Abstract

In the past year, two members of the nuclear receptor family, liver X receptor β (LXRβ) and thyroid hormone receptor α (TRα), have been found to be essential for correct migration of neurons in the developing cortex in mouse embryos. TRα and LXRβ bind to identical response elements on DNA and sometimes regulate the same genes. The reason for the migration defect in the LXRβ−/− mouse and the possibility that TRα may be involved are the subjects of the present study. At E15.5, expression of reelin and VLDLR was similar but expression of apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) (the reelin receptor) was much lower in LXRβ−/− than in WT mice. Knockout of ApoER2 is known to lead to abnormal cortical lamination. Surprisingly, by postnatal day 14 (P14), no morphological abnormalities were detectable in the cortex of LXRβ−/− mice and ApoER2 expression was much stronger than in WT controls. Thus, a postnatal mechanism leads to increase in ApoER2 expression by P14. TRα also regulates ApoER2. In both WT and LXRβ−/− mice, expression of TRα was high at postnatal day 2. By P14 it was reduced to low levels in WT mice but was still abundantly expressed in the cortex of LXRβ−/− mice. Based on the present data we hypothesize that reduction in the level of ApoER2 is the reason for the retarded migration of later-born neurons in LXRβ−/− mice but that as thyroid hormone (TH) increases after birth the neurons do find their correct place in the cortex.

Keywords: apolipoprotein E receptor 2, cerebral cortex, development, embryo

Liver X receptor (LXR) is a subfamily of the nuclear receptor family of transcription factors. The two members of this subfamily are LXRα (1), which plays a key role in cholesterol homeostasis and LXRβ (2), which has irreplaceable functions in the central nervous system (3–6).

We have previously shown that LXRβ regulates brain cholesterol levels and that LXRβ expression is essential for maintenance of motor neurons in the spinal cord and dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, suggesting that there are important roles for LXR action in brain development and, possibly, also in neurological disease (7, 8). LXRβ is widely expressed in mouse brain at later embryonic stages and is localized in the upper layers of the cerebral cortex in normal postnatal mice (9). Our analysis of brain development in LXRβ−/− mice revealed smaller brain size, which was caused by a reduction in the number of neurons in superficial cortical layers (9). Mammalian corticogenesis involves layering of neurons in an “inside-out” fashion, with earliest generated neurons positioned in the deepest layers and later generated neurons migrating beyond previously established layers to adopt progressively more superficial levels (9, 10). This process is essential for cortical structure and establishment of correct neural connections. We have shown that the defect in cortical development in LXRβ−/− mice is a direct consequence of an inability of later-born neurons to migrate to superficial layers and that this, in turn, is a consequence of abnormalities in vertical processes of radial glial cells along which migrating neurons travel (9). Thus, LXRβ plays a specific role in cortex lamination and is essential for radial migration of later-generated neocortical neurons in embryonic mice.

Cortical abnormalities observed with LXRβ−/− mice are strikingly similar to defects produced by mutations of apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) (11), originally termed the LDL receptor-related protein CD91 (12). ApoER2 and its ligand reelin are essential for migration of developing cortical neurons to find their place in the correct layer of the cortex (11, 13). Reelin is normal in LXRβ−/− mice (9), but the fact that there are defects in neuronal migration in the cortex raises the question of whether there may be defects in ApoER2.

Many members of the nuclear hormone receptor family play important roles in brain development. Thyroid hormone (TH) regulates brain development and hypothyroidism can lead to mental retardation, anxiety, and even psychosis (14, 15). TH signaling is mediated by two closely related thyroid hormone receptors (TRs), with the TRα subtype strongly expressed in the brain (16). Like LXRs, the TRs are mostly localized in nuclei and associate with DNA in the presence and absence of their cognate ligand. TH, whose circulating levels increase sharply after birth, regulates gene expression by altering receptor conformation and changing the complement of coregulators that are recruited to TR on promoters of target genes (17–19). Recent evidence suggests that TRs can also relocate to the cytoplasm, where they may trigger rapid second messenger signaling events (20). The role of cytoplasmic TRs is not clear.

LXRs bind to the same response element on DNA as TRs and sometimes regulate the same genes (21–23). The defects in cholesterol homeostasis seen in the livers of LXRα−/− mice are not compensated for by TRs (24), but interactions of LXRs and TRs in the CNS have not been investigated.

In the present study, we have analyzed the architecture of the cerebral cortex in embryonic and neonatal LXRβ−/− mice. Remarkably, morphological abnormalities of the cortex seen at E15.5 are normalized between postnatal day 2 (P2) and postnatal day 14 (P14). We now present evidence for the role of ApoER2 and TR in the abnormalities and reparation of the defects and propose that TRα compensates for the lack of LXRβ in cortical development.

Results

Abnormal Cortical Layers in LXRβ−/− Mice at a Late Embryonic Stage and Early Postnatal Stages.

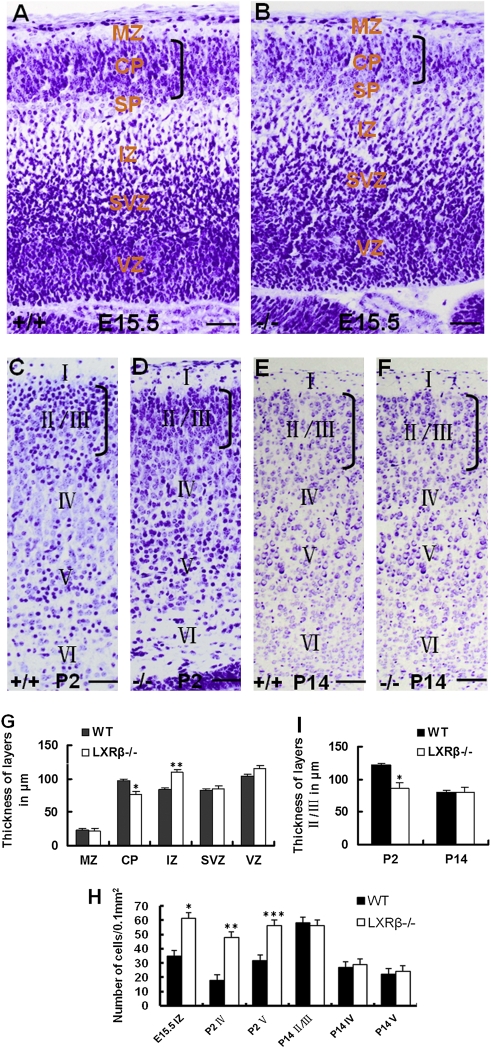

The laminated structure of the cerebral cortex was examined at later embryonic and early postnatal stages and a comparison was made between LXRβ−/− mice and WT controls with cresyl violet Nissl staining. At E15.5, the cortical plate (CP) appeared thinner in the LXRβ−/− mice than in WT controls, whereas the intermediate zone (IZ) was thicker in the mutant mice than in WT controls (Fig. 1 A, B, and G). There was no overall difference in the appearance or thickness of the marginal zone (MZ), subventricular zone (SVZ), or ventricular zone (VZ). However, the density of neurons occupying the IZ of LXRβ−/− mice was higher than in WT controls (Fig. 1 A, B, and H). This indicates that migration of many neurons was arrested at the IZ.

Fig. 1.

Morphological alteration of embryonic and early postnatal cortex in LXRβ−/− mice. (A–I) Sagittal sections of the E15.5 neocortex and coronal sections of P2 and P14 stained with cresyl violet. (A and B) At E15.5, the CP is thinner and density of neurons in the IZ is higher in LXRβ−/− mice (B) than in WT controls (A). (C and D) At P2, the layers II/III in LXRβ−/− mice (D) are thinner than in WT controls (C) and the neuronal density in layers IV and V of LXRβ−/− mice (D) is higher than that of WT controls (C). (E and F) No overall morphological difference can be observed in the cortex in LXRβ−/− mice (F) compared with WT controls (E) at P14. (A–F) There is no visible difference in the MZ, SVZ, and VZ at E15.5 (A and B) and layer I at P2 (C and D) or P14 (E and F) between WT and LXRβ−/− mice. (G and I) The thickness of cortical layers at E15.5 (G) (*P = 0.002 for CP; **P = 0.012 for IZ of LXRβ−/− mice compared with WT controls, by Student's t test), and the thickness of layers II/III at P2 and P14 (I) (*P = 0.01 at P2 for LXRβ−/− mice compared with WT controls). (H) The density of cells/0.1 mm2. In LXRβ−/− mouse brain, there is a significant increase in the IZ at E15.5 (*P = 0.001), layer IV (**P = 0.032), and V (***P = 0.008) at P2. All of the results were expressed as mean ± SD. Three brains were used for each genotype. (Scale bars: A–F, 50 μm.)

To determine the consequences of the halt in neuronal migration during embryogenesis on newborn mice, the cortex was examined at an early (P2) and a later postnatal stage (P14). At P2, the layers II/III occupied by the later-born neurons was thinner in LXRβ−/− mice and the neuronal density in layers IV and V was greater than that of WT controls (Fig. 1 C, D, H, and I). Surprisingly, however, no overall morphological differences in the cortex were observed between WT and LXRβ−/− mice at P14 (Fig. 1 E, F, H, and I). There were no visible differences in layer I (Fig. 1 C and D) and the hippocampus at P2 (Fig. S1 A and B) or P14 (Fig. S1 C and D) between WT and LXRβ−/− mice. Thus, the early defects in cerebral cortex architecture are corrected in the postnatal period.

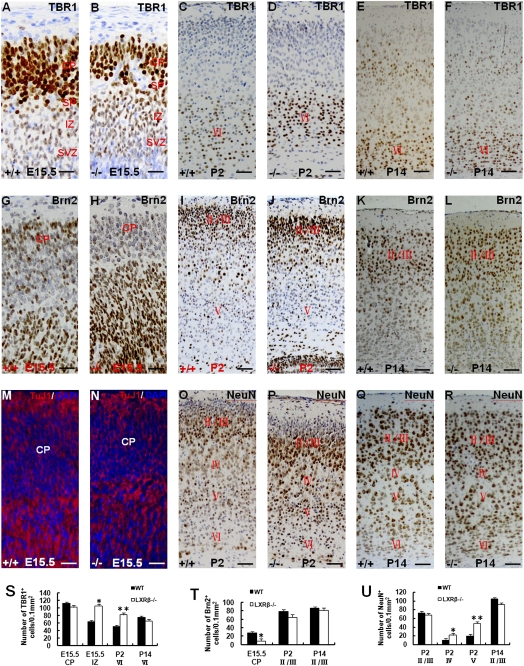

Important Role of LXRβ for Early and Later-Generated Neuronal Migration.

To know which stage of neuronal migration was influenced by LXRβ, the transcription factors T box brain 1 (TBR1) and Brn2 were used as early-generated and later-generated neuronal labels, respectively (9, 10). At E15.5, TBR1 was highly expressed at the lower CP. Lower levels were observed at the IZ/SVZ, and it was not detectable in the VZ (Fig. 2 A and B). More TBR1-positive neurons were located at IZ in LXRβ−/− mice than WT controls (Fig. 2 A, B, and S). No statistical difference for TBR1-positive neuronal density was observed in the CP between LXRβ−/− mice and WT controls at E15.5 (Fig. 2 A, B, and S). A few focal CP dysplasias were observed in LXRβ−/− mice at E15.5 (Fig.2 B), but at P2 (Fig. 2 C and D) and P14 (Fig. 2 E and F) the focal CP dysplasias were no longer present. At P2 in the LXRβ−/− mouse brain, the density of TBR1-positive neurons in layer VI was higher than that in WT mice (Fig. 2 C, D, and S). No such difference was detectable at P14 (Fig. 2 E, F, and S). At E15.5, there were fewer Brn2-positive neurons located in the superficial CP of LXRβ−/− mouse brain than in the WT controls (Fig. 2 G, H, and T). These differences indicate that the later-generated neurons migrate to the superficial CP to form the future layers IV, III, and II according to the right “inside-out” sequence in WT controls (9) but that in LXRβ−/− mice, Brn2-positive neurons could not migrate to the superficial CP. At P2, there was no difference between WT and LXRβ−/− mice in the density of Brn2-positive neurons in layers II/III measured as cells/0.1 mm2 (Fig. 2 I, J, and T). However, the total number of Brn2-positive neurons in layers II/III of LXRβ−/− mice was lower than in WT controls because this layer was thinner in LXRβ−/− mice (Fig. 2 I and J). At P14 there was no visible difference between LXRβ−/− mice and WT controls in the thickness of the Brn2-positive layers II/III and density of Brn2-positive neurons in layers II/III (Fig. 2 K, L, and T) underscoring the idea that there is full recovery of cortical architecture between P2 and P14.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of cortical layer markers TBR1 and Brn2 and neuronal specific markers. (A and B) TBR1 is located at the CP and IZ/SVZ, especially at the lower CP, but is absent in the VZ in WT controls (A) and LXRβ−/− mice (B) at E15.5. (B) A few focal CP dysplasias can be found in LXRβ−/− mice. (A–F) In the LXRβ−/− mouse brain, there is a significant increase in TBR1-positive neuronal density in the IZ at E15.5 (B) and in layer VI at P2 (D) compared with WT controls (A and C), but there is no difference at P14 (E and F). (G–L) Brn2-positive neurons locating in the superficial CP at E15.5 (H) and layers II/III at P2 (J) of LXRβ−/− mouse brain are fewer than in WT controls (G and I), but there is no difference at P14 (K and L). (M and N) TuJ1 staining shows that there are fewer positive neurons in the CP in LXRβ−/− mice (N) than in WT controls (M) at E15.5. (O and P) Most of the NeuN-positive neurons are located in the lower part of layers II/III at P2 but more NeuN-positive neurons stay at the layers IV and V in LXRβ−/− mice (P) than in WT controls (O). (Q and R) NeuN staining shows no overall difference between LXRβ−/− and WT cortex at P14. (S) The density of TBR1-positive cells in the CP and IZ at E15.5 (n = 3; *P = 0.004 for LXRβ−/− mice compared with WT controls) and layer VI at P2 (n = 3; **P = 0.006 for LXRβ−/− mice compared with WT controls) and P14 is shown. (T) The density of Brn2-positive neurons in the CP at E15.5 and layers II/III at P2 and P14 (n = 3; *, P = 0.007 for LXRβ−/− mice compared with WT controls). (U) The density of NeuN-positive neurons in cortical layers at P2 and P14. In the LXRβ−/− mouse brain there is a significant increase in NeuN-positive neuronal density in the layers IV and V at P2 (n = 3; *P = 0.008; **P = 0.001). (Scale bars: A, B, G, H, M, N, 100 μm; C–F, I–L, O–R, 50 μm.)

Immunohistochemical staining with Neuron-specific class III beta-tubulin (TuJ1), a marker of immature neurons and Neuronal Nuclei (NeuN), a marker of postmitotic neurons, were used in this study (25). TuJ1 immunofluorescent staining showed fewer positive neurons in the CP in LXRβ−/− mice than WT controls at E15.5 (Fig. 2 M and N). At P2, most of the NeuN-positive neurons were located at the lower parts of layers II/III but more neurons remained at the layers IV and V in the LXRβ−/− mice than the WT controls (Fig. 2 O, P, and U). Many immature neurons occupying the superficial parts of layers II/III at P2 were NeuN-negative (Fig. 2 O and P), and these neurons became mature at P14 in LXRβ−/− mouse cortex and WT controls (Fig. 2 Q and R) so that there was no visible difference in NeuN distribution at P14 between LXRβ−/− mouse cortex and WT controls (Fig. 2 Q, R, and U).

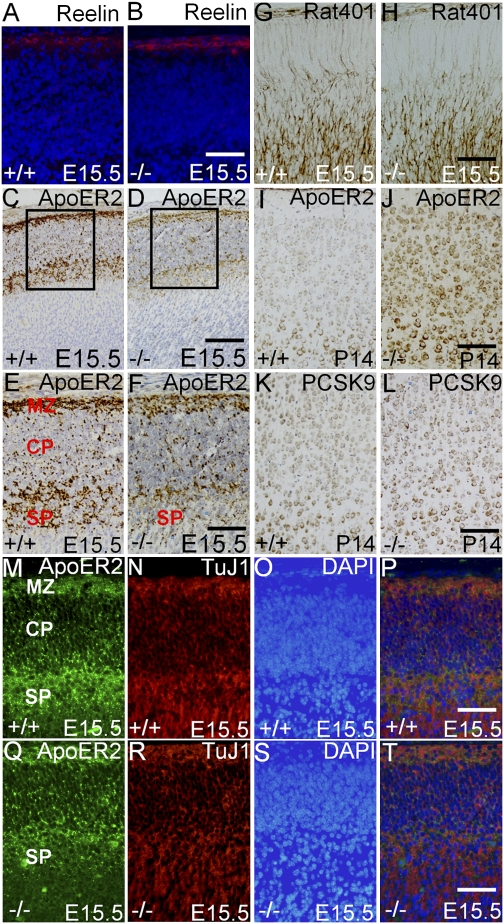

Abnormal Expression of ApoER2 and Abnormal Scaffold of Radial Glia Fibers in E15.5 Neocortex of LXRβ−/− Mice.

There was no visible difference in the reelin expression in MZ between WT and LXRβ−/− mice at E15.5 (Fig. 3 A and B). Therefore, we examined whether the abnormalities observed could be caused by a defect in the reelin receptors, ApoER2 and VLDLR (26). In the WT mouse cortex at E15.5, ApoER2 was distributed mostly in the MZ, lower CP, and subplate (SP) (Fig. 3 C, E, and M). However, in the LXRβ−/− mouse brain there was remarkably weak staining in the SP (Fig. 3 D, F, and Q). ApoER2 was expressed on the neuronal projections and membrane at the embryonic stage (Fig. 3 M–T) and only on the neuronal membrane and cytoplasm at P14 (Fig. 3 I and J). At P2, the ApoER2 staining was not detectable, but at P14, ApoER2 expression in LXRβ−/− mice was very strong, whereas it was barely detectable in layers II/III in WT controls (Fig. 3 I and J).

Fig. 3.

Abnormal expression of ApoER2 and abnormal scaffold of radial glia fibers in E15.5 neocortex of LXRβ−/− mice. (A and B) There is no visible difference in the reelin expression (Red) in the MZ between WT and LXRβ−/− mice at E15.5. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Blue). (C, E, and M) ApoER2 is distributed mostly in the MZ, lower CP and SP in WT controls at E15.5. (D, F, and Q) ApoER2 is decreased sharply in the SP in LXRβ−/− mouse brain. (E and F) Higher-power views of the boxed areas in C and D. (I, J, and M–T) ApoER2 is expressed on neuronal projections and membrane during E15.5 (M–T) but only expressed on the neuronal membrane and cytoplasm at P14 (I and J). (I–L) The expression of ApoER2 (J) and PCSK9 (L) appears stronger in LXRβ−/− mouse brain than in WT controls (I and K) at P14. (G and H) The scaffold of radial glial fibers is more intact and more processes are distributed in the CP in WT controls (G) than in LXRβ−/− mice (H) at E15.5. (Scale bars: A, B, and E–T, 100 μm; C, D, 50 μm.)

To examine whether higher expression of ApoER2 in the LXRβ−/− mouse brain at P14 is due to a difference in degradation of the protein, we examined expression of the protein normally involved in its degradation, i.e., PSCK9 (27). Immunohistochemical staining with a PCSK9 antibody showed no staining at E15.5, but at P14 expression of PSCK9 in LXRβ−/− mice was stronger than in WT controls (Fig. 3 K and L), indicating that decreased degradation by PCSK9 is not responsible for the accumulation of ApoER2 in the LXRβ−/− mouse brain in the postnatal period.

At E15.5, the scaffolds of radial glial fibers, detected with antibodies against Rat401 (28) in WT controls, were more intact and more processes were distributed throughout the CP than in LXRβ−/− mouse cortex (Fig. 3 G and H). VLDLR, a stop signal for neuronal migration, was examined, but there was no staining at E15.5 or P2.

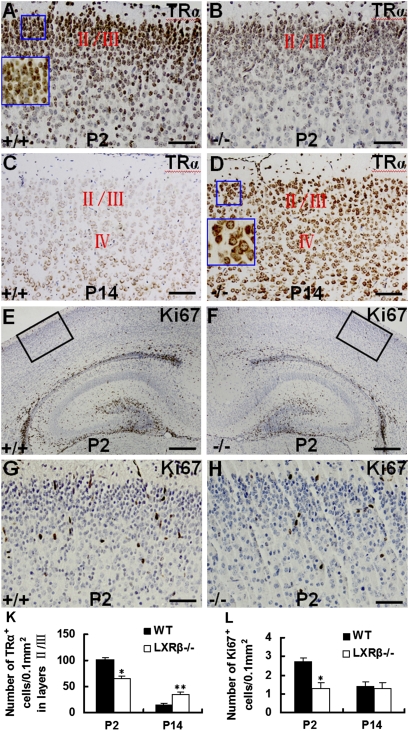

Up-Regulation of Thyroid Hormone Receptor α.

The focal CP dysplasia in LXRβ−/− mice observed at E15.5 disappeared after birth, and no morphological differences in the cortex could be discerned at P14 between WT and LXRβ−/− mice regarding the Nissl and layer-marker staining. Thus, some mechanism must compensate for the absence of LXRβ in the time between P2 and P14. Because LXRs and TRs sometimes regulate similar genes, we tested the possibility that alterations in TR signaling pathways could play a compensatory role and repair the neuronal deficit caused by loss of LXRβ (21–23). At P2, there was strong nuclear staining for TRα in layers II/III (Fig. 4 A and B) and the density of TRα-positive cells in WT controls was higher than in LXRβ−/− mice at P2 (Fig. 4 K). However, at P14, there were far more TRα-positive cells distributed throughout the LXRβ−/− mouse cortex than in the WT controls (Fig.4 C, D and K). In contrast to P2, however, almost all of the TRα-positive cells at day 14 exhibited cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 4 A and D Insets). TRα is implicated in neuroblast proliferation (29) so we tested the possibility that TRα-dependent proliferation accounts for recovery of cortical morphology. Ki67 is a proliferation marker that is expressed by proliferating cells in all phases of the active cell cycle (G1, S, G2, and M phase) but not in resting (G0) cells (30). At P2, more proliferation was observed in the WT control cortex than in the LXRβ−/− mice (Fig. 4 E–H and L). At P14 no difference in Ki67 expression was detectable between LXRβ−/− mice and WT controls. Thus, changes in TRα expression and subcellular localization are not related to changes in cortical neuronal proliferation.

Fig. 4.

Expression of TRα and proliferation in LXRβ−/− mouse cortex. (A and B) At P2, layers II/III are occupied by TRα-positive cells and all of the cells have nuclear staining in WT controls (A) and LXRβ−/− mice (B). (C and D) By contrast, at P14, TRα-positive cells distributing throughout the LXRβ−/− mouse cortex (D) are far more abundant than in WT controls (C). (A and D Insets) Higher magnification image of area in box; note strictly nuclear staining in A Inset and cytoplasmic staining in B Inset. (E–H) At P2, more Ki67-positive cells are observed in the WT control cortex (E and G) than in LXRβ−/− mice (F and H). (G and H) Higher-power views of the boxed areas in E and F. (K) The density of TRα-positive cells in layers II/III in LXRβ−/− mice at P2 (n = 3; *P = 0.002 compared with WT controls) and P14 (n = 3; **P = 0.005 compared with WT controls). (L) The density of Ki67-positive cells in the cortex at P2 and P14. In the LXRβ−/− mouse cortex the Ki67-positive neuronal density is less than in WT controls at P2 (n = 3; *P = 0.016) but no difference is seen at P14. (Scale bars: A–D, G, and H, 100 μm; E and F, 50 μm.)

Discussion

LXRβ is expressed ubiquitously in the brain and appears in the neurons as early as E14.5 (9). Knockout of LXRβ gives rise to abnormal cortex lamination because of the retardation in the migration of later-born neurons. The inability to migrate appears to be due to truncation of the vertical processes of radial glia (9) upon which the migrating neurons depend for their direction.

In the present study, we demonstrate that in LXRβ−/− mice, the cortical development is aberrant at later embryonic and early postnatal stage but recovers at later postnatal stages. At E15.5, the cortical plate was thinner in LXRβ−/− mice brains than in WT mice and there was an accumulation of neurons at the IZ. At P2, the cortex developed from the cortical plate was still thinner in LXRβ−/− mice with fewer neurons in layers II/III and in contrast, more neurons at layers IV and V. Surprisingly however, the cortex appeared normal by P14. This normalization suggested that those neurons that were arrested at layers IV and V at P2 in LXRβ−/− mice migrated to the superficial layers later. Although loss of LXRβ arrested cortical neuronal migration, the lamination and morphology of the hippocampus were normal at P2 and P14.

Analysis of early and late-born neuronal markers supports the idea that there is an early deficit in neuronal migration in LXRβ−/− mice but that the brain compensates for this deficit between P2 and P14. At E15.5, there were fewer TBR1-positive neurons (early-born neurons) (9, 10) in CP in LXRβ−/− mice, although the cell density was not different. However in the IZ, as was evident with Nissl staining, there were more TBR1-positive neurons in LXRβ−/− mice than in WT controls. At P14, no differences in the distribution of TBR1-positive neurons were observed between WT and LXRβ−/− mice. In addition, there were a few focal cortical plate dysplasias in LXRβ−/− mice at E15.5, but none were detectable after birth. These results suggest that some neurons recovered the ability to migrate after birth. Brn2 is a marker of later-born neurons destined to superficial CP to form the future cortical layers II/III (9, 10). At E15.5 and P2, there were fewer Brn2-positive neurons in CP in the LXRβ−/− mice than in WT controls. However, at P14 there were no differences in the number or location of Brn2-positive neurons between WT and LXRβ−/− mice. Clearly, as described previously (9), migration of later-born neurons was arrested when LXRβ was not expressed but some mechanism compensated for this deficit between P2 and P14.

Immunofluorescent staining showed that at E15.5, there were fewer TuJ1-positive neurons (25) in the CP of the LXRβ−/− mice. This is consistent with the Nissl and TBR1 staining results. At P2, most of the NeuN-positive neurons in WT mice were located at the lower parts of layers II/III but more neurons remained in the layers IV and V in the LXRβ−/− mice than in the WT controls. Almost all of the superficial neurons in layers II/III of LXRβ−/− mice were NeuN-negative indicating that these neurons were latest-born and immature. No difference of NeuN-positive (mature neurons) staining was observed between LXRβ−/− mice and WT controls at P14. Thus the immature neurons located in the superficial layers in both mouse lines at P2 became mature at P14, and by this time, the abnormalities in LXRβ−/− mice had normalized.

We propose that the deficit in neuronal migration in LXRβ−/− mice is related to reduced expression of ApoER2, the reelin receptor. Reelin has functions in the developing brain (31–35). In cortical development, reelin is crucial for correct positioning of radially migrating neuronal precursors via its binding to ApoER2 and VLDLR on neuronal precursors (11, 36, 37). In ApoER2 mutants, many later-born neurons fail to migrate to their destinations in superficial cortical layers, and some neurons invade the marginal zone in VLDLR mutants (10). Thus, the two reelin receptors, VLDLR and ApoER2, play divergent roles, with VLDLR mediating a stop signal for migrating neurons and ApoER2 as an essential signal for the migration of later-born neurons (10). In the present study, we did not find any abnormalities of the number of Cajal-Retzius neurons nor the intensity of their immunostaining for reelin in LXRβ−/− mice (9). However, expression of ApoER2 was different in LXRβ−/− mice. Later-born neurons destined to superficial cortical layers strongly express both LXRβ (9) and ApoER2 (10), suggesting that ApoER2 may be regulated by LXRβ. In the WT mouse cortex at E15.5, ApoER2 was distributed mostly in the MZ, lower CP, and subplate (SP) (10). In the LXRβ−/− mouse brain, there was weak staining for ApoER2 in the SP. Costaining of TuJ1 and ApoER2 showed that ApoER2 was expressed more strongly on the neuronal projections and membrane during embryonic development.

At P14, ApoER2 expression in LXRβ−/− mice was very strong in layers II/III, whereas it was barely detectable in WT controls. Therefore, ApoER2 appears to have a different regulation mode and role during the embryonic and postnatal stages. To examine whether the higher expression of ApoER2 in the LXRβ−/− brain at P14 is due to a difference in degradation of the protein, the enzyme—PSCK9—responsible for degradation of ApoER2 (27, 38, 39) was examined. Immunohistochemical staining for PCSK9 showed that decreased degradation was not a likely cause for the accumulation of ApoER2 at P14.

LXRs bind to the same response element on DNA as does TR and regulates many of the same genes (21–23). Although TR does not compensate for the function of LXRs in LXR knockout mice in cholesterol homeostasis (24), it is possible that TR can compensate for some of the defects due to loss of LXRβ in the CNS. TRα plays a key role in postnatal development where it presumably mediates most of the thyroid hormone effects. TRβ is detected in few areas of the brain (16, 40, 41). We found strong nuclear staining for TRα in WT and LXRβ−/− mice at P2. However, at P14, there were far more TRα-positive cells distributed throughout the LXRβ−/− mouse cortex than in the WT controls. This finding raises the possibility that increased expression of TRα may compensate for loss of LXRβ and stimulate the retarded neurons to migrate to their correct position. It is noteworthy that almost all of the TRα staining was cytoplasmic at P14. This is in marked contrast to P2, where TRα was strictly nuclear. From Ki67 staining, it appears that there was no increase in neuronal proliferation in the postnatal period in LXRβ−/− mice. Therefore, a role of TR in normalizing the cortex is in migration, not in proliferation.

We suggest that there may be two possible effects of TRα on LXR signaling in cortical development. First, unliganded TRs suppress gene transcription. Thus, migration of TRα from a nuclear to cytoplasmic location could derepress ApoER2 gene expression by removing inhibitory influences at possible TRE/LXRE elements (42). Alternatively, plasma levels of TH increase sharply during neonatal and postnatal periods (42–44) and in the presence of its ligand, TR leaves the nucleus and is cytoplasmic. Cytoplasmic TR may modulate cell behavior and gene expression by triggering second messenger pathways (17–19).

We conclude that reduction in the level of ApoER2 is the likely reason for the retarded migration of later born neurons in LXRβ−/− embryonic mice but that postnatal changes in TR signaling pathways permit neurons to find their correct place in the cortex (45).

Materials and Methods

The generation of LXRβ−/− mice has been described (3). Heterozygous mice were used for breeding. The day of vaginal plug detection was designated as E0.5. Embryonic and P2 and P14 mice brains were obtained as described in SI Materials and Methods. Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining were performed as previously described (7, 9). Detailed procedures are described in SI Materials and Methods. For layer thickness measuring and cell counting, MicroSuite Basic Edition and Image Pro Plus 6.0 were used, respectively. The number of mice in each experiment was at least three per genotype. Data are presented as mean ± SD. The statistical significance of differences between LXRβ−/− and control samples was assessed by using Student's t test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Swedish Science Council and the European Integrated Project on Nuclear Receptors, Chemicals as contaminants in the food chain: an NoE for research, risk assessment and education (CASCADE).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1006162107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Apfel R, et al. A novel orphan receptor specific for a subset of thyroid hormone-responsive elements and its interaction with the retinoid/thyroid hormone receptor subfamily. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7025–7035. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.7025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teboul M, et al. OR-1, a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that interacts with the 9-cis-retinoic acid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2096–2100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberti S, et al. Hepatic cholesterol metabolism and resistance to dietary cholesterol in LXRbeta-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:565–573. doi: 10.1172/JCI9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson KM, et al. The liver X receptor-β is essential for maintaining cholesterol homeostasis in the testis. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2519–2530. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steffensen KR, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling; a panel of mouse tissues discloses novel biological functions of liver X receptors in adrenals. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33:609–622. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, et al. Liver X receptors in the central nervous system: From lipid homeostasis to neuronal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13878–13883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172510899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HJ, et al. Liver X receptor beta (LXRbeta): A link between beta-sitosterol and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-Parkinson's dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2094–2099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711599105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson S, Gustafsson N, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Inactivation of liver X receptor beta leads to adult-onset motor neuron degeneration in male mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3857–3862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500634102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan X, Kim HJ, Bouton D, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Expression of liver X receptor beta is essential for formation of superficial cortical layers and migration of later-born neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13445–13450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806974105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hack I, et al. Divergent roles of ApoER2 and Vldlr in the migration of cortical neurons. Development. 2007;134:3883–3891. doi: 10.1242/dev.005447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trommsdorff M, et al. Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2. Cell. 1999;97:689–701. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stöhr J, Schindler G, Rothe G, Schmitz G. Enhanced upregulation of the Fc gamma receptor IIIa (CD16a) during in vitro differentiation of ApoE4/4 monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1424–1432. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.9.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert de Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM. The reeler mouse as a model of brain development. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1998;150:1–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zamoner A, Heimfarth L, Pessoa-Pureur R. Congenital hypothyroidism is associated with intermediate filament misregulation, glutamate transporters down-regulation and MAPK activation in developing rat brain. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:1092–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nayak B, Hodak SP. Hyperthyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:617–656. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.06.002. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley DJ, Young WS, 3rd, Weinberger C. Differential expression of alpha and beta thyroid hormone receptor genes in rat brain and pituitary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7250–7254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yen PM, Wilcox EC, Hayashi Y, Refetoff S, Chin WW. Studies on the repression of basal transcription (silencing) by artificial and natural human thyroid hormone receptor-beta mutants. Endocrinology. 1995;136:2845–2851. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.7.7789309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda H, Paul BD, Choi CY, Shi YB. Contrasting effects of two alternative splicing forms of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 on thyroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription in Xenopus laevis. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1082–1094. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul BD, Fu L, Buchholz DR, Shi YB. Coactivator recruitment is essential for liganded thyroid hormone receptor to initiate amphibian metamorphosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5712–5724. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5712-5724.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guigon CJ, Cheng SY. Novel non-genomic signaling of thyroid hormone receptors in thyroid carcinogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;308:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enmark E, Gustafsson JA. Comparing nuclear receptors in worms, flies and humans. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:611–615. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01859-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berkenstam A, Färnegårdh M, Gustafsson JA. Convergence of lipid homeostasis through liver X and thyroid hormone receptors. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:707–717. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quack M, Frank C, Carlberg C. Differential nuclear receptor signalling from DR4-type response elements. J Cell Biochem. 2002;86:601–612. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peet DJ, Janowski BA, Mangelsdorf DJ. The LXRs: A new class of oxysterol receptors. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:571–575. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kornack DR, Rakic P. Cell proliferation without neurogenesis in adult primate neocortex. Science. 2001;294:2127–2130. doi: 10.1126/science.1065467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Z. Molecular regulation of neuronal migration during neocortical development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;42:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirier S, et al. The proprotein convertase PCSK9 induces the degradation of low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and its closest family members VLDLR and ApoER2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2363–2372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen GD, Sherman GF, Galaburda AM. Radial glia in the neocortex of adult rats: Effects of neonatal brain injury. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1994;82:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lezoualc'h F, et al. Inhibition of neurogenic precursor proliferation by antisense alpha thyroid hormone receptor oligonucleotides. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12100–12108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerdes J, et al. Immunobiochemical and molecular biologic characterization of the cell proliferation-associated nuclear antigen that is defined by monoclonal antibody Ki-67. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:867–873. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrade N, et al. ApoER2/VLDL receptor and Dab1 in the rostral migratory stream function in postnatal neuronal migration independently of Reelin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8508–8513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611391104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dulabon L, et al. Reelin binds alpha3beta1 integrin and inhibits neuronal migration. Neuron. 2000;27:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilmore EC, Herrup K. Cortical development: Receiving reelin. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R162–R166. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heins N, et al. Glial cells generate neurons: The role of the transcription factor Pax6. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:308–315. doi: 10.1038/nn828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanada K, Gupta A, Tsai LH. Disabled-1-regulated adhesion of migrating neurons to radial glial fiber contributes to neuronal positioning during early corticogenesis. Neuron. 2004;42:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D'Arcangelo G, et al. Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors. Neuron. 1999;24:471–479. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hiesberger T, et al. Direct binding of Reelin to VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of disabled-1 and modulates tau phosphorylation. Neuron. 1999;24:481–489. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maxwell KN, Breslow JL. Adenoviral-mediated expression of Pcsk9 in mice results in a low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7100–7105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402133101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rashid S, et al. Decreased plasma cholesterol and hypersensitivity to statins in mice lacking Pcsk9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5374–5379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501652102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivas M, Naranjo JR. Thyroid hormones, learning and memory. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6(Suppl 1):40–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mellström B, Naranjo JR, Santos A, Gonzalez AM, Bernal J. Independent expression of the alpha and beta c-erbA genes in developing rat brain. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1339–1350. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-9-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pathak A, Sinha RA, Mohan V, Mitra K, Godbole MM. Maternal thyroid hormone before the onset of fetal thyroid function regulates reelin and downstream signaling cascade affecting neocortical neuronal migration. Cereb Cortex. 2010 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq052. 10.1093/cercor/bhq052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernal J, Guadaño-Ferraz A, Morte B. Perspectives in the study of thyroid hormone action on brain development and function. Thyroid. 2003;13:1005–1012. doi: 10.1089/105072503770867174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porterfield SP, Hendrich CE. The role of thyroid hormones in prenatal and neonatal neurological development—current perspectives. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:94–106. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-1-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams GR. Neurodevelopmental and neurophysiological actions of thyroid hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:784–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.