Abstract

V-ATPases are structurally conserved and functionally versatile proton pumps found in all eukaryotes. The yeast V-ATPase has emerged as a major model system, in part because yeast mutants lacking V-ATPase subunits (vma mutants) are viable and exhibit a distinctive Vma-phenotype. Yeast vma mutants are present in ordered collections of all non-essential yeast deletion mutants, and a number of additional phenotypes of these mutants have emerged in recent years from genomic screens. This review summarizes the many phenotypes that have been associated with vma mutants through genomic screening. The results suggest that V-ATPase activity is important for an unexpectedly wide range of cellular processes. For example, vma mutants are hypersensitive to multiple forms of oxidative stress, suggesting an antioxidant role for the V-ATPase. Consistent with such a role, vma mutants display oxidative protein damage and elevated levels of reactive oxygen species, even in the absence of an exogenous oxidant. This endogenous oxidative stress does not originate at the electron transport chain, and may be extra-mitochondrial, perhaps linked to defective metal ion homeostasis in the absence of a functional V-ATPase. Taken together, genomic data indicate that the physiological reach of the V-ATPase is much longer than anticipated. Further biochemical and genetic dissection is necessary to distinguish those physiological effects arising directly from the enzyme’s core functions in proton pumping and organelle acidification from those that reflect broader requirements for cellular pH homeostasis or alternative functions of V-ATPase subunits.

Keywords: V-ATPase, yeast, vma mutant, acidification, genomic, oxidative stress

Introduction

Vacuolar proton-translocating ATPases (V-ATPases) are functionally diverse proton pumps with a highly conserved structure (Kane, 2006; Nishi & Forgac, 2002). In all eukaryotic cells, V-ATPases are responsible for acidification of a variety of organelles, including lysosomes/vacuoles, endosomes, and the late Golgi apparatus. In certain cells, they have also been adapted to export protons from the cytosol across the plasma membrane (Breton & Brown, 2007)Wieczorek et al., 1999). V-ATPases contribute to cellular pH control in all of these different cellular contexts.

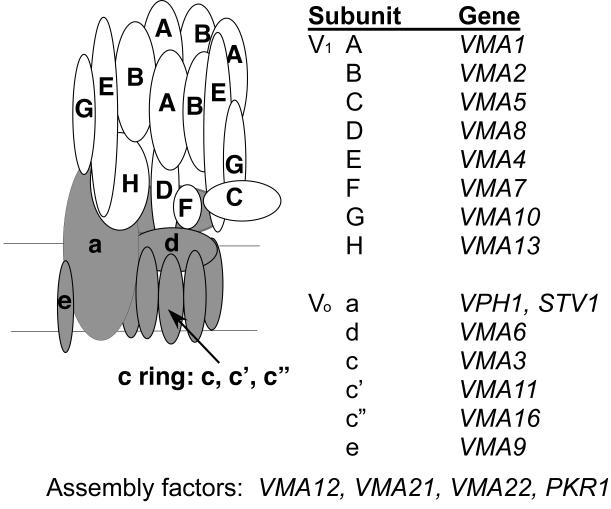

All eukaryotic V-ATPases have a very similar structure, consisting of approximately 14 subunits arranged into two subcomplexes: a peripheral membrane subcomplex called V1 and an integral membrane subcomplex designated Vo (Nishi & Forgac, 2002). In mammalian cells, many of these subunits exist as several tissue- or organelle-specific isoforms, but in yeast, all subunits except the Vo “a” subunit are encoded by a single gene (Figure 1). Deletion of any one of these genes, any of four assembly factors dedicated to the V-ATPase (Davis-Kaplan et al., 2006; Graham, Hill & Stevens, 1998), or both of the a subunit isoforms, results in a very similar phenotype. This Vma− phenotype, is characterized by a distinct pattern of pH and calcium sensitive growth, metal ion sensitivity, and inability to grow on non-fermentable carbon sources (Kane, 2006). In contrast, complete loss of V-ATPase activity in eukaryotes other than fungi is lethal, often at very early stages of development (Allan et al., 2005; Sun-Wada et al., 2000). Null mutations of subunit isoforms permit viability in some cases in metazoans, and result in specific defects characteristic of the sphere of influence of V-ATPases containing that specific isoform (Borthwick & Karet, 2002).

Figure 1.

Model of yeast V-ATPase structure and subunit gene designations. V1 subunits are shown in white, and Vo subunits are shown in grey in the model. VPH1 and STV1 encode two isoforms of the Vo a subunit.

Because yeast vma deletion mutants are viable, it is possible to assess the downstream consequences of abrogating V-ATPase function from the properties of the vma mutants. Both direct analysis of the vma mutants and phenotypic screens of ordered yeast deletion mutant arrays have revealed that loss of V-ATPase activity has unexpectedly diverse consequences. These results indicate that tight-control of pH and/or “moonlighting” functions of V-ATPase subunits are intertwined with a large number of cellular processes. In this review, we will describe the diverse functional connections to the V-ATPase revealed by yeast genomic screens in recent years, and then focus on recent data suggesting that V-ATPases may help to provide resistance to oxidative stress.

Genomic screens highlight widespread defects in vma mutants

The development of ordered deletion mutant arrays lacking individual, marked, non-essential yeast genes has permitted many non-biased genomic screens for specific growth phenotypes and inhibitor sensitivities (Giaever et al., 2002). In these screens, the collection of almost 5000 non-essential deletion mutants is tested for growth under varied conditions, and mutants with selectively compromised growth are identified. The resulting collection of mutants is further analyzed to look for enrichment of certain classes of genes. Statistically enriched classes can identify a complex or pathway that enables wild-type cells to grow under the conditions tested. Although it is certainly true that mutations can rather indirectly impact the ability of cells to grow under any given set of conditions, it is a significant advantage that genomic screens can potentially highlight the full scope of gene products required for growth, and provide evidence of important functional connections that were not appreciated previously. For example, this approach was used to screen the haploid non-essential deletion collection for all mutants exhibiting the classical Vma− phenotype, specifically, compromised growth at high pH and/or high calcium concentrations (Sambade et al., 2005; Serrano et al., 2004). These genomic screens identified almost all of the previously characterized V-ATPase subunits (in our screen, the strains lacking the other subunits were not represented in our library), as well as a previously unidentified subunit of the enzyme (Sambade & Kane, 2004) and a number of potential regulators (Sambade et al., 2005). A parallel screen also identified a novel assembly factor for the V-ATPase (Davis-Kaplan et al., 2004). All of these screens identified other strains that may have compromised vacuolar acidification.

In addition to their expected prominence in the total set of deletion mutants sensitive to elevated pH and high calcium, vma mutants emerged as a major class of mutants that display metabolic and morphological aberrations and sensitivity to a number of other treatments. As summarized in Table 1, vma mutants were overrepresented in genomic screens for: 1) sensitivity to multiple drugs, 2) sensitivity to elevated metal ion concentration, 3) sensitivity to limited iron availability, 4) sensitivity to both low and high extracellular calcium, 5) sensitivity to alcohol stress, 6) poor growth on high salt, 7) aberrant vacuolar morphology, 8) excess glycogen accumulation, 9) sensitivity to DNA damaging reagents, and 10) senstivity to multiple forms of oxidative stress (see Table 1 for references to specific screens). Some of these results may be readily explained by established roles of the vacuole in metal ion and calcium homeostasis, in nutrient storage and in sequestration of multiple metabolites and toxins (Klionsky, Herman & Emr, 1990). Additionally, V-ATPases that reside outside the vacuole may also have critical functions, as suggested by a recent study comparing the phenotypic consequences of V-ATPase activity loss to effects of losing Pmr1p, a calcium pump localized in the Golgi (Yadav et al., 2007). Other results, however, such as multidrug sensitivity and sensitivity to DNA damaging agents, are harder to incorporate into our current understanding of V-ATPase function, and suggest that the influence of the V-ATPase in overall cell physiology is far more extensive than anticipated.

Table 1.

Multiple phenotypes of yeast vma deletion mutants as revealed by genomic screening

| Phenotype targeted in genomic screen | Reference |

|---|---|

| Poor growth at elevated pH and extracellular calcium concentrations | {Sambade, 2005 #646} |

| Alkaline pH sensitivity | {Serrano, 2004 #539} |

| Sensitivity to organic acids | {Rand, 2006 #1283} |

| Poor growth under conditions of limited iron availability | {Davis-Kaplan, 2004 #547} |

| Poor growth at elevated metal or metalloid concentrations | {Eide, 1993 #1166; Hamilton, 2002 #1288; Gharieb, 1998 #1300} |

| Altered uptake and distribution of cellular iron | {Lesuisse, 2005 #580} |

| Poor NaCl tolerance | {Hamilton, 2002 #1290} |

| Multidrug hypersensitivity; vma mutants were hypersensitive to: cyclosporin A, FK506, fluconazole, sulfometuron methyl wortmannin, tunicamycin, caffiene, rapamycin, hydroxyurea, and cycloheximide |

{Parsons, 2004 #521} |

| Hypersensitivity to BAPTA (low Ca2+), amiodarone, and MnCl2 | {Yadav, 2007 #1280} |

| Hypersensitivity to DNA damaging agents (cisplatin) | {Liao, 2007 #1284} |

| Sensitivity to multiple oxidants | {Thorpe, 2004 #579} |

| Poor growth at high oxygen pressure | {Outten, 2005 #578} |

| Sensitivity to dithiothreitol (reductive stress) | {Rand, 2006 #1283} |

| Poor tolerance of ethanol and other alcohols | {Fujita, 2006 #1299} |

| Altered glycogen accumulation | {Wilson, 2002 #1287} |

| Perturbed vacuolar morphology; defective vacuolar protein sorting | {Seeley, 2002 #573; Bonangelino, 2002 #762} |

An antioxidant role for V-ATPases

One unexpected phenotype of the vma mutants revealed by genomic screens is hypersensitivity to oxidative stress (Outten, Falk & Culotta, 2005; Thorpe et al., 2004). Oxidative stress is an occupational hazard for cells growing in an oxygen environment (Imlay, 2003), and uncontrolled stress is implicated as an important factor in aging and multiple human disease states ranging from Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral schlerosis to diabetes (Davies, 1995; Valko et al., 2007). Many mechanisms for oxidative stress resistance, including superoxide dismutase, the glutathione buffer system, thioredoxins, and redox-sensitive transcription factors, are ancient and conserved, tuned to responding to stresses from different sources and/or in different intracellular locations (Carmel-Harel & Storz, 2000; Temple, Perrone & Dawes, 2005). Screening yeast deletion libraries for mutants with enhanced sensitivity to oxidative stress confirmed that deletions in these well-established systems compromised resistance to multiple oxidants (Outten et al., 2005; Thorpe et al., 2004). Surprisingly, these screens also indicated that loss of V-ATPase activity rendered cells sensitive to multiple oxidants, suggesting that V-ATPase activity also played a critical role in defending against oxidative stress.

We confirmed this result by testing two vma mutants, vma2Δ and vma3Δ, for sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide, the superoxide-generating agent menadione, and diamide (Milgrom et al., 2007). We found that the vma mutants were particularly sensitive to hydrogen peroxide, but also showed increased sensitivity to menadione and diamide. It was particularly striking that the sensitivity of vma mutants to hydrogen peroxide approached that of mutations lacking the cytosolic or mitochondrial superoxide dismutases (SODs), which are well-established as important antioxidant systems. This supports a critical antioxidant role for the V-ATPase. Many mutations that disrupt antioxidant mechanisms result in elevation of endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) and evidence of oxidative damage to protein, even in the absence of an exogenous oxidant (O’Brien et al., 2004). Consistent with this, we found significantly increased ROS and oxidative protein damage in the vma2Δ mutant, suggesting that these cells have an endogenous source of ROS that may be taxing the redox buffering system(Milgrom et al., 2007).

In recent years it has become clear that, in addition to promoting multiple forms of cell damage, ROS can play complex roles in signalling and adaptation and can originate from multiple sources (Temple et al., 2005; Valko et al., 2007). We explored possible sources of the excess endogenous ROS in the vma mutants. The respiratory chain can be a major source of reactive oxygen species (Dirmeier et al., 2002), and the failure of vma mutants to grow on non-fermentable carbon sources suggested the possibility that defective oxidative phosphorylation might give rise to enhanced oxidative stress. We tested this by examining the sensitivity of vma mutant cells lacking mitochondrial DNA (rho0 cell s) to oxidative stress. Yeast rho0 cells contain mitochondria, but lack an intact electron transport chain; in some cases, loss of mitochondrial DNA suppresses ROS production (Haynes, Titus & Cooper, 2004). The vma2Δ rho0 mutant did not show a significant decrease in ROS levels, however, and was at least as sensitive as the vma2Δ rho+ mutant to peroxide addition (Milgrom et al., 2007), suggesting that the source of oxidative stress in the mutants is non-mitochondrial. Furthermore, consistent with a cytosolic source of endogenous ROS, the sensitivity of the vma2Δ mutant to oxidative stress was exacerbated much more severely when the vma2 deletion was combined with a deletion in the cytosolic antioxidant systems (the trx2Δ, glr1Δ and sod1Δ mutations, which affect the cytosolic thioredoxin, glutathione, and superoxide dismutase defenses, respectively) than when combined with deletions in the mitochondrial antioxidant systems (trx3Δ, and sod2Δ, affecting the mitochondrial thioredoxin and superoxide dismutase, respectively) (Milgrom et al., 2007). In fact, combination of vma2Δ and sod1Δ mutations appeared to be lethal unless the vma2Δ mutation was complemented by a VMA2-containing plasmid. Taken together, these results suggest an extra-mitochondrial source of oxidative stress, but the exact nature of that stress and the primary source of ROS in the vma mutants remain to be determined.

Transcriptional profiling can also provide unique insights into the physiological state of a cell. Through microarray analysis, we compared mRNA levels from vma2Δ and wild-type cells grown under optimal conditions for the mutant (Milgrom et al., 2007). The set of genes upregulated in the vma2Δ mutant was most highly enriched in genes associated with two functional categories: 1) metal ion, and particularly iron, transport and homeostasis, and 2) arginine, glutamine, and ornithine biosynthesis and metabolism. In yeast, many of the iron transport and homeostasis genes (collectively called the “iron regulon”) are co-regulated under the control of two homologous but non-redundant transcription factors, Aft1p and Aft2p (Rutherford & Bird, 2004). The upregulation of the iron regulon is potentially significant in the context of oxidative stress, both because perturbed metal ion homeostasis may promote ROS formation, and because upregulation of these genes in response to oxidative stress had been reported previously (Belli et al., 2004; Pujol-Carrion et al., 2006). We tested one mechanism by which a cycle of iron deprivation and ROS production might be operating in the vma mutants. Yeast cells require an acidic compartment to support maturation of the high affinity iron transporter Fet3p/Ftr1p, so Fet3p does not mature in vma mutants and high-affinity iron transport is lost (Davis-Kaplan et al., 2004). It was possible that this in itself might potentiate oxidative stress by introducing a requirement for low affinity/low specificity transporters that less efficiently control influx of redox active metals (Li & Kaplan, 1998). We found, however, that a fet3Δ mutant, which completely lacks the high affinity iron transporter, is not much more sensitive to peroxide stress than the wild-type cells. Therefore, defective metal ion homeostasis is still a potential source of oxidative stress in the vma mutants, but iron deprivation does not fully explain this stress.

Significantly, most of the genes encoding typical antioxidant enzymes were not upregulated in the vma2Δ mutant. Acute oxidative stress generates a potent transcriptional response via the Yap1p and Skn7p transcription factors, which results in upregulation of much of the antioxidant machinery (Coleman et al., 1999; Lee et al., 1999). There was little evidence of activation of Yap1 or Skn7-regulated genes in the vma2Δ mutant, but one potential antioxidant gene, the cytosolic, stress-induced, thioredoxin peroxidase Tsa2p was highly upregulated. Thioredoxin peroxidases are capable of reducing reactive oxygen species such as H2O2 or organic hydroperoxides (Munhoz & Netto, 2004; Park et al., 2000), so it is possible that upregulation of TSA2 helps provde relief from oxidative stress in the vma2Δ mutant.

Why does loss of V-ATPase activity have such far-reaching effects?

As discussed above, the surprising antioxidant effects of the V-ATPase have a number of potential physiological explanations that can be readily explored. However, these results also highlight again the general question raised by the wide-ranging phenotypes associated with the vma mutants outlined in Table I; specifically, why does loss of V-ATPase activity have such far-reaching effects on cell physiology? Furthermore, it is entirely possible that these far-reaching effects are present not only in yeast, but in mammalian cells as well. The full range of these effects may not have been fully appreciated in animals because the current tools for abolishing V-ATPase activity are much more limited. Notably, not only is genetic loss of V-ATPase activity lethal at very early stages of mouse development (Sun-Wada et al., 2000), but treatment of a number of cell types with the specific V-ATPase inhibitors concanamycin A or bafilomycin A1 results in wide-ranging consequences, often culminating in cell death (De Milito et al., 2007; Manabe et al., 1993; Nishihara et al., 1995; Okahashi et al., 1997). These results indicate that the V-ATPase is centrally important in mammalian cells as well as yeast cells.

There is no question that the primary function of V-ATPases is proton pumping. In most eukaryotic cells, this pumping is directed toward organelle acidification, and organelle acidification in turn is important for a variety of other processes ranging from protein sorting and degradation to overall ion homeostasis (reviewed in (Kane, 2006; Paroutis, Touret & Grinstein, 2004)). Proton pumping into organelles is accompanied by removal of protons from the cytosol, but the extent to which V-ATPase activity makes a significant contribution to cytosolic pH homeostasis under normal growth conditions is somewhat unclear. There is clear evidence that their activity may become important for cytosolic pH control under certain conditions at least (Swallow et al., 1991; Swallow et al., 1993). We have recently found that the yeast vma mutants have dramatically perturbed cytosolic pH homeostasis (Martinez-Munoz and Kane, manuscript in preparation); therefore, cytosolic pH changes could help account for some of the unexpected defects of the yeast vma mutants. This overall perturbation in pH homeostasis in yeast may help to account for the central position of the V-ATPase in homeostasis of multiple other ions (Eide et al., 2005), and could even be contributing to the lifetime or distribution of ROS(Imlay, 2003), helping to explain the antioxidant function of V-ATPases.

It should also be noted, however, that certain V-ATPase subunits have been implicated in a number of “moonlighting functions” that appear to be separate from the enzyme’s proton pump function. The most prominent recent example of this is the proposed role of the Vo sector subunits in membrane-membrane fusion (Hiesinger et al., 2005; Peters et al., 2001). Disruption of such additional functions of the V-ATPase could also give rise to diverse phenotypes, but it should be noted that in these cases, only mutations in the subunits involved, i.e. the Vo subunits in the case of membrane fusion, should give rise to phenotypes arising from loss of fusion. Significantly, virtually all of the screens summarized in Table 1 identified vma genes encoding both V1 and Vo sector subunits.

Taken together, these data suggest that the long reach of V-ATPase function is likely to be rooted in one or more aspects of pH homeostasis. Sorting out how pH ultimately influences different aspects of cell physiology and determining how far removed the different phenotypes are from loss of V-ATPase activity in yeast will help to define the physiological reach of V-ATPase activity in mammalian cells and clarify the many facets of V-ATPase function.

Acknowledgements

Work in the author’s lab is supported by NIH grant GM50322. The author thanks Anne Smardon and Sheena Claire Li for critically reading the manuscript and apologizes for overlooking any genomic screens that identified vma mutants but are not specifically cited here.

References

- Allan AK, Du J, Davies SA, Dow JA. Genome-wide survey of V-ATPase genes in Drosophila reveals a conserved renal phenotype for lethal alleles. Physiol Genomics. 2005;22:128–38. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00233.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli G, Molina MM, Garcia-Martinez J, Perez-Ortin JE, Herrero E. Saccharomyces cerevisiae glutaredoxin 5-deficient cells subjected to continuous oxidizing conditions are affected in the expression of specific sets of genes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12386–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonangelino CJ, Chavez EM, Bonifacino JS. Genomic screen for vacuolar protein sorting genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2486–501. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthwick KJ, Karet FE. Inherited disorders of the H+-ATPase. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2002;11:563–8. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton S, Brown D. New insights into the regulation of V-ATPase-dependent proton secretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1–10. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00340.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel-Harel O, Storz G. Roles of the glutathione- and thioredoxin-dependent reduction systems in the Escherichia coli and saccharomyces cerevisiae responses to oxidative stress. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:439–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman ST, Epping EA, Steggerda SM, Moye-Rowley WS. Yap1p activates gene transcription in an oxidant-specific fashion. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8302–13. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies KJ. Oxidative stress: the paradox of aerobic life. Biochem Soc Symp. 1995;61:1–31. doi: 10.1042/bss0610001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Kaplan SR, Compton MA, Flannery AR, Ward DM, Kaplan J, Stevens TH, Graham LA. PKR1 encodes an assembly factor for the yeast V-type ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32025–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Kaplan SR, Ward DM, Shiflett SL, Kaplan J. Genome-wide analysis of irondependent growth reveals a novel yeast gene required for vacuolar acidification. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4322–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310680200. Epub 2003 Nov 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Milito A, Iessi E, Logozzi M, Lozupone F, Spada M, Marino ML, Federici C, Perdicchio M, Matarrese P, Lugini L, Nilsson A, Fais S. Proton pump inhibitors induce apoptosis of human B-cell tumors through a caspase-independent mechanism involving reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5408–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirmeier R, O’Brien KM, Engle M, Dodd A, Spears E, Poyton RO. Exposure of yeast cells to anoxia induces transient oxidative stress. Implications for the induction of hypoxic genes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34773–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide DJ, Bridgham JT, Zhao Z, Mattoon JR. The vacuolar H(+)-ATPase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for efficient copper detoxification, mitochondrial function, and iron metabolism. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;241:447–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00284699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide DJ, Clark S, Nair TM, Gehl M, Gribskov M, Guerinot ML, Harper JF. Characterization of the yeast ionome: a genome-wide analysis of nutrient mineral and trace element homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R77. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-9-r77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Matsuyama A, Kobayashi Y, Iwahashi H. The genome-wide screening of yeast deletion mutants to identify the genes required for tolerance to ethanol and other alcohols. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:744–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharieb MM, Gadd GM. Evidence for the involvement of vacuolar activity in metal(loid) tolerance: vacuolar-lacking and -defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae display higher sensitivity to chromate, tellurite and selenite. Biometals. 1998;11:101–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1009221810760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever G, Chu AM, Ni L, Connelly C, Riles L, Veronneau S, Dow S, Lucau-Danila A, Anderson K, Andre B, Arkin AP, Astromoff A, El-Bakkoury M, Bangham R, Benito R, Brachat S, Campanaro S, Curtiss M, Davis K, Deutschbauer A, Entian KD, Flaherty P, Foury F, Garfinkel DJ, Gerstein M, Gotte D, Guldener U, Hegemann JH, Hempel S, Herman Z, Jaramillo DF, Kelly DE, Kelly SL, Kotter P, LaBonte D, Lamb DC, Lan N, Liang H, Liao H, Liu L, Luo C, Lussier M, Mao R, Menard P, Ooi SL, Revuelta JL, Roberts CJ, Rose M, Ross-Macdonald P, Scherens B, Schimmack G, Shafer B, Shoemaker DD, Sookhai-Mahadeo S, Storms RK, Strathern JN, Valle G, Voet M, Volckaert G, Wang CY, Ward TR, Wilhelmy J, Winzeler EA, Yang Y, Yen G, Youngman E, Yu K, Bussey H, Boeke JD, Snyder M, Philippsen P, Davis RW, Johnston M. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418:387–91. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham LA, Hill KJ, Stevens TH. Assembly of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and requires a Vma12p/Vma22p assembly complex. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:39–49. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CA, Taylor GJ, Good AG. Vacuolar H(+)-ATPase, but not mitochondrial F(1)F(0)-ATPase, is required for NaCl tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;208:227–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes CM, Titus EA, Cooper AA. Degradation of misfolded proteins prevents ERderived oxidative stress and cell death. Mol Cell. 2004;15:767–76. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiesinger PR, Fayyazuddin A, Mehta SQ, Rosenmund T, Schulze KL, Zhai RG, Verstreken P, Cao Y, Zhou Y, Kunz J, Bellen HJ. The v-ATPase V0 subunit a1 is required for a late step in synaptic vesicle exocytosis in Drosophila. Cell. 2005;121:607–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay JA. Pathways of oxidative damage. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:395–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane PM. The where, when, and how of organelle acidification by the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:177–91. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.177-191.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahata M, Masaki K, Fujii T, Iefuji H. Yeast genes involved in response to lactic acid and acetic acid: acidic conditions caused by the organic acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cultures induce expression of intracellular metal metabolism genes regulated by Aft1p. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:924–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Herman PK, Emr SD. The fungal vacuole: composition, function, and biogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:266–92. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.3.266-292.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Godon C, Lagniel G, Spector D, Garin J, Labarre J, Toledano MB. Yap1 and Skn7 control two specialized oxidative stress response regulons in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16040–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesuisse E, Knight SA, Courel M, Santos R, Camadro JM, Dancis A. Genome-Wide Screen for Genes With Effects on Distinct Iron Uptake Activities in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005;169:107–22. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.035873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Kaplan J. Defects in the yeast high affinity iron transport system result in increased metal sensitivity because of the increased expression of transporters with a broad transition metal specificity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22181–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C, Hu B, Arno MJ, Panaretou B. Genomic screening in vivo reveals the role played by vacuolar H+ ATPase and cytosolic acidification in sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents such as cisplatin. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:416–25. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe T, Yoshimori T, Henomatsu N, Tashiro Y. Inhibitors of vacuolar-type H(+)-ATPase suppresses proliferation of cultured cells. J Cell Physiol. 1993;157:445–52. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041570303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom E, Diab H, Middleton F, Kane PM. Loss of vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase activity in yeast results in chronic oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7125–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munhoz DC, Netto LE. Cytosolic thioredoxin peroxidase I and II are important defenses of yeast against organic hydroperoxide insult: catalases and peroxiredoxins cooperate in the decomposition of H2O2 by yeast. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35219–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi T, Forgac M. The vacuolar (h+)-ATPases - nature’s most versatile proton pumps. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:94–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara T, Akifusa S, Koseki T, Kato S, Muro M, Hanada N. Specific inhibitors of vacuolar type H(+)-ATPases induce apoptotic cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:255–62. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien KM, Dirmeier R, Engle M, Poyton RO. Mitochondrial protein oxidation in yeast mutants lacking manganese-(MnSOD) or copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD): evidence that MnSOD and CuZnSOD have both unique and overlapping functions in protecting mitochondrial proteins from oxidative damage. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51817–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okahashi N, Nakamura I, Jimi E, Koide M, Suda T, Nishihara T. Specific inhibitors of vacuolar H(+)-ATPase trigger apoptotic cell death of osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1116–1123. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.7.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outten CE, Falk RL, Culotta VC. Cellular factors required for protection from hyperoxia toxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J. 2005 doi: 10.1042/BJ20041914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SG, Cha MK, Jeong W, Kim IH. Distinct physiological functions of thiol peroxidase isoenzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5723–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paroutis P, Touret N, Grinstein S. The pH of the secretory pathway: measurement, determinants, and regulation. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:207–15. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00005.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons AB, Brost RL, Ding H, Li Z, Zhang C, Sheikh B, Brown GW, Kane PM, Hughes TR, Boone C. Integration of chemical-genetic and genetic interaction data links bioactive compounds to cellular target pathways. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:62–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters C, Bayer MJ, Buhler S, Andersen JS, Mann M, Mayer A. Trans-complex formation by proteolipid channels in the terminal phase of membrane fusion. Nature. 2001;409:581–8. doi: 10.1038/35054500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol-Carrion N, Belli G, Herrero E, Nogues A, de la Torre-Ruiz MA. Glutaredoxins Grx3 and Grx4 regulate nuclear localisation of Aft1 and the oxidative stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4554–64. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand JD, Grant CM. The thioredoxin system protects ribosomes against stress-induced aggregation. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:387–401. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford JC, Bird AJ. Metal-responsive transcription factors that regulate iron, zinc, and copper homeostasis in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:1–13. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.1.1-13.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambade M, Alba M, Smardon AM, West RW, Kane PM. A genomic screen for yeast vacuolar membrane ATPase mutants. Genetics. 2005;170:1539–51. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.042812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambade M, Kane PM. The yeast vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase contains a subunit homologous to the Manduca sexta and bovine e subunits that is essential for function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17361–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley ES, Kato M, Margolis N, Wickner W, Eitzen G. Genomic analysis of homotypic vacuole fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:782–94. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano R, Bernal D, Simon E, Arino J. Copper and iron are the limiting factors for growth of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in an alkaline environment. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19698–704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313746200. Epub 2004 Mar 01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun-Wada G, Murata Y, Yamamoto A, Kanazawa H, Wada Y, Futai M. Acidic endomembrane organelles are required for mouse postimplantation development. Dev Biol. 2000;228:315–25. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swallow CJ, Grinstein S, Sudsbury RA, Rotstein OD. Cytoplasmic pH regulation in monocytes and macrophages: mechanisms and functional implications. Clin Invest Med. 1991;14:367–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swallow CJ, Grinstein S, Sudsbury RA, Rotstein OD. Relative roles of Na+/H+ exchange and vacuolar-type H+ ATPases in regulating cytoplasmic pH and function in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 1993;157:453–60. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041570304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple MD, Perrone GG, Dawes IW. Complex cellular responses to reactive oxygen species. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:319–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe GW, Fong CS, Alic N, Higgins VJ, Dawes IW. Cells have distinct mechanisms to maintain protection against different reactive oxygen species: oxidative-stress-response genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6564–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305888101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek H, Brown D, Grinstein S, Ehrenfeld J, Harvey WR. Animal plasma membrane energization by proton-motive V-ATPases. Bioessays. 1999;21:637–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199908)21:8<637::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WA, Wang Z, Roach PJ. Systematic identification of the genes affecting glycogen storage in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implication of the vacuole as a determinant of glycogen level. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:232–42. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m100024-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav J, Muend S, Zhang Y, Rao R. A phenomics approach in yeast links proton and calcium pump function in the Golgi. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1480–9. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]