Abstract

Objectives. The Internet offers Web sites that describe, endorse, and support eating disorders. We examined the features of pro–eating disorder Web sites and the messages to which users may be exposed.

Methods. We conducted a systematic content analysis of 180 active Web sites, noting site logistics, site accessories, “thinspiration” material (images and prose intended to inspire weight loss), tips and tricks, recovery, themes, and perceived harm.

Results. Practically all (91%) of the Web sites were open to the public, and most (79%) had interactive features. A large majority (84%) offered pro-anorexia content, and 64% provided pro-bulimia content. Few sites focused on eating disorders as a lifestyle choice. Thinspiration material appeared on 85% of the sites, and 83% provided overt suggestions on how to engage in eating-disordered behaviors. Thirty-eight percent of the sites included recovery-oriented information or links. Common themes were success, control, perfection, and solidarity.

Conclusions. Pro–eating disorder Web sites present graphic material to encourage, support, and motivate site users to continue their efforts with anorexia and bulimia. Continued monitoring will offer a valuable foundation to build a better understanding of the effects of these sites on their users.

While health professionals investigate causes of and prevention strategies and treatments for eating disorders and their poor health consequences,1 pro–eating disorder Web sites and communities have emerged wherein users can find material to support the progression and maintenance of eating disorders.2–4 Similar to Web sites that promote other equally unhealthy behaviors such as self-injury and suicide,5 pro–eating disorder Web sites (also identified as pro-Ana and pro-Mia Web sites) are of great concern. A pro–eating disorder Web site is a collection of Internet pages, all accessed through a domain name or IP address, that deliver content about eating disorder such as anorexia and bulimia. This content can be conveyed through text, images, audio, or video, and it encourages knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors to achieve terribly low body weights.

A distinction must be made; unlike Web sites that encourage healthy weights, moderate exercise, and recognized nutrition and diets, many pro–eating disorder sites recommend that their users try intense practices, such as vomiting and fasting, with an emphasis on achieving extremely thin or skeletal appearances. Adolescents exposed to pro–eating disorder Web sites have been shown to have higher levels of body dissatisfaction than adolescents not exposed to these sites, as well as decreased quality of life and longer durations of eating disorders.4,6,7 In addition, increased use of pro–eating disorder sites has been positively correlated with disordered eating behaviors and negatively correlated with disease-specific quality of life among adults (R. Peebles et al., unpublished data, 2010).

Behavior change and communication theories justify concern about pro–eating disorder Web sites. Bandura's social cognitive theory proposes that modeled behaviors are more likely to be imitated when message receivers can relate to the model and perceive rewards with the communicated behavior.8 Vulnerable users may adopt conveyed behaviors not only when they admire online peers but also if they are repeatedly exposed to images of successful models, celebrities, and even real people with life-threatening and dangerously low body weights.

Cultivation theory, a theory developed by communication scholar George Gerbner,9,10 posits that when messages are pervasive and repeated, individuals with higher exposure levels are more likely to accept the conveyed messages as normative. Therefore, frequent visitors to pro–eating disorder Web sites may perceive extreme dieting and exercise as normal rather than symptomatic of a dangerous disease. Given the potential deleterious influence of pro–eating disorder sites, researchers must monitor these online sources to better understand the available messages and resources. The content analysis methodology allows such a systematic review.11,12

We conducted an in-depth examination of pro–eating disorder websites and the messages to which users may be exposed. To date, only a handful of studies have explored pro–eating disorder sites,13–21 and these content analyses have considered fewer than a dozen sites.3,22 These studies seem inadequate in that each reviewed only 12 Web sites and none of the assessments involved more than 1 coder. By contrast, we used extensive first- and second-generation sampling, a well-developed and detailed coding manual (created by the research team), and interrater reliability techniques. As a result, we are able to present a more valid depiction of what visitors to pro–eating disorder Web sites may encounter in this digital space.

METHODS

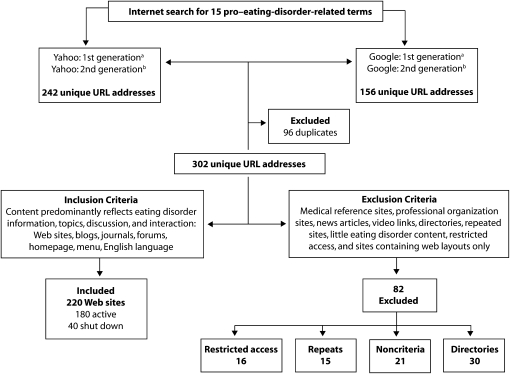

To obtain a valid and generalizable sample for this content analysis, we initially established a population of sites using the Yahoo and Google search engines (Figure 1). We included the following terms in our search: Proana, Pro-Ana, Proanorexia, Pro-Anorexia, Promia, Pro-Mia, Probulimia, Pro-Bulimia, ProED, Pro-ED, Pro eating disorder, Pro-Eating disorder, thin and support, thin and Pro Acceptance, and thin and Pro-Reality. This search (as well as all data collection) occurred in spring 2007.

FIGURE 1.

Establishment of the study population of pro–eating disorder Web sites: 2007.

aLinks from the first 10 pages of results that fit criteria.

bLinks found on the first generation Web pages.

The first 10 pages of search results for each term from each search engine were used to generate a list of Web sites (“first” generation). Next, viable links offered on these sites were included in the sample (“second” generation). This provided a total of 302 unique URL addresses. All Web sites, forums, journals, and blogs characterized by a primary focus on or promotion of eating disorders were included. A primary focus was determined by the core concepts or topics dominating a site's displayed information, discussion, and features. Web sites that included pro-Ana or pro-Mia as one of several topics (i.e., drug use, self-injury, extreme behaviors) were not considered. Furthermore, news articles, medical reference pages, medical journals, and professional or medical organization sites focusing on eating disorders were excluded. A total of 180 active Web sites met the criteria for our analysis.

Before coding the sample, a team of 6 public health and adolescent health researchers reviewed the existing literature and proposed variables for our analysis. Variables were pilot tested on a random sample of 25 Web sites. This testing was conducted in order to streamline the number of variables considered; the team removed approximately a dozen variables from consideration because they were not providing new information. Also, pilot testing resulted in a codebook with detailed guidelines and examples to ensure high reliability.

Two members performed the majority of the coding; however, the entire team was called on to unanimously resolve discrepancies and ambiguous situations. As a means of standardizing techniques across Web sites with varying amounts of content, no more than 10 minutes were spent searching for each variable on any site. For each site, researchers coded 64 variables that fell into 6 general categories, as described in Table 1. Most variables were objective and easy to code; however, the constructs for themes and harm were more subjective.

TABLE 1.

Descriptions of and Details on Coded Variables

| Variable | Description | Details |

| Site logistics | General items that provide logistical information about a site | Site type and purpose, warnings and disclaimers, tones and statements against “wannabes,” and information about the site maintainer |

| Site accessories | Items and tools commonly found on the sites | ED information, letters or creeds to Ana, creative expression sections, and calculators or logs to track caloric intake and body composition |

| Thinspiration, tips, and techniques | Items that can be used by viewers as inspiration or suggestions to motivate or engage in behaviors associated with EDs | Quotes, advice, and images; also, information on how to diet, hide behaviors, fast, purge, exercise, select food and diet pills, and modify personal appearances |

| Recovery | Items providing information on or support with obtaining help to discontinue unhealthy behaviors associated with EDs | Information, tools, or links to recovery treatment sites |

| Perceived themes | Ideas that commonly emerge in discussions of EDs (derived from Norris et al.3) | Control, success, perfection, isolation, sacrifice, transformation, coping, deceit, solidarity, revolution |

| Perceived harm | Subjective assessment of how potentially harmful the site might be; independent and trained researchers assigned a general score | Range from 1 to 5 (1 = not too harmful, may have recovery information; 2 = slightly harmful; 3 = average, typical level of harm; 4 = dangerous; 5 = very dangerous, could do immediate harm) |

Note. ED = eating disorder.

We assessed interrater reliability by double coding the full set of variables from 20 randomly selected Web sites. Although other reliability statistics can be employed, we used percentage agreement because it is unambiguous; coders either agreed or disagreed. The calculated average percentage agreement was 81%, as determined by examining agreement across different Web site variables, some of which had moderate agreement and others of which had near perfect agreement (range: 62%–96%). Discrepancies were examined by a third reviewer, and results were the majority opinion.

The majority of the Web sites examined were available in the public domain. No deception was involved in entering password-protected or invitation-only portions. Exclusive entry to certain pages, requiring approval from a maintainer, occurred with only 9% (n = 27) of the sites; in these cases we requested a password, but if one was not given we collected data from only the publicly available portions.

Our analysis was straightforward and primarily descriptive. Univariate and bivariate relationships were noted; significance was set at the P < .05 level. We used SPSS for Windows 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) in conducting the analyses.

RESULTS

In the sections to follow, we present information on the various features of the sites reviewed. Also, we describe perceived harm findings.

Site Logistics

Most Web sites (79%) were interactive and not static or read only; that is, they allowed a community wherein users could post comments or artwork, communicate via an online forum or message board, or use personalized diet or exercise-related tools. Practically all of the sites (87%) held “free” Web addresses and were hosted through another site; 13% had purchased URLs. It was unclear as to when 24% of the sites had been updated; 29% had been updated in the previous month, and 46% had not been updated in the 30 days before the coding. Approximately half (49%) of the sites were mostly graphic and written at less than an 8th-grade reading level.

Of the sites visited, 84% had pro-Ana content and 63% had pro-Mia content; only 7% included neither type of content in an overt manner. In addition, 31% (n = 56) had a substantial amount of pro-recovery content. Two thirds (67%; n = 120) expressed a combination of these philosophies. In fact, seldom did sites endorse only one focus: only 17% (n = 31) were exclusively pro-Ana, 2% (n = 3) exclusively pro-Mia, and 4% (n = 7) exclusively pro-recovery. Nearly half (n = 86) went on to expressly state a claim of pro–eating disorder or not pro–eating disorder status; of those making a claim, 29% (n = 25) indicated that they were not pro–eating disorder. Of the 60 sites that discussed eating disorders as a lifestyle choice or disease, 58% referred to it as a disease and 42% referred to it as a lifestyle choice.

Approximately 40% (n = 73) of the sites warned users that some of the posted material might be dangerous or distressing; 27% (n = 48) even offered a formal disclaimer that exposure to the site's material might trigger dangerous behaviors and that the site was not responsible for any such ensuing behaviors. It is unclear whether these warnings or claims were posted because of altruistic or litigious reasons. Forty-two percent (n = 26) of the sites that warned users about distressing material also had disclaimers about not being responsible for the site's effects, as compared with only 9% (n = 10) of those without warnings (χ2 = 24.5; P < .001).

Approximately one third (32%; n = 57) of the sites had an overt tone or statement directed to “wannabes.” These were elitist and exclusive statements, varying from polite to harsh, made by those with eating disorders to site visitors who might be trying to develop an eating disorder. An example of a polite statement was “If you are looking to become anorexic or become bulimic by being here then please leave”; an example of a harsh one was

IF YOU WANT TO LOSE WEIGHT, GO ON A DIET FATTY. ONE IS EITHER ANA/MIA, OR NOT. IT IS A GIFT AND YOU CANNOT DECIDE TO HAVE AN EATING DISORDER. SO IF YOU ARE LOOKING FOR A WAY TO LOSE WEIGHT, S-S-S-SORRY JUNIOR!! MOVE ON, TRY JENNY CRAIG.

Approximately three quarters (72%; n = 129) of the sites appeared to be maintained by an individual and the remaining 27% (n = 48) by a group. Half (n = 91) contained a biography of the maintainer, and nearly all (98%; n = 101) revealed the site administrator's gender as female. Age of the site maintainer was not available for 62% of the sites; of those with age information, 16% stated that they were maintained by adolescents, 66% by young adults (18–24 years), and 18% by older adults (25 years or older). Contact listings for site maintainers were provided on 79% (n = 142) of the sites; 55% (n = 98) provided an e-mail contact, and 31% (n = 56) used an automatic but anonymous system. Only 13% (n = 23) of maintainers offered an overt statement indicating that their own eating disorder was a problem.

Site Accessories

Table 2 provides data on site accessories. Nutritional information and charts on caloric intake and expenditure were regularly included, whereas more interactive features, such as calculators and food and activity diaries, were less common. Familiar measures of calories for foods and minutes for time were used in practically all of the accessories. Most Web sites offered visitors enough information to perform these calculations on their own. Sites with any accessories often had several; 24% (n = 42) had 2 or more accessories.

TABLE 2.

Accessories Found on the Reviewed Web Sites (n = 180): 2007

| Accessory | Present on the Site, % | Links to Another Site, % | Not Present on the Site, % |

| Food calculator | 30 | 8 | 62 |

| Food diary | 16 | 5 | 79 |

| Activity diary | 12 | 2 | 86 |

| Basal metabolic rate calculator | 10 | 7 | 83 |

| Body mass index calculator | 16 | 10 | 74 |

Thirty-eight percent (n = 69) of the Web sites offered detailed information about eating disorders, and 2% (n = 3) contained links to other sites that provided information on eating disorders. This information ranged from basic definitions to more involved descriptions of risk factors, symptoms, effects, and treatments.

Sixteen percent of the sites (n = 29) had a written creed or oath to Ana or a statement of “thin commandments” (the box on the next page provides examples of this content). Nearly half (42%; n = 76) of the sites provided venues for artistic expression, created by either the site maintainers or users. Poetry (such as that presented in the box on the next page) was common, but site users also posted artwork, music, and videos. Claims that eating disorders were a lifestyle choice were not associated with any increase in likelihood of artistic expression on the sites.

Examples of Creeds, “Thin Commandments,” and Poetry in Pro–Eating Disorders Web Sites

Ana Creed

I believe in Control, the only force mighty enough to bring order to the chaos that is my world. I believe that I am the most vile, worthless and useless person ever to have existed on this planet, and that I am totally unworthy of anyone's time and attention. I believe that other people who tell me differently must be idiots. If they could see how I really am, then they would hate me almost as much as I do. I believe in oughts, musts and shoulds as unbreakable laws to determine my daily behavior. I believe in perfection and strive to attain it. I believe in salvation through trying just a bit harder than I did yesterday. I believe in calorie counters as the inspired word of god, and memorize them accordingly. I believe in bathroom scales as an indicator of my daily successes and failures. I believe in hell, because I sometimes think that I'm living in it. I believe in a wholly black and white world, the losing of weight, recrimination for sins, the abnegation of the body and a life ever fasting.

—Author unknown

The Thin Commandments

If you aren't thin you aren't attractive.

Being thin is more important than being healthy.

You must buy clothes, cut your hair, take laxatives, starve yourself, do anything to make yourself look thinner.

Thou shall not eat without feeling guilty.

Thou shall not eat fattening food without punishing oneself afterward.

Thou shall count calories and restrict intake accordingly.

What the scale says is the most important thing.

Losing weight is good/gaining weight is bad.

You can never be too thin.

Being thin and not eating are signs of true will power and success.

—Carolyn Costin, Your Dieting Daughter: Is She Dying for Attention?30

Twisted Minds

some look at us and call us crazy

how little they really know

they pass us by and stare

like we're in some sickly show

don't they see?

it is not us who is at fault

they kill their bodies with fats and grease

but we give our bodies nothing at all

so, you see,

we really are the purest of the pure

nothing but skin and bones,

plus a scale to reassure

so think about which one of us is on top

next time you stop and stare

for we float in the realm of nonexistence

where all we need is air …

—Melissa Cox, with permission

Thinspiration, Tips, and Techniques

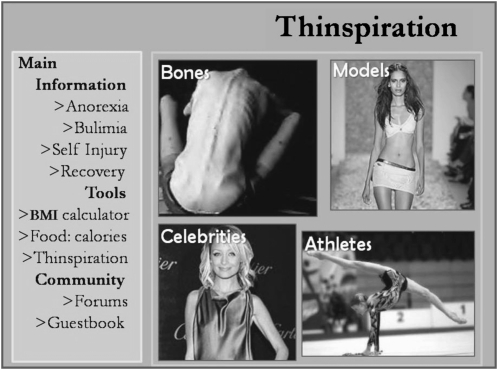

Of the Web sites reviewed, 85% (n = 153) included “thinspiration”: images or prose intended to inspire weight loss. In a majority (58%; n = 88) of cases, these sites contained images overtly labeled as thinspiration; another subset (37%; n = 56) contained similar images that were not identified as thinspiration; and a small group (6%; n = 9) had a section listed as “under construction.” Known fashion models were most frequently shown (66% of sites included at least one photograph of a model), followed by celebrities (57%), real people (44%), and athletes (12%). Figure 2 presents a prototype of a thinspiration Web page.

FIGURE 2.

Example of a “thinspiration” page.

Thinspiration sections often displayed a group (in our analyses, defined as 5 or more) of models (40%; n = 72), celebrities (24%; n = 44), real people (16%; n = 29), or athletes (4%; n = 7). Similarly, sites often included several types of images. For example, sites including photos of thin models were also likely to have images of thin celebrities (χ2 = 34.3; P < .001), thin real people (χ2 = 9.1; P < .005), and thin athletes (χ2 = 4.3; P < .05). Only 18% of the sites had no such pictures, 23% had just 1 type of picture, 28% had 2 types, and 31% had 3 or more types. Other types of thinspiration were also shown: 13% of the sites included “reverse triggers” or images of overweight people, 11% showed photos of food, and 12% incorporated images not falling into any of these categories (such as videos, cartoon images, and music lyrics that could encourage self-harm).

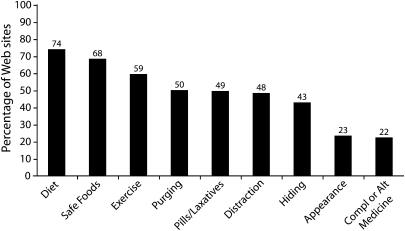

“Tips and techniques” that could foster eating disorder behaviors were another common feature of pro–eating disorder Web sites; 40% had a section overtly labeled as containing tips for practicing eating disorder behaviors, and an additional 43% offered such tips throughout the site without designating a particular area for this purpose. Figure 3 presents common tips. More than 70% of the sites offered dieting strategies, including specific dietary regimes and advice on fasting; 68% listed “safe” foods or charts with low-calorie foods; half offered tips on purging or the use of laxatives or diet pills; and 43% offered advice on how to hide an eating disorder from others.

FIGURE 3.

Percentages of Web sites featuring various tips for engaging in eating-disordered behaviors.

Note. Compl or Alt = complementary or alternative.

Tips ranged from simple and seemingly harmless (“Sit up straight. You'll burn at least ten percent more calories sitting upright than reclining”) to intricate and potentially life threatening (“TO PURGE: You can start off with two fingers or a Toothbrush—3 fingers if nothing is happening. Next, rub the back of your throat; you should feel sort of a Button-ish thing at the back. Well, you need to push it!”). Sites offered a range of diverse tips; only 17% contained no tips or techniques, 5% offered 1 type, 4% listed 2 types, and 74% displayed 3 or more types.

Recovery

A feature of many of the sites was the inclusion of recovery-oriented advice or information. Within our sample of Web sites, 38% contained recovery-oriented information or links to other sites with recovery content, and 21% featured specific sections dedicated to recovery. Thirteen percent of these sites offered an interactive discussion of recovery, and 2% included images that could be considered “anti-thinspiration” (i.e., photos of models who had died from anorexia or celebrities who had recovered and were living happily at a normal weight).

Discussions of media literacy and how photos can be altered so that subjects appear thinner were also included on 13% of the sites. Sites that described eating disorders as a disease showed a trend toward being more likely than sites that described eating disorders as a lifestyle choice to have any recovery-oriented material or links (70% vs 30%; χ2 = 2.5; P = .10).

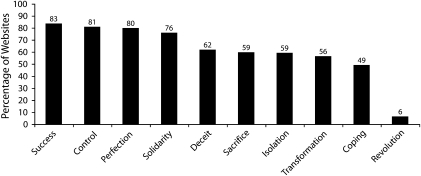

Themes

Using a grounded theory approach, Norris et al. described prominent themes that appear on pro–eating disorder Web sites.3 To monitor and track changes, we considered these same themes; as can be seen in Figure 4, the most common were those of success, control, perfection, and solidarity. An example of control might be found in an Ana creed wherein one feels that committing to an eating disorder will help bring order to the chaos in one's world (see the box on the next page).

FIGURE 4.

Percentages of Web sites featuring various themes relating to eating disorders.

Issues involving isolation, where people describe how they need to be separate from, for example, all of the “obese fatties around that want me to be just like them,” were found on close to 60% of the sites. Revolution, characterized by statements such as “We can choose to live as victims, in that helpless, hopeless victim mentality[, or] we can choose to stand up and fight, take action, take control, make things happen,” was found on only 6% (n = 11) of the sites, and it was strongly associated with recovery-oriented content or links (13% vs 3% of sites without such content; χ2 = 8.1; P < .01).

Practically all (98%) of the sites had at least 2 themes; 3% had 2, 5% had 3, and 90% had 4 or more themes. Most themes were significantly associated with each other in cases in which there was a “co-presence” of multiple themes. The only exceptions were revolution, which was associated only with solidarity (100% of sites with a revolution theme vs 0% of sites without such a theme; χ2 = 3.7; P ≤ .05) and isolation (91% vs 9%; χ2 = 5.0; P < .05), and solidarity, which was strongly associated with deceit (85% of sites with solidarity vs 15% of those without; χ2 = 13.1; P < .001), isolation (70% vs 30%; χ2 = 27.6; P < .001), transformation (62% vs 38%; χ2 = 7.2; P < .001), and coping (56% vs 44%; χ2 = 10.9; P < .001) but not success, control, or perfection.

Perceived Harm

Perceived harm was scored on a scale from 1 (not too harmful, may have recovery information) to 5 (very dangerous, could do immediate harm; Table 1). However, to allow sufficiently large sample sizes for meaningful analyses, we grouped scores into low harm (a score of 1, 28%), medium harm (scores of 2 [27%] or 3 [22%]), and high harm (scores of 4 [18%] or 5 [6%]) categories. Web sites grouped in the lowest level of perceived harm (n = 47) often included some recovery information and aspects that could be considered helpful, with 26% of these sites including a separate section devoted to recovery.

Sites with medium levels of perceived harm (n = 83) had similar content and were categorized by independent and trained reviewers as somewhat dangerous. Sites with high levels of perceived harm (n = 39) were considered dangerous or very dangerous, and the content featured on these sites could lead to immediate and life-threatening problems. Patterns emerged with these groupings, and Table 3 shows how site features were significantly associated with assigned harm ratings.

TABLE 3.

Web Site Features Associated With Perceived Harm Categories (n = 180): 2007

| Perceived Harm Categorya |

|||||

| Feature | Low, % | Medium, % | High, % | χ2 | P |

| Site logistics | |||||

| Declares anorexia a lifestyle choice | 0 | 18 | 26 | 12.5 | <.001 |

| Offers a warning about distressing material | 30 | 42 | 62 | 8.8 | <.05 |

| Host admits EDs are a personal problem | 23 | 13 | 3 | 7.6 | <.05 |

| Letters to Ana, creeds, commandments | 4 | 18 | 28 | 9.1 | <.05 |

| Diatribe against “wannabes” | 26 | 29 | 49 | 6.2 | <.05 |

| Site accessories: food and calorie counts | 17 | 46 | 54 | 14.6 | <.001 |

| Devoted section to thinspiration | 81 | 89 | 90 | NS | NS |

| Models | 51 | 69 | 82 | 9.5 | <.01 |

| Athletes | 4 | 18 | 8 | 6.3 | <.05 |

| Reverse triggers | 4 | 15 | 21 | 5.3 | .07 |

| Devoted section to tips and tricks | 55 | 93 | 100 | 41.0 | <.001 |

| Dieting techniques | 40 | 86 | 95 | 43.3 | <.001 |

| Purging techniques | 19 | 57 | 80 | 32.8 | <.001 |

| Hiding an ED | 11 | 48 | 77 | 38.9 | <.001 |

| Diet pills/laxatives | 19 | 54 | 77 | 29.8 | <.001 |

| “Safe” foods | 36 | 82 | 82 | 33.4 | <.001 |

| Exercise tips | 26 | 72 | 72 | 30.5 | <.001 |

| How to distract oneself from eating | 34 | 49 | 64 | 7.8 | <.001 |

| Recovery information | 32 | 37 | 28 | NS | NS |

| Themes | |||||

| Control | 64 | 81 | 100 | 17.8 | <.001 |

| Success | 64 | 87 | 100 | 21.5 | <.001 |

| Perfection | 72 | 77 | 87 | NS | NS |

| Isolation | 38 | 64 | 72 | 11.7 | <.005 |

| Sacrifice | 34 | 69 | 80 | 22.1 | <.001 |

| Transformation | 47 | 52 | 72 | 6.0 | <.05 |

| Coping | 30 | 52 | 64 | 10.8 | <.005 |

| Deceit | 30 | 70 | 87 | 33.6 | <.001 |

| Solidarity | 70 | 78 | 82 | NS | NS |

| Revolution | 9 | 4 | 5 | NS | NS |

Note. ED = eating disorder; NS = nonsignificant.

Values represent the frequency at which the listed features were found in the respective (low, medium, high) categories.

DISCUSSION

Pro–eating disorder Web sites are an interactive resource with a range of accessories and features available to anyone with an Internet connection. The sites were alarmingly easy to access and understand, with few requiring membership and half written at less than a high school grade level. The sites often served as a venue for expression wherein users could voice opinions or post original poetry or artwork. Striking images of glorified but emaciated models, celebrities, and real people were found throughout. Suggestions on how to lose weight, exercise, and conceal one's behaviors were common. It is clear from our analysis that pro–eating disorder Web sites are available and dynamic communities with ever-changing, user-contributed content.

Although pro–eating disorder sites have been described as portraying eating disorders as a lifestyle choice, fewer than 20% of the examined sites expressed this stance. Frequently the content of these sites was not overtly pro–eating disorder but nonetheless contained the same elements as sites that declared themselves as pro-Ana. The subjective scale developed for this study suggests that the most harmful sites included warnings about distressing material, inform “wannabes” that they should not enter, and include tips and techniques describing multiple and extreme dieting behaviors.

Less subjectively harmful Web sites were far less likely to declare anorexia as a lifestyle choice or to have dieting tips, and they often provided recovery information. In fact, it is somewhat surprising that nearly one third of the sites contained some type of recovery-oriented focus. This situation could reflect a duality of purpose for pro–eating disorder visitors, who may feel pulled simultaneously toward continued eating disorder behaviors and recovery. These stories and images of people who have successfully sought treatment for eating disorders might convince a site visitor that eating disorders are not a way of life; however, it is equally possible that sites containing positive messages of recovery alongside thinspiration and techniques could entice a larger demographic to this online world.

Themes were common, and sites often featured more than one theme. The only theme that stood out as less common than others was that of revolution, which was also associated with recovery-oriented content, isolation, and deceit and was not significantly associated with harm. Themes of solidarity and perfection, although highly prevalent, were also not associated with harm on our subjective scale. These themes may be valuable in future qualitative work examining these sites.

Many Web sites offered information on eating disorders and weight loss techniques; however, these “facts” were displayed in an unmonitored and often distorted way, with no guarantee of accuracy or credibility. Although some of the concepts appear to be the suggestions of site administrators who have attempted a particular activity (i.e., 48 hours of fasting), others seem to be “lifted” from more established diet and physical activity sites. One fascinating example of co-opting and distorting well-intentioned messages exists with the often-featured “thin commandments.” These commandments were developed by a well-respected and experienced eating disorder specialist, through field work with patients, as a tool to help parents better understand their daughters with anorexia. These commandments were often altered and displayed on pro–eating disorder Web sites, without permission and out of their original context, as examples of pro-Ana philosophy.

Social cognitive theory would warn that the high prevalence of interaction opportunities in the pro–eating disorder community has the potential to be extremely harmful if viewers are learning dangerous behaviors from one another, particularly if they are similar in age and gender. Other studies suggest that discussing techniques and perceived benefits may also have contagious effects on those not yet committed to the behaviors.5 The disclaimers included on pro–eating disorder Web sites may warn unsuspecting readers away from distressing content but also may entice vulnerable individuals to read further. Although there is no evidence as to the impact of warnings or disclaimers on pro–eating disorder sites, research on other media such as movies and video games with adult ratings suggests that labels might entice young viewers to want to see media that are not appropriate for them.23

Behavioral and communication theories, such as the social cognitive and cultivation theories mentioned earlier,8,9 would also suggest that the most deleterious components of these sites are the evocative images depicted coupled with constant social support encouraging extreme behaviors. On these Web sites, striving to be underweight is deemed not only as normative but as a signal of success. Only 13% of site maintainers offered an overt statement indicating that their own eating disorder was a problem. In addition, the Internet's easy accessibility allows users to tap into a site's features at any time of day or night.

Social interaction is the most common reason young people use the Internet.24 This may be particularly relevant to the eating disorder online community, as research shows that individuals suffering from eating disorders have difficulty relating with same-age peers, attempt to hide their eating disorder behaviors, and often experience shame and isolation.25–28 Online venues for interaction with friends or strangers may seem like a safer and even appropriate place to disclose personal information. Furthermore, the Internet allows one to not only maintain relative anonymity but also easily retreat from criticism or uncomfortable situations.

Strengths and Limitations

After a 2001 request from several national associations of health professionals, the search engine Yahoo and MSN agreed to shut down Web sites that were overtly pro-anorexia or pro-bulimia.29 This led to the remaining sites concealing their purposes, going underground, and using other servers, proving that Internet content is extremely difficult to regulate. Because we employed a snowball approach to locating pro–eating disorder Web sites, we believe that our sample included more clandestine sites that could elude a basic search engine approach. Still, our approach may not have captured all pro–eating disorder sites.

It should be kept in mind that Web sites are dynamic and sometimes short-lived. Returning to the sampled sites might reveal new data. This analysis represents a snapshot in time of pro–eating disorder Web sites; more regular monitoring is warranted. The constant change inherent in the Internet represents an obvious limitation of our study given that, despite our efforts to be as efficient as possible, multiple sites were already shut down when our study began the coding phase. Thus, our original search provided many links that could not be further examined, and this limited the final sample.

A final limitation concerns the subjectivity involved in an analysis such as ours. We had multiple researchers consider the data objectively, adhering to a strict coding scheme. However, one variable—our harm scale—certainly had a researcher–health professional bias. Although we believe that a quarter of the Web sites examined communicated very harmful messages, site maintainers or users might disagree.

Conclusions

Content analyses such as the one described here provide systematic data on what is available and likely to be seen by users of pro–eating disorder Web sites. In addition, we have provided a methodology to characterize the harmful nature of these sites by noting the features significantly associated with higher levels of perceived harm. Different methodologies must be employed to determine whether and how exposure to such material and media affects users. Coupled with this work, our research team has been investigating the relationship between frequent exposure and use of pro–eating disorder Web sites and the severity of disordered eating behaviors and quality of life impairment (R. Peebles et al., unpublished data, 2010).

Because technology is constantly advancing, these Web sites will evolve and change. Already, recent media reports have noted that pro–eating disorder sites now use more video and social networking approaches,29 and we suspect this interactivity will increase. To better understand how messages and potential harm are communicated through such media venues, researchers must continue to investigate both the messages an individual is exposed to and their impact. Although technological, political, and cultural challenges would be abundant, attempts could be made to regulate pro–eating disorder sites. However, such efforts and actions cannot move forward without important information on existing messages and their effects.

Human Participant Protection

The institutional review boards at both Johns Hopkins University and Stanford University reviewed this research and determined that no protocol approval was necessary.

References

- 1.Stice E, Shaw H. Eating disorder prevention programs: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 2004;130(2):206–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lapinski MK. StarvingforPerfect.com: a theoretically based content analysis of pro-eating disorder Web sites. Health Commun 2006;20(3):243–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris ML, Boydell KM, Pinhas L, Katzman DK. Ana and the Internet: a review of pro-anorexia Websites. Int J Eat Disord 2006;39(6):443–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson JL, Peebles R, Hardy KK, Litt IF. Surfing for thinness: a pilot study of pro-eating disorder Web site usage in adolescents with eating disorders. Pediatrics 2006;118(6):e1635–e1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitlock JL, Powers JL, Eckenrode J. The virtual cutting edge: the Internet and adolescent self-injury. Dev Psychol 2006;42(3):407–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper K, Sperry S, Thompson JK. Viewership of pro-eating disorder Websites: association with body image and eating disturbances. Int J Eat Disord 2008;41(1):92–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardone-Cone AM, Cass KM. What does viewing a pro-anorexia Website do? An experimental examination of Website exposure and moderating effects. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40(6):537–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory. : Vasta R, Annals of Child Development Vol. 6 Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1989:1–60 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heath RL, Bryant J. Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesse-Biber SLP, Quinn CE, Zoino J. The mass marketing of disordered eating and eating disorders: the social psychology of women, thinness and culture. Womens Stud Int Forum 2006;29(2):208–224 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber RP. Basic Content Analysis 2nd ed Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Custers K, Van den Bulck J. Viewership of pro-anorexia Websites in seventh, ninth and eleventh graders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2009;17(3):214–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tierney S. Creating communities in cyberspace: pro-anorexia Web sites and social capital. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2008;15(4):340–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gavin J, Rodham K, Poyer H. The presentation of “pro-anorexia” in online group interactions. Qual Health Res 2008;18(3):325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eichenberg C, Brahler E. “Nothing tastes as good as thin feels…”: considerations about pro-anorexia Websites. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2007;57(7):269–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Csipke E, Horne O. Pro-eating disorder Websites: users’ opinions. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2007;15(3):196–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brotsky SR, Giles D. Inside the “pro-Ana” community: a covert online participant observation. Eat Disord 2007;15(2):93–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tierney S. The dangers and draw of online communication: pro-anorexia Websites and their implications for users, practitioners, and researchers. Eat Disord 2006;14(3):181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulveen R, Hepworth J. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of participation in a pro-anorexia Internet site and its relationship with disordered eating. J Health Psychol 2006;11(2):283–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giles D. Constructing identities in cyberspace: the case of eating disorders. Br J Soc Psychol 2006;45(3):463–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harshbarger JL, Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Mayans L, Mayans D, Hawkins JH. Pro-anorexia Websites: what a clinician should know. Int J Eat Disord 2008;42(4):367–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bushman B. Effects of warning and information labels on attraction to television violence in viewers of different ages. J Appl Soc Psychol 2006;36(9):2073–2078 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borzekowski DL. Adolescents’ use of the Internet: a controversial, coming-of-age resource. Adolesc Med Clin 2006;17(1):205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerner B, Wilson PH. The relationship between friendship factors and adolescent girls’ body image concern, body dissatisfaction, and restrained eating. Int J Eat Disord 2005;37(4):313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schutz HK, Paxton SJ. Friendship quality, body dissatisfaction, dieting and disordered eating in adolescent girls. Br J Clin Psychol 2007;46(1):67–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart MC, Schiavo RS, Herzog DB, Franko DL. Stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination of women with anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2008;16(4):311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vandereycken W, Van Humbeeck I. Denial and concealment of eating disorders: a retrospective survey. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2008;16(2):109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reaves J. Anorexia goes high tech. Time Magazine Available at: http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,169660,00.html. Accessed May 3, 2010

- 30.Costin C. Your Dieting Daughter: Is She Dying for Attention? New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1997 [Google Scholar]