Abstract

Selective delivery of antisense or siRNA oligonucleotides to cells and tissues via receptor-mediated endocytosis is becoming an important approach for oligonucleotide-based pharmacology. In most cases receptor targeting has been attained using antibodies or peptide-type ligands. Thus there are few examples of delivering oligonucleotides using the plethora of small-molecule receptor-specific ligands that currently exist. In this report we describe a facile approach to the generation of mono- and multi-valent conjugates of oligonucleotides with small molecule ligands. Using the sigma receptor ligand anisamide as an example, we describe conversion of the ligand to a phosphoramidite and direct incorporation of this moiety into the oligonucleotide by solid phase DNA synthesis. We generated mono- and tri-valent conjugates of anisamide with a splice switching antisense oligonucleotide (SSO) and tested their ability to modify splicing of a reporter gene (luciferase) in tumor cells in culture. The tri-valent anisamide-SSO conjugate displayed enhanced cellular uptake and was markedly more effective than an unconjugated SSO or the mono-valent conjugate in modifying splicing of the reporter. Significant biological effects were attained in the sub-100 nM concentration range.

Targeted delivery is a key issue for the pharmacology of antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides.1 Receptor-specific ligands can be linked to various nanocarriers that contain oligonucleotides, or they can be directly conjugated to the oligonucleotide itself. For example, we recently showed that conjugation of a dimeric RGD (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid) peptide, a high-affinity ligand for the integrin αvβ3, to an oligonucleotide (ON) increased cellular uptake via receptor-mediated endocytosis and enhanced the biological effect of the ON. 2 Thus, direct mono- or multi-valent ligand conjugation to ONs seems an attractive strategy for enhancing receptor specific delivery of ONs to cells and tissues while using well-defined chemical moieties. In this report, we describe the synthesis of mono- and multi-valent oligonucleotide conjugates using anisamide, a high affinity ligand for sigma receptors, and evaluation of the function of these conjugates in tumor cells in culture.

Sigma receptors (σ1, σ2) are transmembrane proteins, found on the endoplasmic reticulum and on plasma membranes that seem to play a role in regulating ion channels.3 High level expression of sigma receptors has been observed for a diverse set of human and rodent tumor cell lines. 4 Small molecules such as haloperidol, SA4503 and opipramol have been reported as sigma-receptor ligands.3 Several σ1 ligands have been developed as radioimaging agents for tumors and successfully tested in vivo.5 These observations suggested that sigma receptor ligands could also be used for targeted drug delivery. Thus Huang and colleagues have reported that the high affinity sigma-receptor ligand anisamide, when conjugated to lipid nanocarriers, could be used to deliver doxorubicin 6 or siRNA 7 to tumors in animals. Mukherjee et al. reported that haloperidol conjugated lipoplexes showed 10-fold greater delivery of DNA to breast carcinoma cells than did control lipoplexes. 8

For liposome-conjugated anisamide (N-2-aminoethyl 4-methoxy-benzamide), the 4-methoxy-benzamide unit itself is very important for binding activity to sigma receptor. In addition, the aminoethyl moiety, especially the terminal nitrogen, is also important. 6,9 Interestingly, DeSimone et al. developed a new anisamide ligand that used a modification with an oxygen atom, instead of a nitrogen atom in the aminoethyl moiety. 10

With the intent of establishing an efficient strategy for ligand-oligonucleotide conjugation, we designed the direct incorporation of anisamide ligand into antisense oligonucleotides using a DNA synthesizer. Thus, we used N-2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethyl 4-methoxy-benzamide (1) for direct conjugation to ONs. This allows solid phase synthesis of anisamide-ON conjugates, since a protective group is not needed during DNA synthesis (Scheme 1 and Supporting information). The phosphitylation of the anisamide 1 successfully afforded the phosphoramidite 2. The anisamide phosphoramidite 2 was incorporated into oligonucleotides using conventional phosphoramidite chemistry on an automated DNA synthesizer. For the mono-anisamide conjugate, 2 was directly incorporated at the 5′-terminal of the ON. The tri-valent conjugate was synthesized using a three-branched linker readily introduced into the 5′-terminal of the ON. The facile synthesis described here should be readily applicable to various other types of oligonucleotides such as siRNA, miRNA, triplex forming oligonucleotides, and molecular decoys.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 5′ mono-, tri-valent anisamide-conjugated oligonucleotides. ON (623): 5′-GTT ATT CTT TAG AAT GGT GC-TAMRA-3′ (2′-O-Me RNA with phosphorothioate backbone). Reagents and conditions: (a) iPr2NP(Cl)OCH2CH2CN, iPr2NEt, CH2Cl2, (b) DNA synthesizer, HPLC purification.

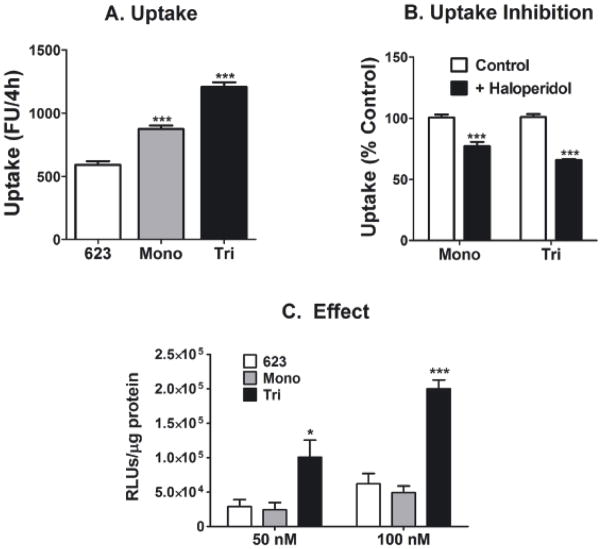

To evaluate biological activity of the conjugates, we utilized sigma-receptor expressing cells (PC3, human prostate carcinoma cells) that contain a luciferase reporter gene interrupted by an abnormal intron that prevents expression of functional luciferase protein. 11 Upon adequate delivery of an appropriate splice-switching antisense oligonucleotide (an SSO, here designated ON 623) to the nucleus, the intron is spliced out and luciferase is expressed.11 The 623 ONs were 2′-O-methyl RNA with a phosphorothioate backbone and a 3’ TAMRA fluorophore. Uptake of the fluorescent ONs was monitored in cells by flow cytometry. 2 As seen in Figure 1A, there was slightly higher uptake of the mono-anisamide conjugate as compared to the unconjugated ON control, while the trivalent-anisamide conjugate showed significantly greater uptake than control, possibly reflecting greater avidity of the multi-valent version for the sigma receptor. The increased uptake could be partially blocked by co-incubation with excess free haloperidol (Figure 1B), a strong sigma-receptor antagonist. Since the overall uptake process likely involves both receptor mediated endocytosis and non-specific fluid phase pinocytosis, it is expected that the blocking effect of an antagonist would be partial.

Figure 1.

A. Initial cellular uptake. Cells were treated with 50 nM mono-anisamide-623-TAMRA, tri-anisamide-623-TAMRA, or 623-TAMRA, for 4 hours in OptiMEM at 37°C. The cells were rinsed in buffered saline solution and then trypsinized. Total cellular uptake of the TAMRA-labeled conjugate was measured by flow cytometry. B. Effect of sigma receptor inhibitor on initial uptake. Cells were treated with 50 nM mono-or tri-anisamide-623-TAMRA in the absence or presence of 50 μM haloperidol. After 4 hours, the cellular uptake was measured by flow cytometry. Results are normalized based on cells receiving no inhibitor as 100%. C. Luciferase induction. Cells were treated with mono-anisamide-623-TARMA, tri-anisamide-623-TAMRA, or 623-TAMRA for 24 hours and luciferase activity was determined 48 hours after treatment. Results A-C are the means and standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

The biological effect (luciferase induction) paralleled the uptake data, but was more pronounced. The tri-valent conjugate displayed a significantly greater effect than the monovalent compound or the unconjugated control (Figure 1C). Consistent with our previous observations 2 the biological effects of oligonucleotides entering cells by a receptor mediated process seem to be greater than those of oligonucleotides entering by pinocytosis. Thus, as compared to the unmodified oligonucleotide, the trivalent conjugate displayed an approximate two-fold increase in uptake but a four-fold increase in luciferase induction. No toxicities were apparent with use of these conjugates as judged by the retention of normal cell morphology and lack of effect on total cell protein recovered.

Thus we have demonstrated the facile production of mono- and tri-valent anisamide conjugated oligonucleotides via conversion of the ligand to a phosphoramidite followed by conventional solid phase ON synthesis. The multi-valent anisamide conjugate significantly enhanced receptor-specific cell uptake and biological effect. While there has been considerable work on peptide-oligonucleotide conjugates 12, relatively little has been done with oligonucleotides linked to small organic molecules. The novel conjugation approach described here should create opportunities to utilize a variety of highly selective small molecule ligands to target various receptor types, including members of the numerous G-protein Coupled Receptor family 13, thus enhancing possibilities for receptor-selective ON delivery to a wide variety of cells and tissues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH [PO1GM 26599] to R.L.J.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Synthesis of mono- and trivalent conjugated oligonucleotides and cell culture experiments. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:129–138. doi: 10.1038/nrd2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Juliano R, Bauman J, Kang H, Ming X. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:686–695. doi: 10.1021/mp900093r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bennett CF, Swayze EE. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Corey DR. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3615–3622. doi: 10.1172/JCI33483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Tiemann K, Rossi JJ. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:142–51. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Alam MR, Dixit V, Kang H, Li ZB, Chen X, Trejo J, Fisher M, Juliano RL. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2764–2776. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alam MR, Ming X, Dixit V, Fisher M, Chen X, Juliano RL. Oligonucleotides. 2010 doi: 10.1089/oli.2009.0211. e-publication, ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Maurice T, Su TP. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;124:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cobos EJ, Entrena JM, Nieto FR, Cendan CM, Del Pozo E. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2008;6:344–366. doi: 10.2174/157015908787386113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilner BJ, John CS, Bowen WD. Cancer Res. 1995;55:408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John CS, Vilner BJ, Geyer BC, Moody T, Bowen WD. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4578–4583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee R, Tyagi P, Li S, Huang L. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:693–700. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Li SD, Chono S, Huang L. Mol Ther. 2008;16:942–946. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chono S, Li SD, Conwell CC, Huang L. J Control Release. 2008;131:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukherjee A, Prasad TK, Rao NM, Banerjee R. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15619–15627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ablordeppey SY, Fischer JB, Glennon RA. Bioorg Med Chem. 2000;8:2105–2111. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeSimone JM, Murphy AJ, Galloway A, Petros RA. WO/2008/045486 2008

- 11.Sazani P, Kole R. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:481–486. doi: 10.1172/JCI19547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Juliano RL. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2005;7:132–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Abes R, Arzumanov AA, Moulton HM, Abes S, Ivanova GD, Iversen PL, Gait MJ, Lebleu B. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:775–779. doi: 10.1042/BST0350775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Juliano R, Alam MR, Dixit V, Kang H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4158–4171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Cesarone G, Edupuganti OP, Chen CP, Wickstrom E. Bioconj Chem. 2007;18:1831–40. doi: 10.1021/bc070135v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armbruster BN, Roth BL. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5129–5132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.