocytes. βTC-tet cells were transduced with either (A) a control lentivector or (B) the lentivectors expressing gp19K and RIDα/β, and four days later the βTC-tet cells (6×106 cells/mouse) were injected i.p. into diabetic BALB/c SCID mice (week 1). When normoglycemia was achieved, splenocytes from primed BALB/c mice (3×107 cells) were injected i.v. In (B), six of the eight SCID mice transplanted with the AdE3-expressing cells maintained normoglycemia for over 20 weeks after splenocyte transfer (solid lines), while two mice became hyperglycemic within 4 weeks (broken lines). In (A) and (B), the horizontal line indicates a blood glucose value of 300 mg/dl.

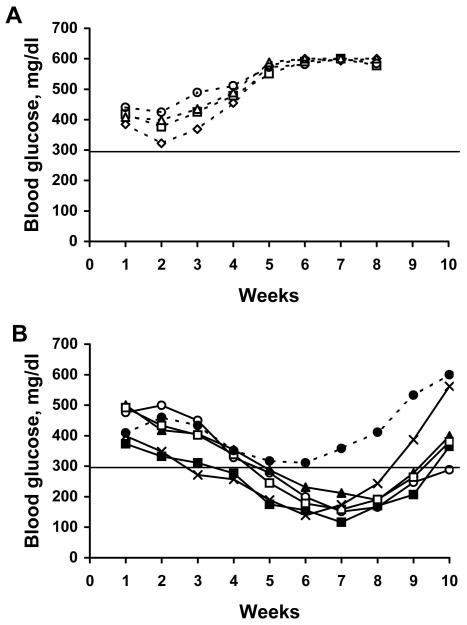

Lentiviral-mediated expression of gp19K and RIDα/β prolongs the ability of βTC-tet cells to correct hyperglycemia in diabetic allogeneic BALB/c mice

We examined whether lentiviral vector-mediated expression of gp19K, RIDα and RIDβ could protect βTC-tet cells from rejection after transplantation into an allogeneic host. After BALB/c mice were rendered diabetic with STZ, they were injected with βTC-tet cells that were either co-transduced with lentivectors encoding gp19K and RIDα-2A-RIDβ or transduced with a control lentivector. βTC-tet cells transduced with the control lentivector did not significantly alter the hyperglycemia in the mice (Fig. 6A). In contrast, transplanted βTC-tet cells co-transduced with the lentivectors encoding gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ successfully treated hyperglycemia in five of six BALB/c mice for up to eight weeks after transfer (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that expression of gp19K and RIDα/β can be sufficient to protect transplanted β cells from allorejection for this period of time even in animals with an intact immune system and in the absence of systemic immunosuppression.

Fig. 6.

βTC-tet cells transduced with gp19k and RIDα/β lentivectors, but not with a control lentivector, correct hyperglycemia after transplant into diabetic BALB/c mice. βTC-tet cells were transduced with either (A) a control lentivector or with (B) gp19K and RIDα/β lentivectors. Four days later the βTC-tet cells (7×106 cells/mouse) were injected i.p. into diabetic allogeneic BALB/c mice (week 1) and blood glucose was monitored. In (B), five of the six mice attained normoglycemia after transfer (solid lines), while only one did not (broken line). In (A) and (B), the horizontal line indicates a blood glucose value of 300 mg/dl.

DISCUSSION

Genetic engineering using lentiviral vectors enables the engineering of cells to decrease their susceptibility to allogeneic rejection after transplantation. Cellular transplantation of a variety of cell types (including hepatocytes, myoblasts, endothelial cells, neural cells, and chondrocytes) is being explored as a potential therapeutic strategy for a number of disease states1. Ex vivo genetic engineering of these cell types with lentiviral vectors encoding immunoprotective proteins could be used as a strategy to improve survival of grafts transplanted across allogeneic barriers. We tested the physiological implementation of this approach using a model of treating diabetes with transplanted insulin producing β cells. After islet transplantation into patients with type 1 diabetes, β cells are subject to elimination by both alloimmune and autoimmune responses3, necessitating the administration of potent immunosuppressive drug regimens having serious side effects2,5. The application of genetic engineering to modify β cells ex vivo prior to transplantation and protect them from immune destruction represents an attractive alternative approach that is being explored in multiple laboratories27–32. Here we demonstrate that lentiviral vector expression of three AdE3 proteins (gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ) is sufficient to prevent β cell allograft rejection and permit prolonged correction of hyperglycemia without the requirement for systemic immunosuppression. Lentiviral vector-mediated expression of gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ by β cells protects them from elimination by the immune system most likely by decreasing expression of class I MHC molecules and inhibiting cytokine-induced Fas upregulation (Fig. 4). AdE3 gp19K inhibits class I MHC-mediated antigen presentation by binding the MHC heavy chain and retaining it in a non-functional form in the endoplasmic reticulum12. It is unlikely that lentiviral vector reduction of class I MHC expression to prevent CTL killing will be sufficient to protect β cells from immune rejection, because of the reported important role of CD4+ T cells as well as innate immunity in islet allorejection33. For this reason, we engineered a lentiviral vector capable of expressing RIDα and RIDβ, in addition to gp19K, in the βTC-tet cells. The RIDαβ complex has been shown to inhibit FasL-induced cell death by downregulating Fas from the cell surface via a mechanism that involves Fas internalization and targeted degradation in the lysosome34. Lentiviral vector-mediated co-expression of gp19K, and RIDα and RIDβ was sufficient to protect transplanted βTC-tet cells from alloimmune destruction in most, but not all, recipients (Figs. 5B and 6B). Our ability to use third-generation lentivectors and a 2A linker to efficiently transduce β cells and express multiple proteins by a single vector will allow us to explore the possibility of adding other immunomodulatory proteins to our system. The lentiviral system provides the advantage of very high efficiency of transduction and stable integration with continued expression of the protective gene for prolonged periods of time without the limitations of vector toxicity27,35.

The model system we utilized for this study, diabetic SCID mice whose hyperglycemia is corrected by transplanted βTC-tet cells until they are rejected by transferred allogeneic leukocytes, provides a high throughput model for studying the in vivo impact of lentiviral vector-mediated genetic engineering to protect β cells from immune-mediated rejection, as well as for investigating the in vivo immune mechanisms of rejection. A major strength of the lentiviral vector system is that it can be extended in an iterative process to delineate the immune response genes critical for the triggering of immune-mediated rejection of β cells. The use of lentiviral vectors encoding siRNA constructs would enhance their capacity to inhibit specifically a range of immune response genes in the transplanted β cells and permit us to examine the impact of downregulating these genes on conferring resistance to β cell rejection after adoptive transfer of the transplanted SCID mice with defined populations of allogeneic leukocytes. Alternatively, we could also examine the effect of lentiviral vector-mediated overexpression of molecules such as PD-L136 which would deliver inhibitory signals to T cells and thereby protect transplanted cells from rejection. Such experiments would not only help in the definition of the molecular and cellular participants in β cell rejection, they might also suggest alternatives or adjunct genes to gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ for the lentiviral vector-mediated protection of transplanted β cells.

While we have shown that expression of gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ can protect transplanted β cells from alloimmune destruction, clinical translation to patients with type 1 diabetes will require that the lentiviral vector-encoded genes also protect the cells from autoimmune responses. NOD mouse studies demonstrated that transgenic expression of the entire AdE3 region by β cells could indeed protect them from autoimmune attack19,20. However, in mice transgenic for the expression of gp19K alone, or of a combination of RIDα/β and another adenoviral protein 14.7K, each conferred less protection from autoimmune destruction of islets than did expression of the entire E3 region19. Whether lentiviral vector-mediated co-expression of gp19K and RIDα/β will be sufficient to protect β cells from autoimmune attack remains to be determined. We will also need to explore whether an immune response will be generated against the lentiviral vector-delivered gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ themselves, which could lead to the undesired elimination of the lentiviral-vector transduced β cells. However, we are encouraged by the report that inclusion of the AdE3 complex in an Ad-based gene therapy vector resulted in inhibition of cytotoxic activity against Ad-infected cells, as well as a diminished humoral response to viral proteins37.

A further challenge is indicated by our finding that allogeneic recipients of AdE3-expressing βTC-tet cells experience a recurrence of their diabetes at ten weeks post-transplant (Fig. 6B). One explanation for these findings is that the expression of the AdE3 proteins declines over time, and so the βTC-tet cells eventually become vulnerable to immune rejection. An alternative explanation is that expression of gp19K and RIDα/β in combination is simply insufficient to protect βTC-tet cells indefinitely from alloimmune rejection. Unfortunately, it is not possible to discriminate between these two explanations experimentally in our system, as cells injected into the peritoneal cavity cannot be quantitatively recovered. Furthermore, it is, of course, not possible to measure the E3 expression of cells that have already been eliminated. Alternative systems will need to be devised to investigate these important issues. Further investigation will also need to address the finding that transplantation of transduced βTC-tet cells did not reverse diabetes in all recipients in the presence of transferred or endogenous allogeneic leukocytes (Figs. 5B and 6B). All of the animals shown in Fig. 5B received the same batch of transduced βTC-tet cells, as did all of the recipients in Fig. 6B. Thus, within each experiment, all should have received comparable numbers of cells expressing the AdE3 proteins and at comparable levels. It is possible, however, that AdE3 expression levels were altered in vivo such that they varied from one recipient to another. For the technical reasons just described, we could not determine whether the ineffectiveness of a transplant correlated with reduced expression of the AdE3 proteins in vivo in individual recipients. The variability in clinical response may reflect instead, or in addition, variable immune function from one recipient to another.

The shortage of human islet donors is one of our motivations for examining the capacity of lentiviral vectors to genetically engineer isolated β cells rather than intact islets. Our long-term goal is to use lentiviral vectors to engineer β cells capable of producing insulin in a glucose-regulated manner that can be transplanted into diabetic individuals and correct hyperglycemia without requiring treatment with immunosuppressive agents. The murine βTC-tet cell line is well-differentiated, has a stable phenotype, and maintains normal regulated insulin secretion in both growth-arrested and growing cells22,23. However, concerns associated with xenotransplantation38 make it unlikely that these lentiviral vector-encoded murine cells will be used to treat humans. As reviewed39, in order to obtain human β cells for transplantation into patients, multiple groups are attempting to produce β cells from embryonic stem cells or from stem/progenitor cells isolated from human fetal liver, adult pancreas, or other adult organs. Encouraging results have been obtained from at least some of these approaches40,41. Once a reliable source of human β cells becomes available, our findings suggest that lentiviral vectors can be used to genetically engineer β cells to express gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ prior to transplantation and eliminate or markedly reduce the requirement for potent immunosuppressive regimens. This approach can be readily applied to protect any transplanted cell population from allogeneic rejection thereby reducing the need for the immunosuppressive agents currently necessary for transplantation protocols and would greatly expand the application of cellular transplantation as a therapeutic approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and animals

βTC-tet cells, derived from C3HeB/FeJ mice (H-2k) and previously described22,23, were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; 4.5 g/L glucose) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The 293T cells used for generation of the lentivectors were maintained in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. BALB/c SCID mice (H-2d) were bred at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (AECOM) and housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility at AECOM. C3HeB/FeJ and BALB/c mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and bred inhouse. Animal experiments complied with the Animal Welfare Act and NIH Guidelines for the Ethical Care and Use of Animals in Biomedical Research and were approved by the AECOM Institute for Animal Studies.

Transplantation protocol

Female mice 8–10 weeks of age were injected with 200 mg/kg streptozotocin (STZ) intraperitoneally (i.p.). Blood glucose was monitored (One Touch Ultra; offscale readings are reported as 600 mg/dl) until the animals became diabetic (>300 mg/dl on two separate occasions). βTC-tet cells were trypsinized, washed and resuspended in PBS, and then injected i.p. into diabetic mice. When blood glucose reached 100–150 mg/dl, doxycycline (2 mg/ml) was added to the drinking water to arrest the growth of the transplanted cells.

Priming of immune effectors and adoptive transfer of splenocytes

For priming, splenocytes from C3HeB/FeJ mice were isolated, purified by density centrifugation over Ficoll, and 2×107 splenocytes were injected subcutaneously into immunocompetent BALB/c mice. Two to three weeks later, splenocytes from primed mice were purified and injected i.v. into transplanted SCID mice (3 × 107 cells/mouse) and blood glucose was monitored weekly.

Generation and production of lentiviral vectors

Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) pseudotyped, HIV-1-based, third-generation lentiviruses25, one expressing gp19K, amplified by PCR from Ad2E3/pcDNA337, and the other expressing the RIDα and RIDβ genes, amplified by PCR from Ad2 RIDα/pcDNA3 and Ad2 RIDβ/pcDNA3 plasmids, respectively, and linked with a 2A peptide (RIDα-2A-RIDβ)24, were generated by calcium phosphate-mediated co-transfection of 293T cells with four plasmids: a CMV promoter-driven packaging construct expressing the gag and pol genes, an RSV promoter-driven construct expressing rev, a CMV promoter-driven construct expressing the VSV-G envelope, and a self-inactivating transfer construct driven by the hPGK promoter containing the HIV-1 cis-acting sequences and an expression cassette for either gp19K or the RIDα-2A-RIDβ coding sequence inserted upstream of an IRES-regulated GFP24. Control (GFP only) lentivirus was generated by transfecting 293T cells expanded in 10 cm tissue culture plates with the packaging, Rev-expressing, Env-expressing and the basal expression constructs in the presence of calcium phosphate. The culture media was replaced 12 to 16 hours after transfection, and the supernatant was collected, filtered, and concentrated by ultracentrifugation (50,000 × g for 2.5 hours) 24 and 48 hours later. The viral pellet was resuspended in sterile PBS and frozen in aliquots at −80°C until use. The concentration of the lentiviruses was determined by measurement of p24 in the supernatant by ELISA. The βTC-tet cells were transduced by lentivectors as described42 Briefly, the βTC-tet cells were resuspended in 0.5 ml of complete IMDM with added polybrene (4 μg/mL) and plated into 24 well plates (1×105 cells/well). The indicated lentiviral vector (100 ng of p24) was added to each well, the plates were centrifuged (2,500 rpm for 1 hour) and incubated overnight at 37°C. The next day complete IMDM was added to each well and incubated for an additional 5 days. Transduction efficiency and gene expression were determined by flow cytometry as described below.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed with an LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and FlowJo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR) was utilized for data analysis. βTC-tet cells were stained with an antibody to H-2Kk class I MHC (CTKk; Serotec) or with an antibody to mouse Fas (Jo2; BD Biosciences). For the latter, the cells were stimulated with mTNF-α (100 ng/ml) and mIL-1β (10 ng/ml) overnight prior to harvesting and staining. Subsequent staining steps were performed on ice. Pellets were washed twice in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS and incubated in FACS buffer (FB; 2% FBS in PBS) for 10 min on ice. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 100 μl of FB with specific antibody or the corresponding isotype control and incubated for 30–45 min. Cells were washed twice in FB then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS prior to analysis. Cells were then analyzed for GFP and PE by gating on the viable βTC-tet cell population by forward and side scatter and then compensating using FlowJo software.

RT-PCR

βTC-tet cells were infected with the indicated lentivectors for five days and total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent and quantitated by OD at 260 nm. After treatment with RNAse-free DNAse, RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified using the OneStep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The primer pairs for mRNA transcript detection used were 5′-CTATTTGGCAGCCAGGTGACACTA-3′ and 5′-GCTGTAATAAGCAGAGCGGTGGAA-3′ (202 bp product), 5′-CATCATGGATCCCATGATTCCTCGAGTTC-3′ and 5′-CACAGTCGACTTAAAGAATTCTGAG-3′ (275 bp product), 5′-CATCATGGATCCCATGAAACGGAGTGTC-3′ and 5′-CACAGTCGACTCAGTCATCTCCACCTG-3′ (392 bp product) for gp19K, RIDα, and RIDβ transcripts, respectively. A mouse actin primer pair (5′-TCGTACCACAGGCATTGTGATGGA-3′ and 5′-TGATGTCACGCACGATTTCCCTCT-3′ (199 bp product) was used to confirm mRNA integrity. The amplified products were detected by size fractionation on an ethidium bromide-stained gel.

Assessment of insulin content of βTC-tet cells

Four to six days after plating cells in 12-well culture dishes (5 × 105 cells/well), the cells were washed twice with PBS and 1 ml of 3 M acetic acid was added to each well. The cells were harvested, sonicated twice for 20 sec, centrifuged at 1000×g and the supernatant was lyophilized and reconstituted in 0.1% BSA in PBS. Insulin levels were determined using an insulin-specific RIA43.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases P01DK52956 and P60DK20541 and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AI67136 and the Einstein/MMC Center for AIDS Research AI51519).

Footnotes

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No competing financial interests exist for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Edge AS. Current applications of cellular xenografts. Transplant Proc. 2000;32:1169–1171. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)01170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan EA, Paty BW, Senior PA, Bigam D, Alfadhli E, Kneteman NM, et al. Five-year follow-up after clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2005;54:2060–2069. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balamurugan AN, Bottino R, Giannoukakis N, Smetanka C. Prospective and challenges of islet transplantation for the therapy of autoimmune diabetes. Pancreas. 2006;32:231–243. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000203961.16630.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nir T, Melton DA, Dor Y. Recovery from diabetes in mice by β cell regeneration. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2553–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI32959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, Auchincloss H, Lindblad R, Robertson RP, et al. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1318–1330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horwitz MS. Function of adenovirus E3 proteins and their interactions with immunoregulatory cell proteins. J Gene Med. 2004;6 (Suppl 1):S172–183. doi: 10.1002/jgm.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benedict CA, Norris PS, Prigozy TI, Bodmer JL, Mahr JA, Garnett CT, et al. Three adenovirus E3 proteins cooperate to evade apoptosis by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor-1 and -2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3270–3278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gooding LR, Ranheim TS, Tollefson AE, Aquino L, Duerksen-Hughes P, Horton TM, et al. The 10,400- and 14,500-dalton proteins encoded by region E3 of adenovirus function together to protect many but not all mouse cell lines against lysis by tumor necrosis factor. J Virol. 1991;65:4114–4123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4114-4123.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shisler J, Yang C, Walter B, Ware CF, Gooding LR. The adenovirus E3-10.4K/14.5K complex mediates loss of cell surface Fas (CD95) and resistance to Fas-induced apoptosis. J Virol. 1997;71:8299–8306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8299-8306.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman JM, Horwitz MS. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced NF-κB activation by the adenovirus E3-10.4/14.5K complex. J Virol. 2002;76:5515–5521. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5515-5521.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delgado-Lopez F, Horwitz MS. Adenovirus RIDαβ complex inhibits lipopolysaccharide signaling without altering TLR4 cell surface expression. J Virol. 2006;80:6378–6386. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02350-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgert HG, Maryanski JL, Kvist S. “E3/19K” protein of adenovirus type 2 inhibits lysis of cytolytic T lymphocytes by blocking cell-surface expression of histocompatibility class I antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1356–1360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beilke J, Johnson Z, Kuhl N, Gill RG. A major role for host MHC class I antigen presentation for promoting islet allograft survival. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:1173–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sigrist S, Ebel N, Langlois A, Bosco D, Toso C, Kleiss C, et al. Role of chemokine signaling pathways in pancreatic islet rejection during allo- and xenotransplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3516–3518. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eizirik DL, Mandrup-Poulsen T. A choice of death--the signal-transduction of immune-mediated beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetologia. 2001;44:2115–2133. doi: 10.1007/s001250100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Santamaria P. Dissecting autoimmune diabetes through genetic manipulation of non-obese diabetic mice. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1447–1464. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Efrat S, Fejer G, Brownlee M, Horwitz MS. Prolonged survival of pancreatic islet allografts mediated by adenovirus immunoregulatory transgenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1995;92:6947–6951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efrat S, Serreze D, Svetlanov A, Post CM, Johnson EA, Herold K, et al. Adenovirus early region 3 (E3) immunomodulatory genes decrease the incidence of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2001;50:980–984. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce MA, Chapman HD, Post CM, Svetlanov A, Efrat S, Horwitz M, et al. Adenovirus early region 3 antiapoptotic 10.4K, 14.5K, and 14.7K genes decrease the incidence of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2003;52:1119–1127. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Herrath MG, Efrat S, Oldstone MB, Horwitz MS. Expression of adenoviral E3 transgenes in β cells prevents autoimmune diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1997;94:9808–9813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine BL, Humeau LM, Boyer J, MacGregor RR, Rebello T, Lu X, et al. Gene transfer in humans using a conditionally replicating lentiviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2006;103:17372–17377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efrat S, Fusco-DeMane D, Lemberg H, al Emran O, Wang X. Conditional transformation of a pancreatic β-cell line derived from transgenic mice expressing a tetracycline-regulated oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1995;92:3576–3580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleischer N, Chen C, Surana M, Leiser M, Rossetti L, Pralong W, et al. Functional analysis of a conditionally transformed pancreatic β-cell line. Diabetes. 1998;47:1419–1425. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.9.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Dilioglou S, Vanin EF, et al. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Follenzi A, Naldini L. Generation of HIV-1 derived lentiviral vectors. Methods Enzymol. 2002;346:454–465. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)46071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrovsky N, Silva D, Socha L, Slattery R, Charlton B. The role of Fas ligand in beta cell destruction in autoimmune diabetes of NOD mice. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;958:204–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dupraz P, Rinsch C, Pralong WF, Rolland E, Zufferey R, Trono D, et al. Lentivirus-mediated Bcl-2 expression in βTC-tet cells improves resistance to hypoxia and cytokine-induced apoptosis while preserving in vitro and in vivo control of insulin secretion. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1160–1169. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallichan WS, Kafri T, Krahl T, Verma IM, Sarvetnick N. Lentivirus-mediated transduction of islet grafts with interleukin 4 results in sustained gene expression and protection from insulitis. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2717–2726. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grey ST, Arvelo MB, Hasenkamp W, Bach FH, Ferran C. A20 inhibits cytokine-induced apoptosis and nuclear factor κB-dependent gene activation in islets. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1135–1146. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.8.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machen J, Bertera S, Chang Y, Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Robbins PD, et al. Prolongation of islet allograft survival following ex vivo transduction with adenovirus encoding a soluble type 1 TNF receptor-Ig fusion decoy. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1506–1514. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papeta N, Chen T, Vianello F, Gererty L, Malik A, Mok YT, et al. Long-term survival of transplanted allogeneic cells engineered to express a T cell chemorepellent. Transplantation. 2007;83:174–183. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000250658.00925.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabinovitch A, Suarez-Pinzon W, Strynadka K, Ju Q, Edelstein D, Brownlee M, et al. Transfection of human pancreatic islets with an anti-apoptotic gene (bcl-2) protects β-cells from cytokine-induced destruction. Diabetes. 1999;48:1223–1229. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lunsford KE, Gao D, Eiring AM, Wang Y, Frankel WL, Bumgardner GL. Evidence for tissue-directed immune responses: analysis of CD4- and CD8-dependent alloimmunity. Transplantation. 2004;78:1125–1133. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000138098.19429.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elsing A, Burgert HG. The adenovirus E3/10.4K-14.5K proteins down-modulate the apoptosis receptor Fas/Apo-1 by inducing its internalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1998;95:10072–10077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobinger GP, Deng S, Louboutin JP, Vatamaniuk M, Matschinsky F, Markmann JF, et al. Transduction of human islets with pseudotyped lentiviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:211–219. doi: 10.1089/104303404772680010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keir ME, Francisco LM, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in T-cell immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilan Y, Droguett G, Chowdhury NR, Li Y, Sengupta K, Thummala NR, et al. Insertion of the adenoviral E3 region into a recombinant viral vector prevents antiviral humoral and cellular immune responses and permits long-term gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1997;94:2587–2592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravelingien A. Xenotransplantation: the ethical and legal concerns. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14:653–654. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Efrat S. Beta-cell replacement for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sapir T, Shternhall K, Meivar-Levy I, Blumenfeld T, Cohen H, Skutelsky E, et al. Cell-replacement therapy for diabetes: Generating functional insulin-producing tissue from adult human liver cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2005;102:7964–7969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405277102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zalzman M, Gupta S, Giri RK, Berkovich I, Sappal BS, Karnieli O, et al. Reversal of hyperglycemia in mice by using human expandable insulin-producing cells differentiated from fetal liver progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2003;100:7253–7258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1136854100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joseph A, Zheng JH, Follenzi A, Dilorenzo T, Sango K, Hyman J, et al. Lentiviral vectors encoding human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T-cell receptor genes efficiently convert peripheral blood CD8 T lymphocytes into cytotoxic T lymphocytes with potent in vitro and in vivo HIV-1-specific inhibitory activity. J Virol. 2008;82:3078–3089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01812-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Ambra R, Surana M, Efrat S, Starr RG, Fleischer N. Regulation of insulin secretion from β-cell lines derived from transgenic mice insulinomas resembles that of normal β cells. Endocrinology. 1990;126:2815–2822. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-6-2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]