Abstract

The asymptomatic, chronic carrier state of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi occurs in the bile-rich gallbladder and is frequently associated with the presence of cholesterol gallstones. We have previously demonstrated that salmonellae form biofilms on human gallstones and cholesterol-coated surfaces in vitro and that bile-induced biofilm formation on cholesterol gallstones promotes gallbladder colonization and maintenance of the carrier state. Random transposon mutants of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium were screened for impaired adherence to and biofilm formation on cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes but not on glass and plastic surfaces. We identified 49 mutants with this phenotype. The results indicate that genes involved in flagellum biosynthesis and structure primarily mediated attachment to cholesterol. Subsequent analysis suggested that the presence of the flagellar filament enhanced binding and biofilm formation in the presence of bile, while flagellar motility and expression of type 1 fimbriae were unimportant. Purified Salmonella flagellar proteins used in a modified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) showed that FliC was the critical subunit mediating binding to cholesterol. These studies provide a better understanding of early events during biofilm development, specifically how salmonellae bind to cholesterol, and suggest a target for therapies that may alleviate biofilm formation on cholesterol gallstones and the chronic carrier state.

The serovars of Salmonella enterica are diverse, infect a broad array of hosts, and cause significant morbidity and mortality in impoverished and industrialized nations worldwide. S. enterica serovar Typhi is the etiologic agent of typhoid fever, a severe illness characterized by sustained bacteremia and a delayed onset of symptoms that afflicts approximately 20 million people each year (14, 19). Serovar Typhi can establish a chronic infection of the human gallbladder, suggesting that this bacterium utilizes novel mechanisms to mediate enhanced colonization and persistence in a bile-rich environment.

There is a strong correlation between gallbladder abnormalities, particularly gallstones, and development of the asymptomatic Salmonella carrier state (47). Antibiotic regimens are typically ineffective in carriers with gallstones (47), and these patients have an 8.47-fold-higher risk of developing hepatobiliary carcinomas (28, 46, 91). Elimination of chronic infections usually requires gallbladder removal (47), but surgical intervention is cost-prohibitive in developing countries where serovar Typhi is prevalent. Thus, understanding the progression of infection to the carrier state and developing alternative treatment options are of critical importance to human health.

The formation of biofilms on gallstones has been hypothesized to facilitate enhanced colonization of and persistence in the gallbladder. Over the past 2 decades, bacterial biofilms have been increasingly implicated as burdens for food and public safety worldwide, and they are broadly defined as heterogeneous communities of microorganisms that adhere to each other and to inert or live surfaces (17, 22, 67, 89, 102). A sessile environment provides selective advantages in natural, medical, and industrial ecosystems for diverse species of commensal and pathogenic bacteria, including Streptococcus mutans (40, 92, 104), Staphylococcus aureus (15, 35, 100), Escherichia coli (21, 74), Vibrio cholerae (39, 52, 107), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (23, 58, 73, 105). Bacterial biofilms are increasingly associated with many chronic infections in humans and exhibit heightened resistance to commonly administered antibiotics and to engulfment by professional phagocytes (54, 55, 59). The bacterial gene expression profiles for planktonic and biofilm phenotypes differ (42, 90), and the changes are likely regulated by external stimuli, including nutrient availability, the presence of antimicrobials, and the composition of the binding substrate.

Biofilm formation occurs in sequential, highly ordered stages and begins with attachment of free-swimming, planktonic bacteria to a surface. Subsequent biofilm maturation is characterized by the production of a self-initiated extracellular matrix (ECM) composed of nucleic acid, proteins, or exopolysaccharides (EPS) that encase the community of microorganisms. Planktonic cells are continuously shed from the sessile, matrix-bound population, which can result in reattachment and fortification of the biofilm or systemic infection and release of the organism into the environment. Shedding of serovar Typhi by asymptomatic carriers can contaminate food and water and account for much of the person-to-person transmission in underdeveloped countries.

Our laboratory has previously reported that bile is required for formation of mature biofilms with characteristic EPS production by S. enterica serovars Typhimurium, Enteritidis, and Typhi on human gallstones and cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes (18, 78). Cholesterol is the primary constituent of human cholesterol gallstones, and use of cholesterol-coated tubes creates an in vitro uniform surface that mimics human gallstones (18). It was also demonstrated that Salmonella biofilms that formed on different surfaces had unique phenotypes and required expression of specific EPS (18, 77), yet the factors mediating Salmonella binding to gallstones and cholesterol-coated surfaces during the initiation of biofilm formation remain unknown. Here, we show that the presence of serovar Typhimurium flagella promotes binding specifically to cholesterol in the early stages of biofilm development and that the FliC subunit is a critical component. Bound salmonellae expressing intact flagella provided a scaffold for other cells to bind to during later stages of biofilm growth. Elucidation of key mechanisms that mediate adherence to cholesterol during Salmonella bile-induced biofilm formation on gallstone surfaces promises to reveal novel drug targets for alleviating biofilm formation in chronic cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and molecular biology techniques.

The Salmonella strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and agar were used for bacterial growth, creation of mutants, biofilm assays, and flagellum purification. For biofilm formation experiments, strains were grown on a rotating drum in the presence or absence of 3% crude ox bile extract (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to mid- to late exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.6 to 0.8). When necessary, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml; and tetracycline (Tet), 15 μg/ml. Molecular cloning and PCR were performed using established protocols. Plasmids were purified using QIAprep spin miniprep kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and were transformed by electroporation as previously described (85).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and relevant characteristics

| S. Typhimurium strain | Characteristics | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| JSG210 | ATCC 14028s (CDC6516-60); wild type | ATCC |

| JSG526 | flhC98::Tn10 (TH2934) | Gift from K. Hughes |

| JSG1174 | Δ(fim-aph-11::Tn10)-391 lpfC::Kan agfB::Cam pefC::Tet | Gift from A. Baumler |

| JSG1178 | hin108::Tn10d-Cam (FljB locked off; FljB− FliC+) | Gift from B. Cookson |

| JSG1179 | hin108::Tn10d-Cam fliC::Tn10 (FljB locked on; FljB+ FliC−) | Gift from B. Cookson |

| JSG1190 | hin108::Tn10d-Cam fliC::Tn10 (FljB locked off; FljB− FliC−) | Gift from B. Cookson |

| JSG1547 | motA595::Tn10 | Gift from T. Lino |

| JSG3089 | fimW::Kan | Gift from S. Clegg |

| JSG3055 | fimW::Tn10d-Tet; site 1, 17 insertions | This study |

| JSG3058 | fimW::Tn10d-Tet; site 2, 1 insertion | This study |

| JSG3059 | flhA::Tn10d-Tet; 9 insertions | This study |

| JSG3060 | fliF::Tn10d-Tet; 3 insertions | This study |

| JSG3061 | fliA::Tn10d-Tet; 2 insertions | This study |

| JSG3062 | fliJ::Tn10d-Tet; 1 insertion | This study |

| JSG3063 | fliL::Tn10d-Tet; 1 insertion | This study |

| JSG3099 | fimW::Tn10-Tet fim::Kan | This study, gift from A. Baumler |

| JSG3214 | ATCC 14028s/pISF101 | This study, gift from A. Baumler |

| JSG3064 | ompC::Tn10d-Tet; 5 insertions | This study |

| JSG3065 | sseI::Tn10d-Tet; 1 insertion | This study |

| JSG3073 | ompC::Tn10d-Tet; 9 insertions | This study |

Transposon mutagenesis and screening.

Cholesterol-binding-deficient, tetracycline-resistant serovar Typhimurium strains were created by random transposon mutagenesis using an established method (85). Briefly, Tn10d-Tet transposons were introduced into wild-type serovar Typhimurium. Strains containing Tn10d transposon insertions were selected on plates containing LB agar with Tet, and 40,000 individual colonies were pooled in LB broth containing Tet. The serovar Typhimurium transposon mutant pool was grown to log phase (OD600, 0.6) in LB broth containing Tet with 3% crude ox bile extract, and 100-μl portions were added to siliconized Eppendorf tubes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) coated with 1 mg of chromatography-grade cholesterol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Following incubation for 24 h at room temperature on a Nutator shaker (Labnet International, Edison, NJ), 10 μl of the planktonic, nonadherent culture was removed and added to 90 μl of fresh LB broth containing Tet with 3% crude ox bile in a new cholesterol-coated, siliconized Eppendorf tube. This panning for cholesterol-binding-deficient bacteria was repeated every 24 h for 10 days. Serial dilutions of the final planktonic culture were plated on LB agar containing Tet, and 500 individual colonies were screened for loss of or a defect in biofilm formation on cholesterol-coated surfaces (values that were 0 to 25% of wild-type values) and preservation of biofilm formation on glass and plastic coverslips (values that were 75 to 100% of wild-type values). Colonies were confirmed to have a non-biofilm-forming (on cholesterol) phenotype by back-transduction using P22 HT int-105.

Cholesterol, glass, and plastic surface biofilm assays.

Salmonella strains were tested to determine their abilities to form biofilms in the tube biofilm assay (TBA) and on cholesterol-coated glass and plastic coverslips as described previously (18). In brief, log-phase Salmonella strains grown with or without 3% crude ox bile were added to cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes or 24-well plastic plates (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) containing Chromerge-cleaned glass, plastic, and cholesterol-coated coverslips. The resulting cultures were incubated on a Nutator shaker at room temperature for 6 days. Every 24 h, the medium was removed, the tubes were washed three times with LB medium, and fresh medium (LB medium with or without 3% bile) was added. Bound bacterial samples were fixed at 60°C for 1 h, and a solution of 0.1% crystal violet (gentian violet in isopropanol-methanol-1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] [1:1:18]) was then added to stain cells for 5 min at room temperature. The tubes were washed with 1× PBS, and the dye was extracted using 33% acetic acid and quantified by determining the optical density at 570 nm.

DNA sequencing and bioinformatics.

Sequencing of transposon mutant genomic DNA from serovar Typhimurium cholesterol-binding-deficient colonies with primer JG1787 (5′-CCTTTTTCCGTGATGGTA-3′) was performed using an Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA capillary analyzer and BigDye cycle fluorescent terminator chemistry at the Plant-Microbe Genomics Facility at The Ohio State University. Transposon insertion sites of recovered sequences were determined using BlastX at the NCBI (43).

Assay of adherence of live and dead bacteria.

Wild-type and flagellar transcriptional activator (FlhC) mutant strains of serovar Typhimurium were grown overnight at 37°C in LB broth with or without 3% crude ox bile extract, diluted 1:100, and grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. Bacteria in these cultures were killed by incubation for 40 min in 10% formalin or by heat fixation for 20 min at 65°C. Triplicate 100-μl aliquots of live and dead salmonellae were added to 24-well polystyrene tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) coated with 1 mg of cholesterol per well, and the plates were centrifuged at 165 relative centrifugal force (RCF) for 5 min to initiate contact between the bacteria and cholesterol. Three hours of incubation at room temperature for adherence was followed by five washes in 1× PBS, staining of wells with a 0.1% crystal violet solution (gentian violet in isopropanol-methanol-1× PBS [1:1:18]) for 5 min, and five more washes with 1× PBS. The dye retained by bound cells was extracted using 33% acetic acid and was quantified by determining the optical density at 570 nm.

Live and dead scaffold assay.

Late-log-phase cultures of serovar Typhimurium wild-type and flagellar transcriptional activator (FlhC) mutant strains were formalin fixed or heat killed as described above, and 100-μl were aliquots added to siliconized Eppendorf tubes coated with 1 mg of chromatography-grade cholesterol. Following incubation at room temperature on a Nutator shaker for 24 h, cultures were removed, and the tubes were washed three times in LB broth to remove nonadherent bacteria. Live cultures of late-log-phase wild-type or ΔflhC serovar Typhimurium strains were added to the tubes, and biofilm formation was examined using the TBA as described above.

Purification of serovar Typhimurium flagellin.

Serovar Typhimurium wild-type, phase-1-locked (FliC; H:i) mutant, phase-2-locked (FljB; H:1,2) mutant, and flagellin (FliC) mutant strains were grown to late log phase in LB medium at 37°C. The resulting cultures (500 ml) were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 15 min. The cell pellets were washed once, resuspended in 15 ml 1× PBS, and sheared mechanically for 3 min at 30,000 rpm using a Power Gen 125 tissue homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Flagellar filaments were separated from cellular debris by centrifugation for 10 min at 8,000 × g. The flagellum-containing supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. Filaments were gently resuspended overnight in 1× PBS with slow shaking at 4°C and then centrifuged at 100,000 × g. This 24-h washing cycle was repeated twice, and the final pellets of purified serovar Typhimurium flagellin were resuspended in 1× PBS and stored at −20°C. The protein concentrations of isolated flagellin were determined with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL), and the purity was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and staining with GelCode Blue reagent (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL).

Western blotting.

Monoclonal antibodies against Salmonella species flagella (Maine Biotechnology Services, Portland, ME) and FliC subunit protein (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) were used to probe purified flagellin from serovar Typhimurium wild-type, FljB mutant, and FliC mutant strains in a Western blot analysis. For each sample, 10 μl containing 1 μg purified flagellin was mixed with an equal volume of SDS-PAGE loading buffer and boiled for 15 min. Preparations were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA) using a Trans-Blot semidry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were blocked overnight in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and incubated with antiflagellum antibody (diluted 1:200 in PBS; Maine Biotechnology Services, Portland, ME) or anti-FliC antibody (5 μg diluted in 5 ml PBS; BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for 4 h. Goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) diluted 1:5,000 in PBS (with 2 h of incubation) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) were used to detect bound antibodies. Bands were visualized after exposure and development on HyBlot CL autoradiography film (Denville Scientific Inc., Metuchen, NJ). All washes were performed with 1× PBS.

Subunit binding ELISA.

Purified flagellin from serovar Typhimurium wild-type, FljB mutant, and FliC mutant strains was assayed to determine its ability to bind cholesterol using a modified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Chromatography-grade cholesterol was dissolved in anhydrous ether (J. T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ) at a concentration of 25 mg/ml, and 100-μl aliquots were added to polystyrene wells in 96-well Microtest tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Six 1-μg replicates of each purified flagellin sample were then added to the cholesterol-coated wells. Following 3 h of binding and incubation at room temperature, the plates were washed three times in 1× PBS and blocked overnight with 3% BSA. Wells were emptied, washed, and incubated with antiflagellum antibody (diluted 1:20 in 0.3% BSA) or anti-FliC antibody (diluted 1:100 in 0.3% BSA) for 2 h, each in triplicate. Another washing step was followed by addition of goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) diluted 1:5,000 in 0.3% BSA and incubation for 1 h. Measurements of flagellin binding to cholesterol were obtained using a Bio-Rad HRP substrate kit according to the manufacturer's specifications. Reaction products were transferred to an uncoated 96-well plate to determine the optical density at 415 nm.

RESULTS

Identification of serovar Typhimurium mutants deficient for binding to cholesterol but not for binding to glass or plastic.

The molecular genetic mechanisms that mediate initiation of biofilm formation vary with the growth medium and substrate and are beginning to be elucidated for microorganisms such as E. coli (21, 74, 75), S. aureus (15, 35, 100), Enterococcus faecalis (38, 97), and Pseudomonas spp. (58, 72, 73, 84). As described previously, S. enterica serovars Typhimurium, Enteritidis, and Typhi form mature biofilms on cholesterol gallstone surfaces and cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes (tube biofilm assay [TBA]) but not on uncoated tubes when they are grown in the presence of 3% crude ox bile extract (18). To identify novel genes that regulate binding to cholesterol, Tn10d-Tet transposon mutagenesis was performed with serovar Typhimurium wild-type strain ATCC 14028s. A total of 40,000 colonies were pooled to generate a mutant library of random Tn10d transposon insertions. The mutant pool was grown to log phase in LB broth containing Tet with 3% crude ox bile extract, and 100-μl portions were added to siliconized Eppendorf tubes coated with 1 mg of cholesterol. Following incubation for 24 h, 10 μl of the planktonic, nonadherent culture was removed and added to 90 μl of fresh LB broth containing Tet with 3% bile in new cholesterol-coated tubes. The panning for cholesterol-binding-deficient bacteria was repeated every 24 h for 10 days, and the final planktonic cells were diluted and plated.

To determine if the ability of these mutants to form biofilms in the TBA, as well as on other surfaces, was affected, 500 individual colonies were assayed in the presence of bile to determine their binding to cholesterol-coated tubes or to glass or plastic coverslips. We identified 49 strains deficient in biofilm formation on cholesterol-coated tubes but not on glass or plastic surfaces, demonstrating that a specific loss of cholesterol binding was mediated by the mutations. To rule out the possibility of second-site mutations, mutants were transduced back into the parent strain, and their biofilm-forming phenotypes were confirmed.

Sequencing of Tn10d transposon insertion sites.

Direct genomic DNA sequencing from the transposon 5′ end and sequence analyses revealed that the Tn10d insertions mapped to several genes corresponding to the serovar Typhimurium loci fimW, ompC, flhA, fliF, fliA, fliJ, fliL, and sseI (Table 2). Eighteen Tn10d insertion sites were in the fimW open reading frame; one was at bp 98 (JSG3058) in the open reading frame (ORF), and 17 others were at bp 125 (JSG3055). The colonies with transposon insertions in fimW that were recovered in the cholesterol-binding screen were more numerous than the colonies with transposon insertions in any other gene that were recovered. FimW negatively regulates production of type 1 fimbriae by interacting with FimY (83) and possibly with FimZ (96); the latter two proteins independently activate the PfimA promoter, which controls the expression of the fim structural genes (83). Serovar Typhimurium chromosomal fimW mutants expressed 4- to 8-fold more type 1 fimbriae than the parent strain (96). Therefore, serovar Typhimurium strains carrying Tn10d insertions in fimW exhibit hyperfimbriate phenotypes, suggesting that overproduction of type 1 fimbriae inhibited adherence to cholesterol.

TABLE 2.

Transposon insertion sites, frequencies, and functions

| Gene | No. of coloniesa | No. of unique insertions | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| fimW | 18 | 2 | Inhibitor of type 1 fimbria regulator FimZ |

| ompC | 14 | 2 | Outer membrane protein; passive diffusion of ions, hydrophilic solutes |

| flhA | 9 | 1 | Flagellar export apparatus, biosynthesis membrane protein |

| fliF | 3 | 1 | Flagellar cytoplasmic anchor MS ring protein |

| fliA | 2 | 1 | Flagellar biosynthesis sigma factor |

| fliJ | 1 | 1 | Rod/hook and filament biosynthesis chaperone |

| fliL | 1 | 1 | Basal body protein; stability of MotAB complexes of MS ring |

| sseI | 1 | 1 | Secreted effector; colocalizes with host polymerizing actin cytoskeleton |

A total of 49 mutants were identified from the 500 mutant colonies screened for the lack of an ability to form cholesterol (but with the ability to form a biofilm on glass or plastic surfaces).

Nine identical Tn10d transposon insertions in flhA were located at bp 1917 (JSG3059). The cytoplasmic membrane protein FlhA mediates type III export of axial components of the Salmonella flagellum and the scaffolding proteins for flagellum assembly (45, 82). All three Tn10d insertions in the fliF open reading frame were located downstream of the start site at bp 872 (JSG3060). Structural subunits of the transmembrane protein FliF comprise the membrane-supramembrane ring (MS ring) and proximal rod of the flagellar basal body in serovar Typhimurium and have been shown to interact with the chemotactic motor-switch protein FliG (94, 95, 99). Two Tn10d insertion sites in fliA (JSG3061) were located at bp 532 relative to the start codon. The conserved alternative sigma factor σ28 encoded by the class 2 regulatory gene fliA directs transcription from class 3 promoters of flagellar filament late assembly genes in E. coli (16, 57) and serovar Typhimurium (16, 32, 71). The Tn10d insertion in JSG3062 was located in the fliJ open reading frame at bp 142 relative to the start codon. FliJ is a soluble, cytoplasmic chaperone of the type III flagellar protein apparatus that associates with the transmembrane domain of FlhA and is implicated in export of filament (FliC) and rod and hook (FlgD) substrates (31, 61, 66). One Tn10d transposon insertion site was located downstream of the fliL start site at bp 252 (JSG3063). The function of the membrane-associated component of the flagellar basal body encoded by fliL is unknown (86). Recent evidence suggests that FliL prevents rod fracture caused by torsional stress during swarming motility (4).

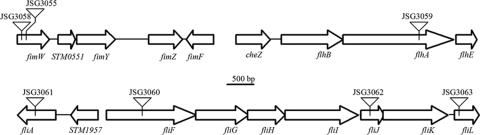

In sum, the majority (34/49 or 70%) of the Tn10d insertions disrupted genes involved in flagellar and type 1 fimbrial biosynthesis and structural components, suggesting that the presence of the serovar Typhimurium flagella mediates binding to cholesterol to initiate biofilm formation on cholesterol-coated surfaces, whereas overproduction of fimbriae is not important for establishment of a biofilm on cholesterol. Figure 1 A shows a schematic diagram of the transposon insertion sites in fimbria- and flagellum-related genes found by random mutagenesis.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of Tn10d transposon insertion sites in serovar Typhimurium cholesterol biofilm mutants with mutations affecting type 1 fimbria and flagellum structure and biogenesis. The arrows indicate the sizes and orientations of neighboring genes, and the triangles indicate the locations of transposon insertions.

Overexpression of type 1 fimbriae in serovar Typhimurium has a negative effect on biofilm formation on cholesterol.

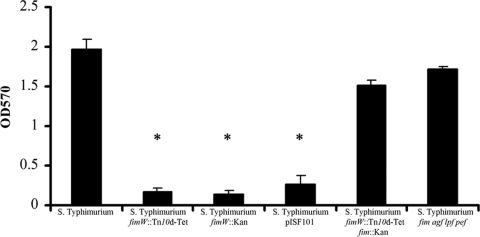

Fimbriae have been shown to mediate adherence during initiation of biofilm formation and cell-cell interactions during biofilm growth for a variety of microorganisms (22, 73). The serovar Typhimurium genome contains 13 putative fimbrial operons, some of which are not expressed in vitro (70). Type 1 fimbriae have been shown to be important for biofilm formation on HEp-2 tissue culture cells, the murine intestinal epithelium, and the chicken intestinal epithelium (9, 51) but not on human gallstones incubated with bile (78). A serovar Typhimurium SR11 strain having mutations in four fimbrial operons (fim, agf, lpf, and pef) was added to the TBA to examine biofilm formation on cholesterol-coated surfaces. In the presence of bile, the amount of biofilm formed by the quadruple-mutant SR11 strain equaled the amount of biofilm formed by serovar Typhimurium wild-type strain ATCC 14028s (Fig. 2), suggesting that fimbriae encoded by the fim, agf, lpf, and pef operons do not contribute to biofilm formation in this static assay.

FIG. 2.

Overexpression of type 1 fimbriae inhibits biofilm formation on cholesterol-coated surfaces, while normal or decreased expression of type 1 fimbriae has no effect. Biofilm formation by serovar Typhimurium strains grown with 3% crude ox bile extract on cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes was examined. Crystal violet-stained TBA biofilms were extracted with acetic acid, and absorbance at 570 nm was measured. *, statistically significantly different (P < 0.005) based on a two-tailed Student t test. OD570, optical density at 570 nm.

To test whether serovar Typhimurium cholesterol-binding-deficient mutants with mutations affecting type 1 fimbriae could form mature biofilms, strains having Tn10d transposon insertions in fimW were added to cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes in the TBA as described previously (18). As shown in Fig. 2, a fimW::Tn10d-Tet mutation rendered serovar Typhimurium deficient for biofilm formation in the presence of 3% bile. When fimW was disrupted by insertion of a kanamycin cassette, the resulting serovar Typhimurium mutant expressed 4- to 8-fold more type 1 fimbriae than the parent strain (96). This fimW::Kan mutant was deficient for biofilm formation at levels similar to those of the strain having a transposon insertion in fimW (Fig. 2). To further test whether overexpression of type 1 fimbriae could affect biofilm formation in an otherwise wild-type background, a strain with pISF101, which contains the type 1 fimbrial gene cluster and results in a hyperfimbriate phenotype, did not form a biofilm in the TBA (Fig. 2).

As mentioned above, FimW negatively regulates FimY, a multifunctional protein that positively regulates production of fimbriae by activating the fimA promoter (83). To determine whether the fimW-mediated effects on biofilm formation were a direct result of disruption of type 1 fimbriae, a strain having a deletion of the type 1 fimbrial operon marked with a kanamycin cassette was transduced in the fimW::Tn10d-Tet background. The resulting strain lacking fimW and type 1 fimbrial genes (including fimA) exhibited wild-type levels of biofilm formation in the TBA (Fig. 2). Collectively, these results demonstrate that overexpression of type 1 fimbriae has a negative effect during Salmonella binding to cholesterol and that the interference prevents subsequent maturation of a cholesterol biofilm formed by the bacterium.

Flagellum-mediated binding to cholesterol is necessary for biofilm development in serovar Typhimurium.

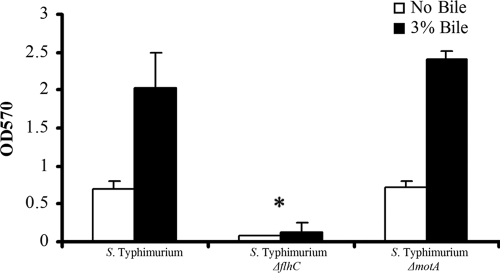

The highly ordered transcriptional hierarchy controlling expression of flagella is comprised of three classes of genes and is regulated by many global signals (32, 44). Therefore, it is no surprise that flagella make various contributions to biofilm formation in members of the Enterobacteraceae, such as V. cholerae (50, 68, 102, 103), E. coli (48, 60, 74, 75), and P. aeruginosa (26), depending on the environmental conditions, such as binding substrate material, nutrient limitation, temperature, medium flow rate, and other factors (6, 63, 73). Expression of the serovar Typhimurium flagella has been shown to inhibit biofilm formation on polystyrene wells (93) but to promote biofilm development on human gallstones when bile is added to the growth medium (77, 78). However, the stage at which this appendage positively or negatively impacts Salmonella biofilms has not been defined. To examine whether production of the flagellar filament is necessary for biofilm formation on cholesterol, a mutation in the gene at the apex of transcriptional regulation (flhC) in serovar Typhimurium was created. The resulting mutant strain did not form a mature biofilm on cholesterol, providing direct evidence of the importance of flagella during biofilm development (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Flagella are necessary for biofilm formation on cholesterol-coated surfaces, whereas motility is dispensable. Serovar Typhimurium strains were grown with and without 3% crude ox bile extract and added to cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes. Biofilms were stained with crystal violet and extracted with acetic acid, and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured. *, statistically significantly different (P < 0.005) based on a two-tailed Student t test. OD570, optical density at 570 nm.

The presence of, but not the motility mediated by, the serovar Typhimurium flagella is important for biofilm formation on cholesterol surfaces.

As demonstrated above, mutations in serovar Typhimurium flagellum structural and biosynthesis genes affected binding to and biofilm formation on cholesterol. To determine if the physical presence of the flagellar filament or flagellum-mediated motility was required for biofilm formation, mutants that expressed flagella but could not swim were tested. In the TBA, a serovar Typhimurium motA mutation (which eliminates flagellar motility but not synthesis) (24) did not reduce the levels of biofilm on cholesterol surfaces in the presence or absence of bile compared to the results obtained for the parent strain, suggesting that motility is not critical for development of serovar Typhimurium biofilms on cholesterol-coated surfaces (Fig. 3).

The number of surface-expressed serovar Typhimurium flagella is not regulated by bile.

The presence of bile was shown to modestly downregulate serovar Typhimurium motility and flagellar gene expression in β-galactosidase assays using MudJ fusions to flhC, flgC, and fliC (76). Interestingly, bile is required for formation of mature biofilms on cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes, and flagellum biosynthesis mediates, at least in part, attachment to this surface for biofilm development. To determine if the bile-mediated downregulation of flagellar genes resulted in a loss of flagella or whether bile altered the expression of flagella at a posttranscriptional level, wild-type and flhC mutant strains of serovar Typhimurium were grown to late exponential phase with or without 3% bile and examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). For the wild-type strain the average number of flagella was nearly 6 flagella per bacterium regardless of the growth conditions, whereas no flagella were observed for the flhC mutant (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Therefore, while exposure to bile may transcriptionally downregulate flagellar genes, bile has no effect on the number of flagella.

Formalin-fixed and heat-killed salmonellae expressing intact flagella bind to cholesterol.

If flagella mediate attachment to cholesterol, then dead salmonellae expressing intact flagella should bind to cholesterol in the TBA. Wild-type and ΔflhC strains of serovar Typhimurium were fixed in 10% formalin for 40 min or heat killed at 65°C for 20 min and added to cholesterol-coated wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate. Live and dead wild-type cells bound to cholesterol following 3 h of incubation, and the association was only modestly enhanced by bile (Table 3). Strains lacking FlhC production did not bind to cholesterol under any of the conditions tested, further suggesting that the serovar Typhimurium flagellar filament mediates binding to cholesterol in the early stages of biofilm formation.

TABLE 3.

Binding quantification assaya

| Strain | Growth conditions | Live | Dead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serovar Typhimurium | LB medium | + | + |

| wild type | LB medium + 3% bile | + | + |

| Serovar Typhimurium | LB medium | − | − |

| flhC mutant | LB medium + 3% bile | − | − |

A 3-h binding quantification assay was performed with cholesterol-coated wells containing live or dead serovar Typhimurium wild-type and flhC mutant strains. Crystal violet-stained material was extracted with acetic acid, and the optical density at 570 nm was determined for quantification. +, binding equivalent to wild-type binding under appropriate conditions; −, severe defect in or complete loss of adherence (values that were 0 to 10% of the wild-type values).

Dead salmonellae bound to cholesterol provide a scaffold for biofilm formation by live cells.

To determine if flagellum-mediated binding could provide a scaffold for serovar Typhimurium biofilm formation, formalin-fixed salmonellae were incubated in cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes for 24 h and washed vigorously with 1× PBS. A late-logarithmic culture of wild-type serovar Typhimurium grown in 3% bile was added on top of the bound cells, and the standard 6-day TBA was performed. When formalin-fixed salmonellae were added, these killed, bound cells were able to support biofilm formation by live wild-type serovar Typhimurium, and the amounts of the biofilms were larger than the amounts of the biofilms for salmonellae grown in the TBA without this scaffold (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Biofilm formation on cholesterol or on formalin-fixed bacteria bound to cholesterol

| Organism grown with 3% bile | Biofilm development ona: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | Dead cells | |

| Serovar Typhimurium wild type | + | ++ |

| Serovar Typhimurium flhC mutant | − | +++ |

Biofilms were grown on cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes or on a substrate consisting of inactivated, bound cells in the TBA. The dye was extracted with acetic acid, and the optical density at 570 nm was determined for quantification. +, formation of a robust, mature biofilm (wild-type amount); ++, amount of biofilm that was 1.5- to 1.99-fold larger than the wild-type amount; +++, amount of biofilm that was ≥2.0-fold larger than the wild-type amount; −, severe defect in or complete loss of biofilm formation (amount that was 0 to 10% of the wild-type amount).

To test whether the presence of flagella contributed to later events during biofilm development, a live serovar Typhimurium flhC mutant culture was added to a scaffold of bound, dead wild-type cells, and a TBA was performed. The flhC mutant, while deficient in biofilm formation on cholesterol-coated surfaces (Fig. 3), was able to form a biofilm on the dead cell scaffold, suggesting that serovar Typhimurium flagellar filaments, while necessary for binding to cholesterol, do not contribute to subsequent biofilm development (Table 4). Furthermore, the amount of biofilm formed by an flhC mutant on dead cells was significantly larger the amount of biofilm formed by the wild-type strain under the same conditions, suggesting that after mediating the initial binding, flagella may inhibit biofilm growth (Table 4).

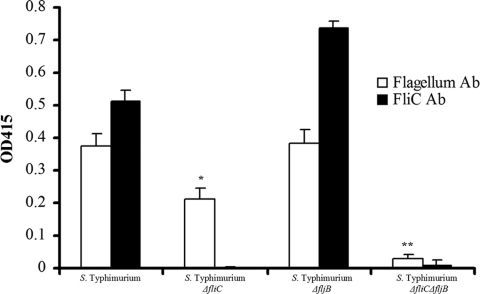

Serovar Typhimurium flagellar subunit FliC is critical for binding to cholesterol.

The flagellar filament of S. enterica is approximately 10 μm long and is comprised of two antigenically distinct flagellin proteins, FliC (H:i) and FljB (H:1,2) (16, 25). During the well-characterized phase variation process, these subunits are alternatively expressed by a posttranscriptional control mechanism (1, 10, 87). To determine which subunit protein mediated binding of the serovar Typhimurium flagellar filament to cholesterol, antibody to Salmonella whole flagella and FliC was used in a quantitative binding ELISA. Briefly, flagella were isolated and purified from serovar Typhimurium wild-type, ΔfliC, ΔfljB, and ΔfliC ΔfljB strains using a mechanical shearing protocol adapted from the protocol of Andersen-Nissen et al. (3). Wild-type and phase-locked mutant flagellin preparations (1 μg each) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Based on the amino acid sequences, the predicted molecular masses of the FliC and FljB proteins were 51.6 and 52.5 kDa, respectively (98), and the approximately 1-kDa difference was detected by Coomassie blue staining (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material) and Western blotting. Monoclonal antiflagellin antibodies (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material) that recognized a peptide that is present in both FliC and FljB or only in FliC were used. The identity of each band was confirmed by comparing the wild-type and mutant lanes (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Purified proteins from all samples were added to cholesterol-coated wells of a 96-well tissue culture plate and analyzed by a modified ELISA. Equal amounts of the flagella from the wild-type and ΔfljB strains bound to cholesterol, and the amounts were significantly larger than the amounts observed for an fliC mutant, suggesting that FliC is the critical serovar Typhimurium flagellar subunit that mediates binding to cholesterol (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Expression of purified flagellum proteins from serovar Typhimurium wild-type, fliC mutant, fljB mutant, and fliC fljB mutant strains adhering to cholesterol-coated wells. An ELISA was performed using antiflagellum or anti-FliC monoclonal antibodies, and binding to cholesterol was quantified by measuring the bound secondary HRP-conjugated substrate using the optical density at 415 nm (OD415). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences based on a two-tailed Student t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005). Ab, antibody.

DISCUSSION

Approximately 5% of patients suffering from typhoid fever carry Salmonella in the gallbladder (53), and evidence indicates that there is a high correlation between individuals who become carriers and individuals who have gallstones (28, 47). Because antibiotic treatments are ineffective at removing chronic infections in such cases (47), we hypothesized and have demonstrated that the asymptomatic presence of serovar Typhi is frequently a result of formation of biofilms on cholesterol gallstone surfaces. In this work we show that the flagellar filament, specifically the FliC subunit, of serovar Typhimurium is necessary for and specific for cholesterol binding during the initiation of biofilm formation.

Bacteria express a diverse arsenal of factors during biofilm development that are uniquely required depending on environmental stimuli, such as the growth medium and the substrate hydrophobicity and charge. It was previously shown that S. enterica serovars Typhi, Typhimurium, and Enteritidis formed bile-induced biofilms on human cholesterol gallstones and cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes in vitro (18, 78). To determine the critical genes for early biofilm events, specifically the genes involved in attachment, a randomly mutagenized serovar Typhimurium strain was screened using the TBA for loss of adherence. Genomic DNA from mutants that did not bind to cholesterol but formed biofilms on glass and plastic surfaces were sequenced to locate the Tn10d insertion site. Disruptions in genes affecting type 1 fimbria and flagellum structure and biogenesis were the disruptions observed most frequently, and fimW disruptions were prevalent.

Tn10d insertions were also found in genes encoding an outer membrane protein (ompC) and a translocated effector of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) type III secretion system (sseI). OmpC is necessary for binding and biofilm formation in the presence of bile, possibly because it mediates electrostatic interactions between salmonellae and the cholesterol surface, promotes overall biofilm health as a nutrient channel, or regulates cell-cell interactions, as it does in E. coli biofilms (79). SseI is a secreted effector protein belonging to the GDSL family of lipases that colocalizes with the polymerizing actin cytoskeleton (65). SPI-1 has been implicated in directing cholesterol distribution during entry into mammalian cells (33), and GDSL proteins associated with SPI-2 have been shown to hydrolyze phospholipids and esterify cholesterol intracellularly (11, 69). The lambdoid phage Gifsy-2 encodes SseI (29, 65), and the receptor for Gifsy-2 is OmpC (36). Although the Gifsy bacteriophages and SPI-2 secreted effectors are generally virulence factors of serovar Typhimurium in mice, the association between SseI and OmpC and the known interaction of SseI with cholesterol suggest a possible role for adherence to or modification of cholesterol during biofilm formation.

The presence of fimbriae is attributed in part to serovar Typhimurium biofilm formation on HEp-2 tissue culture cells and the intestinal epithelia of mice and chickens (7, 9, 51). In studies by Prouty et al., a serovar Typhimurium SR11 strain having mutations in four fimbrial operons was observed to adhere to and form biofilms on cholesterol gallstones in a manner similar to the manner observed for wild-type serovar Typhimurium (78). Similarly, the amount of biofilm formed by a quadruple-mutant SR11 strain was the same as the amount formed by wild-type serovar Typhimurium both in the presence and in absence of bile in the TBA, suggesting that fimbriae encoded by the fim, agf, lpf, and pef operons do not affect biofilms on cholesterol-coated surfaces.

FimW has recently been shown to downregulate production of type 1 fimbriae by inhibiting FimY, a protein that enhances expression of the fim structural genes by activating the fimA promoter (83), and chromosomal fimW mutants expressed 4- to 8-fold more type 1 fimbriae than the parent strain (96). The fimW::Kan and fimW::Tn10d-Tet serovar Typhimurium strains and a separate type 1 fimbria-overexpressing serovar Typhimurium strain did not form a biofilm on cholesterol-coated Eppendorf tubes, and introduction of a mutation in the type 1 fimbrial gene cluster into a fimW mutant background restored the amount of biofilm formation to that by wild-type serovar Typhimurium. These data suggest that overexpression of type 1 fimbriae has a negative effect during Salmonella binding to cholesterol and subsequent biofilm formation by the bacterium.

Flagella promote surface binding during biofilm formation (73, 74), as well as adhesion during colonization of tissue culture cells and mucus by P. aeruginosa (56, 81), Campylobacter jejuni (62), E. coli (34), Yersinia enterocolitica (45a), and S. enterica (2, 12, 27, 49). To examine whether the physical presence of the flagellar filament was necessary for biofilm formation on cholesterol, a serovar Typhimurium flhC mutant was examined using the TBA and shown not to form a mature biofilm on cholesterol. These results provide direct evidence that flagella are important during biofilm development.

Flagellum-mediated motility and chemotaxis differentially contribute to colonization and biofilm formation depending on environmental cues (37, 64, 73, 74, 77). Bile, for example, increases motility and is a chemical attractant at physiological concentrations for V. cholerae (13), acts as a repellent for Helicobacter pylori (106), and enhances tumbling frequency while modestly downregulating motility in S. enterica (76). Serovar Typhimurium mutant strains lacking a motor function (motA) were analyzed to determine whether they formed a biofilm using the TBA. Loss of flagellar motility had no significant effect on biofilm development in LB broth with or without bile. These results indicate that flagellar motility is dispensable for biofilm formation on cholesterol surfaces.

Bile has also been shown to affect transcription of the serovar Typhimurium flagellum structural genes flhC, flgC, and fliC (76). We report here that wild-type salmonellae grown with and without bile and visualized by TEM express the same amount of flagella, suggesting that prolonged exposure to bile does not alter the ultimate production of flagella. Thus, the reduced levels of flhC, flgC, and fliC transcription in the presence of bile, while slightly less than the levels in the absence of bile, are still above the threshold level necessary for normal flagellum production under these conditions and allow flagellum-mediated binding to cholesterol.

To determine whether dead cultures of serovar Typhimurium could bind to cholesterol in the absence of secreted factors, formalin-fixed or heat-killed wild-type and flhC mutant strains were added to cholesterol-coated wells. The results of these experiments indicate that surface expression of intact flagella is sufficient and necessary to mediate binding to cholesterol. Interestingly, bound and inactivated cells provided a scaffold for biofilm formation by live, wild-type cells in the TBA, and the amounts of the biofilms were larger than the amounts of the biofilms produced by salmonellae grown without this scaffold in the TBA. The serovar Typhimurium flagellum (FlhC) mutant was added to a layer of adherent, dead cells, and biofilm development was examined. There was an increase in biofilm formation by the flhC mutant on a substrate consisting of bound bacteria, suggesting that the flagellar filament, while critical for initial binding to and biofilm formation on cholesterol, does not mediate subsequent biofilm growth following attachment.

The flagellar filament of S. enterica is comprised of two antigenically distinct subunit proteins, FliC (H:i) and FljB (H:1,2), and this is a pathogen-associated molecular pattern detected by mammalian cells via surface-expressed Toll-like receptor 5 and cytosolic Nod-like receptors (30, 80). Secretion of interleukin-1β by mouse cell lines is activated comparably by the FliC and FljB flagellins (88), but memory CD4+ T cells preferentially recognize FliC during adaptive immunity and Salmonella committed to expressing only FljB is attenuated in vivo (8, 41). To determine which flagellar subunit mediated adherence to cholesterol, ELISA was performed using antiflagellum or anti-FliC antibodies against purified flagellum proteins from serovar Typhimurium wild-type, fliC mutant, fljB mutant, and fliC fljB mutant strains bound to cholesterol-coated wells. The FliC subunit was shown to be a critical factor for mediating attachment to cholesterol. Interestingly, S. Typhi is monophasic, harboring only the fliC gene (5), and FliC expression was anatomically restricted to certain tissues during systemic serovar Typhimurium infections in mice (20).

In this work, we identified a number of Salmonella factors that mediate binding to and subsequent biofilm development on cholesterol-coated surfaces. Specifically, we showed that overexpression of fimbriae is detrimental, while expression of the serovar Typhimurium flagellar filament mediates adherence to cholesterol but not to glass or plastic surfaces primarily with the FliC subunit, which initiates biofilm formation, but inhibits subsequent biofilm development. It could be hypothesized that flagellar production is downregulated as a biofilm develops. This new understanding of the events during Salmonella biofilm formation on cholesterol-coated surfaces provides therapeutic targets with the potential for alleviating asymptomatic gallbladder carriage of S. Typhi and thus the human-to-human transmission that makes this pathogen a global concern.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant AI066208 to J.S.G. and by a graduate education fellowship from Ohio State University Public Health Preparedness for Infectious Diseases to R.W.C.

We thank Richard Montione of the Ohio State University Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility for technical support with TEM and several laboratories that contributed strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 January 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldridge, P. D., C. Wu, J. Gnerer, J. E. Karlinsey, K. T. Hughes, and M. S. Sachs. 2006. Regulatory protein that inhibits both synthesis and use of the target protein controls flagellar phase variation in Salmonella enterica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:11340-11345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen-Vercoe, E., and M. J. Woodward. 1999. The role of flagella, but not fimbriae, in the adherence of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis to chick gut explant. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:771-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen-Nissen, E., K. D. Smith, R. Bonneau, R. K. Strong, and A. Aderem. 2007. A conserved surface on Toll-like receptor 5 recognizes bacterial flagellin. J. Exp. Med. 204:393-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attmannspacher, U., B. E. Scharf, and R. M. Harshey. 2008. FliL is essential for swarming: motor rotation in absence of FliL fractures the flagellar rod in swarmer cells of Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 68:328-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker, S., K. Holt, S. Whitehead, I. Goodhead, T. Perkins, B. Stocker, J. Hardy, and G. Dougan. 2007. A linear plasmid truncation induces unidirectional flagellar phase change in H:z66 positive Salmonella Typhi. Mol. Microbiol. 66:1207-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barken, K. B., S. J. Pamp, L. Yang, M. Gjermansen, J. J. Bertrand, M. Klausen, M. Givskov, C. B. Whitchurch, J. N. Engel, and T. Tolker-Nielsen. 2008. Roles of type IV pili, flagellum-mediated motility and extracellular DNA in the formation of mature multicellular structures in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2331-2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumler, A. J., R. M. Tsolis, and F. Heffron. 1996. The lpf fimbrial operon mediates adhesion of Salmonella typhimurium to murine Peyer's patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:279-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergman, M. A., L. A. Cummings, R. C. Alaniz, L. Mayeda, I. Fellnerova, and B. T. Cookson. 2005. CD4+-T-cell responses generated during murine Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection are directed towards multiple epitopes within the natural antigen FliC. Infect. Immun. 73:7226-7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boddicker, J. D., N. A. Ledeboer, J. Jagnow, B. D. Jones, and S. Clegg. 2002. Differential binding to and biofilm formation on, HEp-2 cells by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is dependent upon allelic variation in the fimH gene of the fim gene cluster. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1255-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonifield, H. R., and K. T. Hughes. 2003. Flagellar phase variation in Salmonella enterica is mediated by a posttranscriptional control mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 185:3567-3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckley, J. T., R. McLeod, and J. Frohlich. 1984. Action of a microbial glycerophospholipid:cholesterol acyltransferase on plasma from normal and LCAT-deficient subjects. J. Lipid Res. 25:913-918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budiarti, S., Y. Hirai, J. Minami, S. Katayama, T. Shimizu, and A. Okabe. 1991. Adherence to HEp-2 cells and replication in macrophages of Salmonella derby of human origin. Microbiol. Immunol. 35:111-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler, S. M., and A. Camilli. 2005. Going against the grain: chemotaxis and infection in Vibrio cholerae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:611-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler, T., W. R. Bell, J. Levin, N. N. Linh, and K. Arnold. 1978. Typhoid fever. Studies of blood coagulation, bacteremia, and endotoxemia. Arch. Intern. Med. 138:407-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caiazza, N. C., and G. A. O'Toole. 2003. Alpha-toxin is required for biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 185:3214-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chilcott, G. S., and K. T. Hughes. 2000. Coupling of flagellar gene expression to flagellar assembly in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:694-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costerton, J. W., Z. Lewandowski, D. E. Caldwell, D. R. Korber, and H. M. Lappin-Scott. 1995. Microbial biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:711-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawford, R. W., D. L. Gibson, W. W. Kay, and J. S. Gunn. 2008. Identification of a bile-induced exopolysaccharide required for Salmonella biofilm formation on gallstone surfaces. Infect. Immun. 76:5341-5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crump, J. A., S. P. Luby, and E. D. Mintz. 2004. The global burden of typhoid fever. Bull. World Health Organ. 82:346-353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummings, L. A., W. D. Wilkerson, T. Bergsbaken, and B. T. Cookson. 2006. In vivo, fliC expression by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is heterogeneous, regulated by ClpX, and anatomically restricted. Mol. Microbiol. 61:795-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danese, P. N., L. A. Pratt, and R. Kolter. 2000. Exopolysaccharide production is required for development of Escherichia coli K-12 biofilm architecture. J. Bacteriol. 182:3593-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davey, M. E., and G. A. O'Toole. 2000. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:847-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies, D. G., A. M. Chakrabarty, and G. G. Geesey. 1993. Exopolysaccharide production in biofilms: substratum activation of alginate gene expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1181-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dean, G. E., R. M. Macnab, J. Stader, P. Matsumura, and C. Burks. 1984. Gene sequence and predicted amino acid sequence of the motA protein, a membrane-associated protein required for flagellar rotation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 159:991-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Vries, N., K. A. Zwaagstra, J. H. Huis in't Veld, F. van Knapen, F. G. van Zijderveld, and J. G. Kusters. 1998. Production of monoclonal antibodies specific for the i and 1,2 flagellar antigens of Salmonella typhimurium and characterization of their respective epitopes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:5033-5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deziel, E., Y. Comeau, and R. Villemur. 2001. Initiation of biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 57RP correlates with emergence of hyperpiliated and highly adherent phenotypic variants deficient in swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities. J. Bacteriol. 183:1195-1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dibb-Fuller, M. P., E. Allen-Vercoe, C. J. Thorns, and M. J. Woodward. 1999. Fimbriae- and flagella-mediated association with and invasion of cultured epithelial cells by Salmonella enteritidis. Microbiology 145:1023-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dutta, U., P. K. Garg, R. Kumar, and R. K. Tandon. 2000. Typhoid carriers among patients with gallstones are at increased risk for carcinoma of the gallbladder. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 95:784-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ehrbar, K., and W. D. Hardt. 2005. Bacteriophage-encoded type III effectors in Salmonella enterica subspecies 1 serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Genet. Evol. 5:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franchi, L., A. Amer, M. Body-Malapel, T. D. Kanneganti, N. Ozoren, R. Jagirdar, N. Inohara, P. Vandenabeele, J. Bertin, A. Coyle, E. P. Grant, and G. Nunez. 2006. Cytosolic flagellin requires Ipaf for activation of caspase-1 and interleukin 1beta in salmonella-infected macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 7:576-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fraser, G. M., B. Gonzalez-Pedrajo, J. R. Tame, and R. M. Macnab. 2003. Interactions of FliJ with the Salmonella type III flagellar export apparatus. J. Bacteriol. 185:5546-5554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frye, J., J. E. Karlinsey, H. R. Felise, B. Marzolf, N. Dowidar, M. McClelland, and K. T. Hughes. 2006. Identification of new flagellar genes of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 188:2233-2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garner, M. J., R. D. Hayward, and V. Koronakis. 2002. The Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 secretion system directs cellular cholesterol redistribution during mammalian cell entry and intracellular trafficking. Cell. Microbiol. 4:153-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giron, J. A., A. G. Torres, E. Freer, and J. B. Kaper. 2002. The flagella of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli mediate adherence to epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 44:361-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gross, M., S. E. Cramton, F. Gotz, and A. Peschel. 2001. Key role of teichoic acid net charge in Staphylococcus aureus colonization of artificial surfaces. Infect. Immun. 69:3423-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho, T. D., and J. M. Slauch. 2001. OmpC is the receptor for Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-2 bacteriophages of Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 183:1495-1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber, B., K. Riedel, M. Kothe, M. Givskov, S. Molin, and L. Eberl. 2002. Genetic analysis of functions involved in the late stages of biofilm development in Burkholderia cepacia H111. Mol. Microbiol. 46:411-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hufnagel, M., S. Koch, R. Creti, L. Baldassarri, and J. Huebner. 2004. A putative sugar-binding transcriptional regulator in a novel gene locus in Enterococcus faecalis contributes to production of biofilm and prolonged bacteremia in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 189:420-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hung, D. T., J. Zhu, D. Sturtevant, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2006. Bile acids stimulate biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 59:193-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Idone, V., S. Brendtro, R. Gillespie, S. Kocaj, E. Peterson, M. Rendi, W. Warren, S. Michalek, K. Krastel, D. Cvitkovitch, and G. Spatafora. 2003. Effect of an orphan response regulator on Streptococcus mutans sucrose-dependent adherence and cariogenesis. Infect. Immun. 71:4351-4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikeda, J. S., C. K. Schmitt, S. C. Darnell, P. R. Watson, J. Bispham, T. S. Wallis, D. L. Weinstein, E. S. Metcalf, P. Adams, C. D. O'Connor, and A. D. O'Brien. 2001. Flagellar phase variation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium contributes to virulence in the murine typhoid infection model but does not influence Salmonella-induced enteropathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 69:3021-3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jefferson, K. K. 2004. What drives bacteria to produce a biofilm? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 236:163-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson, M., I. Zaretskaya, Y. Raytselis, Y. Merezhuk, S. McGinnis, and T. L. Madden. 2008. NCBI BLAST: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W5-W9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karlinsey, J. E., S. Tanaka, V. Bettenworth, S. Yamaguchi, W. Boos, S. I. Aizawa, and K. T. Hughes. 2000. Completion of the hook-basal body complex of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellum is coupled to FlgM secretion and fliC transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1220-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kihara, M., T. Minamino, S. Yamaguchi, and R. M. Macnab. 2001. Intergenic suppression between the flagellar MS ring protein FliF of Salmonella and FlhA, a membrane component of its export apparatus. J. Bacteriol. 183:1655-1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45a.Kim, T.-J., B. M. Young, and G. M. Young. 2008. Effect of flagellar mutations on Yersinia enterocolitica biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5466-5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar, S., S. Kumar, and S. Kumar. 2006. Infection as a risk factor for gallbladder cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 93:633-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai, C. W., R. C. Chan, A. F. Cheng, J. Y. Sung, and J. W. Leung. 1992. Common bile duct stones: a cause of chronic salmonellosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 87:1198-1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landini, P., and A. J. Zehnder. 2002. The global regulatory hns gene negatively affects adhesion to solid surfaces by anaerobically grown Escherichia coli by modulating expression of flagellar genes and lipopolysaccharide production. J. Bacteriol. 184:1522-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.La Ragione, R. M., W. A. Cooley, P. Velge, M. A. Jepson, and M. J. Woodward. 2003. Membrane ruffling and invasion of human and avian cell lines is reduced for aflagellate mutants of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lauriano, C. M., C. Ghosh, N. E. Correa, and K. E. Klose. 2004. The sodium-driven flagellar motor controls exopolysaccharide expression in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 186:4864-4874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ledeboer, N. A., and B. D. Jones. 2005. Exopolysaccharide sugars contribute to biofilm formation by Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium on HEp-2 cells and chicken intestinal epithelium. J. Bacteriol. 187:3214-3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lejeune, P. 2003. Contamination of abiotic surfaces: what a colonizing bacterium sees and how to blur it. Trends Microbiol. 11:179-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levine, M. M., R. E. Black, and C. Lanata. 1982. Precise estimation of the numbers of chronic carriers of Salmonella typhi in Santiago, Chile, an endemic area. J. Infect. Dis. 146:724-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewis, K. 2001. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:999-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewis, K. 2007. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:48-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lillehoj, E. P., B. T. Kim, and K. C. Kim. 2002. Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellin as an adhesin for Muc1 mucin. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 282:L751-L756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu, X., and P. Matsumura. 1995. An alternative sigma factor controls transcription of flagellar class-III operons in Escherichia coli: gene sequence, overproduction, purification and characterization. Gene 164:81-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma, L., M. Conover, H. Lu, M. R. Parsek, K. Bayles, and D. J. Wozniak. 2009. Assembly and development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mah, T. F., B. Pitts, B. Pellock, G. C. Walker, P. S. Stewart, and G. A. O'Toole. 2003. A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature 426:306-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McClaine, J. W., and R. M. Ford. 2002. Characterizing the adhesion of motile and nonmotile Escherichia coli to a glass surface using a parallel-plate flow chamber. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 78:179-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McMurry, J. L., J. S. Van Arnam, M. Kihara, and R. M. Macnab. 2004. Analysis of the cytoplasmic domains of Salmonella FlhA and interactions with components of the flagellar export machinery. J. Bacteriol. 186:7586-7592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McSweegan, E., and R. I. Walker. 1986. Identification and characterization of two Campylobacter jejuni adhesins for cellular and mucous substrates. Infect. Immun. 53:141-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Merritt, J. H., K. M. Brothers, S. L. Kuchma, and G. A. O'Toole. 2007. SadC reciprocally influences biofilm formation and swarming motility via modulation of exopolysaccharide production and flagellar function. J. Bacteriol. 189:8154-8164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mey, A. R., S. A. Craig, and S. M. Payne. 2005. Characterization of Vibrio cholerae RyhB: the RyhB regulon and role of ryhB in biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 73:5706-5719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miao, E. A., M. Brittnacher, A. Haraga, R. L. Jeng, M. D. Welch, and S. I. Miller. 2003. Salmonella effectors translocated across the vacuolar membrane interact with the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Microbiol. 48:401-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Minamino, T., R. Chu, S. Yamaguchi, and R. M. Macnab. 2000. Role of FliJ in flagellar protein export in Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 182:4207-4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Monds, R. D., and G. A. O'Toole. 2009. The developmental model of microbial biofilms: ten years of a paradigm up for review. Trends Microbiol. 17:73-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moorthy, S., and P. I. Watnick. 2004. Genetic evidence that the Vibrio cholerae monolayer is a distinct stage in biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 52:573-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nawabi, P., D. M. Catron, and K. Haldar. 2008. Esterification of cholesterol by a type III secretion effector during intracellular Salmonella infection. Mol. Microbiol. 68:173-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nuccio, S. P., D. Chessa, E. H. Weening, M. Raffatellu, S. Clegg, and A. J. Baumler. 2007. SIMPLE approach for isolating mutants expressing fimbriae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:4455-4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ohnishi, K., K. Kutsukake, H. Suzuki, and T. Iino. 1990. Gene fliA encodes an alternative sigma factor specific for flagellar operons in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Gen. Genet 221:139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 28:449-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 30:295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pratt, L. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli biofilm formation: roles of flagella, motility, chemotaxis and type I pili. Mol. Microbiol. 30:285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prigent-Combaret, C., G. Prensier, T. T. Le Thi, O. Vidal, P. Lejeune, and C. Dorel. 2000. Developmental pathway for biofilm formation in curli-producing Escherichia coli strains: role of flagella, curli and colanic acid. Environ. Microbiol. 2:450-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prouty, A. M., I. E. Brodsky, J. Manos, R. Belas, S. Falkow, and J. S. Gunn. 2004. Transcriptional regulation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium genes by bile. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 41:177-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Prouty, A. M., and J. S. Gunn. 2003. Comparative analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium biofilm formation on gallstones and on glass. Infect. Immun. 71:7154-7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Prouty, A. M., W. H. Schwesinger, and J. S. Gunn. 2002. Biofilm formation and interaction with the surfaces of gallstones by Salmonella spp. Infect. Immun. 70:2640-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pruss, B. M., C. Besemann, A. Denton, and A. J. Wolfe. 2006. A complex transcription network controls the early stages of biofilm development by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:3731-3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rochon, M., and U. Romling. 2006. Flagellin in combination with curli fimbriae elicits an immune response in the gastrointestinal epithelial cell line HT-29. Microbes Infect. 8:2027-2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rudner, X. L., L. D. Hazlett, and R. S. Berk. 1992. Systemic and topical protection studies using Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagella in an ocular model of infection. Curr. Eye Res. 11:727-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saijo-Hamano, Y., K. Imada, T. Minamino, M. Kihara, R. M. Macnab, and K. Namba. 2005. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of FlhA, a membrane-protein subunit of the bacterial flagellar type III protein-export apparatus. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 61:599-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saini, S., J. A. Pearl, and C. V. Rao. 2009. Role of FimW, FimY, and FimZ in regulating the expression of type I fimbriae in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 191:3003-3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sauer, K., A. K. Camper, G. D. Ehrlich, J. W. Costerton, and D. G. Davies. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays multiple phenotypes during development as a biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 184:1140-1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schmid, M. B., and J. R. Roth. 1983. Genetic methods for analysis and manipulation of inversion mutations in bacteria. Genetics 105:517-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schoenhals, G. J., and R. M. Macnab. 1999. FliL is a membrane-associated component of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella. Microbiology 145:1769-1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Silverman, M., J. Zieg, M. Hilmen, and M. Simon. 1979. Phase variation in Salmonella: genetic analysis of a recombinational switch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:391-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Simon, R., and C. E. Samuel. 2008. Interleukin-1 beta secretion is activated comparably by FliC and FljB flagellins but differentially by wild-type and DNA adenine methylase-deficient salmonella. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 28:661-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stewart, P. S., and M. J. Franklin. 2008. Physiological heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stoodley, P., K. Sauer, D. G. Davies, and J. W. Costerton. 2002. Biofilms as complex differentiated communities. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:187-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Surette, M. G., and B. L. Bassler. 1999. Regulation of autoinducer production in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 31:585-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Svensater, G., J. Welin, J. C. Wilkins, D. Beighton, and I. R. Hamilton. 2001. Protein expression by planktonic and biofilm cells of Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 205:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Teplitski, M., A. Al-Agely, and B. M. Ahmer. 2006. Contribution of the SirA regulon to biofilm formation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbiology 152:3411-3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thomas, D., D. G. Morgan, and D. J. DeRosier. 2001. Structures of bacterial flagellar motors from two FliF-FliG gene fusion mutants. J. Bacteriol. 183:6404-6412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thomas, D. R., N. R. Francis, C. Xu, and D. J. DeRosier. 2006. The three-dimensional structure of the flagellar rotor from a clockwise-locked mutant of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 188:7039-7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tinker, J. K., L. S. Hancox, and S. Clegg. 2001. FimW is a negative regulator affecting type 1 fimbrial expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 183:435-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Toledo-Arana, A., J. Valle, C. Solano, M. J. Arrizubieta, C. Cucarella, M. Lamata, B. Amorena, J. Leiva, J. R. Penades, and I. Lasa. 2001. The enterococcal surface protein, Esp, is involved in Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4538-4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Uchiya, K., and T. Nikai. 2008. Salmonella virulence factor SpiC is involved in expression of flagellin protein and mediates activation of the signal transduction pathways in macrophages. Microbiology 154:3491-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ueno, T., K. Oosawa, and S. Aizawa. 1992. M ring, S ring and proximal rod of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium are composed of subunits of a single protein, FliF. J. Mol. Biol. 227:672-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vaudaux, P. E., P. Francois, R. A. Proctor, D. McDevitt, T. J. Foster, R. M. Albrecht, D. P. Lew, H. Wabers, and S. L. Cooper. 1995. Use of adhesion-defective mutants of Staphylococcus aureus to define the role of specific plasma proteins in promoting bacterial adhesion to canine arteriovenous shunts. Infect. Immun. 63:585-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Reference deleted.

- 102.Watnick, P., and R. Kolter. 2000. Biofilm, city of microbes. J. Bacteriol. 182:2675-2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Watnick, P. I., C. M. Lauriano, K. E. Klose, L. Croal, and R. Kolter. 2001. The absence of a flagellum leads to altered colony morphology, biofilm development and virulence in Vibrio cholerae O139. Mol. Microbiol. 39:223-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wen, Z. T., and R. A. Burne. 2002. Functional genomics approach to identifying genes required for biofilm development by Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1196-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Whiteley, M., M. G. Bangera, R. E. Bumgarner, M. R. Parsek, G. M. Teitzel, S. Lory, and E. P. Greenberg. 2001. Gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature 413:860-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Worku, M. L., Q. N. Karim, J. Spencer, and R. L. Sidebotham. 2004. Chemotactic response of Helicobacter pylori to human plasma and bile. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:807-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yildiz, F. H., and G. K. Schoolnik. 1999. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:4028-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.