Abstract

Predominantly hydrophobic unnatural nucleotides that selectively pair within duplex DNA as well as during polymerase-mediated replication have recently received much attention as the cornerstone of efforts to expand the genetic alphabet. We recently reported the results of a screen and subsequent lead hit optimization that led to the identification of the unnatural base pair formed between the nucleotides dMMO2 and d5SICS. This unnatural base pair is replicated by the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I with better efficiency and fidelity than other candidates reported in the literature. However, its replication remains significantly less efficient than a natural base pair, and further optimization is necessary for its practical use. To better understand and optimize the slowest step of replication of the unnatural base pair, the insertion of dMMO2 opposite d5SICS, we synthesized two dMMO2 derivatives, d5FM and dNaM, which differ from the parent nucleobase in terms of shape, hydrophobicity, and polarizability. We find that both derivatives are inserted opposite d5SICS more efficiently than dMMO2 and that overall the corresponding unnatural base pairs are generally replicated with higher efficiency and fidelity than the pair between dMMO2 and d5SICS. In fact, in the case of the dNaM and d5SICS heteropair, the efficiency of each individual step of replication approaches that of a natural base pair, and the minimum overall fidelity ranges from 103 to 104. In addition, the data allow us to propose a generalized model of unnatural base pair replication, which should aid in the further optimization of the unnatural base pair, and possibly in the design of additional unnatural base pairs that are replicated with truly natural-like efficiency and fidelity.

1. Introduction

The development of an unnatural base pair to supplement the natural base pairs, dA:dT and dG:dC, would increase the biotechnological utility of DNA and is the first, and likely most challenging, step towards expansion of the genetic code and the creation of a semi-synthetic organism. Such efforts were pioneered in the Benner lab through the design of nucleotides with unnatural hydrogen-bonding (H-bonding) topologies.1–5 More recent work from our lab6–13 and the Hirao lab14–18 has built upon the remarkable observations from the Kool lab19–21 that H-bonds are not required for base pair replication and has focused on the pairing of nucleotides bearing predominantly hydrophobic nucleobases. These efforts have relied on rational design and structure-activity relationships,22–27 and have yielded several unnatural base pair candidates that are replicated surprisingly well considering their unnatural structures.11,18,24 However, none of the candidates are replicated with the efficiency and fidelity of the natural base pairs. In addition, the effect of sequence on the replication of the candidate unnatural base pairs remains largely unexplored, and while small variations are expected, any realistic unnatural base pair candidate must be shown to be replicated efficiently and accurately regardless of sequence context.

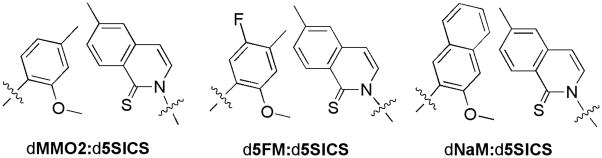

Efforts based on rational design have helped to elucidate the determinants of stability and efficient replication of DNA, but they are limited by our incomplete understanding of the forces involved. As an alternative to rational design, we recently screened a pool of 3,600 predominantly hydrophobic base pair candidates to identify those that are most efficiently replicated by the exonuclease deficient Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA Pol I (Kf).10 Initial optimization of the most promising lead yielded the heteropair formed between dMMO2 and d5SICS (Figure 1), which is well recognized not only by Kf,10 but also by a variety of other DNA polymerases.12 In the sequence context examined, Kf synthesizes the d5SICS:dMMO2 heteropair (where dY:dX denotes the strand context with dY in the primer and dX in the template) with a second order rate constant (kcat/KM, or efficiency) that is only 7-fold smaller than that of natural synthesis, but then continues primer extension by incorporation of the next correct dNTP with a rate that is 250-fold slower than extension of a natural base pair. Synthesis of the heteropair in the opposite strand context (i.e. dMMO2:d5SICS) is the rate limiting step of replication, proceeding nearly 1,000-fold slower than synthesis of a natural base pair, while extension is more efficient, occurring only 90-fold slower than extension of a natural base pair. Thus, although the unnatural base pair formed between d5SICS and dMMO2 is replicated more efficiently than those identified previously by rational design, neither the efficiency nor the fidelity of its replication approaches that of natural synthesis, and further optimization is still required.

Figure 1.

Unnatural base pairs used in this study. Only the nucleobase analogs are depicted with the sugar and phosphates omitted for clarity.

Structure-activity relationship studies with both dMMO2 and d5SICS revealed that the substituents ortho to the glycosidic linkage, i.e. the methoxy group of dMMO2 and the sulfur atom of d5SICS, are essential for polymerase recognition.10,11,13 These substituents likely act as H-bond acceptors in the developing minor groove where they are required to engage polymerase-based H-bond donors.28–31 In contrast, substituents positioned meta or para to the glycosidic linkage, which are expected to be disposed in the developing major groove, do not appear to directly engage the polymerase, and their effect on heteropair replication is more variable. Thus, the meta and para positions of dMMO2 and d5SICS appear to be best suited for derivatizations aimed at improving replication.

Here, we report our efforts to optimize the heteropair by meta and para derivatization of dMMO2, whose incorporation into DNA is the slowest step of replication. We characterized the effects of a fluorine substituent at the meta position (d5FM, Figure 1) and increased aromatic surface area associated with ring fusion at the meta, para positions (dNaM, Figure 1). To more fully understand the generality of the unnatural base pairs, we fully characterized replication in two different sequence contexts. We find that both d5FMTP and dNaMTP are inserted opposite d5SICS with significantly greater efficiency than dMMO2TP, and moreover, we find that neither modification significantly interferes with any other step of replication. In fact, in the two sequence contexts examined, each individual step of replication of the heteropair formed between dNaM and d5SICS is within 8- to 140-fold and 6- to 490-fold, respectively, of a natural base pair, and overall fidelity ranges from 103 to 104. Thus, the efficiency and fidelity of the heteropair’s replication by Kf are beginning to approach those of natural synthesis and are likely sufficient for in vitro applications,32–40 and possibly for the initiation of in vivo efforts, as well.41 In addition, the data allow us to propose a unified model of unnatural base pair replication in which intrastrand intercalation plays a central role, and which should prove invaluable for the further optimization of these and other unnatural base pairs.

2. Results

The unnatural nucleotides d5FM and dNaM were designed to explore the effects of altered nucleobase polarity and surface area and were synthesized as described in the Supporting Information. Both nucleotides were converted to the corresponding triphosphate or phosphoramidite, and each phosphoramidite was incorporated into primer and template oligonucleotides via automated DNA synthesis. Heteropair synthesis is gauged by determining the second order rate constant (kcat/KM) for insertion of an unnatural triphosphate opposite an unnatural nucleotide in the template under steady state conditions;42 extension is gauged by determining kcat/KM for insertion of the next correct dNTP. Fidelities are calculated as the ratio of second order rate constants for synthesis or extension of the correct unnatural base pair to that for a mispair. Each heteropair and mispair is fully characterized in both possible strand contexts (i.e. dY:dX and dX:dY) and the minimum overall fidelity is determined as the product of the minimum single step fidelities.

To evaluate the generality of the results, the replication (synthesis and extension) of the heteropairs was characterized in two sequence contexts. Sequence context I is the same as that used previously to characterize a wide variety of unnatural base pairs,6–13,22–24,43–46 including the original analysis of the heteropair formed between dMMO2 and d5SICS,10 and in this context the unnatural nucleotide in the template is flanked by a 3′ dT and a 5′ dG. In sequence context II, the natural nucleotides are inverted so that the unnatural nucleotide is flanked by a 3′ dG and a 5′ dT. Sequence contexts III and IV are the same as context I, except the 3′ nucleotide that flanks the unnatural base in the template is a dA or a dC, respectively.

2.1 Unnatural heteropair replication in sequence context I

2.1.1 Synthesis and extension with d5SICS in the template

We first examined the Kf-mediated insertion of d5FMTP and dNaMTP opposite d5SICS in sequence context I. For reference, the insertion of dMMO2TP opposite d5SICS, which is the step that most limits the replication of the parental heteropair in this sequence context, proceeds with a second order rate constant of 3.6 × 105 M−1min−1 (Table 1). The moderately efficient insertion of dGTP results in a minimum synthesis fidelity of only 3 for correct dMMO2:d5SICS heteropair synthesis in this sequence context. Characterization of the derivative base pairs in sequence context I revealed that Kf inserts d5FMTP and dNaMTP opposite d5SICS with efficiencies that are 10- and 14-fold higher than that for dMMO2TP, respectively (Table 1). Thus, the rate of the slowest step of heteropair synthesis is increased from 888-fold slower than natural synthesis in the case of dMMO2, to only 88- or 64-fold slower for d5FM and dNaM, respectively. Correspondingly, the minimum synthesis fidelity is increased from only 3, for the synthesis of the dMMO2:d5SICS pair, to 28 for d5FM:d5SICS and 38 for dNaM:d5SICS.

Table 1.

Second-order rate constants (kcat/KM values) for heteropair and mispair synthesis and extension with d5SICS in the template (context I)a

| 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA(Y) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCTCT(X)GCTAGGTTACGGCAGGATCGC | |||

| X | Y | Synthesis (M−1min−1) | Extension (M−1min−1) |

| T | A | (3.2 ± 0.6) × 108b | (1.7 ± 02) × 108b |

| 5SICS | MMO2 | (3.6 ± 0.7) × 105 | (1.9 ± 0.2) × 106 |

| 5FM | (3.6 ± 0.4) × 106 | (5.5 ± 0.9) × 106 | |

| NaM | (5.0 ± 0.1) × 106 | (1.2 ± 0.4) × 106 | |

| 5SICS | (2.7 ± 0.9) × 104c | <1.0 × 103c | |

| A | (2.2 ± 0.3) × 104c | 1.0 × 104c | |

| G | (1.3 ± 0.8) × 105c | (4.9 ± 0.5) × 103c | |

| C | <1.0 × 103c | 4.2 × 103c | |

| T | (1.3 ± 0.4) × 104c | (4.0 ± 0.2) × 105c | |

Perhaps the most remarkable attribute of the parental heteropair formed between dMMO2 and d5SICS, relative to other unnatural base pairs that have been investigated, is its relatively efficient extension in both possible strand contexts. For dMMO2:d5SICS in sequence context I, the efficiency of extension is 1.9 × 106 M−1 min−1, which is only 90-fold lower than a natural base pair.10 The most efficiently extended mispair in this strand and sequence context is dT:d5SICS, which limits the minimum fidelity for correct heteropair extension to 5 (Table 1). However, since the synthesis of dT:d5SICS is not efficient, its impact on replication fidelity is minimized. As with dMMO2:d5SICS, extension of d5FM:d5SICS and dNaM:d5SICS is also very efficient in this sequence context (Table 1), resulting in minimum extension fidelities of 14 and 3, respectively. Thus, both of the derivatizations improve synthesis without interfering with extension, and when the effects on both steps are combined, these modifications increase the minimum overall replication fidelity from 130 for dMMO2:d5SICS, to 3,800 and 1,260 for d5FM:d5SICS and dNaM:d5SICS, respectively.

2.1.2 Synthesis and extension with dMMO2, d5FM, or dNaM in the template

We next investigated whether the derivatization of dMMO2 affects the efficiency or fidelity of replication in the opposite strand context (Table 2). For reference, with dMMO2 in the template, Kf inserts d5SICSTP with an efficiency of 4.7 × 107 M−1 min−1, and while it does not insert dGTP, dCTP, or dTTP, it does insert dATP and dMMO2TP, albeit 470- and 390-fold slower than d5SICSTP, respectively. Kf inserts d5SICSTP slightly less efficiently with d5FM in the template than with dMMO2 in the template; however, at 1.4 × 107 M−1 min−1, the efficiency remains high. Kf does not insert dGTP, dCTP, or dTTP opposite d5FM; however, it does insert d5FMTP with moderate efficiency, and dATP only slightly less efficiently, which results in the reduced minimum synthesis fidelity of 16 for d5SICS:d5FM. Problematically, the dA:d5FM mispair is also extended with moderate efficiency (see below), and this ultimately limits the overall fidelity of the d5FM-based heteropair in this strand and sequence context.

Table 2.

Second-order rate constants (kcat/KM values) for heteropair and mispair synthesis and extension with dMMO2 or a derivative in the template (context I).a

| 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA(Y) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCTCT(X)GCTAGGTTACGGCAGGATCGC | |||

| X | Y | Synthesis (M−1min−1) | Extension (M−1min−1) |

| MMO2 | 5SICS | (4.7 ± 0.4) × 107b | (6.7 ± 1.1) × 105b |

| MMO2 | (1.2 ± 0.1) × 105c | (5.3 ± 0.9) × 103c | |

| A | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 105c | (4.6 ± 0.2) × 104c | |

| G | <1.0 × 103c | <1.0 × 103c | |

| C | <1.0 × 103c | (1.2 ± 0.5) × 106c | |

| T | <1.0 × 103c | (6.6 ± 0.2) × 105c | |

| 5FM | 5SICS | (1.4 ± 0.2) × 107 | (2.3 ± 0.2) × 106 |

| 5FM | (8.9 ± 0.7) × 105 | (2.6 ± 0.8) × 104 | |

| A | (3.0 ± 0.5) × 105 | (3.2 ± 0.4) × 105 | |

| G | <1.0 × 103 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| C | <1.0 × 103 | (2.0 ± 0.4) × 106 | |

| T | (2.4 ± 0.9) × 103 | (2.0 ± 0.2) × 106 | |

| NaM | 5SICS | (3.7 ± 0.4) × 107 | (2.7 ± 0.2) × 106 |

| NaM | (3.4 ± 0.8) × 106 | (1.1 ± 0.3) × 104 | |

| A | (7.1 ± 2.9) × 105 | (3.9 ± 1.8) × 104 | |

| G | <1.0 × 103 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| C | <1.0 × 103 | (1.5 ± 0.1) × 106 | |

| T | (5.6± 0.5) × 103 | (5.7 ± 0.3) × 105 | |

With dNaM in the template, the insertion of d5SICSTP is very efficient, in fact, slightly more efficient than with d5FM in the template, and only 8-fold less efficient than insertion of dATP opposite dT (Table 2). Neither dGTP nor dCTP is inserted opposite dNaM, but dTTP and dATP are inserted slightly more efficiently than they are opposite d5FM, and dNaMTP is inserted opposite itself with an efficiency of 3.4 × 106 M−1 min−1, which limits the minimum synthesis fidelity of the d5SICS:dNaM heteropair in this sequence context to 11. However, the relatively inefficient extension of these mispairs minimizes their impact on overall fidelity (see below).

Relative to its synthesis, extension of the d5SICS:dMMO2 heteropair in sequence context I is somewhat less efficient (kcat/KM = 6.7 × 105 M−1 min−1, 254-fold lower than natural synthesis, Table 2), and this is the second most limiting step in the replication of the parental heteropair. Characterization of mispair extension (Table 2) revealed that the dG:dMMO2 mispair is not efficiently extended, while the mispair with dA is extended more efficiently (kcat/KM = 4.6 × 104 M−1 min−1), and the mispairs with dT and dC are extended as fast and actually 2-fold faster than the parental heteropair d5SICS:dMMO2. The extension of the dT and dC mispairs is efficient; however, because neither is synthesized at a detectable rate they do not compromise replication. The fidelity of the parental heteropair replication in this strand and sequence context is ~7,000.

By comparison with d5SICS:dMMO2, extension of the d5SICS:d5FM heteropair is significantly more efficient (kcat/KM = 4.1 × 106 M−1 min−1); however, the mispairs with d5FM in the template are also generally extended more efficiently than those with dMMO2 in the template (Table 2). Extension of the dC:d5FM and dT:d5FM mispairs is virtually as efficient as that for the correct d5SICS:d5FM heteropair, but as with dMMO2 in the template, neither the dC:d5FM nor the dT:d5FM mispair is efficiently synthesized (see above). However, the dA:d5FM mispair is also extended more efficiently than the dA:dMMO2 mispair, and along with its moderately efficient synthesis (see above), the mispair with dA limits the overall fidelity of the d5SICS:d5FM heteropair in this sequence context to slightly greater than 300. Thus, fluorine substitution significantly reduces the fidelity of heteropair replication in this strand and sequence context.

As with d5FM, the d5SICS:dNaM heteropair is extended more efficiently than the parental d5SICS:dMMO2 heteropair; however, in this case none of the mispairs are extended more efficiently than the corresponding mispairs with dMMO2 in the template (Table 2). While the minimum extension fidelity is only 2, d5SICS:dNaM is the first heteropair that is selectively extended in this strand context relative to all possible mispairs. Moreover, only the mispairs with dA and dNaM are synthesized and extended with any efficiency, and it is these mispairs that ultimately limit the fidelity of replication, but in this case, the minimum fidelity remains high at 3 × 103. Thus, compared to the parental heteropair, the increased aromatic surface area of dNaM significantly improves the fidelity of dNaM:d5SICS replication without significantly reducing it in the opposite strand context.

2.2 Unnatural heteropair replication in sequence context II

2.2.1 Synthesis and extension with d5SICS in the template

To determine whether the improvements in heteropair replication are general, we next fully characterized the different heteropairs and mispairs in sequence context II. For reference, the synthesis and extension of a natural dA:dT base pair in sequence context II is virtually the same as in sequence context I (Table 3). The insertion of dMMO2 opposite d5SICS proceeds with an efficiency of 4.8 × 105 M−1 min−1 (Table 3), and when compared with the efficiencies of mispair synthesis, this results in a minimum fidelity for correct heteropair synthesis of 2.

Table 3.

Second-order rate constants (kcat/KM values) for heteropair and mispair synthesis and extension with d5SICS in the template (context II).a

| 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGC(Y) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCTCG(X)TCTAGGTTACGGCAGGATCGC | |||

| X | Y | Synthesis (M−1min−1) | Extension (M−1min−1) |

| T | A | (3.3 ± 0.1) × 108 | (3.1 ± 0.4) × 108 |

| 5SICS | MMO2 | (4.8 ± 1.8) × 105 | (3.2 ± 0.1) × 105 |

| 5FM | (4.2 ± 0.8) × 106 | (1.3 ± 0.6) × 106 | |

| NaM | (4.1 ± 0.1) × 107 | (6.8 ± 2.2) × 105 | |

| 5SICS | (2.4 ± 0.2) × 105 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| A | (5.9 ± 0.8) × 104 | (3.6 ± 1.6) × 103 | |

| G | (1.9 ± 0.5) × 105 | <1.0 × 103b | |

| C | <1.0 × 103 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| T | (8.5 ± 1.1) × 103 | (3.3 ± 0.2) × 105 | |

See Experimental Section for details.

As in sequence context I, insertion of d5FMTP and dNaMTP opposite d5SICS in sequence context II is significantly more efficient than insertion of dMMO2TP (Table 3). In fact, for dNaMTP, the relative increase in efficiency is significantly greater in sequence context II than it is in sequence context I. These increases in efficiency result in d5FM:d5SICS and dNaM:d5ICS heteropairs that are synthesized only 79- and, remarkably, only 8-fold less efficiently, respectively, than a natural base pair. When compared with the rates of mispair synthesis (Table 3), this results in a minimum synthesis fidelity of 18 and 170, respectively, for the d5FM:d5SICS and dNaM:d5SICS heteropairs.

As observed in sequence context I, the extension of dNaM and d5FM paired opposite d5SICS in the template of sequence context II is slightly more efficient than with dMMO2 paired opposite d5SICS (Table 3). While the extension efficiencies of the heteropairs in this strand context are slightly lower in sequence context II than in sequence context I, this is also generally the case for the mispairs. The only mispair with d5SICS in sequence context II that is extended with any efficiency is that with dT (kcat/KM = 3.3 × 105 M−1 min−1). Extension of dT:d5SICS is as efficient as extension of dMMO2:d5SICS, but 2- to 4-fold less efficient than extension of d5FM:d5SICS or dNaM:d5SICS. Although the synthesis of dT:d5SICS is only marginally efficient (see above), extension of this mispair is sufficiently efficient that it limits the minimum overall replication fidelity of the heteropair. Nonetheless, the overall fidelity of this step is increased from 53 for dMMO2:d5SICS, to 1,800 for d5FM:d5SICS, and, remarkably, to 10,000 for dNaM:d5SICS.

2.2.2 Synthesis and extension with dMMO2, d5FM, or dNaM in the template

Synthesis of the parental heteropair by insertion of d5SICSTP opposite dMMO2 proceeds with an efficiency of 6.6 × 107 M−1 min−1 in sequence context II (Table 4). d5SICSTP is also inserted opposite d5FM and dNaM in sequence context II with remarkable efficiency (8.0 × 107 M−1 min−1 and 5.5 × 107 M−1 min−1, respectively). The dA:dMMO2 mispair and the dMMO2:dMMO2 self pair are synthesized nearly 20-fold more efficiently than in sequence context I, and these mispairs limit the minimum synthesis fidelity of the parental heteropair to 36, and the d5SICS:d5FM and d5SICS:dNaM heteropairs to 26 and 12, respectively. This slight reduction in synthesis fidelity does not compromise overall fidelity, as in each case the most efficiently synthesized mispairs are extended much less efficiently than the correct heteropairs (see below).

Table 4.

Second-order rate constants (kcat/KM values) for heteropair and mispair synthesis and extension with dMMO2 or a derivative in the template (context II).a

| 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGC(Y) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3′-ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCTCG(X)TCTAGGTTACGGCAGGATCGC | |||

| X | Y | Synthesis (M−1min−1) | Extension (M−1min−1) |

| MMO2 | 5SICS | (6.6 ± 0.5) × 107 | (1.7 ± 0.8) × 106 |

| MMO2 | (1.8 ± 1.2) × 106 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| A | (1.7 ± 0.3) × 106 | (1.1 ± 0.3) × 104 | |

| G | (7.9 ± 2.1) × 103 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| C | (3.0 ± 0.8) × 103 | (4.4 ± 1.0) × 105 | |

| T | (5.2 ± 2.7) × 103 | (2.0 ± 0.6) × 106 | |

| 5NaM | 5SICS | (5.5 ± 0.7) × 107 | (4.1 ± 0.1) × 106 |

| 5NaM | (4.8 ± 1.2) × 106 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| A | (1.4 ± 0.4) × 106 | (1.4 ± 0.1) × 104 | |

| G | (3.7 ± 0.4) × 103 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| C | (6.4 ± 2.6) × 103 | (3.0 ± 0.7) × 105 | |

| T | (8.3 ± 1.4) × 103 | (8.3 ± 0.6) × 105 | |

| 5FM | 5SICS | (8.0 ± 0.8) × 107 | (8.2 ± 0.3) × 106 |

| 5FM | (2.7 ± 0.6) × 106 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| A | (3.1 ± 0.1) × 106 | (4.4 ± 0.1) × 104 | |

| G | (1.2 ± 0.4) × 103 | <1.0 × 103 | |

| C | (7.5 ± 0.6) × 103 | (1.5 ± 0.4) × 106 | |

| T | (1.2 ± 0.6) × 104 | (4.1 ± 1.0) × 106 | |

See Experimental Section for details.

Once synthesized, the d5SICS:dMMO2, d5SICS:d5FM, and d5SICS:dNaM heteropairs are all extended with high efficiency (Table 4), but as with each of the mispairs, these efficiencies are somewhat lower than those observed in sequence context I. The mispairs with dT are consistently the most efficiently extended, but because they are not efficiently synthesized, they do not compromise the minimum overall fidelity. For each heteropair in this strand and sequence context, the minimum overall fidelity is limited by mispairing with dA. The dMMO2- and d5FM-based heteropairs have a minimum overall fidelity of 6,100 and 4,700, respectively, while the dNaM-based heteropair has a remarkable minimum overall fidelity of 12,100.

2.3 Synthesis of dNaM:d5SICS in sequence contexts III and IV

Virtually without exception, both unnatural and natural triphosphates are inserted opposite unnatural nucleobases in the template more efficiently in sequence context II than in context I. The difference is most pronounced for the insertion of dNaMTP, which is almost 10-fold faster in sequence context II than in context I. To further probe this sequence dependence, we examined two additional sequence contexts, III and IV, which differ from sequence context I only at the position immediately 3′ to the unnatural nucleotide in the template. In the four sequence contexts I–IV, the natural base pair in the primer-template preceding the unnatural nucleotide is dA:dT, dC:dG, dT:dA, and dG:dC, respectively. Insertion of dNaMTP opposite d5SICS proceeds with an efficiency of 5.9 × 106 M−1 min−1 in sequence context III and 6.8 × 107 M−1 min−1 in sequence context IV. Thus, the rate of unnatural base pair synthesis is nearly identical in contexts I and III, as well as in contexts II and IV, suggesting that the identity, but not the strand context of the flanking natural base pair is important for unnatural triphosphate insertion.

3. Discussion

The unnatural base pair formed between d5SICS and dMMO2 was identified by optimizing the most promising lead from a screen of 3,600 candidates. While the heteropair formed between dMMO2 and d5SICS is replicated better than the unnatural base pairs we have examined previously, its replication still requires further optimization to approach that of a natural base pair. Toward this goal we synthesized and characterized the dMMO2 analogs d5FM and dNaM. These derivatives differ from dMMO2 in nucleobase dipole moment, shape, aromatic surface area, and hydrophobicity, which have all been shown to significantly impact unnatural base pair replication.7,13,24,41,45 The modifications are made at the positions meta and para to the glycosidic linkage, which have been shown to be tolerant of modification.10

Unnatural heteropair replication and its sequence-dependence

Insertion of dMMO2 opposite d5SICS limits the synthesis of the parental heteropair in both sequence contexts characterized. We find that the efficiency of this step of replication is significantly increased by both the fluorine substituent of d5FM (by ~10-fold) and by the increased aromatic surface area of dNaM (by 14- to 85-fold, depending on sequence context). In the opposite strand context, dMMO2, d5FM, and dNaM all template the insertion of d5SICSTP with similarly high efficiency. Both the fluorine substituent and the increased aromatic surface area also generally increase the rate of natural dNTP insertion, with the exception of dGTP in context II, where the rate of mispair synthesis is decreased 6- and 2-fold, respectively. Both unnatural pair and mispair synthesis were consistently more efficient in sequence context II than I. In addition, the efficiency of dNaMTP insertion opposite d5SICS is the same in sequence contexts I and III as well as in contexts II and IV. These data suggest that the observed sequence dependencies reflect the nature of the natural base pair that precedes the unnatural base pair being synthesized, with a dG:dC or a dC:dG resulting in similar and relatively more efficient insertion than a dA:dT or dT:dA, which also resulted in similar efficiencies. Thus, we conclude that the identity of the flanking base pair is important, while its strand context is not.

The d5FM:d5SICS and d5SICS:d5FM heteropairs are extended 3- to 6-fold more efficiently than the parental heteropair between dMMO2 and d5SICS, while the dNaM:d5SICS heteropair is extended with an efficiency similar to the parental heteropair in the same sequence context, and the d5SICS:dNaM heteropair is extended 2- to 4-fold more efficiently. Relative to dMMO2, the mispairs with a natural nucleotide in the primer paired opposite d5FM are also generally extended slightly faster while those with dNaM are not. As with heteropair and mispair synthesis, we also observe a sequence dependence on the rate of mispair extension, which is generally more efficient in sequence context I than in context II. The only exceptions are with dMMO2, d5FM, or dNaM in the template where the pairs with d5SICS or dT are extended slightly more efficiently in context I. While extension in the two sequence contexts involves the insertion of a different natural triphosphate, dCTP in context I and dATP in context II, this difference is unlikely to be the origin of the observed differences in extension efficiency as the rate of natural base pair extension is identical in the two sequence contexts.

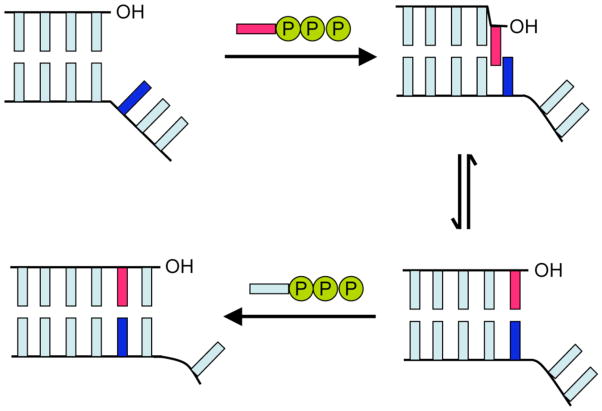

A model for unnatural base pair replication

Previously, we proposed a model of unnatural base pair extension wherein pairs formed between analogs with large aromatic nucleobases are difficult to extend due to an intercalative mode of pairing that results in distortions of the primer terminus.9 We thus attribute the generally less efficient heteropair and mispair extension in sequence context II to increased intercalation of the primer terminus nucleobase in presence of a flanking dC:dG pair, which stacks more favorably in DNA than a dA:dT base pair.47–49 This effect is more pronounced with d5SICS in the template, due to its aromatic surface area that is suitably disposed to pack with the nucleobase of the incoming dNTP. The effect is less pronounced with dMMO2 and d5FM in the template, due to reduced surface area, with dNaM in the template, due to geometrical constraints that preclude packing, and with dT in the primer, possibly due to a reduced ability to intercalate. Thus, in general the primer terminus may be sufficiently flexible to allow some distortion, provided that templating base is incapable of mediating edge-on interactions and sufficiently stabilizing packing interactions are available via intercalation.

Unlike for extension, data collected previously has not led to the development of a model for unnatural base pair synthesis, but the systematic characterization of unnatural pair and mispair synthesis reported here provides more insight. The observed sequence dependencies must result from the identity of the natural nucleotide in the template 3′ to the unnatural nucleotide, and possibly with its pairing nucleotide in the primer (the 5′ nucleotide is isolated by a sharp turn in the template and packing interactions with the polymerase). Thus, we infer that the 3′ dG in the template, and/or its pairing dC in the primer of sequence context II favors natural and unnatural dNTP insertion opposite an unnatural nucleotide, relative to the dA:dT base pair of sequence context I. The rates of dNaM:d5SICS synthesis in sequence contexts III and IV support this conclusion and further suggest that the rates depend on the flanking base pair but not on its strand context (i.e. which nucleotide is in the primer strand and which is in the template strand).

The data prompt us to conclude that the intercalative model of base pair extension is also applicable to unnatural base pair and mispair synthesis (Figure 2). Indeed, at least with Kf, an intercalative mode of interaction, both during and after synthesis may dominate when the templating nucleobase is incapable of edge-on interactions but does allow for stable intercalation. This model suggests that efficient replication of predominantly hydrophobic unnatural base pairs requires nucleobase intercalation that is sufficient to facilitate synthesis, but not so stabilizing as to inhibit de-intercalation and continued extension. If further experiments support this model, it should prove invaluable for the continued optimization of the unnatural base pair and perhaps for the design of additional unnatural base pair candidates as well.

Figure 2.

Model for unnatural base pair replication. The unnatural nucleobase in the template is shown in dark blue and the natural or unnatural nucleobase of the incoming dNTP is shown in red.

Efforts to expand the genetic alphabet

From a practical perspective, there are two important and related criteria for the evaluation of any unnatural base pair’s replication: the overall efficiency and fidelity of its replication. The overall efficiency with which the parental heteropair formed between d5SICS and dMMO2 is replicated is limited by the relatively inefficient synthesis of dMMO2:d5SICS and, to a lesser degree, by the extension of d5SICS:dMMO2 (sequence context I), or by the synthesis and extension of dMMO2:d5SICS (sequence context II). The fidelity of heteropair synthesis is most limited by the self pairs or mispairs with purines, while the fidelity of extension is limited by the mispairs with pyrimidines (Table V). Despite their inefficient synthesis, the mispairs with dT most limit overall replication fidelity with d5SICS in the template, and despite their relatively inefficient extension, the mispairs with dA most limit the overall fidelity with dMMO2 in the template. Overall, these mispairs limit the fidelity of d5SICS:dMMO2 to between 6,000 and 7,000, and dMMO2:d5SICS to 53 and 130 in sequence contexts I and II, respectively (Table V).

Table 5.

Minimum single step and overall replication fidelitiesa

| Primer | Template | Minimum Synthesis Fidelity | Minimum Extension Fidelity | Minimum Replication Fidelityb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context I | Context II | Context I | Context II | Context I | Context II | ||

| d5SICS | dMMO2 | 390 (dMMO2, dA) | 36 (dMMO2, dA) | 0.6 (dC) | 0.9 (dT) | 6,730 (dA) | 6,100 (dA) |

| dMMO2 | d5SICS | 2.8 (dG) | 2.0 (d5SICS, dG) | 4.8 (dT) | 0.9 (dT) | 130 (dT) | 53 (dT) |

| d5SICS | d5FM | 16 (d5FM) | 26 (dA, d5FM) | 1.2 (dT) | 2.0 (dT) | 330 (dA) | 4,700 (dA) |

| d5FM | d5SICS | 28 (dG) | 18 (d5SICS) | 14 (dT) | 3.9 (dT) | 3,800 (dT) | 1,800 (dT) |

| d5SICS | dNaM | 11 (dNaM) | 12 (dNaM) | 2.7 (dC) | 4.9 (dT) | 2670 (dNaM) | 12,100 (dA) |

| dNaM | d5SICS | 38 (dG) | 170 (dNaM) | 3.0 (dT) | 2.1 (dT) | 1,260 (dT) | 10,000 (dT) |

See text for details. The mispairs that most limit fidelity are indicated in parentheses.

Minimum replication fidelity id the product of synthesis and extension fidelity.

The derivatization of the dMMO2 scaffold with a meta fluorine atom or meta, para-linked aromatic surface area increases by one- to two-orders of magnitude the efficiency of the step that most limits replication, the insertion of the triphosphate opposite d5SICS in the template, due to both an increased kcat and a decreased KM. Along with smaller effects on the other steps of replication, this results in overall fidelities that are, in general, significantly increased relative to the parental heteropair. With d5FM in the primer strand and d5SICS in the template strand, the fidelity increases to almost 4,000-fold in context I, and only slightly less in context II. However, while the overall fidelity remains high with d5SICS in the primer and d5FM in the template in sequence context II (5,000-fold), it is lower in context I (300-fold). The moderate fidelity in context I results from the relatively efficient insertion and extension of the dA:d5FM mispair.

Both the efficiency and the overall fidelity of the heteropair formed between dNaM and d5SICS is remarkable in all strand and sequence contexts examined; the efficiency of every step of replication is within 8- to 140-fold and 6- to 490-fold of a natural base pair in the two sequence contexts examined, and the overall fidelities range from 103 to 104. The fidelities are by far the highest reported for any unnatural base pair and result, at least in part, from the consistent orthogonality of the mispairs that are most efficiently synthesized and those that are most efficiently extended. The high efficiencies and fidelities associated with the heteropair formed between dNaM and d5SICS appear to be generally independent of sequence, are beginning to rival those of natural synthesis, and are likely to be sufficient for most in vitro applications of an expanded genetic alphabet. Given these remarkable properties, we also believe that the heteropair is sufficiently promising to initiate in vivo efforts as part of the long term goal to expand the genetic code and create a semi-synthetic organism. Such efforts are now underway.

4. Experimental Section

General Methods

All reactions were carried out in oven-dried glassware under inert atmosphere and all solvents were dried over 4 Å molecular sieves with the exceptions of dichloromethane, which was distilled from CaH2, and tetrahydrofuran, which was distilled from sodium and potassium metal. All other reagents were purchased from Aldrich. 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker DRX-600, Bruker DRX-500, Varian Inova-400, or Bruker AMX-400 spectrometers. High resolution mass spectroscopic data were obtained from the facilities at The Scripps Research Institute. Polynucleotide kinase was purchased from New England Biolabs, Kf from GE Healthcare, and [γ-32P]-ATP from MP Biomedicals.

Nucleoside synthesis

The synthesis of d5SICS was described previously10 and the synthesis of d5FM and dNaM are described in detail in the Supporting Information. Briefly, for dNaM, 2-methoxy naphthalene was lithiated and coupled to 2-Deoxy-3, 5-O-(tetraisopropyldisiloxane-1, 3-diyl)-D-erythropentofranose. The resulting diol was cyclized under Mitsunobu conditions and deprotection yielded the free nucleoside. For d5FM, 4-fluoro-3-methyl anisole was iodinated with AgNO3 and I2 and then coupled to tert-butyl ((3-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)-2,3-dihydrofuran-2-yl) methoxy) dimethylsilane. In each case anomeric mixtures of nucleosides were obtained and the a anomer was purified by column chromatography and confirmed by NOE and HOMO-COZY NMR spectroscopy (Supporting Information).

Oligonucleotide Synthesis

Oligonucleotides were prepared by the β-cyanoethylphosphoramidite method on controlled pore glass supports (1 μmol) using an Applied Biosystems Inc. 392 DNA/RNA synthesizer. After automated synthesis, the oligonucleotides were cleaved from the support and deprotected by heating in aqueous ammonia solution at 55 °C for 12 h. The crude product was further purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by electroelution. The resulting purified oligonucleotides were precipitated in 80% ethanol and dried overnight. Oligonucleotides were characterized by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Applied Biosystems Voyager DE-PRO System 6008), and their concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically using standard extinction coefficients for the natural nucleotides and extinction coefficients at 260 nm of 1.9 × 10−2, 1.5 × 10−3, and 4.1 × 10−3 M−1m−1 at for d5SICS, d5FM, and dNaM, respectively.

Gel-Based Kinetic Assay

Primer oligonucleotides were 5′ radiolabeled with 32P-ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. Template and primers were annealed in Kf reaction buffer by heating to 90 °C followed by slow cooling to ambient temperature. Assay conditions included 40 nM primer/template, 0.1–1.2 nM Kf, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 50 μg/mL acetylated BSA. The reactions were carried out under steady-state conditions by combining the DNA-enzyme mixture with an equal volume (5 μL) of 2× dNTP stock solution, with varying concentrations of unnatural triphosphate (1 to 2000 μM), and incubating at 25 °C for 1–10 min, and quenching by the addition of 20 μL of loading dye (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, and sufficient amounts of bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol). The reaction mixture was then analyzed by 15% polyacrylamide and 8 M urea denaturing gel electrophoresis. Radioactivity was quantified using a Phosphorimager and the ImageQuant program (Molecular Dynamics) with overnight exposures. The kobs values were plotted against triphosphate concentration and used to fit the Michaelis-Menten equation (Kaleidagraph, Synergy Software). The data presented are averages and standard deviations of three independent determinations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM060005 to F. E. R.) and Korea Research Foundation (KRF-2006-352-C00047 to Y. J. S.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Nucleoside and nucleotide synthesis and characterization.

Complete kinetic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Switzer C, Moroney SE, Benner SA. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:8322–8323. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geyer CR, Battersby TR, Benner SA. Structure (Camb) 2003;11:1485–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moser MJ, Marshall DJ, Greineri JK, Kieffer CD, Killeen AA, Ptacin JL, Richmond CS, Roesch EB, Scherrer CW, Sherrill CB, Van Hout CZ, Zanton SJ, Prudent JR. Clin Chem. 2003;49:407–414. doi: 10.1373/49.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prudent JR. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2006;6:245–252. doi: 10.1586/14737159.6.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Z, Sismour AM, Sheng P, Puskar NL, Benner SA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4238–4249. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa AK, Wu Y, Berger M, Schultz PG, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:8803–8804. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henry AA, Yu C, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9638–9646. doi: 10.1021/ja035398o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leconte AM, Matsuda S, Hwang GT, Romesberg FE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4326–4329. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuda S, Fillo JD, Henry AA, Rai P, Wilkens SJ, Dwyer TJ, Geierstanger BH, Wemmer DE, Schultz PG, Spraggon G, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10466–10473. doi: 10.1021/ja072276d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leconte AM, Hwang GT, Matsuda S, Capek P, Hari Y, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2336–2343. doi: 10.1021/ja078223d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuda S, Leconte AM, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5551–5558. doi: 10.1021/ja068282b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang GT, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14872–14882. doi: 10.1021/ja803833h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu C, Henry AA, Romesberg FE, Schultz PG. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:3841–3844. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021018)41:20<3841::AID-ANIE3841>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitsui T, Kitamura A, Kimoto M, To T, Sato A, Hirao I, Yokoyama S. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5298–5307. doi: 10.1021/ja028806h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirao I. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:622–627. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirao I, Ohtsuki T, Fujiwara T, Mitsui T, Yokogawa T, Okuni T, Nakayama H, Takio K, Yabuki T, Kigawa T, Kodama K, Yokogawa T, Nishikawa K, Yokoyama S. Nat Methods. 2006;3:729–735. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirao I, Mitsui T, Kimoto M, Yokoyama S. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15549–15555. doi: 10.1021/ja073830m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirao I, Harada Y, Kimoto M, Mitsui T, Fujiwara T, Yokoyama S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13298–13305. doi: 10.1021/ja047201d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matray TJ, Kool ET. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:6191–6192. doi: 10.1021/ja9803310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matray TJ, Kool ET. Nature. 1999;399:704–708. doi: 10.1038/21453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morales JC, Kool ET. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12979–12988. doi: 10.1021/bi001578o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMinn DL, Ogawa AK, Wu Y, Liu J, Schultz PG, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11585–11586. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuda S, Henry AA, Schultz PG, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6134–6139. doi: 10.1021/ja034099w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry AA, Olsen AG, Matsuda S, Yu C, Geierstanger BH, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6923–6931. doi: 10.1021/ja049961u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitsui T, Kimoto M, Harada Y, Yokoyama S, Hirao I. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8652–8658. doi: 10.1021/ja0425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Lee I, Zhou X, Berdis AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:143–149. doi: 10.1021/ja0546830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kojima N, Inoue K, Nakajimi-Shibata R, Kawahara S, Ohtsuka E. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:7175–7188. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spratt TE. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2647–2652. doi: 10.1021/bi002641c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leconte AM, Chen L, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12470–12471. doi: 10.1021/ja053322h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Waksman G. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1225–1233. doi: 10.1110/ps.250101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer AS, Blandino M, Spratt TE. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33043–33046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keefe AD, Cload ST. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shamah SM, Healy JM, Cload ST. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:130–138. doi: 10.1021/ar700142z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seeman NC. Mol Biotechnol. 2007;37:246–257. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0059-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seeman NC. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:119–235. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ieven M. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:259–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svarovskaia ES, Moser MJ, Bae AS, Prudent JR, Miller MD, Borroto-Esoda K. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4237–4241. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01512-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moser MJ, Christensen DR, Norwood D, Prudent JR. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:89–96. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pietz BC, Warden MB, DuChateau BK, Ellis TM. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:1174–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.08.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson SC, Marshall DJ, Harms G, Miller CM, Sherrill CB, Beaty EL, Lederer SA, Roesch EB, Madsen G, Hoffman GL, Laessig RH, Kopish GJ, Baker MW, Benner SA, Farrell PM, Prudent JR. Clin Chem. 2004;50:2019–2027. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.034330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Y, Fa M, Tae EL, Schultz PG, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14626–14630. doi: 10.1021/ja028050m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Creighton S, Bloom LB, Goodman MF. Methods Enzymol. 1995;262:232–256. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)62021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwang GT, Leconte AM, Romesberg FE. Chem Bio Chem. 2007;8:1606–1611. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hwang GT, Romesberg FE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2037–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim Y, Leconte AM, Hari Y, Romesberg FE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:7809–7812. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuda S, Henry AA, Romesberg FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6369–6375. doi: 10.1021/ja057575m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danilov VI. Mol Biol Rep. 1975;2:263–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00356997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson T, Zhu J, Wartell RM. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12343–12350. doi: 10.1021/bi981093o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bommarito S, Peyret N, SantaLucia J., Jr Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1929–1934. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.9.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.