Abstract

The nonmetropolitan mortality penalty results in an estimated 40 201 excessive US deaths per year, deaths that would not occur if nonmetropolitan and metropolitan residents died at the same rate. We explored the underlying causes of the nonmetropolitan mortality penalty by examining variation in cause of death. Declines in heart disease and cancer death rates in metropolitan areas drive the nonmetropolitan mortality penalty. Future work should explore why the top causes of death are higher in nonmetropolitan areas than they are in metropolitan areas.

Persistent spatial clusters of metropolitan and nonmetropolitan differences in mortality1 and in life expectancy2 exist in the United States and in European countries.3 Research indicates that the historical metropolitan mortality penalty—higher rates of death in cities than in rural areas—has been reversed since the mid 1980s. Now, nonmetropolitan areas have higher all-cause mortality rates than do metropolitan areas.4 We explored cause-specific mortality rates in the United States from the last 40 years and determined that the relatively recent nonmetropolitan mortality penalty is largely a result of changes in place-specific rates of death from heart disease and cancer, although there have been no changes in the ratio of metropolitan-to-nonmetropolitan mortality rates associated with strokes.

METHODS

The National Center for Health Statistics Compressed Mortality File reports the number of deaths by age, race, sex, county of residence, and cause of death. We calculated annual all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates between 1968 and 2005.5 Cause-specific rates were calculated for the top 3 causes of death: heart disease, cancer, and stroke. Rates were expressed as deaths per 100 000 and were age adjusted (to the 2000 standard million) to permit comparisons across 2 county types (metropolitan and nonmetropolitan). International Classification of Diseases codes associated with each cause are outlined in Figure 1. Standardization by sex and race was unnecessary because they resulted in the same general pattern.9 Nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties were defined according to the US Department of Agriculture rural–urban continuum Beale codes, with the same definitional protocol as for the previously reported nonmetropolitan mortality penalty.4 Rates also were calculated with the county held constant as either metropolitan or nonmetropolitan for the duration of the analysis period; trends were comparable. Rate and excess death projections for 2010 and 2015 were calculated on the basis of the annual rate of change between 1986 (the point of the all-cause mortality crossover) and 2005.

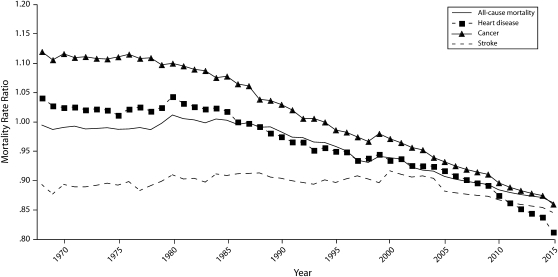

FIGURE 1.

Metropolitan-to-nonmetropolitan mortality rate ratio: National Center for Health Statistics Compressed Mortality File, 1968–2015.

Note. Heart disease deaths were included if the International Classification of Diseases, Adapted for Use in the United States, Eighth Revision (ICDA-8),6 recode was between 310 and 400 (1968–1978), if the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9),7 recode was between 320 and 410, or if the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10),8 recode was between 53 and 68. Comparable recodes for stroke were 410 to 480 (ICDA-8), 420 to 490 (ICD-9), and 70 to 75 (ICD-10). For cancer deaths, the recodes were 15 to 240 (ICDA-8), 160 to 250 (ICD-9), and 19 to 44 (ICD-10).

RESULTS

Figure 1 depicts temporal trends in the metropolitan and nonmetropolitan mortality rate ratio from 1968 through 2005. Although a nonmetropolitan penalty has been associated with strokes for the last 40 years, the all-cause mortality penalty historically was associated with metropolitan residency. The all-cause nonmetropolitan mortality penalty first appeared in the mid-1980s, coinciding with the heart disease nonmetropolitan mortality penalty. The cancer nonmetropolitan mortality penalty did not appear until the mid-1990s.

The ratio of metropolitan to nonmetropolitan cancer mortality rates has declined consistently and at a slightly steeper rate than have declines in the heart disease mortality ratio over the past 20 years. By contrast, the stroke ratio has indicated persistently higher nonmetropolitan mortality over the last 30 years. Given these differences in trajectory, we plotted projections of the ratios through 2015 and estimated the excessive deaths associated with living in nonmetropolitan areas.

The 2005 mortality rates for metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas showed 9421 excessive deaths annually—deaths that would not have occurred if metropolitan rates were applied to nonmetropolitan residents—associated with heart disease. If that trend continues, excessive heart disease deaths will increase to 11 993 by 2010 and 14 472 by 2015. In nonmetropolitan areas in 2005, cancer was associated with 6798 excess deaths annually; rates were estimated to increase to 10 392 by 2010 and 13 920 by 2015 if current trajectories continue. Nonmetropolitan excessive annual stroke deaths were fairly stable (approximately 4000). From all causes of death, 40 201 excessive deaths occurred annually in nonmetropolitan areas (2005), which should increase to 50 623 by 2010 and 60 654 by 2015 based on recent trends. However, excessive deaths associated with heart disease and cancer will account for half of the excessive deaths in nonmetropolitan areas by 2015.

DISCUSSION

Underlying reasons for changes in trends associated with the metropolitan-to-nonmetropolitan ratio, whether for all-cause mortality or for specific causes, are currently unknown. Possible contenders include changes in standards of care that were not implemented in nonmetropolitan areas to the same extent as in metropolitan areas, changes in rates of uninsurance, changes in disease incidence, and changes in health behaviors, but none of these would account for the nonmetropolitan mortality penalty unless they occurred at different rates in metropolitan areas than in rural areas.

Future research will need to examine the potential for period effects that may have led to these shifts, such as changes in treatment of heart disease or cancer. For stroke, in which timely medical treatment is more critical than it is for cancer, distance to a hospital may have led to the persistent nonmetropolitan mortality penalty (this also could apply to heart disease). Future research also should address the increasing Hispanic population, particularly Hispanic people living in rural areas, and their role in this emerging nonmetropolitan mortality penalty; however, the Compressed Mortality File precludes these analyses because the Hispanic variable was only recently added to the file. Further investigation is necessary to determine what has changed in the metropolitan and nonmetropolitan environments to cause a century-long trend—the all-cause metropolitan mortality penalty—to reverse.

Acknowledgments

No funding was used to support this research.

Human Participant Protection

Approval was granted by the Mississippi State University institutional review board.

References

- 1.Cossman JS, Cossman RE, James WL, Campbell CR, Blanchard TC, Cosby AG. Persistent clusters of mortality in the United States. Am J Public Health 2007;97:2148–2150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJL, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C, et al. Eight Americas: investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States [published erratum appears in PLoS Med. 2006;3(12):e545] PLoS Med 2006;3(9):e260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw M, Orford S, Brimblecombe N, Dorling D. Widening inequality in mortality between 160 regions of 15 European countries in the early 1990s. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1047–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosby AG, Neaves TT, Cossman RE, et al. Preliminary evidence for an emerging nonmetropolitan mortality penalty in the United States. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1470–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Health Statistics Compressed Mortality File. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/elec_prods/subject/mcompres.htm. Accessed August 2008

- 6.International Classification of Diseases, Adapted for Use in the United States, Eighth Revision (ICDA) Washington, DC: World Health Organization; 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Classification of Diseases, or 10th Revision Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 9.James WL, Cossman RE, Cossman JS, Campbell C, Blanchard T. A brief visual primer for the mapping of mortality trend data. Int J Health Geogr 2004;3:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]