Abstract

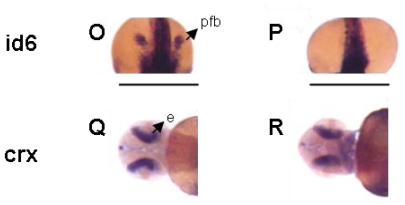

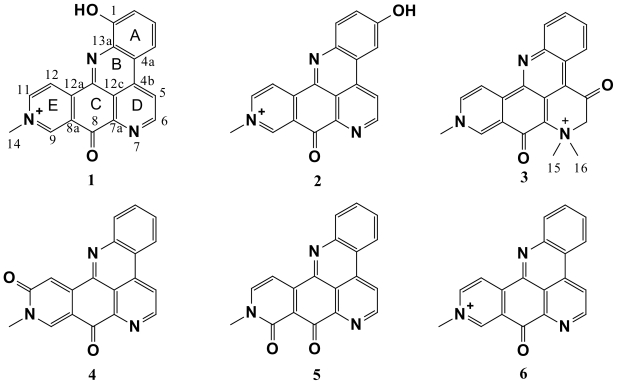

Three new minor components, the pyridoacridine alkaloids 1-hydroxy-deoxyamphimedine (1), 3-hydroxy-deoxyamphimedine (2), debromopetrosamine (3), and three known compounds, amphimedine (4), neoamphimedine (5) and deoxyamphimedine (6), have been isolated from the sponge Xestospongia cf. carbonaria, collected in Palau. Structures were assigned on the basis of extensive 1D and 2D NMR studies as well as analysis by HRESIMS. Compounds 1–6 were evaluated in a zebrafish phenotype-based assay. Amphimedine (4) was the only compound that caused a phenotype in zebrafish embryos at 30 μM. No phenotype other than death was observed for compounds 1–3, 5, 6.

Keywords: pyridoacridine alkaloids, Xestospongia cf. carbonaria, zebrafish

1. Introduction

Zebrafish have been identified as a valuable whole animal platform for phenotypic screening at various stages of the drug discovery process [1–4]. Some of the advantages that zebrafish offer in laboratory assays include the transparency of their embryos, allowing direct observation of organ morphology during treatment or visualization of specific molecular species using hybridization techniques; rapid development and short reproductive cycles; and easy maintenance in 96-well plates. Although the potential value of zebrafish in screening natural product extract libraries has been noted [5,6 ], to date relatively few zebrafish-based natural product screening programs, from either plants or marine sources, have been reported [7–9]. As part of a pilot study, we screened a prefractionated extract library [10] from marine invertebrates for zebrafish phenotypic activity. This small library included four fractions from each of forty organisms that were selected based on a known high incidence of cytotoxic compounds in their extracts. The rationale behind organism selection was to determine if our fractionation method is effective at enabling observation of phenotypic activity in the presence of strong background cytotoxicity. Within the 160 fractions, 25% exhibited embryo toxicity whereas an additional 8% caused various other phenotypic responses 24 hours after treatment. We report here the results from one of the organisms displaying activity, the sponge Xestospongia cf. carbonaria collected in Palau, which caused a phenotype of abnormal notochord development and death in the primary screen. Three new pyridoacridine alkaloids 1–3 as well as the known compounds 4–6, were isolated from a large scale extraction of this sponge. The pure compounds 1–6 were evaluated in the zebrafish assay, identifying amphimedine (4) as the agent responsible for the phenotypic response in the primary screen.

2. Results and Discussion

The specimen of Xestospongia cf. carbonaria was extracted with MeOH. The crude extract was separated on HP20SS resin according to a prefractionation protocol previously reported by this lab [11]. Subsequent bioassay-guided fractionation resulted in the isolation of the pyridoacridine alkaloids 1–3 as their respective trifluoroacetate salts, along with the known compounds amphimedine (4), neoamphimedine (5), and deoxyamphimedine (6). 1-Hydroxy-deoxyamphimedine (1) was obtained as a red-orange amorphous solid. A molecular ion in the positive HRESIMS spectrum at m/z 314.0945 corresponded to a molecular formula of C19H12N3O2 (Δ 4.8 ppm), which was isomeric with amphimedine (4) and neoamphimedine (5). The strong absorption bands at 3382 and 1687 cm−1 in the IR spectrum indicated that 1 contained a hydroxyl group and a conjugated carbonyl group. The structure of 1 was elucidated by interpretation of NMR data (Table 1) and comparison with spectral data for deoxyamphimedine (6). The only difference observed in the NMR data between 1 and 6 was in the A ring system. For 1, two doublets and one doublet of doublets at δH 7.48 (J = 8.0 Hz), 8.45 (J = 8.0 Hz) and 7.91 (J = 8.0, 8.0 Hz) ppm, respectively, indicated an additional hydroxyl present at either C-1 or C-4. The position of the hydroxyl group was identified as C-1 based on a NOESY correlation between signals at δH 8.45 (H-4) and 9.13 (H-5) ppm. The gHMBC spectrum also supported the assignment of 1 as 1-hydroxy-deoxyamphimedine.

Table 1.

1H and 13C-NMR data of pyridoacridine alkaloids (1–3).

| Posn. | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH, mult (JH-H) | δC, mult a | δH, mult (JH-H) | δC, mult b | δH, mult (JH-H) | δC, mult c | ||||

| 1 | 156.1 | C | 8.39, d (9.0) | 135.8 | CH | 8.19, d (9.0) | 143.0 | CH | |

| 2 | 7.48, d (8.0) | 116.5 | CH | 7.63, dd (9.0, 2.5) | 124.3 | CH | 7.73, dd (9.0, 7.5) | 128.4 | CH |

| 3 | 7.91, dd (8.0, 8.0) | 133.3 | CH | 162.7 | C | 7.84, dd (8.0, 7.5) | 133.5 | CH | |

| 4 | 8.45, d (8.0) | 114.5 | CH | 8.20, d (2.5) | 108.0 | CH | 9.27, d (8.0) | 125.1 | CH |

| 4a | 123.8 | C | 126.6 | C | 125.2 | C | |||

| 4b | 137.9 | C | 140.9 | C | 115.8 | C | |||

| 5 | 9.13, d (6.0) | 121.8 | CH | 9.00, d (6.0) | 122.9 | CH | 187.2 | C | |

| 6 | 9.37, d (6.0) | 150.2 | CH | 9.30, d (6.0) | 151.4 | CH | 4.41, s | 71.4 | CH2 |

| 7a | 147.0 | C | 149.5 | C | 115.1 | C | |||

| 8 | 180.0 | C | 180.6 | C | 161.0 | C | |||

| 8a | 130.3 | C | 130.8 | C | 132.7 | C | |||

| 9 | 9.87, s | 146.0 | CH | 9.82, s | 147.9 | CH | 9.72, s | 145.9 | CH |

| 11 | 9.40, d (6.5) | 147.8 | CH | 9.17, d (6.5) | 148.7 | CH | 8.75, d (6.5) | 142.0 | CH |

| 12 | 9.90, d (6.5) | 123.5 | CH | 9.38, d (6.5) | 124.1 | CH | 9.39, d (6.5) | 122.9 | CH |

| 12a | 147.9 | C | 149.2 | C | 143.5 | C | |||

| 12b | 143.1 | C | 145.5 | C | 139.5 | C | |||

| 12c | 120.1 | C | 120.8 | C | 129.9 | C | |||

| 13a | 134.4 | C | 141.5 | C | 143.1 | C | |||

| 14 | 4.57, s | 48.3 | CH3 | 4.58, s | 49.3 | CH3 | 4.53 | 49.0 | CH3 |

| 15 | 3.84, s (3H) | 54.1 | CH3 | ||||||

| 16 | 3.84, s (3H) | 54.1 | CH3 | ||||||

13C NMR data assigned based on the HSQC and HMBC in DMSO-d6 (500 MHz).

13C NMR data assigned based on the HSQC and HMBC in CD3OD (600 MHz).

13C NMR data assigned based on the HSQC and HMBC in CD3CN (500 MHz).

A molecular formula of C19H12N3O2 for 3-hydroxy-deoxyamphimedine (2) was consistent with both the HRESIMS (m/z 314.0938, [M]+, Δ 2.5 ppm) and with proton and carbon counts in the respective NMR spectra. Compound 2 is isomeric with 1 and showed a very similar IR spectrum suggesting the presence of a hydroxyl group (νmax 3421 cm−1) and an iminoquinone (νmax 1685 cm−1). 1H chemical shifts and coupling patterns for the A ring were different from those of 1. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 contained a broad doublet at δH 8.20 ppm (H-4, J = 2.5 Hz) and a doublet of doublets at δH 7.63 ppm (H-2, J = 9.0, 2.5 Hz) indicating that the hydroxyl was at C-3. Thus, the A ring in 2 was identified as being a 1, 3, 4-trisubstituted benzene, which marks the difference between 1 and 2. A 1D NOESY experiment also showed a correlation between signals at δH 8.20 (H-4) and 9.00 ppm (H-5) in 2, thus confirming the identity of 2 as 3-hydroxy-deoxyamphimedine.

The structure of debromopetrosamine (3) appeared in a review on marine pyridoacridine alkaloids [12], but the compound has never been formally described. The alkaloid 3 was isolated as a purple-blue amorphous solid and determined to have a molecular formula of C21H18N3O2 by HRESIMS (m/z 344.1415, [M]+, Δ 4.6 ppm). A strong and broad absorption band at 1682 cm−1 in the IR spectrum suggested that 3 contained multiple conjugated ketones. The gHSQC spectrum and 1H NMR data indicated seven aromatic protons, two methylene protons (δH 4.41, H-6) and nine N-methyl protons (δH 4.53, Me-14 and δH 3.84, Me-15, 16). The 1H chemical shifts and coupling patterns of ring A in 3 were nearly identical with those of amphimedine (4) and neoamphimedine (5). Ortho-coupled proton resonances at δH 8.75 (H-11) and δH 9.39 (H-12), along with a low-field proton at δH 9.72 (H-9) indicated 3 contained the same E ring pattern as deoxyamphimedine (6) although the 1H and 13C chemical shifts of Me-14 showed it was not attached to a quaternary nitrogen. The degenerate N,N-dimethyl proton singlets at δH 3.84 showed gHMBC correlations to an N-methyl carbon at δC 54.1, an aromatic quaternary carbon at δC 115.1 (C-7a), the methylene carbon at δC 71.4 (C-6) and a weak long-range correlation to δC 187.2 (C-5). Additionally, the gHMBC spectrum showed correlations from methylene protons δH 4.41 (H-6) to the degenerate N-methyl carbons C-15 and C-16 (δC 54.1), a quaternary aromatic carbon at δC 115.8 (C-4b), as well as the carbonyl at δC 187.2 (C-5). The gHMBC correlations between H-4 and C-4b; H-9 and C-8; H-11 and C12a; and H12 to C12b and C-8a elucidated the connectivities of the A, B, C, and D rings. COSY correlations from δH 9.72 (H-9) to δH 8.75 (H-11); from δH 9.27 (H-4) to δH 7.84 (H-3); from δH 8.19 (H-1) to δH 7.84 (H-3) and δH 7.73 (H-2); from δH 4.41 (H -6) to δH 3.84 (H -15, H-16); and from δH 8.75 (H-11) to δH 9.39 (H -12) and δH 4.53 (H -14) further confirmed the carbon connections. Based on these assignments and comparison of spectral data with those from the known compounds petrosamine [13] and petrosamine B [14], we conclude that 3 is debromopetrosamine.

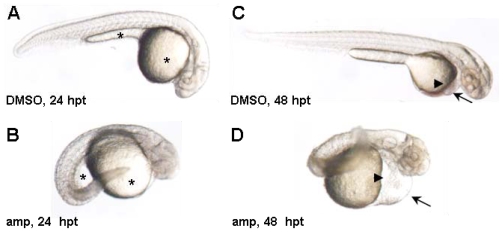

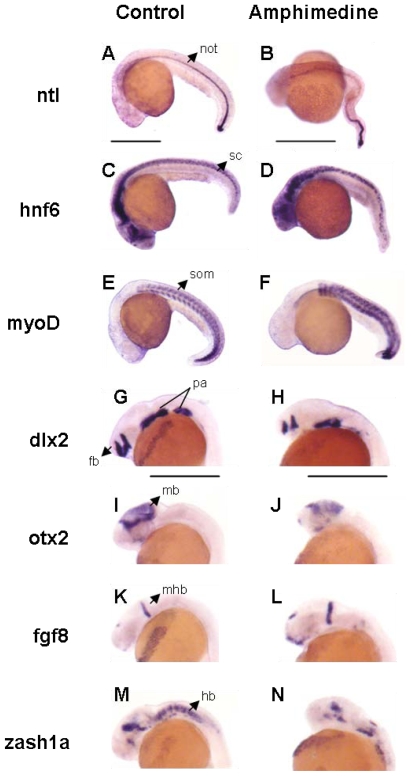

Of the pure compounds (1–6) isolated from this sponge, only amphimedine (4) showed a phenotype in the zebrafish assay at 30 μM. Embryos exposed to amphimedine (4) exhibited necrosis, pericardial edema and an enlarged yolk with thin extension (Figure 2B, D). The embryos also appeared short and grainy, with an extended heart, weak heartbeat, no circulation, and irregular curvature of the tail (Figure 2B, D). In order to further characterize the phenotypes induced by amphimedine (4), a series of in situ hybridization experiments were carried out that utilized digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes against various regulatory genes involved in development and differentiation. These studies enabled selective high-contrast imaging of various organs. Treated embryos showed wavy notochord, spinal cord and abnormally shaped somites after imaging of ntl, hnf6 and myoD, respectively (Figure 3B, D, F). They also lack pectoral fin buds, have slightly smaller eyes and shortened brain regions as shown by the imaging of known brain markers such as dlx2, otx2, fgf8 and zash1a (Figure 3H, J, L, N, P, R). The variety and severity of phenotypic responses induced by amphimedine (4) suggest interference with a fundamental process in embryonic development or action against multiple systems. Unfortunately, at this time it is not possible to infer from the pattern of activities observed which specific targets amphimedine (4) might be modulating.

Figure 2.

Amphimedine-treated embryos exhibit heart, yolk and body shape defects. Treatment of embryos seven hours post-fertilization (hpf) with 30 μM amphimedine (amp) resulted in pericardial edema (arrow), extended heart (arrow head), enlarged yolk with thin extension (*), curving of the body and general necrosis at 24 hours post-treatment (hpt; B) and 48 hpt (D) compared to the DMSO-treated controls (A and C, respectively).

Figure 3.

Additional developmental defects resulting from amphimedine treatment. In situ hybridization was performed on control (A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, Q) and treated (B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P, R) embryos harvested at 24 h (ntl, hnf6, myoD, dlx2, otx2, fgf8, zash1a, id6) or 48 h (crx) post treatment. Scale bars, 50 μM. not, notochord; sc, spinal cord; som, somites; pa, pharyngeal arches; fb, forebrain; mb, midbrain; mhb, mid/hindbrain boundary; hb, hindbrain; pfb, pectoral fin bud; e, eye.

Since the first pyridoacridine, amphimedine (4) was identified in 1983 [15], over a hundred pyridoacridine alkaloids have been isolated from marine sources [16]. The bioactivity most often reported for pyridoacridine molecules has been cytotoxicity [17–22], although a wide array of other biological activities have also been documented, such as antimicrobial [23,24], anti-viral [25], and DNA-directed activities [26]. Neoamphimedine (5), a known topoisomerase II inhibitor [17], was not active in the zebrafish screen, which is consistent with our observations that other known top2 inhibitors, including etoposide, daunorubicin and doxorubicin show no phenotype, illustrating both the selectivity of the assay and the remarkable versatility of the pyridoacridine family. From a structure activity viewpoint, it is clear that minor structural differences can have a marked effect on the biological activity of the pyridoacridine class of compounds. It is worth noting that amphimedine (4), despite its low abundance relative to the toxic pyridoacridines also present in the extract, displayed observable activity in fairly crude fractions. This suggests that modest fractionation schemes that can be carried out in parallel with many extracts at low cost can be sufficient to allow detection of compounds causing interesting phenotypes, even in the presence of cytotoxic compounds.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

UV spectra were acquired in spectroscopy grade MeOH using a Hewlett-Packard 8452A diode array spectrophotometer. IR spectra were recorded on a JASCO FT/IR-420 spectrometer. NMR data for compounds 1–3 were acquired using a Varian INOVA 500 (1H 500 MHz, 13C 125 MHz) NMR spectrometer with a 3mm Nalorac MDBG probe or Varian INOVA 600 (1H 600 MHz, 13C 150 MHz) NMR spectrometer with a 5 mm Cold Probe for compound 2 referenced to residual solvent (δH 2.49, δC 39.51 for DMSO-d6; δH 3.30, δC 49.15 for CD3OD; and δH 1.94, δC 118.69 for CD3CN). High-resolution ESIMS analyses were performed on a Micromass Q-tof micro. Initial purification was performed on HP20SS resin. HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1100 system using Luna Phenyl-Hexyl (Phenomenex, Inc.) (250 × 10 mm, 5 μm; 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) and Luna C18 (Phenomenex, Inc.)(250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) columns.

3.2. Biological Material

In order to obtain sufficient quantity of metabolites for biological testing, a large-scale collection of the source sponge was conducted. This sponge is identical to the material, Xestospongia cf. carbonaria, from which we previously reported the isolation of neoamphimedine [19]. This sponge is readily distinguished by its unique growth form, dark green staining pigmentation, and habitat. There has been confusion over its taxonomic placement, and it appears in the literature under several genus names including Amphimedon, Axinyssa, Neopetrosia, Pellina, and Xestospongia. Further investigation is needed to determine the correct taxonomic assignment of this sponge.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

The Xestospongia cf. carbonaria specimen (1.206 kg) was extracted with 100% MeOH (3 × 1.8 L) to yield 54.26 g of crude extract. The crude extract was adsorbed on a 450 × 75 mm column packed with 80 g HP20SS resin that was sequentially eluted with 2 L each of water (FW), 25% (F1), 50% (F2), 75% (F3), and 100% (F4) IPA in water followed by 100% MeOH (F5). Fraction F1 (1.06 g) was partitioned between CHCl3 (3 × 200 mL) and 70% MeOH (aq; 200 mL). The dried aqueous MeOH phase was further fractionated by HPLC phenyl-hexyl employing MeOH/aqueous TFA (0.1%) gradients resulting in the isolation of compound 1 (1.0 mg), 2 (0.8 mg), 3 (3.0 mg), and deoxyamphimedine (6, 10.1 mg). Purification of the HP20SS F2 fraction yielded amphimedine (4, 1.2 mg) and neoamphimedine (5, 5.1 mg). Compounds 4–6 were identified by comparison to known standards.

1-Hydroxy-deoxyamphimedine (1): Trifluoroacetate salt; red-orange amorphous solid; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 204 (4.51), 246 (4.35), 286 (sh, 4.16), 392 (3.92) nm; IR (film) νmax 3382, 2925, 2854, 1687, 1598, 1507, 1206, 1136, 801, 723 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z314.0945 [M] +(calcd for C 19H12N3O2, 314.0930).

3-Hydroxy-deoxyamphimedine (2): Trifluoroacetate salt; orange-yellow amorphous solid; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 206 (4.95), 244 (4.94), 394 (3.34), 488 (3.24) nm; IR (film) νmax 3421, 2925, 1685, 1505, 1443, 1210, 1139, 844, 803, 724 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z314.0938 [M] +(calcd for C 19H12N3O2, 314.0930).

Debromopetrosamine (3): Trifluoroacetate salt; purple-blue amorphous solid; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 216 (4.49), 282 (4.74), 374 (3.38), 592 (3.15) nm; IR (film) νmax 3063, 1682, 1648, 1588, 1498, 1206, 1129, 801, 722 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 344.1415 [M]+ (calcd for C21H18N3O2, 344.1399).

3.4. Zebrafish Screen

Danio rerio (zebrafish) were maintained as previously described [27]. Fertilized embryos were collected following natural spawnings in 2X PTU (1X E3 medium, 30.4 mg/L phenylthiouera). Embryos were periodically checked for death and developmental delay. At seven hours post-fertilization (hpf), embryos were arrayed in 96-well plates at 1 embryo/well. Pure compounds were then added to the desired concentration, with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as vehicle control. DMSO was kept at 0.5% of the total assay volume. Embryos were grown at 28.5 °C and examined visually with a dissecting microscope at 1, 2, 3 and 6 days post treatment. Early toxicity was noted by examining the embryos at 1, 5, and 17 hours post treatment. Embryos were photographed live. All experiments were repeated at least twice, in duplicate.

In situ hybridizations were performed as previously described using digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes for crx (cone rod homeobox), dlx2 (distal-less homeobox protein 2), fgf8 (fibroblast growth factor 8), hnf6 (hepatocyte nuclear factor-6), id6 (inhibitor of DNA-binding/differentiation 6), myoD (myogenic differentiation1), ntl (no tail), otx2 (orthodentical homeobox protein 2) and zash1a (zebrafish achaete/scute homologue 1a) [28]. Embryos were photographed with an Olympus SZX12 digital camera.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds 1–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank Carole Bewley for collection of the sponge, and the Republic of Palau and the National Cancer Institute for collection permits. Funding for the Varian INOVA 500 MHz and 600 MHz NMR spectrometer was provided through NSF grant DBI-0002806 and NIH grant RR06262 and RR14768. This research was supported by NIH grant CA36622.

References

- 1.Bowman TV, Zon LI. Swimming into the future of drug discovery: in vivo chemical screen in zebrafish. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:159–161. doi: 10.1021/cb100029t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakraborty C, Hsu CH, Wen ZH, Lin CS, Aqoramoorthy G. Zebrafish: a complete animal model for in vivo drug discovery and development. Curr. Drug Metab. 2009;10:116–124. doi: 10.2174/138920009787522197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman CK, White RM, Zon LI. Chemical genetic screening in the zebrafish embryo. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:1422–1432. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pichler FB, Laurenson S, Williams LC, Dodd A, Copp BR, Love DR. Chemical discovery and global gene expression analysis in zebrafish. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:879–883. doi: 10.1038/nbt852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandrekar N, Thakur NL. Significance of the zebrafish model in the discovery of bioactive molecules from nature. Biotechnol. Lett. 2009;31:171–179. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9868-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford AD, Esquerra CV, de Witte PA. Fishing for drugs from nature: zebrafish as a technology platform for natural product discovery. Planta Med. 2008;74:624–632. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He MF, Liu L, Ge W, Shaw PC, Liang R, Wu LW, But PPH. Antiangiogenic activity of Tripterygium wilfordii and its terpenoids. J. Ethnopharm. 2009;121:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suyama TL, Cao Z, Murray TF, Gerwick WH. Ichthyotoxic brominated diphenyl ethers from a mixed assemblage of a red alga and cyanobacterium: structure clarification and biological properties. Toxicon. 2010;55:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kita M, Roy MC, Siwu ER, Noma I, Takiguchi T, Itoh M, Yamada K, Koyama T, Iwashita T, Uemura D. Durinskiol A: a long carbon-chain polyol compound from the symbiotic dinoflagellate Durinskia sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:3423–3427. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bugni TS, Harper MK, McCulloch MW, Reppart J, Ireland CM. Fractionated marine invertebrate extract libraries for drug discovery. Molecules. 2008;13:1372–1383. doi: 10.3390/molecules13061372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugni TS, Richards B, Bhoite L, Cimbora D, Harper MK, Ireland CM. Marine natural product libraries for high-throughput screening and rapid drug discovery. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:1095–1098. doi: 10.1021/np800184g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molinski TF. Marine pyridoacridine alkaloids: structure, synthesis, and biological chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1825–1838. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molinski TF, Fahy E, Faulkner JD, Van Duyne GD, Clardy J. Petrosamine, a novel pigment from the marine sponge Petrosia sp. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:1341–1343. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll AR, Ngo AN, Quinn RJ, Redburn J, Hooper JNA. Petrosamine B, an inhibitor of the Helicobacter pylori enzyme aspartyl semialdehyde dehydrogenase from the Australian sponge Oceanapia sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:804–806. doi: 10.1021/np049595s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmitz FJ, Agarwal SK, Gunasekera SP, Schmidt PG, Shoolery JN. Amphimedine, new aromatic alkaloid from a pacific sponge, Amphimedon sp. Carbon connectivity determination from natural abundance 13C-13C coupling constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:4835–4836. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall KM, Barrows LR. Biological activities of pyridoacridines. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004;21:731–751. doi: 10.1039/b401662a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall KM, Matsumoto SS, Holden JA, Concepcion GP, Tasdemir D, Ireland CM, Barrows LR. The anti-neoplastic and novel topoisomerase II-mediated cytotoxicity of neoamphimedine, a marine pyridoacridine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;66:447–458. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tasdemir D, Marshall KM, Mangalindan GC, Concepcion GP, Barrows LR, Harper MK, Ireland CM. Deoxyamphimedine, a new pyridoacridine alkaloid from two tropical Xestospongia sponges. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:3246–3248. doi: 10.1021/jo010153k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Guzman FS, Carte B, Troupe N, Faulkner DJ, Harper MK, Concepcion GP, Mangalindan GC, Matsumoto SS, Barrows LR, Ireland CM. Neoamphimedine: a new pyridoacridine topoisomerase II inhibitor which catenates DNA. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:1400–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thale Z, Johnson T, Tenney K, Wenzel PJ, Lobkovsky E, Clardy J, Media J, Pietraszkiewicz H, Valeriote FA, Crews P. Structures and cytotoxic properties of sponge-derived bisannulated acridines. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:9384–9391. doi: 10.1021/jo026459o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsay BS, Barrows LR, Copp BR. Structural requirements for biological activity of the marine alkaloid ascididemin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995;5:739–742. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clement JA, Kitagaki J, Yang Y, Sauceds CJ, McMahon JB. Discovery of new pyridoacridine alkloids from Lissoclinum cf. badium that inhibit the ubiquitin ligase activity of Hdm2 and stabilize p53. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:10022–10028. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charylulu GA, McKee TC, Ireland CM. Diplamine, a cytotoxic polyaromatic alkaloid from the tunicate Diplosoma sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:4201–4202. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarthy PJ, Pitts TP, Gunawardana GP, Kelly-Borges M, Pomponi SA. Antifungal activity of meridine, a natural product from the marine sponge Corticium sp. J. Nat. Prod. 1992;55:1664–1668. doi: 10.1021/np50089a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luedtke NW, Hwang JS, Glazer EC, Gut D, Kol M, Tor Y. Eilatin Ru(II) complexes display anti-HIV activity and enantiomeric diversity in the binding of RNA. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:766–771. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020802)3:8<766::AID-CBIC766>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall KM, Holden JA, Koller A, Kashman Y, Copp BR, Barrows LR. AK37: the first pyridoacridine described capable of stabilizing the topoisomerase I cleavable complex. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2004;15:907–913. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200410000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westerfield M. A Guide for the Laboratory use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) 3rd ed. University of Oregon Press; Eugene, OR, USA: 1995. p. 385. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nauduld LD, Sandoval IT, Chidester S, Yost HJ, Jones DA. Adenomatous polyposis coli control of retinoic acid biosynthesis is critical for zebrafish intestinal development and differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:51581–51589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]