A recent Journal article1 found language preference was often unassociated, and English proficiency was consistently associated, with self-rated health—implying these should be modeled separately. A reexamination of this study suggests the reported conclusions depended on erroneous measures and highlights the importance of validity in linguistic studies.

Two alternative linguistic indicators, which have stronger face validity, were examined alongside the self-reports used in the original study in a replication using the same National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) data. Interviewers rated respondents’ English proficiency as non-English speaking, poor, fair, good, or excellent, and this was used to assess the criterion validity of self-reported language proficiency. Stronger preferences for English should be associated with conducting the survey in English; hence, the survey language measure was used to assess the predictive validity of self-reported language preference. A combined index was computed by standardizing interviewers’ reports of English proficiency and conducting the interview in English—so each item weighed equally in the final index—and then summing the resulting quotients (Cronbach α = 0.78). These items were then tested in separate models predicting the 5 categorizations of self-rated health, replicating the original model specification, using ordinal logistic regression. (A complete methodological appendix is available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.)

All interviewer-rated non-English speakers were misclassified; 75% reported they spoke poor, 18% fair, and 7% good English. This misclassification persisted where overlapping categorization between interviewer and self-reports existed. Among respondents with poor English proficiency, for example, 28% reported fair and 7% good English speaking proficiency. Overestimation tendencies also interfered with self-reported preferences. About 18% of non-English speakers reported using some English, 7% equal parts English and their native language, and 3% mostly English with friends. Respondents who reported speaking only English with friends versus mostly their native language had similar tendencies to interview in English (18% and 17%, respectively). The strong reliability originally reported with other self-reported measures for which no alternative existed, e.g., reading proficiency, suggests these may be similarly biased.

Valérie Boyer has proposed legislation in France that would require all digitally altered photographs of people used in advertising to be labeled as retouched. Boyer, with a background in health administration and 2 adolescent daughters, became interested in the pressures on adolescents and young women to match the fashionable ideal of a thin body and perfect skin upon reflection as a mother. Photograph by Francois Guillot/Agence France-Presse. Printed with permission of Getty Images.

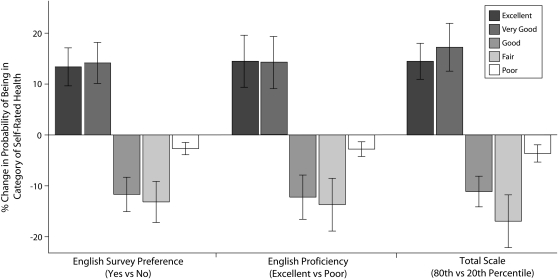

Behavioral measures of English proficiency, preference, and their combined scale, contrary to the original study, had similar significant associations with self-rated health) Figure 1). For example, surveying in English versus surveying in another language was associated with a 13% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 10, 17) higher probability of excellent health and a corresponding 4% (95% CI = 2, 5) lower probability of poor health. Standardized coefficients were computed to compare the relative effect size across measures, given the variation in measurement units. English proficiency, (B = −0.57; 95% CI = −0.73, −0.42), preference, (B = −0.52; 95% CI = −0.71, −0.34), and their combined scale (B = −0.70; 95% CI = −0.88, −0.52), had statistically indistinguishable associations with self-rated health.

FIGURE 1.

Change in probability of self-rated health by English language differences in survey preference, proficiency, and their combined scale.

Note. Each set of probabilities indicates a separate regression with adjustment for education, ethnicity, gender, region of the US in which respondents resided, age, and social desirability.

It is well known that self-reports are susceptible to large systematic biases,2 yet many studies have relied on self-reported linguistic measures. Among the 15 observational studies in the Journal since 1999 that used acculturation, acculturative, or acculturated in their title or abstract 10 (67%)3–12 relied entirely on self-reported linguistic measures and only 3 (20%)13–15 included observed linguistic traits. Public health has been strongly critical of biomedical models16; however, when it comes to measures, a biomedical perspective in which the validity of survey measures are assumed appears common. The possible biases that interfered with the replicated study1 may similarly impact other studies, especially those that relied entirely on self-reported measures. The reasons are many, but in addition to being a health determinant, English may be perceived as relevant to social status and respondents will be tempted to overestimate their English traits. Self-reports may also be limited because of poor across-subject reliability, where self-reports are under- or overestimated relative to direct observation.

It is admirable that Gee et al.1 have conducted research on measurement issues in acculturative studies, but their conclusions are questionable given the systematic error in their primary measures. Future research should instead focus on the validity of linguistic measures by refining-observational measures that overcome the limitations of self-reports. Studies focused on enhancing the reliability and validity of interviewer observed linguistic measures are needed. Given the deviations of self-reports from face valid alternatives, it is advisable to apply similar strategies, as explored here, to other studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by federal student work study aid and the National Institutes of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (RC1-AA018970-01).

I would like to thank C. Richard Hofstetter, David Holtgrave, Melbourne Hovell, Carl Latkin, and Keith Schnakenberg for helpful comments.

Human Participant Protection

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health's institutional review board approved this study.

References

- 1.Gee GC, Walsemann KM, Takeuchi DT. English proficiency and language preference: testing the equivalence of two measures. Am J Public Health 2010;100(3):563–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaller J. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Malley AS, Kerner J, Johnson AE, Mandelblatt J. Acculturation and breast cancer screening among Hispanic women in New York City. Am J Public Health 1999;89(2):219–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alderete E, Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Lifetime prevalence of and risk factors for psychiatric disorders among Mexican migrant farmworkers in California. Am J Public Health 2000;90(4):608–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Carter-Pokras O, Andersen R. Acculturation and leisure-time physical inactivity in Mexican American adults: results from NHANES III, 1988-1994. Am J Public Health 2001;91(8):1254–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pérez-Stable EJ, Ramirez A, Villareal R, et al. Cigarette smoking behavior among US Latino men and women from different countries of origin. Am J Public Health 2001;91(9):1424–1430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honda K. Factors associated with colorectal cancer screening among the US urban Japanese population. Am J Public Health 2004;94(5):815–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez SL, Kelsey JL, Glaser SL, Lee MM, Sidney S. Immigration and acculturation in relation to health and health-related risk factors among specific Asian subgroups in a health maintenance organization. Am J Public Health 2004;94(11):1977–1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkinson AV, Spitz MR, Strom SS, et al. Effects of nativity, age at migration, and acculturation on smoking among adult Houston residents of Mexican descent. Am J Public Health 2005;95(6):1043–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Detjen MG, Nieto FJ, Trentham-Dietz A, Fleming M, Chasan-Taber L. Acculturation and cigarette smoking among pregnant Hispanic women residing in the United States. Am J Public Health 2007;97(11):2040–2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz GD, Chen Y, Salazar CR, Le Geros RZ. The association of immigration and acculturation attributes with oral health among immigrants in New York City. Am J Public Health 2009;99(Suppl 1):S474–S480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shelley D, Fahs M, Scheinmann R, Swain S, Qu J, Burton D. Acculturation and tobacco use among Chinese Americans. Am J Public Health 2004;94(2):300–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brett KM, Higgins JA. Hysterectomy prevalence by Hispanic ethnicity: evidence from a national survey. Am J Public Health 2003;93(2):307–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vega WA, Sribney WM, Achara-Abrahams I. Co-occurring alcohol, drug, and other psychiatric disorders among Mexican-origin people in the United States. Am J Public Health 2003;93(7):1057–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin MA, Shalowitz MU, Mijanovich T, Clark-Kauffman E, Perez E, Berry CA. The effects of acculturation on asthma burden in a community sample of Mexican American schoolchildren. Am J Public Health 2007;97(7):1290–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav 1995;35(extra issue):80–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]