Abstract

In this cross-sectional, clinic-based study, we estimated 1-year prevalence of intimate partner violence among 986 patients who had elective abortions. We assessed physical, sexual, and battering intimate partner violence via self-administered, computer-based questionnaires. Overall, physical and sexual intimate partner violence prevalence was 9.9% and 2.5%, respectively; 8.4% of those in a current relationship reported battering. Former partners perpetrated more physical and sexual assaults than did current partners. Violence severity increased with frequency. Abortion patients experience high intimate partner violence rates, indicating the need for targeted screening and community-based referral.

Intimate partner violence has far-reaching, adverse consequences for women, children, and families.1–5 In live birth populations, women with unintended pregnancies reported higher intimate partner violence rates than did those with planned conceptions.6–9 Women seeking abortion may be an important target population for intervention because a small but growing body of research suggests that intimate partner violence prevalence is higher among abortion patients than among women who continue their pregnancies.10–15 Most studies, however, have been limited by small sample sizes and failure to measure nonphysical abuse.

METHODS

We conducted this cross-sectional study from November 1, 2007, through July 18, 2008, within a large family planning clinic that provides aspiration and medication abortion. Eligibility criteria included attendance for elective abortion, age 18 years or older, Iowa residency, and English or Spanish proficiency. Following clinic intake, education staff introduced the study to eligible patients in a private room. Participants who provided informed, voluntary consent completed a 10-minute anonymous, self-administered, computer-based questionnaire (English or Spanish) to estimate the 12-month prevalence of physical, sexual, and battering abuse.16 This study was approved by University of Iowa's institutional review board.

Physical and sexual abuse were measured with a modified abuse assessment screening tool.17 Frequency of physical abuse and self-appraisal of injury severity were ascertained. Battering (chronic nonphysical abuse characterized by controlling behaviors and abuse of power) was measured with the Women's Experience With Battering Scale.18,19

The response rate was calculated as the number of women who completed the questionnaire divided by the total eligible; the cooperation rate was calculated as the number of women who completed the questionnaire divided by the eligible women invited to participate.20 We used the Wilcoxon rank sum test to examine associations between the frequency of physical abuse and injury severity for trend across ordered groups.21,22

RESULTS

Of the 1415 abortion clients seen in the clinic, 1193 were eligible, 1108 were invited to participate, 990 consented, and 986 completed the questionnaire. Participation and cooperation rates were high: 82.6% (986 of 1193) and 89.0% (986 of 1108), respectively.

Analysis of the clinic's administrative database confirmed that participants and eligible patients had similar sociodemographic characteristics. The average participant was 25.7 years old. Most were White (10.6% were Black; 8.4% were Latina); were well-educated (some college or more: 66.9%); were employed (72.0%); and had public or private health insurance (64.7%).

One-year prevalence rates of physical and sexual abuse were analyzed by relationship status (Table 1). Among all participants, 11.5% reported being physically hurt by anyone in the past year; 10.0% identified a current or former partner as the perpetrator. The prevalence of sexual abuse by anyone was 4.7% compared with 2.5% for sexual intimate partner violence. Of the 96 women who reported intimate partner violence, 71 (74%) identified a former partner as the perpetrator, whereas 26 (27%) identified the current partner as the perpetrator. The combined prevalence of any physical or sexual abuse was 13.8% versus 10.8% for physical or sexual intimate partner violence.

TABLE 1.

Number and Prevalence Rate per 100 (PR) of Any Physical or Sexual Abuse and Intimate Partner Violence, by Partner Status and Perpetrator: Participants Seeking Induced Abortion at a Women's Health Clinic, November 2007–July 2008a

| Partner Status of Participants and IPV Perpetratorsab | Any Physical Abuse, No. or No. (PR) | Any Sexual Abuse, No. or No. (PR) | Physical or Sexual Abuse, No. or No. (PR) |

| All women | 972 | 972 | 979 |

| Any perpetrator | 112 (11.5) | 46 (4.7) | 135 (13.8) |

| Current partner | 26 (2.7) | 5 (0.5) | 27 (2.8) |

| Former partner | 71 (7.3) | 20 (2.1) | 81 (8.3) |

| Other family member | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.4) |

| Person known to you | 7 (0.7) | 11 (1.1) | 17 (1.7) |

| Stranger | 8 (0.8) | 10 (1.0) | 15 (1.5) |

| Other | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.5) | 7 (0.7) |

| Intimate partner violencec | 96 (9.9) | 24 (2.5) | 106 (10.8) |

| Women with a current partner | 704 | 709 | 711 |

| Any perpetrator | 72 (10.2) | 27 (3.8) | 85 (12.0) |

| Current partner | 26 (3.7) | 5 (0.7) | 27 (3.8) |

| Former partner | 36 (5.1) | 7 (1.0) | 41 (5.8) |

| Other family member | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Person known to you | 5 (0.7) | 10 (1.4) | 14 (2.0) |

| Stranger | 5 (0.7) | 8 (1.1) | 10 (1.4) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) |

| Intimate partner violencec | 61 (8.7) | 11 (1.6) | 66 (9.3) |

| Women with no current partner | 251 | 245 | 250 |

| Any perpetrator | 40 (15.9) | 19 (7.8) | 50 (20.0) |

| Former partner | 35 (13.9) | 13 (5.3) | 40 (16.0) |

| Other family member | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) |

| Person known to you | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.2) |

| Stranger | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.2) | 4 (1.6) |

| Intimate partner violencec | 35 (13.9) | 13 (5.3) | 40 (16.0) |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence. Participants with missing data for physical abuse or sexual abuse were excluded.

Partner status could not be determined for 19 women.

Some participants reported multiple perpetrators.

By current or former partner.

The minority of respondents (26%) not in an intimate relationship at the time of recruitment reported the highest prevalence of physical or sexual intimate partner violence (16.0%) and any physical or sexual abuse (20.0%).

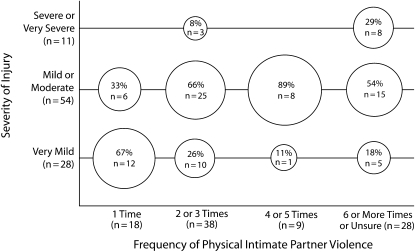

Severity of physical abuse increased incrementally and significantly with the frequency of reported incidents in the past 12 months (Figure 1). Nearly a third of physically abused women reported 6 or more assaults or were unsure of the number (28 of 93). Of the participants who reported on the severity of physical abuse, 58% (n = 54) reported the abuse as mild or moderate, and 12% (n = 11) reported the abuse as severe or very severe.

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of physical abuse by an intimate partner in past 12 months and self-reported injury severity among participants seeking induced abortion at a women's health clinic: November 2007–July 2008.

Note. Nonparametric test for trend across ordered groups: z = 3.35; P < .001.

Battering was assessed among women with a current partner (with exclusive reference to that partner): 8.4% (n = 60) screened positive on the Women's Experience With Battering Scale. Of these, 58.3% (n = 35) reported battering alone, with no other types of intimate partner violence; 23.3% (n = 14) also reported physical intimate partner violence; 6.7% (n = 4) reported all 3 types of intimate partner violence; and 11.7% (n = 7) skipped questions about physical or sexual abuse.

DISCUSSION

Abortion patients had high 12-month prevalence rates of physical and sexual intimate partner violence and abuse by anyone. Former partners perpetrated more assaults than did current partners, suggesting that many women had dissolved their intimate relationship with the abusive partner by the time of enrollment—an observation consistent with findings from a South Carolina study of family practice patients.23

Our estimated prevalence of physical intimate partner violence was consistent with rates from similar clinic populations15 but considerably higher than the nationally estimated prevalence of 3.7% among US women who continue their pregnancies.24 These data suggest that women in violent relationships are more likely to seek abortion services.

Few studies have examined the frequency and severity of physical violence.25 We found that injury severity increased with reported frequency of assaults rather than a pattern of infrequent but very severe abusive events. To our knowledge, ours was the first US study to comprehensively evaluate battering among abortion clients, with 8.4% reporting battering by their current partner.

Methodological strengths included a high participation rate and sample size; use of validated intimate partner violence instruments to screen for 3 intimate partner violence subtypes; and anonymous, computer-based questionnaires to encourage honest reporting.26,27 We did not assess battering by former partners, bidirectional abuse, duration of abuse, or reasons for abortion.

In summary, abortion patients experienced high rates of intimate partner violence, indicating the need for intimate partner violence screening followed by community-based referrals and interventions.

Acknowledgments

The funding sources for this research were the University of Iowa Social Research Center, the University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center (CDC R49 CCR703640), and the National Institutes of Health (R21 HD053850).

The authors acknowledge Hind Beydoun for contributions to the survey instrument, Fiona Tubmen-Scovack for facilitating data collection, and Sherry Sperlich for supporting the field operations.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the University of Iowa's institutional review board.

References

- 1.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 2002;359(9314):1331–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coker AL, Smith PH, Fadden MK. Intimate partner violence and disabilities among women attending family practice clinics. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14:829–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plichta SB. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: policy and practice implications. J Interpers Violence 2004;19:1296–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics 2004;113:320–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peek-Asa C, Maxwell L, Stromquist A, Whitten P, Limbos MA, Merchant J. Does parental physical violence reduce children's standardized test score performance? Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:847–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro R, Peek-Asa C, Garcia L, Ruiz A, Kraus JF. Risks for abuse against pregnant Hispanic women: Morelos, Mexico and Los Angeles County, California. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro R, Peek-Asa C, Ruiz A. Violence against women in Mexico: a study of abuse before and during pregnancy. Am J Public Health 2003;93:1110–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cripe SM, Sanchez SE, Perales MT, Lam N, Garcia P, Williams MA. Association of intimate partner physical and sexual violence with unintended pregnancy among pregnant women in Peru. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008;100:104–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pallitto CC, Campbell JC, O'Campo P. Is intimate partner violence associated with unintended pregnancy? A review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 2005;6:217–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taft AJ, Watson LF. Termination of pregnancy: associations with partner violence and other factors in a national cohort of young Australian women. Aust N Z J Public Health 2007;31:135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourassa D, Berube J. The prevalence of intimate partner violence among women and teenagers seeking abortion compared with those continuing pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2007;29:415–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evins G, Chescheir N. Prevalence of domestic violence among women seeking abortion services. Womens Health Issues 1996;6:204–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glander SS, Moore ML, Michielutte R, Parsons LH. The prevalence of domestic violence among women seeking abortion. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91:1002–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lumsden GM. Partner abuse prevalence and abortion. Can J Womens Health Care Phys Addressing Womens Health Issues 1997;8(1):[13] p [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo J, Fine P, Goetzl L. Abortion disclosure and the association with domestic violence. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:1329–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WebSurveyor Herndon, VA: WebSurveyor Corp; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy: severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA 1992;267:3176–3178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith PH, Earp JA, DeVellis R. Measuring battering: development of the Women's Experience With Battering (WEB) Scale. Womens Health 1995;1:273–288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MJ. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: physical, sexual, and psychological battering. Am J Public Health 2000;90:553–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slattery ML, Edwards SL, Caan BJ, Kerber RA, Potter JD. Response rates among control subjects in case-control studies. Ann Epidemiol 1995;5:245–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilcoxon F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometrics 1945;1:80–83 [Google Scholar]

- 22.StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: Release 10 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coker AL, Derrick C, Lumpkin JL, Aldrich TE, Oldendick R. Help-seeking for intimate partner violence and forced sex in South Carolina. Am J Prev Med 2000;19:316–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Reed E, Raj A. Intimate partner violence victimization prior to and during pregnancy among women residing in 26 U.S. states: associations with maternal and child health. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:140–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, Saltzman LS. Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. Am J Public Health 2007;97:941–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, et al. Approaches to screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: a randomized trial. JAMA 2006;296:530–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mears M, Coonrod DV, Bay RC, Mills TE, Watkins MC. Routine history as compared to audio computer-assisted self-interview for prenatal care history taking. J Reprod Med 2005;50:701–706 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]