Abstract

The root disease take-all, caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici, can be managed by monoculture-induced take-all decline (TAD). This natural biocontrol mechanism typically occurs after a take-all outbreak and is believed to arise from an enrichment of antagonistic populations in the rhizosphere. However, it is not known whether these changes are induced by the monoculture or by ecological rhizosphere conditions due to a disease outbreak and subsequent attenuation. This question was addressed by comparing the rhizosphere microflora of barley, either inoculated with the pathogen or noninoculated, in a microcosm experiment in five consecutive vegetation cycles. TAD occurred in soil inoculated with the pathogen but not in noninoculated soil. Bacterial community analysis using terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism of 16S rRNA showed pronounced population shifts in the successive vegetation cycles, but pathogen inoculation had little effect. To elucidate rhizobacterial dynamics during TAD development, a 16S rRNA-based taxonomic microarray was used. Actinobacteria were the prevailing indicators in the first vegetation cycle, whereas the third cycle—affected most severely by take-all—was characterized by Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Planctomycetes, and Acidobacteria. Indicator taxa for the last cycle (TAD) belonged exclusively to Proteobacteria, including several genera with known biocontrol traits. Our results suggest that TAD involves monoculture-induced enrichment of plant-beneficial taxa.

The root disease take-all, caused by the soilborne ascomycete fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici, has a significant impact on the global production of wheat and barley (23). Usually, take-all is managed by crop rotation, but low disease levels may also be achieved by monoculture-induced disease suppressiveness (13, 50, 61). Indeed, a spontaneous reduction of disease severity can be observed during wheat or barley monoculture after at least one severe outbreak of the disease, a phenomenon called take-all decline (TAD). Disease symptoms then remain at a low level as long as monoculture continues. TAD is related to the enrichment of certain rhizosphere populations antagonistic to the pathogen (13) and parallel changes in G. graminis var. tritici populations (28).

Though TAD is the best-studied example of induced disease suppressiveness (61), knowledge of the mechanisms involved in TAD is fragmentary. Take-all research so far has mainly focused on the role of fluorescent pseudomonads, as they are easy to cultivate and known to be antagonistic to various phytopathogens (21, 35, 62, 63). Several studies have indicated the involvement of other microorganisms in TAD, e.g., Bacillus species and various actinomycetes (3, 26, 45), but none of them has considered the whole bacterial community. Yet, it has been shown that community-based approaches are important in identifying microbial populations potentially involved in suppressiveness (10, 27).

The first community-based assessment was carried out based on molecular fingerprinting and sequencing, and it showed that take-all disease of wheat induced changes in several rhizosphere bacterial populations (39). However, disease-suppressive stages were not included. More recently, the taxonomic microarray-based study of Sanguin et al. (48) revealed multiple changes in the rhizobacterial community of wheat when comparing take-all disease and suppressive stages, which paralleled changes in Pseudomonas populations (46). These differences were attributed to TAD, but it is not known whether they occurred as a result of repeated wheat cropping (leading to enrichment of particular bacterial taxa), a disease outbreak and subsequent attenuation (modifying nutrient conditions on roots), or both.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare the significance of plant succession and take-all disease as environmental factors shaping the rhizobacterial community during TAD. Repeated barley cropping was carried out in microcosms inoculated with G. graminis var. tritici or not inoculated, and the physiologically active bacterial rhizosphere community was monitored using terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (t-RFLP) (32), as well as microarray analysis of 16S rRNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microcosm experiment.

Thirty microcosms (polypropylene tubes; depth, 70 cm; diameter, 15 cm) were filled with 5 cm of expanded clay at the bottom, covered by a water-permeable membrane, and above that 60 cm of untreated soil collected in 2004 from the surface layer of an arable field at the agro-ecological research station of the Helmholtz Zentrum München in Scheyern (Bavaria, Germany; latitude, 48°29′51″N; longitude, 11°26′39″E; elevation, 455 m). The soil was a fine loamy gleyic cambisol (silt, 59%; sand, 21%; clay, 20%) with a pH (CaCl2) of 6.2, 15.6 g kg−1 organic C, and 1.9 g kg−1 total N. In the 3 years preceding the experiment, the field was cropped successively with potatoes, winter wheat, and trefoil-grass.

During the experiment, the soil was fertilized with urea ammonium nitrate at a rate equivalent to 50 kg N ha−1 prior to each vegetation cycle and the soil water content was kept at 60% of the maximum water-holding capacity by irrigation three times per week with tap water. Spring barley (Hordeum vulgare) cv. Barke (Breun, Herzogenaurach, Germany) was grown in monoculture in an uninterrupted succession of five vegetation cycles to stimulate the development of a G. graminis var. tritici-suppressive soil. At the beginning of each cycle, 15 microcosms were inoculated with G. graminis var. tritici. For this purpose, each of the six barley grains sown per tube was placed together with four kernels of fungal inoculum and covered with 0.5 cm of sieved soil. The fungal inoculum was prepared by growing G. graminis var. tritici strain 13 (40) on double-sterilized moist oat kernels for 5 weeks at 20°C (25). The colonized oat grains were air dried in a laminar-flow hood and stored at 4°C until use. In the noninoculated tubes, double-sterilized oat grains were used. After emergence, the number of seedlings was reduced to three. Microcosms were kept at day/night temperatures of 20/15°C with a 15-h photoperiod (photosynthetically active photon flux density of 500 to 600 μmol s−1 m−2). Vegetation periods and sampling times are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Vegetation cycles and sampling dates

| Vegetation cycle | Vegetation period |

Sampling |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start date | End date | Duration (days) | Date | Days after sowing | Growth stage | |

| 1 | 04.03.2005 | 11.07.2005 | 129 | 10.05.2005 | 67 | 60-61 |

| 2 | 27.09.2005 | 09.01.2006 | 104 | 30.11.2005 | 66 | 55-61 |

| 3 | 16.01.2006 | 26.04.2006 | 100 | 16.03.2006 | 59 | 54-61 |

| 4 | 12.05.2006 | 07.08.2006 | 87 | 28.06.2006 | 47 | 61-65 |

| 5 | 29.08.2006 | 18.12.2006 | 111 | 02.11.2006 | 65 | 55-61 |

After each vegetation cycle, the soil from all 15 microcosms per treatment was collected and mixed thoroughly before being returned to the same tubes. Throughout the experiment, inoculated and noninoculated soil and the corresponding microcosms were kept strictly separate to avoid contamination.

Sampling.

In each vegetation cycle, four microcosms per treatment were harvested at growth stage 60 (Table 1) (58). After determining the number of tillers per plant and measuring their lengths, shoots were removed for subsequent dry weight determination. The loosely adhering soil was removed from each root system by shaking. Roots from two plants per microcosm were washed free of soil with tap water and examined for disease symptoms (23); the percentage of the total blackened area per root system was assessed using 11 classes (0 to 5%, 5 to 10%, 10 to 20%, 20 to 30%, 30 to 40%, 40 to 50%, 50 to 60%, 60 to 70%, 70 to 80%, 80 to 90%, and 90 to 100%). The root of the third plant and closely adhering rhizosphere soil were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis. Plants were kept until ripening in the remaining 22 microcosms. Afterwards, shoots were removed but the three root systems were left in the soil to favor pathogen establishment.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis.

For each plant, the entire rhizosphere sample was homogenized using liquid nitrogen prior to the extraction of nucleic acids. Total DNA and RNA were coextracted from 0.5 g (wet weight) of homogenized rhizosphere sample, each in triplicate, following the protocol of Griffiths et al. (19). Nucleic acids were finally resuspended in 30 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated Milli-Q water.

Template DNA was removed from the coextract by treatment with 1 U μg−1 RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantities of extracted nucleic acids and RNA, respectively, were measured with an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). cDNA synthesis was conducted with 0.5 to 0.8 μg template RNA in a 20-μl volume using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as recommended by the supplier but with an increased incubation time of 90 min at 37°C and an additional step of 5 min at 93°C to inactivate the enzyme. RNaseOUT (10 U; Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used as an RNase inhibitor. Aliquots of the finished reverse transcription reaction product were used directly for PCR.

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes, endonuclease restriction, and t-RFLP analysis.

The universal eubacterial primers 27f (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) (11, 41) and 1401r (5′-CGGTGTGTACAAGACCC-3′) (59) were used to obtain 1.4-kb amplicons of the 16S rRNA gene. For t-RFLP analysis, primer 27f was labeled with Cy5 dye. PCR was performed in a total volume of 50 μl containing 50 to 100 ng template cDNA, 0.5 M betaine, 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP; Fermentas Life Sciences, St. Leon-Rot, Germany), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 1× Taq buffer (Invitrogen), and 0.2 μM each primer. PCR was performed in a T3 thermocycler (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany) using an initial denaturation step of 3 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 57°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C and a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) as directed by the supplier.

Restriction enzyme MspI was selected based on in silico t-RFLPs using the program TAP t-RFLP of Ribosomal Database Project II (34). Selection criteria were (i) sufficient separation of bacterial species that previously had been isolated from the microcosm experiment and (ii) terminal restriction fragments (t-RFs) within the size range of the standard used. The labeled PCR product (200 ng) was mixed with 5 U of MspI and 1× reaction buffer Tango (Fermentas Life Sciences) in a final volume of 25 μl. Restriction reaction mixtures were incubated for 6 h at 37°C, followed by 20 min at 65°C for enzyme inactivation. The reaction mixture was purified with the MinElute Reaction Cleanup kit (Qiagen) following the supplier's instructions.

For t-RFLP migration, 2 μl purified restricted PCR product was mixed in triplicate with 0.25 μl of Genome Lab DNA size standard 600 and 27.75 μl of Genome Lab sample loading solution (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany). Samples were overlaid with mineral oil, and DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a CEQ 2000 Genetic Analyzer (Beckman Coulter) using the Frag-4 separation method according to the Genome Lab fragment analysis protocol.

Analysis of t-RFLP profiles and statistical evaluation.

Chromatograms were analyzed with the CEQ 8000 Genetic Analysis System software (Beckman Coulter) using the quartic model as the size-calling algorithm (according to the Genome Lab Fragment Analysis Protocol), with a slope threshold of 1, a relative peak height threshold of 1.0% (relative to the second highest peak), and a confidence level of 95% to identify peaks. Fragments between 60 and 600 bp in length were considered for statistical analysis. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis was done with a binning range of 1 bp. As t-RFs can differ slightly in size, t-RFLP profiles were examined visually to confirm peak size variations of 1 or 2 bp by comparing the respective peaks of all profiles. Since most peaks were present in all samples, peak abundance was used for statistical analysis. Before standardization, the mean value for each t-RF was calculated from the absolute peak heights of the profiles of the three extraction replicates per sample. To account for differences in the overall DNA amount for each sample, the data set was then normalized to the percentage of the total peak height of a sample (38). Prior to principal-component analysis (PCA), t-RFs smaller than 0.25% of the total peak height were excluded from the analysis and a square root transformation was performed (9, 29, 43). The CANOCO 4.5 software package (Microcomputer Power, Ithaca, NY) (55) was utilized to compare t-RFLP profiles by PCA using the covariance matrix. Previously, detrended correspondence analysis of the data set had resulted in a gradient length of <3 (1.528) and thus confirmed the linear distribution of variables that is required for PCA (30). Community similarities were graphed using ordination plots with scaling focused on interspecies correlations. Species scores were not posttransformed. Quantitative factors potentially affecting community structure, including take-all disease symptoms and plant growth parameters, were used as environmental data.

The permutation-based multivariate analysis of variance was conducted with the PerMANOVA software (1, 36) using an experimental design consisting of the two factors vegetation cycle (five levels) and inoculation (two levels) with the null hypothesis “no influence of factors” and a significance level of 0.05 (n = 4 replicates per vegetation cycle and treatment). Both factors were defined as orthogonal and fixed. For each analysis term, 4,999 random permutations of the raw data were conducted to obtain P values (33). Euclidean distance was used as a distance measure (2, 55).

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes and labeling for microarray analysis.

The universal eubacterial primers T7-27f (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ [the T7 sequence is in italics]) and pH (5′-AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA-3′) (11) were used to amplify the 16S rRNA gene from the cDNA samples. Each PCR mixture contained 30 to 60 ng of template cDNA, 1× Expand High Fidelity Polymerase buffer (Roche, Neuilly sur Seine, France), 200 μM each dNTP, 0.5 μM each primer, 2% DMSO, 1.25 μg of T4 G32 protein (Roche), and 3.5 U of Expand High Fidelity Polymerase (Roche) in a final volume of 50 μl. Thermal cycling was done with denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 45 s at 60°C, and 90 s at 72°C and a final elongation for 7 min at 72°C. PCR products were purified with the MinElute PCR Purification kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). DNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically and adjusted to 50 ng μl−1. Fluorescence labeling by in vitro transcription (54), RNA purification, and fragmentation were carried out as described by Sanguin et al. (46).

Microarray analysis.

The taxonomic microarray contained 1,033 probes targeting 19 of 34 bacterial phyla with at least one probe (27). Some phyla, in particular, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes, were targeted at the class, family, genus, and/or species level. Furthermore, the microarray covered most of the bacterial taxa known to include plant-beneficial bacteria (i.e., 90 species in 50 genera).

One slide containing four repetitions of each probe was hybridized per sample. Hybridization, washing, and handling of the slides were carried out as described by Sanguin et al. (46). The slides were scanned at 532 nm with 10-μm resolution using a GeneTac LS IV scanner (Genomic Solutions, Huntingdon, United Kingdom). Images were analyzed with the GenePix 4.01 software (Axon, Union City, CA). Spot quality was visually checked, and spots of poor quality (i.e., the presence of dust, hybridization signal saturation, etc.) were excluded from further analyses as described previously (47). Data filtration was conducted with the R 2.2.0 statistical computing environment (http://www.r-project.org). A given spot was considered hybridized when 80% of the spot pixels had an intensity higher than the median local background pixel intensity plus twice the standard deviation of the local background. Spot intensities (median of the signal minus the background) were subjected to square root transformation and normalized to the percentage of the total intensity signal (47). A probe was considered positive when hybridization signals were superior to the mean signal of the negative controls and at least three of four replicate spots were hybridized (27).

Statistical analysis of microarray data.

Data were treated by between-group analysis (BGA; using PCA-based ordination) with the package ade4 (56) within the R statistical computing environment (http://www.r-project.org) as described by Culhane et al. (16). Three groups were specified according to the three vegetation cycles subjected to microarray analysis. Significance of differences between the groups was analyzed with Monte Carlo tests (P = 0.001) based on 999 permutations (the function “randtest” in R, package ade4). Probes associated with each group were identified from comparison of group mean position and probe position along the ordination axes (16). In addition, significant bioindicator taxa for each vegetation cycle were determined using Indicator Species Analysis (17) and the PC-ORD software, version 5.0.

RESULTS

Development of TAD in the microcosm experiment.

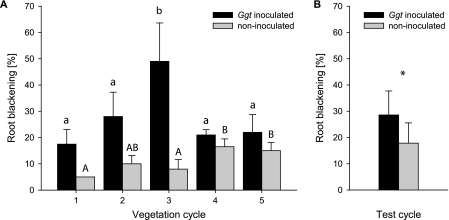

During the first vegetation cycle, the take-all level in the G. graminis var. tritici-inoculated microcosms (18%) was already more than three times as severe as in the noninoculated control (5%, Fig. 1A). Root blackening in the inoculated microcosms reached its maximum in cycle 3 (49%, with up to 80% for individual plants), where roots were quite brittle and broke off easily when sampled, which is typical of advanced take-all infection (4). Shoots were significantly shorter (64 ± 17 [standard deviation] cm) than in the noninoculated microcosms (83 ± 12 cm) during this cycle. In cycles 4 and 5, root blackening was abruptly reduced to about 20%, which was similar to the disease level at the start of the experiment. In parallel, plant growth in these last two cycles was similar to that in cycle 1.

FIG. 1.

Root blackening caused by the take-all fungus in the microcosm experiment, evaluated at the flowering stage. (A) Five consecutive vegetation cycles. Mean values and standard deviations for eight barley root systems per cycle and treatment are shown. Significant differences at P values of <0.05 are represented by lowercase letters (G. graminis var. tritici-inoculated microcosms) and capitals (noninoculated microcosms) according to results from one-way analysis of variance, followed by the Tukey honestly significant difference test. (B) Additional vegetation cycle with the soil from the so-far-noninoculated microcosms. Mean values and standard deviations for 14 barley root systems per treatment are shown. The difference between treatments was significant (P = 0.033; t test for independent random sample), which is indicated by the asterisk.

In the noninoculated microcosms, take-all increased above 10% in cycles 4 and 5 but without causing significant damage (Fig. 1A), which means that neither a take-all outbreak nor TAD was observed. We carried out an additional (sixth) vegetation cycle of barley in this soil, this time after having inoculated G. graminis var. tritici into half of the microcosms. Inoculated plants showed 29% ± 9% root blackening, which was a significantly higher level (t test) than in the noninoculated control (18% ± 8%; Fig. 1B), confirming that noninoculated soil had not developed suppressiveness during the first five cycles.

Comparative effects of barley succession and take-all disease on the rhizobacterial community.

Community analysis was performed using 120 t-RFLP profiles generated from the three technical RNA extraction replicates for each of the 40 rhizosphere samples (i.e., five cycles, two treatments, and four biological replicates). In the compiled t-RFLP data set, 184 individual t-RFs could be identified, 102 of which were present in all samples. Fifty t-RFs were found in at least 30 of the 40 samples. Altogether, 63 t-RFs (out of these 152) exceeded the threshold of 0.25% mean relative abundance and were considered for further statistical analysis. The remaining 32 t-RFs, detected in fewer than 30 samples, were all below the threshold and therefore excluded from the analysis.

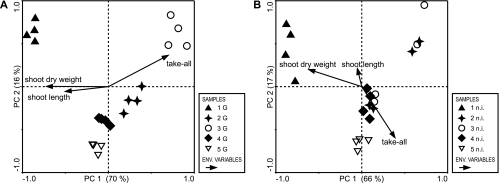

PCA analyses of the G. graminis var. tritici-inoculated and noninoculated systems were conducted. The ordination plot for the inoculated samples showed significant clustering according to the individual vegetation cycles (Fig. 2A). Additionally, pronounced population shifts were detected between all individual vegetation cycles. The largest shift was observed from cycle 1 to cycle 2, which were separated by both the first and second principal components. The first principal component explained 70% of the variance, and a further 16% was explained by the second axis; thus, 86% of the cumulative variance was explained. Root blackening was associated with cycle 3, as expected. Shoot dry weight and shoot length followed the first axis and were almost inversely proportional to infection rates. The ordination plot of the noninoculated soil (explaining 83% of the variance; Fig. 2B) was similar to that of the inoculated samples, except that (i) samples from cycles 2 and 3 were more spread out and (ii) samples from cycles 2 to 4 were rather mixed. Infection data in this system were correlated with axis 2, which explained only 17% of the variance, however. Here, G. graminis var. tritici infestation apparently had little influence on the distribution, which is not surprising considering the low infection rates in the noninoculated soil and the absence of TAD development.

FIG. 2.

PCA of the t-RFLP data set. The ordination plots from the first two principal components (PC) show mean values for three replicates per sample. The percentage of variance explained by the ordination axes is given in parentheses. Symbols illustrate vegetation cycles 1 to 5 of the microcosm experiment; individual points represent the microbial communities associated with discrete root systems. The environmental (ENV.) parameters take-all (root blackening caused by G. graminis var. tritici), shoot dry weight, and shoot length are shown as vectors, indicating the direction of maximum change of the parameter. Vector length indicates the strength of the correlation with the axes. (A) Microcosms inoculated with G. graminis var. tritici. (B) Noninoculated (n.i.) microcosms.

When PCA was done on inoculated and noninoculated samples together, samples from the same cycles were superposed, indicating no effect of G. graminis var. tritici inoculation. This was confirmed by variance analysis using PerMANOVA, which showed also that (i) the vegetation cycle-inoculation interaction was not significant and (ii) the vegetation cycle was a highly significant factor (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

PerMANOVA of 40 t-RFLP profiles of G. graminis var. tritici-inoculated and noninoculated samples from vegetation cycles 1 to 5 based on Euclidian distancesa

| Source | df | SS | MS | F | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation cycle | 4 | 406.5042 | 101.6261 | 32.3614 | 0.0002 |

| Inoculation | 1 | 7.6304 | 7.6304 | 2.4298 | 0.0840 |

| Vegetative cycle × inoculation | 4 | 20.7867 | 5.1967 | 1.6548 | 0.1204 |

| Residual | 30 | 94.2104 | 3.1403 | ||

| Total | 39 | 529.1318 |

Four replicates per vegetation cycle and treatment. df, degrees of freedom; SS, sum of squares; MS, mean of squares; F, Fc statistic.

Comparison of barley cultivation cycles.

Since the vegetation cycle was a significant factor influencing the bacterial community, the individual vegetation cycles were compared in more detail. Pairwise a posteriori tests based on t-RFLP data showed that all of the vegetation cycles differed significantly from one another when considering (i) the two treatments together or (ii) only the inoculated treatment (Table 3). In the noninoculated treatment, however, there was no significant difference among cycles 2, 3, and 4.

TABLE 3.

PerMANOVA of 40 t-RFLP profiles from vegetation cycles 1 to 5 based on Euclidian distancesa

| Comparisonb |

G. graminis var. tritici inoculated + noninoculated |

G. graminis var. tritici inoculated |

Noninoculated |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | P value | t | P value | t | P value | |

| 1 vs 2 | 7.9730 | 0.0004 | 7.4291 | 0.0002 | 4.5848 | 0.0006 |

| 1 vs 3 | 7.0032 | 0.0002 | 7.0541 | 0.0002 | 4.1757 | 0.0004 |

| 1 vs 4 | 8.1843 | 0.0002 | 6.8972 | 0.0002 | 5.0610 | 0.0006 |

| 1 vs 5 | 8.1494 | 0.0002 | 6.2869 | 0.0002 | 5.0965 | 0.0002 |

| 2 vs 3 | 1.8495 | 0.0482 | 2.8908 | 0.0048 | 0.5625 | 0.7126 |

| 2 vs 4 | 3.1156 | 0.0004 | 3.4017 | 0.0018 | 1.8102 | 0.0712 |

| 2 vs 5 | 4.1722 | 0.0002 | 3.8246 | 0.0012 | 2.5498 | 0.0208 |

| 3 vs 4 | 3.8118 | 0.0002 | 4.6251 | 0.0004 | 1.8735 | 0.0594 |

| 3 vs 5 | 4.5767 | 0.0006 | 5.0078 | 0.0008 | 2.5569 | 0.0142 |

| 4 vs 5 | 3.5897 | 0.0002 | 2.9824 | 0.0044 | 2.6175 | 0.0060 |

There were four replicates per vegetation cycle and treatment. P values were obtained using 4,999 permutations of the given permutable units for each term or using 4,999 Monte Carlo samples from the asymptotic permutation distribution (in italics) when there were few possible permutations.

Pairwise a posteriori tests among vegetation cycles using the t statistic.

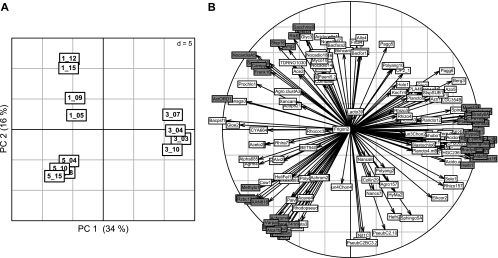

Differences among emblematic vegetation cycles 1 (initial stage), 3 (maximum disease level), and 5 (suppressiveness) in the G. graminis var. tritici-inoculated treatment were confirmed using an alternative methodology based on 16S rRNA microarray hybridization. Indeed, PCA-based BGA of hybridization data enabled the distinction of the three vegetation cycles, as shown in the ordination diagram of the first two principal components (Fig. 3A). The first axis (34% variance) separated cycle 3 from cycles 1 and 5, and the second axis (16%) separated cycle 1 from cycle 5. The vegetation cycles were significantly different according to Monte Carlo test.

FIG. 3.

BGA of microarray data using PCA of bacterial populations from vegetation cycles 1 (initial stage), 3 (maximum disease level), and 5 (suppressiveness), with four replicates each. Ordination plots from the first two principal components (PC) are shown for the samples (A) and the 209 probes giving positive signals (B). The percentage of variance explained by the ordination axes is given in parentheses. In panel B, the 59 indicator probes are highlighted.

Microarray identification of taxa associated with vegetation cycles.

Microarray data were also used to identify the bacterial phylotypes characteristic of the different cycles of barley monoculture in inoculated samples. Of the 1,033 probes present on the microarray, 209 probes hybridized with the 16S rRNA amplicon from rhizosphere cDNA. The number of positive probes per plant was 95 to 123 for cycle 1, 111 to 132 for cycle 3, and 103 to 119 for cycle 5.

From a comparison of group mean position and probe position along the ordination axes (Fig. 3B), the probes associated with each vegetation cycle could be visually estimated (16). The characteristic probes inferred from BGA and confirmed by Indicator Species Analysis (17) are shown in Table 4. Thus, 10 probes were found associated with the initial stage, targeting Actinobacteria (notably, the order Actinomycetales and the genus Nocardioides), Epsilonproteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. In contrast, cycle 3 (maximum disease level) was characterized by as many as 34 probes, comprising various members of the Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma-, Delta-, and Epsilonproteobacteria, as well as Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Planctomycetes, Acidobacteria, and Firmicutes. Strikingly, the 15 probes associated with cycle 5 (disease suppressiveness) targeted exclusively the Proteobacteria, i.e., certain Alphaproteobacteria (such as Rhizobiaceae and relatives, Rhizobium/Agrobacterium, Methylobacterium, Acidiphilium), Betaproteobacteria (e.g., Variovorax, Burkholderia, Alcaligenaceae), and Gammaproteobacteria (Xanthomonadaceae).

TABLE 4.

Indicator species according to BGA and Indicator Species Analysis

| Probea (BGA)b | Microarray signal (10−5)c |

Target taxonomic affiliation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | Cycle 3 | Cycle 5 | Phylum | Class | Family | Target | |

| Cycle 1 (Comp|1|+2) | |||||||

| NocardioA5 (1.317)e | 2,255 | 354 | 1,204 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Norcadioidaceae | Nocardioides |

| Stsp16 (1.215)e | 401 | 34 | 137 | Streptosporangiaceae | Streptosporangium | ||

| ActORD1 (1.161)d | 2,124 | 601 | 1,847 | Actinomycetales | |||

| Sacchps10 (1.150)d | 842 | 282 | 523 | Pseudonocardiaceae | Saccharopolyspora | ||

| Sacchms9 (1.140) | 74 | 0 | 0 | Pseudonocardiaceae | Saccharomonospora/Saccharopolyspora | ||

| ActiD2 (1.108) | 406 | 0 | 11 | Actinomycetaceae | Actinomyces | ||

| Frank16 (1.069)d | 492 | 20 | 247 | Frankiaceae | Frankia | ||

| Rik6 (1.148)d | 152 | 0 | 20 | Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidetes | Rikenellaceae | Rikenella |

| Lyng2 (1.104)d | 216 | 0 | 49 | Cyanobacteria | Cyanobacteria | Oscillatoriaceae | Lyngbya |

| Campy (1.154)d | 949 | 520 | 720 | Proteobacteria | Epsilonproteobacteria | Campylobacteraceae | Campylobacter |

| Cycle 3 (Comp1) | |||||||

| AcidUnc (0.869)e | 635 | 955 | 512 | Acidobacteria | Uncultured Acidobacteria (cluster 1) | ||

| Blatta1 (0.962)e | 198 | 2,418 | 407 | Bacteroidetes | Flavobacteria | Unclassfied Flavobacteria | Blattabacterium |

| Flavo2 (0.947)e | 505 | 3,724 | 949 | Flavobacteriaceae | Flavobacterium columnare | ||

| Ornit3 (0.809)d | 0 | 80 | 0 | Ornithobacterium | |||

| CFX109 (0.908) | 2,865 | 5,008 | 2,379 | Chloroflexi | Most Chloroflexi | ||

| Mogi12 (0.867)d | 182 | 654 | 0 | Firmicutes | Clostridia | Eubacteriaceae | Mogibacterium |

| Plancto4-mA (0.904)e | 2,786 | 4,290 | 2,297 | Planctomycetes | Most Planctomycetes | ||

| Brady6A (0.945)e | 572 | 1,582 | 298 | Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | Bradyrhizobiaceae | Bradyrhizobium, Afipia |

| Brady4 (0.862)e | 1,734 | 3,163 | 1,892 | Bradyrhizobiaceae | |||

| Xan (0.959)e | 433 | 2,823 | 613 | Hyphomicrobiaceae | Xanthobacter | ||

| Rhi (0.888)e | 781 | 1,530 | 855 | Rhizobiaceae | Rhizobiaceae (except Agrobacterium) | ||

| Rgal157 (0.853)e | 686 | 1,439 | 691 | Some Rhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Phyllobacterium, Methylobacterium, Acetobacter, Gluconacetobacter, Rhodospirillacae | |||

| Rhodobact1B (0.932)e | 1,153 | 3,184 | 1,495 | Rhodobacteraceae | Rhodobacteraceae | ||

| Rhodo2 (0.990)e | 0 | 793 | 0 | Rhodospirillaceae | Rhodospirillum | ||

| Sphingo5B (0.908)e | 0 | 868 | 40 | Sphingomonadaceae | Most Sphingomonadaceae | ||

| Aldef5 (0.958)e | 112 | 1,117 | 255 | Betaproteobacteria | Alcaligenaceae | Alcaligenes defragans | |

| Burcep (0.912)e | 0 | 1,345 | 21 | Burkholderiaceae | Burkholderia cepacia | ||

| Hypal2 (0.893)e | 73 | 425 | 56 | Comamonadaceae | Hydrogenophaga palleronii | ||

| Herb1 (0.857)e | 37 | 1,498 | 388 | Oxalobacteraceae | Herbaspirillum | ||

| Allo1 (0.951)e | 27 | 344 | 0 | Gammaproteobacteria | Chromatiaceae | Allochromatium | |

| PseuD (0.953)e | 0 | 599 | 0 | Pseudomonadaceae | Pseudomonas spp. | ||

| Pseu1 (0.838)d | 84 | 451 | 10 | Pseudomonas spp. | |||

| PseubC4-6 (0.889)e | 95 | 370 | 23 | Pseudomonas corrugata | |||

| Achro1 (0.805)d | 0 | 430 | 0 | Thiotrichaceae | Achromatium | ||

| Cystb3 (0.971)e | 105 | 1,616 | 185 | Deltaproteobacteria | Cystobacteraceae | Cystobacter | |

| Cystb1 (0.951)e | 0 | 915 | 11 | Cystobacter | |||

| Cystb8 (0.919)e | 0 | 592 | 0 | Cystobacter | |||

| Cystb6 (0.916)e | 0 | 716 | 0 | Cystobacter | |||

| Anmxb6 (0.951)e | 205 | 1,373 | 8 | Myxococcaceae | Anaeromyxobacter | ||

| Anmxb5 (0.924)e | 295 | 1,400 | 50 | Anaeromyxobacter | |||

| MyxCor12 (0.977)e | 0 | 496 | 0 | Myxococcus/Corallococcus | |||

| MyxCor1 (0.976)e | 238 | 1,302 | 279 | Myxococcus/Corallococcus | |||

| MyxCor11 (0.875)e | 118 | 740 | 181 | Myxococcus/Corallococcus | |||

| Wolin2 (0.807)e | 0 | 194 | 0 | Epsilonproteobacteria | Helicobacteraceae | Wolinella succinogenes | |

| Cycle 5 (Comp|1|+|2|) | |||||||

| Aci1 (1.326)e | 5 | 13 | 186 | Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | Acetobacteraceae | Acidiphilium |

| Methylo1 (1.162)e | 273 | 186 | 410 | Methylobacteriaceae | Methylobacterium | ||

| B6.603 (1.367)e | 68 | 0 | 629 | Rhizobiaceae | Agrobacterium sp., some Rhizobium, some Brevundimonas | ||

| Rzbc820 (1.284)e | 243 | 0 | 708 | Rhizobiaceae, Brucella, Bartonella | |||

| Rzbc1247 (1.267)e | 946 | 655 | 1,558 | Rhizobiaceae, Brucellaceae, Bartonella, Phyllobacteriaceae, Blastochloris, Azospirillum irakense, Azospirillum amazonense | |||

| B6.437 (1.266)e | 95 | 10 | 292 | Agrobacterium sp., most Rhizobium | |||

| AgroAT41 m (1.214)e | 0 | 0 | 222 | Agrobacterium (biovar 1, A. rubi) | |||

| Alca1b (1.361)e | 63 | 0 | 930 | Betaproteobacteria | Alcaligenaceae | Alcaligenaceae 1 | |

| Alca2 (1.294)e | 28 | 0 | 992 | Alcaligenaceae 2 | |||

| Achrom4 (1.222)e | 77 | 0 | 787 | Achromobacter cluster | |||

| Burkho4C (1.333)e | 0 | 0 | 348 | Burkholderiaceae | Burkholderia glathei, B. multivorans | ||

| Var1 (1.333)e | 0 | 20 | 592 | Comamonadaceae | Variovorax | ||

| Varpar (1.322)e | 212 | 62 | 1,265 | Variovorax paradoxus | |||

| Neiselon (1.320)e | 0 | 3 | 455 | Neisseriaceae | Neisseria elongata | ||

| XAN818 (1.205)e | 165 | 0 | 669 | Gammaproteobacteria | Xanthomonadaceae | Xanthomonadaceae | |

Probes having the highest correlations with between-group principal components (i.e., Comp|1|+2 for cycle 1 indicator probes, Comp1 for cycle 3, and Comp|1|+|2| for cycle 5; see Fig. 3) and being significant indicators in Indicator Species Analysis.

BGA gives values of principal components.

Microarray data were filtered and normalized; mean values from four replicate samples per vegetation cycle are shown.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

Probes PseubC2-10 and PseubC2BC3-2, targeting fluorescent pseudomonads from biocontrol clusters C3 to C5 (46), gave higher signals in cycles 3 and 5 than in the initial cycle (high correlations with the second axis, Fig. 3B). Pseudomonas strain TAD117 (GenBank accession number FJ225265), isolated in this study from G. graminis var. tritici-inoculated cycle 1 of the microcosm experiment, hybridized with the two probes. In addition, the 16S rRNA sequence of this isolate was closely related (99% identity) to Pseudomonas isolates (e.g., RX69) from TAD soils from western France (46).

DISCUSSION

The classical dogma in the case of monoculture-induced suppressiveness, derived from the analysis of TAD, is that two components are necessary for the development of suppressiveness. These are (i) monoculture of a susceptible host and (ii) the presence of a virulent pathogen leading to at least one strong disease outbreak (61). During TAD, major changes in the composition of the rhizobacterial community occur (48). However, the relative importance of both components as environmental factors determining rhizobacterial community composition has never been assessed, because typically it is difficult to separate their effects. Here, this issue was dealt with for the first time, thanks to an experimental design enabling us to separate the effects of monoculture and disease. In the G. graminis var. tritici-inoculated microcosms, a severe outbreak of the disease in the third vegetation cycle was followed by characteristic TAD (13) in the fourth cycle. Usually, this is attributed to the fact that the root lesions caused by serious G. graminis var. tritici infections increase the nutrient availability in the rhizosphere due to leakage from damaged tissue, leading to the selection of a specific rhizobacterial community with biocontrol activity (5, 12, 46). However, we observed very similar population shifts independent of either a take-all outbreak or TAD occurrence. In the noninoculated microcosms, G. graminis var. tritici was present in the soil as well, causing slight root blackening. Quantitative PCR (not shown) confirmed the presence of the pathogen in the soil, but this naturally present G. graminis var. tritici inoculum was not sufficient to cause severe take-all and TAD did not occur. These conditions were suitable to contrast the effects of monoculture versus disease in TAD-associated community changes.

Despite differences in disease severity (mainly monoculture cycle 3) and disease suppressiveness (monoculture cycle 5), the rhizobacterial communities in the inoculated and noninoculated systems did not differ significantly based on t-RFLP, regardless of the growth cycle. In contrast, significant changes between monoculture cycles were found, indicating that repeated barley cropping and not the disease outbreak combined with TAD succession was responsible for rhizobacterial community dynamics. This effect of barley monocropping was confirmed by 16S rRNA-based microarray analysis.

According to Garbeva et al. (18), the plant is the key element selecting certain microbial populations and having a strong influence on the development of suppressiveness. Consistent with this assumption, we detected the largest population shift from the first to the second vegetation cycle, both in the G. graminis var. tritici-inoculated soil and in the noninoculated soil. Probably, the reason for this shift is the initial cropping of the soil with spring barley, illustrating the adaptation of the microbial rhizosphere populations to a particular plant species. The continuation of barley monoculture leads to further refinement in this adaptation that could be detected as stepwise shifts in the population structure from cycle to cycle. This complies with a study by Smalla et al. (53) showing that plant-dependent shifts in the relative abundance of bacterial rhizosphere populations became more pronounced in the second year when a crop was grown for 2 consecutive years.

To identify bacterial taxa enriched in the course of barley monoculture, we compared the rhizobacterial communities from cycles 1, 3, and 5 with a taxonomic 16S rRNA microarray. A similar approach with the same microarray was recently reported by Kyselková et al. (27) for another plant disease (tobacco black root rot caused by Thielaviopsis basicola). As for G. graminis var. tritici, work on T. basicola so far has focused on antagonistic pseudomonads and the role of other rhizosphere bacteria has been neglected. To access these other rhizosphere populations, the authors applied the specifically developed microarray. Their results implicate an extension of the range of bacterial taxa hypothesized to participate in the suppression of black root rot, although they found other groups than we did for TAD. However, this emphasizes the specificity of soil suppressiveness for certain pathogens. Moreover, Kyselková et al. (27) reported that inoculation of the pathogen had no impact on rhizobacterial community composition, which is in accordance with our results.

In our study, the initial vegetation cycle was characterized by a high prevalence of actinomycetes (the whole Actinomycetales order, as well as several specific actinomycete genera). Actinomycetes are common in soil and the barley rhizosphere (64). Signal intensities for several cycle 1 indicators, such as Actinomycetales, Nocardioides, and Saccharopolyspora, decreased in cycle 3 and became high again in cycle 5. The latter trend might be important for TAD, as endophytic Actinobacteria (including Nocardioides) can prevent root colonization by G. graminis var. tritici (15) and actinomycete inoculation has been reported to reduce take-all disease severity (3).

The third vegetation cycle was characterized by the highest number of indicator taxa, which encompassed the phyla Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, and Planctomycetes. Probably, this reflects the fact that the rhizosphere of diseased plants typically is inhabited by larger bacterial populations due to the release of utilizable growth substrates from the infected tissues (39). Changes in the bacterial rhizosphere population in this stage often are due to secondary saprophytic colonizers, which need not necessarily affect biological control of G. graminis var. tritici. Similarly to previous studies of wheat TAD (48, 50), the Pseudomonas spp. increased significantly in the third cycle, but contrasting dynamics were found. While signals of probes targeting the genus Pseudomonas and the species Pseudomonas corrugata increased significantly in the third cycle and dropped in cycle 5, probes for fluorescent Pseudomonas from biocontrol clusters C3 to C5 (46) gave increased signals in the third cycle and remained at about the same level in the fifth cycle. Changes within Pseudomonas populations are known to be important for TAD development (12, 42, 49, 50).

The bioindicators for the last cycle belonged exclusively to Proteobacteria, which contrasts with the results of Sanguin et al. (48) for wheat TAD, where the latter stage was characterized by the most diverse bacterial community. Also, indicators at lower taxonomic levels often differed from those of Sanguin et al. (48), indicating that rhizobacterial community dynamics may be very dissimilar in different soils, crop species, and/or cultivation systems. Several of the cycle 5 indicator taxa are known to contain bacteria that stimulate plant growth, for example, Methylobacterium (31) and Achromobacter (24). Variovorax, residing on the rhizoplane or inside a plant, can promote plant growth via the reduction of ethylene levels and stimulation of root growth (7). This may be particularly relevant for biological control of G. graminis var. tritici, since replacement of diseased roots by new ones can restore normal plant growth in G. graminis var. tritici-tolerant barley (20). In addition, other indicator taxa, such as Agrobacterium (37), Rhizobium (52), and Burkholderia (51), include strains controlling soilborne fungal pathogens. Certain Burkholderia metabolites can suppress G. graminis var. tritici growth (21, 22, 57), and Burkholderia was one of the few bioindicators in common with the studies of Sanguin et al. (48) on wheat TAD and Kyselková et al. (27) on tobacco black root rot suppressiveness. However, it should be taken into account that these genera also harbor strains with no or adverse effects on plants and pathogens. Therefore, a functional analysis with representative strains of the identified taxa remains to be done in future work.

Certain plant species are able to enhance the proportion of antagonistic bacteria in the rhizosphere (e.g., see references 8, 14, 60, and 61), but here TAD did not lead to a significant difference in t-RFLP profiles. This suggests that TAD involved differences at lower taxonomic levels (e.g., within species) and/or in plant-beneficial gene expression in certain populations enriched during successive barley cropping. Similarly, Ramette et al. (44) hypothesized that suppressiveness to Thielaviopsis basicola may rely on the differential effects of environmental factors on the expression of key biocontrol genes in pseudomonads rather than differences in population structure of biocontrol Pseudomonas populations. Barret et al. (6) showed that mainly severe necrosis caused by G. graminis var. tritici altered the gene expression of biocontrol bacteria, whereas early G. graminis var. tritici colonization of roots and healthy roots had smaller or no effects. Therefore, it can be speculated that the microbial community shift we observed was caused by the plant whereas the biocontrol activity (which became manifest in a pronounced TAD in the soil inoculated with G. graminis var. tritici) originated in differential gene expression—caused by the pathogen, by plant components leaking from damaged root tissue, or by plant defense mechanisms—in the selected community. This needs to be targeted in future work.

In conclusion, barley monoculture had a strong impact on rhizobacterial community composition, while the effect of TAD itself was insignificant. Results suggest that TAD involved enrichment and/or gene expression phenomena within populations rather than changes between populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Haurat (UMR CNRS 5557 Ecologie Microbienne) for technical help and J. Esperschütz for mathematical support.

This work made use of the DTAMB technical platform at IFR 41 (Université Lyon 1).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, M. J. 2001. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Aust. Ecol. 26:32-46. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, M. J. 2005. PerMANOVA: a FORTRAN computer program for permutational multivariate analysis of variance. Department of Statistics, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand.

- 3.Andrade, O. A., D. E. Mathre, and D. C. Sands. 1994. Natural suppression of take-all disease of wheat in Montana soils. Plant Soil 164:9-18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asher, M. J. C., and P. J. Shipton. 1981. Biology and control of take-all. Academic Press, Inc., London, United Kingdom.

- 5.Barnett, S. J., I. Singleton, and M. Ryder. 1999. Spatial variation in populations of Pseudomonas corrugata 2140 and pseudomonads on take-all diseased and healthy root systems of wheat. Soil Biol. Biochem. 31:633-636. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barret, M., P. Frey-Klett, A.-Y. Guillerm-Erckelboudt, M. Boutin, G. Guernec, and A. Sarniguet. 2009. Effect of wheat roots infected with the pathogenic fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici on gene expression of the biocontrol bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf29Arp. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22:1611-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belimov, A. A., I. C. Dodd, N. Hontzeas, J. C. Theobald, V. I. Safronova, and W. J. Davies. 2009. Rhizosphere bacteria containing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase increase yield of plants grown in drying soil via both local and systemic hormone signalling. New Phytol. 181:413-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg, G., K. Opelt, C. Zachow, J. Lottmann, M. Gotz, R. Costa, and K. Smalla. 2006. The rhizosphere effect on bacteria antagonistic towards the pathogenic fungus Verticillium differs depending on plant species and site. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 56:250-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackwood, C. B., T. Marsh, S.-H. Kim, and E. A. Paul. 2003. Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism data analysis for quantitative comparison of microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:926-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borneman, J., and J. O. Becker. 2007. Identifying microorganisms involved in specific pathogen suppression in soil. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 45:153-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruce, K. D., W. D. Hiorns, J. L. Hobman, A. M. Osborn, P. Strike, and D. A. Ritchie. 1992. Amplification of DNA from native populations of soil bacteria by using the polymerase chain reaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3413-3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapon, A., A.-Y. Guillerm, L. Delalande, L. Lebreton, and A. Sarniguet. 2002. Dominant colonisation of wheat roots by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf29A and selection of the indigenous microflora in the presence of the take-all fungus. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 108:449-459. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook, R. 2003. Take-all of wheat. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 62:73-86. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook, R. J., L. S. Thomashow, D. M. Weller, D. Fujimoto, M. Mazzola, G. Bangera, and D. S. Kim. 1995. Molecular mechanisms of defense by rhizobacteria against root disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:4197-4201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coombs, J. T., P. P. Michelsen, and C. M. M. Franco. 2004. Evaluation of endophytic actinobacteria as antagonists of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici in wheat. Biol. Control 29:359-366. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culhane, A. C., G. Perriere, E. C. Considine, T. G. Cotter, and D. G. Higgins. 2002. Between-group analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 18:1600-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dufrêne, M., and P. Legendre. 1997. Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol. Monogr. 67:345-366. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garbeva, P., J. A. van Veen, and J. D. van Elsas. 2004. Microbial diversity in soil: selection of microbial populations by plant and soil type and implications for disease suppressiveness. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42:243-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffiths, R. I., A. S. Whiteley, A. G. O'Donnell, and M. J. Bailey. 2000. Rapid method for coextraction of DNA and RNA from natural environments for analysis of ribosomal DNA- and rRNA-based microbial community composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5488-5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutteridge, R. J., G. L. Bateman, and A. D. Todd. 2003. Variation in the effects of take-all disease on grain yield and quality of winter cereals in field experiments. Pest Manag. Sci. 59:215-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas, D., and G. Défago. 2005. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:307-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamdan, H., D. M. Weller, and L. S. Thomashow. 1991. Relative importance of fluorescent siderophores and other factors in biological control of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici by Pseudomonas fluorescens 2-79 and M4-80R. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:3270-3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornby, D. 1998. Take-all disease of cereals: a regional perspective. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 24.Jha, P., and A. Kumar. 2009. Characterization of novel plant growth promoting endophytic bacterium Achromobacter xylosoxidans from wheat plant. Microb. Ecol. 58:179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kabbage, M., and W. W. Bockus. 2002. Effect of placement of inoculum of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici on severity of take-all in winter wheat. Plant Dis. 86:298-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim, D.-S., R. J. Cook, and D. M. Weller. 1997. Bacillus sp. L324-92 for biological control of three root diseases of wheat grown with reduced tillage. Phytopathology 87:551-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyselková, M., J. Kopecký, M. Frapolli, G. Défago, M. Ságová-Marečková, G. L. Grundmann, and Y. Moënne-Loccoz. 2009. Comparison of rhizobacterial community composition in soil suppressive or conducive to tobacco black root rot disease. ISME J. 3:1127-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lebreton, L., P. Lucas, F. Dugas, A.-Y. Guillerm, A. Schoeny, and A. Sarniguet. 2004. Changes in population structure of the soilborne fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici during continuous wheat cropping. Environ. Microbiol. 6:1174-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Legendre, P., and E. D. Gallagher. 2001. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia 129:271-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lepš, J., and P. Šmilauer. 2003. Multivariate analysis of ecological data using CANOCO. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 31.Lidstrom, M. E., and L. Chistoserdova. 2002. Plants in the pink: cytokinin production by Methylobacterium. J. Bacteriol. 184:1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, W., T. Marsh, H. Cheng, and L. Forney. 1997. Characterization of microbial diversity by determining terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4516-4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manly, B. F. J. 1997. Randomization, bootstrap and Monte Carlo methodology in biology, vol. 70. Chapman & Hall/CRC, London, United Kingdom.

- 34.Marsh, T. L., P. Saxman, J. Cole, and J. Tiedje. 2000. Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis program, a web-based research tool for microbial community analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3616-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mavrodi, O. V., D. V. Mavrodi, L. S. Thomashow, and D. M. Weller. 2007. Quantification of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens strains in the plant rhizosphere by real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5531-5538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McArdle, B. H., and M. J. Anderson. 2001. Fitting multivariate models to community data: a comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology 82:290-297. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McClure, N. C., A.-R. Ahmadi, and B. G. Clare. 1998. Construction of a range of derivatives of the biological control strain Agrobacterium rhizogenes K84: a study of factors involved in biological control of crown gall disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3977-3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCune, B., J. B. Grace, and D. L. Urban. 2002. Analysis of ecological communities. MjM Software Design, Gleneden Beach, OR.

- 39.McSpadden Gardener, B. B., and D. M. Weller. 2001. Changes in populations of rhizosphere bacteria associated with take-all disease of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4414-4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mielke, H. 1998. Studien zum Befall des Weizens mit Gaeumannomyces graminis (Sacc.) von Arx et Olivier var. Walker unter Berücksichtigung der Sorten- und Artenanfälligkeit sowie der Bekämpfung des Erregers, vol. 359. Biologische Bundesanstalt für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Berlin, Germany.

- 41.Orphan, V. J., K. U. Hinrichs, W. Ussler III, C. K. Paull, L. T. Taylor, S. P. Sylva, J. M. Hayes, and E. F. DeLong. 2001. Comparative analysis of methane-oxidizing archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria in anoxic marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1922-1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raaijmakers, J. M., and D. M. Weller. 1998. Natural plant protection by 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas spp. in take-all decline soils. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 11:144-152. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramette, A. 2007. Multivariate analyses in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 62:142-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramette, A., Y. Moenne-Loccoz, and G. Defago. 2006. Genetic diversity and biocontrol potential of fluorescent pseudomonads producing phloroglucinols and hydrogen cyanide from Swiss soils naturally suppressive or conducive to Thielaviopsis basicola-mediated black root rot of tobacco. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 55:369-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryder, M. H., Z. Yan, T. E. Terrace, A. D. Rovira, W. Tang, and R. L. Correll. 1999. Use of strains of Bacillus isolated in China to suppress take-all and rhizoctonia root rot, and promote seedling growth of glasshouse-grown wheat in Australian soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 31:19-29. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanguin, H., L. Kroneisen, K. Gazengel, M. Kyselková, B. Remenant, C. Prigent-Combaret, G. L. Grundmann, A. Sarniguet, and Y. Moënne-Loccoz. 2008. Development of a 16S rRNA microarray approach for the monitoring of rhizosphere Pseudomonas populations associated with the decline of take-all disease of wheat. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40:1028-1039. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanguin, H., B. Remenant, A. Dechesne, J. Thioulouse, T. M. Vogel, X. Nesme, Y. Moënne-Loccoz, and G. L. Grundmann. 2006. Potential of a 16S rRNA-based taxonomic microarray for analyzing the rhizosphere effects of maize on Agrobacterium spp. and bacterial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4302-4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanguin, H., A. Sarniguet, K. Gazengel, Y. Moënne-Loccoz, and G. L. Grundmann. 2009. Rhizosphere bacterial communities associated with disease suppressiveness stages of take-all decline in wheat monoculture. New Phytol. 184:694-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarniguet, A., and P. Lucas. 1992. Evaluation of populations of fluorescent pseudomonads related to decline of take-all patch on turfgrass. Plant Soil 145:11-15. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarniguet, A., P. Lucas, and M. Lucas. 1992. Relationships between take-all, soil conduciveness to the disease, populations of fluorescent pseudomonads and nitrogen fertilizers. Plant Soil 145:17-27. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt, S., J. F. Blom, J. Pernthaler, G. Berg, A. Baldwin, E. Mahenthiralingam, and L. Eberl. 2009. Production of the antifungal compound pyrrolnitrin is quorum sensing-regulated in members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Environ. Microbiol. 11:1422-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharif, T., S. Khalil, and S. Ahmad. 2003. Effect of Rhizobium sp. on growth of pathogenic fungi under in vitro conditions. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 6:1597-1599. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smalla, K., G. Wieland, A. Buchner, A. Zock, J. Parzy, S. Kaiser, N. Roskot, H. Heuer, and G. Berg. 2001. Bulk and rhizosphere soil bacterial communities studied by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis: plant-dependent enrichment and seasonal shifts revealed. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4742-4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stralis-Pavese, N., A. Sessitsch, A. Weilharter, T. Reichenauer, J. Riesing, J. Csontos, J. C. Murrell, and L. Bodrossy. 2004. Optimization of diagnostic microarray for application in analysing landfill methanotroph communities under different plant covers. Environ. Microbiol. 6:347-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.ter Braak, C. J. F., and P. Šmilauer. 2002. CANOCO reference manual and CanoDraw for Windows user's guide: software for canonical community ordination (version 4.5). Microcomputer Power, Ithaca, NY.

- 56.Thioulouse, J., D. Chessel, S. Dolédec, and J.-M. Olivier. 1997. ADE-4: a multivariate analysis and graphical display software. Stat. Comput. 7:75-83. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomashow, L. S., and D. M. Weller. 1988. Role of a phenazine antibiotic from Pseudomonas fluorescens in biological control of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici. J. Bacteriol. 170:3499-3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tottman, D. R., and H. Broad. 1987. The decimal code for the growth stages of cereals, with illustrations. Ann. Appl. Biol. 110:441-454. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wawrik, B., L. Kerkhof, G. J. Zylstra, and J. J. Kukor. 2005. Identification of unique type II polyketide synthase genes in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2232-2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weisskopf, L., R.-C. Le Bayon, F. Kohler, V. Page, M. Jossi, J.-M. Gobat, E. Martinoia, and M. Aragno. 2008. Spatio-temporal dynamics of bacterial communities associated with two plant species differing in organic acid secretion: a one-year microcosm study on lupin and wheat. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40:1772-1780. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weller, D., J. Raaijmakers, B. McSpadden Gardener, and L. Thomashow. 2002. Microbial populations responsible for specific soil suppressiveness to plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40:309-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weller, D. M. 2007. Pseudomonas biocontrol agents of soilborne pathogens: looking back over 30 years. Phytopathology 97:250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weller, D. M., B. B. Landa, O. V. Mavrodi, K. L. Schroeder, L. De La Fuente, S. B. Bankhead, R. A. Molar, R. F. Bonsall, D. V. Mavrodi, and L. S. Thomashow. 2007. Role of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. in the defense of plant roots. Plant Biol. 9:4-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang, C. H., and D. E. Crowley. 2000. Rhizosphere microbial community structure in relation to root location and plant iron nutritional status. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:345-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]