Abstract

Although spatial language and spatial cognition covary over development and across languages, determining the causal direction of this relationship presents a challenge. Here we show that mature human spatial cognition depends on the acquisition of specific aspects of spatial language. We tested two cohorts of deaf signers who acquired an emerging sign language in Nicaragua at the same age but during different time periods: the first cohort of signers acquired the language in its infancy, and 10 y later the second cohort of signers acquired the language in a more complex form. We found that the second-cohort signers, now in their 20s, used more consistent spatial language than the first-cohort signers, now in their 30s. Correspondingly, they outperformed the first cohort in spatially guided searches, both when they were disoriented and when an array was rotated. Consistent linguistic marking of left–right relations correlated with search performance under disorientation, whereas consistent marking of ground information correlated with search in rotated arrays. Human spatial cognition therefore is modulated by the acquisition of a rich language.

Keywords: spatial language, language and thought, Nicaraguan Sign Language

The cognitive capacity to represent space is crucial for basic survival and underpins a host of human achievements, from technology to science to mathematics. Although many elements of spatial cognition are shared between humans and nonhuman species, some aspects of human spatial cognition have been argued to depend on language (1–5). This claim, however, continues to be debated (6, 7). A community of individuals in Nicaragua developing a new sign language allows us to test for effects of language on spatial cognition, to ask whether such effects persist into adulthood, and to examine whether nonlinguistic experience can overcome language limitations.

Studies of the relationship between language and cognition have taken one of two approaches. The developmental approach assesses spatial cognition in young children before they have acquired the relevant spatial language (2). The cross-linguistic approach compares the spatial cognitive abilities of speakers of different languages, including languages that encode spatial relations in different ways (4, 3, 8). Although the cumulative evidence suggests some relationship between language and spatial cognition, findings from both approaches are open to alternative interpretations. In developmental studies, immature cognitive skills typically are accompanied by less developed language skills and so either language or cognitive development could explain improvements in spatial abilities. Cross-linguistic studies face another confound: speakers of different languages often differ in other crucial ways, such as in their experience with maps, long-distance travel, and contact with nature. Therefore, any observed variation in spatial abilities might be the consequence of cultural rather than linguistic differences (6). For these reasons, the role of language in spatial cognition remains controversial (5–9).

The language and spatial abilities of deaf users of Nicaraguan Sign Language (NSL) provide a test case for theories about spatial language and cognition by allowing us to disentangle language abilities from cognitive maturation and cultural practices. NSL first appeared in the 1970s among a cohort of deaf children entering special education schools, and is now used by approximately 1,000 signers (10, 11). The first cohort of children, those of the 1970s and early 1980s, developed an early form of the language, which was expanded by a second cohort of children in the mid-1980s. Today, the language of the second-cohort signers is more advanced than that of the first-cohort signers (12–16).

Both cohorts share the same culture and environment (the capital city, Managua). Furthermore, members of both cohorts are well past childhood conceptual development, and all participants in the current study were exposed to NSL before the age of 6. Thus, this population provides a natural experiment in which language level varies systematically, but culture, cognitive maturation, and age of exposure to a native language are equated. This rare combination allows us to isolate effects of language on spatial cognition.

Under some conditions of disorientation, the ability to navigate in space using landmarks seems to be related to language. Humans, like other species, readily use geometric information to guide their navigation after they are disoriented (2, 6), but their proficient and flexible landmark use does not emerge until age 5 under many circumstances, and its emergence correlates with the productive mastery of the phrases “left of X” and “right of X” (2, 17–19). Further, adults’ landmark use after disorientation is impaired when they engage in a language repetition task in a small, enclosed environment (1, 20).

Left–right language has also been implicated in an implicit rule-learning task using a tabletop array (21). Speakers of a language that uses allocentric spatial expressions (e.g., “north of me”) and great apes from a variety of species all found it more difficult to learn a table-top pattern that maintained egocentric spatial relations (e.g., to the participant's left) than allocentric ones (e.g., to the north). By contrast, Dutch speakers, who primarily use relative spatial language (e.g., “to my left”), learned both kinds of spatial relations equally well. Given these patterns of data, one role of spatial language may be to support the specific use of egocentric (i.e., left–right) reference frames, particularly within small enclosures or with arrays of small objects.

In addition, at least some kinds of nonlinguistic experience can improve performance on spatial tasks. In larger-sized arenas, disoriented children are more apt to attend to landmarks (22), and verbal interference has smaller effects for adults (23), suggesting that navigation in larger scale spaces may benefit from cognitive mechanisms that are less language-dependent. Nonhuman animals can integrate feature information after extensive training (24, 25) and goldfish can do so when an escape instead of a foraging paradigm is used (26). Nevertheless, the performance of children and nonhuman animals, even after training, does not show the spontaneous cognitive flexibility shown by human adults with mature language. Because adult humans do not require any training to solve any of these reorientation tasks, it is possible that such cognitive flexibility is crucially tied to language.

Sign languages provide a unique window into the relation between language and spatial cognition because they differ from spoken languages in how spatial relations are linguistically marked. Instead of using spatial terms such as “in” or “left,” sign languages use signing space to represent spatial relations iconically. Signers create a representation in which real-world spatial relations are mapped onto the relative positions of their hands. For example, to describe a cat on a table, a signer would place one hand representing the cat onto the other hand representing the table, with no separate sign (e.g., “on”) that labels the spatial relation. Left-right relations are also marked by the positions of the hands in signing space. Within this system, signers can represent a scene either from their own perspective (describing an object to the right by producing a sign on their right side) or from the perceiver's perspective (describing an object to the right by producing a sign on their left side). In most sign languages signers choose to represent the scene from their own perspective (27, 28).

NSL has not yet converged on a spatial strategy like the one found in most established sign languages. Individual first-cohort signers are inconsistent in marking left–right relationships; objects on the left side are represented sometimes with signs on the left, and sometimes with signs on the right. Consequently, the first cohort's utterances are ambiguous with respect to left–right relations. Second-cohort signers are mixed as a group and will negotiate a strategy for each conversation, but as individuals they tend to be consistent in their chosen strategy (15). In essence, first-cohort signers appear to lack the device that has previously correlated with children's performance on nonverbal spatial tasks—a consistent linguistic marker specifying left–right relations.

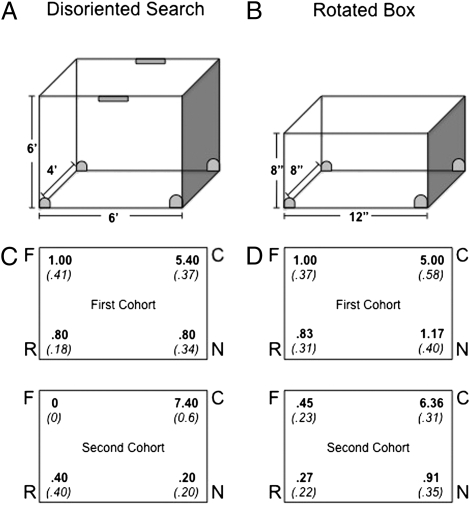

To test whether language supports spatial cognition, we compared first- and second-cohort signers’ performance on two spatial tasks that require the use of a landmark, a brightly colored wall, to find a hidden object. In the disoriented search condition (17), participants entered a small, enclosed room with a single red wall as a landmark (Fig. 1A). For each trial, they watched an experimenter hide a token in one corner, and then were blindfolded and turned slowly until disoriented. They then removed the blindfold and indicated the corner where they thought the token was hidden. In the rotated box condition (Fig. 1B), the procedure was similar: the token was hidden in a small-scale tabletop model of the room, the participant was blindfolded, and the model (not the participant) was turned. There were eight trials per condition, two in each corner.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the apparatus for (A) the disoriented search condition (small gray rectangles indicate the locations of the lights) and (B) the rotated box condition. Both apparatuses had one red wall, shaded gray in the diagram. The first and second cohort's search patterns in (C) the disoriented search condition and (D) the rotated box condition. Mean search responses (out of 8) are in bold, and SDs are in italics (C= correct search, N = near corner error, R = rotational corner error, F = far corner error). The first and second cohort scores overlapped in only one case in the disorientation condition (first cohort: range = 4–6, second cohort: range = 5–8), and in four cases in the rotated box condition (first cohort: range = 3–7, second cohort: range = 5–8). Second-cohort signers significantly outperformed first-cohort signers on both tasks.

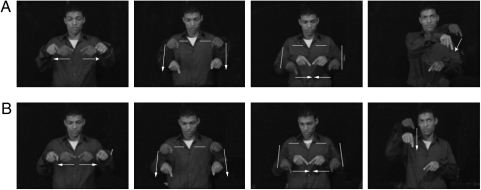

After each condition, participants provided language samples describing the hiding locations used in the room and in the box “so that another person could find it” (Fig. 2). In our analysis of the language samples, we selected five aspects of spatial language that could arguably support spatial cognition and that are relevant to this elicitation task (Table 1). For example, the simultaneous presentation of figure and ground linguistically encodes one object relative to another but only the consistent location of a left-hand object with respect to the location of a right-hand object provides the additional information of “left of.” Furthermore, the explicit mention of the red wall indicates linguistic encoding of landmark information. This may be sufficient for remembering the target location if geometric information (e.g., whether the target corner was to the left or right of a long wall) can be processed nonlinguistically (6). Finally, locating the red wall in a consistent location in signing space across multiple trials indicates the generation of a stable mental image of spatial relations, previously linked to enhanced spatial abilities of signers (29). Three fluent signers with knowledge of NSL coded the descriptions.

Fig. 2.

A second-cohort signer describing the gaming token located (A) to the left of the red wall and (B) to the right of the red wall. In both descriptions, he provides ground information by drawing a rectangle representing the box. Importantly, he linguistically distinguishes left from right, locating the token on the left to his left, and the token on the right to his right.

Table 1.

Measures of spatial language

| Measure | Description |

| Mentioning a ground | Does the participant mention the ground of the spatial relationship (e.g., a wall?) |

| Simultaneous mention of figure and ground | Does the participant simultaneously articulate the figure (e.g., token) relative to the ground (e.g., wall)? |

| Mentioning the red wall | Does the participant explicitly mention the red wall? |

| Consistency of placement of the red wall | Across four trials does the participant locate the red wall in a consistent location? |

| Consistency in marking left–right relations | Across four trials does the participant locate left and right spatial relationships consistently? |

If adult-like performance on the spatial tasks depends on biological maturation or on total years of experience navigating the world, then the two cohorts should exhibit equivalent performance or the first cohort should show an advantage over the second. Furthermore, sign language use has been shown to enhance spatial cognition independently of deafness (29–31). For this reason, first-cohort signers, who have more years of signing experience, might be expected to perform better than second-cohort signers on spatial tasks. Alternatively, if spatial cognition depends on the acquisition of particular linguistic markers introduced by the second cohort but not (or not yet) acquired by the first cohort, then the second cohort should show an advantage over the first cohort. Such a finding would demonstrate that failure to acquire the requisite language limits performance in a way that life experience does not fully replace.

Results

The second cohort significantly outperformed the first cohort in both the disoriented search condition (Fig. 1C; Mann-Whitney U = 3.5, P = 0.04) and the rotated box condition (Fig. 1D; Mann-Whitney U = 14, P = 0.05), indicating that limitations in spatial cognition can persist into adulthood. Evidently, 30 y of experience navigating in the world did not give first-cohort signers the tools to perform as well as second-cohort signers. Importantly, all first-cohort signers succeeded on two pretest familiarization trials where memory for topological spatial relationships was tested using an identical procedure (mean = 2, SD = 0), suggesting that their poorer performance was not due to memory impairments, failure to encode basic spatial relations, or difficulty understanding the task instructions.

Further analyses compared signers’ specific spatial language to their search performance. Signers’ consistency in marking left–right spatial relationships correlated with success in the disoriented search condition (Table 2). By contrast, this aspect of language did not correlate with success in the rotated box condition. Rather, consistency in placing the red wall in signing space correlated with success in the latter condition (Table 2). No other feature of spatial language correlated with performance on either spatial task, and the spatial tasks did not correlate with each other (rs = 0.47, P = 0.20).

Table 2.

Correlations between spatial language measures and performance on the spatial tasks

| Disoriented search | Rotated box | |

| Mentioning a ground | 0.09 | 0.24 |

| Simultaneous mention of figure and ground | 0.54 | 0.39 |

| Mentioning the red wall | −0.14 | 0.38 |

| Consistency of placement of the red wall | 0.45 | 0.64* |

| Consistency in marking left–right relations | 0.62† | 0.40 |

*P = 0.006.

†P = 0.05.

The results from the disoriented search condition are consistent with previous findings of a correlation between the acquisition of “left of” and “right of” in English and the successful use of a landmark on this task (17), suggesting that the underlying mechanism is common to signed and spoken languages. This result supports the idea that left–right language is beneficial for representing egocentric spatial relations between objects (e.g., an object to the left of a landmark). However, the first cohort's performance differs from that of English-speaking children. First, although toddlers’ search accuracy usually falls under 40% in comparable set-ups (17), first-cohort adults’ performance was considerably better [mean = 68%, t(4) = 3.5, P = 0.02]. Second, children's errors usually cluster at the corner diagonally opposite the correct corner, indicating that they use the geometry of the room but fail to incorporate landmark information. In contrast, the first cohort's errors were evenly distributed across the three incorrect corners (Fig. 1C).

The relatively high performance of first-cohort signers suggests that either maturation or some aspects of linguistic, cultural, or cognitive experience can facilitate the use of visual cues under conditions of disorientation. Indeed, their use of language is superior to that of a young child: They readily encode complex information and tell extended narratives (14, 16). In addition, the first-cohort signers are adults who may be able to draw on several cognitive mechanisms in their attempts to work out the task. Their errors, however, indicate that they do not rely on the geometry of the room to solve the problem. The characteristic reliance on the geometry of the room reflects a rapid, automatic process—children rarely experience the disorientation task as difficult, making their search decisions very quickly. In contrast, first-cohort participants made their decisions slowly and with effort, taking as long as nine seconds and reporting that the task was difficult. These observations suggest that the first-cohort signers had an ambiguous representation of the hiding event in memory and, unlike children, were aware of their own uncertainty of the correct response. Their slower and more effortful error responses are unlike the fast, automatic error responses that characterize reliance on the geometry of the room. Nevertheless, the first cohort's performance in the disoriented search condition was significantly below the second cohort's performance, and correlated with left–right language. This result clearly indicates that language plays a role beyond that of maturation and experience.

The correlation between language and search performance in the rotated box condition likely reflects different processes and may be specific to signed languages. Second-cohort signers systematically placed a sign for the ground object (the red wall) in their signing space and reused that location across their four descriptions. First-cohort signers, by contrast, placed signs for the red wall in different locations across the four trials. The typical devices for expressing spatial relations in sign languages require signers to generate a mental spatial configuration and to maintain it across several signs, in order to map these configurations consistently onto signing space. Deaf and hearing users of American Sign Language (ASL) exhibit advantages in mental image generation and transformation compared with nonsigners, indicating a strong link between sign language experience and mental imagery abilities (29–31). A similar link is evident here. The consistency and systematicity of the second-cohort signers’ spatial language may have facilitated their mental imagery abilities and, consequently, their performance in the rotated box condition. Importantly, performance in this condition did not correlate with left–right language. The small box is a single object seen from a bird's-eye perspective. By contrast, the disorientation chamber, a space within which participants moved, was seen from an egocentric perspective. In the rotated box task, aligning the actual red wall of the small box with that of their mental image may have been sufficient to support the mental rotation required to identify the hiding location.

Discussion

Taken together, the present findings provide evidence for a causal effect of language on thought. Consistent spatial language is necessary for some aspects of mature spatial reasoning, even for adults who routinely navigate through a complex urban environment. The current analyses rule out accounts of the correlation between language and cognition that appeal to cultural, rather than linguistic, effects (7). They also eliminate the explanation that spatial skills decline because they are not useful in the participants’ environment (32). Finally, these results cannot easily be explained by a general cognitive deficit specific to first-cohort signers. Indeed, we predict that both cohorts would use geometric cues equally well in the disorientation condition if the red wall were removed. Further, a general cognitive deficit would not explain the specificity of the relationship between each task and linguistic mechanism nor the lack of a correlation between the spatial tasks.

The present findings cannot identify the mechanism by which language supports spatial cognition, although there is no shortage of candidates. Language may serve as a medium of spatial representation (33), as an aid to cognitive processing (34), or as an anchor for systematizing spatial concepts that are otherwise ephemeral (35). These findings also do not reveal whether consistent spatial language and its resulting cognitive benefits can be acquired in adulthood. In typically developing children, acquiring either a spoken or signed language, spatial language is usually mastered after the age of four, later than many other aspects of language (36, 37). A previous study with Nicaraguan signers reported that first-cohort signers’ late acquisition of words like “think” and “know” predicted their subsequent theory-of-mind development in adulthood (38). In the case of spatial cognition, the limits of adult acquisition remain unclear. Evidence from late learners of ASL suggests that those who begin to acquire spatial language later in life may never fully master it (39).

Differences between successive cohorts of Nicaraguan signers reveal that specific domains of spatial cognition depend on specific linguistic devices that are well instantiated in mature languages. As language evolved, spatial cognition may have correspondingly become dependent on combinatorial linguistic devices. Today, modern human adults whose newly emergent language lacks such devices struggle when faced with a simple spatial puzzle. However, as the language is transformed, so are the spatial abilities of its newest and youngest learners.

Methods

Participants.

Sixteen deaf signers were tested individually in a disoriented search condition (first cohort: Mage = 31.35, SD = 3.79, males = 3, females = 2; second cohort: Mage = 20.92, SD = 1.91, males = 3, females = 2) and a rotated box condition (first cohort: Mage = 31.35, SD = 3.75, males = 4, females = 2; second cohort: Mage = 20.60, SD = 2.83, males = 7, females = 4). Eleven of the 16 signers completed both conditions, in which case the disorientation condition was always administered first. Four additional second-cohort signers were excluded because local power outages prevented them from completing all of the disorientation trials; the trials they did complete resulted in successful searches. One first-cohort signer completed only four trials; a score out of eight trials was derived by applying the percentage correct (75%) from that participant's first four trials. This derived score is supported by the performance of the other participants: all participants who made one error in the first four trials made at least one error in the second four trials.

Disoriented Search Condition.

Following Hermer and Spelke (17), participants in the disoriented search condition entered a 4’ wide × 6’ long × 6’ high (1.22 m × 1.83 m × 1.83 m) rectangular room (Fig. 1A) constructed from ten 24” × 36” (0.61 m × 0.91 m) commercially available connected panels (Panel Plus System, Monster Displays). The interior of the apparatus was gray felt with one short wall entirely covered in smooth red fabric. The entrance was a panel in one of the long walls farthest from the red wall. Once closed, the door was indistinguishable from the other gray panels. The floor was a heavy dark fabric pulled taut. Light-proof fabric was pulled taut over the apparatus and around the exterior to eliminate ambient light cues. Two 18” fluorescent lights were positioned at the top and center of each long wall. [For six participants, a single light was positioned at the center of the ceiling. Performance did not differ in the two lighting situations (Mann-Whitney U = 12, P = 0.56).] Four small yellow cups, about 1” tall and 1” in diameter, were inverted and placed in each corner of the room to serve as hiding places for a gaming token. Because participants were deaf, there was no need to suppress ambient sound.

The participant stood in the center of the room while the experimenter drew the participant's attention to a small white plastic gaming token that she then placed under one of the four cups. The participant was then blindfolded and turned around slowly 6–10 times until disoriented (but not dizzy). Disorientation was ensured on every trial by having the participant point to the door without removing the blindfold. Participants had been instructed to point to the door when the experimenter tapped them once on the shoulder. Participants who pointed to an incorrect location were presumed to be disoriented and turned once or twice more to face one of the two long walls (either 90° or 270° from their starting position) before removing the blindfold. Participants who pointed correctly to the location of the door were presumed to be oriented still and were turned several more times, repeating this procedure while still blindfolded until they failed to point correctly to the door. Most participants were easily disoriented on the first attempt. After disorientation, the blindfold was removed, and the participant was asked to point to the location where he or she thought the token was hidden. The experimenter stood behind the participant and looked at the ceiling or floor while the participant searched to avoid biasing the participant's selection.

Rotated Box Condition.

The rotated box condition paralleled the disorientation condition except that (i) the apparatus was an 8“ wide × 12” long × 8” high (0.23 m × 0.30 m × 0.23 m) acrylic black box with one short red side, (ii) the apparatus was rotated, and (iii) the participant remained stationary and oriented. The box was placed with the red side directly across from the participant. Four inverted pink cups were placed in the corners of the box to serve as hiding places for a gaming token. As in the disorientation condition, the experimenter placed the token under a cup in one of the four corners while the participant watched. After blindfolding the participant, the experimenter rotated the box to the preassigned orientation, then tapped the participant to indicate that they could remove the blindfold and search for the token.

Coding.

Two fixed, random orders of eight trials were generated for each condition, with the constraints that the token was hidden in each corner twice, and never in the same corner for two sequential trials. For the trials involving a given corner, participants faced the two long walls once each. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two orders for each condition. For each trial, the participant's first choice of location was recorded and categorized as correct, rotational error, near error, or far error (Fig. 1 C and D). After an incorrect search, the experimenter revealed the correct location.

Familiarization Trials.

In both conditions before the eight test trials, participants received two trials using a small container that had an upper and a lower chamber. The container was placed in the center of the room or box, and the token was hidden in one of the chambers. The same disorientation and search or rotation and search procedures were used in the familiarization trials as in the test trials.

Language Elicitation.

Descriptions of each of the four hiding places were elicited following the eight test trials for both conditions. The language measure for each apparatus was compared with performance on the spatial task using that apparatus. For language elicitation, participants were randomly assigned to one of two fixed random orders. After watching the experimenter hide the token in one of the four corners, participants were moved to a new location where they could not see the apparatus, with their body oriented in a different direction, and videotaped while they described the hiding location “so that another person could find it.”

Videotaped descriptions were coded offline with respect to five aspects of spatial language. (i) Mentioning a ground. Descriptions were coded for whether or not the signer provided information about the ground of the spatial relationship. Specifically, explicit mention of the walls of the disorientation room or the sides of the box were tallied. (ii) Simultaneous mention of figure and ground. Trials that included the simultaneous presentation of figure and ground information were tallied, for example, the articulation of a sign for the token alongside a sign for the wall. (iii) Mentioning the red wall. For each trial, it was noted whether the red wall (the landmark) was mentioned. (iv) Consistency of placement of the red wall. Across the four trials, the proportion of trials articulating a sign for the red wall in a single location was computed. A score was assigned based on the most frequently used location; for example, a signer who used one location three times and another one time would receive a score of 0.75. (v) Consistency in marking left–right relations. Across the four trials, the proportion of trials that mapped left and right consistently was computed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nicaraguan deaf participants, the Melania Morales Center for Special Education, the National Nicaraguan Association of the Deaf (ANSNIC), and the Nicaraguan Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sports (MECD) for their assistance and cooperation, and Quaker House, Managua, for providing testing facilities. We also thank A. del Solar, M. Flaherty, S. Hasbun, and A. Kocab, for research assistance and S. Theran for statistical consultation. This research was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship funded by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) Training Grant 5 T32 DC00041, a Women in Cognitive Science Travel Award, a Wellesley College Dean's Office Grant, and a fellowship from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study (to J.E.P); an National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, a Stimson Restricted Research Award from the Harvard Psychology Department, and a Wesleyan University Project Grant (to A. Shusterman.); National Institutes of Health/NIDCD Grants R01 DC005407 (to A. Senghas), RO1 DC010997 (to K.E.), and NICHD Grant R01 HD23103 (to E.S.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Hermer-Vazquez L, Spelke E-S, Katsnelson A-S. Sources of flexibility in human cognition: Dual-task studies of space and language. Cognit Psychol. 1999;39:3–36. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1998.0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hermer L, Spelke E-S. A geometric process for spatial reorientation in young children. Nature. 1994;370:57–59. doi: 10.1038/370057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowerman M, Choi S. In: Language Acquisition and Conceptual Development. Bowerman M, Levinson S-C, editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 475–511. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levinson S-C. Space in Language and Cognition: Explorations in Cognitive Diversity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majid A, Bowerman M, Kita S, Haun D-B, Levinson S-C. Can language restructure cognition? The case for space. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng K, Newcombe N-S. Is there a geometric module for spatial orientation? Squaring theory and evidence. Psychon Bull Rev. 2005;12:1–23. doi: 10.3758/bf03196346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li P, Gleitman L. Turning the tables: Language and spatial reasoning. Cognition. 2002;83:265–294. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(02)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li P, Abarbanell L, Papafragou A. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Forbus K, Gentner D, Reiger T, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levinson SC, Kita S, Haun D-B, Rasch B-H. Returning the tables: Language affects spatial reasoning. Cognition. 2002;84:155–188. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(02)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kegl J, Senghas A, Coppola M. In: Language Creating and Language Change: Creolization, Diachrony, and Development. DeGraff M, editor. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1999. pp. 179–237. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polich L. The Emergence of the Deaf Community in Nicaragua. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senghas A. In: Proceedings of the 19th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. MacLaughlin D, McEwen S, editors. Vol. 19. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press; 1995. pp. 543–552. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senghas A, Coppola M, Newport EL, Supalla T. In: Proceedings of the 21st Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Hughes E, Hughes M, Greenhill A, editors. Vol. 21. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press; 1997. pp. 550–561. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senghas A, Coppola M. Children creating language: How Nicaraguan sign language acquired a spatial grammar. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:323–328. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senghas A. Intergenerational influence and ontogenetic development in the emergence of spatial grammar in Nicaraguan Sign Language. Cogn Dev. 2003;18:511–531. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senghas A, Kita S, Ozyürek A. Children creating core properties of language: Evidence from an emerging sign language in Nicaragua. Science. 2004;305:1779–1782. doi: 10.1126/science.1100199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermer L, Spelke E. Modularity and development: The case of spatial reorientation. Cognition. 1996;61:195–232. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(96)00714-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermer-Vazquez L, Moffet A, Munkholm P. Language, space, and the development of cognitive flexibility in humans: The case of two spatial memory tasks. Cognition. 2001;79:263–299. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shusterman A, Spelke E. In: The Structure of the Innate Mind. Carruthers P, Laurence S, Stich S, editors. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratliff K-R, Newcombe N-S. Is language necessary for human spatial reorientation? Reconsidering evidence from dual task paradigms. Cognit Psychol. 2008;56:142–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haun D-B-M, Rapold C-J, Call J, Janzen G, Levinson S-C. Cognitive cladistics and cultural override in Hominid spatial cognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17568–17573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607999103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Learmonth A-E, Newcombe N-S, Sheridan N, Jones M. Why size counts: Children's spatial reorientation in large and small enclosures. Dev Sci. 2008;11:414–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hupbach A, Hardt O, Nadel L, Bohbot V-D. Spatial reorientation: Effects of verbal and spatial shadowing. Spat Cogn Comput. 2007;7:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gouteux S, Thinus-Blanc C, Vauclair J. Rhesus monkeys use geometric and nongeometric information during a reorientation task. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2001;130:505–519. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.130.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly D-M, Spetch M-L, Heth C-D. Pigeons’ (Columba livia) encoding of geometric and featural properties of a spatial environment. J Comp Psychol. 1998;112:259–256. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vargas J-P, López J-C, Salas C, Thinus-Blanc C. Encoding of geometric and featural spatial information by goldfish (Carassius auratus) J Comp Psychol. 2004;118:206–216. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.118.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emmorey K. In: Modality and Structure in Signed and Spoken Languages. Meier R-P, Quinto-Pozos D-G, Cormier K-A, editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 405–421. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emmorey K. Perspectives on Classifier Constructions in Sign Languages. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emmorey K, Kosslyn S-M, Bellugi U. Visual imagery and visual-spatial language: Enhanced imagery abilities in deaf and hearing ASL signers. Cognition. 1993;46:139–181. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(93)90017-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emmorey K, Kosslyn S-M. Enhanced image generation abilities in deaf signers: A right hemisphere effect. Brain Cogn. 1996;32:28–44. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1996.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emmorey K, Klima E, Hickok G. Mental rotation within linguistic and non-linguistic domains in users of American sign language. Cognition. 1998;68:221–246. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(98)00054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newcombe N-S, Ratliff K-R. In: The Emerging Spatial Mind. Plumert J-M, Spencer J-P, editors. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spelke E. In: Language in Mind: Advances in the Investigation of Language and Thought. Gentner D, Goldin-Meadow S, editors. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2003. pp. 277–311. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank M-C, Everett D-L, Fedorenko E, Gibson E. Number as a cognitive technology: Evidence from Pirahã language and cognition. Cognition. 2008;108:819–824. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landau B, Dessalegn B, Goldberg A-M. In: Language, Cognition and Space: The State of the Art and New Directions. Chilton P, Evans V, editors. London: Equinox Publishing; [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan G, Herman R, Barriere I, Woll B. The onset and mastery of spatial language in children acquiring British Sign Language. Cogn Dev. 2008;23:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rigal R. Right-left orientation: Development of correct use of right and left terms. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;79:1259–1278. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.79.3.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pyers J-E, Senghas A. Language promotes false-belief understanding: Evidence from learners of a new sign language. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:805–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayberry R. When timing is everything: Age of first-language acquisition effects on second-language learning. Appl Psycholinguist. 2007;28:537–549. [Google Scholar]