Abstract

The growing drug resistance of Plasmodia spp. to current antimalarial agents in the quinine and artemisinin families further asserts the need for novel drug classes to combat malaria infection. One approach to the discovery of new antimalarials is the screening of natural product extracts for activity against the formation of hemozoin, a biomineral essential to parasite survival. By mimicking the in vivo lipid-water interface at which native hemozoin is found, hemozoin can be synthesized outside the parasite. In this work, a variety of lipophilic mediators was used to determine the optimal platform for in vitro hemozoin formation and then tested for efficacy in preliminary screens containing crude natural product extracts. The complete optimization and validation of a NP-40 detergent-mediated assay provide a screening template with an expedited 4-hour incubation time and identical IC50 values to those measured from the parasite’s native lipid component.

Introduction

During malarial infection, the parasite catabolizes host hemoglobin to acquire amino acids therefore becoming exposed to the oxidative stress caused by liberated free heme [1]. In order to avoid heme toxicity, the parasite sequesters heme into aggregates of dimeric ferriprotoporphyrin IX (Fe(III)PPIX) called hemozoin (HZ). Throughout history, HZ has been reported in association with malaria [2] but was not structurally elucidated until the late 20th century [3]. These dimeric units aggregate via an extended network of hydrogen bonds between the propionate groups of the porphyrins. Native HZ and its synthetic analogue, β-hematin (BH), are crystallographically identical. The two structures are dimeric five-coordinate Fe(III)PPIXs with reciprocal monodentate carboxylate interactions [3]. While the structural makeup of HZ has been examined extensively [4–7], the crucial step of hemozoin formation in the parasite digestive food vacuole (DV) remains a mystery.

Over the years, several hypotheses have been proposed for the mechanism of HZ formation, including enzyme catalysis [8] or protein mediated formation [9], lipid mediated formation [10–12] and spontaneous formation [13] or autocatalysis [14]. Recently, the weight of evidence has swung strongly towards a lipid mediated process. Transmission electron microscopy of the trophozoite stage of Plasmodium falciparum infected red blood cells revealed nanosphere lipid droplets containing HZ crystals [15]. These droplets consist of a blend of fatty acyl glycerides (specifically monostearic, monopalmitic, dipalmitic, dioleic and dilinoleic glycerols). When extracted, they promoted the formation of BH both individually and as a blend [15]. BH crystallization may be favored in a hydrophobic environment in which hydrogen bonds between the hydrophilic Fe(III)PPIX’s propionate linkages are preferred [16, 17]. This beneficial solubility in a lipophilic setting was also shown to hold true when the common laboratory surfactants SDS, Tween 80 and Tween 20 were used to mediate BH crystallization [12, 18].

Conversion of these templates and subsequent reactions into a biologically relevant, yet robust, primary screen for compounds that inhibit the HZ pathway presents a challenge. Like many of its predecessors, the lipid-based assay must meet suitable performance criteria with regard to time, expense, resources and validation, which cumulatively dictate an assay’s success and future applicability [9, 13, 19–22]. For instance, the radioactive hematin polymerization assay developed by Kurosawa et al. requires trophozoite lysates, overnight incubation and is subject to the expense and restrictions imposed on any assay containing a radio-labeled substrate [20]. While the assay was used to screen over 100,000 compounds for BH inhibition [20], its practical use in other labs is limited to those with the training and resources to work with radioactive materials and Plasmodium cultures. Equally problematic, are assays incapable of quantifying the degree of BH crystallization [13] or assays that require starting materials not commercially available [9, 21].

By using the neutral lipid blend ratio found in trophozoite HZ extracts to mediate BH formation [15], most, if not all, labs should be capable of mimicking the acidic and lipid-rich environment of the parasite’s DV in vitro. The potential for further simplification of lipid-based assays was shown by Huy et al. with the use of the detergent Tween 20, curtailing not only the cost of the assay’s lipophilic template but also the incubation time of the assay to 4 h [18]. Both of these assays produced comparable amounts of BH under similar acidic and hydrophobic conditions. However, when used to generate concentration response curves of known BH inhibitor chloroquine, the drug IC50 values from the Tween 20 mediated assay were approximately 10-fold higher than those obtained with the neutral lipid blend [15, 18]. This significant difference suggests that Tween 20 is not the most accurate mimic of the native neutral lipid blend. Herein, a series of lipophilic templates were surveyed for use in BH crystallization assays. The robustness of the assays was then tested in the preliminary screening of a small library of natural product extracts (NPEs).

Materials and Methods

Hemin (≥98%, Fluka BioChemica), sodium acetate trihydrate, 1-stearoyl-rac-glycerol (MSG), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-rac-glycerol (DPG), 1,2-dioleoyl-rac-glycerol (DOG), 1,3-dilinoleoyl-rac-glycerol (DLG), 3-palmitoyl-sn-glycerol (MPG), chloroquine, amodiaquine, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), sodium hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate, tannic acid, chlorophyll a, ethylenediaminetetracetic acid (EDTA), ethyleneglycol-bis-N,N′-tetracetic acid (EGTA), DL-1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT), cysteine, glutathione, Tween 20, calcium carbonate, sodium iodide, copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate and ethyl acetate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), Triton X-100, Tween 80 and 3-(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) were obtained from Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL. Dextrose, soluble starch, beef extract, yeast extract, fish meal, tryptone, dimethyl sulfoxide, ammonium acetate, acetone, catechin, gallic acid, acetonitrile, and ethanol were bought from Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA. Molasses was purchased from Whole Foods, Austin, TX. Quinine bark (red cinchona) was purchased from TerraVita, Ontario, Canada.

Dehydrohalogenation BH Synthesis

BH was prepared following the Bohle dehydrohalogenation method [23]. The reaction was protected from light and allowed to stand for 3 months. The final product was filtered and washed exhaustively with methanol, 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate (pH 9.1) and deionized water. Once purified, the BH was dried 48 h at 150 °C under vacuum and stored under dessicant.

Neutral Lipid Initiated BH Crystallization Assay

Lipid mediated BH formation was adapted from previous description [15]. A 25 mM hematin stock solution was prepared by dissolving 16.3 mg of hemin in 1.0 mL DMSO and filtering through a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane syringe driven filter unit. From this 25 mM solution, 177.8 μL was added to 20 mL of a 0.2 M ammonium acetate solution, pH 4.9 for a final 222.2 μM hematin stock. Lipids (1-Stearoyl-rac-glycerol; 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-rac-glycerol; 1,2-Dioleoyl-rac-glycerol; 1,3-Dilinoleoyl-rac-glycerol; or 3-Palmitoyl-sn-glycerol) were dissolved at 200 μM each in ethanol prior to addition to the assay. Final concentrations of 100 μM hematin, 0.1 M acetate buffer, 50 μM lipid solution, and 0–3.5 mM antimalarial (chloroquine or amodiaquine) were incubated in clear, 96-well round bottom plates at 37 °C in a water bath and shaken at 55 rpm for 20 h.

Detergent Initiated BH Crystallization Assay

Detergent mediated BH formation was adapted from previous description [18]. A 25 mM hematin stock solution was prepared by dissolving 16.3 mg of hemin in 1.0 mL DMSO and filtering through a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane syringe driven filter unit. From this 25 mM solution, 177.8 μL was added to 20 mL of the 2.0 M sodium acetate solution, pH 4.9 for a final 222.2 μM hematin stock. Final concentrations of 100 μM hematin, 1.0 M acetate buffer, detergent (9.77 μM Tween 20, 30.55 μM NP-40, > 58.62 μM Triton X-100, 1.47 mM CHAPS, 0.29 mM SDS, or 14.88 μM Tween 80), and 0–3.5 mM antimalarial were incubated in clear, 96-well round bottom at 37 °C in a water bath and shaken at 55 rpm for 4 h.

Assay Analysis

Assays were removed from incubation and centrifuged at 1100 × g for 1 h at 25°C in a Beckman Coulter AllegraX 22R, S2096 rotor. The supernatant was discarded and 200 μL of 0.15 M sodium bicarbonate, 2 % (w/v) SDS was added to each well. Centrifugation was repeated, and the supernatant, containing unreacted heme substrate, was removed. A final addition of 200 μL 0.36 M sodium hydroxide, 2% (w/v) SDS was used to dissolve the BH produced. The absorbance of the plates’ contents was measured at 400 nm on a BioTek SynergyHT plate reader. A molar extinction coefficient of 1×10−5 M−1cm−1 was used to calculate the BH formed. Sigmoidal concentration response curves were generated using GraphPad Prism v5.0 (March 7, 2007) software.

Fermentation

Production cultures of the actinomycete strain Nonomuraea kuesteri were initiated by transfer of 3 mL of seed culture into a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 30 mL “ET” medium containing 60 g/L molasses, 20 g/L Difco soluble starch, 20 g/L fish meal, 0.1 g/L CuSO4·5H2O, 0.5 mg/L sodium iodide and 2 g/L calcium carbonate dissolved in distilled water, adjusted to a pH 7.2 before autoclaving. Fermentation of the production cultures was allowed to proceed at 30°C for 7 days in a shaker incubator.

Natural Product Extraction

An equal volume of ethyl acetate was added to the production culture, an emulsion was created by agitation and the solution was shaken for 1 h at 200 rpm. The extraction solution was transferred to a 50 mL Falcon tube and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 30 min in a Sorvall Legend RT, TTH-750 rotor. The ethyl acetate layer was collected, dried over MgSO4 and evaporated. Alternatively, an equal volume of methanol was added to the production culture and the solution was shaken for 1 h at 200 rpm. The extraction solution was transferred to a 50 mL Falcon tube and centrifuged at 3019 × g for 30 min as before. The methanol/water mixture was collected and evaporated. The resulting residue was dissolved in 1mL of methanol, 0.2 μm filtered and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS of Ethyl Acetate Extracts

Mass spectrometry was performed using ThermoFinnigan LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) concurrently in negative and positive ion modes. Nitrogen was used both for the auxiliary and sheath gas. The auxiliary and sheath gases were set to 20 psi and 36 psi, respectively. For positive ion mode, capillary temperature 300°C; source voltage 5.0 kV; source current 100 μA; capillary voltage 21.0 V; tube lens 45.0 V; skimmer offset 0.00 V; activation time 50 ms with an isolation width 1 m/z. For negative ion mode, capillary temperature 300°C; source voltage 4.5 kV; source current 100 μA; capillary voltage −49.0 V; tube lens −148.30 V; skimmer offset 0.00 V; activation time 50 ms with an isolation width 1 m/z. Data acquisition and quantitative spectral analysis were conducted using the Thermo-Finnigan Xcaliber software, version 2.0 Sur 1. Samples were introduced by a Waters Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA) with an injection volume of 10 μL. Secondary metabolites were separated on a Phenomenex Luna 5 μm C18 column (4.60 × 250mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) with a linear water-acetonitrile gradient (ranging from 95:5 to 5:95 water:acetonitrile) containing 10 mM ammonium acetate over 48 min with a flow rate of 1 mL/min split with 900 μL/min collected as fractions and 100 μL/min subjected to mass spectral analysis. Fractions were collected every minute in 96-well deep well plates using a Gilson FC204 fraction collector (Gilson, Middleton, WI). Each 96-well deep well plate was separated into 100 μL aliquots into 96-well plates, evaporated and subjected to assay conditions.

Results and Discussion

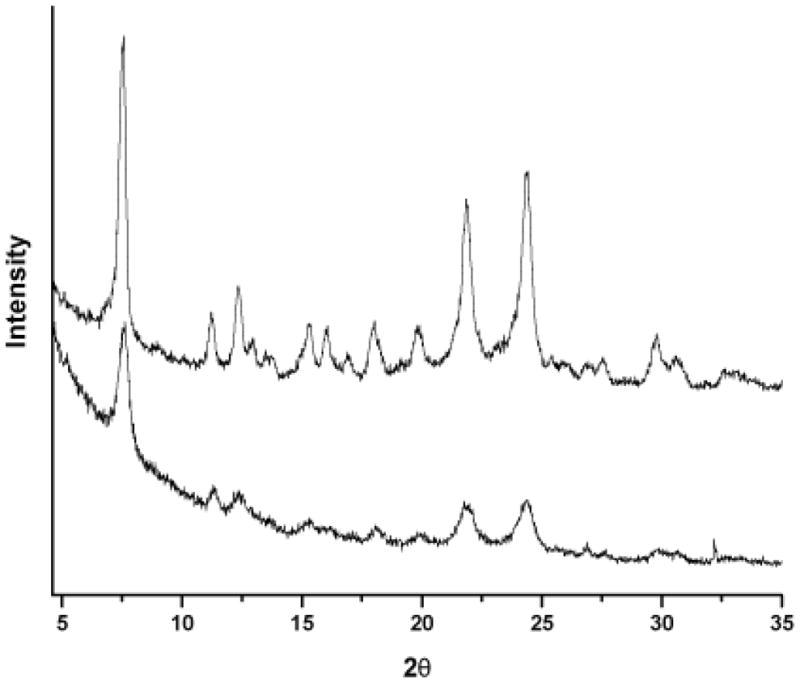

A series of lipophilic templates were evaluated for use in BH crystallization assays. The neutral lipid blend (a ratio of 4:2:1:1:1 monostearoyl-, monopalmitoyl-, dipalmitoyl-, dioleoyl-, and dilinoleoyl glycerols, respectively) used by Pisciotta et al., and the detergents studied by Shoemaker and Kamei represent biological and abiological controls [12, 15, 18]. A variety of detergents were selected, differing in chemical structure and ionic character. Initial detergent assay concentrations were estimated using a ratio of the detergent’s critical micelle concentration and the concentration of Tween 20 reported by Huy and coworkers [18]. The nonionic and non-denaturing detergents Triton X-100, NP-40, Tween 20 and Tween 80; the zwitterionic detergent, CHAPS; and an anionic, denaturing detergent, SDS, were examined for their ability to nucleate BH formation. The reaction products were evaluated by differential solubility, characteristic infrared spectroscopy stretches at 1664 cm−1 (C=O) and 1211 cm−1 (C-O) and powder x-ray diffraction (XRD). Comparison of the Bohle dehydrohalogenation BH product [23] and the NP-40 mediated BH product by XRD revealed a strong match to the representative 7°, 21° and 24° 2θ peaks, Fig. (1). The lipophilic mediators that were found to promote BH formation were evaluated in concentration response experiments with the antimalarials amodiaquine and chloroquine.

Figure 1.

Powder x-ray diffraction (Cu Kα radiation) of BH products. The XRD patterns of Bohle dehalogenation BH (top) and NP-40 mediated BH (bottom) were compared, and the characteristic 7°, 21° and 24° 2θ peaks were observed.

Of the six detergents surveyed, the zwitterionic CHAPS, nonionic Triton X-100 and anionic SDS were found to be inefficient mediators of BH crystallization; while the nonionic surfactants Tween 20, 80 and NP-40 effectively mediated the formation of BH with overall yields ≥69%, Table (1). Since HZ has been shown to aggregate in the presence of neutral lipid droplets in P. falciparum infected host red blood cells, the hydrophobic nature of the nonionic detergents is thought to effectively mimic the neutral lipid environment. This mimetic system allows the localization of high concentrations of heme, promoting dimer formation and aggregation.

Table 1.

Lipophilic Mediators of BH Formation.

| Lipophilic Mediator | Mediator (μM) | BH Produced (nmol) | Percent Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral Lipid Blend | 50 | 7.49 | 75 |

| NP-40 | 30.6 | 7.44 | 74 |

| Tween 20 | 9.77 | 7.11 | 71 |

| Tween 80 | 14.9 | 6.92 | 69 |

| SDS | 1140 | 1.01 | 10 |

| Triton X-100 | 58.6 | 0.74 | 7.4 |

| CHAPS | 1466 | 0.70 | 7.0 |

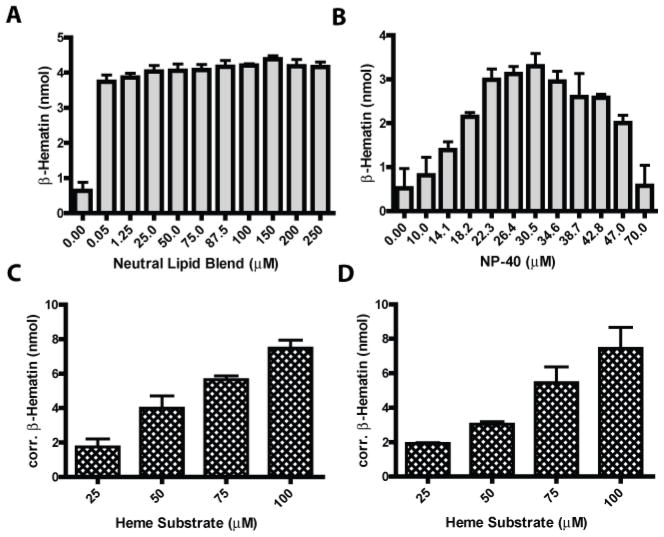

The adaptation of reaction parameters for optimal throughput and sensitivity was crucial in establishing assay viability for NP-40. The initial focus was directed at mediator concentration. A titration of neutral lipid and NP-40 was plotted against their respective BH yields, Fig. (2 A&B). For the neutral lipid blend, similar yields of BH were observed over a range of mediator concentrations from 50 nM to 50 μM, Fig. (2 A). These results illustrate the high efficiency of the native neutral lipid blend in mediating BH formation even at low nanomolar concentrations. In contrast, NP-40 demonstrated an optimal concentration for BH yields at 30.5 μM, Fig. (2 B). The reasons for the difference between the optimal template concentrations is unclear, but could be the result of a variation in the detergent’s ability to encompass substrate heme prior to the formation of propionate bonds in the hydrophilic reaction buffer.

Figure 2.

Assay optimization of substrate heme and lipophilic mediator. A) Lipid blend mediator concentrations were varied between 50 nM and 250 μM for optimal BH production. A specific concentration of neutral lipids was not observed. B) A titration of NP-40 was also carried out. Here, the optimal concentration of 30.5 μM showed the greatest yields of BH. C) Substrate heme was added increasingly to the neutral lipid blend assay in order to determine the optimal range (100 μM) without decreasing the assay’s S/N. D) Increasing amounts of heme were also added to the NP-40 assay, and as seen in the neutral lipid assay, were not shown to hinder assay S/N at ranges up to 100 μM heme.

Detergents have long been reported as mimics for native membrane lipids given their capability of binding hydrophobic surfaces in a micelle-like manner and facilitating ordered packing [24–28]. Using neutron diffraction methods, Roth et al. showed that fatty acid detergents promoted protein crystallization by exerting interactions that mediate effective molecular packing [29, 30]. By analogy, the detergent’s role in BH crystallization could be its ability to segregate free heme optimally along the lipid-water interface [15, 31]. As the fatty acyl glycerides used in the neutral lipid blend and NP-40 both contain hydrocarbon tails, it may simply be that the phenyl ring of the NP-40 changes the template packing enough that a more specific concentration of the detergent is required for optimal heme stacking and hence, BH assembly.

In order to optimize the assays’ BH yields, the optimal substrate heme concentration was determined. For these experiments, increasing concentrations of substrate heme were added to the reactions until a decline in signal to noise (S/N) was observed, Fig. (2C&D). When heme concentrations in the assay exceeded 100 μM, the signal to noise decreased by more than 70% (data not shown). Such a reduction is due to the increased and variable quantity of non-aggregated heme caught within the precipitate, while the yield of BH remains unchanged. Scaling the substrate from 50 μM to 100 μM, however, improved the BH yields approximately 60% with a S/N value of 14, an increase of 1.8 fold. The final optimized assay conditions employed 100 μM substrate heme and 30.5 μM NP-40 or 50 μM neutral lipid mediator.

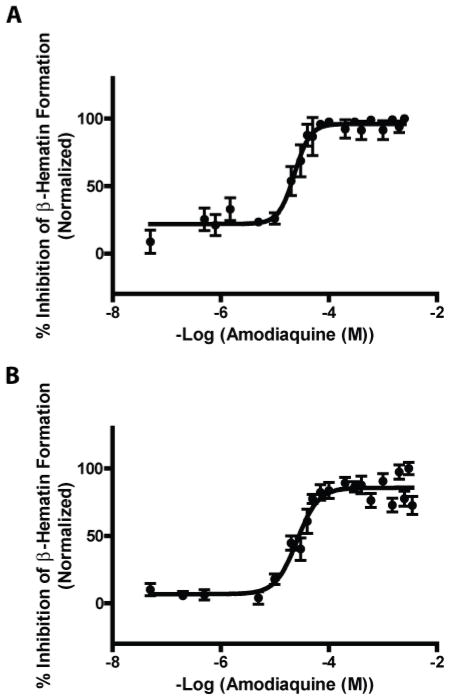

With optimized assay conditions, the efficacy of antimalarials known to inhibit BH crystallization was evaluated. Concentration response curves were generated for each of the lipophilic mediated assays in the presence of amodiaquine and chloroquine. The detergents Tween 20 and Tween 80 consistently exhibited 10-fold higher drug IC50 values than those for the DV neutral lipid blend, Table (2). In contrast, the NP-40 assay’s IC50 values closely resembled those of the neutral lipids’ and thus, provided an accurate yet inexpensive assay mimic for BH crystallization, Fig. (3 A&B). The similarity between the inhibition trends observed for the native lipid blend and NP-40 suggest that this surrogate would be capable of discerning other potential inhibitors of BH crystallization.

Table 2.

Efficacy of Known BH Inhibitors in the Lipophilic Mediated Assays.

| Lipophilic Mediator | Amodiaquine IC50 (μM) | Chloroquine IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral Lipid Blend | 23.07 | 85.26 |

| NP-40 | 25.73 | 50.99 |

| Tween 20 | 316.3 | 262.0 |

| Tween 80 | 201.8 | 195.7 |

| SDS | 225.4 | 245.6 |

| Triton X-100 | N/A | N/A |

| CHAPS | N/A | N/A |

Figure 3.

Amodiaquine concentration response curves of neutral lipid and NP-40 mediated BH formation assays. A) The IC50 value of amodiaquine in the neutral lipid mediated BH formation assay was 23.1 μM. B) The IC50 value of amodiaquine in the NP-40 mediated BH formation assay was 25.7 μM.

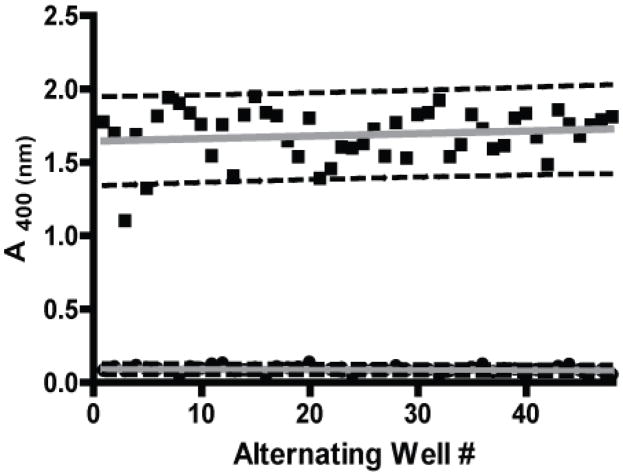

Assay performance and plate uniformity were validated to measure the general robustness of the method. Initial studies were conducted in 96-well plates with a checkerboard pattern of wells containing the acetate buffer vehicle and the positive controls of assay substrates with amodiaquine at its reported IC50 value, Fig. (4). The drift responses calculated from both lipid blend- and NP-40-mediated sample signals were less than 12%, well under the generally accepted 20% threshold. Negligible drift and edge effects were confirmed using linear regressions of the vehicle and positive control data with slopes of less than 2.5 × 10−3 illustrating the minimal shift in data across the plate. These findings reinforced that compound response could be screened with equal significance across each assay plate.

Figure 4.

Assessment of plate uniformity. Reaction plates were ran with a checkerboard pattern of alternating wells of acetate buffer (negative control) and the assay substrates heme-acetate buffer, NP-40 and IC50 25.7 μM amodiaquine (positive control). When plotted, the assay signal did not fluctuate along the edges of the plate nor across the plate, as confirmed by slopes of linear regression below 2.5×10−3 and low drift calculations of 12%.

In these multi-variable systems, there are often more contributing factors in an actual screen than accounted for by substrates alone. Therefore, assay performance was evaluated in the presence of possible interfering agents, Table (3). A number of potential contaminants were considered that might arise while screening a simple small molecule drug library or a complex natural product extract. Organic solvents commonly used in extraction methods like methanol and ethyl acetate were found to be compatible at final assay concentrations of less than 5% (v/v). The separation solvent, acetonitrile, did not perturb assay S/N measurements or BH yields at levels below 20% (v/v). Dimethyl sulfoxide, a common drug delivery vehicle, did not hinder assay signal below a 10% (v/v) final concentration. Common tannins, thiols and chelating agents at low concentrations were observed to have little effect. Likewise, natural plant pigment chlorophyll a did not alter assay output when maintained at concentrations of less than 0.13 mM. Methanol and ethyl acetate extracts of various growth media were not expected to be present at percentages higher than 0.02% (w/v) and no interference was observed at these levels. Cumulatively, these controls provided a high level of confidence that future “hits” would not be the result of common interfering agents.

Table 3.

Evaluation of Common Interfering Agents.

| Potential Interfering Agents | Range Tested | Observed Interference (≥) |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents | (v/v) | |

| Methanol | 0–30% | 5.0% |

| Ethanol | 0–30% | 5.0% |

| Acetonitrile | 0–30% | 20% |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | 0–30% | 10% |

| Acetone | 0–50% | 40% |

| Ethyl Acetate | 0–30% | 5.0% |

| Butanol | 0–30% | 5.0% |

| Chelating Agents | ||

| EDTA | 0–15 mM | 15 mM |

| EGTA | 0–15 mM | 6.0 mM |

| Tannins | ||

| Catechin | 0–1.0 mM | 0.26 mM |

| Gallic Acid | 0–1.0 mM | 0.13 mM |

| Tannic Acid | 0–1.0 mM | 0.13 mM |

| Thiol groups | ||

| DTT | 0–1.0 mM | 0.13 mM |

| Cysteine | 0–1.0 mM | 0.97 mM |

| GSH | 0–1.0 mM | 0.26 mM |

| Pigments | ||

| Chlorophyll a | 0–1.0 mM | 0.13 mM |

| Media Extracts | (w/v) | |

| K26S with Ethyl Acetate | 0–0.3% | 0.15% |

| K26S with Methanol | 0–0.3% | 0.25% |

| ET with Ethyl Acetate | 0–0.3% | 0.05% |

| ET with Methanol | 0–0.3% | 0.10% |

This high degree of optimization is crucial when the assay target is suspected to encounter a number of bioactive compounds during a screen. Such is the case when identifying potential drugs from crude natural products. Between 1981–2002, 52% of all new chemical entities introduced into the pharmaceutical pipeline was derived from natural products [32]. Even prior to this time period, alkaloids from the Cinchona tree and peroxides from the Qinghao shrub gave rise to the vital antimalarials quinine and artemisinin, respectively [33]. Unfortunately, parasite drug resistance continues to diminish what is left of the quinine derivatives’ efficacy, and reports of resistance to artemisinin combination treatments have emerged [33]. Since these antimalarials are currently to the fore in combating the disease, the need for new effective drugs is paramount.

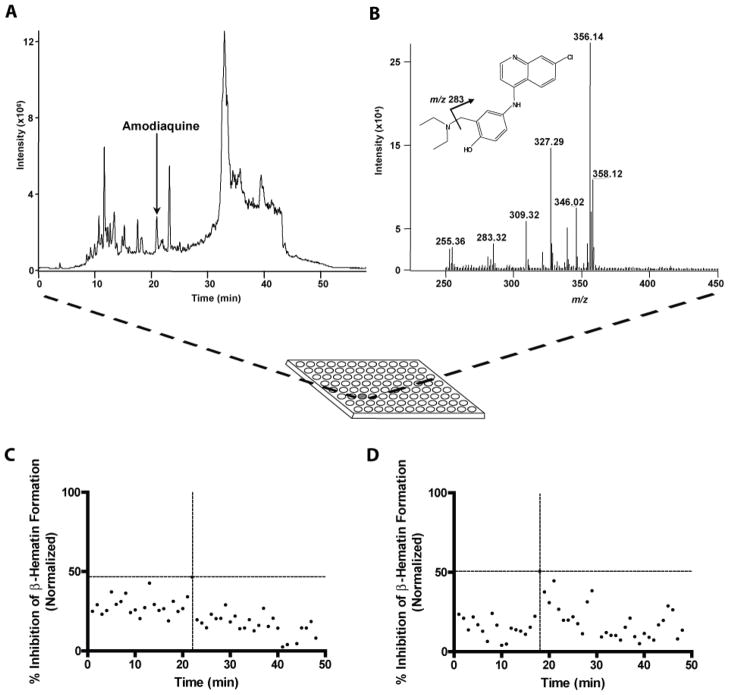

Given the importance of natural products as a source of effective antimalarials, the neutral lipid and NP-40 assays were subjected to trial screens of a small library of assembled natural product extracts (NPEs) from actinomycete and myxobacteria microorganisms [32, 34]. An extract of the cinchona tree, known to contain the BH inhibitor quinine, was also examined. These screens served as effective measures of the assays’ applicability under “real-world” conditions. To ensure the proper interpretation of the results, all extracts were spiked with the known antimalarial drug amodiaquine at its IC50. The NPEs were grown under various media conditions, extracted with either methanol or ethyl acetate, and all extracts were separated by an acetonitrile:water gradient using reverse phase liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometery (RP-LC-MS/MS). One milliliter fractions of each sample were collected per minute in 96-deep well source plates and transferred to 96-well destination plates for screening, ensuring synchronization with the LC-MS/MS data to facilitate spectral identification of each well’s compound(s). The amodiaquine (m/z 356 [M+H+]) was identified using MS/MS fragmentation and shown to elute at 21 min into well 22, Fig. (5 A&B). When the NPE plates were screened for activity, well 22 tested positive for approximately 50% BH inhibition, the predicted activity, Fig. (5C). The apparent activity of other metabolites in the assay are under investigation but may need to be further adapted in the assay with respect to an optimal concentration. Likewise, quinine (m/z 325 [M+H+]) from the ethanol extract of cinchona bark was identified with MS/MS fragmentation and shown to elute at 18 min into well 19, Fig. (5 D). The quinine obtained from this extraction retained activity with approximately 50% BH inhibition in the assay. These examples demonstrate the utility of the neutral lipid and NP-40 assays to selectively discriminate between bioactive hits, ultimately substantiating their potential use in future antimalarial drug screening.

Figure 5.

Natural product extracts in BH crystallization screens. A) Separation of amodiaquine from spiked K26S ethyl acetate natural product extracts. Amodiaquine eluted at 21 min into collection plate well number 22. B) Positive ion electrospray tandem mass spectrum of amodiaquine. Protonated amodiaquine was observed at m/z 356. A 37Cl isotopic ion was observed at m/z 358, and the characteristic MS/MS product ion from the 73 unit inductive cleavage of NH(C2H5)2 was detected at m/z 283. C) ET extracts in BH assay. Compounds collected from LC separation of ET natural product extracts were screened in the NP-40 mediated BH crystallization assay. The amodiaquine from the extract solution is indicated by the cross-hair dotted line. D) Cinchona bark extract in BH assay. Compounds collected from LC separation of the Cinchona bark extract were also screened with the NP-40 mediated BH crystallization assay. Quinine activity was observed in well 19 (18 min elutant) and is indicated by the cross-hair dotted line.

Conclusions

Despite almost universal resistance to chloroquine in Plasmodium falciparum, widespread mefloquine resistance and diminished efficacy of quinine, HZ remains a uniquely suitable target for antimalarial drugs. There is no compelling evidence for any change in HZ formation in resistant strains, and analogs of chloroquine retain activity against chloroquine resistant parasites [35–37]. However, the target pathway is complicated by the mystery of HZ’s in vivo formation. Evidence for a lipid-rich biomineralization template was most recently acquired in the extraction of HZ-surrounded neutral lipid droplets from P. falciparum infected red blood cells. These extracted neutral lipids were shown to act as an effective scaffold for in vitro BH formation [15]. Herein, two optimized lipid-based assays were shown to provide a robust assay platform for the discrimination of BH inhibitors against both common chemical interferants and the complex milieu of natural product extracts. In particular, the surfactant NP-40 is a newly used BH aggregation scaffold that requires less expensive materials than the specific blend of neutral lipids and expedites the processing time by 16 h. Validation studies and application in a preliminary screen of NPEs confirmed both the neutral lipid and NP-40 mediated assays’ potential in future high throughput drug screens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Defense grant W81XWH-07-ACA-0092 from the Army Medical Materiel Research Command and a National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 AI83145.

The authors also thank Dr. David L. Hachey and the staff of the Vanderbilt University Mass Spectrometry Research Center, Dagmara Derewacz for technical assistance and M.F. Richards for critical comments and editing of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Ziegler J, Linck R, Wright DW. Heme aggregation inhibitors: antimalarial drugs targeting an essential biomineralization process. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:171–189. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas LF. Neurological stamp. Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (1845–1922) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:520. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pagola S, Stephens PW, Bohle DS, Kosar AD, Madsen SK. The structure of malaria pigment beta-haematin. Nature. 2000;404:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35005132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitch C, Kanjananggulpan P. The state of ferriprotoporphyrin IX in malaria pigment. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:15552–15555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slater A, Swiggard W, Orton B, Flitter W, Goldberg D, Cerami A, Henderson G. An iron-carboxylate bond links the heme units of malaria pigment. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1991;88:325–329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohle D, Conklin B, Cox D, Madsen S, Paulson S, Stephens P, Yee G. Structural and spectroscopic studies of beta-hematin (the heme coordination polymer in malaria pigment) ACS Symp Ser. 1994;572:497–515. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohle D, Dinnebier R, Madsen S, Stephens P. Characterization of the products of the heme detoxification pathway in malarial late trophozoites by x-ray diffraction. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:713–716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slater A, Cerami A. Inhibition by chloroquine of a novel haem polymerase enzyme activity in malaria trophozoites. Nature. 1992;355:167–169. doi: 10.1038/355167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan DJ, Jr, Gluzman IY, Russell DG, Goldberg DE. On the molecular mechanism of chloroquine’s antimalarial action. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1996;93:11865–11870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bendrat K, Berger B, Cerami A. Haem polymerization in malaria. Nature. 1995;378:138–139. doi: 10.1038/378138a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorn A, Vippagunta S, Matile H, Bubendorf A, Vennerstrom J, Ridley R. A comparison and analysis of several ways to promote haematin (haem) polymerisation and an assessment of its initiation in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:737–747. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitch C, Cai GZ, Chen YF, Shoemaker JD. Involvement of lipids in ferriprotoporphyrin IX polymerization in malaria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1454:31–37. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(99)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan TJ, Ross DC, Adams PA. Quinoline anti-malarial drugs inhibit spontaneous formation of beta-haematin (malaria pigment) FEBS Lett. 1994;352:54–57. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00921-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorn A, Stoffel R, Matile H, Bubendorf A, Ridley R. Malarial haemozoin/beta-haematin supports haem polymerization in the absence of protein. Nature. 1995;374:269–271. doi: 10.1038/374269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pisciotta JM, Coppens I, Tripathi AK, Scholl PF, Shuman J, Bajad S, Shulaev V, Sullivan D., Jr The role of neutral lipid nanospheres in Plasmodium falciparum haem crystallization. Biochem J. 2007;402:197–204. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egan TJ, Chen JYJ, de Villiers KA, Mabotha TE, Naidoo KJ, Ncokazi KK, Langford SJ, McNaughton D, Pandiancherri S, Wood BR. Haemozoin (beta-haematin) biomineralization occurs by self-assembly near the lipid/water interface. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5105–5110. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huy NT, Maeda A, Uyen DT, Trang DTX, Sasai M, Shiono T, Oida T, Harada S, Kamei K. Alcohols induce beta-hematin formation via the dissociation of aggregated heme and reduction in interfacial tension of the solution. Acta Trop. 2007;101:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huy NT, Uyen DT, Maeda A, Trang DTX, Oida T, Harada S, Kamei K. Simple colorimetric inhibition assay of heme crystallization for high-throughput screening of antimalarial compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:350–353. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00985-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parapini S, Basilico N, Pasini E, Egan TJ, Olliaro P, Taramelli D, Monti D. Standardization of the physicochemical parameters to assess in vitro the beta-hematin inhibitory activity of antimalarial drugs. Exp Parasitol. 2000;96:249–256. doi: 10.1006/expr.2000.4583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurosawa Y, Dorn A, Kitsuji-Shirane M, Shimada H, Satoh T, Matile H, Hofheinz W, Masciadri R, Kansy M, Ridley RG. Hematin polymerization assay as a high-throughput screen for identification of new antimalarial pharmacophores. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2638–2644. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.10.2638-2644.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziegler J, Pasierb L, Cole KA, Wright DW. Metalloprophyrin probes for antimalarial drug action. J Inorg Biochem. 2003;96:478–486. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(03)00253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong CR, Sullivan DJ. Inhibition of heme crystal growth by antimalarials and other compounds: implications for drug discovery. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:2201–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohle DS, Helms JB. Synthesis of beta-hematin by dehydrohalogenation of hemin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193:504–508. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michel H, Oesterhelt D. Three-dimensional crystals of membrane proteins: bacteriorhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1980;77:1283–1285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garavito RM, Rosenbusch JP. Three-dimensional crystals of an integral membrane protein: an initial x-ray analysis. J Cell Biol. 1980;86:327–329. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel H. Three-dimensional crystals of a membrane protein complex. The photosynthetic reaction center from Rhodopseudomonas viridis. J Molec Biol. 1982;158:567–572. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michel H. Crystallization of membrane proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1983;8:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garavito RM, Markovic-Housley Z, Jenkins JA. The growth and characterization of membrane protein crystals. J Crystal Growth. 1986;76:701–709. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roth M, Lewit-Bentley A, Michel H, Deisenhofer J, Huber R, Osesterhelt D. Detergent structure in crystals of a bacterial photosynthetic reaction centre. Nature. 1989;340:659–662. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth M, Arnoux B, Ducruix A, Reiss-Husson F. Structure of the detergent phase and protein-detergent interactions in crystals of the wild-type (strain Y) Rhodobacter sphaeroides photochemical reaction center. Biochemistry. 1991;30:9403–9413. doi: 10.1021/bi00103a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barber J. Membrane proteins. Detergent ringing true as a model for membranes. Nature. 1989;340:601. doi: 10.1038/340601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chin YW, Balunas MJ, Chai HB, Kinghorn AD. Drug discovery from natural sources. AAPS J. 2006;8:E239–E253. doi: 10.1007/BF02854894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White NJ. Qinghaosu (artemisinin): the price of success. Science. 2008;320:330–334. doi: 10.1126/science.1155165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barton HA, Jurado V. What’s up down there? Microbial diversity in caves. Microbe. 2007;2:132–138. [Google Scholar]

- 35.De D, Krogstad FM, Cogswell FB, Krogstad DJ. Aminoquinolines that circumvent resistence in Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:579–583. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biot C, Glorian G, Maciejewski LA, Brocard JS. Synthesis and antimalarial activity in vitro and in vivo of a new ferrocene-chloroquine analogue. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3715–3718. doi: 10.1021/jm970401y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Neill PM, Mukhtar A, Stocks PA, Randle LE, Hindley S, Ward SA, Storr RC, Bickley JF, O’Neill IA, Maggs JL, Hughes RH, Winstanley PA, Bray PG, Park BK. Isoquine and related amodiaquine analogues: a new generation of improved 4-aminoquinoline antimalarials. J Med Chem. 2003;46:49333–4945. doi: 10.1021/jm030796n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]