Abstract

Dinucleoside tetraphosphates are common constituents of the cell and are thought to play diverse biological roles in organisms ranging from bacteria to humans. In this study we characterized two independent mechanisms by which di-adenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) metabolism impacts biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Null mutations in apaH, the gene encoding nucleoside tetraphosphate hydrolase, resulted in a marked increase in the cellular level of Ap4A. Concomitant with this increase, Pho regulon activation in low-inorganic-phosphate (Pi) conditions was severely compromised. As a consequence, an apaH mutant was not sensitive to Pho regulon-dependent inhibition of biofilm formation. In addition, we characterized a Pho-independent role for Ap4A metabolism in regulation of biofilm formation. In Pi-replete conditions Ap4A metabolism was found to impact expression and localization of LapA, the major adhesin regulating surface commitment by P. fluorescens. Increases in the level of c-di-GMP in the apaH mutant provided a likely explanation for increased localization of LapA to the outer membrane in response to elevated Ap4A concentrations. Increased levels of c-di-GMP in the apaH mutant were associated with increases in the level of GTP, suggesting that elevated levels of Ap4A may promote de novo purine biosynthesis. In support of this suggestion, supplementation with adenine could partially suppress the biofilm and c-di-GMP phenotypes of the apaH mutant. We hypothesize that changes in the substrate (GTP) concentration mediated by altered flux through nucleotide biosynthetic pathways may be a significant point of regulation for c-di-GMP biosynthesis and regulation of biofilm formation.

The dinucleoside polyphosphates (Ap4N) are a diverse group of nucleotide derivatives that are known constituents of virtually every cell type, from human cells to bacteria (20). One of the most studied of these compounds is di-adenosine 5′5‴-P1,P4-tetraphosphate (Ap4A). Alterations in the intracellular levels of Ap4A have been correlated with a variety of phenotypes in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic systems (1, 11, 29). In mammalian systems, Ap4A has been implicated in regulation of vasodilation, platelet aggregation, synaptic neurotransmission, and cell cycle control (20). In bacteria, Ap4A metabolism has been implicated in regulation of the stress response (5), pathogenesis (18), and antibiotic tolerance (16).

Early studies of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium demonstrated that treatment of cells with oxidizing agents results in large increases in the intracellular concentration of Ap4A, as well as large increases in the intracellular concentrations of related dinucleoside polyphosphates (5). Ap4A was suggested to be an “alarmone” that signals the onset of oxidative stress. The role of Ap4A as an alarmone in bacteria is still controversial, largely due to a lack of understanding of how changes in the Ap4A concentration are sensed and responded to by the cell.

Ap4A is thought to be synthesized in vivo by a side reaction during aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis (6, 30). In this scenario, the enzyme-bound aminoacyl adenylate intermediate is attacked by the pyrophosphate group of ATP, resulting in formation of Ap4A rather than aminoacyl-tRNA. Nucleophilic attack by other nucleotides results in formation of a variety of dinucleoside polyphosphates; however, Ap4A is the predominant species due to the high concentration of ATP in cells.

Specific enzymes have evolved to degrade Ap4A and other related dinucleoside polyphosphates (12). In Escherichia coli the major enzyme for Ap4A degradation is ApaH. Mutation of the apaH gene results in a >100-fold increase in the steady-state level of Ap4A compared to the wild-type level (10). Interestingly, the apaH mutation is pleiotropic, resulting in loss of motility (10) and increased sensitivity to heat and oxidative stress (19), as well as defects in catabolite repression (10).

In a previous paper, we reported the results of a genetic screen designed to identify factors that are required for Pho regulon activation when Pseudomonas fluorescens is growing in inorganic phosphate (Pi)-limiting conditions (25). In addition to the known Pi-dependent regulators, PhoB and PhoR, we isolated numerous strains with mutations in genes that potentially impact Pho regulon expression. One strain was identified as having a mutation in a gene similar to apaH from E. coli. In this paper, we characterize this strain with respect to the role of Ap4A metabolism in controlling Pho regulon expression and describe a novel role for Ap4A metabolism in modulating biofilm formation by P. fluorescens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. fluorescens and E. coli were routinely cultured in lysogeny broth (LB) unless stated otherwise and were grown at 30°C and 37°C, respectively (2). K10Tπ medium was used for Pi-limiting conditions and consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.2% (wt/vol) Bacto tryptone, 0.15% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 0.61 mM Mg2SO4 (25). K10T-1 medium was utilized as the medium for Pi-sufficient conditions and consisted of K10Tπ medium amended with 1 mM K2HPO4. TSP salts were prepared as described previously (25).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169(φ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 thi-1 relA1 recA1 | 15 |

| S17-1(λpir) | thi pro hsdR hsdM+ ΔrecA RP4-2::TcMu-Km::Tn7 | 37 |

| Top10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR nupG recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL(Strr) endA1 | Invitrogen |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens strains | ||

| Pf0-1 | Wild type | 9 |

| ΔlapD | Clean deletion of lapD in Pf0-1 | 27 |

| ΔlapD apaH | ΔlapD::pKO-apaH Tcr | This study |

| lapA | Pf0-1::pUC-lapA Kmr | This study |

| lapA apaH | Pf0-1::pUC-lapA::pKO-apaH Tcr Kmr | This study |

| Δpst | Pf0-1 with deletion of pstSCAB-phoU; Gmr | 25 |

| Δpst apaH | Δpst::pKO-apaH Tcr Gmr Tcr | 25 |

| Pfl_5137/apaH | Pf0-1::pKO-apaH Tcr | 25 |

| PF-B337 | Pf0-1 Pfl_5137::mini-Tn5 lacZ1(Km) Kmr | 25 |

| PF-013 | Pf0-1 lapA-HA | 24 |

| PF-201 | Pf0-1 lapA-HA::pKO-apaH | This study |

| PF-001 | Pf0-1::pUC-PlapA-luc Kmr | 24 |

| PF-203 | apaH::pUC-PlapA-luc Kmr Tcr | This study |

| PF-204 | Pf0-1::pUC-PphoX-luc Kmr | 25 |

| PF-205 | apaH::pUC-PphoX-luc Kmr Tcr | This study |

| PF-206 | Pf0-1::Tn7-Ppst-luc Kmr | This study |

| PF-207 | apaH::Tn7-Ppst-luc Kmr Tcr | This study |

| PF-208 | Pf0-1::pUC-PrplU-luc Kmr | This study |

| PF-209 | apaH::pUC-PrplU-luc Kmr Tcr | This study |

| PF-004 | Pf0-1::pUC-PlapE-luc Kmr | 24 |

| PF-210 | apaH::pUC-PlapE-luc Kmr Tcr | This study |

| PF-211 | PF-013 Plac::lapA | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBRMCS-2 | Broad-host-range cloning vector; Kmr | 21 |

| pBB-apaH (pBB-5137) | pBBRMCS-2 expressing apaH (Pfl_5137 ORF) | 25 |

| pBB-lapA | lapA expression vector for Pseudomonas; Kmr | This study |

| pHRB2 | pUC18T-Tn7T containing Km gene from pZE21-MCS2; Kmr | 25 |

| pKO3 | Pseudomonas integration vector; multiple cloning site, oriT lacZ′; Tcr | 25 |

| pLapA | Clone of lapA ORF; Gmr | This study |

| pMQ71B | pMQ71 modified to remove aacC1; Knr | 25 |

| pMQ72 | Pseudomonas expression vector; Gmr | 36 |

| pLapEBC | lapEBC genes expressed via PBAD promoter | 24 |

| pMQ-His-apaH | pMQ72 expressing N-terminal His-tagged apaH | This study |

| pMQ-Plac-lapA | Vector used to place Plac promoter in front of lapA ORF; Gmr | This study |

| pTn7-Ppst-luc | Tn7 delivery vector for Ppst luciferase fusion; Apr Kmr | This study |

| pUC18T-Tn7T | Mini-Tn7 vector; Apr | 8 |

| pUC-lucK | Vector used for construction of luciferase transcription fusions; Kmr | 25 |

| pUC-PlapA-luc | pUC-lucK with PlapA luciferase fusion; Kmr | 24 |

| pUC-PlapE-luc | pUC-lucK with PlapE luciferase fusion; Kmr | 24 |

| pUC-PphoX-luc | pUC-lucK with PphoX luciferase fusion; Kmr | 25 |

| pUC-PrapA-luc | pUC-lucK with PrapA luciferase fusion; Kmr | This study |

| pUC-PrplU-luc | pUC-lucK with PrplU luciferase fusion; Kmr | This study |

| pUX-BF13 | Tn7 helper plasmid encoding Tn7 transposition functions; Apr | 39 |

Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations, unless otherwise stated: ampicillin (Ap), 100 μg/ml; kanamycin (Km), 50 μg/ml; tetracycline (Tc), 10 to 15 μg/ml for E. coli and 30 μg/ml for P. fluorescens; gentamicin (Gm), 30 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol (Cm), 20 μg/ml.

Gene ID numbers for P. fluorescens Pf0-1 were obtained from the Complete Microbial Resource (http://cmr.jcvi.org/cgi-bin/CMR/CmrHomePage.cgi). However, small differences in nomenclature are in common use. For instance, NCBI uses the same gene numbers but a different prefix (Pfl01 instead of Pfl).

Luciferase transcriptional fusions.

Construction of luciferase fusions to the pstS and phoX genes was described in a previous report (25). Construction of luciferase fusions to the lapA and lapE genes was described in another previous report (24). Fusions to rapA were constructed using a method identical to that described for the phoX fusion. The rapA promoter was amplified with primers rapA-ncoI-R (CGA CGT CCAT GGC AAT CTC TGG CGA TAA) and rapA-bglII-F (GGT TTA AGA TCT GCG AAC TGA AAC TGA CTC TGG). Luciferase assays were performed as described previously, with one minor modification (24). Strains were grown for 13 h in LB before back-dilution in the medium in order to minimize the time that cultures were in stationary phase. This better synchronized the growth of the wild-type and apaH strains.

Purification of ApaH.

ApaH was purified by utilizing an N-terminal His tag. The apaH open reading frame (ORF) was amplified with primers apaH-His-F (ATT AAA GAG GAG AAA TTA ACT ATG CAT CAC CAT CAC CAT CAC CAT CAC CAT CAC ATG GCG ACG TAT GCC GTC) and apaH-His-R (GCC AAG CTT GCA TGC CTG CAG GTC GAC TCT AGA GGA TCC CCA TTC GCT CAT GGC GGG CTC C) and then cloned into pMQ72 using yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) in vivo recombination (36) and the linker fragment QE-His (ATA CCC GTT TTT TTG GGC TAG CGA ATT CGA GCT CGG TAC CCA TTA AAG AGG AGA AAT TAA CTA TGC ATC ACC ATC ACC ATC), generating pMQ-His-apaH. To purify ApaH and derivatives of this protein, E. coli strain Top10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) harboring pMQ-His-apaH, as well as the chaperone-expressing plasmids pBB540 and pBB542, was grown overnight in LB containing Gm, spectinomycin (Spec), and Cm and then back-diluted 1:100 in 1 liter of fresh LB containing Gm, Spec, and Cm and incubated with shaking at 37°C. At an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5, expression of ApaH was induced by addition of arabinose to a final concentration of 0.1% and incubation for 3 h at 30°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in binding buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.4], 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole). EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was added according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the cells were lysed with a French press. The lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min, and the soluble fraction was recovered by decanting the supernatant. Genomic DNA was subsequently sheared by passing the supernatant through a 25-gauge needle and then loaded onto a 5-ml HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) attached to a BioLogic LP low-pressure chromatography system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The column was washed with binding buffer before His-ApaH was eluted using an imidazole gradient according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fractions containing ApaH were pooled and concentrated using an Amicon Ultracel 10,000-molecular-weight-cutoff (MWCO) column (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and then were dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)-200 mM NaCl-10 mM MgCl2 using a Slide-A-Lyzer 10,000-MWCO dialysis cassette (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

ApaH activity assay.

Ap4A hydrolysis assays were performed as follows. Different concentrations of purified ApaH (0 to 1 mg/ml) were added to reaction mixtures (total volume, 20 μl) containing 1.25 mM Ap4A, 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 1 h before heat treatment at 65°C for 15 min. The reaction mixtures were then separated and visualized using a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) method essentially as described previously (14). Briefly, 5-μl portions of reaction mixtures were spotted onto TLC plates (with an aluminum backing and precoated with silica gel containing a fluorescent indicator; Merck catalog no. 5554). The plates were air dried and run in buffer containing dioxane, ammonium bicarbonate (29%), and water (6:1:4, by volume). After 2 h the plates were removed, air dried, and visualized under UV light.

In vivo nucleotide analysis. (i) Whole-cell labeling and 2D-TLC.

Whole-cell [32P]orthophosphate labeling and acid extraction were carried out as described previously (24). Two-dimensional TLC (2D-TLC) separation of nucleic acid extracts was performed as described previously (4, 22). Briefly, 6 to 8 μl of extract was spotted onto cellulose polyethyleneimine (PEI) TLC plates (Selecto Scientific, Suwanee, GA) and dried. Then the plates were developed using the first-dimension buffer (1.75 M morpholine, 0.1 M boric acid, 1.4 M HCl). After air drying, the plates were rotated 90° counterclockwise, developed using the second-dimension buffer [3 M (NH4)2SO4, 2% EDTA; pH 5.5], air dried, and exposed to storage phosphor screens (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). After overnight exposure the phosphor screens were read with a Storm 860 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

(ii) Mass spectrometry.

Cultures were grown in LB for 13 h before back-dilution into 100 ml K10T-1 medium to obtain an OD600 of 0.05. Subcultured strains were grown for 6 h with shaking at 30°C, and this was followed by determination of the OD600. For the wild type, 40 ml of culture (OD600, ∼0.85) was pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 3 min (25°C). An equivalent amount of cell biomass was processed for the apaH mutant by adjusting the volume of cells pelleted based on normalization using OD600. Culture supernatants were discarded, and cell pellets resuspended in 250 μl of extraction buffer (methanol-acetonitrile-water [40:40:20] with 0.1 N formic acid) with vortexing. Extraction was carried out for 30 min at −20°C, and this was followed by transfer to a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube and centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The extraction buffer was separated from the pelleted cell debris and placed in a fresh tube on ice. The cell pellet was then resuspended in an additional 125 μl of extraction buffer and incubated at −20°C for 15 min. The cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The extraction buffer was aspirated and combined with the extract obtained previously. A final centrifugation step was performed to ensure that all cell debris was removed, before 100 μl was moved to a fresh tube and neutralized by addition of 4 μl of 15% (NH4)2HCO3. It is important to note that the metabolite levels were measured using pelleted cells; although measurements obtained in this way can be informative, in some cases they may be misleading due to metabolic events that occur during centrifugation. However, the findings presented here showed robust reproducibility for samples harvested in independent experiments.

The resulting extract was collected and analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with a Finnigan TSQ Quantum DiscoveryMax triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp., San Jose, CA) coupled with an LC-20AD high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD). The mass spectrometry parameters were as follows: spray voltage, 3,000 V; nitrogen as the sheath gas at a pressure of 30 lb/in2 and as the auxiliary gas at a pressure of 10 lb/in2; argon as the collision gas at a pressure of 1.5 mtorr; and capillary temperature, 325°C. Reversed-phase liquid chromatography separation was achieved using a Synergi Hydro-RP column (particle size, 4 μm; 150 by 2 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) with the ion-pairing agent tributylamine in buffer. Solvent A was 10 mM tributylamine plus 15 mM acetic acid in water-methanol (97:3). Solvent B was methanol. The gradient was as follows: time zero, 0% solvent B; 5 min, 0% solvent B; 10 min, 20% solvent B; 20 min, 20% solvent B; 35 min, 65% solvent B; 38 min, 95% solvent B; 42 min, 95% solvent B; 43 min, 0% solvent B; and 50 min, 0% solvent B. The running time for each sample was 50 min. Other liquid chromatography parameters were as follows: autosampler temperature, 4°C; column temperature, 25°C; injection volume, 20 μl; and solvent flow rate, 200 μl/min.

Nucleotide compounds, including ADP, ATP, CTP, UTP, GTP, c-di-GMP, and AppppA, were detected by using selected reaction monitoring (SRM) in negative ionization mode. The scan time for each SRM analysis was 0.1 s, and the scan width was 1 m/z. The LC-MS/MS parameters, including the retention time (RT), were as follows: for ADP, SRM at m/z 426 → 159 at 25 eV and an RT of 32 min; for ATP, SRM at m/z 506 → 159 at 28 eV and an RT of 34.6 min; for CTP, SRM at m/z 482 → 384 at 22 eV and an RT of 34 min; for UTP, SRM at m/z 483 → 159 at 33 eV and an RT of 34.3 min; for GTP, SRM at m/z 522 → 424 at 23 eV and an RT of 34.3 min; for c-di-GMP, SRM at m/z 689 → 344 at 32 eV and an RT of 32.1 min; and for AppppA, SRM at m/z 835 → 488 at 31 eV and an RT of 36.2 min. The signal for each compound in biological samples was defined as the observed peak area on the corresponding chromatography trace.

Miscellaneous assays.

Qualitative and quantitative fluorescent phosphatase assays were carried out as previously described (25). The biofilm assay and the LapA localization assays were performed as described previously (24). Motility assays were also performed as described previously (7), as were c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity assays (24).

Heat sensitivity.

Mid-exponential-phase cultures grown in LB were normalized to obtain an OD600 of 0.5, and 500 μl of each culture was dispensed into a microcentrifuge tube. Normalized cultures were placed in a 50°C heating block with the lid open, and 10-μl samples were removed every 30 s for 3 min. Serial dilutions were prepared, and the appropriate dilutions were plated on LB to determine the number of CFU for each strain and treatment. The average number of CFU and standard error were calculated using three independent replicates.

Oxidative stress response.

Stationary-phase cultures (in LB) were back-diluted 1:100 and grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600, ∼ 0.4) in K10T-1 (high-Pi) medium. Then the cultures were supplemented with 0.1 mM H2O2 and grown for 1 h before they were washed in 1× TSP salts and normalized to obtain an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4. Oxidative stress was initiated by mixing 250 μl of cells with 250 μl of a 20 mM solution of hydrogen peroxide (diluted from a stock solution in 1× TSP salts). Cells that were not exposed to H2O2 were used to calculate the initial titer. During the assay 10-μl aliquots were removed at 30-min intervals and mixed with 90 μl of 1× TSP salts containing 1 mg/ml catalase to neutralize the hydrogen peroxide. After 5 min of incubation at room temperature, each tube was placed on ice and used as the 10−1 dilution for quantification of CFU. After completion of the time course, serial dilutions were prepared and plated on LB to determine the number of CFU. Sensitivity to oxidative stress was determined by graphing the number of CFU as a function of time. A poor adaptive response during preconditioning resulted in a higher rate of killing when organisms were exposed to high levels of oxidant.

Growth analysis.

Growth curves were generated using a Victor X3 multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Strains were preconditioned by growth in K10T-1 medium for 24 h before normalization using OD600 and subsequent back-dilution in 200 μl of K10T-1 medium to obtain an initial OD600 of approximately 0.01. The optical density was determined every ∼30 min with intermittent shaking, and the evaporated water was replaced by injecting 5 μl water after every measurement. The temperature was maintained at 30°C for the course of the experiment. Data were extracted, background corrected, and averaged for the four replicates to generate growth curves for each strain. The growth rate was calculated by plotting ln OD600 over time (in hours) and fitting a linear regression line to the exponential phase of growth. The slope of this line equaled the maximal growth rate expressed in divisions per hour. Lag time was calculated by extrapolating the linear regression line until it intersected with the starting value of ln OD600 at time zero. The point where this occurred was the lag time for the strain, expressed in hours. If there had been no lag time, exponential growth would have started immediately, and the regression line would have passed through zero. The yield was calculated by determining the percentage of the final optical density obtained for the wild type. This was a relative measure rather than absolute quantification.

Cloning of the lapA gene.

To clone lapA, a suicide plasmid that contained the N-terminal region of lapA, including the ribosome binding site (RBS) sequence, was constructed. An EcoRI site was added at the C-terminal end of this fragment. This plasmid was a derivative of pMQ87 and was designated pMQ87-lapA.

pMQ87-lapA was integrated into the genome of a Pf0-1 strain that expresses a hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged LapA gene, generating a strain with an origin of replication for E. coli and a gentamicin resistance cassette upstream of a full-length copy of lapA. Importantly, lapA, oriV, and the Gm cassette are flanked by EcoRI sites, and there are no other internal EcoRI sites on the plasmid. Genomic DNA was prepared from this strain and digested with EcoRI. By ligating the EcoRI-digested DNA, a self-replicating, selectable, lapA-containing plasmid was produced. To recover this plasmid, the ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli Top10, and transformants were selected using gentamicin. Numerous transformants harboring a plasmid with restriction profiles consistent with predictions were recovered. Sequence analysis confirmed that the LapA N-terminal and C-terminal regions were present. This plasmid was designated pLapA.

For complementation studies the lapA gene was moved to a Pseudomonas replicating plasmid. To generate this construct, pLapA was digested with EcoRI and HindIII to release a 16-kb fragment containing the lapA ORF. This fragment was subcloned into pBBRMCS-2, which placed the lapA gene under control of the Plac promoter. The resulting plasmid was designated pBB-lapA. lapA mutants harboring pBB-lapA express a full-length LapA protein, which is capable of restoring biofilm formation in the lapA mutant.

Expression of lapA and lapEBC from heterologous promoters.

The Plac promoter was placed in front of the lapA coding region using an allelic replacement methodology. The allelic replacement vector pMQ-Plac-lapA was constructed in yeast using in vivo recombination and consists of the Plac promoter from pU18-Tn7T-Gm-LAC flanked by 1- to 1.5-kb regions with sequence homology to facilitate correct recombination in the P. fluorescens genome.

P. fluorescens with the HA-tagged lapA gene was transformed with pMQ-Plac-lapA, which is a suicide plasmid in Pseudomonas species. Integrants from the first recombination were verified by PCR, before they were subjected to sucrose selection to identify strains that had undergone a second recombination event. Strains containing the lac promoter in front of the lapA coding region were identified by PCR and confirmed by sequence analysis. Strains expressing lapA via the Plac promoter were biofilm proficient, even in the absence of an inducer (e.g., isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG]) since pseudomonads do not encode the repressor LacI.

lapEBC was overexpressed using pLapEBC, which was described in a previous paper (24). Briefly, the lapEBC genes are expressed under control of the PBAD promoter, so the expression level can be controlled by addition of 0.2% arabinose to the culture medium. This plasmid can complement mutations in lapE, lapB, and lapC (24).

Statistical analysis.

Student t tests were routinely used to directly compare means for two experimental treatments. Unless otherwise stated, two-tailed t tests were performed by assuming that there was equal variance. In cases where multiple comparisons were made using the same data set, a Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the level of alpha (α) to account for the increased family-wise error rate. Specifically, α was divided by the number of repeated measurements for the same data set, and the resulting value was used as the new statistical criterion for judging the validity of the null hypothesis.

RESULTS

Pfl_5137 is required for maximal expression of Pho-dependent phosphatase activities.

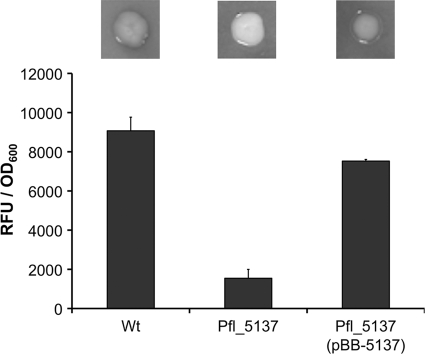

Previously, we identified a transposon insertion in the Pfl_5137 ORF (see Materials and Methods for information about gene nomenclature) that resulted in a qualitative defect in the ability to express phosphate monoesterase activity when an organism was grown in an inorganic phosphate (Pi)-limited medium (25). As part of this study we demonstrated that single-crossover disruption of the Pfl_5137 ORF resulted in phenotypes similar to those observed for the transposon mutant, and we utilized this strain background for subsequent experiments. In the first step to further characterize Pfl_5137, we quantified the phosphatase activity of a reconstructed Pfl_5137 mutant and compared it to the wild-type activity using a fluorescence-based assay. This assay showed that the Pfl_5137 mutant expressed ∼17% of the wild-type phosphatase activity when it was grown in Pi-limiting medium (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we could restore wild-type levels of phosphatase activity to the Pfl_5137 mutant by providing the Pfl_5137 ORF in trans. Together, these results suggest that loss of the Pfl_5137 gene and loss of its product are both necessary and sufficient for the substantial reductions in phosphatase activity that we observed.

FIG. 1.

Alkaline phosphatase activity assays. For the top panel, strains were grown on a low-Pi (K10Tπ) medium containing the chromogenic phosphatase substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP). The darkness of a colony indicates the relative phosphatase activity of the strain. For the bottom panel, phosphatase activity was quantified for each strain grown in low-Pi medium using fluorescent detection of substrate cleavage normalized to cell density and was expressed in relative fluorescence units (RFU)/OD600. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 4). Wt, wild type.

Pfl_5137 is a di-adenosine tetraphosphatase gene homologous to apaH.

Sequence analysis with the Basic Local Alignment and Search Tool (BLAST) indicated that the predicted protein product of Pfl_5137 is 49% identical to ApaH from E. coli. Analysis of E. coli identified ApaH as the major enzyme responsible for turnover of the nucleotide derivative di-adenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) (10). ApaH catalyzes symmetrical cleavage of Ap4A that results in two molecules of ADP. Loss of the ApaH function results in an approximately a 100-fold increase in the steady-state level of Ap4A in the E. coli cell (10, 19). We sought to test whether Pfl_5137 was indeed a homologue of apaH with conserved functions in P. fluorescens.

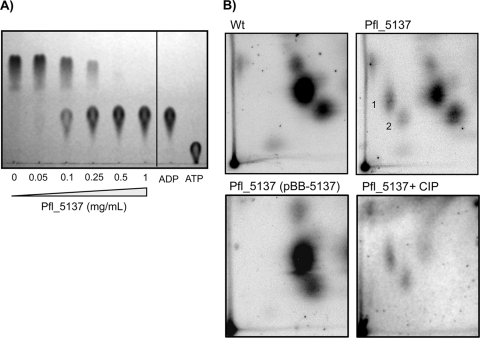

First, we analyzed the ability of Pfl_5137 to cleave Ap4A in vitro. For this assay, an N-terminal His-tagged derivative of Pfl_5137 was purified by metal affinity chromatography to a relative homogeneity of ∼85%. Enzymatic assays were performed using commercially available Ap4A as the substrate, followed by separation and detection of nucleotide species by one-dimensional TLC (1D-TLC). Like a di-adenosine tetraphosphatase, the Pfl_5137 protein converted Ap4A into two molecules of ADP in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

The Pfl_5137 protein is a di-adenosine tetraphosphatase. (A) In vitro reactions to assess enzymatic cleavage of di-adenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) were performed with different concentrations of purified Pfl_5137 protein and commercially available Ap4A as the substrate. Reaction products were separated and visualized by 1D-TLC, and the standards included were ATP and ADP. Purified ApaH protein was shown to cleave Ap4A in a dose-dependent fashion. Cleavage was symmetrical, producing ADP as the sole cleavage product. (B) In vivo analysis of Ap4A concentrations. Cells were grown in Pi-limiting medium for 6 h before they were labeled with sodium dihydrogen [32P]orthophosphate, which was followed by acid extraction. Shown are autoradiographs of whole-cell acid extracts separated by 2D-TLC. The preparations analyzed were the wild-type strain (Wt), the Pfl_5137 mutant, the Pfl_5137 mutant complemented in trans with pBB-5137, and Pfl_5137 mutant extract treated with calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) to cleave phosphate monoester bonds. The numbers indicate the reported locations of Ap4A (spot 1) and Ap4G (spot 2).

Second, we assessed the in vivo levels of Ap4A in the Pfl_5137 mutant and compared these levels with the wild-type levels. To do this, cells were grown for 6 h in a Pi-limiting medium before whole-cell labeling with sodium dihydrogen [32P]orthophosphate was performed. Ap4A was visualized by resolving whole-cell acid extracts by a 2D-TLC method specifically optimized for detection of Ap4A and similar dinucleotides (22). Using this analysis, the Pfl_5137 mutant was shown to have substantially elevated levels of nucleotide species that corresponded to Ap4A and di-guanosine tetraphosphate (Ap4G), based on previously established migration profiles (Fig. 2B). An elevated level of Ap4G is consistent with the known substrate specificity of ApaH, which can cleave any member of the Ap4N family (13). Both Ap4A and Ap4G were undetectable in wild-type extracts, which agrees with previous reports indicating that the basal level of Ap4A is typically <2 to 3 μM for E. coli (5, 22). Complementation of the Pfl_5137 mutant in trans was shown to restore the wild-type nucleotide profile, supporting the conclusion that the product of the Pfl_5137 gene is required for degradation of Ap4A and Ap4G.

Finally, we confirmed that the nucleotide species identified as Ap4A and Ap4G are resistant to cleavage by calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP). CIP cleaves phosphate monoester bonds found in nucleotide triphosphates, but it cannot cleave phosphodiester bonds present in Ap4A or Ap4G. As predicted, treatment of the Pfl_5137 extract with CIP cleaved most other phosphorylated species but did not cleave at the two spots that we identified as Ap4A and Ap4G locations. Based on these two independent experiments, we concluded that Pfl_5137 is a functionally conserved homologue of apaH, and we use this designation below.

Pleiotropic effects of mutations in apaH.

In E. coli, mutations in apaH and the associated increases in the level of Ap4A have a broad range of phenotypic consequences. For example, E. coli apaH mutants are nonmotile, are more sensitive to heat or oxidative stress, and are defective for catabolite repression and timing of cell division (10, 28). Although the product of the P. fluorescens apaH homologue has enzymatic activities similar to those of the E. coli protein, we wanted to assess the degree to which the apaH mutant phenotypes are also conserved.

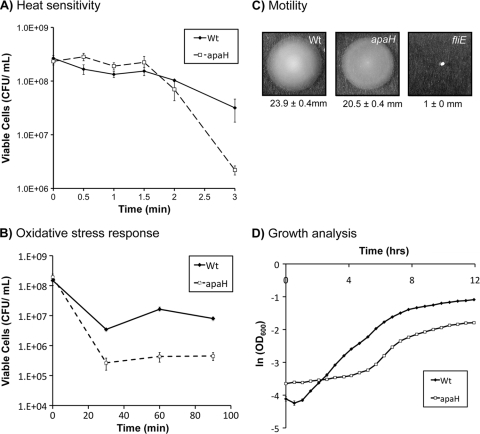

Similar to findings for E. coli, the P. fluorescens apaH mutant was more sensitive to heat shock (Fig. 3 A) and oxidative stress (Fig. 3B). In contrast to findings for E. coli, we detected no defect in flagellum-mediated motility (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, although the apaH mutant had a maximal growth rate very similar to that of the wild type (wild type, 0.506 h−1; apaH mutant, 0.511 h−1), the apaH mutant had a longer lag time (wild type, 1.0 h; apaH mutant, 4.6 h), as well as a substantially decreased yield (48% of the wild-type yield based on the final optical density). The lag time of the apaH mutant can be reduced to a value similar to the wild-type value by reducing the time spent in stationary phase before back-dilution in fresh medium (data not shown). This property of the apaH mutant was utilized to better synchronize cultures used for phenotypic analyses throughout this study. The effect of the apaH mutation on catabolite repression was not assessed.

FIG. 3.

Conservation of known apaH mutant phenotypes in P. fluorescens. (A) Heat sensitivity. The wild-type (Wt) and apaH strains were challenged with a 50°C heat shock. Samples were recovered every 30 s, and plate counting was performed to ascertain the number of CFU. (B) Oxidative stress response. The wild type and the apaH mutant were challenged with 10 mM H2O2 for the times indicated, aliquots were recovered and neutralized, and plate counting was performed to ascertain the number of CFU. (C) Flagellum-mediated swimming. The wild type and the apaH mutant were inoculated onto 0.3% high-Pi (K10T-1) agar, and their abilities to swim away from the inoculation point were assessed. Swim diameters (mean ± standard error; n = 10) are indicated below the images. (D) Growth analysis. The optical density at 600 nm was measured for cultures of both the wild type and the apaH mutant during growth in high-Pi (K10T-1) medium. The natural log of OD600 was plotted against time. The growth rate, lag time, and yield were calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

It appears that, similar to findings for E. coli, mutations in apaH are also pleiotropic in P. fluorescens; however, the exact phenotypes affected by perturbations in Ap4A metabolism are not entirely conserved. This is underscored by the fact that a P. fluorescens apaH mutant is also defective for siderophore synthesis, a novel phenotype associated with Ap4A metabolism (25).

Genomic context of apaH in P. fluorescens.

In E. coli apaH is the last gene in an operon with ksgA and apaG. Promoters have been mapped upstream of ksgA (producing a polycistronic message including ksgA and apaGH) and upstream of apaG (producing a polycistronic message including apaGH) (3, 32). Homologues of apaG (52% identity) and ksgA (47% identity) are present in P. fluorescens and have the same genomic organization relative to apaH. ksgA encodes a dimethyadenosine transferase involved in RNA editing and ribosome function (23), whereas apaG is a gene whose function is unknown. In contrast to E. coli apaH, P. fluorescens apaH is followed by a gene annotated glpE, which is predicted to encode a thiosulfate sulfur transferase with no known biological role (31). We do not have experimental evidence for the operon structure of this region in P. fluorescens; however, the Database for prOkaryotic OpeRons (DOOR; http://csbl1.bmb.uga.edu/OperonDB/) predicts that apaG, apaH, and glpE form an operon.

apaH is required for efficient Pho regulon induction in Pi-limiting conditions.

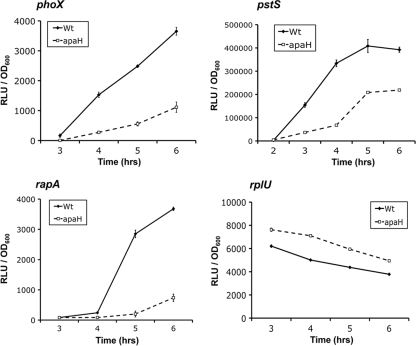

We originally isolated the apaH mutant during an effort to identify regulatory inputs of the Pho system that are distinct from those of phosphate metabolism. We utilized Pho-regulated phosphatase activity as a reporter to screen for the effect of mutations on Pho regulon activation. Because phosphatase activity is an indirect measure of Pho regulon activity, it was possible that mutations were recovered as a result of more specific perturbations to phosphatase activity rather than broad inhibition of Pho regulon expression. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we assessed transcriptional activation of a range of Pho regulon promoters in response to a Pi-limiting environment (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

apaH mutation inhibits Pho regulon expression. Transcriptional fusions coupling the promoters of phoX, pstS, rapA, and rplU to luciferase expression were constructed. Luciferase activity was recorded over time for each fusion in the wild-type (Wt) and apaH backgrounds during growth in low-Pi (K10Tπ) medium. The results are expressed in relative light units (RLU) normalized to the optical density of the culture at the time of analysis. The rate of the increase in light production is an indirect measure of transcriptional induction from a specific promoter. The phoX, rapA, and pstS genes are known members of the Pho regulon. The rplU transcriptional fusion was used as a Pho-independent control.

We constructed luciferase transcriptional fusions to three known Pho genes, phoX, pstS, and rapA, as well as one Pho-independent gene, rplU. PhoX is the enzyme that is primarily responsible for Pho-dependent phosphatase activity (25). PstS is a component of a high-affinity Pi transporter and is also required for efficient repression of the Pho regulon in Pi-replete environments (26, 38). RapA is a phosphodiesterase involved in c-di-GMP metabolism (24). In contrast to PhoX, neither PstS nor RapA enzymatically contributes to the Pho-dependent phosphatase activity of P. fluorescens.

Expression of these fusions was monitored over time for the wild type and the apaH mutant during growth in Pi-limiting media. This analysis clearly indicated that the apaH mutation results in defects in transcriptional activation of all three Pho genes during Pi limitation (Fig. 4). Although induction of the Pho regulon occurred at around the same time for both the mutant and the wild type, the rate of transcription subsequent to induction was much lower for the apaH mutant. These data support the conclusion that the apaH mutation results in broad inhibition of Pho regulon induction rather than having an isolated effect on the expression of Pho-dependent phosphatases. Furthermore, we did not detect similar perturbations in rplU transcription, which argues against the hypothesis that there is a nonspecific reduction in transcription of all genes in the apaH background.

apaH impacts biofilm formation via Pho-dependent and Pho-independent pathways.

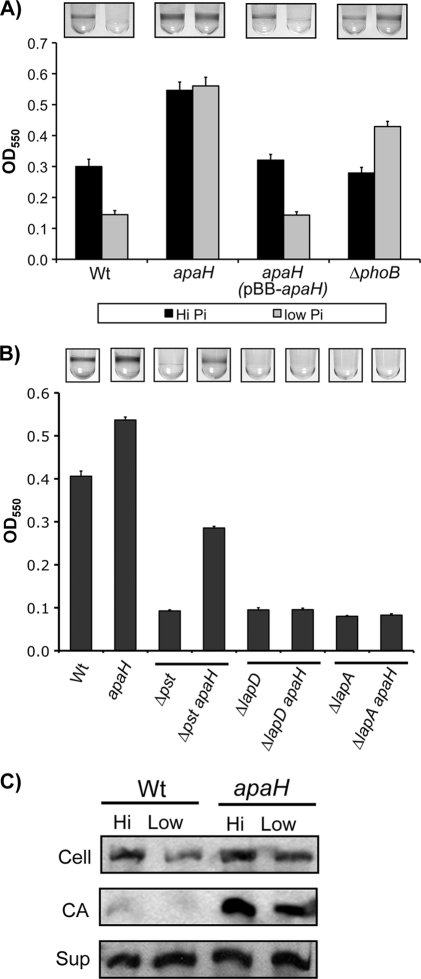

Previously, we have shown that inhibition of P. fluorescens biofilm formation in low-Pi environments requires Pho regulon-dependent activation of rapA (24). Since an apaH mutant exhibits a lower rate of rapA induction in Pho-activating conditions, we reasoned that loss of biofilm formation should also be suppressed in the apaH background. As a test of this hypothesis, we compared biofilm formation by the apaH mutant with biofilm formation by the wild type when grown in both Pi-sufficient and Pi-limiting media (Fig. 5A). As controls, we also included the apaH mutant expressing a wild-type copy of apaH in trans and the phoB mutant. Consistent with inhibition of rapA induction, apaH strains did not show a reduction in biofilm formation upon Pi starvation, whereas the wild-type biofilm formation was significantly reduced. Complementation of the apaH mutation restored the wild-type biofilm phenotype.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of biofilm formation by the apaH mutant. (A) Biofilm formation by the apaH mutant was assessed by comparison to biofilm formation by the wild type (Wt) for organisms grown in both high- and low-Pi conditions after incubation for 10 h. The biofilm phenotypes of the apaH strain were complemented by providing a wild-type copy of apaH on a plasmid (pBB-apaH). The phoB mutant was used as a positive control because it is unable to express the Pho regulon and forms biofilms regardless of the Pi concentration. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 10). (B) The apaH allele was tested to determine its ability to rescue the biofilm defects of strains with null mutations in pst, lapD, and lapA. Strains were grown in high-Pi conditions for 6 h before attached bacteria were stained. The Δpst apaH strain showed partial rescue of biofilm formation compared to the pst single mutant. The ΔlapA apaH and ΔlapD apaH strains did not show increases in biofilm formation compared to the lapA and lapD single mutants, respectively. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 10). (C) The apaH mutation results in accumulation of LapA at the cell surface: Western blot detection of LapA-HA for whole-cell (Cell), cell surface-associated (CA), and supernatant (Sup) fractions prepared from both the wild type and the apaH mutant grown in both high- and low-Pi-conditions.

As a further test of the relationship between apaH and Pho-dependent effects on biofilm formation, we assessed the ability of the apaH allele to rescue biofilm formation by a pst mutant. Mutation of pst results in constitutive Pho regulon activation, irrespective of the Pi concentration in the environment. Accordingly, pst mutants are severely defective for biofilm formation, even in high-Pi conditions. When apaH was mutated in the pst background, we observed partial restoration of biofilm formation, which is consistent with the delay in Pho regulon activation caused by the apaH allele (Fig. 5B).

We also tested the ability of the apaH allele to rescue biofilm formation by a lapD mutant and a lapA mutant. LapA is a large adhesin that is required for stable surface attachment by P. fluorescens (17). Mutations in lapA prevent synthesis of the adhesin, whereas mutations in lapD inhibit localization of LapA to the cell surface (27). Both types of mutants have severe biofilm defects. In this analysis, we observed that an apaH mutation was not capable of restoring biofilm formation to either a lapD strain or a lapA strain, indicating that the ability of apaH mutations to enhance biofilm formation requires a functional Lap system (Fig. 5B). These data agree with previous studies which showed that lap mutations map genetically downstream of mutations in rapA.

In addition to providing support for a Pho-dependent affect on biofilm formation, the analysis described above also indicated that the apaH allele has a more general Pho-independent effect on biofilm formation. This was inferred from the fact that the apaH mutant formed approximately 2-fold more biofilm than the wild type formed when grown in Pi-replete conditions (Fig. 5A). In this environment the Pho regulon was not expressed, so the effect of the apaH allele on rapA would not have contributed to the biofilm phenotype observed.

Consequences of the apaH mutation for the Lap system.

The degree to which LapA is secreted and localized to the outer membrane plays a large role in determining whether P. fluorescens transitions to a committed interaction with a surface (24). Given the central role of LapA in biofilm formation and genetic data showing that apaH biofilm stimulation is dependent on a functional Lap system, we investigated whether mutations in apaH affect LapA production and/or localization to the outer membrane.

For the wild type and the apaH mutant we measured the relative levels of three different types of LapA: whole-cell (Cell), cell surface-associated (CA), and supernatant (Sup) LapA. In general, the quantity of CA LapA correlated well with the ability of P. fluorescens to form a biofilm; the less CA LapA, the smaller the amount of biofilm formed (24, 27). In this analysis we observed that higher levels of LapA were associated with the cell surface in the apaH mutant than in the wild type (Fig. 5C). Importantly, this was the case in both high- and low-Pi conditions, which is consistent with the biofilm phenotypes of the apaH mutant. We did not observe any major changes in the amounts of LapA in either the whole-cell or supernatant fractions of the apaH mutant and the wild type in either high- or low-Pi conditions (Fig. 5C).

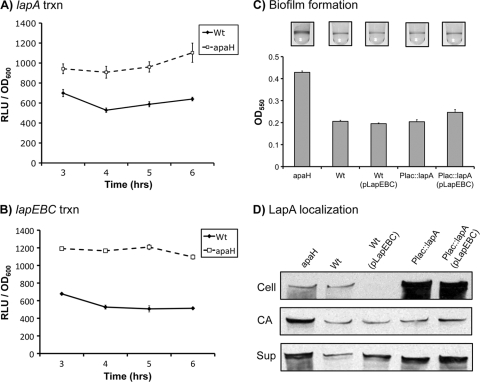

In addition to investigating the effects on LapA secretion, we also assessed whether apaH mutations affect transcription of lapA and the transporter-encoding operon lapEBC. In this analysis we utilized luciferase transcriptional fusions to obtain a relative measure of lapA and lapEBC transcription in the wild-type strain and the apaH mutant (Fig. 6A and B). This analysis showed that loss of apaH resulted in approximately 2-fold increases in the levels of both lapA and lapEBC transcription in multiple phases of growth. These findings prompted us to ask whether increases in LapA and/or LapEBC expression are sufficient to explain the increase in LapA secretion and biofilm formation by the apaH mutant.

FIG. 6.

Increased lapA and lapEBC transcription does not explain increased biofilm formation by the apaH mutant. (A and B) Effects of the apaH mutation on lapA transcription (trxn) (A) and lapEBC transcription (B). Luciferase fusions were constructed for the lapA and lapEBC promoters and integrated into the native chromosomal location to generate a merodiploid. Luciferase activity was measured over time for strains grown in high-Pi (K10T-1) medium. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 3). RLU, relative light units; Wt, wild type. (C) Effect of expression of lapA and lapEBC from heterologous promoters on biofilm formation. Biofilms were incubated for 8 h before visualization by crystal violet staining. Levels of biofilm formation are shown. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 10). (D) Effect of expression of lapA and lapEBC from heterologous promoters on LapA secretion and localization: Western blot detection of LapA-HA for whole-cell (Cell), cell surface-associated (CA), and supernatant (Sup) fractions prepared from both the wild type and the apaH mutant grown in high-Pi conditions.

We constructed strains in which transcription of lapA and lapEBC were placed under control of the heterologous promoters Plac and PBAD, respectively. We then quantified the effect on biofilm formation when lapA and lapEBC were expressed from these heterologous promoters independent of each other or simultaneously in the same cell. We observed that expression of either lapA or lapEBC by itself was not sufficient to enhance biofilm formation by P. fluorescens (Fig. 6C). Expression of lapEBC in conjunction with lapA from these heterologous promoters resulted in a small increase in biofilm formation, but the increase was not comparable to the 2-fold increase exhibited by the apaH mutant (Fig. 6C).

LapA secretion and localization were also assessed for strains expressing lapA and lapEBC from the same heterologous promoters used for the studies whose results are shown in Fig. 6C. Consistent with the biofilm phenotypes, strains expressing either lapA or lapEBC showed little change in the CA LapA level compared to the wild type (Fig. 6D). This was the case despite the marked increase in LapA synthesis in the Plac::lapA strain and increased export in the wild-type (pLapEBC) strain, as shown by loss of LapA from the Cell LapA fraction (Fig. 6D). In cells expressing both lapA and lapEBC from the heterologous promoters, there was evidence of a small increase in the CA LapA level, which is consistent with the small increase in biofilm formation that we observed. In contrast to the levels of CA LapA, the levels of supernatant LapA increased substantially compared to the wild-type levels when either the transporter (LapEBC) or the adhesin (LapA) was overexpressed (Fig. 6D). This result suggests that although more LapA was exported, it was not efficiently retained at the cell surface and therefore did not contribute to biofilm formation.

Collectively, these data suggest that the increases in lap gene expression associated with loss of ApaH function are not sufficient by themselves to explain the increased localization of LapA to the outer membrane and the increased biofilm formation by the apaH mutant.

Effect of apaH mutations on c-di-GMP metabolism.

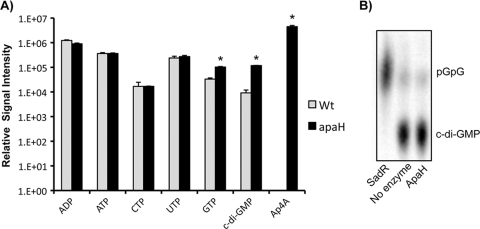

c-di-GMP is recognized as an important intracellular signaling molecule in many bacterial species (33). In P. fluorescens high levels of c-di-GMP enhance biofilm formation by promoting secretion and localization of LapA to the outer membrane (24, 27). Given that overexpression of the lap system was not sufficient to explain the apaH-dependent effects on biofilm formation in high-phosphate medium, we wondered whether c-di-GMP levels were increased as a consequence of disruptions in Ap4A metabolism. To examine this possibility, we determined c-di-GMP levels for the apaH mutant and the wild type. In addition, we also determined the levels of Ap4A and a range of other nucleosides.

Whole-cell acid extracts were prepared in triplicate for the wild type and the apaH mutant grown in high-Pi (K10T-1) medium. The levels of c-di-GMP, Ap4A, ATP, GTP, UTP, and CTP were measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, and the statistical significance of differences was analyzed using two-tailed t tests corrected for multiple comparisons. In agreement with our analysis described above (Fig. 2), the levels of Ap4A in the apaH mutant background increased at least 6 orders of magnitude (P < 0.00098, t = 8.65, df = 4). In this analysis we also observed that the levels of c-di-GMP were on the order of 10-fold higher in the apaH mutant than in the wild type (P = 0.0000045, t = 33.8 df = 4) (Fig. 7A). For only one of the remaining nucleoside triphosphates, GTP, was there a significant difference in the mean levels after correction for multiple tests; the levels for the apaH mutant were 3-fold higher than the levels for the wild type (P = 0.00058, t = 9.92, df = 4).

FIG. 7.

Effect of the apaH mutation on nucleotide pools. (A) Analysis of nucleotide pools by mass spectrometry. Wild-type (Wt) and apaH mutant cultures were grown in triplicate for 5 to 6 h in high-Pi (K10T-1) medium before extraction of nucleotides and relative quantification by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Extracts were analyzed to determine the levels of ADP, ATP, CTP, UTP, GTP, c-di-GMP, and Ap4A. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 3). For statistical inference with Student's t tests, alpha (α) was set at 0.0071 after adjustment for multiple comparisons using a Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05/7). Statistically significant differences are indicated by an asterisk. Ap4A could not be detected in wild-type extracts. Using this assay, the limit of detection for Ap4A is ∼20 ng/ml. (B) Assay for c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase activity. Purified ApaH (5 mg/ml) was unable to cleave c-di-GMP. SadR was used as a positive control for PDE activity, which completely cleaved c-di-GMP to generate pGpG.

ApaH cannot cleave c-di-GMP.

One possible explanation for the apaH-dependent increase in the level of c-di-GMP is that ApaH is also able to cleave c-di-GMP. ApaH cleaves phosphodiester bonds, which is the same activity utilized by EAL domain-containing proteins for cleavage of c-di-GMP. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the ability of purified His-tagged ApaH to cleave c-di-GMP in vitro. We observed no phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity against the c-di-GMP substrate using concentrations of ApaH well in excess of the concentration needed for effective cleavage of Ap4A (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the results for our positive control (SadR) showed that there was complete cleavage of c-di-GMP in our assays. These results suggest that it is changes in Ap4A metabolism that impact c-di-GMP biosynthesis, not simply the fact that ApaH acts directly to modify levels of c-di-GMP.

Purine metabolism impacts c-di-GMP levels and biofilm formation by the apaH mutant.

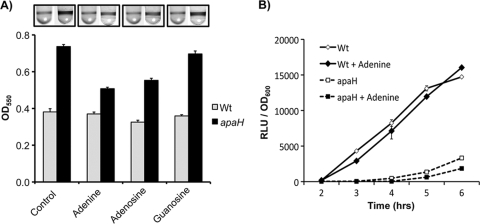

The high levels of Ap4A in the apaH mutant are likely to constitute a significant fraction of total cellular adenosine nucleotides, which could impact overall purine synthesis. These observations, together with the higher levels of GTP seen in the apaH mutant, suggested that purine biosynthesis might be upregulated as a consequence of inhibition of Ap4A recycling. An extension of this logic is that increases in purine metabolism and concomitant increases in the level of GTP may result in increases in the level of c-di-GMP in the apaH mutant. We sought to test this hypothesis by assessing whether exogenous addition of purine bases and/or nucleosides could reduce c-di-GMP levels and suppress the enhanced biofilm formation by the apaH mutant.

Before conducting this experiment, we first confirmed that P. fluorescens Pf0-1 is capable of utilizing exogenous bases and nucleosides by showing that both adenine and adenosine can rescue the growth of a purF and purD mutant (data not shown). We next assessed biofilm formation by the apaH mutant and wild type with and without addition of 1 mM adenine, adenosine, or guanosine. Consistent with our hypothesis, both adenine and adenosine partially suppressed the enhanced biofilm formation by the apaH mutant (Fig. 8A). Importantly, similar treatment of the wild type did not impact the normal biofilm formation process. Furthermore, the effect of adenine and adenosine was specific, as addition of guanosine did not suppress the apaH mutant biofilm phenotype. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that disruptions in Ap4A recycling result in a decrease in the level of ADP and that the cell responds by increasing the flux through de novo purine biosynthetic pathways.

FIG. 8.

Purine metabolism and apaH mutant phenotypes. (A) Supplementation of biofilm formation assay mixtures with exogenous adenine, adenosine, and guanosine to a final concentration of 1 mM. Biofilm assay mixtures were incubated for 8 h before visualization by crystal violet staining. The levels of biofilm formation are shown. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 10). (B) Effect of addition of adenine on Pho regulon activation. The wild type and the apaH mutant expressing the phoX luciferase promoter fusion were monitored for Pho activation during growth in low-Pi (K10Tπ) medium. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 3). RLU, relative light units; Wt, wild type.

To further test our model, we determined the levels of c-di-GMP and GTP in the apaH mutant both with and without addition of 1 mM adenine. Based on the ability of adenine to partially suppress the apaH mutant's biofilm phenotype, we hypothesized that treatment with adenine should reduce c-di-GMP and GTP levels. In agreement with this prediction, our analysis indicated that there was a 36% decrease in the relative level of c-di-GMP after treatment with 1 mM adenine (apaH mutant, 1.1 × 105 ± 1.2 × 104; apaH mutant with adenine, 7.3 × 104 ± 4.4 × 103) and a 30% decrease in the relative GTP levels (apaH mutant, 1.8 × 105 ± 6.1 × 104; apaH mutant with adenine, 1.3 × 105 ± 3.4 × 104). However, only the decrease in the level of c-di-GMP was statistically significant when the data were analyzed with a one-tailed t test corrected for multiple comparisons (for c-di-GMP, P = 0.019, t = 3.04, and df = 4; for GTP, P = 0.24, t = 0.779, and df = 4 [α = 0.025]). The reduction in the c-di-GMP level represents only partial rescue of the apaH phenotype, for which the level of c-di-GMP was 10-fold higher than the wild-type level (Fig. 7). Thus, addition of adenine partially rescued both the increased levels of c-di-GMP and the increased biofilm formation phenotype observed for the apaH mutant.

Lastly, addition of adenine to the apaH mutant did not restore wild-type growth dynamics. In fact, we detected no difference between the growth of the apaH mutant with adenine added to the culture medium and the growth of the apaH mutant without adenine added to the culture medium (data not shown).

Purine metabolism and Pho regulon expression.

Based on our finding that purine metabolism can impact c-di-GMP levels and biofilm formation, we decided to investigate whether the defects in Pho regulon expression observed for the apaH mutant could also be explained by perturbations in purine metabolism. To do this, we measured phoX transcription in the apaH and wild-type backgrounds when organisms were grown in low-Pi media both with and without 1 mM adenine (Fig. 8B). This analysis indicated that addition of adenine did not affect the rate of Pho induction in the apaH mutant. In fact, Pho induction was delayed slightly due to the adenine treatment, most likely because of Pi impurities in the adenine stock solution. Regardless, it is clear that addition of exogenous adenine cannot suppress the Pho regulon induction defect exhibited by the apaH mutant. Therefore, while addition of adenine partially rescued the increased biofilm formation and c-di-GMP levels observed for the apaH mutant, changes in purine metabolism were unlikely to account for the altered induction of the Pho regulon or the growth defect of this mutant.

DISCUSSION

Di-adenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) metabolism is ubiquitous in nature, yet its biological roles are still poorly understood. In this study, we explored a novel role for Ap4A metabolism in transcriptional control of Pho regulon expression and regulation of biofilm formation by P. fluorescens. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that Ap4A metabolism has a role as an intracellular regulator; however, they also support the hypothesis that perturbations in Ap4A metabolism can impact global cellular traits, such as biofilm formation, through more general disruption of purine-based nucleotide dynamics.

We rigorously demonstrated that Pfl_5137 of P. fluorescens Pf0-1 encodes a di-nucleotide tetraphosphatase similar to ApaH from E. coli. Loss of apaH resulted in accumulation of high levels of di-adenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) and was phenotypically pleiotropic.

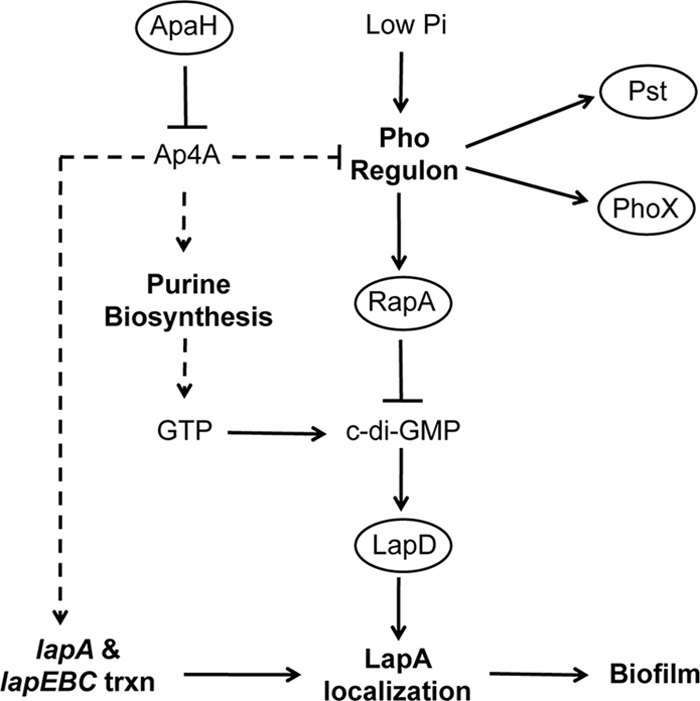

In the current work we focused on substantiating the relationship between Ap4A metabolism and its novel regulation of P. fluorescens biofilm formation. Ap4A metabolism affects biofilm formation via two separate yet related pathways. First, high levels of Ap4A due to mutation of apaH prevent loss of biofilm formation in response to low levels of extracellular Pi. In the wild type, activation of the Pho regulon in low-Pi environments results in expression of a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, RapA (24). Subsequent RapA-mediated reductions in the c-di-GMP concentration inhibit secretion and localization of the adhesin LapA to the outer membrane. LapA is required for proper colonization of surfaces and subsequent biofilm formation. An apaH mutant circumvents this regulatory response to low Pi by preventing efficient activation of the Pho regulon. We do not yet know the mechanism by which the level of Ap4A impacts Pho regulon activation (Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

Summary of the current model for the role of ApaH in biofilm formation by P. fluorescens. Loss of the ApaH function and subsequent accumulation of Ap4A promote biofilm formation by two mechanisms. (i) Accumulation of Ap4A prevents efficient recycling of ADP, which in turn promotes de novo purine biosynthesis. This leads to increased levels of GTP and subsequent increases in the levels of c-di-GMP through the action of diguanylate cyclases. Higher levels of c-di-GMP result in increased biofilm formation by promoting localization of the adhesin LapA to the cell surface via LapD. Ap4A also promotes expression of LapA and its transporter, LapEBC, which in conjunction with increases in the level of c-di-GMP, contribute to increased biofilm formation. (ii) In low-Pi environments biofilm formation is inhibited through expression of RapA, a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase that is a member of the Pho regulon. High levels of Ap4A inhibit activation of the Pho regulon and suppress the loss of biofilm formation. Ellipses indicate a protein, bold type indicates a biological process, and normal type indicates a small molecule. Solid arrows indicate that there is experimental evidence for direct interactions, whereas dashed lines indicate interactions that may be either direct or indirect.

A second, more general mechanism by which Ap4A metabolism affects biofilm formation was also observed. In Pi-replete conditions, when Pho regulon expression was repressed, we observed that the apaH mutant produced approximately 2-fold more biofilm than the wild type produced. The increased propensity for surface attachment is explained by substantial increases in the amount of LapA attached to the outer membrane and the concurrent increases in the level of intracellular c-di-GMP.

In both cases, Ap4A modulates biofilm formation by altering the concentration of c-di-GMP. In low-Pi conditions this connection is mediated through the Pho regulon and RapA; however, mechanisms connecting increases in the Ap4A level with Pho-independent increases in the c-di-GMP level are less obvious. One possibility that we have begun to explore is that imbalances in general nucleotide pools due to a block in Ap4A turnover result in changes in c-di-GMP pools in the cell. Whole-cell nucleotide analysis indicated that, in addition to increased c-di-GMP levels, GTP levels were elevated 3-fold in the apaH mutant. Furthermore, the ATP levels did not change even though large amounts of ADP were sequestered in the cell as Ap4A. Together, these observations raise the possibility that de novo purine biosynthetic pathways might be activated to a greater degree in the apaH mutant, resulting in higher GTP concentrations and more synthesis of c-di-GMP. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that addition of the purine adenine led to significant reductions in biofilm formation by the apaH mutant but had no effect on wild-type biofilm formation. Also consistent with our hypothesis, we observed a small (36%) yet statistically significant decrease in the c-di-GMP level when the apaH mutant was treated exogenously with adenine. Although addition of adenine could not fully restore wild-type biofilm dynamics or c-di-GMP profiles to the apaH mutant, the partial rescue of both phenotypes implies that perturbation of purine metabolism is an important component of the mechanisms connecting Ap4A metabolism to the c-di-GMP level and the regulation of biofilm formation by P. fluorescens. Nucleotide biosynthesis is a complicated biological process. Thus, a more in-depth analysis is required to understand exactly how Ap4A levels impact purine metabolism and to what extent the perturbations explain increases in c-di-GMP levels and biofilm formation in Pi-replete conditions.

The current view is that c-di-GMP levels are tightly controlled through the opposing actions of diguanylate cyclase (DGC) and PDE domain-containing proteins (34, 35), and the regulation of PDE and DGC activity, rather than substrate availability, is considered a major control point for fine-tuning c-di-GMP levels. In contrast to this view, our data suggest that the level of c-di-GMP may also reflect the general metabolic status of the cell and respond to changes in the flux of nucleotides and their precursors. We feel that our results provide an important reminder that although c-di-GMP acts as a signaling molecule, its biosynthesis is intimately connected to the core metabolic networks of the cell and therefore must be understood in this context.

In these studies we demonstrated that overexpression of the adhesin LapA or the transporter LapEBC was not sufficient to appreciably increase biofilm formation by the wild type. Interestingly, overexpression of both the adhesin and its transporter allowed export of large quantities of LapA from the cytoplasm but resulted in only small increases in the CA LapA level and biofilm formation. These findings confirmed that increases in transcription of lapA and lapEBC were not sufficient to explain the increased biofilm formation by the apaH mutant. In addition to answering a specific question, these results reinforce the critical role of posttranslational regulation in mediating efficient localization of LapA to the cell surface. A strong candidate for mediating such interactions is c-di-GMP, especially considering a recent report that identified LapD as a c-di-GMP receptor protein that regulates localization of LapA to the outer membrane (27). We hypothesize that increases in lapA and lapEBC expression, like those seen in the apaH mutant, can contribute to upregulation of biofilm formation, but only when they are accompanied by activation of c-di-GMP-dependent pathways that facilitate localization of LapA to the cell surface.

The studies that we describe here utilized a mutation in apaH to increase the levels of Ap4A in the cell. Ultimately, we would like to know whether physiological conditions can promote increases in the Ap4A concentration that are sufficient to impact regulation of biofilm formation. Studies of E. coli have shown that treatment with a range of oxidizing agents or a heat shock can stimulate production of Ap4A so that the levels in the cell are comparable to those seen in an apaH mutant (5). These studies formed the basis of the hypothesis that Ap4A is an alarmone that regulates cellular responses to stress resulting from oxidation or temperature. In contrast to results obtained with E. coli, we did not detect increases in Ap4A levels when P. fluorescens wild-type cells were treated with the oxidizing agent hydrogen peroxide (data not shown). Further studies are required to rigorously determine what physiological conditions promote Ap4A formation in P. fluorescens and how these conditions affect c-di-GMP levels and biofilm formation.

The biological effects of disruptions in Ap4A metabolism are complicated and diverse, and such effects have been found in different species, phyla, and domains. It is clear that a greater understanding of the mechanism is required if we are to move beyond phenomenological descriptions of diverse functions ascribed to Ap4A and its related nucleotides. We believe that our work speaks to the more general concept that metabolic networks can play central roles in the regulation of complex cellular traits, rather than simply being confined to management of the energy and biosynthetic needs of the cell.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant MCB-9984521 to G.A.O., by National Institutes of Health predoctoral fellowship T32 GM08704 and the John H. Copenhaver, Jr., and William H. Thomas, M.D., 1952 Fellowship to P.D.N., and by National Science Foundation CAREER Award MCB-0643859 and National Institute of General Medical Sciences Center for Quantitative Biology/National Institutes of Health grant P50 GM-071508 to J.D.R.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, J. C., and M. K. Jacobson. 1986. Alteration of adenyl dinucleotide metabolism by environmental stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:2350-2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertani, G. 2004. Lysogeny at mid-twentieth century: P1, P2, and other experimental systems. J. Bacteriol. 186:595-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanchin-Roland, S., S. Blanquet, J. M. Schmitter, and G. Fayat. 1986. The gene for Escherichia coli diadenosine tetraphosphatase is located immediately clockwise to folA and forms an operon with ksgA. Mol. Gen. Genet. 205:515-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bochner, B. R., and B. N. Ames. 1982. Complete analysis of cellular nucleotides by two-dimensional thin layer chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 257:9759-9769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bochner, B. R., P. C. Lee, S. W. Wilson, C. W. Cutler, and B. N. Ames. 1984. AppppA and related adenylylated nucleotides are synthesized as a consequence of oxidation stress. Cell 37:225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brevet, A., J. Chen, F. Leveque, P. Plateau, and S. Blanquet. 1989. In vivo synthesis of adenylylated bis(5′-nucleosidyl) tetraphosphates (Ap4N) by Escherichia coli aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:8275-8279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caiazza, N. C., J. H. Merritt, K. M. Brothers, and G. A. O'Toole. 2007. Inverse regulation of biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189:3603-3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi, K. H., J. B. Gaynor, K. G. White, C. Lopez, C. M. Bosio, R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2:443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compeau, G. B., M. Kilstrup, K. Barilla, B. Jochimsen, and S. B. Levy. 1988. Survival of rifampin-resistant mutants of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida in soil systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:2432-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farr, S. B., D. N. Arnosti, M. J. Chamberlin, and B. N. Ames. 1989. An apaH mutation causes AppppA to accumulate and affects motility and catabolite repression in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:5010-5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guranowski, A. 2004. Metabolism of diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) and related nucleotides in plants; review with historical and general perspective. Front. Biosci. 9:1398-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guranowski, A. 2000. Specific and nonspecific enzymes involved in the catabolism of mononucleoside and dinucleoside polyphosphates. Pharmacol. Ther. 87:117-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guranowski, A., H. Jakubowski, and E. Holler. 1983. Catabolism of diadenosine 5′,5‴-P1,P4-tetraphosphate in procaryotes. Purification and properties of diadenosine 5′,5‴-P1,P4-tetraphosphate (symmetrical) pyrophosphohydrolase from Escherichia coli K12. J. Biol. Chem. 258:14784-14789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guranowski, A., E. Starzynska, A. G. McLennan, J. Baraniak, and W. J. Stec. 2003. Adenosine-5′-O-phosphorylated and adenosine-5′-O-phosphorothioylated polyols as strong inhibitors of (symmetrical) and (asymmetrical) dinucleoside tetraphosphatases. Biochem. J. 373:635-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen, S., K. Lewis, and M. Vulic. 2008. Role of global regulators and nucleotide metabolism in antibiotic tolerance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2718-2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinsa, S. M., M. Espinosa-Urgel, J. L. Ramos, and G. A. O'Toole. 2003. Transition from reversible to irreversible attachment during biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 requires an ABC transporter and a large secreted protein. Mol. Microbiol. 49:905-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ismail, T. M., C. A. Hart, and A. G. McLennan. 2003. Regulation of dinucleoside polyphosphate pools by the YgdP and ApaH hydrolases is essential for the ability of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to invade cultured mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:32602-32607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnstone, D. B., and S. B. Farr. 1991. AppppA binds to several proteins in Escherichia coli, including the heat shock and oxidative stress proteins DnaK, GroEL, E89, C45 and C40. EMBO J. 10:3897-3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kisselev, L. L., J. Justesen, A. D. Wolfson, and L. Y. Frolova. 1998. Diadenosine oligophosphates (Ap(n)A), a novel class of signalling molecules? FEBS Lett. 427:157-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, P. C., B. R. Bochner, and B. N. Ames. 1983. Diadenosine 5′,5‴-P1,P4-tetraphosphate and related adenylylated nucleotides in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 258:6827-6834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangat, C. S., and E. D. Brown. 2008. Ribosome biogenesis; the KsgA protein throws a methyl-mediated switch in ribosome assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 70:1051-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monds, R. D., P. D. Newell, R. H. Gross, and G. A. O'Toole. 2007. Phosphate-dependent modulation of c-di-GMP levels regulates Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 biofilm formation by controlling secretion of the adhesin LapA. Mol. Microbiol. 63:656-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monds, R. D., P. D. Newell, J. A. Schwartzman, and A. G. O'Toole. 2006. Conservation of the Pho regulon in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1910-1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monds, R. D., M. W. Silby, and H. K. Mahanty. 2001. Expression of the Pho regulon negatively regulates biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aureofaciens PA147-2. Mol. Microbiol. 42:415-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newell, P. D., R. D. Monds, and G. A. O'Toole. 2009. LapD is a bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP-binding protein that regulates surface attachment by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:3461-3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishimura, A., S. Moriya, H. Ukai, K. Nagai, M. Wachi, and Y. Yamada. 1997. Diadenosine 5′,5‴-P1,P4-tetraphosphate (Ap4A) controls the timing of cell division in Escherichia coli. Genes Cells 2:401-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plateau, P., and S. Blanquet. 1994. Dinucleoside oligophosphates in micro-organisms. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 36:81-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plateau, P., and S. Blanquet. 1982. Zinc-dependent synthesis of various dinucleoside 5′,5‴-P1,P3-tri- or 5″,5‴-P1,P4-tetraphosphates by Escherichia coli lysyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry 21:5273-5279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray, W. K., G. Zeng, M. B. Potters, A. M. Mansuri, and T. J. Larson. 2000. Characterization of a 12-kilodalton rhodanese encoded by glpE of Escherichia coli and its interaction with thioredoxin. J. Bacteriol. 182:2277-2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roa, B. B., D. M. Connolly, and M. E. Winkler. 1989. Overlap between pdxA and ksgA in the complex pdxA-ksgA-apaG-apaH operon of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 171:4767-4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romling, U., M. Gomelsky, and M. Y. Galperin. 2005. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol. Microbiol. 57:629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romling, U., and R. Simm. 2009. Prevailing concepts of c-di-GMP signaling. Contrib. Microbiol. 16:161-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schirmer, T., and U. Jenal. 2009. Structural and mechanistic determinants of c-di-GMP signalling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:724-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanks, R. M., N. C. Caiazza, S. M. Hinsa, C. M. Toutain, and G. A. O'Toole. 2006. Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based molecular tool kit for manipulation of genes from gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5027-5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Biotechnology (NY) 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wanner, B. L. 1996. Phosphorous assimilation and control of the phosphate regulon, p. 1357-1381. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 39.Zuber, S., F. Carruthers, C. Keel, A. Mattart, C. Blumer, G. Pessi, C. Gigot-Bonnefoy, U. Schnider-Keel, S. Heeb, C. Reimmann, and D. Haas. 2003. GacS sensor domains pertinent to the regulation of exoproduct formation and to the biocontrol potential of Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 16:634-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]