Abstract

Background

Cancer prevention clinical trials seek to enroll individuals at increased risk for cancer. Little is known about attitudes among physicians and at-risk individuals towards cancer prevention clinical trials. We sought to characterize barriers to prevention trial participation among medical oncologists and first-degree relatives of their patients.

Methods

Physician participants were practicing oncologists in Pennsylvania. Eligible first-degree participants were adult relatives of a cancer patient being treated by one of the study physicians. The influence of perceived psychosocial and practical barriers on level of willingness to participate in cancer prevention clinical trials was investigated.

Results

Response rate was low among physicians, 137/478(29%), and modest among eligible first-degree relatives, 82/129(64%). Lack of access to an eligible population for prevention clinical trials was the most commonly cited barrier to prevention clinical trials among oncologists. Nearly half (45%) of first-degree relatives had not heard of cancer prevention clinical trials, but 68% expressed interest in learning more, and 55% expressed willingness to participate. In the proportional odds model, greater information source seeking/responsiveness (i.e. interest in learning more about clinical prevention trials from more information sources)(p=0.04), and having fewer psychosocial barriers (p=0.02) were associated with a greater willingness to participate.

Conclusions

Many individuals who may be at greater risk for developing cancer because of having a first-degree relative with cancer are unaware of the availability of clinical cancer prevention trials. Nonetheless, many perceive low personal risk associated with these studies, and are interested in learning more.

Keywords: Cancer, prevention, clinical trials, barriers

Introduction

Cancer prevention clinical trials seek to enroll individuals at increased risk for cancer, whether due to a strong personal or family history of pre-malignancy or cancer. While cancer clinical trials commonly provide experimental therapies to acutely ill individuals, prevention trials offer “healthy” participants novel screening, surgical, and/or medical interventions in an attempt to reduce future cancer risk by affecting pre-symptomatic intermediate endpoints (e.g., reducing breast density or colorectal adenoma burden) at the cost of possible quality-of-life reductions due to invasiveness of screening, the need to take medication, and time demands. Thus, accrual to prevention clinical trials may be even more difficult than accrual to traditional treatment studies, particularly given that recruitment necessarily targets a population of asymptomatic, healthy individuals facing an uncertain risk of cancer. For a prevention trial to be successful, special attention to the barriers facing at-risk populations may be necessary to improve acceptance and participation.

In general, psychosocial and practical barriers to treatment clinical trial participation are well documented (1-12). However, little is known about the influences on participation in prevention clinical trials. In an effort to conceptualize potential barriers to participation, we applied the Cognitive-Social Health Information Processing (C-SHIP) model, which provides a framework for considering how individuals at increased health risk cognitively and affectively approach the opportunity of cancer prevention, including the health-related expectations, values, and goals that influence their decision making processes (13).

Little is known about attitudes among physicians and at-risk individuals towards cancer prevention clinical trials. As an initial step, we sought to characterize barriers to prevention trial participation, as perceived by medical oncologists and the first-degree relatives (FDRs) of their patients. FDRs of cancer patients frequently represent a higher-than-average risk population for cancer because of shared genetic, behavioral, and environmental exposures. For this reason, they may serve as a highly relevant participant pool in cancer prevention research. For this study, we measured awareness of, level of interest in, and willingness to participate in clinical prevention trials. We further examined the practical and perceived barriers that may distinguish potentially at-risk individuals who have variable levels of willingness to participate in a cancer prevention clinical trial.

Methods

Recruitment and Procedures

This manuscript reports data obtained from a study exploring barriers to treatment and prevention clinical trials. Results regarding treatment clinical trials barriers have been previously published, as have the methods used identify oncologists and patients sampled (12). Briefly, eligible physician participants were practicing medical oncologists in Pennsylvania. Eligible patients were under the ongoing care of a medical oncologist, and had a diversity of cancer diagnoses including: breast cancer (22%), lung cancer (16%), leukemia (12%), colorectal cancer (10%), prostate cancer (8%), and lymphoma (7%). Patients were either in active treatment or follow-up. Eligible FDRs were first-degree relatives (>18 years) of a patient being followed by one of the physician participants. All participants could communicate in English. Medical oncologists (n=478) were identified through membership lists of the American Board of Internal Medicine and American Society of Clinical Oncology (12), representing all practicing oncologists in Pennsylvania. Each oncologist was mailed 1 physician survey and 10 patient surveys to distribute to patients. Participants received $50. Oncologists who did not return surveys within 4 weeks of the initial mailing were called or emailed with a reminder to complete the questionnaire. Patient participants were provided a postage-paid return envelope for their completed survey, and received $25. For the companion study described here, patient participants were asked at the time of study enrollment to provide names and contact information of FDRs who may be interested in completing a similar survey. Surveys from FDRs were in general completed and returned within 1 month of index patient/participant enrollment. Individuals identified by patient participants were mailed a survey with a postage-paid return envelope. FDR participants were provided with a $25 reimbursement for survey completion. FDRs were linked to the treated patient via an identification number. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the coordinating center (FCCC).

Measures

To inform and guide the development of oncologist and FDR surveys, we conducted 6 focus groups. A focus group guide was developed based on our objectives to understand the barriers to clinical prevention trial participation. The focus groups were facilitated by a clinical psychologist (JB). Two groups (1 oncologist/1 FDR) were conducted at each of 3 sites representing an National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center, an urban medical center with a medically underserved, ethnically diverse population, and a hospital-based suburban community practice (i.e., Fox Chase Cancer Center, Temple University Cancer Center, Delaware County Memorial Hospital) to identify relevant practical and psychosocial barriers to prevention trial participation. The proceedings were audio-taped and transcribed. Two members of the research team reviewed the transcripts for themes relating to barriers to prevention trial participation. The themes were compared, summarized, and discussed among the entire research team. The oncologist and FDR questionnaires developed were guided by the Cognitive-Social Health Information Processing (C-SHIP) framework (13), as well as the available literature, and focus group feedback. The C-SHIP model identifies five dynamic components to the adoption of health behaviors, such as clinical trial participation. These components include: 1)knowledge and awareness of clinical trials along with perceived vulnerability and susceptibility to cancer; 2)beliefs and expectancies, for example, self-efficacy or confidence in one's ability to manage the affect associated with clinical trials, or the belief that clinical trials are only used as a last resort when other therapies do not work; 3)cancer related affect, for example, worry about one's risk for cancer, 4)values and goals with respect to one's health, and 5) self-regulation and ability to develop and manage action plans around one's treatment decisions. Study-specific surveys were developed for oncologists and FDRs to explore three major areas: (1) background information (e.g., sociodemographic information, medical practice characteristics, medical history); (2) psychosocial barriers to clinical trial participation; and (3) practical barriers to clinical trial participation.

The Oncologist Survey assessed sociodemographic information, professional setting, board certifications, practice volume, number of prevention trials currently active at a site, and number of patients enrolled in prevention trials in the last twelve months. Interest in participation was assessed by Likert-style questions, “Not at all, “A little”, “Some”, “Moderate”, “A lot”, (e.g., I am interested in offering cancer prevention clinical trials in my practice). Perceived barriers were assessed using two Likert-style questions ranging from “Not at all” to “A lot” (i.e., My medical training taught me to focus on treatment, so I find it difficult to incorporate prevention trials into my practice; In my practice, I do not encounter the kinds of people who are eligible for prevention studies). Physicians also completed a ranking section: “Why physicians do not participate in cancer prevention clinical trials” (5 items, 1 indicating the most important reason and 5 indicating the least important reason).

The FDR Survey assessed sociodemographic information and medical history (i.e., personal and family history of cancer, history of participation in clinical trials, health insurance status). FDRs awareness of cancer prevention clinical trials was addressed by two items: 1) Have you ever heard of cancer prevention clinical trials; or 2) Do you know that there are clinical trials to prevent cancer. FDRs interest in learning more and their willingness to participate in cancer prevention clinical trials were assessed by two items using a five-point Likert-style question ranging from “Not at all” to “ A lot” (i.e., I would participate in a cancer prevention clinical trial if it was offered to me). Barriers to participation in cancer prevention trials were assessed by 32 items using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” to “A lot” (e.g., I believe I can prevent cancer, I would be able to handle the requirements of taking part in a cancer prevention clinical trial, Learning about cancer prevention clinical trials would make me worry about getting cancer, I believe that participating in cancer prevention clinical trials would benefit others). From exploratory factor analysis, in conjunction with face/item validity, three summary subscales of the 32 barrier items were assembled to describe patient perceived and practical barriers to participation in cancer prevention clinical trials (3 subscales: information sources, preferences for prevention approaches, and psychosocial factors). The Information Sources scale refers to five items related to where individuals seek cancer prevention-related information, such as the Internet, news, and family members. Preferences for Prevention Approaches scale refers to seven items related to the extent to which participants would be interested in or open to a variety of specific prevention options, such as vitamins, exercise programs, and oral medication. The Psychosocial Factors scale is comprised of 13 items pertaining to psychosocial factors related to specific beliefs and expectancies about prevention clinical trials (e.g. Learning about clinical prevention trials would make me worry about getting cancer, Participating in a cancer prevention trial would harm me). These subscales were evaluated and confirmed using Cronbach's alphas. Items were reverse scored, when applicable, such that higher scores represent fewer barriers to participation. Since we hypothesized that each group of variables represented a latent construct, we created the summary measures of the items using factor scores from three separate exploratory factor analyses in which just one factor was retained using the separate subscale items. This helped ensure that we found linear combinations of the variables that captured the shared variability of the items and the hypothesized underlying latent construct. Since this project was exploratory in nature and the sample size was small, we did not use confirmatory factor analysis. Table 1 presents the 3 barrier item subscales. For the proportional odds model (see below), participants with higher mean cumulative scores on the Information Source items were labeled more information source seeking/responsive to cancer prevention clinical trial participation. Those with higher scores for the Preferences for Prevention Approaches items were labeled less averse to treatment-based prevention. Those with higher scores for Psychosocial Factors items were considered to have more psychosocial barriers to participation. Finally, FDRs also completed a ranking section: “Why FDRs may not want to participate in cancer prevention clinical trials” (5 items, 1 indicating the most important reason and 5 indicating the least important reason).

Table 1.

First-degree relative perceived and practical barriers to participation in cancer prevention clinical trials subscale items and Cronbach's alphas

| Information Sources Scale Items | α = .89 |

|---|---|

| I would be interested in participating in a cancer prevention clinical trial that: | |

| I heard about on the news | |

| I learned about on the Internet. | |

| A family member told me about. | |

| My doctor told me about. | |

| My relative's cancer doctor told me about. | |

| Preferences for Prevention Approaches Scale Items | α = .92 |

| I would be interested in participating in a cancer prevention clinical trial if: | |

| I had to take vitamins or minerals. | |

| I had to follow a specific diet or exercise program. | |

| It involved complementary or alternative medicine approaches. | |

| I had to take a prescribed medicine by mouth daily. | |

| I had to take an injection in my arm for only three months. | |

| I had to take an injection in my arm each week. | |

| I had to take an injection in my arm each month for the rest of my life. | |

| Psychosocial Factors Scale Items | α =.79 |

| Learning about cancer prevention clinical trials would make me worry about getting cancer. | |

| The thought of participating in clinical research makes me hopeful. | |

| I feel hopeful when I think about how a cancer prevention trial might benefit me in particular. | |

| I find it stressful to think about getting an experimental or investigational treatment. | |

| I would be able to handle the requirements of taking part in a cancer prevention clinical trial. | |

| I believe that participating in a cancer prevention clinical trial: | |

| Would harm me. | |

| Is important to find ways to prevent cancer. | |

| Would benefit me. | |

| Would benefit others. | |

| I believe that: | |

| I would get good care if I participated in a cancer prevention clinical trial. | |

| Taking part in a cancer prevention clinical trial would decrease my risk of getting cancer. | |

| I would get a placebo (sugar pill) if I participated in a clinical trial. | |

| I would be likely to experience side effects if I took part in a cancer prevention clinical trial. | |

Abbreviations: α = Cronbach's alpha

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the demographic and background variables and to characterize responses to measures of: 1) oncologists’ interest in participating in prevention clinical trials; 2) FDRs’ awareness of, interest in, and willingness to participate in prevention clinical trials; 3) both FDRs’ and oncologists’ perceived psychosocial and practical barriers to prevention clinical trial participation; and 4) FDRs’ and oncologists’ ranking sections.

To evaluate willingness to participate, we grouped participants into two categories based on their responses about the degree to which they agree with the statement, “I would participate in a cancer prevention clinical trial if it was offered to me: 1) those who answered “Not at all” or “A little”, or “Some”, grouped as Less Willing, and 2) those who answered “Moderate”, or “A lot” grouped as More Willing (see Table 4). Associations were tested using Fisher's exact test.

Table 4.

Association of cancer prevention clinical trial barrier subscale items to first-degree relative responses to: “I would participate in a cancer prevention clinical trial if it was offered to me.”

| Agreement with the statement, “I would participate in a cancer prevention clinical trial if it was offered to me.”a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer prevention clinical trial barrier subscales and subscale items | Less willing to participateb | More willing to participateb | Total | p |

| 37 (45%) | 45 (55%) | 82 (100%) | ||

| Information Sources | ||||

| I would be interested in a cancer prevention clinical trial that: | ||||

| My relatives cancer doctor told me about. | 11/37 (30%) | 31/44 (70%) | 42/81 (52%) | <0.001 |

| My doctor told me about. | 10/37 (27%) | 31/44 (70%) | 41/81 (51%) | <0.001 |

| A family member told me about. | 4/37 (11%) | 25/44 (57%) | 29/81 (36%) | <0.001 |

| I heard about on the news. | 2/27 (5%) | 13/44 (30%) | 15/81 (19%) | 0.026 |

| I learned about on the internet. | 0/36 (0%) | 8/44 (18%) | 8/80 (10%) | 0.025 |

| Preferences for Prevention Approaches | ||||

| I would be interested in a cancer prevention clinical trial even if: | ||||

| I had to take vitamins or minerals. | 12/37 (32%) | 30/43 (70%) | 42/80 (53%) | <0.001 |

| I had to follow a special diet or exercise program. | 12/37 (32%) | 31/45 (69%) | 43/82 (53%) | <0.001 |

| It involved complementary/alternative medicine approaches. | 9/37 (24%) | 21/44 (48%) | 30/81 (37%) | 0.039 |

| There was a chance of taking a placebo. | 4/37 (11%) | 25/43 (58%) | 29/80 (37%) | <0.001 |

| I might experience side effects from the treatment. | 4/37 (11%) | 16/43 (37%) | 20/80 (25%) | 0.035 |

| I had to take a prescribed medicine by mouth daily. | 2/36 (6%) | 17/44 (39%) | 19/80 (24%) | 0.001 |

| I had to take an injection in my arm for only three months. | 2/37 (5%) | 16/44 (36%) | 18/81 (22%) | 0.003 |

| I had to take an injection in my arm each week. | 1/37 (3%) | 13/43 (30%) | 14/80 (18%) | 0.004 |

| I had to take an injection in my arm monthly for the rest of life. | 2/37 (5%) | 12/44 (27%) | 14/81 (17%) | 0.042 |

| Experimental treatments were riskier than standard approach. | 2/36 (6%) | 12/43 (28%) | 14/79 (18%) | 0.039 |

| Psychosocial Factors | ||||

| I believe that participating in cancer prevention clinical trials: | ||||

| Is important to find ways to prevent cancer. | 20/37 (54%) | 41/45 (91%) | 61/82 (74%) | <0.001 |

| Would benefit others. | 24/37 (65%) | 39/43 (91%) | 63/80 (79%) | 0.009 |

| Would benefit me. | 9/37 (24%) | 37/43 (86%) | 46/80 (58%) | <0.001 |

| Would decrease my risk of cancer. | 3/37 (8%) | 20/44 (45%) | 23/80 (29%) | 0.001 |

| The thought of participating in clinical research makes me hopeful. | 7/37 (19%) | 25/44 (57%) | 32/80 (40%) | 0.003 |

| I feel hopeful when I think about how a cancer prevention clinical trial might benefit me in particular. | 12/37 (32%) | 26/45 (58%) | 38/82 (47%) | 0.006 |

| I would be able to handle the requirements of taking part in a cancer prevention clinical trial. | 6/37 (17%) | 31/44 (70%) | 37/80 (46%) | <0.001 |

| I [do not] believe that participating in a cancer prevention clinical trial would harm me. | 24/37 (65%) | 40/44 (91%) | 64/80 (80%) | 0.006 |

Participants were asked to rate their agreement with statement. Five choices were offered in Likert fashion (Not at all, A little, Some, Moderately, and A lot). “Less willing to participate” includes those responding Not at all, A little, or Some, while “More willing to participate” includes those responding Moderately and A lot.

Column percents for subscale items. Some denominators may be reduced due to non-response by participants.

A 3-category proportional odds (cumulative logit) model (14) was used to examine the influence of collected variables and constructed subscales on level of willingness to participate in a prevention trial. Here, the willingness to participate dependent variable is represented in 3 cumulative levels (“Not at all” and “A little” vs “Some” vs “Moderate” and “A lot”. The three barrier subscales and sociodemographic factors were included as covariates in the cumulative logit models. The subscales were each centered on the mean and standardized to have a variance of 1. The sociodemographic factors included sex, age entered as a natural cubic spline with 2 internal knots to allow for a flexible relationship, whether a person had attended some college or more (education), whether an individual was married or partnered, the number of relatives of the FDR with cancer, how often the FDR is involved with the care of the index patient (answered in increments from never to daily with the variable entered as a continuous variable), and whether the FDR is employed or seeking employment (compared to those not seeking employment due to retirement, disability, or other reasons). Proportionality was tested by Brant's method (15). Similarities in rankings were examined using Kendall's statistic (16) and the related approximate p-value as implemented in STATA 9.0.

Results

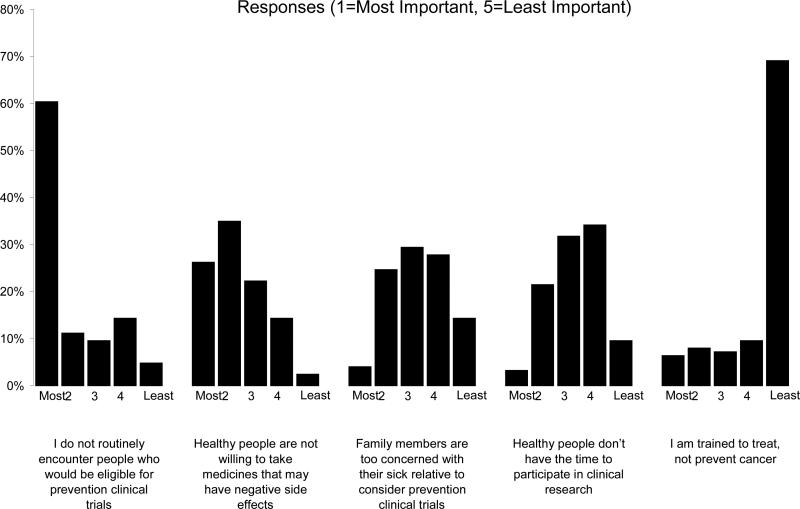

A total of 137/478 physician surveys were completed and returned (29% participation rate). Physicians were primarily white (86%), and approximately 2/3rds (63%) practiced in a private practice or community-based setting. Physician demographic and practice characteristics are presented in Table 2. Sixty-six percent of physicians indicated that they were (“Moderately” or “A Lot”) interested in offering cancer prevention clinical trials to their patients. The majority (79.4%) indicated “Not at All” or “A little” to “My medical training taught me to focus on treatment, so I find it difficult to incorporate prevention trials into my practice”, while 42% of physicians agreed “Moderately” or “A Lot” to “In my practice I don't encounter the kinds of people who are eligible for prevention studies”. To assess how perceived barriers among oncologists impact their interest in having patients participate in cancer prevention clinical trials, we examined associations between interest and barriers. No statistically findings were identified (data not shown). Figure 1 summarizes physician responses to the survey items in which they were asked to rank barriers to participation in clinical prevention trials. There was a statistically significant similarity in the average oncologists’ rankings across the questions(p<0.001).

Table 2.

Oncologist Demographic and Practice Characteristics (N = 137)

| Median | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(Years) | 49 | 32 | 71 |

| Demographic | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 111 | 81% | |

| Female | 26 | 19% | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 | 1% | |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 134 | 99% | |

| Race | |||

| White | 118 | 86% | |

| Asian | 14 | 10% | |

| African American or Black | 2 | 1.5% | |

| Native American/Pacific Islander | 2 | 1.5% | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1% | |

| Professional Setting | |||

| Private practice or community/other hospital-based | 85 | 62% | |

| Academic Medical Center | 52 | 38% | |

| Board certified: | |||

| Medical Oncology | 124 | 91% | |

| Hematology | 80 | 59% | |

| Practice a | Median | Quartiles | |

| Oncology patients seen in the past year | 700 | 400,2000 | |

| New oncology patients in past year | 200 | 100,300 | |

| Patients on cancer prevention clinical trials | 0 | 0,10 | |

| Active prevention clinical trials | 2 | 2,5 | |

Abbreviations: Min, minimum; Max, maximum

Includes all oncology patients in each provider practice

Figure 1.

Reasons Why Oncologists Do Not Participate in Clinical Prevention Trials. (N=126) (p<0.001)a

a Items were ranked by participants. P-values test the null hypothesis that there is no association among individuals’ rankings.

One hundred forty-five FDRs were identified by their patient relatives, and 129 (89%) were determined to be eligible and were subsequently mailed surveys, The 16 ineligible participants were either not first-degree relatives (e.g., husbands/wives) of the patient or were < 18 years old. Eighty-two eligible FDRs responded (64%). Background variables are described in Table 3. Awareness of cancer prevention clinical trials was modest among FDRs. Twenty-four out of eighty-two (29%) FDRs had not heard of clinical trials, and thirty-seven (45%) indicated that they did not know that there are clinical trials to prevent cancer. Despite low awareness, FDRs were open to the idea of participation in a cancer prevention clinical trial. Many FDRs expressed interest in learning about cancer prevention clinical trials (68% responded “Moderately” or “A Lot”) as well as a willingness to participate (55% responded “Moderately” or “A Lot”).

Table 3.

First-degree relative background and demographic characteristics(N = 82)

| Median | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(Years) | 46 | 18 | 83 |

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 23 | 28% | |

| Female | 59 | 72% | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| No response | 7 | 9% | |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 75 | 91% | |

| Race | |||

| White | 73 | 89% | |

| Non-white | 9 | 11% | |

| Education | |||

| High School or Below | 31 | 38% | |

| Above High School | 51 | 62% | |

| Marital | |||

| Married | 48 | 59% | |

| Not Married | 33 | 40% | |

| No response | 1 | 1% | |

| Employment | |||

| Working | 63 | 77% | |

| Not Working | 19 | 23% | |

| Income | |||

| <$30,000 | 34 | 42% | |

| ≥$30,000 | 43 | 53% | |

| No response | 5 | 6% | |

| Health Insurance | |||

| Yes | 73 | 89% | |

| No | 8 | 10% | |

| Relatives with Cancer | |||

| 1 | 33 | 40% | |

| 2-3 | 36 | 44% | |

| >3 | 13 | 16% | |

| How often are you involved in the care of your relative (the index patient)? | |||

| Never | 14 | 17% | |

| Rarely | 17 | 21% | |

| Monthly | 13 | 16% | |

| Weekly | 18 | 22% | |

| Daily | 19 | 23% | |

| No response | 1 | 1% | |

Three subscales of perceived and practical barriers to participation in cancer prevention clinical trials were developed from individual items from the survey (Information Sources, Preferences for Prevention Approaches, and Psychosocial Factors) (see Methods and Table 1). To assess how practical and perceived barriers to cancer prevention clinical trials may modulate willingness to participate in this type of research, associations between FDR willingness to participate in prevention clinical trials and the individual barrier subscale items were examined (Table 4). In general, participants reporting a higher willingness to participate in a prevention trial (45/82)(55%) more commonly responded positively to the items within the three subscales. Trials involving vitamins and exercise were viewed most favorably (42/80 or 53% of participants overall expressed interest, including 37/43 or 70% of the More Willing to Participate group). Certain items distinguished those who were more willing to participate from those who were less willing. For example, 37/42 (86%) of those More Willing to Participate agreed with the statement “I believe that participating in a cancer prevention clinical trial would benefit me,” while only 9/37 (24%) of those Less Willing to Participate agreed similarly (p<0.001). This disparity was less pronounced for statements that implied greater burdens associated with treatment duration. For example, only 2/37 (5%) participants Less Willing to Participate and only 12/44 (27)% of participants More Willing (p=0.042) answered that they agreed moderately or a lot with the statement, “I would be interested in participating in a cancer prevention clinical trial if I had to take an injection in my arm monthly for the rest of my life”, suggesting that cancer prevention clinical trial participation interest may diminish as the demands of a trial increase, even among those with a greater willingness to participate. FDRs overall perceived a low personal risk of participating in a clinical trial (64/80 or 80% agreed “I do not believe that participating in a cancer clinical trial would harm me) and a large benefit to others (63/80 or 79% agreed “I believe that participating in a cancer prevention clinical trial would benefit others”), but did not anticipate that participation would lower their own risk of cancer (29% agreed with “I believe taking part in a cancer prevention clinical trial would decrease my risk of getting cancer.”)

In the proportional odds model (Table 5), interest in learning about clinical prevention trials from more information sources (i.e. more information source responsive) was associated with being more willing to enroll in clinical trials (OR=3.36, 95% CI 1.04-10.84). Similarly, having fewer psychosocial barriers was associated with a greater willingness to participate in cancer prevention clinical trials (OR=2.47, 95% CI 1/15-5.31). None of the potentially confounding factors was significant. The Brant test of the proportional odds model was non-significant (i.e., the null hypothesis was not rejected, proportional odds of the effects is assumed).

Table 5.

Association of cancer prevention clinical trial barrier subscales and demographic factors to interest in first-degree relatives in participation in a cancer prevention clinical trial (n=60 complete data)a

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Information sources scale | 3.36b | (1.04,10.84) |

| Preferences for prevention approaches scale | 0.97c | (0.38,2.48) |

| Psychosocial factors scale | 2.47d | (1.15,5.31) |

| Confounders | ||

| Sex (Female) | 0.94 | (0.25,3.61) |

| Age | 1.12 | (0.90,1.39) |

| Education (Some college) | 0.96 | (0.29,3.17) |

| Married/partnered | 2.55 | (0.63,10.36) |

| Number of relatives with cancer | 1.27 | (0.54,3.00) |

| How often FDR is involved with care of patient | 0.92 | (0.59,1.44) |

| Employed/seeking employment | 0.20 | (0.01,3.29) |

Cumulative logistic regression slope estimates for 3-level ordinal variable: “I would participate in a cancer prevention clinical trial if it was offered to me.”

Odds ratio for individuals who are more information source responsive versus less

Odds ratio for individuals who are less averse to treatments versus more

Odds ratio for individuals who report fewer psychosocial barriers versus more

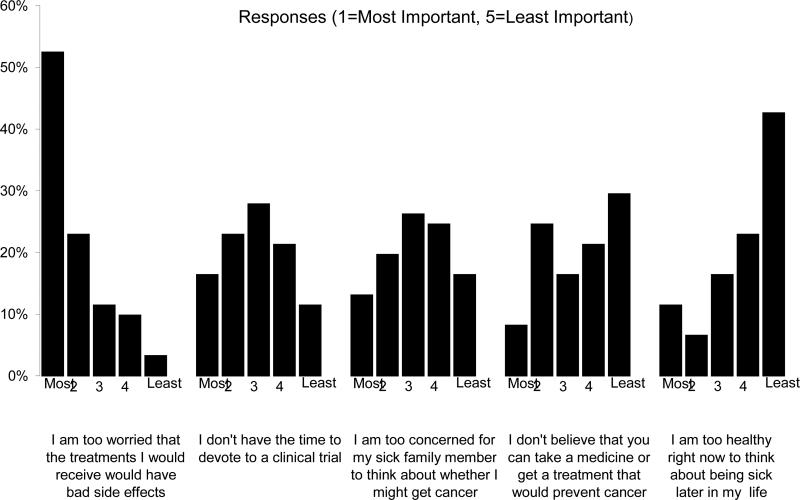

FDR-ranked barriers to participation in prevention trials are summarized in Figure 2. FDRs ranked “worry about side effects” and lack of time to devote to participation in a cancer prevention clinical trial as the most important barriers to participation in prevention trials. A significant similarity in the individual rankings by oncologist across the questions was seen (i.e. oncologists had similar ordered perceptions of barriers)(p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Reasons Why FDRs Do Not Participate in Clinical Prevention Trials. (N=61) (p<0.001)a

a Items were ranked by participants. P-values test the null hypothesis that there is no association among individuals’ rankings.

Discussion

The data from this sample demonstrate that almost 50% of individual who have a first-degree relative (FDR) with cancer and who may themselves be at increased risk of cancer are unaware of the availability of clinical cancer prevention trials. However, many (68%) of these individuals are interested in learning more about cancer prevention clinical studies, and do not consider themselves “too healthy” to think about being sick later in life. Furthermore, many FDRs perceive a low personal risk associated with participating in clinical prevention trials and a large benefit for others. These results support the need to develop educational interventions that capitalize on the “teachable moment” (17) that exists when a physician interacts with an FDR of a patient under treatment for cancer. A large part of the information may be provided by primary care physicians or oncologists who interact with these FDRs, since many FDRs expressed interest in hearing about prevention trials from their relative's oncologist (52%) or their own doctor (49%). Given that FDR's are unaware of prevention clinical trials and are concerned about side-effects and the time needed for participation, interventions are needed to increased awareness and to address specific beliefs and expectations. Past research from our group guided by the C-SHIP model has found that tailored messages to specific barriers can increase adherence to follow-up recommendations among individuals who are at higher risk for cancer (18).

FDRs of cancer patients identified concern about side effects and time demands of a cancer prevention clinical trial as the foremost barriers to participation. These data parallel those from cancer patients who also identify potential side effects as the primary barrier to participation in treatment clinical trials (12). Previous studies have documented concerns regarding the negative impact on health coupled with a reduction in intention to participate when more side effects are discussed (19-23). These issues must be carefully considered during study development because of the negative impact that side effects of a proposed intervention may have on prevention trial enrollment. Researchers should additionally strive to keep study time requirements to a minimum while still properly executing the study, given that most individuals who are eligible for prevention trials are generally healthy and have time-intensive obligations to consider, such as those related to work and family.

The low survey participation rate among oncologists (29%) limits the interpretation of this portion of the study. Nonetheless, despite interest in being involved in cancer prevention clinical trials, many oncologists felt that they did not have contact with the type of patient that may be eligible for a cancer prevention clinical trial (60% ranked this as the most important barrier, Figure 1). This finding may indicate a need to increase awareness among oncologists of large US prevention trials that target individuals with a history of in situ cancer (e.g. National Surgical Adjuvant Bowel Project or NSABP P-1 trial which enrolled women with lobular carcinoma in situ) or survivor populations (e.g. upcoming NSABP P-5 trial which will enroll individuals with resected Stage I or II colorectal cancers). Oncologists also highly ranked participation barriers related to side effects of preventive medicines in healthy people (25% ranked this as the most important). Physician-perceived barriers to cancer prevention clinical trials have been reported in two large US surveys of medical oncologists (24,25). Both studies found high perceived barriers related to inadequate access to an appropriate cancer prevention population (second highest reported barrier in each study).

Our study has several limitations. First, participation rate among physicians was low (29%) and participating physicians served a select (primarily white, educated, insured) population, narrowing generalizability of the study findings, but reflecting previously encountered barriers in studying physicians’ opinions seen in two large surveys examining opinions related to cancer prevention (24,25). Nonetheless, oncologist and index patient demographics were similar to those in the general statewide populations, although non-white cancer incidence in Pennsylvania is 9.5%, slightly lower than the study's sample of 14% (26-28). Second, among FDRs, non-response bias may have been introduced such that FDRs who responded were more interested in prevention trials, had a higher likelihood of having heard of prevention trials, and were more willing to take part in prevention clinical trials. Variability in the number of FDRs participating per patient could also have introduced additional bias. Analyses to examine clustering by provider or index patient could not be performed as the data to examine this was not collected. Finally, external data were also not available to validate the perceived psychosocial and practical barriers subscales used in the multivariable analyses. Hence, the clinical relevance of a one standard deviation change in the subscales on general patient characteristics or outcomes is unclear. These data must therefore be viewed as exploratory. Nevertheless, this is the first study to our knowledge to simultaneously examine provider and patient barriers to prevention clinical trial participation, and to show that potential trial participants who are more receptive to information from professional, media, or internet sources and those with fewer psychosocial barriers would be more likely to participate in a prevention trial if it was offered to them.

The purpose of this study was to obtain preliminary data that could inform development of a model of barriers to participation in prevention clinical trials. The results have implications for designing messages for recruiting participants into cancer prevention studies, as well as for the design of studies themselves. A key component of future research for prevention clinical trials should focus on the process of educating target individuals about the availability, potential risks (e.g. side effects), and potential benefits of prevention trial participation. Researchers developing cancer prevention strategies must recognize that eligible individuals with low interest in prevention clinical trials may express low interest in prevention trial participation no matter the treatment type, perceived societal benefit, or safety associated with the trial, and may therefore require more tailored education about prevention trials. On the other hand, those potential participants with moderate to high interest may have specific information sources (e.g.physician>media/internet) or treatment parameters (e.g. preference for lower side effects) that will markedly influence participation rates despite baseline strong interest in learning about prevention trials.

Understanding current barriers to participation in prevention clinical trials has important implications for future cancer research. A growing understanding of cancer biology and pathogenesis has led to the identification of novel molecular pathways that in some cases serve as indicators of cancer risk. To take full advantage of the information afforded by these potential classifiers, the demand for well-designed validation studies with cancer prevention endpoints will only continue to grow. Efforts to increase participation in prevention trials through improved understanding of patient and provider barriers to participation are crucial to meet the growing needs of the cancer research community and to promote better clinical care through targeted cancer prevention strategies.

Condensed abstract.

First-degree relatives of cancer patients are poorly informed about cancer prevention clinical trials. Nonetheless, they perceive low personal risk and are interested in learning more.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Pennsylvania Department of Health (PDOH) (ME# 02-285), the Biostatistics Core Facility and the Behavioral Research Core Facility of P30CA06927 from the NCI. PDOH specifically disclaims responsibility for analyses, interpretations, or conclusions. The authors report no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Comis RL, Miller JD, Aldige CR, Krebs L, Stoval E. Public attitudes toward participation in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:830–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis PM. Attitudes towards and participation in randomised clinical trials in oncology: a review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:939–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1008342222205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis PM, Butow PN, Simes RJ, Tattersall MH, Dunn SM. Barriers to participation in randomized clinical trials for early breast cancer among Australian cancer specialists. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:486–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go RS, Frisby KA, Lee JA, et al. Clinical trial accrual among new cancer patients at a community-based cancer center. Cancer. 2006;106:426–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman DP, Schoenbaum ML, Potosky AL, et al. Measuring the incremental cost of clinical cancer research. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:105–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klabunde CN, Springer BC, Butler B, White MS, Atkins J. Factors influencing enrollment in clinical trials for cancer treatment. South Med J. 1999;92:1189–93. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199912000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lara PN, Jr., Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1728–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lara PN, Jr., Paterniti DA, Chiechi C, et al. Evaluation of factors affecting awareness of and willingness to participate in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9282–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, Gillespie W, Russell I, Prescott R. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1143–56. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siminoff LA, Zhang A, Colabianchi N, Sturm CM, Shen Q. Factors that predict the referral of breast cancer patients onto clinical trials by their surgeons and medical oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1203–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung NS, Crowley WF, Jr., Genel M, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289:1278–87. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meropol NJ, Buzaglo JS, Millard JL, et al. Psychosocial barriers to clinical trial participation as perceived by oncologists and patients. JNCCN. 2007;5:753–62. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller SM, Diefenbach M. C-SHIP: A cognitive-social health information processing approach to cancer. In: Krantz D, editor. Perspectives in behavioral medicine. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah,NJ: 1998. pp. 219–244. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression, Second Edition. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brant R. Assessing proportionality in the proportional odds model for ordinal logistic regression. Biometrics. 1990;46:1171–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendall MG, Smith BB. The problem of M rankings. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1939;10(3):275–287. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawson PJ, Flocke SA. Teachable moments for health behavior change: A concept analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.002. doi:10.10016/j.pec.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller SM, Shoda Y, Hurley K. Applying cognitive-social theory to health-protective behavior: breast self-examination in cancer screening. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:70–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandelblatt J, Kaufman E, Sheppard VB, et al. Breast cancer prevention in community clinics: will low-income Latina patients participate in clinical trials? Prev Med. 2005;40:611–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchbinder SP, Metch B, Holte SE, Scheer S, Coletti A, Vittinghoff E. Determinants of enrollment in a preventive HIV vaccine trial: hypothetical versus actual willingness and barriers to participation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:604–12. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200405010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Connell JM, Hogg RS, Chan K, et al. Willingness to participate and enroll in a phase 3 preventive HIV-1 vaccine trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31:521–8. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starace F, Wagner TM, Luzi AM, Cafaro L, Gallo P, Rezza G. Knowledge and attitudes regarding preventative HIV vaccine clinical trials in Italy: results of a national survey. AIDS Care. 2006;18:66–72. doi: 10.1080/09540120500161777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halpern SD, Metzger DS, Berlin JA, Ubel PA. Who will enroll? Predicting participation in a phase II AIDS vaccine trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:281–8. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chlebowski RT, Sayre J, Frank-Stromborg M, Bulcavage Lillington L. Current attitudes and practice of American Society of Clinical Oncology-member clinical oncologists regarding cancer prevention an control. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(1):164–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganz PA, Kwan L, Somerfield MR, Alberts D, Garber JE, Offit K, Lippman SM. The role of prevention in oncology practice: results from a 2004 survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology members. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2948–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts. [March 18, 2010];Data derived from Population Estimates, 2000 Census of Population and Housing, 1990 Census of Population and Housing, Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates, Country Business Patterns, 1997 Economic Census, Minority- and Women-Owned Business, Building Permits, Consolidated Federal Funds Report, 1997 Census of Governments [Internet]. 02.2005. Available at http:quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/42000.html.

- 27.Pennsylvania Department of Health [March 18, 2010];EpiQMS. Available at http://app2.health.state.pa.us/epiqms.

- 28.Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Health Statistics and Research [March 18, 2010];Number of cancer case by county, age, sex and race, by 23 primary sites. Pennsylvania residents 2003. Available at http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/health_statistics_and_research/11599.