I. Introduction: Some History and Other Vectors

For many years it has been virtually impossible to transfer genes into brain cells either to study or manipulate molecular, cellular, or, in vivo, behavioral processes. In addition to the physical barriers that protect the brain (bone and three layers of meninges), the earliest gene delivery systems, the retroviral vectors, require cell division to integrate the transgenes into their genomes to express any transgenes. Thus they limited transduction to dividing cells of the nervous system, e.g., astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, neurons in the neonatal brain undergoing cell division, or non-neural cells such as fibroblasts that could then be transplanted to the brain. Because neurons in the adult brain do not divide, retroviruses were of limited use to neuro-biologists wanting to manipulate the molecular makeup of neurons in vivo (Fisher and Gage, 1993; Suhr and Gage, 1999; Lowenstein and Castro, 2002; Hsich et al., 2002; see Kageyama et al., this volume, for further discussion).

Far greater transduction efficiencies in the nervous system can now be achieved with the recently developed lentiviral vectors. Lentiviruses are a subclass of retroviruses whose genomes contain additional viral proteins. Two of these virion proteins, matrix (MA) and virion protein R (VPR), are used to transport the cDNA/integrase complex (also called preintegration complex) across the nuclear membrane in the absence of mitosis. This allows lentiviruses not only to infect, but (at least in theory) also to express transgenes in both proliferating, e.g., astrocytes, and nonproliferating cells, such as neurons. In vivo experiments with lentiviral vectors, however, have demonstrated that only neurons express trans-genes, presumably due to a not yet characterized selectivity of lentiviral vectors to infect neuronal cells (Kay et al., 2001; Consiglio et al., 2001; Brooks et al., 2002).

The first lentiviral vectors were derived from human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) but were pseudotyped by using the envelope glycoproteins from other viruses such as the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G), a fusion protein used to improve infection efficiency. The cell line 293 is used to generate these vectors using a three-plasmid cotransfection system. Three separate plasmids encode for the pseudotyped env gene, the transgene cassette, and a packaging construct respectively supplying the structural and regulatory genes in trans (Naldini et al., 1996). Currently other lentivurses, e.g., feline immune deficiency virus and equine infectious anemia virus, have also been engineered as gene transfer vectors. An important attraction of these latter systems is the fact that they are derived from animal, rather than human lentiviruses (Brooks et al., 2002; Curran and Nolan, 2002).

Lentivirus vectors have all the desirable properties of the early Moloney murine leukemia virus (Mo-MLV)-based vectors, but, in addition, can infect both dividing and quiescent cells and induce a limited inflammatory response even in the CNS (Blomer et al., 1997; unpublished observations). Lentiviruses have been used very successfully infecting and transducing the central nervous system (CNS), with almost negligible inflammatory responses (Deglon and Aebischer 2002; Hsich et al., 2002; Tate et al., 2002). Lentiviral vectors are currently being evaluated for safety, with a view to removing all nonessential regulatory genes to facilitate and accelerate approval for clinical trials. If the issues of increased production and safety can be overcome, higher titers are achieved, and public fears of some lentiviral vectors being HIV-1 derived are addressed, these vectors hold great promise for clinical applications within the nervous system (Ailles and Naldini, 2002; De Palma and Naldini, 2002; Galimi and Verma, 2002; Huentelman et al., 2002). Novel and/or improved vector systems are constantly being developed to provide a highly effective technology with which to explore the molecular basis of neuronal gene therapy (see Jakobsson et al., for further discussion).

Having briefly reviewed the current status of vectors available for gene transfer into the brain, we will now explore the potential application of replication-deficient adenovirus vectors as vehicles for gene delivery into the CNS (Table I). A significant feature of adenovirus as a potential vector for DNA delivery in human gene therapy protocols has been that a live (replication-competent) vaccine has been safely administered to many million human beings (U.S. military recruits) over several decades to provide protection against natural adenovirus infections (Rubin and Rorke, 1994). More recently, similar replication-competent adenovirus recombinants encoding defined immunogens have also been used in human vaccine trials, or as replication-competent vectors with or without additional anticancer genes to induce tumor cell killing. Although most adenovirus vaccine development has been based on exploiting replication-competent systems, replication-deficient adenovirus vectors have also proved to be highly effective agents with which to generate both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to expressed transgenes. These vectors have definite attributes as agents for immunization. There is therefore considerable experience in using live adenovirus isolates, replication-competent adenovirus recombinants, and replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus as immunizing agents (Top et al., 1971a, b; Schwartz et al., 1974; Morin et al., 1987; Prevec et al., 1989; Eloit et al., 1990; Jacobs et al., 1992; Gallichan et al., 1993; Rubin, 1994; Wilkinson, 1994a,b; Wilkinson and Borysiewicz, 1995; Amalfitano and Parks, 2002; Nicklin and Baker, 2002; Wickham, 2000).

TABLE I.

A Comparison between Adenovirus Vectors and Other Gene Transfer Methodsa

| Vectors |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ads | HC-Ad | HSV1/r | HSV1/a | AAV | Retro/ lentivirus |

Vaccinia | SFV | Micro injection |

|

| Size (kb) | 36 | 36 | 152 | 5–30 | 4.68 | 7–10 | 185 | 11.51 | 10–30 |

| Cloning capacity (kb) |

7.5 | ~30 | 10–30 | ~150 | 4.5 | 7–10 | 30 | 9–20 | 10–30 |

| Neuronal transduction |

|||||||||

| In vivo? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| In vitro? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Long-term gene expression (≥12 months) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | N/A |

| Gene therapy? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Vaccination | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

HSV-1/r, recombinant HSV1-based vectors; HSV-1/a, amplicon HSV1-based vectors; Ad, adenovirus vectors; HC-Ad, high-capacity, helper-dependent adenovirus vectors; SFV, Semiliki Forest virus vectors.

Furthermore, human gene therapy programs have been launched by a number of groups in the United States and Europe, resulting in the application of replication-deficient adenovirus recombinants in the treatment of patients suffering cystic fibrosis, coronary artery restenosis postpercutaneous angioplasty, brain tumors, head and neck carcinomas, ovarian carcinomas, melanoma, and metabolic disorders among others (Rosenfeld et al., 1992; Engelhardt et al., 1993; Mastrangeli et al., 1993; Simon et al., 1993; Boucher et al., 1994; Bout et al., 1994a,b; Brody et al., 1994a,b; Mittereder et al., 1994; Welsh et al., 1994; Wilson et al., 1994; Yei et al., 1994a,b; Zabner et al., 1994; Kirn et al., 2001; Rutanen et al., 2002; Bauknecht and Meinhold-Heerlein, 2002; Raper et al., 2002). Thus, a wealth of data has accumulated and continues to grow concerning the therapeutic administration of adenovirus and their effectiveness as well as their side effects in human patients.

Interest in exploiting the new capabilities offered by adenoviruses as gene therapy vectors has been very high. The key features that make adenovirus potentially a credible vector for neurological gene therapy specifically are that (1) sufficiently high titers can be easily produced as to allow their administration in vivo, (2) they can transduce many different differentiated cell types, including postmitotic neurons, (3) expression in the target cell can be restricted to the transgene only (reviewed in Legrand et al., 2002; Nicklin and Baker, 2002), and (4) they can be scaled up to very high titres, i.e., 1012–1013 IU/ml. So far adenovirus recombinants have been used to transduce cells of the lung (see above for CFTR transfer; Gilardi et al., 1990; Rosenfeld et al., 1991; Yei et al., 1994a,b), liver (Herz and Gerard, 1993; Ishibashi et al., 1993; Engelhardt et al., 1994; Hayashi et al., 1994; Kozarsky et al., 1994), arteries and other blood vessels (Lemarchand et al., 1992; Roessler et al., 1993; Kingston et al., 2001), joints, bone marrow cells, and various differentiated circulating cells of the immune system (Haddada et al., 1993), heart (Stratford-Perricaudet et al., 1992; Kass-Eisler et al., 1993), skeletal muscle (Quantin et al., 1992; Stratford-Perricaudet et al., 1990, 1992; Acsadi et al., 1994a,b), brain (Akli et al., 1993; Bajocchi et al., 1993; Davidson et al., 1993; Le Gal La Salle et al., 1993; Ambar et al., 1999; Dewey et al., 1999; Thomas et al., 2000a,b, 2001a,b), and spinal cord (Lisovoski et al., 1994), and to release factor IX into the bloodstream (Smith et al., 1993). The widespread potential applications of adenovirus systems has promoted further developments of the adenovirus vectors, in particular, efficient strategies have been devised for the insertion of transgenes into recombinant adenovirus. Also, the further developments have concentrated on two main limitations of the adenoviral vectors, namely, the limited transgene capacity of first-generation adenoviral vectors and the inflammatory and immune responses caused by the adenoviral virions and its genome. Inserts of up to 8 kbp are feasible in replication-deficient recombinants, which can be grown without helper virus on trans-complementing 293 cells (Graham et al., 1977; Berkner, 1988; Wilkinson, 1994a,b), gutless vectors, and the new helper-dependent high-capacity vectors have a theoretical capacity of up to 30–36 kbp (Lowenstein et al., 2002; Hartigan-O’Connor et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2002).

Recent reviews have provided detailed protocols and methodologies involved in constructing and utilizing adenovirus vectors for gene transfer to cells of the brain both in vitro and in vivo (Lowenstein, 1995; Southgate et al., 2001; Thomas et al., 2001a,b; see Phillips, 2002). In this chapter, we will consequently concentrate on progress that has been made in the application of such vectors within the context for their exploitation for neurobiology and discuss potential future developments in this field.

II. The Vector System

Adenoviruses have the ability to infect a wide range of different tissues and cell types. It has been shown convincingly that adenovirus type 5 serotype initiates infection by binding to the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) through the knob domain located at the distal extreme of the fiber protein (Bergelson et al., 1997; Roelvink et al., 1999). CAR is a 46-kDa integral membrane protein with a typical transmembrane region and an extracellular region composed of two immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains (Tomko et al., 1997). The C-terminal knob of the fiber protein confers the specificity of the cellular receptor recognition. Following its binding to CAR, adenovirus is subsequently internalized through an interaction with integrins on the cell surface of the target cells, especially αvβ5 (Wickham et al., 1993). Entry into the cell is by receptor-mediated endocytosis (Wickham et al., 1994), after which the viral nucleocapsid is released from endosomes into the cytoplasm, and transported to the nucleus (Greber et al., 1993; Trotman et al., 2001). The double-stranded DNA genome (~36 kb; Fig. 1) is then released into the nucleus of the infected cell (Trotman et al., 2001). Upon infection of a permissive cell, the replication cycle can be divided into three phases of gene expression: immediate early (E1 genes), early (E1–E4 genes), and finally the late events, which follow the onset of viral DNA replication. The very first region of the genome to become active is the left-hand region of the left strand, E1, which encodes a series of transcriptional activators, which will promote progression into the early phase of gene expression. These phases of virus replication are associated with host cell cycle progression to S1, onset of viral DNA replication, as well as the production of gene products associated with evasion of host antivirus defenses. Five late transcriptionally active regions are found at the right of the left strand, and are produced from a single major late promoter by alternative splicing (L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5). Expression of late viral genes becomes activated after the start of viral DNA replication and will eventually lead to the assembly of progeny virions, in excess of 105 new virions per infected cell (Shenk, 1995).

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic representation of an adenovirus particle based on the current understanding of its polypeptide constituents and genome. (B) Genome is 100 map units (mu) in length (1 mu = 360 bp). Early primary mRNA transcripts are designated in bold. Certain polypeptides are identified by conventional numbering system (roman numerals). Modified from Flint et al. (2000). (See Color Insert.)

Most available recombinant adenoviruses for use as vectors for gene transfer are rendered replication defective through deletions in the E1, E2, E3, or E4 regions, or through combinations thereof. These vectors, have been termed “first (and sometimes second and third)-generation” adenovirus vectors, depending on the authors, and the particular deletions to increase the cloning capacity (Gilardi et al., 1990; Davidson et al., 1993; Brody et al., 1994b; Wilkinson, 1994a,b; see Philips, 2002). The regions deleted comprise some genes that are necessary for replication (e.g., those located in the E2 region), to others that do not appear to be necessary for replication (e.g., the E3 and E4 region) and that encode genes associated with modulating the host immune response and transcriptional control. No deletions are neutral, and they will have varying effects on the production, replication, expression, and toxicity of the particular viral vectors. Replication-deficient adenovirus recombinants deleted in various genes or genomic regions are commonly grown on trans-complementing 293 cells that express an integrated copy of the Ad5 E1 gene, complemented by other regions in the case of deletions in the E2 region (Graham et al., 1977). Transcomplementation with the E3 or E4 region has usually not been necessary.

Efficient systems to construct adenovirus recombinants are now available both from a number of different laboratories, and more recently also from various commercial sources (e.g., Microbix Biosystems Inc., Toronto, Canada; QBio Gene, Montreal, Canada). These allow the construction of both replication-competent and replication-deficient recombinant adenoviruses for gene transfer (Prevec et al., 1989), using conventional and well-established DNA cloning and transfection procedures (Sambrook, 1989). Most published reports utilize adenovirus (Ad) recombinant derived from either serotypes 5 or 2 (see Table II), although there are some 47 human serotypes identified and many more animal isolates, some of which have also been used within the context of gene transfer (Cotten et al., 1993). The exploration of other adenoviral serotypes has substantially increased since 1995 as some of their distinct properties concerning the receptors used for entry, the consequent cell types transduced, have been discovered to differ in important ways from adenovirus type 2 and 5 (Zabner et al., 1999; Segerman et al., 2000; Shayakhmetov et al., 2000). In Ad E1-deleted vectors, transgenes are usually inserted into the E1 region under the control of exogenous viral promoters (e.g., RSV-LTR, IE-hCMV). Cell specific alone, or combined with inducible promoters, or other elements that increase expression levels can also be used effectively to target expression to specific cell types, to regulate its expression, and to increase expression levels (Babiss et al., 1986; Bessereau et al., 1994; Grubb et al., 1994; Smith-Arica et al., 2000, 2001; Southgate et al., 2001; Gerdes et al., 2000; Harding et al., 1998; Ralph et al., 2000; Glover et al., 2002). Most recently the use of replication-competent adenoviruses for the treatment of turmors has also begun to be explored (Nanda et al., 2001; Doronin et al., 2000, 2001).

TABLE II.

Review of Publications Using Recombinant Adenovirus Vectors for Gene Transfer into the Brain or Constituent Cells

| Referencesa | Recombinant adenovirus E1 vector |

Target in vitro and in vivo |

Therapeutic efficacy/type of experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) “Early” Adenoviral Gene Transfer into the Brain (1993–1994) | |||

| Akli et al. (1993) | Ad-RSVlacZ, Ad type 5 | Brain in vivo; rats | Gene transfer into the rodent brain in vivo |

| Bajocchi et al. (1993) | Ad-RSVlacZ, Ad-α1AT, Ad type 5 |

Intraventricular or intrastriatal administration; 5 × 108–109 pfu/animal |

Gene transfer of marker enzymes and transgenes into the rodent ventricles and brain in vivo |

| Bennett et al. (1994) | Ad-CMVlacZ; Ad5 | Adult mouse mammalian retina; subretinal injection of 102–109 pfu/retina in 1–10 μl |

Gene transfer into retina in vivo |

| Caillaud et al. (1993) | Ad-RSVlacZ; Ad5 | Primary cultures of neurons and glial cells |

Gene transfer into neural cells in vitro |

| Davidson et al. (1993) | Ad-CMVlacZ Ad type 5 E1; E3 | In vivo: intrastriatal, mice | Gene transfer into rodent brain in vivo |

| Jomary et al. (1994) | Ad2/CMV lacZ | Retinal cells | Gene transfer of marker cells into retina |

| Le Gal La Salle et al. (1993) | Ad-RSVlacZ, Ad type 5 | SCG and astrocytes in culture. Hippocampus and substantia nigra (SN) in vivo: 3–5×107 pfu/injection |

Gene transfer into brain cells in vivo and in vitro |

| Li et al. (1994) | Ad-CMV β-Actin-nls lacZ; Ad5 | Subretinal injection in normal and mutant mice of 4 × 104–4 × 107 pfu in 0.3–0.5 μl/retina |

Gene transfer into retina in vivo |

| Ridoux et al. (1994b) | Ad-RSVlacZ | Astrocytes in vitro; 2 × 107 pfu/confluent dish |

Gene transfer into astrocytes prior to intracranial transplantation |

| (2) Ex Vivo Gene Transfer and Transplantation of Transduced Cells | |||

| Hughes et al. (2002) | Ad-lacZ or eGFP |

In vitro: embryonic murine neural progenitor cells |

FIV-transduced progenitors retain potential for differentiation; Ad induces differentiation into astrocytes |

| Corti et al. (1999) | Ad-tet-TH | In vitro: human neural progenitor cells | Ad encoding TH under negative control of the tetracycline regulatory system produces high levels of TH in neural progenitor cells |

| Boer et al. (1997) | Ad-lacZ | In vivo: third ventricle of rats |

Ex vivo Ad delivered transgene expression of neurografts implanted in the third ventricle is compared to explant cultures |

| Yoon et al. (1996) | Ad-lacZ or p75 | In vivo: intraventricular injection in mice | Ad-mediated reporter genes are intro- duced into progenitor cells to monitor their migration and assess stability of transgene expression |

| (3) Recent Vector Developments | |||

| Umana et al. (2001) | HD-Ad-lacZ | In vivo: rats | Use of FLPe recombinase to improve quality and quantitiy of HD Ad production |

| Xia et al. (2000) | Ad-GFP, Ad5GFPBxHI, where “x” is the epitope number |

In vitro: engineered cell lines and human brain microcapillary endothelia |

The Ad HI loop is modified to achieve binding to a specific receptor; this is used to achieve a disseminated pattern of transduction |

| Cregan et al. (2000) | HD-Ad-lacZ |

In vitro: primary cerebellar neuronal cultures |

Efficacy and cytotoxicity of an HD Ad is compared to a first-generation Ad |

| Zheng et al. (2000) | Chimaeric Ad-retroviral vector |

In vitro: in vivo: submandibular gland, cortex, and caudate nucleus |

Examination of the characteristics of an Ad construct containing LTR sequences of a retroviral vector |

| Beer et al. (1998) | Encapsulated RAds | In vitro; in vivo: mice | Administration of PLGA encapsulated Ad to diminish immunogenicity of the viral vectors |

| Sato et al. (1998) | Ad-bc12; regulatable by cre |

In vitro: PC12, a hybrid motoneuronal cell line and primary chicken motoneurons |

A new strategy for delivery of Bcl-2 mediated by Cre/loxP recombination using Ad vectors |

| Peltekian et al. (2002) | CAV2 | In vivo: rat | Selective transduction of neuronal cells by CAV2 vectors introduced as a new tool for targeting key structures of neurodegeneration |

| Soudais et al. (2001) | CAV2 | Rodent CNS neurons in vitro, and in vivo | Neurotropism of CAV2 and its efficient retrograde transport are demonstrated |

| (4) Transcriptional Targeting | |||

| Kugler et al. (2001) | Ad-NSE, tubulin α1, synapsin promoters-lacZ or Bcl-X(L) |

In vitro: primary neuronal cultures; in vivo: rats |

Different cellular promoters are investi- gated in an adenoviral context to determine their capability of neuron- restrictive transgene expression |

| Smith et al. (2000) | Ad-CMV, RSV, E1A promoters-lacZ or eGFP |

In vitro: hippocampal brain slices; in vivo: rat hippocampus |

Cytotoxicity and transgene expression from three viral promoters in the same Ad backbone are compared |

| Ralph et al. (2000) | Ad-synapsin 1, GFAP-tet-eGFP |

In vitro: primary hippocampal cultures; in vivo: rat hippocampus |

Ad system employing regulatable, cell-specific transgene expression |

|

Navarro et al. (1999); Nillecamps (1999) |

Ad-NSE, RSV promoters-LacZ | In vivo: rat | NSE and RSV promoters driving LacZ in an Ad are compared |

| Ad-xNRSE-PK-luc, x denotes ≤ 12 NRSE elements |

In vitro: different nonneuronal and neuronal cell lines and primary SCG neurons; in vivo: mouse tongue injection, rats |

More specific neuronal transgene expres- sion is achieved with an Ad vector construct encoding luciferase with in- creasing numbers of NRSEs upstream of the phosphoglycerate promoter |

|

| Miyaguchi et al. (1999) | Ad-SCG10-NRSE-lacZ | In vitro: rat hippocampal slice cultures | NRSE in an Ad-encoding LacZ to achieve selective neuronal expression |

| Smith-Arica et al. (2000) | Ad-tet-GFAP, NSE, β-Actin- CMV promoters |

In vitro: different cell lines and primary neocortical cultures; in vitro: rats |

A dual Ad system encoding for cell-type- specific and regulatable transcription units is tested |

| Morelli et al. (1999) | Ad-NSE, GFAP, hCMV promoters—FasL |

In vitro: primary, neuronal, glial, fibroblastic, and epithelial cell lines; in vivo: systemic administration in mice |

Ads encoding FasL controlled by non- specific and cell-type specific promo- ters are tested in different cell types and in vivo |

| Shering et al. (1997) | Ad, HSV-1, HSV-1 amplicon vectors—hCMV |

In vitro: rat nervous system cell cultures | Cell-specific expression from a short HCMV major IE promoter enhancer is assessed in Ad and HSV-1 viral vectors |

| (5) Targeting through the Blood–Brain Barrier | |||

| Nilaver et al. (1995) | Ad-RSVlacZ, HSV-1-lacZ |

In vivo: intracerebral xenografts of human LX-1 small cell lung carcinoma in nude rats |

Distribution of LacZ delivered by Ad and HSV-1 vectors after intratumor or intracarotid administration +/− osmotic disruption of the BBB |

| Muldoon et al. (1995) | Ad, HSV | In vivo: rat and cat | Delivery of Ad, HSV, and MION into normal brain or intraarterially is compared in animals with intact or disrupted BBB |

| Doran et al. (1995) | Ad-lacZ | In vivo: rats | Short-term gene expression is evaluated after intracarotid administration of an Ad encoding lacZ after or without osmotic BBB disruption |

| (6) Brain Immunity/Inflammation | |||

| Zermansky et al. (2001) | Ad-HSV1-TK | In vivo: rats | 12 months persisting high-level and widespread expression of Ad delivered HSV1-TK is transgene dependent |

| Thomas et al. (2001a) | Ad-hCMV-lacZ or HPRT | In vivo: rats | Mechanisms contributing to the decline in transgene expression delivered by first generation Ad vectors are examined |

| Thomas et al. (2002) | Ad-hCMV-lacZ, luc with different capsid modifications |

In vivo: rats | Engineered viral capsids ablated for CAR and/or integrin and their in- flammatory potential are examined |

| Thomas et al. (2001b) | Ad-hCMV-lacZ or HPRT, HD-Ad-hCMV-lacZ |

In vivo: rats | Effects of preexisting antiadenoviral im- munity on transduction of brain cells with HD Ad and first-generation Ad are compared |

| Zou et al. (2001) | Ad-lacZ, HD-Ad-lacZ |

In vivo: intraventricular and intrahippocampal administration in rats |

Toxicity and immunogenicity of HD and first-generation Ad vectors and their effect on transgene expression are compared |

| Cua et al. (2001) | Ad-IL10 |

In vivo: animal model of autoimmune encephalomyelitis |

Therapeutic effects of intracranial and systemic administration of an Ad encoding an antiinflammatory cyto- kine are compared |

| Gerdes et al. (2000) | Ad-hCMV, mCMV promoters- lacZ |

In vivo: rats | Ad-delivered MIEmCMV promoter per- formance is characterized |

| Driesse et al. (2000) | Ad-TK or lacZ | In vivo: rats and nonhuman primates | Analysis of immune response to CSF administration of Ad encoding TK with subsequent GCV or lacZ |

| Zou et al. (2000) | Ad and HD-Ad-β-Geo | In vivo: hippocampus of rats | Immunogenicity and its effects on trans- gene expression and stability are com- pared in HD and first-generation Ad |

| Kajiwara et al. (2000) | Ad-lacZ | In vivo: mice | Investigation of the humoral immune response to a first-generation Ad and its transgene delivered into the brain |

| Dewey et al. (1999) | Ad-TK | In vivo: rat glioma model | Characterization of long-term effects of Ad-mediated conditional cytotoxic gene therapy for glioma |

| Ohmoto et al. (1999) | Ad-lacZ | In vivo: different mouse strains | Influence of environmental conditions and animal priming with Ad on quality and duration of immune response to Ad gene delivery is examined |

| Cartmell et al. (1999) | Ad-hCMV-lacZ, Ad-0, Ad-TK |

In vivo: intrastriatal and intraventricular administration in rats |

Role of TNF-α and IL-β in mediating an early inflammatory response to Ad administered to different CNS targets is delineated |

| Proescholdt et al. (1999) | Ad-CMV-VEGF, Ad-CMV-lacZ | In vivo | Inflammatory response to Ad-mediated VEGF versus pump-injected protein and its effects on the integrity of the BBB are studied |

| Shine et al. (1997) | Ad-RSV-TK | In vivo: cotton rat | Toxicity of Ad-mediated TK +/− GCV at different doses in naive and pre- immunized rats is tested |

| Kajiwara et al. (1997) | Ad-lacZ | In vivo: mice | Quantitative analysis of the immune response to an Ad-encoding lacZ and transgene longevity |

| Byrnes et al. (1996) | Ad-lacZ | In vivo: mice | Immune response to Ad-delivered lacZ is examined |

| Byrnes et al. (1996a) | Ad-RSV-lacZ, HSV-1 RSV- lacZ, HSV-1 tsK |

In vivo: caudate nucleus of rats | Duration of Ad-mediated transgene ex- pression and related inflammation in immune-naive animals and subse- quent peripheral exposure to the vector are compared |

| Byrnes et al. (1995) | AdR1, Ad0, Ad5 | Brain, in vivo; 3 × 106 pfu/0.5 μl, injection site |

Study of the immune response to the direct administration of adenovirus recombinants into the brain. |

| Davidson et al. (1994) | Ad5-RSV-lacZ and RSV-rHPRT | Striatum and cortex in vivo | Gene therapy into primate brain; im- mune response to adenovirus vectors and encoded transgenes |

| (7) Neuroprotection | |||

| Wang et al. (2001) | Ad-WldS | In vitro: rat DRG neurons | Ad-mediated WldS protein utilized against axonal degeneration |

| Tominaga-Yoshino et al. (2001) | Ad-APP, Ad-lacZ | In vitro: cultured hippocampal neurons | Adenoviral introduction of APP cDNA to enhance neurotoxic and neuro- protective effects of glutamate |

| Yuan et al. (1999) | Ad-CMV-APP or lacZ | In vitro: central neuron cultures | Ad is used as a vector for protein trafficking and processing studies to elucidate pathogenesis of AD |

| Horellou et al. (1994) | Ad-RSV-hTH, Ad-RSVlacZ | Brain in vivo | Gene therapy of Parkinson’s disease; significant reduction in abnormal behavior of intrastriatal AdRSVhTH vs AdRSVlacZ |

| Apoptosis Zhu et al. (2002) |

Ad-TGF-β1 | In vivo: mouse brains | Transfer of an antiapoptotic gene to the CNS for neuroprotection |

| In vitro: rat primary hippocampal cells | |||

| Araki et al. (2001) | Ad-(wt or mutant) PS2, Ad-lac | In vitro: rat primary cortical neurons | The proapoptotic effect of Ad-mediated PS2 overexpression is examined in vitro |

| Xia et al. (2001) | Ad-EGFP, Ad-JBD |

In vitro: human neuroblastoma cells; in vivo: mouse MPTP model of PD |

Ad-induced inhibition of the JNK path- way protects MPTP lesioned DA neurons |

| Neurotrophic factors Dorsey et al. (2002) |

Ad-trkB |

In vitro: cultured primary hippocampal neurons |

Correction of dysregulated receptor expression with an adenoviral vector relating to an animal model of Down’s syndrome |

| Benraiss et al. (2001) | AdCMV-BDNF-IRES-hGFP |

In vivo: intraventricular administration in rats |

Ad delivered BDNF to induce neuronal recruitment from endogenous progeni- tor cells in the adult forebrain |

| Connor et al. (2001) | Ad-lacZ, Ad-GDNF |

In vivo: intrastriatal and intra-SN administration in a 6-OHDA rat model of PD |

Neuroprotective mechanisms of Ad- mediated GDNF are elucidated |

| Kozlowski et al. (2001) | Ad-hGDNF | In vivo: monkey caudate nucleus | Quantitative assessment of Ad-mediated hGDNF expression, using ELISA and (RT-)PCR techniques |

| Kozlowski et al. (2000) | Ad-lacZ, Ad-GDNF |

In vivo: intrastriatal and SN injection in a 6-OHDA rat model |

Behavioral testing of Ad-mediated GDNF therapy into the striatum or SN is compared |

| Connor et al. (1999) | Ad-LacZ, Ad-GDNF, Ad-mu GDNF |

In vivo: 6-OHDA PD model in aged rats | Effects of Ad-mediated GDNF delivery to the striatum and SN are compared |

| Kitagawa et al. (1999) | Ad-LacZ, Ad-GDNF | In vivo: rats | Effects of Ad-mediated GDNF on is- chemic brain injury are studied |

| Bemelmans et al. (1999) | Ad-LacZ, Ad-BDNF | In vivo: rat model of Huntington’s disease | Therapeutic value of an intrastriatal injection of Ad-mediated BDNF in Huntington’s disease is assessed |

| Choi-Lundberg et al. (1998) | Ad-lacZ, Ad-mGDNF, Ad-GDNF |

In vivo: intrastriatal injection in 6-OHDA rat model of PD |

Effects of intrastriatal administration of an Ad encoding GDNF on dopami- nergic cell survival are examined |

| Choi-Lundberg et al. (1997) | Ad-lacZ, Ad-mGDNF, Ad-GDNF | In vivo: 6-OHDA rat model of PD | Neuroprotective effect of Ad-mediated GDNF injected near the SN is exam- ined |

| (8) Traumatic or Ischemic Brain Injury/Excitotoxicity | |||

| Qiu et al. (2002) | Ad-FasL |

In vivo: mouse parietal cortex and contused human cortical tissue samples |

Role of Fas receptor in traumatic brain injury is addressed with an Ad encod- ing FasL |

| In vitro: embryonal cortical neurons | |||

| Kim et al. (2002) | Ad-Cu/Zn SOD | In vivo: rats | Intracisternal administration of an Ad encoding human Cu/Zn SOD to restore CBF autoregulation after fluid percussion injury |

| Matsuoka et al. (2002) | Ad-bFGF, Ad-Bcl-xL | In vitro: rat neuronal cells | Synergistic neuroprotective effect through Ad-mediated bFGF and Bcl- xl against EAA toxicity |

| Aoki et al. (2001) | Ad-GRP78 |

In vitro: rat hippocampal neurons; in vivo: hippocampus of gerbils |

Ad-mediated overexpression of GRP78 preserves rat neurons; hypothermic treatment is neuroprotective by restor- ing GRP78 expression in ischemic brain |

| Masada et al. (2001) | Ad.RSVlacZ, Ad-IL-1ra |

In vivo: cerebral intraventric-ular injection in rats |

Ad-mediated overexpression of IL-1ra reduces ischemic brain injury |

| Yang et al. (2001) | Ad-CMV-lacZ, Ad-CMV- mSAG, Ad-CMV-SAG |

In vivo: mouse | Overexpression of SAG, an antioxidant protein, via an Ad vector to prevent ischemic injury of brain cells |

| Gupta et al. (2001) | Ad-RSV-LacZ, Ad-RSV-GT | In vitro: hippocampal cultures | Ad-induced overexpression of the Glut-1 glucose transporter in vitro enhances neuronal survival after exposure to the excitotoxin KA |

| Ralph et al. (2001) | Ad-TRE-pep2m, Ad-TRE- pep4c, Ad-TRE-EGFP, Ad-Syn-tTA |

In vitro: primary hippocampal neurons | AMPA receptors convey postischemic neurotoxicity; Ad-mediated reduction of AMPA receptor expression provides neuroprotection |

| Ooboshi et al. (2001) | Ad-lacZ | In vivo: spontaneously hypertensive rats | Effects of brain ischemia on expression of an Ad-delivered marker gene are examined |

| Yang et al. (1999) | Ad-RSV-lacZ, AdRSV-IL-1ra | In vivo: CD-1 mouse | Ad-mediated overexpression of IL-1ra is used to assess the role of interleukin-1 in cerebral ischemia |

| Yang et al. (1999) | Ad-RSV-lacZ, AdRSV-IL-1ra |

In vivo: intraventricular administration in CD-1 mice |

Effects of Ad-delivered IL-1ra on ICAM- 1 protein in cerebral ischemia |

| Yang et al. (1997) | Ad-RSV-lacZ, AdRSV-IL-1ra |

In vivo: intraventricular administration in mice |

Effect of Ad-mediated IL-1ra on cerebral ischemia is assessed |

| Hagan et al. (1996) | Ad-lacZ, Ad-IL-1ra | In vivo: perinatal rats | Impact of Ad-mediated overexpression of IL-1ra is assessed in a model of excitotoxicity |

| Betz et al. (1995) | Ad-RSV-lacZ, AdRSV-IL-1ra | In vivo: intraventricular injection in rats | Suitability of Ad-mediated IL-1ra in reducing ischemic brain damage is tested |

| (9) Brain Tumors | |||

| Abe et al. (2002) | Ad-lacZ, Ad-p53 | In vivo: athymic rat brains | Intraarterial infusion of p53-containing Ad |

| Shinoura et al. (2002) | Ad-APAF1, Ad-Casp9, Ad-Bax, Ad-Fas, Ad-p53 |

In vivo: glioma cells harboring a mutated p53 |

Cotransduction of Apaf-1 and caspase-9 via Ad to increase p53-mediated apoptosis in glioma cells |

| Miller et al. (2002) | Ad-CMV-CD |

In vitro: different human tumor cell lines; in vivo: immunodeficient mouse model of glioma |

Glioma cell lines can be as sensitive as GI tumor cells to the antineoplastic effects of 5-FU; efficacy and specificity of Ad- mediated CD and subsequent systemi- cally delivered 5-FC are tested in a mouse model of human glioma |

| Adachi et al. (2002) | Ad-uPAR/p16 |

Ex vivo intracerebral tumor model and in vivo subcutaneous tumor model |

Ad-mediated delivery of a bicistronic construct containing antisense uPAR and sense p16 genes to suppress glioma invasion and growth |

| Nanda et al. (2001) | IG.Ad5E1(+); E3Luc, HSV1- TK gene [IG.Ad5E1(+).E3TK] |

In vitro: human glioma cell lines, rat gliosarcoma cell line, other tumor cell lines; in vivo: a mouse s.c. glioma xenograft model |

Combination of replication-competent Ad and the HSV1-TK/GCV suicide system to improve glioma treatment outcome |

| Maleniak et al. (2001) | AdhCMV-mFasL, Ad-CMV-TK |

In vitro: primary human glioma-derived cell cultures |

Ad delivered FasL or HSV1-TK/GCV therapy to induce cell death in some glioma cell lines resistant to the chemotherapeutic agent CCNU |

| Okada et al. (2001) | Ad-TK | In vivo: rat glioma model | s.c. tumor injection of Ad expressing HSV1-TK/GCV shows vaccination effect by inducing a CTL response |

| Galanis et al. (2001) | Ad-MV-F/H |

In vitro: cultured glioma cell lines; in vivo: glioma xenografts in nude mice |

Assessment of two fusogenic membrane glycoproteins as adenovirally delivered transgenes for glioma therapy |

| Lammering et al. (2001) | Ad-EGFR-CD533 |

In vitro: human glioma cell lines; in vivo: glioma xenografts |

Ad-mediated overexpression of a dominant- negative epidermal growth factor receptor to achieve radiosensitization of glioma cells |

| Glaser et al. (2001) | Ad-TK | Human malignant glioma cells | Molecular pathways mediating TK/ GCV-induced cell death are eluci- dated |

| Eck et al. (2001) | Ad-CMV-hIFN-β | Phase I trial in humans | Assessment of toxicity and efficacy of hIFN-β intralesional gene therapy for patients with recurrent or progressive malignant glioma with tumor resection |

| Sandmair et al. (2000) | Ad-CMV-TK | Phase I trial in humans | Evaluation of safety and efficacy of TK gene therapy by using retrovirus packaging cells and Ad |

| Trask et al. (2000) | Ad-RSV-TK | Phase I clinical study | Patients with recurrent malignant brain tumors are treated with HSV TK/ GCV |

| Lawinger et al. (2000) | Ad-REST-VP16 |

In vitro: three types of human medulloblastoma cells |

Effects of expression of REST-VP16 mediated by an Ad vector are studied in medulloblastoma cells |

| Brust et al. (2000) | Ad-TK |

In vitro: RT2 rat glioma cells; in vivo: soft tissue RT2 cell tumors in rats |

Combination of Ad-delivered TK/GCV therapy and subsequent radiosensitiza- tion with BrdC |

| Shinoura et al. (2000) | Ad-FasL, Ad-p53 |

In vitro: A-172 and U251 glioma cell lines |

Coinfection with Ad-mediated p53 and FasL to enhance apoptosis in glioma cells |

| Kurihara et al. (2000) | AxCALNLNZK, Ax2iNPNCre |

In vitro: seven human glioma cell lines, HeLa and COS-7 cells |

Glioma-cell specific Ad-mediated expres- sion is compared in different glioma and nonglioma cell lines |

| Cowsill et al. (2000) | Ad-TK, AdΔTK |

In vitro: primary neuronal and glial cultures; in vitro: rat striatum |

Ad encoding TK or its truncated form +/− GCV is compared |

| Adachi et al. (2000) | Ad-lacZ, Ad-CAG-UPRT, Ad-CD | In vivo: rat brain tumor model | Ad-mediated combined CD/5-FC and UPRT therapy is evaluated |

| Fathallah-Shaykh et al. (2000) | Ad-lacZ, AdIFNγ |

In vivo: mouse model of metastatic brain tumor |

Therapeutic effect of Ad-mediated IFN- γ is examined |

| Biroccio et al. (1999) | Ad-p53, Ad-0 | In vitro: different glioblastoma cell lines | wt-p53 gene transfer enhances BCNU sensitivity in glioblastoma cells depen- ding on the administration sequence |

| Harada et al. (1999) | Ad-p16 | Evaluation of the effect of restoring Ad- mediated p16 on tumor angiogenesis in p16-deleted glioma cells |

|

| Shinoura et al. (1999) | Adv-lacZ-F/K20 and Adv-lacZ-F/wt |

In vitro U-373 MG glioma cells; in vivo | Therapeutic effect of replication- competent Ad with a fiber mutation is compared to its corresponding Ad with wt fiber |

| Wagenknech et al. (1999) | Ad-XIAP | In vitro: different human glioma cell lines | Expression and biological activity of XIAP in human malignant glioma are examined using Ad as a delivery tool |

| Driesse et al. (1998) | Ad-TK | In vivo: nonhuman primates | Toxicity study of Ad-mediated TK with GCV therapy |

| Puumalainen et al. (1998) | Ad-lacZ, BAG retrovirus-lacZ | In vivo: humans | Safety and efficiency of retrovirus and Ad-mediated β-galactosidase in human malignant glioma are examined |

| Gomez-Manzano et al. (1997) | Ad-p53/p21 | In vitro: human glioma cell lines | Ad-mediated p53 and p21 is examined to characterize their role and timing in p53-induced apoptosis |

| Smith et al. (1997) | Ad-GFP, Ad-GFP/5-HT3 | In vivo: rats and monkeys | Toxicity and dose profiles are presented for Ad-mediated TK and systemic GCV administration in healthy animals |

| Tanaka et al. (1997) | Ad-sPF4 | RT2 glioma cells in vitro and in vivo, injected into the subrenal capsule or the caudate nucleus of nude mice |

Analysis of the activity of retroviral and Ad vectors expressing a secretable form of PF4, an antiangiogenic protein |

| Eck et al. (1996) | Ad-TK |

In vivo: human phase I trial in patients with recurrent glioma |

Evaluation of safety and efficiency of Ad-mediated TK followed by systemic GCV therapy |

| Vincent et al. (1996a) | Ad-MLP-luc, Ad-MLP-TK |

In vitro: several human cell lines; in vivo: rats |

Efficiency of Ad-mediated TK and systemic GCV administration is as- sessedin a rat model of leptomenin- geal metastases |

| Goodman et al. (1996) | Ad-RSV-TK | In vivo: baboons | Toxicity studies of Ad-mediated TK and systemic GCV in nonhuman primates |

| Vincent et al. (1996b) | Ad-TK | In vivo: 9L tumors in rats | Ad-mediated TK transfer is compared to retroviral mediation followed by sys- temic GCV in a rat gliosarcoma model |

| Viola et al. (1995) | Ad-lacZ |

In vitro: human glioma cell cultures; in vivo: rat models of solid brain tumors and meningeal cancer |

Transduction profiles of Ad encoding β-galactosidase in solid and leptomi- nengeal tumor models are assessed |

| Badie et al. (1994) | AdLacZ | Rat C6 glioma cells | Delivery of marker genes to the CNS and brain tumors |

| Boviatsis et al. (1994) | Ad5MLP lacZ | Rat 9L gliosarcoma cells |

β-Galactosidase expression in tumors and neurons; tumor necrosis |

| Chen et al. (1994) | Ad5, Ad/RSV-TK | C6 glioma | Tumor treatment/significant tumor de- crease/long-term tumor regrowth |

| Perez-Cruet et al. (1994) | Adv-tl | In vivo: 9L in Fischer rats | Tumor treatment effective for >120 days |

| (10) Metabolic Brain Disease | |||

| Kosuga et al., 2001a | Ad-lacZ, Ad-GUSB | In vivo: monkey |

In vitro enzyme deficiency of MPSVII reduced by transduction with an Ad-expressing GUSB; adenovirally transduced mAEC transplanted into monkey brain to determine their migration and distribution |

| Shen et al., 2001 | Ad-GALC |

In vivo: intraventricular administration in a murine model of human globoid cell leukodystrophy |

Effects of Ad-mediated replacement of GALC in Krabbe disease |

| Kosuga et al., 2001b | Ad-GUSB | In vivo: mice | Adenovirally transduced mAEC overexpressing GUSB transplanted into mice with MPSVII |

| Ghodsi et al., 1998 | Ad-GUSB |

In vivo: intraventricular or intrastriatal injection in MPSVII or wt mice |

Activity of Ad-delivered GUSB is examined up to 84 days postadministration |

| Peltola et al., 1998 | Ad-AGA, Ad-AGU(Fin) |

In vitro and in vivo: primary neuronal cultures from/and mouse model of AGU |

Effects of systemic and intraventricular administration of AD encoding for the deficient enzyme AGA |

| Plumb et al., 1994 | Ad-RSV-rHPRT | In vivo: mice | Utility of Ad encoding HPRT in HPRT-deficient mice is examined |

| (11) Other Applications: Brain Imaging, Pathway Tracing, Substance Abuse | |||

| Umegaki et al. (2002) | Ad-CMV-DopD(2)R | In vivo: rats | PET is shown to be useful for longi- tudinal in vivo assessment of D(2)R expression mediated by an Ad vector in rat brain |

| Ross et al. (1995) | Ad-TK | In vivo: 9L gliosarcoma rat model | Ad-mediated TK and GCV therapy is evaluated with MRI and localized H magnetic resonance spectroscopy |

| Mackler et al. (2000) | Ad-NAC-1 | In vivo: rats | Ad-mediated overexpression of NAC-1 protein affects long-term behavior in psychostimulant abuse |

| Lisovoski et al. (1994) | Ad-RSV-LacZ, Ad type 5 | Spinal cord | Neuroanatomy: cell labeling for morpho- logical studies |

| Kuo et al. (1995) | Ad-RSVlacZ |

In vivo; injection into the laterodorsal striatum |

Suitability of an Ad vector encoding β-galactosidase for neuronal pathways tracing is tested |

| Ridoux et al. (1994a) | Ad-RSVLacZ | CNS, basal ganglia | Pathway tracing in the CNS |

| Abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| Ad | Adenovirus |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AGA | Aspartylglucosaminidase |

| AGU | Aspartylglucosaminuria |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| α1-AT | α1-Antitrypsin |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BCNU | Carmustine |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| bFGF | Basic fibroblastic growth factor |

| BrdC | 5-Bromo-2′-deoxycytidine |

| CAR | Coxsackie and adenovirus receptor |

| CAV2 | Canine adenovirus type 2 |

| CBF | Cerebral blood flow |

| CCNU | 1-(2-Chloroethyl)-3-cyclohexyl-1-nitrosourea |

| CD | Cytosine deaminase |

| CMV | Human cytomegalovirus |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte |

| DA | Dopaminergic |

| DRG | Dorsal root ganglion |

| D(2)R | Dopamine D(2) receptors |

| EAA | Excitatory amino acid |

| FasL | Fas lingand |

| 5-FC | 5-Fluorocytosine |

| FIV | Feline immunodeficiency virus |

| FPI | Fluid percussion injury |

| 5-FU | 5-Fluorouracil |

| GALC | Galactocerebrosidase |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GRP78 | Glucose-regulated protein 78 |

| hGDNF | Human glial cell-line-derived neurotrophic factor |

| GUSB | β-Glucuronidase |

| HCMV major IE | Human cytomegalovirus major immediate early |

| HD | Helper dependent |

| HPRT | Hypoxanthine-guanine-phosphoribosyltransferase |

| HSV1 | Herpes simplex virus type 1 |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-1ra | Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist |

| IRES | Internal ribosomal entry site |

| JBD | JNK-binding domain |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| KA | Kainic acid |

| LTR | Long terminal repeat |

| Luc | Luciferase |

| MIEmCMV | Major immediate early murine CMV |

| MION | Monocrystalline iron oxide nanoparticles |

| MLP | Major late promoter |

| MPSVII | Mucopolysaccharidosis type VII |

| MPTP | 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine/1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| Nls | Nuclear localization signal |

| NSE | Neuron-specific enolase |

| NRSE | Neuron-restrictive silencer element |

| 6-OHDA | 6-Hydroxydopamine |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PF4 | Platelet factor 4 |

| PK | Phosphoglycerate kinase |

| PLGA | Polylactic glycolic acid |

| PS2 | Presenilin 2 |

| RAd | Recombinant adenovirus |

| REST | Repressor element 1 silencing transcription factor |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| RSV-LTR | Rous sarcoma virus-long terminal repeat |

| SCG | Superior cervical ganglia |

| SN | Substantia nigra |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor-β1 |

| TH | Tyrosine hydroxylase |

| TK | Thymidine kinase |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| trkB | Tyrosine receptor kinase B |

| UPAR | Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor |

| UPRT | 5-Fluorouridine 5′-monophosphate |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VP16 | Activation domain of a viral protein |

| WldS protein | Unique protein derived from a spontaneous mutant mouse, characterized by slow Wallerian degeneration |

| Wt | Wild type |

III. Developments in the Use of Adenovirus Recombinants as Vectors

The deletion of the Ad E1 gene region results in a failure of the replication-deficient Ad vector to activate both early and late phase transcription from the viral genome. Consequently expression of only a transgene under the control of a constitutive or cell-type-specific or inducible promoter is achieved in the infected target cell. Although this genetic barrier to adenovirus gene expression is efficient, it is not absolute. Even limited breakthrough of Ad gene expression does occur in many if not most tissues, and can thus be problematic, it may either by itself affect the physiology of the target cell, induce cytotoxic responses, a cellular immune response, as well as provide antigenic epitopes recognized by the adaptive arm of the immune response (Engelhardt et al., 1994; Yang et al., 1994a,b; Thomas et al., 2000b, 2001b; Lowenstein and Castro, 2002; Mahr and Gooding, 1999; Wold et al., 1994, 1999; Hackett et al., 2000; Wood et al., 1996a). Although infections at low multiplicity with E1-deleted vectors are unlikely to lead to high level adenoviral gene expression, the same is not true at high multiplicity of infections such as used in gene therapy applications. This is likely to remain the case, even if deletion of Ela, Elb, and other regions of the adenovirus genomes provides a better block than simply the Ela deletion (Imperiale et al., 1984; Spergel and Chen-Kiang, 1991). Nevertheless extremely high input multiplicities of infection (in excess of 100 or even higher infectious units per cell regularly achieved in in vivo experimental designs) can result in breakthrough of low level expression of the Ad genome (Engelhardt et al., 1994; Kass-Eisler et al., 1994; Yang et al., 1994a,b). A further modification to current vectors is therefore of interest, i.e., the supplementation of deletions in E1, E3, with an additional conditional mutation in E2a, the so-called “second-generation vectors” (Engelhardt et al., 1994; Yang et al., 1994a,b). The E2a region plays a role in activating late phase gene expression. Recombinants carrying this additional mutation have proved to be less reactogenic and permit prolonged expression of the transgene (Engelhardt et al., 1994; Yang et al., 1994a,b). Expression of late genes from the adenoviral genome that are normally expressed only following adenoviral DNA replication suggests that limited replication of the adenoviral genome may occur in some cells. This remains to be proven. In view of the fact that the liver contains proteins that can substitute for E1a function, this topic ought to be investigated carefully.

Further, forskolin can increase the breakthrough to late gene expression. Forskolin results in enhanced levels of intracellular calcium and activation of the transcription factor cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB or ATF), a factor that is known to bind and stimulate transcription from the Ad early promoter (Muchardt et al., 1990). It is therefore not surprising that forskolin treatment of cells infected with a replication-deficient Ad recombinant can enhance breakthrough to late phase gene expression. Both a high input multiplicity of infection (around the site of virus inoculation or instillation) and elevated calcium levels are likely to occur in transduced cells following in vivo gene transfer. Both these phenomena are very likely to coincide in neurons surrounding the site of adenovirus direct injection into the brain. Physiological conditions at the site of gene transfer could thus further regulate transgene expression from viral vectors.

The induction of an immune response to elements of the Ad vector is now perceived as a significant limitation of the vector in long-term gene therapy protocols, especially when systemic administration is needed. Several groups have characterized the effects of the virions on brain inflammation, and the effects of peripheral injections on the stimulation of adaptive immune responses (Byrnes et al., 1995, 1996a,b; Matyszak and Perry, 1996; Wood et al., 1996a; Wood, 1996; Morral et al., 1997; Matyszak 1998; Perry, 1998; Gerdes et al., 2000; Thomas et al., 2000b, 2001a,b, 2002). The effects of each of these on transgene expression are reviewed in detail elsewhere (Lowenstein and Castro, 2002). Although gene transduction remains possible in seropositive animal models and thus possibly in human clinical trials, repeated exposure to viral antigens will be expected to reduce the efficiency of gene transfer. The lack of need to utilize adjuvant when immunizing against adenovirus indicates that even small amounts of vectors leaking into the peripheral immune compartments could activate such immune responses. In the nervous system elements of the adaptive immune response, but not innate inflammatory processes and cells, are able to completely shut-off transgene expression, apparently in the absence of cytotoxicity (unpublished observations). Whether similar phenomena occur in other organs remains to be determined.

Utilizing different Ad serotypes as vectors in sequential treatment administrations could to some extent circumvent this problem. Breakthrough to early phase transcription was demonstrated by the identification of a humoral immune response to early phase proteins. In a mouse model breakthrough has been strongly correlated with the induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response to adenovirus proteins, which is responsible both for an inflammatory response and an elimination of target cells expressing a transgene (Yang et al., 1994a,b). It has, however, been difficult to conclusively demonstrate that such CTLs are effectively cytotoxic in vivo, and thus some of these results and their implications for immune-mediated killing of target cells have been challenged (Wadsworth et al., 1997). Many experiments have been performed using extremely high doses of input virus. If lower doses of adenovirus recombinant are inoculated into a mouse, major histocompatibility complex-I (MHC-I) responses specific for a viral transgene in the absence of a detectable response to the vector can be induced (Schadeck et al., 1999). However, high input doses of recombinant may be essential for efficient in vivo gene transfer.

It is also important to consider that many experiments are performed in non-permissive or semipermissive species (Ginsberg et al., 1991; Ross and Ziff, 1992), e.g., mice, rats, and nonhuman primates. In such systems, Ad E1 recombinants are unable to replicate due to a “species block.” It would thus be useful to test recombinants in a more relevant species, such as “permissive” cotton rat (Sigmoidon hispidus), to determine whether cell-specific factors in addition to species-specific factors regulate the capacity of adenovirus to replicate in particular target organs (Oualikene et al., 1994).

Many researchers see the current cloning capacity of ~7–8 kb as a limitation toward the more general applicability of adenoviral vectors. There is a stringent limitation exerted by the adenovirus particle, which will package only an additional 3% ( ~1 kb) in addition to the full-length viral genome (Shenk, 1995). Thus, a new generation of high-capacity helper-dependent adenoviral vectors (also known as “gutless” or “gutted” vectors; HD-Ad) has been developed that is devoid of all viral coding sequences (Fig. 2) (Kochanek et al., 1996; Mitani et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1997, 1999; Morral et al., 1998; Morsy et al., 1998; Schiedner et al., 1998; Burcin et al., 1999; Sandig et al., 2000; Akagi et al., 1997; Maione et al., 2001; Parks et al., 1996, 1999a,b; Cregan et al., 2000; Ng et al., 2001, 2002; Umana et al., 2001; Lowenstein et al., 2002). These vectors have a minimum requirement for the extreme termini of the linear adenovirus genome, containing only those cis-acting elements for viral DNA replication and packaging, mainly the inverted terminal repeat (ITR) sequences and packaging signal. Because these elements are contained ~500 bp from the ends of the genome (Grable and Hearing, 1992), helper-dependent vectors have the potential encode range of few hundred base pairs to up to ~30 kb of foreign DNA, which is close to the size of the native genome.

Fig. 2.

An E1-, E3-deleted helper adenovirus (FL helper) with a packaging signal sensitive to FLP3-mediated excision. (A) FL helper was generated by homologous recombination in 293 cells after cotransfection with plasmid pΔE1sp1A-2xFRT and pBHG10-CMVluc-I. The bottom half of the figure indicates the left-end region of the helper virus genome, before and after FLP3-mediated recombination; the figure also indicates the location of the PCR primers used to determine excision of the packaging signal, ψ (flanked by black arrows). (B) Production of gutless adenoviral vectors. Diagram of an ideal gene delivery vector for neurological gene therapy using the “gutless” adenoviral vector. The packaging signal of the helper virus, flanked by FRT sites, is excised after growth in 293 cells expressing FLPe recombinase. The cloning capacity of this system (N30 kbp) will enable the simultaneous use of two or more therapeutic genes and also includes inducible promoter systems. (See Color Insert.)

HD-Ad are copropagated with an E1-deleted helper virus, which provides in trans all of the proteins required for packaging the vector. Up to now, several systems have been developed to prevent packaging of the helper virus. The Cre/loxP-based system for the generation of HD-Ad involves the use of a first-generation helper virus, where the packaging signal is flanked by loxP recognition sites (Hardy et al., 1997). Infection of Cre-expressing 293 cells with the helper virus results in excision of the viral packaging signal, rendering the helper virus DNA unpackagable but still able to replicate and provide helper functions for HD-Ad vector propagation (Chen et al., 1996). Purification by cesium chloride centrifugation is necessary to reduce the titer of the helper virus to negligible levels, typically ranging from 0.1 to 0.01% of the HD-Ad titer (Morsy et al., 1998). Recently, another Flp/frt-base system has been developed. The Flp recombinase was used in place of Cre, and shown to excise the frt-flanked packaging signal in helper virus efficiently (Lowenstein and Castro, 2001; Ng et al., 2001; Umana et al., 2001). The most recent improvement to this system is the development a new Cre-expressing cell line based on E2T, an E1 and E2a complementary cell line (Zhou et al., 2001). Thus an E1 and E2a double-deleted helper virus can be used with the new cell line to produce HD-Ad vector with low helper contamination, further improving HD vector safety (Zhou et al., 2001). Compared with first-generation adenovirus vectors, the HD-Ad vector can efficiently transduce a wide variety of cell types from numerous species in a cell cycle-independent manner as first generation, but HD-Ad vector has the added advantage of increased cloning capacity, reduced toxicity and immune responses, and prolonged stable transgene expression in vivo (Schiedner et al., 1998; Thomas et al., 2000a,b; Thomas et al., 2001a,b). This system is essentially analogous to herpes simplex virus (HSV1) amplicons and shares some of their limitations (Lowenstein, 1994, 1995), e.g., low titers and the presence of variable amounts of helper virus in viral stocks, although novel systems that produce vectors in a helper-free fashion are now available (Wade-Martins et al., 2001; Logvinoff and Epstein, 2001; Wang et al., 2002). Eventually, it should be possible to develop this system so that the recombinants can be produced in the absence of helper virus to generate a safer vector with markedly reduced potential to be reactogenic.

IV. Adenoviral Recombinant Vectors: Applications to Basic Neuroscience

The technology for gene transfer to the brain has progressed substantially during the past 5 years, and new improved systems are being rapidly developed. Table I compares the major systems for gene transfer into neurons in vitro and into the brain in vivo. Vectors vary dramatically in their efficiency of gene transfer, longevity of expression, associate toxicity, and size of the transgene they can harbor. Some vectors mainly direct short-term expression of transgenes, either because of their intrinsic toxicity [e.g., Semliki Forest virus (SFV), vaccinia], or promoter shut-off, a poorly understood phenomenon by which promoters within viral vectors eventually stop being active in spite of the vector genomes being present. Adenoviruses mediate long-term transgene expression in the central nervous system (up to over 1 year) in naive (nonimmunized) animals. Immunization completely eliminates expression from first-generation vectors but not high-capacity helper-dependent adenoviral vectors, whereas in preimmunized animals, transgene expression mediated by first-generation adenoviruses declines within 2–4 weeks postinjection, but expression from the high-capacity helper-dependent adenoviral vectors is reduced only to approximately 50% and stays stable thereafter (Thomas et al., 2000a,b; Thomas et al., 2001b).

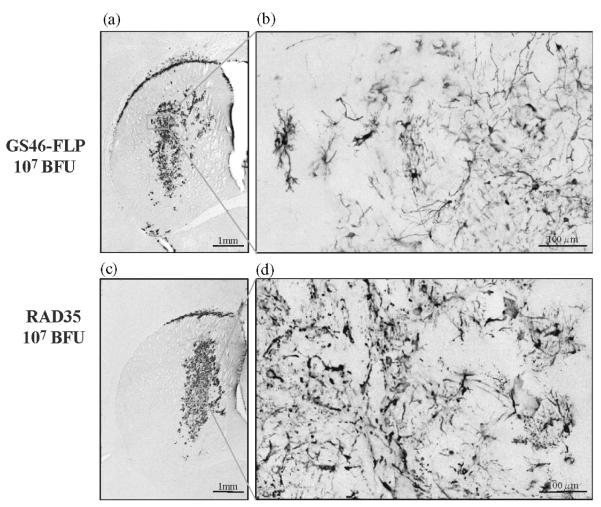

In 1993 four groups independently reported for the first time in vivo gene transfer into several types of brain cells using adenovirus recombinant encoding β-galactosidase (Akli et al., 1993; Bajocchi et al., 1993; Davidson et al., 1993; Le Gal La Salle et al., 1993). Since these initial breakthroughs, there has been a logarithmic increase of original papers using adenovirus recombinants to transduce brain cells (see Table II). Although there is some specificity in the capacity of different adenovirus serotypes to infect/express in different target cells (Acsadi et al., 1994a,b; Bessereau et al., 1994; Grubb et al., 1994; Millecamps et al., 1999) a recombinant adenovirus-derived vector can indeed express trans-genes in all brain cells, e.g., neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, ependymal cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, endothelial blood vessel cells, retinal pigment epithelium, photoreceptors, as well as retinal neurons proper, and peripheral nerve Schwann cells either in vivo or in vitro (Table II; Akli et al., 1993; Bajocchi et al., 1993; Caillaud et al., 1993; Davidson et al., 1993; Le Gal La Salle et al., 1993; Bain et al., 1994; Bennett et al., 1994; Jomary et al., 1994; Li et al., 1994; Byrnes et al., 1995; Lowenstein, 1995; Shering et al., 1997; Morelli et al., 1999; Smith-Arica et al., 2000; Thomas et al., 2000a,b; Umana et al., 2001; Thomas et al., 2000b, 2001a,b, 2002).

While initial experiments were performed using recombinant adenovirus to transfer marker proteins into the brains of both rodents and primates, recombinant vectors encoding therapeutic genes for treatment of neurological diseases have now been generated (Table III) (Chen et al., 1994; Davidson et al., 1994; Perez-Cruet et al., 1994; Shewach et al., 1994; Lowenstein, 1995; Geddes et al., 1997; Ambar et al., 1999; Dewey et al., 1999; Gupta et al., 2001; Bohn et al., 1999; Lawrence et al., 1999; Bohn, 2000; Connor et al., 1999, 2001; Kozlowski et al., 2000, 2001; Amalfitano and Parks, 2002). Expression of transgenes after in vivo administration of vectors to the brain was detected up to 5–6 months and even after 18 months postinoculation (Geddes et al., 1997; Thomas et al., 2000a,b; Thomas et al., 2000b, 2001a,b; Zermansky et al., 2001).

TABLE III.

Neurological Gene Therapy:What Can Be Achieved with Adenovirus Vectors?a

| Noninherited |

Inherited |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Tumors | PDc | HD | CMT | Leukodystrophies | Lesch–Nyhan | Frax-A |

| Outcome | Fatal | Fatal | Fatal | Nonfatal | Fatal | Fatal | Nonfatal |

| Distribution | Focal | Focal | Diffuse | Diffuse | Diffuse | Diffuse | Diffuse |

| Age at manifestation | Variable | Late | Variable | Variable | Early | Early | Prenatal |

| Presymptomatic detectionb | No | No | Yes | Yesd | Yesd | Yesd | Yesd |

| Genotype predicts disease severity |

ND | ND | Yes | Yes | Yes/noe | Yes | No |

| Gene cloned | Yesf | Yesg | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Expression needed | Short term | Long term | Long term | Long term | Long term | Long term | Long term |

| Experimental | Tumor | Dopamine | Reduce | Normalize | BMT | Express | Express |

| Gene therapy | Cell killing | Replacement, GDNF, AADC |

Expression of expanded allele |

PMP22 expression |

Expressing missing genes |

Brain | Brain |

| Clinically relevant available therapeutic protocols |

Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Available adenoviral vectors | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

HD, Huntington’s disease; CMT, Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (the commonest genetic alteration is duplication of the region of chromosome 17p11.2 containing the PMP 22 gene); Frax-A, fragile X syndrome type A; PD, Parkinson’s disease (idiopathic); BMT, bone marrow transplant. This table is modified from MacMillan and Lowenstein (1996).

Even if presymptomatic detection is available, it is not done routinely during pregnancies; it is performed only if there is any suspicion due to a positive family history.

The primary pathology is loss of dopaminergic neurons from the pars compacta of the substantia nigra, but other lesions within PD are distributed throughout the brain.

Molecular genetic diagnosis is possible in the fetus, but it is arguable whether this would be prior to the occurrence of pathological changes.

Genotype predicts disease severity in metachromatic and Krabbe’s leukodystrophy, but not yet in adrenoleukodystrophy.

The genes mutated in inherited brain tumors have been cloned. However, therapeutic gene therapy is more likely to utilize the transduction of cytotoxic genes to eliminate tumor cells.

The genes for tyrosine hyroxylase and dopa decarboxylase have been cloned. These are not, however, mutated in either familial or sporadic PD.

Other examples of adenoviruses encoding therapeutic transgenes for preclinical applications include recombinant adenoviral vectors encoding hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT), which could be utilized in the treatment of the Lesch–Nyhan syndrome. Although these vectors have mainly been utilized to transduce HPRT in primate (Davidson et al., 1994) and rodent brains (Davidson et al., 1994; Lowenstein, 1995; Southgate et al., 2001), there is yet no published account of their capacity to complement an HPRT deficiency in animal models for the Lesch–Nyhan syndrome. Adenovirus vectors expressing tyrosine hyroxylase, and their therapeutic efficacy in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease, have been reported (Horellou et al., 1994; Corti et al., 1999a,b; Hida et al., 1999). Recombinant adenoviruses encoding neuroprotrective factors such as glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), aimed to prevent dopaminergic neuron degeneration in a rat model of Parkinson disease, have also been successfully developed (Bilang-Bleuel et al., 1997; Choi-Lundberg et al., 1997, 1998; Bohn et al., 1999; Lawrence et al., 1999; Bohn, 2000; Connor et al., 1999, 2001; Kozlowski et al., 2000, 2001).

Because adenovirus recombinants can be used to transduce essentially all brain cells, they have also been postulated to be applicable to gene therapy protocols for the treatment of brain tumors, by utilizing them to deliver cytotoxic genes directly into the tumors. Thus, a number of groups have utilized several adenovirus recombinants, e.g., expressing HSV1 thymidine kinase or Fas ligand, Fas receptor, or p53, under the control of viral promoters. In experimental paradigms the use of these viruses appears to be promising (Badie et al., 1994; Boviatsis et al., 1994; Brody et al., 1994a; Chen et al., 1994; Perez-Cruet et al., 1994; Shewach et al., 1994; Ambar et al., 1999; Dewey et al., 1999; Morelli et al., 1999; Shinoura et al., 2000a,b; Shono et al., 2002; see George et al., this volume).

Recombinant retroviruses have been used in the treatment of brain tumors (Ram et al., 1993; Palu et al., 1999; Tamura et al., 2001), and replication-competent and conditional HSV1 vectors as well as HSV1 amplicon vectors have also been tried (Martuza et al., 1991; Markert et al., 1993; Kramm et al., 1997; Pechan et al., 1999; Herrlinger et al., 2000; Papanastassiou et al., 2002; see Hu and Coffin, this volume). In a recent phase I clinical trial the efficacy and safety profiles of retrovirus and adenovirus expressing HSVI TK have been compared (Sandmair et al., 2000). Adenoviruses showed very promising results, both in terms of their safety and also their efficacy in glioma growth control (Sandmair et al., 2000). However, the only vector system that has progressed to a phase III clinical trial has been a retroviral vector expressing HSV-1 thymidine kinase. The trial was halted because of the absence of positive effects in the gene therapy arm of patients treated (Rainov, 2000; Rainov and Kramm, 2001). With Phase I and II being essentially toxicity trials, Phase III efficacy clinical trials are crucial in order to determine whether any of the new therapies are indeed effective, because such results can be obtained only rarely from the much smaller Phase I and II trials.

Two groups have also made interesting observations on the use of adenovirus recombinants that should be of interest to neuroanatomists, namely the use of adenovirus for pathway tracing and cell labeling. Ridoux and colleagues (1994a) observed retrograde labeling of substantia nigra neurons after injections of recombinants expressing β-galactosidase into the striatum; similar results were also observed by Byrnes et al. (1995). Thus, replication-defective adenovirus could be used for retrograde labeling of neuronal pathways. Interestingly, HSV1-derived recombinants can also be used to trace neuronal pathways (Ugolini et al., 1989), with some recombinants being specific for anterograde transport and others for retrograde transport (Zemanick et al., 1991), while certain pseudorabies recombinants have been shown to be specific markers for individual neuronal circuits and capable of retrograde axonal transport (Card et al., 1991, 1992; Mazarakis et al., 2001; Enquist et al., 1998; DeFalco et al., 2001). Lisovoski et al. (1994) utilized adenovirus recombinants to label neurons of the spinal cord at different stages of development to study their morphological development. The staining they obtained after in vivo administration filled the dendritic arbors of neurons, thus allowing for their morphological and morphometric examination during spinal cord development.

An effective way of delivering gene products to the brain, rather than by introducing it into constituent cells, is by transplanting genetically engineered cells directly into the CNS. So far, most genetically engineered cells expressing trangenes for transplantation have been transduced with recombinant retroviral vectors. Ridoux et al., (1994b) have used adenovirus to tranduce primary cultures of rat astrocytes in vitro and then transplanted these into the CNS of host rats. Expression of transgene was detected for at least 5 months. Thus, adenovirus might constitute an alternative to retrovirus for transducing cells in preparation for transplantation into the brain. In many cases expression from retroviral vectors ceases after a few days to a few weeks; thus, it will be interesting to compare both systems vis-à-vis length of transgene expression.

Expression of transgenes after the administration of adenovirus recombinants into adult brains has been seen by some groups to last from 6 to 18 months. It also was reported that injection of recombinants into neonates has allowed expression to be sustained over periods up to a year. Long-term modulation of the immune response and the elucidation of its exact role in the regulation of long-term expression from adenoviral recombinants administered into the CNS will be crucial to achieve stable expression over a long period of time, which will be needed to implement gene therapy for chronic neurological disorders in humans. (Stratford-Perricaudet et al., 1990; Kass-Eisler et al., 1994; Geddes et al., 1997; Thomas et al., 2000a,b; Thomas et al., 2000b, 2001a,b; Zermansky et al., 2001).

Scant information is available on the interactions of adenovirus with the brain. Thus it will be of great importance to explore this field, e.g., adenovirus entry into brain cells, transport to the nucleus, and viral replication in neurons of permissive species. In addition, the effect of adenovirus recombinants on the electrophysiology of specific neuronal populations will have to be investigated. It also will be critical to assess the effects of adenoviral delivery into different brain regions on animal behavior. It is surprising that not much work on these topics has been published in the past 5 years.

V. Adenoviral Recombinant Vectors: Applications to Neurological Gene Therapy

Essentially there are two types of applications for which vectors for gene transfer into the brain could be used. Short-term expression could be used, for example, to express cytotoxic products to kill tumor cells, or to provide drugs to block ischemia-induced neurotoxicity. Ideally, the area of brain tissue to be targeted should be focal, and therapeutic benefit should be predicted after short-term transgene expression (Table III). Long term expression would be needed to treat chronic neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, or amyotrophic lateral dystrophy. In this case, the area of brain tissue will be larger, and the results of the therapeutic intervention may not be seen until after several years.

The availability of viral vectors that express short term at high levels of expression could lead to important new treatments for brain diseases. A case in point are brain tumors, which are now being treated experimentally with adenovirus recombinants expressing conditional cytotoxic gene products (Badie et al., 1994; Boviatsis et al., 1994; Brody et al., 1994a,b; Chen et al., 1994; Perez-Cruet et al., 1994; Shewach et al., 1994; Takamiya et al., 1992; Barba et al., 1994; Benedetti et al., 1997; Ram et al., 1997; Bansal and Engelhard, 2000; Ikeda et al., 2000; Trask et al., 2000; Jacobs et al., 2001; Rainov and Kramm, 2001). Brain tumors constitute a good target disease for gene therapy for the following reasons: (1) the disease is focal; (2) the therapeutic objective—the destruction of tumor cells— needs to be achieved within the short term, and this can be done using cytotoxic or conditionally cytotoxic gene products; (3) the disease is life threatening within 6–12 months of diagnosis; (4) no effective treatments are available; and (5) adenovirus-particle-induced inflammation could be a beneficial adjunct to tumor cell elimination. Similarly, replication-deficient and replication-competent HSV1-derived vectors have also been also developed (Martuza et al., 1991; Markert et al., 1993) and these vectors have already been tested in Phase I–III clinical trials (Martuza et al., 1991; Markert et al., 1993, 2000; Rampling et al., 1998, 2000; Rainov, 2000).

Achieving long-term expression in brain following the administration of recombinant vectors will open up the development of gene therapy clinical trials for human neurological diseases where long-term expression is paramount, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and the metabolic and degenerative brain disorders (Amalfitano and Parks, 2002; Hsich et al., 2002; Lowenstein, 2002; Lowenstein and Castro, 2002). What makes it difficult to treat such diseases is that they affect large areas of the brain, many extending throughout large anatomical regions of the human CNS, and they progress relatively slowly over years or decades. For Parkinson’s diseases there are as yet no presymptomatic diagnostic methods available, so treatment can be instituted only when symptoms appear. In families suffering from Huntington’s disease, presymptomatic diagnosis is now possible (Holloway et al., 1994) and this might also soon become possible in Alzheimer’s disease (Saunders et al., 1993; Nalbantoglu et al., 1994; Scinto et al., 1994). The diffuse nature of these diseases has led to the development of other therapeutic interventions that could target genes and their products to different areas located throughout the brain, such as transplantation of genetically engineered cells (Fisher, 1993), the direct intracranial administration of neuronal growth factors (NGF), (Seiger et al., 1993), or more recently the development of embryonic and or neural stem cells. HSV1 (Lokensgard et al., 1994; Burton et al., 2001; Kay et al., 2001; Latchman and Coffin, 2001; Lilley et al., 2001) and adeno-associated virus vectors (Kaplitt et al., 1994; Sanlioglu et al., 2001; Fu et al., 2002; Muramatsu et al., 2002) might also provide alternative vectors to achieve long-term transgene expression in brain for clinical applications in humans.

Although human brain infections caused by adenovirus are extremely rare, it has been reported that adenovirus can cause central nervous system disease, especially in children and immuncompromised individuals, although rare cases have also been described in nonimmunocompromised patients (Ginsberg and Prince, 1994; Engel, 1995; Chirmule et al., 1999; Ginsberg, 1999). Meningoencephalitis, encephalitis, and cerebellar ataxia have been reported in children in association with adenovirus infection of the CNS, mostly adenovirus type 7, 1, 2, or 32 (Chou et al., 1973; Kelsey, 1978; Davis et al., 1988; Osamura et al., 1993). Direct inoculation of adenovirus into the brain of rhesus monkeys has demonstrated that several adenovirus serotypes can cause neuropathology, although adenovirus did not appear to replicate to a great extent in the primate brain (Ginsberg and Prince, 1994; Engel, 1995; Chirmule et al., 1999; Ginsberg, 1999). Also, neuropathology due to an anamnestic reponse of the immune system following the injection of the adenovirus type 5 into the primate brain was recently described (Davidson et al., 1994).

The possibility that latent adenovirus infection might be localized to the human brain, and that adenovirus could enter the brain through infected macrophages from the periphery, has not yet been examined in enough detail, although widespread neuronal inclusions diagnostic of adenovirus particles have been seen in some fatal encephalitis cases (Chou et al., 1973). However, all these data taken together with our observations that wild-type adenovirus can express endogenous proteins in neurons, and brain glial cells, strongly suggest that adenovirus could replicate, or at last express many of its genes after infecting human neurons or glial cells and that expression might proceed for a longer time than predicted, even in the absence of symptoms of encephalitis. If there is a risk of adenoviral encephalitis it will have to be carefully considered at a time adenovirus vector is directly administered into the brain. It is clear that many more studies will be required to clarify the origins of neurotoxicity after direct injections of adenovirus virions into the brain. The use of the completely deleted high-capacity helper-dependent adenoviral vectors will completely avoid these potential complications.

VI. Immune Responses to Recombinant Adenoviral Vectors Delivered into the Brain