Abstract

Findings from a large, randomized controlled trial of couple education are presented in this brief report. Married Army couples were assigned to either PREP for Strong Bonds (n = 248) delivered by Army chaplains or to a no-treatment control group (n = 228). One year after the intervention, couples who received PREP for Strong Bonds had 1/3 the rate of divorce of the control group. Specifically, 6.20% of the control group divorced while 2.03% of the intervention group divorced. These findings suggest that couple education can reduce the risk of divorce, at least in the short run with military couples.

Keywords: Couple education, Marriage education, Divorce, Army couples, Randomized controlled trial

While divorce rates in the United States have declined in the past two decades, they remain high (Raley & Bumpass, 2003) and the negative effects are clear (e.g., Amato, 2000). While it is unclear whether or not U.S. Army couples are at greater risk of divorce than civilian couples (see Karney & Crown, 2007), the stressors faced by Army couples have increased since 2001 because of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Out of concerns about how increased stress, high operational tempos, and lengthy deployments affect Army families, the U.S. Army Chaplain Corps began ramping up a number of their services aimed at supporting these families. The study described in this brief report examined divorce outcomes following a randomized trial of a couple education program provided by Army chaplains.

Couple education is a promising approach to strengthening marriages. The main goal of such efforts is to teach couples skills, principles, and strategies that increase chances for stable and happy relationships (Markman & Halford, 2005). The reach of these services is becoming greater. For example, The U. S. Administration of Children and Families (ACF) has fielded numerous demonstration projects as well as large randomized intervention trials of such efforts (e.g., Dion, Avellar, Zaveri, & Hershey, 2006). These efforts include large-scale attempts to reach economically-disadvantaged couples with this type of service that is less available to them (e.g., Stanley, Amato, Johnson, & Markman, 2007).

Many evaluations of couple education have been conducted with either premarital or married couples, with encouraging evidence that such strategies could help many couples (Halford, Markman, & Stanley, 2008). In general, most of the studies that have long-term follow-up (one year or longer) focus on couple education with premarital couples and not married couples, but solid evidence exists for the effectiveness of both types of couple education. Studies with follow-ups of one year or longer are especially needed in the evaluation of couple education with married couples.

Regardless of marital status, couple education has been used with both well-functioning, committed couples (often referred to as marital enrichment when given to married couples) or couples who are at high risk or who are already experiencing difficulties (e.g., DeMaria, 2005). Meta-analytic studies provide evidence for positive effects of a diverse range of couple education services (Blanchard, Hawkins, Baldwin, & Fawcett, 2009; Carroll & Doherty, 2003; Hawkins, Blanchard, Baldwin, & Fawcett, 2008). Smaller studies of single samples also provide such evidence (e.g., Bodenmann & Shantinath, 2004; Halford, Sanders, & Behrens, 2001).

Although prior research has consistently demonstrated positive effects of couple education for dimensions such as communication and conflict management, few studies have examined reductions in divorce. This phenomenon could, in part, be due to the fact that very few studies of couple education include long-term follow-ups (e.g., over one year) that would allow for such effects to become evident. To our knowledge, the studies that have documented breakup and/or divorce reduction effects have either been quasi-experimental designs (e.g., Hahlweg, Markman, Thurmaier, Engl, & Eckert, 1998; Markman et al., 1993) or large surveys (Nock et al., 2008; Stanley et al., 2006), all analyzing premarital education in samples that allow for assessment of long-term impacts. These studies all provide evidence of reductions in the likelihood of breakup or divorce resulting from premarital education. To our knowledge, there is no published study from a fully randomized experiment showing evidence on the effects of couple education on relationship stability (divorce) where services were provided to married couples.

The sample used here has a number of strengths for a study in this literature. First, a relatively high percentage of couples include one or both partners who are members of a minority group (40%). Second, given that the sample is comprised of Army couples, it is a relatively lower income sample with modest educational levels compared to many other samples in this literature, allowing for greater generalization of information on effectiveness. Third, the inherent stress of the military context may provide a stronger test of prevention effects than prior studies that have used relatively low-stress couples.

Couple Education within the Army

There has been growing recognition that U.S. Army couples could benefit from relationship support because of the complex ways that military life affects their relationships and how relationships affect the performance of military duties. For example, deployments can place a stress on marriages (McLeland, Sutton, & Schumm, 2008), combat exposure can lead to PTSD which negatively impacts marriages (Allen, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2009), and family problems can affect military functioning and readiness (Schneider & Martin, 1994). Further, it is estimated that 75-85% of suicides in the military are precipitated by relationship loss (Col. Glen Bloomstrom, personal communication, March, 2009). In the mid 1990s, the U.S. Army Chaplain Corps began to systematically train chaplains in variations of the Prevention and Relationship Enhancement Program (PREP; e.g., Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 2001). Along with the increased utilization of variations of PREP, the U.S. Army Chief of Chaplains office funded a study on the effectiveness of these efforts in a research design that included pre, post, and one month follow-up. Results showed that couples participating in PREP delivered by Army chaplains reported gains on many variables (Stanley et al., 2005). However, this research was limited by brief follow-up and the lack of a control group.

The present study reports findings on a fully randomized controlled trial of PREP delivered by Army chaplains, with the hypothesis that, one year following the intervention, those who received PREP would have lower rates of divorce than controls. Hence, this report focuses on the assessment of divorce reduction effects. This is an important research question because it can inform efforts to provide couple education within the military and in other contexts.

Method

Procedures

Approval for all procedures was obtained from our university IRB as well as the U.S. Army IRB (Dwight David Eisenhower Army Medical Center). There were no adverse impacts noted for study participants. All participating couples were recruited from Fort Campbell, KY. To be eligible for the study, couples had to be married, age 18 or over, fluent in English, with at least one spouse in active duty with the Army. Couples could not have already participated in PREP, and they had to express willingness to be randomly assigned to intervention or to an untreated control group, which can be considered treatment as usual. Recruitment was conducted via brochures, media stories, posters, and referrals from chaplains.

Inquires about the study were received from 1102 people. Of those inquiring, 478 couples were contacted, were screened as eligible, were available to participate in the necessary time frames, and participated in the study. Each of these couples was verified to be available for one of 22 iterations of the intervention, often to one led by their unit chaplain. Offering multiple iterations was necessary due to the size of the target sample and to increase the chances for attendance, as the high operational tempo afforded few days off work. Of the 624 couples who inquired but did not participate, reasons for not participating were as follows: did not meet eligibility criteria (n = 93 or 15%), scheduling conflict (n = 65 or 10%), not interested once fully informed (n = 20 or 3%), unable to contact (n = 134 or 21%), no show at pre-assessment (n = 28 or 5%), could not participate because no spots available in upcoming iterations (n = 254 or 41%), and miscellaneous (n = 30 or 5%).

One to 21 days prior to the scheduled iteration, each couple met with research staff at a room provided for study use on the installation. Participants read and signed consent forms before proceeding with pre-assessment (pre). Random assignment occurred immediately after pre-assessment by use of a bag containing a set number of tokens. The number of tokens was determined by the total number of available slots for participant couples in each iteration. For example, if there were 10 slots for iteration 1, the bag for iteration 1 contained 20 tokens: 10 control group tokens and 10 intervention group tokens. After completing pre, each couple blindly drew one token from their iteration’s bag and was assigned to either the intervention or control group. In total, 248 couples were assigned to intervention and 228 were assigned to the control group that participated only in assessments. Two couples dropped out of the study prior to random assignment, leaving 476 couples randomly assigned and analyzed.

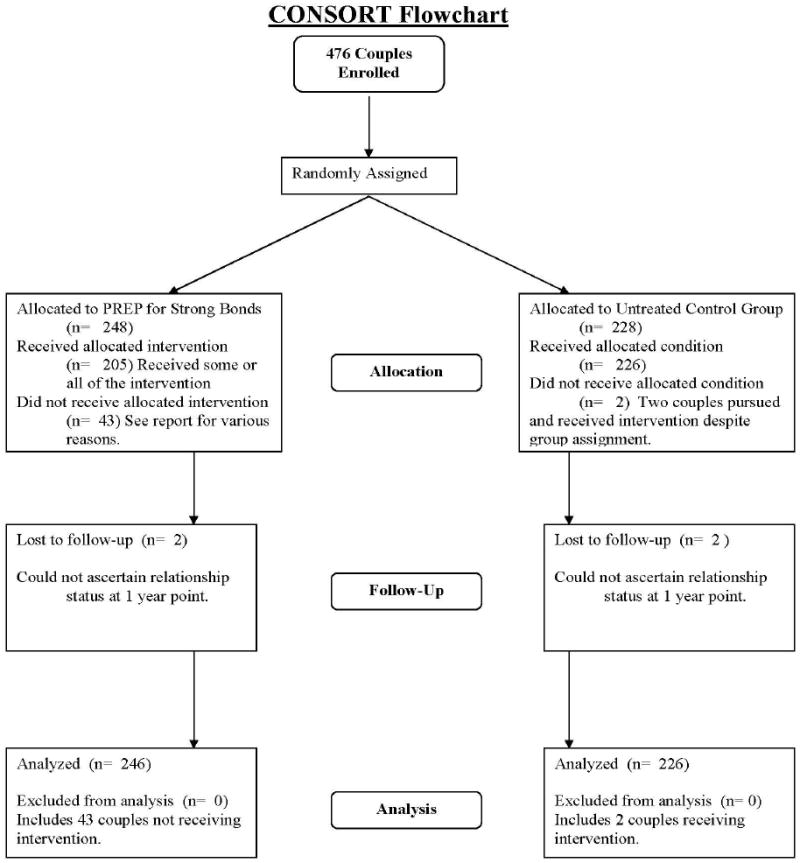

After their iteration was complete, intervention and control couples completed another set of measures for post-assessment (post) under the supervision of study staff. Subsequently, participants completed additional measures at six-month intervals, primarily online. Recruitment, enrollment, and interventions were conducted in 2007. Data collection from Follow-up 2, which is one year post intervention, was completed December 2008. Figure 1 presents the flow chart for this study using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for presentation of randomized trials (Moher, Schulz, & Altman, 2001).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)

Participants

As noted above, 476 couples participated in the current study. At the baseline (pre) assessment, husbands were an average of 27.6 years of age and wives 26.9. Husbands’ modal income (endorsed by 36.7% of men) was between $20,000 and $29,999 a year, while wives’ modal income (endorsed by 69.7% of women) was under $10,000 a year. Seventy-one percent of wives were white non-Hispanic, 11% were Hispanic, 9% African American, 2.5% Native American/Alaska Native, 1% Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 4% endorsed mixed race/ethnicity. Seventy percent of husbands were white non-Hispanic, 12% were Hispanic, 10% African American, 1.5% Native American/Alaska Native, 1% Asian, 1% Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 5% endorsed mixed race/ethnicity. Forty percent of the couples had one or both partners who were members of a minority group. Almost all husbands (97.5%) were Active Duty Army (2.5% were in the study due to the wife being Active Duty Army), whereas almost all wives (91%) were civilian spouses of Active Duty Army males (9% of wives were Active Duty Army or Reserves). High school or an equivalency degree was the modal highest degree (67.8% of the husbands and 59.5% of wives). Couples had been married an average of 4.5 years, and 70% reported at least one child living with them at least part time.

Random assignment does not guarantee groups will be perfectly equal, so we tested whether there were differences between the groups at pre on several variables that could also be associated with divorce. There were no statistically significant differences between intervention and control groups on age, income, education, religiosity, race, number of children, and ethnicity. Similarly, they were not significantly different on the likelihood of the partners being previously married, having a child from a previous relationship, or having lived together prior to marriage. Further, they did not significantly differ in terms of problems with alcohol or drug use. We did find small but significant differences on measures of relationship quality between the two groups of men. Men in the intervention group reported lower marital satisfaction, less confidence in their marriages, and more negative interactions than those in the control condition. These differences and outcomes on these variables will be addressed fully in future reports using these measures. For purposes of this brief report, we note that such differences suggest slightly greater risk for the intervention group prior to intervention, suggesting that the analyses here are a conservative test of the intervention.

Sixty-nine percent of the couples in the sample experienced a deployment in the year prior to pre. The average length of deployment was 12 months. The two groups were not significantly different in the likelihood of deployment in the prior year, nor on length of the most recent deployment before pre. Because the findings presented here are regarding divorce status one year post-intervention, data on deployment during that year are also relevant. We know deployment status through the first six months following post for 88% of the couples. Intervention couples were more likely than control couples to have experienced a deployment within six months of post (43% compared to 33%, χ2 (1) = 4.06, p < .05). However, deployment was not related to divorce in any discernable way. Furthermore, based on all available data, we tested to see if the findings presented here were moderated by deployment history, either prior to pre or subsequent to post. The difference between the intervention and control groups on the likelihood of divorce at the one-year follow-up was always found to be in the same direction as the overall analysis presented below, regardless of deployment.

Intervention

The intervention group received the latest version of PREP as utilized by the Army, called PREP for Strong Bonds (Stanley, Markman, Jenkins, & Blumberg, 2007). Strong Bonds is the name of a broad set of initiatives led by the chaplain corps to strengthen the relationships, marriages, and families of soldiers. PREP for Strong Bonds is an approximately 14-hour psycho-educational, couple education model utilizing the PREP curricula in a group format led by Army Chaplains. PREP for Strong Bonds is designed to teach couples the skills and principles associated with a healthy relationship (e.g., Markman et al., 2001). PREP is an evidence-based couple education program. It (or variants) has been evaluated by numerous different research teams, including studies with long-term follow-ups (5 years). PREP includes many cognitive-behavioral strategies that have been optimized for an educational, preventive model. PREP is usually taught to groups of couples meeting in classes or workshops. Educational strategies include didactic delivery of content, video-recorded demonstrations of negative patterns and skills, group exercises to foster learning and connection among couples, couple practice time, and suggestions for practice outside of meeting time.

The curriculum itself was optimized for use with the U.S. Army by both look (images, graphics, etc.) and content. The workshop structure consisted of two parts: part one was a one-day training occurring on a weekday on post; part two was a weekend retreat at a hotel off post. Modules covered a range of communication and affect management skills, insights into relationship dynamics, principles of commitment, fun and friendship, forgiveness, sensuality, deployment/reintegration issues, and stress management. Chaplains are trained in PREP as part of their preparation to be chaplains. Twenty-seven chaplains provided the training to the couples. Additional briefing regarding PREP for Strong Bonds was conducted by the research team, and 18 of 27 chaplains providing the intervention for this study were able to attend. A detailed manual, including scripts, along with PowerPoint overheads, exercises, and video components, was provided to all chaplains.

Divorce Status

This report focuses on divorce outcomes one year after the post-assessment. Divorce status was assessed using the following question in the standard survey: “Have you and/or your spouse filed for divorce or obtained a divorce?” Couples who answered “no” were coded as not divorced. Almost all (98.1%) couples had at least one member of the couple complete these measures; of the remaining couples, divorce status was ascertained by staff contact with at least one member of the couple. Status for all but four couples was ascertained.

Additional measures were included in the surveys, and will be the subject of future reports, including: relationship quality (e.g., satisfaction, negative interaction, confidence), family functioning (e.g., parenting alliance), mental health functioning (e.g., PTSD, global distress), deployment variables (e.g., types of communication, amount of contact), and Army specific variables (e.g., use of services, exposure to combat).

Results

Data are presented using rigorous intent-to-treat procedures (Hollis & Campbell, 1999); couples were analyzed according to the group they were assigned to, regardless of whether they actually did or did not receive the intervention. In other words, intervention couples who did not receive the intervention were analyzed as if they had and control couples who had received the intervention were treated as if they had not. This method preserves the random assignment of the groups, thereby avoiding selection effects that can impact the interpretation of studies where participants choose or do not choose to participate in an intervention.

Figure 1 shows that two control couples attended the intervention while 43 intervention couples did not attend the intervention. Two control couples attended intervention by independently pursuing this through their chaplain. There were various reasons why 43 couples assigned to intervention did not attend. Some courses were canceled because of a deployment date getting moved up that affected the chaplain leader or the couples planning to attend. At other times, the facility for the course that was lined up became unavailable in order to hold a funeral for a soldier. At the couple level, reasons given included having a child get sick or childcare falling through, duty time for soldier became too intense nearing deployment (the surge occurred during the intervention phase of the study), couples deciding to preserve all available time left before deployment for being together with family, and so forth.

A 2 (intervention vs. control) X 2 (divorced vs. non-divorced) chi-square analysis was used to assess for differences in divorce outcome by assigned group. A chi-square analysis with the Yates correction was used because the cell size for couples in the intervention group who are divorced is five. This chi-square test indicated that the PREP for Strong Bonds group had a significantly lower divorce rate (5/246 = 2.03%) than the control group (14/226 = 6.20%), χ2 (1) = 4.26, p < .05. Fisher’s exact test for significance yielded a value of p = .03.

Discussion

The analysis provides evidence that PREP for Strong Bonds can reduce the risk of divorce for Army couples. The findings suggest that this couple education service provided by Army chaplains had a positive impact on the stability of Army marriages, at least through one year. Couples in the intervention track showed roughly one third the risk of divorce of the control couples. With regard to clinical and practical significance, the findings suggest that approximately 4 out of every 100 intervention couples who would otherwise divorce will not divorce in the year following intervention (4/100 = 6% minus 2%). This difference is based on the intent to treat analyses. A similar analysis based on intervention attendance (all or some versus none) yielded essentially the same result (5.60% divorced for non-treated and 2.00% for treated). One untreated, intervention track couple who divorced shifted from being in the randomly assigned intervention group to being in the untreated group. Future follow-ups are required in order to determine if the results represents a lasting reduction in the risk of divorce. Further, since control group couples may participate in PREP for Strong Bonds (or other Strong Bonds offerings) at some point in the future, it will be necessary to assess services couples in either group have experienced when evaluating long-term outcomes.

The finding of a divorce reduction effect is noteworthy for several reasons. First, this is the first study we know of to document a lower risk for divorce among those receiving best practices couple education in a completely randomized, experimental study. Second, the finding was obtained in one of the largest samples to date. Third, this study extends knowledge about couple education for married couples in a relatively diverse sample of couples with modest incomes. While not a low-income sample, per se, the findings do suggest solid prevention effects for best practices couple education with couples other than those who have substantial financial resources.

We have not included the analysis of marital separations in this report because it has become clear to us that separations mean something very different from divorce in this military sample. In our ongoing tracking of the sample, we have discovered that there are many couples who separate at one point but who reconcile later. Anecdotally, our impression is that a common scenario is discovery of infidelity, marital separation, and, for many, reconciliation over time. Longer-term follow-up is needed to analyze which separations turn into divorces and which turn into reconciliations. Initial separations are equally common in the control and intervention group, yet preliminary trends suggest that couples in the intervention group are more likely to reconcile than control couples. An assessment within 6 months of the one-year follow-up allowed us to identify the current relationship status for 15 of the 25 couples who were separated at the one year point. Among these 15 couples, most intervention couples who had separated had reconciled whereas most control couples who had separated had gone on to file for, or finalize, a divorce. We believe it is premature to make much of this pattern, though it does suggest the potential of an intriguing intervention effect. Separation data will not be fully interpretable until we have collected longer-term follow-up data. We focus on divorce in this report because it is a stable outcome that is readily interpretable.

There are important limitations of this study. First, while the follow-up time period is longer than many studies in this field, the present findings cannot speak to effectiveness over a longer period. It will require longer follow-ups to determine if the present findings are limited to only the one-year point. Second, this study employed a non-treated control group rather than an attention placebo or alternative treatment group. The reason for this is related to the policy question that framed this study: whether or not such services as provided are effective compared to not providing services (similar to the currently ongoing, large federal trials of marriage and couple education in community settings sponsored by Administration for Children and Families). In the absence of such comparison groups, it is not possible to address questions about the relative effectiveness of different interventions and it is likewise not possible to say whether or not effects are due merely to couples receiving increased attention. Third, the findings may only generalize to military couples; while this seems unlikely to us, it remains a matter for future research. Fourth, this study is not able to address which components of couple education interventions are most effective or important. Research addressing such questions would be highly valuable, though such studies will require even larger samples to have the power to detect differences between multiple groups receiving different components of couple education interventions. Finally, analyses of mechanisms of change (mediators) or moderators of program effectiveness (such as prior risk levels) may provide valuable additional information regarding how the program works for various types of couples. Such analyses are planned for the future in this project, and are a very important matter for the field to attend to more broadly.

These findings regarding divorce prevention can help inform ongoing policy discussions concerning the use of couple education in and outside the military. Given the high operational tempo and stress placed on military couples in the U. S. armed services at this time, the present results are encouraging. They suggest the possibility of increasing family stability, at least over the period of one year, for couples who are facing extraordinary challenges. While not without limitations, these findings suggest optimism for the potential of couple education to lower the risk of divorce.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by a grant from The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, awarded to Scott Stanley, Howard Markman, and Elizabeth Allen (R01HD48780). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or NICHD. The first and third authors of this report own a business that develops, refines, and sells the PREP curriculum.

Contributor Information

Scott M. Stanley, Psychology, University of Denver

Elizabeth S. Allen, Psychology, University of Colorado at Denver

Howard J. Markman, Psychology, University of Denver

Galena K. Rhoades, Psychology, University of Denver

Donnella L. Prentice, Center for Marital and Family Studies, University of Denver

References

- Allen E, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Hitting Home: The Effects of Deployment and Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms on Army Marriages. 2009 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1269–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard VL, Hawkins AJ, Baldwin SA, Fawcett EB. Investigating the effects of marriage and relationship education on couples’ communication skills: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:203–214. doi: 10.1037/a0015211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Shantinath SD. The Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET): A new approach to prevention of marital distress based upon stress and coping. Family Relations. 2004;53:477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Doherty WJ. Evaluating the effectiveness of premarital prevention programs: A meta-analytic review of outcome research. Family Relations. 2003;52:105–118. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaria RM. Distressed couples and marriage education. Family Relations. 2005;54:242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Dion MR, Avellar SA, Zaveri HH, Hershey AM. Implementing healthy marriage programs for unmarried couples with children: Early lessons from the Building Strong Families Project. Washington DC: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hahlweg K, Markman HJ, Thurmaier F, Engl J, Eckert V. Prevention of marital distress: Results of a German prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:543–556. [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Markman HJ, Stanley SM. Strengthening couple relationships with education: Social policy and public health perspectives. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:497–505. doi: 10.1037/a0012789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford KW, Sanders MR, Behrens BC. Can Skills Training Prevent Relationship Problems in At-Risk Couples? Four-Year Effects of a Behavioral Relationship Education Program. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:750–768. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AJ, Blanchard VL, Baldwin SA, Fawcett EB. Does marriage and relationship education work? A meta-analytic study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:723–734. doi: 10.1037/a0012584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:670–674. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Crown JS. Families under stress: An assessment of data, theory, and research on marriage and divorce in the military. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Co; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Halford K. International perspectives on couple relationship education. Family Process. 2005;44:139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Renick MJ, Floyd F, Stanley S, Clements M. Preventing marital distress through communication and conflict management training: A four and five year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;62:70–77. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Stanley SM, Blumberg SL. Fighting for your marriage. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McLeland KC, Sutton GW, Schumm WR. Marital satisfaction before and after deployments associated with the global war on terror. Psychological Reports. 2008;103:836–844. doi: 10.2466/pr0.103.3.836-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT Statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Annuls of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:657–662. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock SL, Sanchez LA, Wright JD. Covenant marriage and the movement to reclaim tradition. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Bumpass L. The topography of the divorce plateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research. 2003;8:245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RJ, Martin JA. Military families and combat readiness. In: Jones F, Sparacino L, Wilcox V, Rothberg J, editors. Military Psychiatry: Preparing in Peace for War. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Allen ES, Markman HJ, Saiz CC, Bloomstrom G, Thomas R, Schumm WR, Baily AE. Dissemination and evaluation of marriage education in the Army. Family Process. 2005;44:187–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Amato PR, Johnson CA, Markman HJ. Premarital education, marital quality, and marital stability: Findings from a large, random, household survey. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:117–126. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Jenkins NH, Blumberg SL. PREP for Strong Bonds Leader Manual. Denver: PREP Educational Products, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]