Abstract

A treatment gap exists between the efficacious treatments available for patients with bipolar disorder and the usual care these patients receive. This article reviews the evolution of the collaborative care treatment model, which was designed to address treatment gaps in chronic medical care, and discusses the efficacy of this model when applied to improving outcomes for patients with bipolar disorder in the primary care setting. Key elements of collaborative care include the use of evidence-based treatment guidelines, patient psychoeducation, collaborative decision-making with patients and with other physicians, and supportive technology to facilitate monitoring and follow-up of patient outcomes. Integrating psychiatric and medical health care can assist in achieving the goal of bipolar disorder treatment, which is full functional recovery for patients.

Treating patients with bipolar disorder poses challenges for primary care and specialty care physicians alike. Diagnosing bipolar disorder can be difficult due to the often confusing presentation of the illness and can be further complicated by patient denial, a consequence of the perceived stigma associated with psychiatric diagnoses. Structural issues in health care such as insurance limitations on specialty care and the lack of specialty providers available also impact care. The medical management of patients with bipolar disorder is generally complicated by both medical and psychiatric comorbidities, and complex medication regimens and their associated side effects can lessen treatment adherence by patients. These and other factors contribute to a gap between the efficacy of treatments available for bipolar disorder and the effectiveness of the actual care most patients receive.

The disparity between the health care services available and the care that patients usually receive is not unique to bipolar disorder. Numerous studies have documented treatment gaps in medical care, both in administration and in outcomes, particularly in managing chronic illnesses.1

IMPROVING CARE FOR PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC ILLNESS

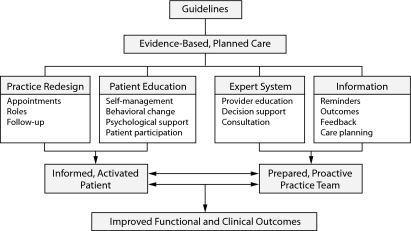

In an early effort to address gaps in health care services, Wagner, Austin, and Von Korff2,3 reviewed the literature to determine the shared characteristics of successful approaches to improving the outcomes of patients with chronic illnesses (Figure 1). Their findings suggested a need to reorganize the current model of primary health care, which they described as geared toward acute care (ie, short patient visits designed to diagnose and treat symptoms, with little patient education and a reliance on laboratory tests, prescriptions, and patient-initiated follow-up). Instead, a planned approach to chronic care using evidence-based guidelines and protocols to support patient participation and self-management was recommended, along with incorporating information systems that support disease registries, reminder systems, and continuity of care.4

Figure 1.

Improving Outcomes in Chronic Illnessa

aAdapted with permission from Wagner et al.2

Von Korff and colleagues5 next focused on collaborative management (ie, collaboration between the physician and patient), a model in which health care providers strengthen and support self-care by patients with chronic illness and their family members, who often become caregivers, while ensuring that necessary health care services are provided at appropriate intervals. Using behavioral principles and empirical evidence on effective self-care, Von Korff et al5 identified 4 main elements of successful collaborative care for chronic illness: (1) a collaborative definition of problems (that is, a definition that incorporates both physician-perceived and patient-perceived problems); (2) joint goal setting (which targets specific problems and creates an action plan); (3) the provision of individualized patient training and support services, including educational materials, emotional support, and structured programs; and (4) sustained follow-up to monitor and reinforce progress, identify potential complications, or make needed modifications to the patient's health care plan.

A recent concept that encompasses many of the elements of the collaborative care model for the chronically ill is the patient-centered medical home. In this model, physicians lead a team that is collectively responsible for all of a patient's health care needs, including arranging specialist care or services outside the physician's practice. The approach encourages active participation by the patient by ensuring communication between the patient and members of the treatment team (eg, by providing better access through expanded hours and open access scheduling). To be recognized as a patient-centered medical home by the National Committee for Quality Assurance,6 a practice must meet certain standards regarding aspects of care that have been established by medical specialty organizations. Aspects of care that are measured include access and communication, patient registry and tracking functions, care management, patient self-management support, electronic prescribing, test tracking, referral tracking, performance improvement and reporting, and advanced electronic communications. The practice must also implement evidence-based guidelines for chronic conditions.

For Clinical Use

♦ Collaborative care models have shown efficacy in improving outcomes when treating patients with bipolar disorder.

♦ Collaborative care models encourage knowledgeable patient self-management of the illness.

♦ Key elements of collaborative care (and cornerstones of the patient-centered medical home) include a clinical team approach, patient education and participation in decision-making, evidence-based guidelines, and a system to facilitate planned follow-up and monitor outcomes.

COLLABORATIVE CARE IN MENTAL HEALTH

Elements of the collaborative care model for treating chronic illness can be applied to mental health care generally and to care for bipolar disorder in particular. Collaborative care treatment models have been shown to improve outcomes over those of standard care among patients treated for depression in primary care settings, with studies showing benefits for up to 5 years.7 These studies included models of collaboration not only between the physician and patient but also among primary care physicians, specialists, and other health professionals such as nurse practitioners, psychologists, and social workers.

Craven and Bland8 reviewed the literature to identify best practices for promoting effective outcomes in collaborative mental health care. Their analysis of 38 studies, usually in major depressive disorder, showed that successful collaboration between primary care and specialty care providers requires preparation, time to develop, and supportive structures (eg, institutional and staff “buy-in”). Successful collaborative care arrangements grow out of preexisting relationships between physicians who have met in person and work best for both the physicians and the patients when the physicians work in the same location, especially one that is familiar and nonstigmatizing for patients. Studies with high or moderate levels of collaboration between physicians showed positive patient outcomes most often, but some studies with lesser degrees of physician collaboration also had positive patient outcomes. Studies pairing collaboration with the use of treatment guidelines generally showed greater benefits than either intervention alone (particularly for patients with more severe depression). Other factors that predicted better outcomes included systematic follow-up and enhanced patient education. Giving patients treatment choices (eg, psychotherapy versus medication) may help to engage patients in the collaborative care process.

Harkness and Bower9 reviewed studies in which mental health workers provided psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions in primary care settings in order to determine the effect on the clinical behavior of the primary care providers. The review found reductions in primary care provider consultations, prescribing costs, psychotropic prescribing, and referrals to specialty providers. Although onsite mental health care may allow more care to be given within the patient-centered medical home and may lessen psychotropic prescribing and cost, the review found the changes modest in magnitude and their economic impact unclear.

Thielke and colleagues10 reviewed the literature to evaluate different strategies for improving mental health care outcomes in the primary care setting. The strategies reviewed included systematized screening for mental health conditions, provider education and training, dissemination of treatment guidelines, increased referral to mental health specialists, locating mental health specialists in primary care settings, and tracking mental health outcomes. The authors concluded that the individual strategies had little positive effect separately, but that organized collaborative care between mental health and primary care providers did generally result in better outcomes for patients. Two key differences between usual primary care and collaborative care were identified: proactive follow-up and systematic tracking of outcomes to allow for informed treatment decisions and the use of care managers, supervised by mental health specialists, to facilitate treatment initiated by the primary care provider (Table 1).10

Table 1.

Core Processes and Provider Roles in Collaborative Carea

| Providers | ||||

| Process | Care Manager | Mental Health Expert | Primary Care Provider | Information Tracking and Exchange |

| Systematic diagnosis and tracking of outcomes | Measure, document, and track mental health outcome | Supervise case-loads with care managers, based on measured outcomes | Receive feedback from care managers about outcomes | Database of symptom severity over time for all patients |

| Consult on diagnosis for difficult cases | ||||

| Stepped care: | ||||

| a) Changes to treatment using evidence-based algorithm if patient is not improving | Educate about medications and their use; encourage adherence Counsel patients Facilitate treatment change or referral to mental health as clinically indicated |

Consult on patients who are not improving as expected Recommend additional treatments or referral to specialty mental health care according to evidence-based guidelines |

Prescribe medications Reinforce and support treatment plan Collaborate with mental health expert and care manager to make necessary treatment changes |

Treatments received Changes to treatment |

| b) Relapse prevention once patient is improved | Track symptoms after initial improvement; follow algorithms | No formal role during maintenance phase | Reinforce relapse prevention plan | Reminders to ensure ongoing contact and symptom monitoring |

Reprinted with permission from Thielke et al.10

Collaborative Care in Bipolar Disorder

Several studies have examined the use of collaborative care specifically in treating patients with bipolar disorder. In one of the earliest studies,11 which was conducted in the Bipolar Disorders Program at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Rhode Island, clinical nurse specialists were assigned to patients (N = 76) as their primary mental health caregiver. The nurses, working with a supervising psychiatrist, delivered patient education about the meaning of the illness and its effect on patients' actions, initiated follow-up with patients, and served as a contact for all of their mental health needs, including crisis management, specialty care, and inpatient services. After 6 months, measurements showed increases in patient satisfaction with care and in intensity of medication treatment, while emergency department visits, psychiatric triage use, and inpatient days all decreased.

Simon and colleagues12 conducted a 2-year study of collaborative care for bipolar disorder at the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound (N = 441). In their model, nurse care managers provided group psychoeducation, monitored mood symptoms and medication adherence by monthly telephone calls, provided feedback to the treating mental health care providers, facilitated follow-up care, and provided crisis intervention. The results showed that the intervention significantly reduced the frequency (P = .01) and the severity (P = .04) of mania symptoms for the study population compared with those who received standard care but did not significantly affect the symptoms of depression.

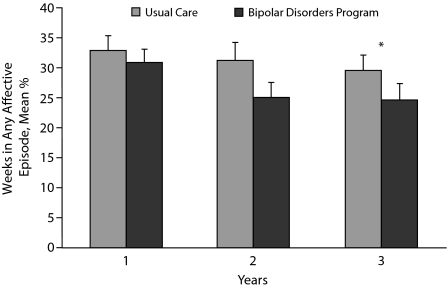

In a 3-year, multisite trial, Bauer and colleagues13,14 randomly assigned patients to an intervention program in the Bipolar Disorders Program at the VA (n = 166) or to usual care at the VA (n = 164). In the intervention, treatment guidelines were used to support providers in their decision making and psychiatric clinical nurse specialists acted as coordinators to ensure continuity of care, facilitate access to care, and provide the psychiatrist with information and reminders regarding guideline-based treatment and monitoring. The intervention also included group psychoeducation using the Life Goals Program,15 a manual-based program that educates patients regarding personal symptom profiles, warning symptoms, and triggers and helps the patient to address coping and life management issues with ongoing group psychotherapy. This intervention, as in the Simon et al12 study, significantly reduced the number of weeks spent in any affective episode compared with usual care (P = .041), primarily due to a reduction in mania (Figure 2).14 Social role dysfunction decreased significantly (P = .003) for intervention participants compared to patients in usual care, and mental (but not physical) quality of life significantly improved (P = .01). Treatment satisfaction was significantly higher (P < .001) for patients in the intervention group. The intervention was cost-neutral.

Figure 2.

Mean Weeks (%) in Any Affective Episode for Patients in the Veterans Affairs (VA) Bipolar Disorders Program and Patients Receiving Usual VA Care for Bipolar Disordera

aReprinted with permission from Bauer et al.13

*P = .041.

In 2009, Kilbourne and colleagues16 reanalyzed data from the Bauer et al14 study to determine whether the collaborative care model was equally effective for patients with substance use, anxiety, psychosis, and other psychiatric and/or medical comorbidities. They found comparable treatment effects between participants with and without these comorbidities. However, they noted that the treatment effect on physical health, which in the original study was found to be not significantly different overall from patients in usual care, was blunted in patients with cardiovascular-related comorbidity, suggesting a need to address physical health care in the collaborative model, particularly in relation to patients with cardiovascular-related risks.

KEY ELEMENTS OF SUCCESSFUL COLLABORATIVE CARE IN BIPOLAR DISORDER

Additional efforts to identify effective strategies for enhancing the treatment of bipolar disorder include the STAndards for BipoLar Excellence (STABLE) Project17 and the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD).18 STABLE was an initiative created to identify, develop, and test evidence-based performance measures to improve the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in primary and specialty care settings. STABLE also developed a free resource toolkit to support and facilitate the adoption and use of these measures, which is available at www.cqaimh.org/stable_toolkit.html. Williams and Manning19 identified 5 of the performance measures developed by the STABLE Project as being particularly relevant for collaborative care in bipolar disorder: (1) assessment for suicide risk, (2) assessment for substance use/abuse, (3) monitoring for extrapyramidal symptoms, (4) monitoring of metabolic parameters such as hyperglycemia or hyperlipidemia, and (5) provision of bipolar-specific education and information to the patient.

Similarly, the STEP-BD study demonstrated that integrating systematic monitoring and measurement tactics into treatment enables clinicians and patients to collaborate in making decisions about care.18 The use of measurement data informs not only physicians but also patients, providing patients with individualized education about their illness course and its treatment. Along with the measurement-based collaborative care model, the STEP-BD protocol trained clinicians in using clinical practice guidelines and was able to demonstrate higher rates of guideline-concordant care than those found in usual care.20

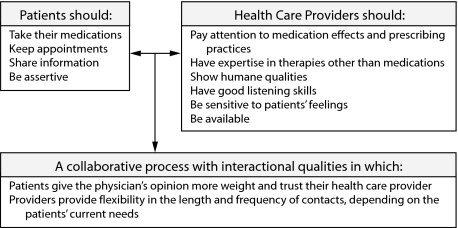

Sajatovic and colleagues21 investigated the patient's perspective on the components necessary for a successful collaborative patient-provider relationship by querying a subset of patients enrolled in the Life Goals Program (N = 52).13,14 Patients cited specific responsibilities for the patient and the provider, along with a strong emphasis on the interactional component between the patient and the provider (Figure 3). Key responsibilities of the patient include keeping appointments and taking medication, while the provider must listen to the patient and allow enough time for each appointment. In the same study, which lasted 2 years, effective clinician strategies for operationalizing the key elements of the provider functions of a successful collaborative model were delineated. Clinician strategies included educating the patient about bipolar disorder and its treatments; encouraging the patient to participate fully in identifying their own personal symptoms, treatment goals, and progress; maximizing easy access to care and continuity of care; and providing group or individual psychotherapy to work through issues such as stigma.22

Figure 3.

Key Elements of a Positive Collaborative Experience as Expressed by Individuals With Bipolar Disordera

aBased on Sajatovic et al.21

Because a successful collaboration between physician and patient requires the patient to come to appointments and maintain treatment adherence, the effect on adherence by the Life Goals Program versus usual care for patients with bipolar disorder was also examined (N = 164). Preliminary data22 from the 3-month and 6-month follow-ups indicated that patients participating in the Life Goals intervention experienced significantly greater improvement in attitudes toward medication compliance and in symptom severity (P = .015 for both), as well as increased global function as measured by clinician ratings, indicating that the collaborative model facilitated treatment adherence. However, final results23 from the 12-month follow-up indicated no difference between groups; attendance in the Life Goals Program sessions was low, and a trend was found indicating that greater depressive severity at baseline was associated with more negative attitudes toward treatment over time.

NEW GOALS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The goal of treatment for patients with bipolar disorder has changed in recent years from one of symptom abatement to one of recovery—that is, returning patients to their level of functioning prior to the onset of illness.24 The model of treatment has also changed from a provider-focused perspective to a team-based and patient-oriented perspective. Patients are provided with education and information about their illness that allows them to participate in their own treatment through informed decision-making and collaboration with the clinician. In addition, the integration of mental health services and primary care services allows treatment of the whole patient. For example, patients prescribed psychiatric medications can be monitored not only for psychiatric response to the agents but also for overall health-related responses such as metabolic changes or weight gain.

The aims of integrated health care models include improving patient access to care, improving patient outcomes by increasing the use of evidence-based care strategies, and delivering the most value for the services rendered.25 However, many questions remain about best practices in collaborative care. For example, which patients should receive this kind of care—those with the most severe illness or all patients with bipolar disorder? Would patients with bipolar II disorder receive more value from the collaborative model than a patient with cyclothymia? To limit costs, can interventions be scaled down for patients with less severe chronic illness or for practices that serve fewer patients with chronic illnesses?

How to replicate collaborative models in the typical primary care practice as opposed to closed-model health maintenance organizations is another important question. Translating collaborative interventions into widely used, real-world practices may depend on reimbursement and health care system changes that are still being debated.

Despite some questions, certain aspects of collaborative care, such as adopting the concept of patient-centered treatment focusing on recovery, can easily be fostered. Health care teams consisting of primary care providers, mental health specialists, psychiatrists, social workers, psychiatric nurse specialists, case managers, and pharmacists should be developed. Primary care physicians can develop relationships with specialists for consultation and rapid referrals when necessary, such as in cases of suicidality. Evidence-based treatment guidelines have been created for the treatment of bipolar disorder and can easily be incorporated into treatment plans. Registries to assist in planned follow-up and tracking of patient outcomes may be the single most important element in improving practice systems to better manage patients with bipolar disorder, especially those who have barriers to adherence.

Providers should also incorporate routine mental assessment of patients into their practices, as seen in the STABLE and STEP-BD programs. These routine assessments should include symptoms, adherence, suicidality, psychiatric comorbidities such as substance use, and side effects of medications such as metabolic syndrome. In addition, psychoeducation, psychosocial and family support, peer support, and formal counseling will assist patients in the self-management of their illness. Incorporating the critical elements of collaborative care into patient treatment plans has shown efficacy in improving outcomes over usual care.

Disclosure of off-label usage: The author has determined that, to the best of his knowledge, no investigational information about pharmaceutical agents that is outside US Food and Drug Administration-approved labeling has been presented in this activity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wagner EH. Managed care and chronic illness: health services research needs. Health Serv Res. 1997;32(5):702–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Manag Care Q. 1996;4(2):12–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer JK, et al. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(12):1097–1102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Physician Practice Connections–Patient-Centered Medical Home. http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/631/Default.aspx. Accessed January 12, 2010.

- 7.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craven MA, Bland R. Better practices in collaborative mental health care: an analysis of the evidence base. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(suppl 1):7S–72S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harkness EF, Bower PJ. On-site mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions to patients in primary care: effects on the professional practice of primary care providers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;Jan 21(1):CD000532. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000532.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thielke S, Vannoy S, Unützer J. Integrating mental health and primary care. Prim Care. 2007;34(3):571–592. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shea NM, McBride L, Gavin C, et al. The effects of an ambulatory collaborative practice model on process and outcome of care for bipolar disorder. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 1997;3(2):49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Bauer MS, et al. Long-term effectiveness and cost of a systematic care program for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):500–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. for the Cooperative Studies Program 430 Study Team. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part I. Intervention and implementation in a randomized effectiveness trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):927–936. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. for the Cooperative Studies Program 430 Study Team. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part II. Impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):937–945. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer MS, McBride L, Chase C, et al. Manual-based group psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: a feasibility study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;55(9):449–455. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilbourne AM, Biswas K, Pirraglia PA, et al. Is the collaborative chronic care model effective for patients with bipolar disorder and co-occurring conditions? J Affect Disord. 2009;112(1-3):256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Center for Quality Assessment and Improvement in Mental Health. STABLE performance measures. http://www.cqaimh.org/stable_measures.html. 2007. Accessed January 18, 2010.

- 18.Nierenberg AA, Ostacher MJ, Borrelli DJ, et al. The integration of measurement and management for the treatment of bipolar disorder: a STEP-BD model of collaborative care in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 11):3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams JW, Jr, Manning JS. Collaborative mental health and primary care for bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2008;14(suppl 2):55–64. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000320127.84175.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dennehy EB, Bauer MS, Perlis RH, et al. Concordance with treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder: data from the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40(3):72–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sajatovic M, Davies M, Bauer MS, et al. Attitudes regarding the collaborative practice model and treatment adherence among individuals with bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46(4):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies MA, McBride L, Sajatovic M. The collaborative care practice model in the long-term care of individuals with bipolar disorder: a case study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15(8):649–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sajatovic M, Davies MA, Ganocy SJ, et al. A comparison of the life goals program and treatment as usual for individuals with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(9):1182–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.9.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stotland NL, Mattson MG, Bergeson S. The recovery concept: clinician and consumer perspectives. J Psychiatr Pract. 2008;14(suppl 2):45–54. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000320126.76552.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hine CE, Howell HB, Yonkers KA. Integration of medical and psychological treatment within the primary health care setting. Soc Work Health Care. 2008;47(2):122–134. doi: 10.1080/00981380801970244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]