Abstract

Fifteen nonrepetitive ampicillin-resistant Salmonella spp. were identified among 91 Salmonella sp. isolates during nationwide surveillance of Salmonella in waste from 131 chicken farms during 2006 and 2007. Additional phenotyping and genetic characterization of these 15 isolates by using indicator cephalosporins demonstrated that resistance to ampicillin and reduced susceptibility to cefoxitin in three isolates was caused by TEM-1 and DHA-1 β-lactamases. Plasmid profiling and Southern blot analysis of these three DHA-1-positive Salmonella serovar Indiana isolates and previously reported unrelated clinical isolates of DHA-1-positive Salmonella serovar Montevideo, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli from humans and swine indicated the involvement of the large-size plasmid. Restriction enzyme digestion of the plasmids from the transconjugants showed variable restriction patterns except for the two Salmonella serovar Indiana isolates identified in this study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the presence of the DHA-1 gene among Salmonella spp. of animal origin.

Nontyphoidal Salmonella (NTS) strains are a significant cause of gastrointestinal infections of food origin. These microbes are a heterogeneous group of medically important Gram-negative bacteria and can infect a wide range of animals, including humans (3, 6, 9-11, 25).

Currently, no antimicrobial therapies are recommended for the treatment of NTS infection unless a patient is of extreme age, has an underlying disease, or is infected with an invasive Salmonella sp. However, the use of antibiotics in treatment of clinical enteric infection has been heavily compromised by emerging multidrug-resistant microbes (4, 17, 18, 23). In particular, resistance due to extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and AmpC β-lactamases is of special concern as these enzymes confer resistance to some of the front-line antibiotics used to treat enteric infection in humans and animals (4, 13, 14, 19).

Four classes of β-lactamases are known to confer resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Among these, plasmid-mediated class A and class C β-lactamases have been frequently reported, whereas class B and class D β-lactamases are relatively rare (4). TEM and SHV enzymes of class A β-lactamases are generally found in Gram-negative bacteria and are derived by one or more amino acid substitutions around the active site of the enzyme that is responsible for the ESBL phenotype (4). Recently, the CTX-M enzyme of class A β-lactamases has been increasingly reported from enteric microbes, like Salmonella and Escherichia coli (4, 5, 9, 15). These have greater activity against cefotaxime than do other oxyimino-β-lactam substrates, like ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, or cefepime (4, 5). Plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases, like DHA and CMY, are not inhibited by clavulanic acid and have been isolated from a wide variety of clinical and community-acquired microbes (2, 4, 13, 14, 16). These β-lactamases are native to the chromosomes of many Gram-negative bacilli but are missing in some genera, like Salmonella (4). The majority of β-lactamases reported in Salmonella to date have been derived from human clinical isolates, and only limited information is available regarding Salmonella spp. derived from farm animals, although isolates from both humans and animals are of clinical and epidemiological importance (4, 15, 25).

In light of this knowledge gap, our study focused on assessing the distribution of Salmonella serovars in poultry farms in South Korea. Subsequently, isolates were analyzed for resistance to antibiotics commonly used in farms. Phenotypic and genetic characteristics of ampicillin-resistant Salmonella isolates were tested to gain insight into what β-lactamases were prevalent among these strains. We also characterized DHA-1-associated plasmids in these Salmonella spp. and compared them with clinical isolates of Salmonella, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli from humans and from swine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 91 Salmonella isolates were included in the present study. The isolates were collected from May 2006 to September 2007 in the course of a nationwide surveillance that included six provinces (Gyeonggi, Chungbuk, Chungnam, Jeonbuk, Jeonnam, and Jeju). The surveillance was carried out in an effort to identify Salmonella isolates from chicken farms (n = 131) by the National Veterinary Research and Quarantine Service (NVRQS) of South Korea. Isolates were recovered from egg shells, boots, water, and feed samples (5 g) preenriched in 45 ml buffered peptone water (Difco Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ), at 37°C for 18 h. Then, 0.1 ml of the culture was transferred into 10 ml of Rappaport-Vassiliadis broth (RV broth; Merck & Co., Inc., NJ) and was incubated overnight at 42°C. The RV broth samples were streaked onto Ramback agar (Merck & Co.) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Suspected colonies were confirmed to be Salmonella spp. by using Vitek (Vitek System; bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). All Salmonella isolates were serotyped by the Kauffman-White scheme using Salmonella O and H antisera according to the procedures described by the manufacturers (BD, MD; Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan). Once identified, each bacterial culture was maintained in Trypticase soy broth (TSB; Difco) and mixed with glycerin (20%) (Shinyo Pure Chemicals Co. Ltd., Japan) and stored at −80°C for further analysis.

DHA-1-positive Salmonella enterica serovar Montevideo clinical isolates kindly provided by K. Y. Lee (9), single samples of E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolated from swine (20), and two K. pneumoniae clinical isolates (10252 and 10255) obtained from the Korean Type Culture Collection (KTCC), all of which contain the DHA-1 gene, were also included in this study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test.

MICs were determined by broth microdilution methods according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (7). The antimicrobial agents used were ampicillin, amoxicillin, apramycin, ceftiofur, cephalothin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, enrofloxacin, florfenicol, gentamicin, nalidixic acid, neomycin, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, and trimethoprim. E. coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used for quality control experiments. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration that completely inhibited growth. The MIC50 and MIC90 were defined as the antimicrobial concentrations that inhibited growth of 50 and 90% of the strains, respectively.

Isolates showing reduced susceptibility to ampicillin and/or ceftiofur were further investigated for ESBL phenotypes by double-disk diffusion tests using three indicator cephalosporins—cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and cefoxitin alone and in combination with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (8). MICs were determined for the isolates showing complete or decreased inhibition zone diameters for these antimicrobials.

PCR and sequencing of β-lactamase genes.

We targeted class A (TEM, SHV, and CTXM) β-lactamases, AmpC β-lactamases as described by Pérez-Pérez and Hanson (19), class D (OXA) β-lactamases, and PSE-1 β-lactamases that have been reported to contribute to cephalosporin resistance in South Korea (9, 17, 21, 24). Oligonucleotide primer sets and PCR conditions used for amplification of all of these genes except CTX-M (5′-CTGGAGAAAAGCAGCGGAG-3′ and 5′-GTAAGCTGACGCAACGTCCTG-3′; GenBank accession no. FJ424733) and OXA-F (5′-ATGAAAAACACAATACATATCAAC-3′ and 5′-TTCCTGTAAGTGCGGACAC-3′; GenBank accession no. J02967) were as described in our previous studies (21, 22). E. coli (E/123), K. pneumoniae (K/14), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 (ATCC 2501) (21, 22), and S. Montevideo (10) were used as the positive control. Amplified PCR products of expected sizes were subjected to direct sequencing by an automatic sequencer and dye termination sequencing system (Macrogen Co., South Korea). A BLAST search for homologous sequences was conducted in the GenBank database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Conjugation assays.

Mixed broth culture mating was performed as described previously with E. coli J53AzR (resistant to azide) as a recipient strain to observe the transferability of cefoxitin resistance (20). Briefly, a single colony of the donor and recipient strains grown in TSB were mixed and incubated at 37°C for 20 h. MacConkey agar supplemented with sodium azide (200 μg/ml) and cefoxitin (2 μg/ml) was used to select for transconjugants.

Plasmid profiling and DNA hybridization.

A single colony of DHA-1-producing strains (poultry, humans, and swine) and their transconjugants that were confirmed by PCR was picked from MacConkey agar plates and cultured overnight in TSB. Plasmid DNA was extracted using a plasmid midi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) by following the manufacturer's protocol. DNA transfer and hybridization were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX). Plasmid DNA from isolates was electrophoresed through agarose and transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, England). The DHA-1 PCR product was labeled using the BrightStar psoralen-biotin nonisotopic labeling kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, Texas) and used as a probe to detect the DHA-1 sequence in the plasmid DNA of isolates. Detection was performed using the BrightStar BioDetect nonisotopic detection kit (Ambion Inc.). Likewise, plasmids from the transconjugants were digested with EcoRI and HindIII restriction enzymes to observe the restriction patterns.

RESULTS

Distribution of Salmonella serotypes.

In this study, a wide variety of Salmonella serotypes were identified among samples from poultry farms in South Korea. Overall, 91 Salmonella isolates, representing 17 different serotypes, were identified from four provinces: Gyeonggi, Chungbuk, Chungnam, and Jeonnam. S. enterica serovar Enteritidis was the most frequently identified serotype, accounting for 37.3% of the samples. Other frequently identified serotypes included Salmonella serovar Virchow (18.6%), followed by Salmonella serovars Indiana (9.8%), Give (5.49%), and Typhimurium and Istanbul (4.3%) (Table 1). Complete identity of two Salmonella isolates (2.1%) that belonged to serogroups B and C1 could not be determined (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Distribution, sources, and antimicrobial resistance phenotypes of Salmonella serotypes isolated from chicken farms in South Korea

| Serotype | Source(s) | Resistance typea | No. of isolates |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. Agona | Feces | No resistance observed | 2 |

| S. Albert | Feces | Su-Tc | 1 |

| S. Augustenborg | Feces | No resistance observed | 1 |

| S. Bareilly | Feces | No resistance observed | 2 |

| S. Dessau | Feces | Na | 2 |

| S. Enteritidis | Feces, eggshell, dead egg yolk, cloaca, liver, water, environmental dust | Amx-Su-Am-Cm-Na-Sm-Tc | 1 |

| Amx-Su-Am-Na-Sm-Tc | 1 | ||

| Amx-Su-Am-Na-Sm-Tc-Eno | 1 | ||

| Cf-Na-Ap-Sm | 1 | ||

| Na | 3 | ||

| Su | 13 | ||

| Su-Cm-Flo-Na-Tm | 3 | ||

| Su-Na-Sm-Tc | 1 | ||

| Su-Na-Tm | 8 | ||

| No resistance observed | 2 | ||

| S. Ferruch | Feces | Su-Na-Sm-Tc-Cip | 1 |

| S. Give | Feces | Su-Cm-Tc-Tm | 3 |

| Su-Sm-Tc | 2 | ||

| S. Haardt | Feces | Amx-Su-Am-Na-Neo-Sm-Tc-Tm | 2 |

| S. Heidelberg | Feces | Su-Na-Ap-Sm-Tm | 1 |

| S. Indiana | Feces | Amx-Su-Am-Cf-Na-Ap-Neo-Sm-Tc-Tm-Cef | |

| Amx-Su-Am-Te | 2 | ||

| Amx-Am-Su-Tm-Cef | 1 | ||

| Amx-Te | 1 | ||

| Amx-Neo-Te | 1 | ||

| No resistance observed | 3 | ||

| S. Infantis | Feces | Sm | 1 |

| No resistance observed | 1 | ||

| S. Istanbul | Feces | Amx-Cf-Sm-Tc | 1 |

| Amx-Te | 1 | ||

| Neo-Tc | 1 | ||

| Tc | 1 | ||

| S. Truro | Egg yolk | Su-Na-Gm | 1 |

| S. Typhimurium | Feces | Amx-Su | 1 |

| No resistance observed | 3 | ||

| S. Virchow | Feces, water, environmental dust, boats, feed | Su-Na-Sm-Tm | 4 |

| Su-Na-Sm-Tm | 8 | ||

| Su-Na-Tm | 1 | ||

| Su-Sm | 4 | ||

| S. Warragul | Feces | Su-Na-Tm | 1 |

| Salmonella spp. (B group; 4,5;1) | Feces | No resistance observed | 1 |

| Salmonella spp. (C1 group; 7;z10) | Feces | Amx-Su-Am-Cf-Sm-Tc-Tm | 1 |

Ampicillin, Am; amoxicillin, Amx; apramycin, Ap; ceftiofur, Cef; cephalothin, Cf; chloramphenicol, Cm; ciprofloxacin, Cip; enrofloxacin, Eno; florfenicol, Flo; gentamicin, Gm; nalidixic acid, Na; neomycin, Neo; streptomycin, Sm; sulfamethoxazole, Su; tetracycline, Tc; and trimethoprim, Tm.

Antibiotic resistance phenotypes.

Among the drugs tested, resistance was most frequently observed for sulfamethoxazole (74.7%), followed by nalidixic acid (63.7%), streptomycin (38.5%), tetracycline (28.6%), and amoxicillin (18.7%). Infrequent resistance was observed for enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin (1.1%) (Table 2). The isolates exhibited highest MICs to sulfamethoxazole, with an MIC50 and MIC90 of >1,024 μg/ml, followed by ampicillin (MIC90, 512 μg/ml) and nalidixic acid and streptomycin (MIC90, >256 μg/ml). Likewise, the lowest MIC90 values and resistance rates were exhibited by ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin followed by ceftiofur (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella sp. isolates (n = 91) from chicken farms in South Korea

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml) |

Resistance (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | Breakpoint | ||

| Amoxicillin | ≤2->1,024 | ≤2 | 1,024 | 32a | 18.7 |

| Ampicillin | ≤4->1,024 | ≤4 | 512 | 32a | 16.5 |

| Apramycin | 2-64 | 4 | 8 | 32c | 3.3 |

| Ceftiofur | ≤0.25->64 | 0.5 | 1 | 8c | 2.2 |

| Cephalothin | ≤1-256 | 4 | 8 | 32a | 4.4 |

| Chloramphenicol | 2->256 | 4 | 8 | 32a | 5.5 |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25-32 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | 4a | 1.1 |

| Enrofloxacin | ≤0.25-2 | ≤0.25 | 1 | 2b | 1.1 |

| Florfenicol | 2->128 | 4 | 8 | 32c | 3.3 |

| Gentamicin | ≤0.5-128 | ≤0.5 | 1 | 8b | 4.4 |

| Nalidixic acid | 2->256 | >256 | >256 | 32a | 63.7 |

| Neomycin | ≤1-256 | ≤1 | 2 | 16c | 5.5 |

| Streptomycin | ≤1->256 | 8 | >256 | 32c | 38.5 |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 8->1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | 512a | 74.7 |

| Tetracycline | ≤1->256 | 2 | 256 | 16a | 28.6 |

| Trimethoprim | ≤1-256 | ≤1 | ≤1 | 16a | 4.4 |

The value was a CLSI (M100-S19; 2009) breakpoint.

The value was a CLSI (M31-A3; 2008) breakpoint.

The Danish Integrated Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring and Research Programme (DANMAP) Report, 2006.

Three out of 15 ampicillin-resistant isolates also exhibited reduced susceptibility to ceftiofur. A disk diffusion test with cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and cefoxitin showed three isolates with a reduced zone diameter for cefoxitin. The zone diameter for the indicator cephalosporins, cefotaxime and ceftazidime, did not change for these isolates in double-disk synergy test performed with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.

Our study showed that 19.78% of the isolates were resistant to three or more antibiotics, 42.8% were resistant to two antimicrobials tested, and no drug resistance was observed in 14.2% of the Salmonella isolates (Table 1).

Analysis of the β-lactamase genes.

The blaTEM-1 gene was amplified in all ampicillin-resistant isolates (n = 15). The identity of the gene in all these isolates was confirmed by sequencing. In addition to TEM-1, the blaDHA-1 gene was amplified in three isolates showing reduced susceptibility to cefoxitin. SHV, CTXM, PSE-1 and OXA β-lactamases were not detected in these ampicillin-resistant Salmonella sp. isolates. The phenotypic and genetic characteristics of all the ampicillin-resistant isolates are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Antibiogram phenotypes and genotypes of Salmonella serovars exhibiting decreased susceptibility to ampicillin and/or indicator cephalosporins

| Serovar | MIC (μg/ml)a |

TEM | Detection of class A, C, and D β-lactamasesb |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | CEF | CTX | CAZ | FOX | SHV | CTXM | PSE-1 | DHA-1 | OXA | ||

| S. Enteritidis | 1,024 | 1 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Enteritidis | 1,024 | 1 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Enteritidis | 1,024 | 0.5 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Haardt | 1,024 | 0.5 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Haardt | 1,024 | 0.5 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Indiana | 1,024 | 0.5 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Indiana | 1,024 | 0.5 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Indiana | 1,024 | 0.5 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Indiana | 1,024 | 0.5 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Indiana | 1,024 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | + | − |

| S. Indiana | 1,024 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | + | − |

| S. Indiana | 1,024 | 64 | 8 | 4 | 4 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | + | − |

| S. Istanbul | 1,024 | 0.25 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| S. Typhimurium | 1,024 | 0.5 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| Salmonella spp. (C1 group; 7;z10) | 1,024 | 0.5 | TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | − | |||

Ampicillin, AMP; ceftiofur, CEF; cefotaxime, CTX; ceftazidime, CAZ; cefoxitin, FOX.

+, detected; −, not detected.

Transferability of cefoxitin resistance.

Conjugation experiments demonstrated the transfer of cefoxitin resistance from six DHA-1-positive isolates (E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolated from swine [20] and S. Montevideo [9], one K. pneumoniae [1025; KTCC], and two S. Indiana isolates) identified in this study. However, cefoxitin resistance was not transferred by one K. pneumoniae isolate (10255; KTCC) and one S. Indiana isolate (MIC, 2 μg/ml). The transfer frequency ranged from 1.2 × 10−3 to 4.2 × 10−5.

Plasmid profiling and DNA hybridization.

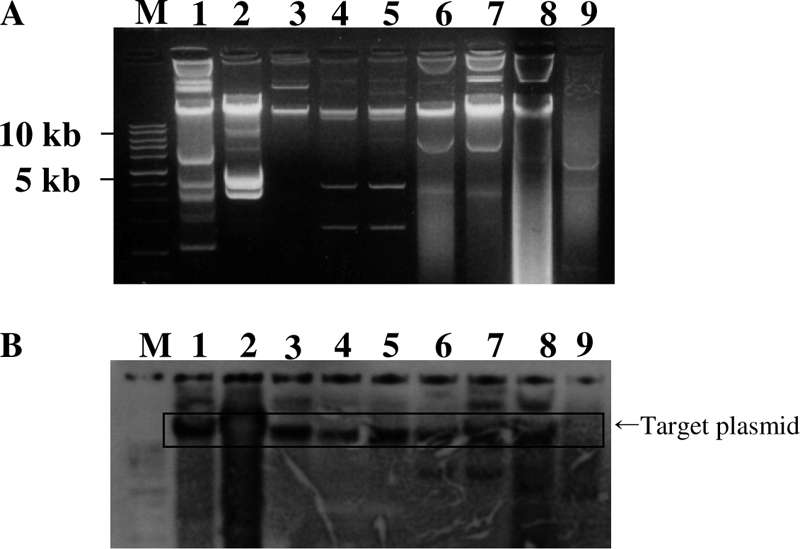

Plasmid profile analysis showed at least one large-size plasmid common to all of these isolates. Likewise, similar blaDHA-1 hybridization patterns were observed among the plasmid DNA extracted from one E. coli isolate and one K. pneumoniae isolate (swine isolates), one S. Montevideo and two K. pneumoniae isolates (human isolates), and the three Salmonella spp. (poultry isolates) (Fig. 1). Plasmids from the transconjugants treated with EcoRI and HindIII restriction enzymes showed different restriction patterns except for the two S. Indiana isolates identified in this study.

FIG. 1.

Plasmid profiling (A) and Southern blot hybridization (B) of DHA-1-positive enteric microbes of human and farm origin. Lane M, 1-kb marker; lane 1, E. coli (swine isolate); lane 2, S. Montevideo (human isolate); lane 3, K. pneumoniae (swine isolate); lanes 4 and 5, K. pneumoniae (human isolates); lanes 6, 7, and 8, S. Indiana (poultry isolates); lane 9, S. Agona (poultry isolates, negative control).

DISCUSSION

S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium are the most frequently reported serovars isolated from humans and animals in South Korea. These two serotypes are also the major causes of Salmonella-associated food-borne illnesses in South Korea (6, 9-11). In this study, we found S. Enteritidis and S. Virchow to be the most frequent serotypes among samples from chicken farms and observed that they were isolated from a wide variety of samples, including egg yolk, egg shell, boots, water, and feed (Table 1). Similarly, S. Indiana, S. Give, and S. Typhimurium were among the 17 different serotypes identified in this study. Our previous study of Salmonella showed that S. Typhimurium was the most prevalent serotype among swine (22). The prevalence of these serotypes among farm animals could be the reason that S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium are the most common causes of food-borne salmonellosis in South Korea. Similar work on Salmonella spp. in the European Union and the United States has described S. Typhimurium and S. Derby to be the most common Salmonella serotypes found on animal farms (1, 3), while in Japan, S. Blockley and S. Hadar were the most commonly identified serotypes in chicken fecal content (1). Adaptation to the local environmental and variation in management practices are possible reasons for the diverse distribution and prevalence of Salmonella serovars among countries.

In recent years, emerging multidrug resistance in Salmonella has complicated the problem of overcoming salmonellosis in humans as well as in animals. In particular, resistance to cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones in Salmonella spp. has limited the available therapeutic options for treatment of clinical salmonellosis (6, 11). This problem has raised great concern regarding the relationship between antimicrobial resistance, antibiotic use in animals, and the transfer of multidrug-resistant Salmonella spp. between animals and humans (10, 25).

The increased antimicrobial resistance to sulfamethoxazole (MIC50 and MIC90, >1,024 μg/ml; resistance, 74.7%), nalidixic acid (MIC50 and MIC90, >256 μg/ml; resistance, 63.7%), and streptomycin (MIC50, 8 μg/ml; MIC90, >256 μg/ml; resistance, 38.5%) in these Salmonella isolates reflects the nature of the selective pressures imposed by the use of these antimicrobial compounds in poultry farms (12). Reports show that these antimicrobials have been used extensively for the treatment of infections and as prophylaxis in chicken feed (12). In particular, indiscriminate use of enrofloxacin in treatment of poultry diseases is likely the cause for the high nalidixic acid resistance seen in Salmonella isolates of poultry origin (8, 12). Most of these nalidixic acid-resistant Salmonella isolates also exhibited MIC90 values of ≤0.25 and 1 μg/ml for ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin, respectively. This drug resistance could be a major public health concern, as fluoroquinolones are important antimicrobial compounds in the treatment of clinical salmonellosis in humans (8).

In this study, nine Salmonella isolates exhibited ampicillin resistance. PCR and sequencing results showed that this resistance was related to TEM-1 β-lactamase, which has been reported to be the most widely distributed β-lactamase in South Korea (18, 21). However, the percentage of ampicillin-resistant isolates (16.4%) identified in this study was comparatively less than those previously reported for Salmonella sp. isolates from swine (64.7%) and humans (39.1%) in South Korea (6, 22). These variations might be due to the nature of antimicrobial selective pressure imposed by the use of different antimicrobials like broad-spectrum cephalosporin (ceftiofur) in swine and extended-spectrum cephalosporin in humans (12, 17, 25).

Among the class C β-lactamases, DHA-1 from clinical enteric microbes of human and animal origin has been reported (9, 16, 17, 21, 23). It was first identified in S. Montevideo in 2003 (10). In subsequent years, DHA-1 was reported to be the dominant AmpC β-lactamase among the Enterobacteriaceae isolated from hospitals in South Korea (14, 17, 23). However, few data are available on ESBLs or AmpC producers in Salmonella from animal origin. In this study, we identified the blaDHA-1 gene in three S. Indiana isolates. Two isolates were from the same chicken farm, and one was isolated from the farm of a different province. These three S. Indiana isolates exhibited reduced susceptibility to the indicator cephalosporins used in the study (Table 3). To our knowledge, this study reports the first blaDHA-1 gene among Salmonella spp. of animal origin.

The plasmid analysis and hybridization pattern of a DHA-1-specific probe of one E. coli isolate and one K. pneumoniae (swine isolate), one S. Montevideo, and two K. pneumoniae (human isolates), and three S. Indiana (poultry isolates) isolates indicated that the blaDHA-1 gene might be carried on the large-size plasmids of enteric microbes of human and animal origin included in this study (Fig. 1). These plasmids except for the K. pneumoniae (10255; KTCC) isolates and one S. Indiana isolate (MIC, 2 μg/ml) carrying the blaDHA-1 gene were transferable by broth conjugation experiment (10, 21). Restriction enzyme digestion profile of the plasmid from transconjugants of the unrelated clinical isolates from human and farm origin showed different restriction patterns except for the two S. Indiana isolates that shared a common restriction pattern for both EcoRI and HindIII. Interestingly, these S. Indiana isolates were from the poultry farms located in different provinces. Thus, from these observations, it could be inferred that promiscuous plasmids of variable and closely related types, carrying the blaDHA-1 gene, could be in circulation among different clones and serotypes of Enterobacteriaceae in South Korea. Our finding is in line with other studies that have reported the involvement of the closely related plasmids carrying ESBL and AmpC genes in different species of Enterobacteriaceae (2, 21, 24, 25). However, since the conjugation experiment carried out in this and other previous experiments failed to demonstrate any transfer of plasmid carrying DHA-1 in some of enteric microbes (17, 21), clonal spread and horizontal transfer could be the other possible mechanisms for the spread of DHA-1 β-lactamases among enteric microbes of farm origin.

In summary, our study identified different Salmonella spp. among chicken farms in South Korea. This information might be helpful for tracking the sources of food-borne infections and designing preventive measures against nontyphoidal Salmonella infection, especially that caused by S. Enteritidis, which is an egg-transmitted pathogen of poultry and also has human health implications through consumption of contaminated poultry products. In addition, coexpression of TEM-1 and DHA-1 β-lactamases in Salmonella spp. of farm origin may complicate its detection and facilitate the further spread of DHA-1 β-lactamases among zoonotic enteric microbes of farm origin (2, 13, 17, 24).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant funded by the Korean Research Foundation (KRF-2006-21-E00011, KRF-2006-005-J502901), a BK-21 grant, and a Bio-Green 21 grant (20070401-034-009-007-01-00).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiba, M., T. Ohya, M. Mitsumori, T. Sameshima, and M. Nakazawa. 1996. Serotype of Salmonella choleraesuis ssp. choleraesuis isolated from domestic animals. Bull. Natl. Inst. Anim. Health 103:43-48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez, M., J. H. Tran, N. Chow, and G. A. Jacoby. 2004. Epidemiology of conjugative plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:533-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beloeil, P. A., P. Fravalo, C. Fablet, J. P. Jolly, E. Eveno, Y. Hascoet, C. Salvat, G. Chauvin, and F. Madec. 2004. Risk factors for Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica shedding by market-age pigs in French farrow-to-finish herds. Prev. Vet. Med. 63:103-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, P. A. 2001. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:933-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantón, R., and T. M. Coque. 2006. The CTX-M beta-lactamase pandemic. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:466-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi, S. H., J. H. Woo, J. E. Lee, S. J. Park, E. J. Cho, Y. G. Kwak, M. N. Kim, M. S. Choi, N. Y. Lee, B. K. Lee, N. J. Kim, J. Y. Jeong, J. Ryu, and Y. S. Kim. 2005. Increasing incidence of quinolone resistance in human nontyphoid Salmonella enterica isolates in Korea and mechanisms involved in quinolone resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:1111-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk dilution susceptibility test for bacteria isolated from animals, 3rd ed. Approved standard M31-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 8.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 19th informational supplement. M100-S19. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 9.González-Sanz, R., S. Herrera-León, M. de la Fuente, M. Arroyo, and M. A. Echeita. 2009. Emergence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and AmpC-type beta-lactamases in human Salmonella isolated in Spain from 2001 to 2005. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:1181-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, J. Y., Y. J. Park, S. O. Lee, W. K. Song, S. H. Jeong, Y. A. Yoo, and K. Y. Lee. 2004. Case report: bacteremia due to Salmonella enterica serotype Montevideo producing plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamase (DHA-1). Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 34:214-217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, S., Y. G. Choi, J. W. Eom, T. J. Oh, K. S. Lee, S. H. Kim, E. T. Lee, M. S. Park, H. B. Oh, and B. K. Lee. 2007. An outbreak of Salmonella enterica serovar Othmarschen at funeral service in Guri-si, South Korea. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 60:412-413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korea Food and Drug Administration. 2005. Establishment of control system of antibiotics for livestocks. Korea Food and Drug Administration, Seoul, South Korea.

- 13.Lee, K., M. Lee, J. H. Shin, M. H. Lee, S. H. Kang, A. J. Park, D. Yong, and Y. Chong. 2006. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. Microb. Drug Resist. 12:44-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, K. W., D. G. Yong, Y. S. Choi, J. H. Yum, J. M. Kim, N. Woodford, D. M. Livermore, and Y. Chong. 2007. Reduced imipenem susceptibility in Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates with plasmid-mediated CMY-2 and DHA-1 beta-lactamases co-mediated by porin loss. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29:201-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, X. Z., M. Mehrotra, S. Ghimire, and L. Adewoye. 2007. Beta-lactam resistance and beta-lactamases in bacteria of animal origin. Vet. Microbiol. 121:197-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liebana, E., M. Batchelor, F. A. Clifton-Hadley, R. H. Davies, K. L. Hopkins, and E. J. Threlfall. 2004. First report of Salmonella isolates with the DHA-1 AmpC beta-lactamase in the United Kingdom. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pai, H. J., C. I. Kang, J. H. Byeon, D. L. Lee, W. B. Park, H. B. Kim, E. C. Kim, M. D. Oh, and K. W. Choe. 2004. Epidemiology and clinical features of bloodstream infections caused by AmpC-type-beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3720-3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pai, H. J., S. Lyu, J. H. Lee, J. Kim, Y. Kwon, J. W. Kim, and K. W. Choe. 1999. Survey of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: prevalence of TEM-52 in Korea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1758-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pérez-Pérez, F. J., and N. D. Hanson. 2002. Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase gene in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2153-2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rayamajhi, N., S. B. Cha, M. L. Kang, S. I. Lee, H. S. Lee, and H. S. Yoo. 2009. Inter- and intraspecies plasmid-mediated transfer of florfenicol resistance in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from swine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:5700-5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rayamajhi, N., S. G. Kang, D. Y. Lee, M. L. Kang, S. I. Lee, K. Y. Park, H. S. Lee, and H. S. Yoo. 2008. Characterization of TEM-, SHV- and AmpC-type beta-lactamases from cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from swine. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 124:183-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rayamajhi, N., S. G. Kang, M. L. Kang, K. Y. Park, H. S. Lee, and H. S. Yoo. 2008. Assessment of antibiotic resistance phenotype and integrons in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolated from swine. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 70:1133-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song, W., J. S. Kim, H. S. Kim, S. H. Jeong, D. Yong, and K. M. Lee. 2006. Emergence of Escherichia coli isolates producing conjugative plasmid-mediated DHA-1 beta-lactamase in a Korean university hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 63:459-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song, W. K., J. S. Kim, H. S. Kim, D. G. Yong, S. H. Jeong, M. J. Park, and K. M. Lee. 2006. Increasing trend in the prevalence of plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae lacking chromosomal ampC gene at a Korean university hospital from 2002-2004. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 55:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winokur, P. L., D. L. Vonstein, L. J. Hoffman, E. K. Uhlenhopp, and G. V. Doern. 2001. Evidence of transfer of CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamase plasmids between Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from food animals to humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2716-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]