Abstract

This qualitative study explored whether motherhood plays a role in influencing decisions to conceal or reveal knowledge of seropositive status among women living with HIV/AIDS in 2 South African communities: Gugulethu and Mitchell's Plain. Using the PEN-3 cultural model, we explored how HIV-positive women disclose their status to their mothers and how HIV-positive mothers make decisions about disclosure of their seropositive status. Our findings revealed 3 themes: the positive consequences of disclosing to mothers, how being a mother influences disclosure (existential role of motherhood), and the cost of disclosing to mothers (negative consequences). The findings highlight the importance of motherhood in shaping decisions to reveal or conceal knowledge of seropositive status. Implications for interventions on HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and support are discussed.

The literature on the experiences and factors that influence disclosure of HIV seropositive status among women in many developed countries is quite extensive.1–9 However, in sub-Saharan African countries like South Africa where the prevalence of HIV remains high,10 there is scant evidence on the disclosure experiences of women. Inevitably, the available evidence fails to explore the broader contextual factors that influence women's decisions to conceal or reveal their seropositive status. For example, Makin et al.11 explored individual factors that influence disclosure among pregnant women in South Africa, but it remains unclear whether collective contexts such as mother–daughter relationships or aspects of motherhood (i.e., the desire to nurture and protect children, and so on) play a critical role in influencing women's decisions to disclose. A better understanding of factors such as the concept of motherhood is essential to understanding how women disclose and cope with living with their seropositive status. Moreover, such insights could help advance and focus public health intervention efforts to reduce HIV- and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination, prevent new HIV infections, promote effective care, and support strategies for mothers and women living with HIV and AIDS.

The discourse on notions of motherhood in sub-Saharan Africa in general and in South Africa in particular has long been a subject of interest to many researchers over the decades. Previous studies have described motherhood as a form of collective identity, the analysis of which is useful in understanding not only the critical role the mother plays in a child's welfare but also the roles and expectations of being mothers.12–15 Two aspects of motherhood are examined in this study. First, what is most unstated about motherhood is that it is a lifelong commitment—one remains a child to one's mother regardless of one's age.13,16 Mothers play a crucial role not only as birth givers but also as life givers, as one needs one's mother at every turn in life.13 Second, as Magwaza noted, “mothering is not only about children but also the mothers who are involved in the actual practice.”17(p14) Because child care is often the sole responsibility of mothers, there is a generally held view that all mothers are expected to provide emotional care and support for their children. However, in some cases it is not uncommon to have “contradictions between what societies expect of mothers and what mothers themselves do”17(p14) (as in the case of mothers abusing their children).

Kruger noted that the discourse on motherhood is much more complex than simply describing “mothering practices as either fulfilling/successful or difficult/problematic.”18(p196) Instead, it is important to note that the act of mothering may entail different meanings to different women and that these meanings are often influenced by the historical, sociocultural, and economic contexts of the women who are doing the mothering.18 In the context of HIV and AIDS disclosure, it is imperative to understand these different meanings of motherhood (particularly as women living with HIV and AIDS try to decide whether to reveal or conceal their seropositive status) as well as issues related to emotional care, support, stigma, and discrimination.

In South Africa, the discourse on motherhood cannot be separated from the history of institutional discrimination that occurred within South Africa, particularly during apartheid. The apartheid era was a critical period in South Africa that led to forced removals and dislocations of families and communities and also weakened families’ capacities to care for their family members.17,19 Apartheid, alongside various interrelated racial, ethnic, historical, political, and socioeconomic circumstances, also influenced the nature and characteristics of mothering practices in South Africa.17,19–21

Although it is important to take ethnic differences (such as being African, Indian, or Colored) into account when contextualizing motherhood in South Africa, there is minimal evidence on how mothering practices differ across ethnicities. The existing literature highlights similarities in mothering practices between ethnicities as related to nurturing and providing care for family members. For example, Magwaza17 noted that among African mothers, informal adoptions were on the rise. Much of the task of providing basic needs such as education, food, and clothing to relatives were carried out by these mothers, “who did not consider themselves as mothers to their biological children only.”17(p7) Field has argued that Colored mothers are viewed “not only as the maternal head of the family, but also the moral authority of the family,”21(p64) noting that even in male-headed households, these mothers often assume the central role of disciplining, teaching, and nurturing the children. Colored mothers are expected to teach their children ideals related to preserving the dignity of their households.

The significance of mothers as nurturers as well as symbols of moral authority and dignity21 within families has particular relevance in the context of the HIV and AIDS epidemic in South Africa, as young women now account for about 90% of new HIV infections.22,23 Given the burden of HIV and AIDS alongside the legacy of apartheid, it is possible that the combination of these factors may affect traditional and societal expectations of mothering practices in South Africa, particularly in the context of disclosing seropositive status.

We expand the current literature on disclosure of HIV/AIDS status among women in South Africa by exploring whether motherhood plays a role in influencing decisions to conceal or reveal knowledge of seropositive status. In particular, we explored how HIV-positive women disclose their status to their mothers and how HIV-positive mothers make decisions about disclosure of their seropositive status. Because motherhood in general occupies an important focus around which individual and collective identities are structured,13 we suggest that it can provide an anchor on which people living with HIV and AIDS can gain emotional care, support, and acceptance as well as buffer the negative factors associated with HIV and AIDS infection, such as stigma and discrimination. We also argue that the critical but often obscure position of mothers can serve as a useful guide for exploring the factors that influence decisions on disclosure of seropositive status. Given that issues surrounding HIV and AIDS disclosure are central to notions of identity, expectations, and belongingness, we explored the context of motherhood within disclosure of HIV and AIDS status using the PEN-3 cultural model developed by Airhihenbuwa.12,24,25

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

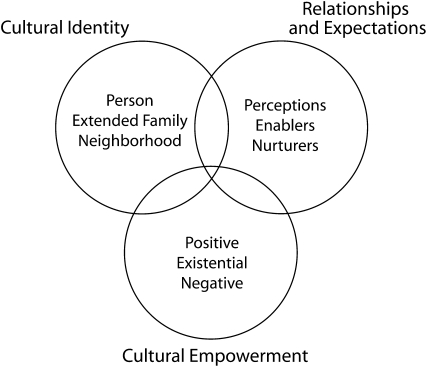

The PEN-3 cultural model addresses health behaviors from a collective rather than an individual perspective (Figure 1).25 It has been used to guide a cultural approach to HIV and AIDS in Africa,26–28 as well as to examine the influence of culture in nutrition practices29,30 and to explore cultural constructs in cancer-related research.31–33

FIGURE 1.

The PEN-3 cultural model.

The PEN-3 model focuses on contextual domains of culture that influence health beliefs and actions.12 This model proposes that cultural appropriateness in health promotion should not focus only on the individual, but instead on the context that nurtures a person and his or her family and community.12 The model consists of 3 dynamically related dimensions: (1) cultural identity, (2) relationships and expectations, and (3) cultural empowerment.12

In the first dimension, cultural identity, the model does not assume that all interventions should be focused solely on the individual; instead, it extends the focus to incorporate extended family and neighborhood contexts in identifying the intervention point of entry that addresses the context of behavior change. In the second dimension, relationships and expectations, the model posits that the construction and interpretation of behaviors are usually based on the interaction between the perceptions people have about the behavior, the resources and institutional forces that enable or disenable actions, and the influence of family, kin, friends, and—most importantly—culture in nurturing the behavior.

With the third dimension, cultural empowerment, factors that are critical to behavioral change are evaluated for attributes that are positive, existential (i.e., unique), and negative. Of particular interest to this study is the domain of cultural empowerment. Specifically, in this study, we use the cultural empowerment domain to explore (1) whether the consequences of disclosing to mothers are positive, (2) whether there are unique aspects of motherhood that influence disclosure (existential roles of motherhood), and (3) the negative responses that arise as a result of disclosing one's seropositive status to one's mother.

METHODS

This study was part of a 5-year capacity-building project that uses the PEN-3 model as a cultural framework for exploring HIV and AIDS stigma in South Africa. The project's goal was to examine contextual factors that may contribute to HIV- and AIDS-related stigma in the community in general and in the family and health care settings in particular. Focus group methodology and in-depth interviews with key informants were used to explore HIV and AIDS stigma. These qualitative methods were used to better understand the meaning of stigma in South Africa and specifically the ways in which stigma manifests in different subpopulations, with a particular focus on the impact on women. Focus groups are ideal in this setting as they facilitate open discussions in ways that allow participants to express their views, including the opportunity to elaborate on comments made by members. In-depth interviews with key informants allow participants to address a range of issues as individuals. The combination of different approaches to qualitative data collection helps to achieve a deeper understanding of the contexts of stigma.34,35

In this report, we focus specifically on focus groups and individual in-depth interviews conducted with women living with HIV and AIDS during the second year of the project. These women were from 2 communities in the Western Cape: Gugulethu (a Black South African community) and Mitchell's Plain (a predominantly Colored community). Focus groups and in-depth interviews conducted with other family and community members during the second year of data collection were excluded from this report. Our use of focus groups allowed participants living with HIV and AIDS to openly discuss issues that they felt were important relative to disclosure. Because only women living with HIV and AIDS participated in the focus group discussions described here, our participants were probed on the unique aspects of their own disclosure experiences.

Participants

A purposive sampling approach was used to identify and recruit eligible participants (n = 48) for the focus groups (n = 7) and in-depth interviews (n = 6) conducted during the second year of data collection. Participants were recruited from HIV and AIDS support groups in Gugulethu and Mitchell's Plain. Although participants varied in age, most were single and never married and lived in the semi-urban areas of Gugulethu and Mitchell's Plain. The size of the focus groups ranged from 5 to 7 participants, whereas the in-depth interviews were conducted with individual participants. The groups only met once. Participants were recruited and interviewed by trained postgraduate students at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa. These students, with the aid of research assistants, also conducted the focus group discussions. Participants were informed of the study objectives and read and signed an informed consent form.

Focus Group and In-Depth Interview Guide

We focus here only on the questions on disclosure that were posed to all participants. Specifically, we asked participants to describe their experiences with disclosure of seropositive status. Participants were asked, “Who was the first person that you shared news of your status with? Why did you choose that person? What was the reason behind your disclosure?” Probes were used in the focus groups and in-depth interviews as required. Each focus group interview was conducted either in English, Xhosa, or Afrikaans, the 3 predominant languages spoken in the Western Cape. The focus groups and the in-depth interviews were audio-taped with the participants’ permission. Focus groups and in-depth interviews conducted in Xhosa and Afrikaans were first transcribed and then translated into English.

Data Analysis

All data collected from the discussions were loaded into Nvivo 2.0 qualitative software to facilitate management of the data. Nvivo is a qualitative software program that aids in organizing data collected from qualitative research.36 The data analyzed for this study used the 4 processes described by Morse and Field: comprehension, synthesizing (decontextualization), theorizing, and recontextualization.37 As described by Morse and Field, the process of data analysis facilitates comprehension.37 Specifically, through coding the data, Morse and Field were able to sort the data to uncover underlying meanings in the text. Intraparticipant microanalysis (line-by-line analysis) of the interviews allowed them to identify patterns of experiences that were salient to HIV/AIDS disclosure.37 When data were synthesized, composite descriptions of the factors that influenced HIV/AIDS disclosure in conjunction with specific examples from the data were generated through interparticipant analysis (comparison of transcripts from focus groups and in-depth interviews).

In theorizing qualitative studies, Morse and Field suggested that theories are “essential tools, critical to all methods of inquiry, particularly with qualitative research,” and that “without theories, qualitative research would be without structure and application, and disconnected from the greater body of knowledge.”37(p128) Thus, in this study, different explanations were continuously and rigorously selected and revised until the best explanations that fit the data were developed. The final outcome of this process was the development of 3 themes that provided the most comprehensive and coherent method of theorizing the influence of motherhood on disclosure of HIV seropositive status among women in South Africa.

Morse and Field suggested that the goal of recontextualization is to place the results in the context of established knowledge.37 In this study, the established cultural empowerment domain of the PEN-3 cultural model played a critical role as it provided the context used to advance knowledge on women's disclosure of HIV seropositive status within the context of motherhood in South Africa.

RESULTS

Sixteen women in the focus groups and 2 women in the in-depth interviews reported that they had disclosed their seropositive status first to their mothers. Of the remaining 30 participants, 9 reported that they had initially disclosed their status to other family members (such as their children, sisters, brothers, aunts, and uncles), 7 initially disclosed to their boyfriends, 6 disclosed to their friends, and 8 participants did not reveal to whom they initially disclosed. It is important to note that our findings are mostly participants’ accounts of what happened during and after disclosure, and how their mothers treated them afterward. Overall, our focus groups and in-depth interviews revealed that there could be both positive and negative consequences associated with disclosure to mothers, and that being a mother herself could influence a participant's decision to disclose.

Positive Consequences of Disclosing to Mothers

Participants who disclosed to their mothers said that they acted out of an inherent belief that “there is no one but her” and that “she is the best one” to whom to reveal the news of their HIV seropositive status. They expressed the belief that mothers “won't chase” their children away and that they would give them the “necessary support” for living with HIV and AIDS. Although people often consider friends and other loved ones to be primary confidants to whom they should reveal sad news, the reality of HIV evokes an awakening of the pivotal location of mothers in times of difficulty, particularly in helping participants to live with knowledge of their seropositive status. As one participant remarked,

OK, I for one I decided to tell my mother because they ask you at the clinic as to who are you going to tell as your confidante. People have a tendency of taking for granted that question, and the frequent response would be my boyfriend … or sometimes my friend, and all along this is a serious question…. You start to think again as to “who should I tell,” then that is where you think of your mother as the only person who can seriously succumb and take you out of the problem.

The position of mothers became more indispensable as the women dealt with the knowledge of their seropositive status. Some participants emphasized that disclosure was borne out of an inherent trust in motherhood, as they knew that their mothers would protect them. In particular, one participant remarked,

I don't know, maybe it was because she's a mother and I know she's always trying to protect and I don't know who else I must tell because I trusted my mother. And I just think she must be the first person to know these things.

It was common for mothers to express sadness and disappointment after hearing the news. However, many of the participants indicated that their mothers were very supportive afterward. As one participant stated, “When I told my mother she was a bit upset but afterwards she was supportive.” Another participant said,

My mother was frightened and she was equally disappointed but she gave me the necessary support because there was nothing she could do and I ended up accepting my status.

For many participants, disclosure to their mothers brought about their own acceptance of their seropositive status. Mothers were supportive in terms of wanting to learn more about HIV and AIDS in order to help their children. As one participant expressed it,

My mother was very supportive as she came with me to find out more about HIV and AIDS and how she could assist me with whatever things I need…. We used to have the support group at our place and that also showed that she accepted the fact that I'm HIV positive. She always wants to learn more about my sickness.

In addition, mothers were central to providing a medium through which participants shared the news of their seropositive status with the rest of their family. Our focus group interviews revealed that, in situations in which participants struggled with revealing their seropositive status, mothers served as mediators. Thus, a mother's knowledge is implied to be collective (family) knowledge; mothers represent the conduit through which emotional balance is sought because they know whom to contact and in which order, and at what point to inform other family members. This finding is clearly exemplified in the words of a participant:

She encouraged and counseled me, saying that I shouldn't worry, “I'll always be by your side.” She called the family members, cousins, and they told me I shouldn't worry, they will help me with everything I need.

Existential Roles of Motherhood

Our focus group discussions and in-depth interviews revealed that for some participants who were mothers themselves, the disclosure of seropositive status was linked to their existential (unique) roles as mothers. As one participant remarked,

But for us as women it's difficult because if you test positive today you won't keep it for yourself for a long time. Because it's gonna work on you, you see your children, you see your husband, you see your family so it's working on you so you'd rather come out [and reveal your status].

Because motherhood is often linked with numerous roles and responsibilities, it was inherently difficult for mothers in our study to keep knowledge of their seropositive status to themselves, particularly given the sense of responsibility they felt toward their children. Sometimes, a supportive and encouraging professional may offer advice that reinforces desire to disclose, as described by one participant:

So I went for counseling at the clinic. I started to speak that I couldn't keep it to myself; I knew that I would have to open up. And when the counselor said that I must talk to my children, the first one I spoke to was the eldest one.

The practices expected of mothers were another crucial factor that influenced disclosure. In South Africa, most women discover their HIV status during routine antenatal testing, which is available through programs such as prevention of mother-to-child transmission.38 These women are then faced with the pressure of having to disclose not only to their partners39 but also to family members,40 particularly female elders who often manage pregnancy and childbirth. After childbirth, the female elders tend to look after the young mother, ensuring that she adheres to traditional caring and feeding practices. Culturally, advice on breastfeeding is a conduit through which older women offer vital lessons in motherhood to young mothers.12 In the context of HIV disclosure, this cultural expectation that mothers will breastfeed becomes a challenge as mothers struggle to reconcile the need to protect their children from possible HIV infection through breastfeeding with the emotional consequences of not disclosing and lying about why they choose not to breastfeed. As one participant said,

I told my mother I got this [HIV-positive] status because she asked why don't I breastfeed the baby. The first time I lied and the second time I told myself I'm sick and tired of lying.

Negative Consequences of Disclosing to Mothers

As mentioned in the introduction, the apartheid regime, along with racial and socioeconomic contexts, have influenced the notion of motherhood in South Africa. Mothering practices have also endured changes brought on by forced dislocations and removals from relatives and communities. Since the dawn of the HIV and AIDS epidemic, family spheres have encountered dramatic changes, particularly in the context of motherhood, as women of childbearing age now account for 90% of new HIV infections.22,23 It is possible, then, that the burden of HIV and AIDS, along with the related increased mortality rates, may play a role in altering or eroding traditional expectations in mothering practices in South Africa, particularly as these relate to nurturing one's children.

Although our focus group and in-depth interviews revealed that disclosing HIV serostatus to mothers often had positive consequences, some participants experienced negative consequences. Some mothers did not conform to generally held views about being a mother. For one participant, disclosure of seropositive status was unsettling as it led to disruptions in her relationship with her mother. As she explained,

We were like sisters, very close and shared everything; and everything just changed. We can't get into a conversation without getting into an argument, and at first it wasn't there. We had a very open relationship, me and my mother … even after I've got married and even after I had my first children we were still the same. It was only after I told her that I was positive that things started changing…. There were times that she would get the police and lock me up, and I would be very frustrated with this, just knowing that I've got this virus and then she would throw me out with my kids.

Disclosure to mothers was particularly problematic for some participants who found that their mothers resorted to drinking as a coping mechanism for dealing with their children's status. Thus, even when mothers were not being supportive of their daughters, some of their coping behaviors indicated that they continued to feel personally responsible for what had happened to their daughters. Although maternal drinking has been previously cited as a problem in the Western Cape region of South Africa,41–44 in our study it was a major consequence of a daughter's HIV disclosure. As one participant said, “My mother, on the other hand, when I told her she got drunk, it is almost like she wants to drink this problem away.”

Because mothers are expected to provide emotional care and support for their children, daughters’ disclosure of seropositive status led to a sense of helplessness, resulting in some cases in self-destructive behavior. The following participant's description is illustrative:

After disclosing in 2004 [to her mother that she was HIV positive] … what happened was she got drunk, and after getting drunk she actually swore at me and said, “You must leave my house, take [your] clothes and go, I don't want you here in my house. You've got AIDS and you gonna give us AIDS” and that was 2 o'clock in the morning and then at 7 I got up, packed my clothes and I went to stay with a friend of mine.

HIV and AIDS have further altered the African notion that the ill are the responsibility of the collective, represented by the mother. Thus, HIV seropositive status has weakened the hitherto nurturing and protective nature of mothering practices. Breastfeeding, as a powerful conduit through which young women learn lessons about motherhood from female elders in the family, is an existential factor that influences disclosure of seropositive status. As mothers try to balance the preventive practices expected of persons living with HIV/AIDS status with the collective expectations of breastfeeding, some find themselves having to make decisions that may increase the risk of their baby being infected. One participant spoke of having to negotiate between the expectations of breastfeeding and disclosure of her HIV status:

You know how grandmothers are, she wanted me to breastfeed and I did not know how. I would even start to explain to my grandmother why I was not breastfeeding, I gave her excuses that there is something wrong with my breast or the child is full. I would give excuses but I found that she is forcing me to breastfeed the child and I know that she does not know the situation I am in. I cannot tell her this, and this is what is happening.

For this woman, the desire not to disclose, even in the face of the mothering expectations of breastfeeding, weighed heavily against her desire to protect her baby against possible HIV infection. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study conducted in Johannesburg, South Africa, which highlighted how mothers often engaged in elaborate strategies, sometimes unnecessarily, to justify to family members their avoidance of breastfeeding.45

DISCUSSION

We explored the factors that influence disclosure of HIV and AIDS among women living in South Africa. Using the PEN-3 cultural model, we found that notions of motherhood were central in shaping decisions to conceal or reveal HIV seropositive status. They highlighted the positive consequences and unique aspects of motherhood that promote disclosure while drawing attention to the negative consequences. Although most of the 48 participants did not disclose first to their mothers, this may be indicative of fear of disappointing one's mother, particularly given the stigma associated with HIV. Furthermore, in aligning with the guiding principles of the cultural empowerment domain, rather than focusing simply on the negative consequences of disclosure as revealed in this study, there is a need to address and recognize the positive consequences and existential aspects12 of disclosure so as to better inform public health interventions to reduce HIV- and AIDS-related stigma, discrimination, and rejection.

In our study, motherhood was important in shaping decisions regarding disclosure of HIV seropositive status in the following ways. First, there was an inherent belief that mothers would not “chase” their daughters away when they revealed their seropositive status, and that they would provide “necessary support” for living with HIV. Indeed, as evidenced by the responses of some participants, it was generally felt that the position of mothers was important partly because it provided support for living with HIV in numerous ways. Mothers enabled participants to accept their status, and they helped them to learn more about HIV and AIDS. Our results confirm previous findings in South Africa that mothers were usually a source of support after their daughters’ disclosure of HIV seropositive status.46,47 Additionally, our findings revealed that mothers represented a medium through which participants disclosed news of their HIV status to the rest of their families.

Second, the unique aspects of being a mother were an important factor that shaped women's decisions surrounding disclosure of their HIV seropositive status. This finding reinforced the findings of Smith et al. that threats to health are not independent of a person's social or familial context.48 Given the numerous roles and responsibilities of motherhood, most mothers living with HIV and AIDS expressed the difficulty and challenge of keeping knowledge of seropositive status to themselves. Our focus groups and in-depth interviews revealed that reasons for disclosure among mothers living with HIV and AIDS often centered on expectations of the mother as a nurturer (i.e., breastfeeding, protecting children).

Finally, our findings indicate that a daughter's disclosure of HIV status to her mother sometimes acted to disrupt relationships between the two. It was also found that some mothers engaged in drinking after hearing the news, which was indicative of the responsibility and burden that they felt even when they were not supportive. As one participant remarked, it was almost as if her mother wanted to drink knowledge of her seropositive status away. In addition, among daughters who were also mothers, there was an internal struggle as they tried to balance their desire not to transmit AIDS through breastfeeding with traditional mothering expectations. Similar findings were reported by Doherty et al.,38 who noted that for HIV-positive mothers, the challenges and difficulties of mothering often revolved around an internal struggle between preventing infant HIV infection and yielding to deep-rooted family and community norms regarding breastfeeding. It was common for mothers to hide the truth about their HIV status and to provide excuses for engaging in nonnormative breastfeeding practices.38

Together, our findings shed light on the often obscure agency of motherhood as a pivotal family locus influencing disclosure of women's HIV status in South Africa. The findings probe how mother–daughter relationships and aspects of being mothers influence disclosure of status. In this study, exploring HIV/AIDS disclosure within the context of motherhood draws attention to the critical role of mothers in shaping decisions to disclose as well as in addressing acceptance of seropositive status, care, and support needs of women living with HIV and AIDS. Despite some negative consequences of disclosing to mothers, the role of motherhood is an important consideration for interventions aiming to provide care and support for women living with HIV and AIDS. For example, given the fact that the HIV- and AIDS-related stigma remains a major problem in South Africa, closer attention to the contextual factors that influence HIV-related stigma is needed.

Consideration of all aspects of the total context, such as the pivotal position of mothers as a source of “necessary support” for those living with HIV and AIDS, might aid public health researchers in developing interventions to reduce or eliminate stigma. Also, among mothers living with HIV, the fact that prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV necessitates disclosure is an important context that warrants further attention, as better understanding of infant-feeding practices among HIV-positive mothers is critical in the design of interventions aimed at improving not only infant feeding but also child survival.38 At a time when HIV-related stigma is reported to remain a major factor in fueling the pandemic, it is important to explore not only the negative contextual factors that trigger the occurrence of stigma, but also the positive and unique factors that are equally important in efforts to reduce stigma.2

Limitations

This study has some notable limitations. First, discussion of one's seropositive status is a potentially sensitive topic; as a result, some of the participants may have been less open about sharing their experiences with disclosure. Indeed, 8 participants in our study chose not to reveal their experiences. Although we acknowledge that our findings may be limited because of varying degrees of openness by participants, the use of focus groups (alongside in-depth interviews) was essential in allowing participants living with HIV and AIDS to share their experiences and provide a deeper understanding of the central role of motherhood in managing this pandemic. They openly and freely discussed aspects of their disclosure experiences, which would have been impossible using a survey instrument. Keeping in mind that in-depth interviews are ideal for potentially sensitive topics, we found that focus groups of people sharing and experiencing the same health conditions are ideal in that they give others the confidence to delve deeply into aspects of their own experiences. Focus groups allowed us to cross-check and compare some of the findings we observed in our in-depth interviews.

Second, our focus group and in-depth interviews did not delve deeply into cultural pressures in the form of the societal expectations of motherhood that are central to decisions to conceal or reveal knowledge of seropositive status. This should be a priority area for further studies.

Third, even though the relatively small sample size was adequate for this qualitative study, the results should not be considered representative of women living with HIV and AIDS in South Africa. We argue that in qualitative research and, in particular, focus group and in-depth interviews, small numbers of participants are ideal because they encourage participants to interact freely and to deeply express their feelings, attitudes, opinions, and experiences.49 The sample size chosen for this study adequately fulfilled the research aim.50 It also enabled the investigators to substantively elucidate the process by which women disclose knowledge of their HIV seropositive status.

Fourth, despite our finding that mothers were frequently the first person to whom HIV-positive women disclosed their status, several participants did not initially reveal their status to their mothers, perhaps through fear of disappointing them. However, of the participants who disclosed to their mothers, the common theme that emerged was the pivotal importance of motherhood in shaping decisions to disclose HIV seropositive status.

Finally, caution should also be exercised in generalizing these findings to other geographical locations, as our interpretation of the notions of motherhood may not be applicable in other settings. Although we focused on the disclosure experiences of women, future studies should also explore the experiences of men living with HIV and AIDS to address whether the role of the collective contexts (such as fatherhood) is important in shaping individual decisions regarding disclosure of HIV seropositive status.

Conclusions

Motherhood is an important departure point for addressing issues related to disclosure of HIV seropositive status by women living with HIV and AIDS. A notable finding in our study was the widespread recognition that notions of motherhood were indispensable to the disclosure of HIV seropositive status, particularly as it enabled participants to garner acceptance and support for living with HIV and AIDS. Future interventions, however, may consider anchoring public health efforts in motherhood to addressing the difficulties surrounding disclosure among HIV-positive women. Our findings show the importance of motherhood in the care and support of individuals with HIV/AIDS. Indeed, awareness and understanding of the centrality of motherhood in disclosure of HIV seropositive status is particularly important to health care professionals because it has the potential to greatly improve their efforts to address the care, support, and management needs of people living with HIV and AIDS. Finally, a deeper appreciation of motherhood should contribute to our knowledge of the contexts for developing new HIV prevention interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (grant R24 MH068180).

We thank the following students for participating in data collection: Vuyisile Mathiti, Heidi Wichman, Tshipinare Marumo, Shahieda Abrahams, Thandiwe Chihana, Nashrien Khan, Roro Makubalo, Xolani Nibe, Gail Roman, Matlakala Pule, and Nadira Omarjee.

Human Participant Protection

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of Pennsylvania State University and the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

- 1.Sowell RL, Seals BF, Phillips KD, Julious CH. Disclosure of HIV infection: how do women decide to tell? Health Educ Res 2003;18(1):32–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armistead L, Tannenbaum L, Forehand R, Morse E, Morse P. Disclosing HIV status: are mothers telling their children? J Pediatr Psychol 2001;26(1):11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy DA, Steers WN, Dello Stritto ME. Maternal disclosure of HIV serostatus to their young children. J Fam Psychol 2001;15(3):441–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gielen AC, Fogarty L, O'Campo P, Anderson J, Keller J, Faden R. Women living with HIV: disclosure, violence, and social support. J Urban Health 2000;77(3):480–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serovich JM, Kimberly JA, Greene K. Perceived family member reactions to women's disclosure of HIV-positive information. Fam Relat 1998;47:15–22 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gielen AC, O'Campo P, Faden RR, Eke A. Women's disclosure of HIV status: experiences of mistreatment and violence in an urban setting. Women Health 1997;25(3):19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sowell RL, Lowenstein A, Moneyham L, Demi A, Mizuno Y, Seals BF. Resources, stigma, and patterns of disclosure in rural women with HIV infection. Public Health Nurs 1997;14(5):302–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moneyham L, Seals B, Demi A, Sowell R, Cohen L, Guillory J. Experiences of disclosure in women infected with HIV. Health Care Women Int 1996;17(3):209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simoni JM, Mason HR, Marks G, Ruiz MS, Reed D, Richardson JL. Women's self-disclosure of HIV infection: rates, reasons and reactions. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63(3):474–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behavior and Communication Survey: A Turning Tide Among Teenagers Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makin JD, Forsyth BW, Visser MJ, Sikkema KJ, Neufeld S, Jeffery B. Factors affecting disclosure in South African HIV-positive pregnant women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2008;22(11):907–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Airhihenbuwa CO. Healing Our Differences—The Crisis of Global Health and the Politics of Identity Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oyeronke O. Abiyamo: theorizing African motherhood. Jenda 2003;4:1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amadiume I. Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society London, England: Zed Books; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nzegwu NK. Family Matters: Feminist Concepts in African Philosophy of Culture Albany: State University of New York Press; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker C. Conceptualizing motherhood in twentieth century South Africa. J South Afr Stud 1995;21(3):417–437 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magwaza T. Perceptions and experiences of motherhood: a study of black and white mothers of Durban, South Africa. J Cult Afr Women Stud 2003;(4):1–14 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motherhood Kruger L. In: Shefer TB, Bezuidenthout F, Kiguwa P, eds. The Gender of Psychology Cape Town, South Africa: Juta Press; 2006:182–195 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bozalek V. Contextualizing care in black South African families. Soc Polit 1999;6:85–99 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lesch E, Anthony L. Mothers and sex education: an explorative study in a low-income Western Cape community. Acta Academica 2007;39(3):129–151 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Field S. Sy Is die Baas van die Huis: women's position in the coloured working class family. Agenda 1991;9:60–70 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rehle T, Shisana O, Pillay V, Zuma K, Puren A, Parker W. National HIV incidence measures—new insights into the South African epidemic. S Afr Med J 2007;97(3):194–199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS Sub-Saharan Africa AIDS epidemic update: regional summary. 2007. Available at: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/JC1526_epibriefs_subsaharanafrica_en.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2009

- 24.Airhihenbuwa CO. Health and Culture: Beyond the Western Paradigm Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Airhihenbuwa CO, Webster D. Culture and Africa contexts of HIV/AIDS prevention, care and support. SAHARA J 2004;1(1):1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petros G, Arihihenbuwa CO, Leickness S, Ramalagan S, Brown B. HIV/AIIDS and “othering” in South Africa: the blame goes on. Cult Health Sex 2006;8(1):67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwelunmor J, Airhihenbuwa CO, Okoror TA, Brown DC, Belue R. Family systems and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Int Q Community Health Educ 2006–2007;27(4):321–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Airhihenbuwa CO, Okoror TA, Shefer TS, et al. Stigma, culture, and HIV and AIDS in the Western Cape, South Africa: an application of the PEN-3 Cultural Model for community based research. J Black Psychol 2009;35(4):407–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kannan S, Webster D, Sparks A, et al. Using a cultural framework to assess the nutrition influences in relation to birth outcomes among African American women of childbearing age: application of the PEN-3 theoretical model. Health Promot Pract 2009;10(3):349–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James DC. Factors influencing food choices, dietary intake, and nutrition-related attitudes among African Americans: application of a culturally sensitive model. Ethn Health 2004;9(4):349–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abernethy AD, Magat MM, Houston TR, Arnold HL, Jr., Bjorck JP, Gorsuch RL. Recruiting African American men for cancer screening studies: applying a culturally based model. Health Educ Behav 2005;32(4):441–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erwin DO, Johnson VA, Feliciano-Libid L, Zamora D, Jandorf L. Incorporating cultural constructs and demographic diversity in the research and development of a Latina breast and cervical cancer education program. J Cancer Educ 2005;20(1):39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis RK. Using a culturally relevant theory to recruit African American men for prostate cancer screening. Health Educ Behav 2005;32(4):452–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of Qualitative Research Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 36.NVivo 2.0: Using NVivo in Qualitative Research (Computer Software & Manual) Melbourne, Australia: QSR International; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative Research Methods: Health Professional Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doherty T, Chopra M, Nkonki L, Jackson D, Greiner T. Effect of the HIV epidemic on infant feeding in South Africa: when they see me coming with the tins they laugh at me. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84(2):90–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varga C, Brooks H. Preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission among South African adolescents. J Adolesc Res 2008;23(2):172–205 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seidel G, Sewpaul V, Dano B. Experiences of breastfeeding and vulnerability among a group of HIV-positive women in Durban, South Africa. Health Policy Plan 2000;15(1):24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viljoen DL, Phillip Gossage J, Brooke L, et al. Fetal alcohol syndrome epidemiology in a South African community: a second study of a very high prevalence area. J Stud Alcohol 2005;66(5):593–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.May PA, Phillip Gossage J, Brooke L, et al. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol syndrome in the Western Cape Province of South Africa: a population-based study. Am J Public Health 2005;95(7):1190–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viljoen D, Croxford J, Phillip Gossage J, Kodituwakku PW, May PA. Characteristics of mothers of children with fetal alcohol syndrome in the Western Cape Province of South Africa: a case control study. J Stud Alcohol 2002;63:6–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adnams CM, Kodituwakku PW, Hay A, Molteno CD, Viljoen D, May PA. Patterns of cognitive-motor development in children with fetal alcohol syndrome from a community in South Africa. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25(4):557–562 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Varga CA, Sherman GG, Maphosa J, Jones SA. Psychosocial consequences of early diagnosis of HIV status in vertically exposed infants in Johannesburg, South Africa. Health Care Women Int 2005;26(5):387–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ncama BP. Acceptance and disclosure of HIV status through an integrated community/home-based care program in South Africa. Int Nurs Rev 2007;54(4):391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almeleh C. Why do people disclose their HIV status? Qualitative evidence from a group of activist women in Khayelitsha. Soc Dyn 2006;32(2):136–169 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith RA, Ferrara M, Witte K. Social sides of health risks: stigma and collective efficacy. Health Commun 2007;21(1):55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berg B. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marshall MN. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam Pract 1996;13(6):522–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]