Abstract

Background

Inadequate blood pressure (BP) control remains prevalent. One proposed explanation is “clinical inertia,” often defined as the failure by providers to initiate or intensify medication therapy when otherwise appropriate. However, patients could contribute to clinical inertia by signaling an unwillingness to consider medication intensification.

Objective

To explore covariates of patient attitudes regarding medication intensification.

Study Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

9 Midwestern U. S. Veterans’ Administration medical facilities.

Participants

1,062 diabetics identified as having BP>= 140/90 mm Hg as part of a prospective cohort study of clinical inertia in hypertension treatment.

Measurements

Primary outcome was participants’ indicated willingness to intensify BP medications if their provider noted elevated BP levels. Potential covariates assessed included BP control (actual and perceived), perceived importance of BP control, BP management self-efficacy, competing demands, medication factors (adherence and management issues), trust in provider, and sociodemographic factors.

Results

While 64% of participants reported complete willingness to intensify BP medications, 36% of participants expressed at least some unwillingness. In ordered logistic regression analysis, willingness to intensify was negatively associated with medication concerns, particularly concern about side effects (OR=0.49, 95% CI: 0.42, 0.59) and adherence or management problems (OR=0.72, 95% CI: 0.57, 0.91), and positively associated with perceived dependence of health on BP medications (OR=1.50, 95% CI: 1.26, 1.79) and trust in provider (OR=1.30, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.54). Importance of BP control had a weaker, non-significant association with willingness to intensify as well (OR=1.17, 95% CI: 0.99, 1.40). Neither competing demands, current BP control, current number of medications prescribed, nor self-efficacy was associated with willingness to intensify medications.

Conclusions

Patients’ willingness to consider intensification of BP medications appears primarily determined by how well patients are managing their current medications, rather than patients’ perceived importance of BP control, their self-efficacy, or their prioritization of BP control versus other health demands. Greater attention to patients’ pre-existing medication issues may improve providers’ ability to intensify BP medication therapy when medically appropriate while simultaneously improving patient satisfaction with care.

Keywords: patient acceptance of health care, patient compliance, treatment refusal, hypertension

Introduction

Inadequate blood pressure (BP) control has been well documented in a variety of clinical populations, especially among those with other conditions that magnify the risks of hypertension.[1-8] One particularly intriguing explanation for this fact is “clinical inertia,” often defined as the failure by providers to initiate or intensify medication therapy when otherwise appropriate.[9-12] Many factors may influence clinical inertia, including provider beliefs about when intensification of therapy is necessary, organizational limitations for follow-up of patient who present with elevated BP, and clinical uncertainty about what the patient's “true” BP is.[13]

However, patients could contribute to clinical inertia by influencing what is discussed in clinical consultations and consciously or unconsciously signaling an unwillingness to consider medication intensification. Patients' knowledge of hypertension risk has been shown to be limited,[14, 15] and lack of knowledge by patients of their target systolic blood pressure has been associated with worse blood pressure control.[16] Even when patients are knowledgeable, they may place less priority on treating hypertension if they also have other chronic health conditions,[17-19] pain, or other symptomatic concerns.[20] Physicians cite patients’ unwillingness as a reason for non-intensification,[21] but little research has examined the determinants of patient attitudes regarding medication intensification.

Increasing our understanding of such patient beliefs was one of the primary goals of the ABATe (Adressing BArriers to Translation) study, a comprehensive investigation into the provider, patient, and organizational factors underlying clinical inertia in the treatment of hypertension among veterans with diabetes.[13] To explore patient attitudes regarding medication intensification, the ABATe protocol included a detailed paper-and-pencil survey that directly asked patients how much of a problem they would have if their primary care provider recommended adding a new hypertension medication to their existing regimen. We then assessed to what degree measures of the patient factors discussed above were correlated with patients’ reported willingness to intensify.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a prospective cohort study of English-speaking diabetic patients who scheduled primary care visits at 9 Midwestern VA facilities. Working with 92 primary care providers, we identified a median of 14 diabetic patients per provider (range: 1-16) whose lowest visit triage systolic blood pressure was 140 mm Hg or greater or whose lowest triage diastolic blood pressure was 90 mm Hg or greater. (Visit triage policies specified that a second blood pressure measurement should be obtained if the first blood pressure was elevated.) A total of 1,556 patients were approached by staff, 213 were ineligible (mostly due to receiving primary diabetes care from a provider not participating in the study), and 1,169 patients were ultimately enrolled (87% of those approached and eligible). Participants received a $10 department store gift card as a thank you. See Kerr[13] for a more detailed description of the study population eligibility requirements and recruitment procedures.

Survey Design

At enrollment, patients were asked to complete a survey (detailed below) that assessed baseline characteristics and measures of adherence, prioritization, competing demands, self-efficacy, and other related issues. Questions were obtained from published sources and from a national pilot survey of 378 veterans with both diabetes mellitus and hypertension that assessed patient knowledge of BP targets and served as a test venue for new and adapted survey items.[22]

Variables

Outcome variable

Our primary outcome variable was a single question about patient willingness to intensify their medication regime that read as follows: “Imagine that your doctor told you that your blood pressure was a little high and that to lower it you should start taking a new blood pressure medication. How much of a problem would you have with adding a new blood pressure medication to the current medications you already take?” Study participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale, which was coded so that 1 meant “No Problem At All” and a response of 5 meant “A Very Large Problem.” We reverse transformed this variable so that higher numbers now indicate greater willingness to intensify.

Independent variables

BP Control

Our analyses include two objective measures of participants’ current BP control: the lowest systolic BP reading on the day of the visit and the average systolic BP over the prior year (each divided by 10 mm Hg to facilitate interpretation). Because self-perceptions of control may differ from actual control, we also asked participants to report how they would describe their BP “on average” on a 5-point scale of “lower than normal,” “normal,” “slightly high,” “high,” and “very high.”

Self-Efficacy re: BP control

Four questions assessed participants’ self-efficacy regarding managing their BP. Subjects used 5-point scales to rate (a) whether they understood what they need to do to manage their BP, (b) how confident they are in their ability to manage their BP, (c) how capable they believe they are at handling their BP, and (d) whether they felt able to meet the challenge of controlling their BP. The last three questions were adaptations of Williams’ Perceived Competence for Diabetes Scale for use in the BP context.[23] These questions were standardized (i.e., converted into the number of standard deviations above and below the variable mean) and then combined into a single scale with high reliability (alpha=0.85). The resulting standardized scale has a mean of 0, standard deviation of 1, and represents the underlying latent construct associated with our measures of patients’ BP-specific self-efficacy.

Importance of BP control

Participants answered three questions relating to their perceptions of the importance of intervening whenever blood pressure is elevated. Subjects used 4-point scales to indicate how concerning they felt blood pressure levels of 140/90 mm Hg and 165/95 mm Hg were, as well as whether or not they would expect a physician to intervene if a (hypothetical) diabetic patient had a BP of 140/90 mm Hg. These variables were then standardized and combined, with the resulting measure of perceived importance of BP control having an alpha of 0.64.

Competing Demands

We assessed competing demands from the patient's perspective in terms of four distinct categories: glycemic control, chronic pain, depression, and other issues.

Glycemic issues

Four questions (previously developed and tested in our pilot survey[22]) addressed how much glycemic issues may have overshadowed BP control issues in this diabetic population. First, respondents indicated whether they thought more about their BP or their blood sugars in their day-to-day life. A second question asked whether poor control of BP or blood sugars would be more likely to lead to a future heart attack. A third question posed a brief scenario of a diabetic patient with BP of 160/95 mm Hg and blood glucose levels in the 160-190 mg/dL range and asked which issue was more important to intervene on. Lastly, participants listed their top 3 health concerns out of a list of 10 (including a write-in “other” category). We took this ranking and created a variable to indicate whether participants ranked BP as above or below glycemic control or if neither was ranked in the top 3 concerns. These variables were all standardized and combined into a single scale with adequate reliability (alpha=0.54).

Pain

Because previous studies have shown that experiencing chronic pain for 6 months or longer often disrupts patients’ ability to perform self-management behaviors,[24, 25] we asked a single question to assess whether respondents had experienced pain that was present most of the time for 6 months or more during the past year.

Depression

We measured participant depression using Corson's PHQ-2 measure.[26] Participants rated how often they had (a) shown little interest or pleasure in doing things or (b) felt down, depressed, or hopeless in the last two weeks. Responses were standardized and combined into a single, highly reliable measure (alpha=0.85).

Other Issues

We also asked a global question to capture whether patients had other competing demands not captured above. Participants rated their agreement or disagreement with the statement “I have more pressing issues in my life than my health” using a 5 point scale.

Medication Issues

We asked four different types of questions to address participants’ medication adherence, management, and other concerns about their medications. Because such medication-related attitudes and behaviors may be related to the intensity of participants’ prescription medication regimes, our analyses also include an objective measure of how many different medications participants were prescribed as of the survey.

Number of Medications Prescribed

From automated data, we identified the total number of medication classes the patient was prescribed at any point in the 90 days prior to the enrollment visit (excluding as needed, topical, and short-term medications such as antibiotics, antifungals, and NSAIDs).

Concern about Side Effects

We asked two questions regarding medication side effects. Participants first indicated their level of agreement (on a 5-point “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” scale) with the statement “I sometimes worry about side effects of my blood pressure medicine(s),” which was adapted from Horne.[27] They then rated their overall level of concern about the side effects and risks caused by medications on a 5 point scale, where 1 meant “not at all concerned” and 5 meant “extremely concerned.” Responses were standardized and combined into a single scale with a reliability alpha=0.60.

Adherence/Management

We asked five questions about medication adherence and management. Participants completed Horne's 4 question Reported Adherence to Medication scale,[27] which includes two questions about forgetting to take medications and two about altering or missing doses to suit the patients’ needs. In addition, participants rated (on a 5 point scale) how difficult they felt it was to manage their current medications. Responses were standardized and aggregated into a single scale with a reliability alpha of 0.74.

Self-Restriction Due To Cost

Participants also answered one yes/no question about medication self-restriction due to cost: “In the past 12 months, have you ever taken less of any medications prescribed by your doctor because of the cost?”[28]

Perceived Dependence on BP Medications

We asked two questions, adapted from Horne's Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire,[27] to determine how much patients perceived themselves as dependent on their BP medications. Participants used a 5-point scale to rate their degree of agreement with the following statements: “Without my blood pressure medicine(s), I would be very ill” and “My health in the future will depend on my blood pressure medicine(s).” Responses were standardized and combined into a single measure with high reliability (alpha=0.70).

Trust in Provider

To assess patients’ trust in their health care providers, we asked three questions drawn from the trust subscale of the Primary Care Assessment Survey.[29] Participants rated their agreement with the statements “I completely trust my doctor's judgments about my medical care” and “My doctor cares more about holding down costs than about doing what is needed for my health” on 5-point scales and rated their overall trust in their doctor on a 0-10 scale. These measures were standardized and combined into a single scale with good reliability (alpha=0.71).

Covariates

We also included the following demographics variables in our primary analyses: respondent age, marital/partner status, education (3 categories), annual income (3 categories), and whether the respondent reported being any non-Caucasian race or ethnicity (supplemented by VA administrative data when the patient did not answer that question).

Analysis

We used ordered logistic regression to examine associations between the independent variables and participants’ ratings of their willingness to add a new medication to their current regime. All analyses were performed using Stata 10.[30]

While all regression variables had ≤10% missing cases (most ≤5%), the collective effect reduced the number of cases available for analysis from 1,062 to 771. To compensate, we used Royston's ice command, which implements the MICE (multiple imputation by chained equations) method of imputing missing values in the dataset for Stata.[31] We created 5 replicates of the dataset with missing values imputed, using linear regressions for continuous variables, ordered logistic regressions for 5-point Likert scale variables, and logistic regression for binary variables. We then used the micombine command to calculate the average regression estimates over the set of replicates, adjusting standard errors according to Rubin's rule. Such imputation techniques are recommended when missing data is a small fraction of the total data matrix yet is resulting in the removal of significant numbers of cases from the primary analysis. Results from analyses of the original, reduced dataset (omitted here for brevity) were consistently qualitatively similar to those obtained from the imputed dataset.

Calculation of predicted ordered logistic probabilities were done using Long and Freese's spost and prvalue commands.[32]

Results

Overall, 1062 of 1169 VA patients (91%) completed the survey instrument. Mean age was 65, but the age range included both participants in their 30s and in their 80s. One-quarter of participants described their racial / ethnic background in terms other than Caucasian (non-Hispanic), and all but 30 were male. Approximately 62% were married or with a partner, 46% had education beyond a high school diploma or GED, and only 10% reported an annual income of greater than $40,000 per year. Mean systolic BP at the focal visit was 147 mm Hg (range: 92-201), while the average prior year systolic BP was 145 mm Hg (range: 98-206). The mean number of non-short-term prescription medications taken within the preceding 90 days was 6.1 (range: 0-18), including a mean of 2.2 (range: 0-7) classes of hypertension medications (excluding furosemide and bumetanide).

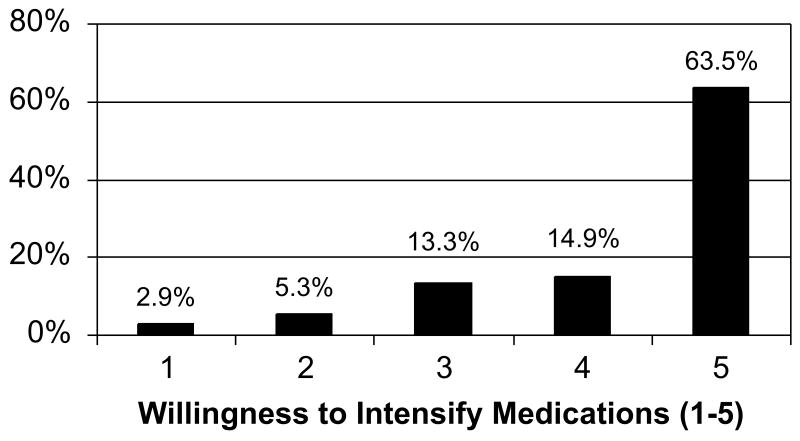

Figure 1 shows the distribution of responses on our primary outcome measure, patients’ reported willingness to intensify their BP medications if asked to do so by their primary care provider. 64% had no reservations about intensifying medications (which we recoded as full willingness to intensify), while 36% expressed at least some degree of unwillingness to intensify medications.

Figure 1.

Reported willingness to intensify medications

Table I reports participants’ characteristics and responses to survey items, broken down by reported willingness to intensify medications, while Table II presents the results of our ordered logistic regression analysis. Of interest, current BP control was not associated with participants’ willingness to intensify their medication regime in response to an elevated BP level. Neither systolic BP recorded at the index visit, average systolic BP over the prior year, nor patients’ description of how high their BP is “on average” were related to reported willingness to intensify.

Table I.

Patient characteristics and survey responses, by reported willingness to intensify medications

| Patient Characteristic or Survey Response | Willingness to Intensify (WTI) | |

|---|---|---|

| WTI < 5 (n=372) | WTI = 5 (n=648) | |

| BP Control | ||

| Visit systolic BP (mm Hg: mean) | 147.8 | 147.2 |

| Average prior year systolic BP (mm Hg: mean) | 144.9 | 144.6 |

| Rated BP levels “on average” to be “slightly high” or worse (# [%]) | 279 [77%]* | 448 [71%] |

| Self-Efficacy re: BP control | ||

| Understand what need to do to control BP (1-5: mean)a | 3.00* | 3.20 |

| Confidence in ability to manage BP (1-5: mean)a | 3.39 | 3.46 |

| Feel capable of handling BP (1-5: mean)a | 3.40* | 3.56 |

| Meet challenge of controlling BP (1-5: mean)a | 3.47* | 3.63 |

| Importance of BP control | ||

| Concern regarding BP = 140/90 (1-4: mean)a | 2.39* | 3.49 |

| Concern regarding BP = 165/95 (1-4: mean)a | 3.22* | 3.32 |

| Need to intervene for BP = 140/90 (1-4: mean)a | 2.20* | 2.07 |

| Competing Demands | ||

| Glycemic issues | ||

| Think about BP > blood sugar (BS) in daily life (# [%]) | 69 [20%] | 134 [22%] |

| BP more likely than BS to lead to heart attack (# [%]) | 267 [76%] | 504 [81%] |

| Scenario question: chose BP > BS (# [%]) | 228 [63%] | 407 [65%] |

| Ranked BP more important than BS (# [%]) | 105 [30%] | 187 [30%] |

| Chronic pain >6 months in last year (# [%]) | 213 [60%] | 357 [58%] |

| Depression | ||

| Little interest/pleasure in doing things (1-4: mean)a | 1.85 | 1.78 |

| Felt down, depressed, hopeless (1-4: mean)a | 1.70 | 1.66 |

| Have more pressing issues than health (1-5: mean)a | 2.22* | 1.98 |

| Medication Issues | ||

| Number of medication classes taken (mean) | 5.7* | 6.2 |

| Concern about side effects | ||

| Worry about side effects from BP meds (1-5: mean)a | 3.39* | 3.04 |

| Overall concern about medication side effects (1-5: mean)a | 3.22* | 2.41 |

| Adherence/management | ||

| Agree/Disagree: Forget medications (1-5: mean)a | 2.87* | 2.57 |

| Agree/Disagree: Alter does to suit own needs (1-5: mean)a | 2.06* | 1.72 |

| Frequency: Forget medications (1-5: mean)a | 2.22* | 2.06 |

| Frequency: Miss or adjust does to suit own needs (1-5: mean)a | 1.82* | 1.59 |

| Difficulty managing current medications (1-5: mean)a | 2.04* | 1.54 |

| Took less meds due to cost within last year (# [%]) | 58 [16%]* | 46 [7%] |

| Perceived dependence on BP medications | ||

| Without BP medications, would be very ill (1-5: mean)a | 3.39* | 3.04 |

| Future health depends on BP medications (1-5: mean)a | 3.50* | 3.71 |

| Provider-Patient Relationship | ||

| Trust in provider | ||

| Trust doctor's judgments (1-5: mean)a | 3.92* | 4.21 |

| Doctor cares about costs more than my health b (1-5, mean)a | 2.15* | 1.87 |

| Overall trust in doctor (0-10: mean)a | 8.02* | 8.53 |

| Covariates | ||

| Age (mean) | 65.1 | 65.5 |

| Non-caucasian race/ethnicity (# [%]) | 101 [27%] | 147 [23%] |

| Married/partner (# [%]) | 229 [62%] | 406 [63%] |

| Education (# > high school [%]) | 175 [48%] | 296 [46%] |

| Income (# ≤ $40,000/yr [%]) | 301 [89%] | 549 [90%] |

Notes:

Higher scores reflect higher agreement with the statement (e.g., higher concern, etc.)

Item is reverse coded for inclusion in the trust in provider scale.

p<0.05 vs. WTI=5 group using t-tests (scale variables) or chi-squared tests (binary variables).

Table II.

Multivariate ordered logistic regression model of factors associated with willingness to intensify blood pressure (BP) medications

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| BP Control | ||

| Visit systolic BP a | 1.01 [0.91, 1.11] | 0.91 |

| Average prior year systolic BP a | 1.01 [0.92, 1.12] | 0.77 |

| Rating of BP levels “on average” | 0.98 [0.79, 1.22] | 0.87 |

| Self-Efficacy re: BP control | ||

| Self-efficacy/knowledge | 1.00 [0.83, 1.20] | 0.99 |

| Importance of BP control | ||

| Concern/intervene if high BP | 1.17 [0.99, 1.40] | 0.07 |

| Competing Demands | ||

| Glycemic issues | 1.04 [0.84, 1.28] | 0.74 |

| Pain | 0.93 [0.70, 1.24] | 0.64 |

| Depression | 1.07 [0.91, 1.25] | 0.42 |

| Other pressing issues | 0.89 [0.79, 1.01] | 0.07 |

| Medication Issues | ||

| Number of medication classes taken | 1.02 [0.99, 1.07] | 0.19 |

| Concern about side effects | 0.49 [0.42, 0.59] | <0.001 |

| Adherence/management | 0.72 [0.57, 0.91] | 0.006 |

| Self-restriction due to cost | 0.76 [0.49, 1.16] | 0.20 |

| Perceived dependence on BP medications | 1.50 [1.26, 1.79] | <0.001 |

| Provider-Patient Relationship | ||

| Trust in provider | 1.30 [1.10, 1.54] | 0.002 |

| Covariates | ||

| Age | 0.99 [0.98, 1.00] | 0.14 |

| Non-caucasian race/ethnicity | 0.83 [0.59, 1.16] | 0.27 |

| Married/partner | 0.86 [0.65, 1.15] | 0.32 |

| Education | 0.99 [0.82, 1.20] | 0.93 |

| Income | 1.15 [0.86, 1.55] | 0.36 |

Notes: N=1,062, with missing data imputed using multiple imputation via chained equations (MICE) methods. Table reports combined results of ordered logistic regressions performed over the set of 5 replicates.

Systolic BP levels were divided by 10 mm Hg to facilitate interpretation.

Our index of patient BP-specific self-efficacy and knowledge had a similar lack of correlation with our dependent variable. Patients who perceived themselves to be knowledgeable about what they needed to do to control their BP levels were no more likely to be willing to intensify their medications than patients with low BP knowledge / self-efficacy. It is not that patients thought that BP control was an unimportant goal, however. Responses to our questions that assessed the importance of intervening for elevated BP levels showed a trend in the expected direction – greater perceived importance of BP control correlated with increased willingness to intensify medications – although the effect did not reach statistical significance in the multivariate model (OR=1.17, 95% C.I.: 0.99, 1.40).

We also assessed four types of competing demands: glycemic control issues, chronic pain, depression, and non-medical pressing issues in patients’ lives. Table II shows, however, that none of these measures of competing demands had significant independent correlation with patients’ willingness to intensify their BP medications. The strongest trend occurred for our question assessing whether “other pressing issues” in the patient's life impeded their ability to focus on medical concerns, yet this effect is also not statistically significant (OR=0.89, 95% C.I.: 0.79, 1.01).

By contrast with both our BP-focused and competing demand measures, our measures of medication related issues showed consistently significant correlations with patients’ willingness to intensify their BP medications. While the number of medication classes prescribed to the patient was unrelated to reported willingness to intensify, concern regarding medication side effects (both for all medications and specifically regarding BP medications) had the strongest negative association with reported willingness to intensify of any factor tested (OR=0.49, 95% C.I.: 0.42, 0.59). If patients reported difficulty adhering to their current medication regime and/or difficulty managing their medications (as measured by our standardized scale), they were similarly unwilling to consider adding a new medication (OR=0.72, 95% C.I.: 0.57, 0.91). Patients who reported having to restrict the amount of medications they took due to cost were also somewhat less likely to be willing to add a new medication (OR=0.76, 95% C.I.: 0.49, 1.16), although the trend did not achieve statistical significance. Lastly, if patients perceived their health as dependent on BP medications, they were more willing to add a new medication upon the recommendation of their provider (OR=1.50, 95% C.I.: 1.26, 1.79).

As hypothesized, the relationship between the patient and his or her health care provider is also a key factor in determining patients’ willingness to consider medication intensification. Our composite measure of trust in physician was significantly associated with willingness to intensify (OR=1.30, 95% C.I.: 1.10, 1.54). However, none of the patient demographic characteristics measured showed significant correlations with our dependent variable.

To illustrate the effect that medication issues have on patients’ willingness to intensify medications, we calculated predicted probabilities for each level of willingness to intensify medications based on different levels of medication concerns. In a baseline scenario that set our standardized scales for concern over medication side effects, difficulty managing medications, and dependence on BP medications to 0, defined no medication restriction due to cost, and set all other variables to their median values, we predicted that 66.6% (95% C.I.: 61.2%, 72.1%) would have “no problem at all” intensifying medications. Taken individually, a 1 standard deviation increase in the side effects scale drops this percentage to 49.7% (95% C.I.: 42.3%, 57.0%), a similar increase in the medication management scale drops it to 59.0% (95% C.I.: 50.5%, 67.4%), a 1 standard deviation reduction in perceived dependence on BP medication lowers it to 57.0% (95% C.I.: 49.6%, 64.5%), and a positive response to medication restriction due to cost drops the percentage with no problems intensifying to 60.1% (95% C.I.: 49.3%, 70.9%). However, when all four of these medication concerns occur simultaneously, the effect of is more substantial, reducing the predicted proportion of study participants with full willingness to intensify BP medications all the way to 26.3% (95% C.I.: 15.5%, 37.1%).

Conclusions

According to our survey of more than 1,000 VA patients who had both diabetes mellitus and elevated visit BP readings, the most significant factor that determined treated hypertensive patients’ willingness to consider intensification of BP medications in response to an elevated BP level was how well that patient was tolerating and managing his or her current medication regime. Patients appeared most comfortable with the concept of adding new medications when they experienced few problems with existing medications, felt that their health was dependent on taking BP medications, and trusted their health care provider. This finding is consistent with prior research that patients who experience significant side effects or have difficulty sticking to their dosing schedule are more ambivalent about taking their medications,[33, 34], claims data that support the idea that non-adherent patients are less likely to have their therapy intensified,[35] and prior research on patients who perceive their health as integrally dependent on their medication therapies.[36]

Self-restriction of medication use due to cost, however, was not significantly associated with willingness to intensify within our veteran population. In addition, neither patient perceptions of their BP levels nor their self-efficacy in controlling BP appeared to have influence on their willingness to intensify. This result is important because it suggests that many efforts to educate patients about the need for hypertension management may be “holding the wrong hand.” Even patients who fully grasp the importance of BP control and who are fully aware of what they need to do to achieve BP control may nonetheless be unwilling to consider medication intensification if there are unresolved issues regarding existing medications. While our cross-sectional data cannot show causal relationships, we speculate that focused efforts to identify patients who are non-adherent, experiencing significant side effects, or facing cost constraints could lead to not only resolution of the existing problems but also possible increased acceptance of provider recommendations regarding additional needed interventions.

An additional important finding of our research is the significant association of patient trust in physician with reported willingness to intensify. This association suggests that the quality of the patient-physician relationship does influence patients’ attitudes about receiving additional medications, a finding that is quite consistent with recent research that suggests that paternalistic physicians have greater difficulty than more patient-centered physicians in helping hypertensive patients reach BP control goals.[37] Further research is needed to assess whether interventions designed to help clinicians bring patient concerns about existing medications to the forefront of hypertension discussions would also result in greater patient acceptance of medication intensification when it is needed to improve BP control.

There are several key limitations to our findings. First, the VA patient population from which we drew our participants is a distinct demographic with many unique characteristics (e.g., predominantly male) which may interact with willingness to consider medication intensification. For example, cost of medications may be more relevant to patient acceptance of new medications in a non-VA population than it was in our sample. Second, our survey methodology relied upon patient self-reports for almost all data, including our dependent measure of willingness to intensify. It is certainly possible that what patients say they would do on a survey may differ in key ways from patients’ cognitive and emotional reactions in the context of actual clinical consultations. Third, the scale regarding issues related to glycemic control had the lowest reliability of our scale variables, which may have limited our ability to find related effects.

Nevertheless, the clear dominance of medication-related factors over other issues in our analysis leads us to recommend that clinicians redouble their efforts to monitor and address patient concerns regarding ongoing medication regimes.[38] For the veterans we surveyed, consideration of new interventions appeared to be tightly linked to assessment of the status of current ones. If existing BP medications were deemed necessary, manageable, and without side effects, patients were much more open to new additions than if current BP medications were seen as burdensome, inconsistently taken, too costly, or nonessential. Attention to pre-existing medication concerns has the potential to improve both BP control and downstream outcomes while simultaneously improving patient satisfaction with care.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this research were presented at the U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) National Meeting, Washington, D.C., February 22, 2007. Financial support for this study was provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, HSR&D Service (IIR 02-225). This work was also supported in part by the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center Grant P60DK-20572 from the NIDDK of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zikmund-Fisher is supported by a career development award from the American Cancer Society (MRSG-06-130-01-CPPB). The funding agreements ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, and publishing the report. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the University of Michigan. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Saaddine JB, Cadwell B, Gregg EW, Engelgau MM, Vinicor F, Imperatore G, Narayan KMV. Improvements in Diabetes Processes of Care and Intermediate Outcomes: United States, 1988-2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006 April 4;144:465–74. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hiatt L, Adams J, Hicks J, Decristofaro A, Chen R, Lapuerta P, Kerr E. Quality of care for hypertension in the United States. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vijan S, Hayward RA. Treatment of Hypertension in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Blood Pressure Goals, Choice of Agents, and Setting Priorities in Diabetes Care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:593–602. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-7-200304010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Hickey EC, Glickman M, Friedman R, Kader B. Hypertension Management in Patients With Diabetes: The need for more aggressive therapy. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:355–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hicks PC, Westfall JM, Van Vorst RF, Bublitz Emsermann C, Dickinson LM, Pace W, Parnes B. Action or Inaction? Decision Making in Patients With Diabetes and Elevated Blood Pressure in Primary Care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2580–5. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godley PJ, Maue SK, Farrelly EW, Frech F. The Need for Improved Medical Management of Patients with Concomitant Hypertension and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:206–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaars CF, Denig P, Kasje WN, Stewart RE, Wolffenbuttel BHR, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Physician, Organizational, and Patient Factors Associated With Suboptimal Blood Pressure Management in Type 2 Diabetic Patients in Primary Care. Diabetes Care. 2004 January 1;27:123–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, Doyle JP, El-Kebbi IM, Gallina DL, Miller CD, Ziemer DC, Barnes CS. Clinical Inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:825–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Connor PJ. Overcome Clinical Inertia to Control Systolic Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2677–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine LJ, Cutler JA. Hypertension and the Treating Physician: Understanding and Reducing Therapeutic Inertia. Hypertension. 2006;47:319–20. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000200692.23410.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okonofua EC, Simpson KN, Jesri A, Rehman SU, Durkalski VL, Egan BM. Therapeutic Inertia Is an Impediment to Achieving the Healthy People 2010 Blood Pressure Control Goals. Hypertension. 2006 March 1;47:345–51. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000200702.76436.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr EA, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Klamerus ML, Subramanian U, Hogan MM, Hofer TP. The role of clinical uncertainty in treatment decisions for diabetic patients with uncontrolled blood pressure. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:717–27. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedner T, Falk M. Physician and patient evaluation of hypertension-related risks and benefits from treatment. Blood Press Suppl. 1997;1:26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egan BM, Lackland DT, Cutler NE. Awareness, knowledge, and attitudes of older americans about high blood pressure: implications for health care policy, education, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:681–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.6.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight EL, Bohn RL, Wang PS, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J. Predictors of uncontrolled hypertension in ambulatory patients. Hypertension. 2001;38:809–14. doi: 10.1161/hy0901.091681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nutting P, Baier M, Werner J, Cutter G, Conry C, Steward L. Competing demands in the office visit: What influences mammography recommendations? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:352–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redelmeier D, Tan S, Booth G. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1516–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, Coyne J, Cooper-Patrick L, Rubenstein L. The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9 doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moser M. No surprises in blood pressure awareness study findings: we can do a better job. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:654–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.6.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safford MM, Shewchuk R, Qu H, Williams JH, Estrada CA, Ovalle F, Allison JJ. Reasons for not intensifying medications: differentiating “clinical inertia” from appropriate care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1648–55. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0433-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian U, Hofer TP, Klamerus ML, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Heisler M, Kerr EA. Knowledge of blood pressure targets among patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2007;1:195–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1644–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krein SL, Heisler M, Piette JD, Butchart A, Kerr EA. Overcoming the influence of chronic pain on older patients' difficulty with recommended self-management activities. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:61–8. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krein SL, Heisler M, Piette JD, Makki F, Kerr EA. The effect of chronic pain on diabetes patients' self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:65–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corson K, Gerrity MS, Dobscha SK. Screening for depression and suicidality in a VA primary care setting: 2 items are better than 1 item. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:839–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire: The development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piette JD, Heisler M, Wagner TH. Cost-related medication underuse among chronically ill adults: the treatments people forgo, how often, and who is at risk. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1782–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, Rogers WH, Taira DH, Lieberman N, Ware JE. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36:728–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stata Statistical Software. 10. College Station, Texas: Stata Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Tech J. 2005;5:527–36. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Long JS, Freese J. Regression Models for Categorical Outcomes Using Stata. 2nd. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benson J, Britten N. What effects do patients feel from their antihypertensive tablets and how do they react to them? Qualitative analysis of interviews with patients. Fam Pract. 2006;23:80–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benson J, Britten N. Patients' decisions about whether or not to take antihypertensive drugs: qualitative study. BMJ. 2002;325:873. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7369.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant RW, Singer DE, Meigs JB. Medication adherence before an increase in antihypertensive therapy: a cohort study using pharmacy claims data. Clin Ther. 2005;27:773–81. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benson J, Britten N. Patients' views about taking antihypertensive drugs: questionnaire study. BMJ. 2003;326:1314–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7402.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nwachuku CE, Bastien A, Cutler JA, Grob GM, Margolis KL, Roccella EJ, Pressel S, Davis BR, Caso M, Sheps S, Weber M. Management of high blood pressure in clinical practice: perceptible qualitative differences in approaches utilized by clinicians. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:822–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heisler M, Hogan MM, Hofer TP, Schmittdiel JA, Pladevall M, Kerr EA. When more is not better: treatment intensification among hypertensive patients with poor medication adherence. Circulation. 2008;117:2884–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.724104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]