Abstract

Objectives. We sought to understand how African American women's beliefs regarding depression and depression care are influenced by racism, violence, and social context.

Methods. We conducted a focus group study using a community-based participatory research approach. Participants were low-income African American women with major depressive disorder and histories of violence victimization.

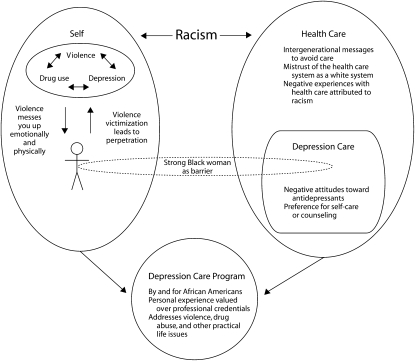

Results. Thirty women participated in 4 focus groups. Although women described a vicious cycle of violence, depression, and substance abuse that affected their health, discussions about health care revolved around their perception of racism, with a deep mistrust of the health care system as a “White” system. The image of the “strong Black woman” was seen as a barrier to both recognizing depression and seeking care. Women wanted a community-based depression program staffed by African Americans that addressed violence and drug use.

Conclusions. Although violence and drug use were central to our participants' understanding of depression, racism was the predominant issue influencing their views on depression care. Providers should develop a greater appreciation of the effects of racism on depression care. Depression care programs should address issues of violence, substance use, and racism.

Although it is unclear whether racial disparities in depressive symptoms can be explained by cultural or socioeconomic factors,1–6 there is ample evidence that important differences exist in depression care. African Americans are significantly less likely than Whites to receive guideline-appropriate depression care.7,8 Several studies have shown that in real-world settings primary care physicians are less likely to detect, treat, refer, or actively manage depression in minority patients than in White patients.9–13 Also, African Americans are less likely than Whites to seek specialty mental health care, accept recommendations to take antidepressants, or view counseling as an acceptable option.8,14–16

Part of understanding a woman's depression is recognizing the social context in which she lives. Violence is a huge problem in our society, and minority and low-income populations bear a disproportionate burden. Studies consistently show that the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) is higher among African American women than among non-Hispanic Whites,17–20 although much of this disparity can be attributed to economic factors.21 There is a strong association between violence victimization and depression.22–31 Despite the important relationship between IPV and mental health, several studies conducted in predominantly non-Hispanic White populations have shown that depressed women with a history of IPV are less likely than other depressed women to seek mental health care.32,33 African American violence survivors may have even greater distrust of the mental health system and encounter more systemic and cultural barriers to receiving care than non-Hispanic Whites.

Our objective in this qualitative study was to understand the experiences and beliefs of depressed African American women residing in Portland, Oregon, a city with relatively low racial diversity, regarding depression and depression care. We focused in particular on understanding how their social context and their experiences of violence influenced their beliefs and choices.

METHODS

We used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach34 throughout the project. We formed an academic–community partnership (the Interconnections Project) consisting of academic researchers, health care providers, domestic violence advocates, IPV survivors, and members and leaders of the Portland Latina and African American communities. All team members served as equal partners throughout the study design, implementation, data analysis, and dissemination phases. The African American and Latino portions of the study were designed together but then were implemented and analyzed separately. Here we focus only on the African American portion of the project.

Recruitment and Eligibility

Community partners distributed flyers about the study at community events, social service agencies, and local establishments. The flyers read: “We are trying to shape a new community-based program to help African American women dealing with issues related to the interconnection of physical health, emotions, relationships, and race.” They did not mention violence or depression so as to not bias the sample. Participants were offered $50.

To be eligible, participants had to be female and at least 18 years of age, had to consider themselves to be African or African American, and had to speak English. Also, they were required to score 15 or higher on the Depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire35 and to answer yes to at least one of 2 items focusing on lifetime experiences of IPV (one of the items addressed being hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise physically hurt by an intimate partner, and the other addressed forced sexual intercourse).

Data Collection

Focus groups were held on separate days, in private community settings, from October 2006 to March 2007. A structured interview guide created collaboratively by the academic and community partners was used in the groups. Initially, women were asked several questions about their experiences and beliefs surrounding health in general, mental health, depression, depression treatments, violence, and drug use, as well as the interrelationship between physical health, mental health, and violence. After being asked to discuss their recommendations for improving depression care, they were presented with some of our ideas for possible depression-based interventions and asked to respond to them. At the end of the session, as a way to increase the validity of our findings, the facilitator summarized what she had heard the women say and asked them to respond. Finally, each woman was asked to state the most important point she wanted to make.

Three African American community members of the research team were trained to facilitate the focus groups. The principal investigator listened to the focus group discussion via a remote headset in a separate room and met with the lay facilitators during breaks. Interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

Both academic and community team members participated in the thematic analysis36 via an inductive approach (consistent with grounded theory). We theorized participants' motivations, experiences, and meanings from what they said rather than making inferences regarding the sociocultural contexts and structural conditions that enabled their individual accounts. The principal investigator and the lay facilitators met regularly to discuss preliminary themes. After all of the focus groups had been completed, team members met to create an exhaustive list of preliminary codes. The principal investigator used Atlas-Ti software (Atlas.ti GmbH, Berlin, Germany) to code all of the transcripts. Three of the authors (V. Timmons, M. J. Thomas, and A. Star Waters), who were also community partners, independently coded the transcripts by identifying quotations they felt were particularly interesting or representative and placing them into a word processing file under headings consisting of the list of preliminary codes.

The group then met again several times. Two of the authors (S. Wahab and A. Mejia, who had not participated in the initial data analysis process) led the group through discussions in which the group compared their findings and refined what they believed were the key messages. The group collaboratively decided on a final framework that collapsed codes into major themes and subthemes. All of the major themes were present in each of the focus groups.

RESULTS

Eighty-three women completed the screening questionnaire, of whom 49 (59%) screened positive for symptoms consistent with major depressive disorder. Only 2 women who otherwise met the inclusion criteria denied physical or sexual abuse. Thirty-four women (72%) participated in 1 of the 5 focus groups. One woman asked to be withdrawn from the study, but we could not separate her data from those of other women in her focus group. Thus, we discuss findings from 30 women in 4 focus groups. A majority (87%) of the women had at some point received treatment for depression, but fewer than half were currently seeing a mental health provider (sample characteristics are presented in Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample: African American Women Residing in Portland, OR, 2006–2007

| Characteristic | Sample, Mean (Range) or % |

| Age, y | 36.2 (19–53) |

| Annual household income, $ | |

| <15 000 | 67 |

| 15 000–24 999 | 20 |

| 25 000–69 999 | 13 |

| ≥70 000 | 0 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 27 |

| High school or equivalent | 46 |

| Some college | 20 |

| College or more | 7 |

| Employment | |

| Working or studying full time | 27 |

| Working or studying part time | 13 |

| Disabled | 17 |

| Unemployed | 43 |

| Insurance coverage | |

| Private | 23 |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 37 |

| No coverage | 40 |

| Depression scorea | 19.16 (15–26) |

| Lifetime physical or sexual IPV victimization | 100 |

| Currently involved with abusive partner | 33 |

| Time, y, since most recent abusive relationshipb | 2.6 (1 mo to 10 y) |

| Currently has primary care provider | 63 |

| Currently has mental health provider | 46 |

| Ever treated for depression | 87 |

| Ever sought domestic violence services | 63 |

| Source through which participant learned about study | |

| Community advisory board member | 24 |

| Another study participant | 24 |

| Other personal contact | 24 |

| Flyer posted at: | |

| Mental health agency | 3 |

| Drug/alcohol treatment center | 7 |

| Health clinic | 7 |

| Domestic violence agency | 3 |

| Other | 3 |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

The Depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire was used to measure depression.

Only women not currently involved with an abusive partner were included.

We identified 12 common themes. We grouped themes according to whether they related to the individual, to the health system, or to preferences for a new depression care intervention. One theme—that the image of the “strong Black woman” acts as a barrier to depression care—related to both the individual and the health system (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Common themes identified in the focus groups: Portland, Oregon, 2006-2007.

Themes Related to the Individual

Violence, drug use, and depression are hard to separate. Women described using drugs or alcohol to self-medicate, but they also recognized how drugs and alcohol exacerbated their problems with depression or violence. According to 1 of the participants:

You or your partner drinking or smoking is going to make it worse, because you guys are both intoxicated and/or high, and that's going to cause friction right there. Or a fight or something. But you're going to keep using when you're in that situation so you can be numb.

Abuse “messes you up.” Participants described complex personal trauma histories filled with multiple forms of violent experiences. They often acknowledged the large, long-lasting impact of violence on their lives, self-images, choices, and behaviors. For example:

I've been raped three times. And then, with my ex-husband, he was very mentally abusive. He tried to smother me with a pillow, he tried to choke me, he tried to throw me out of a moving car…. It affects everything. Everything. I mean, your self-esteem, I mean, the way you hold yourself…. I'd be getting higher, doing whatever just to make sure I could deal with whatever kind of mood he was in. You know, so it affects every part of you. Physical, emotional, and psychological.

Violence victimization leads to perpetration. Many participants spontaneously mentioned concerns about perpetuating violence against their partners, children, or others. One noted:

When I'm depressed, and somebody do something to me, or disrespect me in some kind of way, it's like a glimpse of all the trauma I went through and then it's just like an anger ball and it's just like I got to get it out. I got to. I'll be shaking, and the tears and the hurt and all that and I just got to get out of it because it's like everything that went wrong in my life, everything that scarred me in my life be ready to just react.

Themes Related to the Health Care System

Intergenerational messages to avoid health care. Participants' family members often minimized their health concerns and encouraged them to handle issues on their own. For instance:

When I would tell my mother, you know, she would say, “You're all right. You're going to be all right. Just walk it off,” you know and “It's growing pains,” you know, so the message that gave me was, you know, “Don't go to the doctor.”

Participants discussed conflicts between the beliefs they learned from elders and current medical opinions. In the words of 1 of the women:

I was terrified when I found out that they were going to give me a c-section for my twins. I mean they had to like put me out because I was like “No, don't cut me.” You know. Because old people used to say, “If you get cut and the air hits you, you're going to get cancer. You're going to die.” … And so I think a lot of Black people have grown up hearing that and don't go to the doctor.

Some of the women referenced a history of racism that denied previous generations access to care and continued to inform their current choices. According to 1 participant:

When my grandma gave birth to my dad, she didn't have the option of going to the hospital because the hospital wasn't open to her…. And when my son got sick my granny said “No, you don't need to go spend no money on no Triaminic or whatever it is. I got this right here.”

Mistrust of the health care system as a “White” system. Participants talked about a general mistrust of Whites: “You know, it's in our culture; you don't go tell white people nothing” or “I have met a lot of White people that aren't as honest as Black people.” They perceived the health care system as racially biased, especially in Portland, which has a small population of African Americans.

I mean we didn't wake up in Atlanta, Georgia. We're in Portland, Oregon for God's sake. You know what I'm saying? … My depression might not be like Suzie Ann's depression, OK? Well, they're going to call her name before they call my name. And they're going to treat her just a little bit more different than me.

Negative experiences with health care attributed to racism. The negative experiences described by participants—providers not spending enough time with them, not respecting their intelligence, not providing adequate explanations, and breaking their trust—mirrored the concerns of White participants in an earlier study we conducted among depressed women with a history of IPV.37 The difference with the African American group was that they almost always attributed negative experiences with the health care system to racism. According to 1:

[Health care workers] are just more cold, like emotionally something happened to you that's traumatic, they're very cold. But if somebody that's White come in with the same case, they're “Oh, what's the matter,” taking their time and you know, getting very involved personally with that person, you know, giving them the time that they need. Where I have a question or a concern, or I'm ready to jump off a bridge or something, they could care less.

Themes Related to Depression and Depression Care

When discussing depression, participants described classic symptoms of sadness, anhedonia, hopelessness, social isolation, guilt, loss of energy, and suicidality. We identified 3 additional themes related to their depression care.

Expectation to be a “strong Black woman” acts as a barrier. Many participants talked about strength as a barrier to recognizing depression themselves, accepting it, or being able to seek care for it. Two of the women described the messages they heard growing up:

“Somebody's worser off than we are,” so we just got to deal. So that's where the mask came in. “I'm a strong Black woman,” so I got to be strong and inside you're breaking down.

You know, that was our thing around our house that you're going to be all right like we're Empire State Buildings. You know, while the other people are running around getting help, we're—it's oppressiveness inside.

Another participant echoed how the need to be strong in the face of depression and violence hampered her ability to access care:

I try to be strong but sometimes you just can't. You just break down—it's just—it's a hard thing to want to be strong everyday…. I think African American people, they don't, they don't teach their kids that it's OK to … you know it's OK to go to the doctor's, it's OK to be diagnosed with something, it's OK to go talk to the psychiatrist. It's OK to take medication, because really it is OK.

Negative attitudes toward antidepressants. Most participants had very negative attitudes toward antidepressants. The most common reasons cited were fear of addiction, fear of being “doped up,” and a desire to cope on one's own. According to 1 of the women, “I just refuse to take medication for it because I don't want to be addicted to no medicine. I just deal with it.”

Other common reasons for avoiding antidepressants were lack of information, mistrust of prescribers, and fear of side effects. For example “It's scary nowadays to have the doctors prescribe, because they're so quick to prescribe…. They're in league with the pharmaceutical companies.”

Many participants did describe positive experiences with antidepressants, but almost always in the context of having to take them as a last resort. In the words of 1:

I got really, really depressed and nothing else could do anything else for me and I just, I just started taking the medication … it's working pretty good now.

Preference for self-care and counseling. Participants often wanted to take care of their depression “on their own.” Although some described negative experiences with counseling, participants had more positive attitudes toward counseling than medications. One noted:

I think it works…. Like you said, you don't have to take the meds, you know, you don't have to take the meds—just meet with your counselor once a week for an hour.

Themes Related to Preferences for a Depression Care Intervention

Program staffed by and targeted toward African Americans. Participants expressed a consistent preference for African American staff, with many refusing to participate if counselors were not African American. For instance:

We want to relate to somebody when we talk about our own problems because we hold on to everything so tight. And then we get to talk to somebody of our own race, we open up a little bit more. We might let go a little bit more.

There was also a strong preference for female providers; there was no consensus as to whether a male provider would be acceptable if a female provider were not available. For some, race appeared to be more important than gender in regard to provider choice.

Personal experience valued over professional credentials. There was strong preference for counselors who had personal experience with violence, drug use, poverty, and depression. When asked whether it was important to them that counselors in the program be certified, participants offered such answers as “I'd prefer somebody who's lived the life” and “Don't just get someone that has a medical degree in psychology.” As 1 woman put it, “I'm a firm believer that if you haven't been to Disneyland, you can't tell me too much about it.”

Participants enthusiastically supported the notion of a depression care program facilitated by an African American IPV survivor who would serve as a health advocate. They offered many suggestions as to how such an advocate could potentially help them cope with their depression, offer information, and navigate what they consider a White health care system (e.g., “That means she'll help you with the doctors—or White doctors? Yeah, I think that's great”).

Creative arts–based program that addresses practical life issues. Participants wanted a depression care program that helped them heal through art, crafts, journaling, and self-care activities. They wanted the program to address real-life issues such as domestic violence, substance abuse, housing, employment, and education. They wanted information to be available to family, friends, and others who can support them. They believed that they would benefit from the program only if there was attention to practical needs such as transportation and child care.

DISCUSSION

We explored the beliefs and recommendations of depressed African American women who live in Portland, Oregon, a city with relatively low racial diversity. All of the participants had low incomes and had experienced at least some violence victimization. Within this setting, 2 primary themes quickly and clearly emerged. First, violence, in multiple forms, was present throughout most of our participants' lives and integrally related to their depression. Second, the participants' attitudes about depression care and health care in general were consistently and systematically informed by racism. Participants clearly articulated “cycles” of violence, depression, and drug use that facilitated additional violence in their lives. They were unwavering in their beliefs that experiences of violence were detrimental to both their physical and mental health. However, they rarely invoked experiences of violence when discussing their experiences associated with health care and depression care.

In our earlier study of White women with depressive symptoms and a history of IPV, participants often discussed IPV as a barrier to quality care. For example, participants feared that disclosing a history of violence would lead providers to discount their physical symptoms as imagined, and they believed that experiences of IPV affected their ability to develop trusting relationships with anyone, including providers.37 The African American women taking part in our current study primarily referenced racism, as opposed to violence, while reflecting on their interactions with systems of care. Although violence can be seen as an important component of racism,38 it appeared that participants' overall experience of the health care system as a racist system overshadowed their concerns that a personal history of IPV would create individualized barriers to care. Still, when asked to discuss what they would need from a depression care program, they emphasized the importance of addressing violence, drug use, and other stressors that permeated their lives.

Several authors have documented that African Americans report less satisfaction with health care, have less trust in their providers, and perceive less respect and acceptance from their providers than non-Hispanic Whites.39 Although we were interested in exploring how race informed women's beliefs and choices regarding depression and depression care, it became increasingly clear that racism, rather than race, was the primary issue influencing our participants' beliefs (and experiences), be it via messages to avoid care stemming from the racist experiences of their grandparents or their own experiences of racism in health care interactions.

Previous studies of African American women have revealed longitudinal associations between discrimination and severity of depressive symptoms40; also, greater severity of depression has been related to greater likelihood of a patient reporting that a physician had made an offensive comment and increased dissatisfaction with care.41 Discrimination and racism may have been a particularly important theme in our study because our participants had high levels of depressive symptoms and had experienced very stressful life circumstances.

In their study, Cooper et al. found that African Americans viewed antidepressant medications less favorably than did Whites.42 Our study elaborates on this finding by pointing to our participants' fear of addiction or being “doped up,” their desire to cope on their own, and their mistrust of prescribers' motivations as fueling negative attitudes toward antidepressants.

Our participants felt that pressure to be a “strong Black woman” discouraged them from seeking medical care, and they viewed the acceptance of a mental health diagnosis as the antithesis of the strength discourse. Interestingly, Taylor reported that stereotypical distortions of Black women may also misinform medical care providers and institutions.43 Beauboeuf-Lafontant noted that the notion of the strong Black woman is persistent across the social science literature and concluded her analysis of the literature by warning researchers to “cast a suspicious eye toward the observed use of being strong as a healing mechanism among depressed Black women.”44(p46) Such findings, however, have rarely been incorporated in health care interventions. Our CBPR team used participants' concerns about pressure to be a “strong Black woman” to launch a depression public awareness campaign: “Strong Black Woman: What Are You Burying—Your Feelings or the Myth?”

Limitations

Our study involved several important limitations. Our community-based recruitment process, which relied heavily on word-of-mouth recruitment, resulted in a study population consisting of low-income women who had lived very difficult lives. Our inclusion of minor violence such as slaps in our definition of IPV victimization may have misclassified women as IPV survivors when they had experienced only very minor or rare violence. However, participants' descriptions of violence painted a picture of much more severe, pervasive, repetitive victimization than our screening items would imply. Our results cannot be generalized to all African American depressed women, especially those who live in places with larger African American populations, those with higher incomes, and those who have not experienced IPV.

Implications

Despite these limitations, our study has several important implications. Participants were extraordinarily wary of most depression treatments and providers viewed as associated with White systems of care. Health and mental health service providers and practitioners must endeavor to understand and acknowledge the importance of racism, as well as how it informs the experiences and perceptions of those who have suffered as a consequence of racism. The recognition that depressed African American patients may be interpreting difficulties in the physician–patient relationship as evidence of racism could be a first step in reducing racial bias in clinical care.45 Many authors have suggested concrete ways to help reduce the effects of racism on health care.45,46 Our study also suggests that depression programs should actively address the icon of the “strong Black woman” as a barrier to care.

Our participants were open to treatment and care, providing that medical institutions gain a better cultural understanding and implement advances that would allow for more culturally acceptable interventions. Participants expressed a desire to be treated by African American medical providers or to use African American advocates with “real-life experiences” as a bridge to a White health care system. They emphasized the need for programs that creatively address practical needs related to their complex social situations. Their desires confirm and expand the recommendations of others doing work around depression and African American women. Namely, previous findings suggest the need for culturally specific interventions,15,47 mutual help and support groups,44,47 collaborative models that aim to empower patients,48 and community-based interventions.49,50

Our CBPR team has used the results of the present study to create and pilot a multifaceted, community-based, culturally tailored depression care program. Future research is needed to test the generalizability of our findings, as well as the effectiveness of culturally specific interventions in reducing depression severity and improving depression care among African American women.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant K23MH073008) and the Northwest Health Foundation Kaiser Permanente Community Fund (grant 10571).

We thank Marlen Perez, Anabertha Alvarado, and Richard Loudd for help designing the study; Hilary Galian for providing invaluable research assistance throughout the project, including contributing to protocol development, human participant protection, recruitment, and data analysis; Kerth O'Brien for training community partners to facilitate focus groups; and Bentson McFarland, Martha Gerrity, and MaryAnn Curry for providing mentorship to Christina Nicolaidis. We also thank the participants for sharing their stories and recommendations and the many community members and agencies that provided help with study recruitment and dissemination of results.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University institutional review board. Participants provided written informed consent before taking part in the focus groups.

References

- 1.Skarupski KA, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, et al. Black-white differences in depressive symptoms among older adults over time. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2005;60(3):136–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sachs-Ericsson N, Plant EA, Blazer DG. Racial differences in the frequency of depressive symptoms among community dwelling elders: the role of socioeconomic factors. Aging Ment Health 2005;9(3):201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sen B. Adolescent propensity for depressed mood and help seeking: race and gender differences. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2004;7(3):133–145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bromberger JT, Harlow S, Avis N, Kravitz HM, Cordal A. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of depressive symptoms among middle-aged women: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Am J Public Health 2004;94(8):1378–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gore S, Aseltine RH., Jr Race and ethnic differences in depressed mood following the transition from high school. J Health Soc Behav 2003;44(3):370–389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Hays JC, Simonsick EM, Saunders WB. Symptoms of depression among community-dwelling elderly African-American and white older adults. Psychol Med 1998;28(6):1311–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58(1):55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrington CH. Clinical depression in African American women: diagnoses, treatment, and research. J Clin Psychol 2006;62(7):779–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harman JS, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF., III The effect of patient and visit characteristics on diagnosis of depression in primary care. J Fam Pract 2001;50(12):1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skaer TL, Sclar DA, Robison LM, Galin RS. Trends in the rate of depressive illness and use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy by ethnicity/race: an assessment of office-based visits in the United States, 1992–1997. Clin Ther 2000;22(12):1575–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? J Gen Intern Med 2000;15(6):381–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Ford DE. Patient ethnicity and the identification and active management of depression in late life. Arch Intern Med 2005;165(17):1962–1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leo RJ, Sherry C, Jones AW. Referral patterns and recognition of depression among African-American and Caucasian patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1998;20(3):175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miranda J, Cooper LA. Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19(2):120–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care 2003;41(4):479–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson AP. The use of psychiatric medications to treat depressive disorders in African American women. J Clin Psychol 2006;62(7):793–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rennison M, Welchans S. Intimate Partner Violence: Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Alcohol-related problems, drug use, and male intimate partner violence severity among US couples. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2002;26(4):493–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorenson SB, Upchurch DM, Shen H. Violence and injury in marital arguments: risk patterns and gender differences. Am J Public Health 1996;86(1):35–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rennison C, Planty M. Nonlethal intimate partner violence: examining race, gender, and income patterns. Violence Vict 2003;18(4):433–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marais A, de Villiers PJ, Moller AT, Stein DJ. Domestic violence in patients visiting general practitioners—prevalence, phenomenology, and association with psychopathology. S Afr Med J 1999;89(6):635–640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts GL, Lawrence JM, Williams GM, Raphael B. The impact of domestic violence on women's mental health. Aust N Z J Public Health 1998;22(7):796–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen R, Gazmararian J, Andersen Clark K. Partner violence: implications for health and community settings. Womens Health Issues 2001;11(2):116–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. J Fam Violence 1999;14(2):99–132 [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Derogatis LR, Bass EB. Relation of low-severity violence to women's health. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13(10):687–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse: unhealed wounds. JAMA 1997;277(17):1362–1368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. The “battering syndrome”: prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med 1995;123(10):737–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicolaidis C, Curry M, McFarland B, Gerrity M. Violence, mental health, and physical symptoms in an academic internal medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19(8):819–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houry D, Kemball R, Rhodes KV, Kaslow NJ. Intimate partner violence and mental health symptoms in African American female ED patients. Am J Emerg Med 2006;24(4):444–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuigan WM, Middlemiss W. Sexual abuse in childhood and interpersonal violence in adulthood: a cumulative impact on depressive symptoms in women. J Interpers Violence 2005;20(10):1271–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scholle SH, Rost KM, Golding JM. Physical abuse among depressed women. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13(9):607–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicolaidis C, McFarland B, Curry M, Gerrity M. Differences in physical and mental health symptoms and mental health utilization associated with intimate-partner violence versus childhood abuse. Psychosomatics 2009;50(4):340–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA 2007;297(4):407–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicolaidis C, Gregg J, Galian H, McFarland B, Curry M, Gerrity M. “You always end up feeling like you're some hypochondriac”: intimate partner violence survivors' experiences addressing depression and pain. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(8):1157–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young IM. Five faces of oppression. : Wartenberg TE, Rethinking Power Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1992:183–194 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armstrong K, McMurphy S, Dean L, et al. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(6):827–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, Israel BA, Mentz G, Rowe Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: results from a longitudinal analysis. Am J Public Health 2006;96(7):1265–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scarinci IC, Beech BM, Watson JM. Physician-patient interaction and depression among African-American women: a national study. Ethn Dis 2004;14(4):567–573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper LA, Brown C, Vu HT, Ford DE, Powe NR. How important is intrinsic spirituality in depression care? A comparison of white and African-American primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):634–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor JYA. Colonizing images and diagnostic labels: oppressive mechanisms for African American women's health. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1999;21(3):32–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beauboeuf-Lafontant T. You have to show strength: an exploration of gender, race, and depression. Gend Soc 2007;21(1):28–51 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burgess D, van Ryn M, Dovidio J, Saha S. Reducing racial bias among health care providers: lessons from social-cognitive psychology. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(6):882–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Washington DL, Bowles J, Saha S, et al. Transforming clinical practice to eliminate racial-ethnic disparities in healthcare. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(5):685–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bell CC, Mattis J. The importance of cultural competence in ministering to African American victims of domestic violence. Violence Against Women 2000;6(5):515–532 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000;283(2):212–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bent-Goodley TB. Health disparities and violence against women: why and how cultural and societal influences matter. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007;8(2):90–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freedman TG. “Why don't they come to Pike Street and ask us”?: Black American women's health concerns. Soc Sci Med 1998;47(7):941–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]