Abstract

Loewendorf A, Benedict CA (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, La Jolla, CA, USA). Modulation of host innate and adaptive immune defenses by cytomegalovirus: timing is everything (Symposium).

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (HHV-5, a β-herpesvirus) causes the vast majority of infection-related congenital birth defects, and can trigger severe disease in immune suppressed individuals. The high prevalence of societal infection, the establishment of lifelong persistence and the growing number of immune-related diseases where HCMV is touted as a potential promoter is slowly heightening public awareness to this virus. The millions of years of co-evolution between CMV and the immune system of its host provides for a unique opportunity to study immune defense strategies, and pathogen counterstrategies. Dissecting the timing of the cellular and molecular processes that regulate innate and adaptive immunity to this persistent virus has revealed a complex defense network that is shaped by CMV immune modulation, resulting in a finely tuned host–pathogen relationship.

Keywords: cytokines, herpes virus, immunity, immunology, infectious disease, virology

Cytomegalovirus

The herpesviruses have co-evolved with their vertebrate hosts for more than one hundred million years to establish lifelong infections [1]. Accordingly, all herpesviruses employ a multitude of strategies to modulate the host immune response, facilitating this persistence in the face of a robust innate andadaptive immune response. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV/HHV-5, a β-herpesvirus) is highly prevalent in most populations (50–90%seropositive in the United States, and virtually 100% in the developing countries) and is usually acquired early in life as an asymptomatic, subclinical infection in immune competent persons. However, if primary infection occurs in the developing foetus or neonate (before full immune system development) the consequences can be severe, and HCMV is the most common infectious cause of congenital birth defects [2]. HCMV establishes latency/persistence in monocyte precursors and diverse populations of tissue stromal cells [3, 4]. This is unlike its cousins, herpes simplex virus and Epstein Barr virus (α and γ herpesviruses), whose latency is exclusively restricted to neurons and B cells, respectively. Rapid reactivation of HCMV from this ‘systemic latency’ occurs upon immunosuppression (transplant recipients, AIDS patients, etc.), supporting the notion that constant immune surveillance is required to keep persistent infection in check, and can result in morbidity and/or mortality if not controlled by antiviral drug therapy. Significant evidence associates HCMV to vascular disease, and recent work has revealed potential mechanisms underlying these links [5]. HCMV is also linked to the development of several other chronic inflammatory disorders [6], and specific human malignancies [7, 8]. However, in many of these cases whether the presence of HCMV is causative or merely reactivated/detectable due to altered host immune control in these disease settings remains an open question.

CMV replication is species restricted, and therefore no natural animal model exists for examining HCMV pathogenesis, although a few studies have been performed in SCID-hu mice [9, 10]. Consequently, CMV has been studied extensively in the mouse model (MCMV), which provides several advantages due to the availability of genetically characterized inbred strains. Much work has also been performed in the rat, guinea pig and rhesus monkey models of CMV infection, all of which utilize genetically unique CMVs. All CMVs show significant homology/organization in their genomes of>200 kB, exhibit conserved tissue tropism and temporal regulation of gene expression and display similar pathogenesis. However, significant primary genomic sequence diversity exists between CMVs, and <50% of HCMV orfs have identifiable homologues in MCMV [11, 12]. The greatest sequence divergence is seen in the genomic termini of the CMVs, the area encoding the highest concentration of genes dedicated towards immune modulation. This genomic divergence is not unexpected, as this virus has been evolving in diverse hosts since the appearance of the primordial CMV more than 108 years ago [1]. In turn, CMV has almost certainly impacted the diversification of host immune defense genes, with more than 3% of the mouse genome composing the ‘resistome’ to this virus [13]. Therefore, although the sequences of immune modulatory orfs and their precise modes of action often differ between the CMVs, overall the immune mechanisms that are targeted are largely conserved.

The level of cross-talk between innate and adaptive immune cells that is required for the development of effective immunity is a complex, pathogen-specific matter. In this review, we will focus on: (i) information gleaned from the MCMV model regarding the timing of the innate immune response upon initial infection and subsequent viral spread in vivo, (ii) how this translates to the development of adaptive immunity and (iii) what strategies MCMV utilizes to modulate these host defenses. When possible, we will highlight where viral and host strategies are conserved (or diverge) during HCMV infection. Importantly, as this review focuses on the timing of immune responses, MCMV completes its replication cycle in ~30 h in both cultured fibroblasts and most organs, but HCMV replication takes considerably longer (72–96 h).

The innate response to CMV infection

NK cells and type I interferons (IFNαβ) play a major role in innate control of MCMV replication [14], and not surprisingly MCMV encodes several gene products which target these defenses [15,16]. NK cells are also critical for controlling HCMV infection [17]. Within a decade after the identification of IFNαβ in classical studies more than half a century ago [18], the importance of IFNαβ signalling in regulating MCMV replication in vivo and in vitro was studied by several groups [19-23]. In turn, NK cells were suspected to contribute to MCMV host defenses more than 30 years ago [24, 25], and were definitively shown to be critical by adoptive transfer or depletion studies in the mid 1980s [26, 27]. Since these early studies, the MCMV model has proven to be fertile ground for dissecting the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in regulating these innate defenses, which themselves are also intertwined due to the ability of IFNαβ to activate NK cell effector functions. We will start by reviewing, what regulates IFNαβ production and NK cell function during the first 2 days of MCMV infection in vivo, a biphasic response composed of innate recognition of the initial viral inoculum (peaks ~8 h) followed by a second phase triggered by the initiation of viral spread within the infected host (starts ~36 h).

CMV induction of the initial IFNαβ response: the ‘kick start’

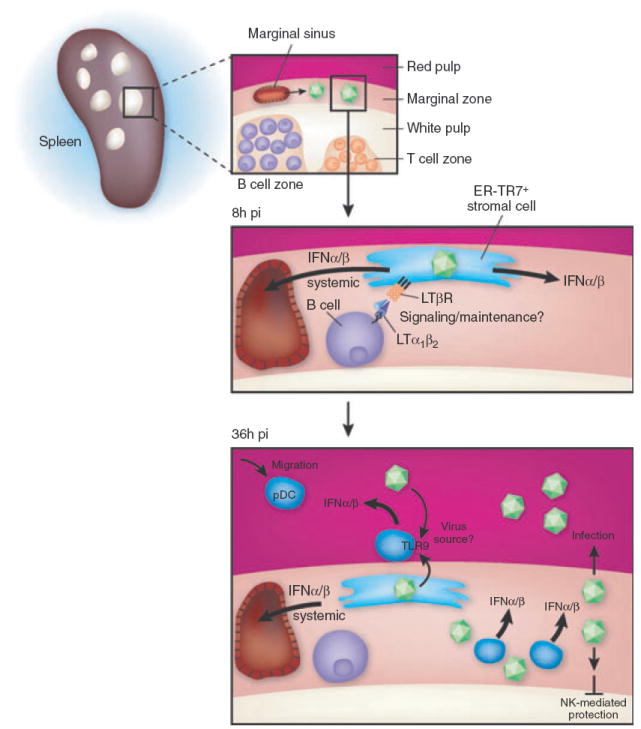

Early studies identified a rapid burst of IFNαβ in the serum detectable ~6 h after intraperitoneal (ip) MCMV infection and waning by 24 h (i.e. ‘systemic’ IFNαβ), and the magnitude of this response varied between mouse strains in a MHC independent manner [22]. As MCMV takes ~30–36 h to complete its replication cycle in vivo [28], it is intuitive that initial IFNαβ production occurs in response to the injected virus inoculum. More recently, the source of this systemic IFNαβ has been shown to be derived from splenic stromal cells, and is dependent upon B cells that express lymphotoxin(LT)αβ [a ligand of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) family] and signal to LTβ-receptor(R) expressing stroma [28, 29] (Fig. 1). This mechanism accounts for ~80–90% of the entire IFNαβ production at 8 h. Importantly, although B cell-expressed LTαβ promotes this first wave of IFNαβ production in the spleen, the liver does not require LTβR signalling to mount the same response at this time [28], and it is currently unknown what cell type/mechanism produces the first IFNαβ in this organ. The initial IFNαβ coming from the stroma is consistent with marginal zone stromal cells being the first target of MCMV infection in the spleen after ip infection ([30] and Fukuyama et al. unpublished data).

Fig. 1.

Regulation of the splenic IFNαβ response: both during initial MCMV infection, and in response to the first round of viral spread. At 8 h postinfection (pi), MCMV virus enters the spleen largely via the marginalzone (MZ) sinus where it predominantly infects MZ stromal cells expressing ER-TR7 and LTβR. The stromal cells require LTα1β2-expressing B cells to maintain their differentiation state, as well as to promote activation of noncanonical NFκB signalling, and these stromal cells secrete the first detectable wave of IFNαβ mRNA peaking at ~8h after infection. The stroma is also the source of the majority of systemic IFNαβ peaking at ~8–12 h. At 36 h pi, pDC preferentially localize to the MZ from the red pulp and produce the vast majority of the splenic and systemic IFNαβ detectable when MCMV is initiating its first round of spread in vivo. pDC utilize a TLR9/MyD88 dependent mechanism to produce IFNαβ, whilst production by the stroma is TLR-independent. In mice containing Ly49H-expressing NK cells, the white pulp is protected from MCMV infection at day 2–3 of infection, and this is dependent upon IFNαβ production as well.

What is the consequence of this initial IFNαβ production? Because the earliest that significant MCMV production can be measured in infected organs is ~36 h after infection, it is somewhat difficult to directly quantify the antiviral consequences of this first wave of innate cytokine production in vivo. However, several indications for it ‘kick-starting’ innate immune control do exist. IFNαβ can act directly on infected cells to inhibit virus production, and can also activate NK and other immune effector cells. Many elegant studies have analysed, how IFNαβ and NK cells regulate MCMV infection at times well after the initial 8 h IFNαβ peak (36 h and later) [31-33], when MCMV has spread within the infected organ and triggered a second wave of IFNαβ by distinct mechanisms (discussed below). However, early work indicated the first wave of MCMV-induced IFNαβ in the spleen can promote NK cell cytotoxicity at 12 h [25]. Furthermore, injection of neutralizing anti-IFNαβ antibody substantially reduced NK cell cytotoxicity when measured at this time [22], confirming the first burst of IFNαβ from splenic stromal cells does have functional consequences. More recent work identified the activation of invariant NK-T-cells (iNKT) during initial MCMV infection, which peaked at 12 h and waned at 24 in both the spleen and liver, and was accompanied by upregulation of iNKT CD25 and CD69 expression but no production of IFNγ [34]. In vitro studies, where human dendritic cell (DC) were exposed to HSV or HCMV also suggested that human NK-T-cells can be activated in response to herpesvirus ‘danger signals’ [35].

Initial IFNαβ induction during CMV infection, a role for NFκB

LTαβ-LTβR-regulation of initial IFNαβ production during CMV infection has also been examined in a model of HCMV infection of cultured fibroblasts. Triggering LTβR signalling within the first 4 h of HCMV infection resulted in substantially higher levels of IFNβ production, which in turn inhibited HCMV spread within the culture via a noncytolytic mechanism [36]. The addition of IL-2-activated NK cells at low effector: target ratios 4 h after infection similarly inhibited HCMV spread by inducing IFNβ from the fibroblasts, with IFNγ produced by the NK cells also contributing [37]. The ability of LTβR signalling to induce higher levels of IFNβ from HCMV-infected cell cultures was strictly dependent upon activation of NFκB [36], perhaps not surprisingly as NFκB is a key component of the IFNβ transcriptional ‘enhancesome’ [38]. LTβR ‘cosignals’ delivered during the first few hours of HCMV or MCMV infection do not appear to alter the activation of IRF3 in cultured fibroblasts (Benedict, unpublished data), another key component of the IFNβ enhancesome [39]. Notably, enhanced induction of IFNβ upon initial HCMV infection is not unique to LTβR signalling, as TNFR1 signalling [36, 37] and overexpression of RIP2/RICK/CARDIAK [40] also induced higher IFNβ via a NFκB-dependent mechanism. Prolonged treatment of fibroblasts with IL-1β prior to HCMV infection also induced higher IFNβ levels, although a direct connection between IL-1β and NFκB was not demonstrated in this study [41]. A role for NFκB in LTβR-regulation of initial IFNαβ production from splenic stromal cells is also supported, as aly/aly mice have a severely compromised response at 8 h after MCMV infection (aly/aly mice contain a spontaneous mutation in the NFκB interacting kinase (NIK) [42]) [28]. Co-injecting an agonistic anti-LTβR antibody 4 h prior to MCMV infection of LTαβ deficient mice restores IFNαβ production to some degree, suggesting that triggering NIK-dependent NFκB signalling may also function as a cosignal in vivo. However, anti-LTβR does not completely restore IFNαβ (~50%), and injecting anti-LTβR antibody 4 h prior to MCMV infection is more efficacious then co-injecting it with the virus (Schneider and Benedict, unpublished data). Consequently, it is possible that altered differentiation of marginal zone stromal cells in mice lacking either LTβR or noncanonical NFκB signalling also contributes to the defective IFNαβ response observed at 8 h after MCMV infection [43].

HCMV and MCMV differ in their restriction of initial IFNαβ induction

IFNαβ mRNA peaks in the spleen and liver at ~8 h after ip infection, and returns to baseline levels at 24 h [28]. MCMV gene expression is just becoming detectable at 4 h [28], indicating IFNαβ mRNA peaks in splenic stromal cells within ~4–6 h after encountering the MCMV particle. For HCMV, infection of cultured fibroblasts with ultraviolet light inactivated virus (UV) induces dramatically higher IFNβ mRNA levels within the first 4–6 h when compared with replication-competent HCMV [36, 44, 45]. This block is likely due to the inability of UV HCMV to express the immediate-early 2 protein (IE2/IE86), which blocks induction of IFNβ and other inflammatory chemokines within hours after HCMV infection [45, 46]. Interestingly, IE2 does not block nuclear translocation of the RelA/p50 NFκB heterodimer induced by HCMV infection, but instead blocks its DNA binding activity by an unknown mechanism [46]. In addition to blocking NFκB DNA binding induced by HCMV, overexpression of IE2 can also block extrinsic activation of NFκB by TNF [46]. As discussed earlier, LTβR/TNFR1 and other NFκB inducing stimuli can enhance IFNβ transcription when they signal concurrently with HCMV infection (or within 2–4 h) [36]. This is an important point, as IE2 would potentially moderate the ability of these signals toamplify IFNβ production by blocking extrinsic NFκB activation. In fact, a careful timecourse analysis of TNF-induced NFκB DNA binding activity in HCMV-infected cells showed a modest decrease by 8 h post infection, but not by 4 h [47]. A much more dramatic block to the ability of TNF and IL-1β to induce NFκB activation is seen at later times of HCMV infection(48–72 h) [47,48], but at this time significant downregulation of TNFR1 from the surface of infected cells also occurs [47,49].

MCMV also restricts NFκB activation by extrinsic TNF signalling in macrophages at 18 h after infection [50], but downregulation of TNFR1 cell surface levels was postulated to be responsible for this block [50]. If MCMV utilizes mechanism(s) similar to HCMV to restrict the initial transcription of IFNαβ, injection of UV MCMV in vivo should result in significantly higher levels of IFNαβ mRNA in splenic stromal cells. However, no differences in the level of splenic IFNαβ mRNA at 8 h is seen when injecting UV MCMV [28], suggesting MCMV does not employ a similar rapid mechanism to dampen the initial induction of IFNαβ transcription. This is consistent with results indicating that UV MCMV induces similar peak levels of IFNβ mRNA in cultured fibroblasts 3–4 h after exposure to the virus ([51] and Benedict unpublished data). This does not mean; however, that MCMV does not employ alternate mechanisms to attenuate IFNαβ transcription. In the same studies, where UV MCMV and wildtype virus induced an equivalent peak of IFNβ mRNA at 3–4 h, a transcription-dependent mechanism(s) restricted the duration of IFNβ transcription over the next 6 h [51]. A plausible explanation for this result might be that MCMV attenuates IFNβ mRNA expression in fibroblasts by inhibiting the IFNαβ ‘positive feedback loop’ [52]. However, studies using several MCMV mutants lacking specific orfs known (M27 [53]), or thought (M83 and M84), to restrict IFNαβ signalling ininfected cells suggested this is not the case.

Importantly, there are a variety of mechanisms employed by mouse, human and rhesus CMV to block the downstream effects of IFNαβ signalling in infected cells. These have been recently reviewed [16, 54], and therefore we will not dwell on them extensively. Although, these mechanisms could in theory restrict the maximal induction level of IFNαβ by restricting the feedback loop, there is no direct evidence for this to date. Notably, the protein derived from the M27 orf is the only known MCMV protein to inhibit IFNαβ signalling by inducing degradation of STAT2 [53], but M27 does not alter IFNαβ induction upon infection [51]. M27 protein is detectable within 4 h, and by 8 h IFNα signalling is already dampened in MCMV-infected cell cultures.

CMV restricts cell death upon initial infection

Programmed cell suicide (i.e. apoptosis) has the potential to serve as an effective strategy to restrict viral replication/spread at very early points in the first populations of infected cells. Consequently, virtually all viruses have developed strategies to block apoptosis at multiple levels, including CMV. CMV encodes several gene products restricting the activation of both the intrinsic (i.e. mitochondria/Bcl-2 dependent) and extrinsic (i.e. death-receptor mediated) pathways, and these have been recently reviewed [55-57]. To highlight very recent data, the M45 protein of MCMV targets the newly characterized ‘necroptotic’ cell death pathway [58] by binding to receptor interacting protein 1 (RIP1) and RIP3 [59-61]. M45 contains both a RIP homotypic interaction motif (RHIM) domain as well as a ribonucleotide reductase homology domain, and was originally shown to be absolutely critical for MCMV to replicate both in cultured endothelial cells and to establish a productive infection in vivo [62]. A functional M45 RHIM domain is required to block MCMV-induced endothelial cell death [60], indicating that MCMV infection triggers the initiation of necroptosis, but M45 subsequently blocks it. Very recent results suggest that RIP3 is the critical adaptor that mediates MCMV-induced necroptosis, and is inhibited byM45 (Upton and Mocarski, personal communication). Additionally, M45 binding of RIP1 and RIP3 via its RHIM domain can sequester these adaptors and restrict their ability to bind to DAI/ZBP1 [61], a DNA-sensing receptor localized to the cell cytoplasm that induces IFNαβ production [63]. Consequently, M45 has the potential to restrict DAI-mediated induction of IFNαβ in MCMV-infected target T-cells, but no evidence of DAI regulating the cell-intrinsic response to MCMV infection currently exists. Very recently, however, DAI has been implicated in the induction of IFNβ during HCMV infection of cultured fibroblasts [64].

The second phase of the innate response during acute CMV infection: responding to virus spread

A large body of elegant work exists characterizing the molecular and cellular regulation of innate defenses to MCMV infection at ~36 h after initial infection, a time-point after MCMV has replicated and spread once within infected organs in vivo [28]. It has been known for some time that NK cell activation is biphasic over the first 36 h of MCMV infection [25], and additional work suggested the same for the IFNαβ response [32]. The genetic polymorphism existing between inbred mouse strains has allowed for the characterization of specific molecular and cellular requirements that regulate innate defense to MCMV infection, and these have been reviewed recently elsewhere [14, 65]. Importantly, the function of the Ly49H NK cell activating receptor in the commonly used C57BL/6 (B6) mice, and the lack of it in Balb/c mice, contributes at multiple levels to the development of innate defenses. Ly49H binds to its MCMV expressed ‘ligand’, m157, resulting in robust activation of the ~50% of NK cells that express this activating receptor in select mouse strains [66]. Consequently, the Ly49H and m157 ‘status’ must always be considered when interpreting experimental results. We have not discussed the functional consequences of the Ly49H-m157 axis to this point in the review, as we consider it unlikely to contribute significantly during the first 12 h of in vivo infection. However, as we will now discuss how IFNαβ and NK cells regulate the first round of MCMV spread in vivo, it clearly must be considered.

DC production of IFNαβ in response to MCMV spread within the spleen

Starting at ~36 h after ip infection of B6 mice with MCMV, DC are major producers of IFNαβ via an LTβR-independent mechanism in the spleen. When splenocytes (excluding stromal cells) were harvested at this time and cultured ex vivo, dendritic cell populations produced >95%of the IFNαβ [67]. Subsequent ex vivo analysis revealed that plasmacytoid DC (pDC) produced significantly more IFNα and other innate cytokines (IL-12, TNF, MIP-1α) on a per cell basis when compared to conventional DC (cDC) subsets in the spleen at 36 h [68]. The first in vivo pDC depletion studies (utilizing an anti-Ly6G/C antibody) indicated that systemic IFNαβ levels at 36 h after MCMV infection are derived from pDC (>95%reduction) [67], and this result was confirmed using a more specific depleting antibody (anti-PDCA1, >85% reduction) [69]. Detailed flow cytometry studies confirmed that splenic pDC are the major producers of IFNαβ, TNF and IL-12 on a per cell basis at 36 h in B6 mice [70]. Importantly, liver-resident pDC do not produce significant levels of IFNαβ at 36 h after MCMV infection [70], even though IFNαβ is present at high levels in the liver at this time. Consequently, the data indicates that systemic IFNαβ levels are largely derived from the spleen at 36 h, and is consistent with results indicating that the spleen is also the major source of systemic IFNαβ at 8 h after MCMV infection [28].

The Toll-like receptors (TLR)-dependent pathways that regulate IFNαβ production in response to MCMV spread

The explosion of research in recent years examining the TLR has certainly impacted the CMV field [71], and much is known regarding how TLRs promote innate immunity during MCMV infection. Two initial studies identified TLR9 as regulating the innate response to MCMV infection in vivo [69, 72]. The first utilized TLR9CpG1 ENU mutant B6 mice [72] and the other examined Balb/c mice genetically deleted for TLR9 expression (i.e. −/− mice) [69]. In this work, >95% and ~75–80%reduction in systemic IFNαβ levels was observed 36 h after MCMV infection, respectively. Another study confirmed the decrease in systemic IFNαβ levels in TLR9−/− B6 mice at 36 h (~70% reduction) [73], and two other groups observed that systemic IFNαβ levels trended lower in TLR9−/−) mice at 36 h, although the results did not achieve statistical significance [74, 75]. It is possible these relatively minor discrepancies seen in TLR9−/− mice may be due to different doses or preps/strains of MCMV utilized in these experiments. Recently, TLR7 has been shown to function redundantly with TLR9 to promote systemic IFNαβ production in B6 mice infected with MCMV, with TLR7−/−TLR9−/−) double-deficient mice having >95% reduction in systemic IFNαβ levels at 36 h. This is intriguing, as both these TLRs interact directly with the ER-resident membrane protein UNC93B [76], a protein critical for the 36-h systemic IFNαβ response to MCMV (>95% reduction in an ENU-generated mutant) [77]. MCMV infection of MyD88−/−) B6 mice, the adaptor required for both TLR7 and TLR9 signalling, resulted in >90% reduction in systemic IFNαβ levels at 36 h in four independent studies [69,72,74,75].

TLR3s role in promoting systemic IFNαβ production at 36 h after MCMV infection is still somewhat un-clear, as initial studies in TLR3)−/−) B6 mice have shown a modest reduction (~60%) [72], but subsequent studies show no defect [74]. This discrepancy was not resolved, when examining the contribution of the essential adaptor for TLR3 signalling, TRIF, as TRIFLPS2 B6 ENU mutant mice show >95% reductions in serum IFNαβ levels at 36 h [78], whilst B6 TRIF−/−) mice are reported to be normal [74]. It is possible that the generation of the TRIFLPS2 mice on a ‘pure’ B6 background might explain this difference, as the 129 strain of mice (which compose a certain percentage of theB6 TRIF−/− mice genome, even after extensive backcrossing) encode an ‘alternative’ pathway to respond to TLR3/TRIF signals [79]. Additionally, TLR3 also interacts with UNC93B to signal appropriately [76, 77]. Consequently, all three of these TLRs (3, 7 and 9) may function redundantly to some degree to promote MCMV-induced serum levels of IFNαβ at 36 h. TLR2−/− mice have also been reported to produce ~50% less IFNαβ in the spleen at 36 h after MCMV infection [80]. Although systemic IFNαβ levels were not examined in this study, they would likely be similarly decreased given the defect in the spleen [75]. Although a direct molecular signalling pathway from TLR2−/− leading to IFNαβ transcription is not known [71], a study published as this review went to press indicates thatTLR2may regulate IFNαβ production by ‘inflammatory monocytes’ upon MCMV infection[81].

Timing and tissue specific issues during the first round of MCMV spread

The TLR-dependent mechanisms discussed above that regulate splenic and systemic production of IFNαβ are all operational at 36 h after MCMV infection, and the compiled data are consistent with a model, where splenic pDC are the major producers at this time via a TLR9/MyD88 dependent mechanism. However, again illustrating the extreme complexity and flexibility of the IFNαβ system, systemic IFNαβ levels are normal only at 8 or 12 h later in mice deficient in TLR9, MyD88 or depleted of pDC [69, 73, 74]. The source of this 44–48 h IFNαβ has not been strictly defined, but cDC or stromal cells are likely contributing sources. All the studies depleting pDC or using TLR9 signalling-deficient mice show some residual level of systemic IFNαβ at 36 h, it is simply that pDC contribute the majority of the response at this specific time-point. When infected in culture with MCMV, CD11b+ ‘cDC’ generated from bone marrow(BM)with GM-CSF (GM-CSF BM-DC) produce copious amounts of IFNαβ in a TLR-independent fashion [73]. The division of labour between TLR-dependent recognition of viruses by pDC, and TLR-independent recognition by cDC or stromal cells, is a common theme seen formany RNA viruses, where cytoplasmic receptors like RIG-I/MDA-5 trigger IFNαβ production in non pDC [82]. To date, the TLR-independent pathway(s) that regulate innate sensing of DNA viruses (such as CMV) have not been defined as well as for RNA viruses. Nevertheless, some strides have been made towards identifying the signalling pathways that contribute to TLR-independent regulation of IFNαβ during CMV infection [ 28,61,64].

The roles of IFNαβ and other innate cytokines in regulating innate MCMV defenses in the liver have been largely delineated by the groups of Biron and Salazar-Mather [83]. Although splenic IFNαβ levels were modestly reduced in TLR9−/− mice at 40 h following MCMV infection in their studies (~40%), IFNαβ production was completely independent of TLR9 in the liver at 40 h [84]. However, IFNαβ levels were ~75% decreased in both these organs at this time in MyD88−/− mice. The authors concluded that the responsible cell in the liver producing IFNαβ was a pDC due to its high level of Ly6C expression [84], however, inflammatory monocytes express similarly high levels of Ly6C [81]. Consequently, at the time of this review, it is known that a TLR-dependent, MyD88-indpendent mechanism regulates IFNαβ production in the liver at 40 h, and could be potentially derived from redundant TLR7 signalling in a pDC [75], TLR2-dependent signalling in a liver-recruited inflammatory monocyte [81] or another currently unknown source. It is interesting to note that the 40-h time-point is centred exactly, when the source of IFNαβ production in the spleen is ‘switching’ from being TLR9/MyD88/pDC-derived (36 h) to MyD88/pDC-independent (44 h) [74].

NK cell activation in response to MCMV spread: Day two

IFNαβ promotes activation of NK cell cytotoxicity, and is a primary mechanism by which MCMV replication/spread is controlled at ~36–48 h. Additionally, IL-12 promotes NK cells to produce IFNγ starting at around the 36-h time-point [31]. These two NK effector functions are molecularly separable events, with the IFNαβ/cytotoxicity axis being dependent upon STAT1 and IL-12/IFNγ requiring STAT4 [85]. NK cells utilize both these pathways to restrict acute MCMV replication in all peripheral organs [86, 87], although some organ-specific preferences may exist [88]. IL-18 can also regulate splenic NK cell production of IFNγ at ~1.5 days, but was not found to contribute to activation of liver NK cells [89]. Notably however, these studies did not account for the fact that iNKT-cells comprise the majority of NK1.1+ cells in the liver at 36 h after MCMV infection [90]. Infection of GM-CSF BM-DC with MCMV results in secretion of IL-12 and IL-18, resulting in the production of IFNγ by co-cultured NK cells in an IL-18-dependent fashion [73]. Infection of Flt3-ligand generated BM-DC with MCMV (i.e. a mix of pDC and cDC subsets) activates iNKT-cells to produce IFNγ in a similar co-culture setup, and IL-12 (not IL-18) is the promoting cytokine in this scenario [34]. IL-12 is required for iNKT cell production of IFNγ in the spleen and liver at 36 h after MCMV infection, and still contributes at 40 h in the liver [34, 90]. Interestingly, IFNαβ also promotes IFNγ production by iNKT-cells at 36 and 40 h, highlighting a potential difference in how iNKT and NK are regulated by type I interferons. Importantly, mice deficient for IFNαβ signalling (or depleted for pDC) show both increased levels and altered cellular sources of IL-12 at 36 h after MCMV infection [67, 69, 91].

In general, the DC subsets that produce the bulk of the IFNαβ at 36–48 h afte MCMV infection in vivo also secrete the IL-12 that is responsible for NK and iNKT cell activation, with a few notable exceptions. Although pDC produce the vast majority of IFNαβ in a TLR9/MyD88 dependent manner at 36 h in the spleen (>90%), they only produce ~60–70%of the IL-12 at this time, with the remaining IL-12 being produced largely by the cDC subsets [69, 70, 72]. Consequently, the numbers of splenic NK and iNKT-cells producing IFNγ at 36 h is decreased ~4–5-fold in both TLR9−/−) and MyD88−/−) mice [69, 72, 74], and at 40 h were reduced by ~50%in the livers of MyD88−/− mice, but were normal in livers of TLR9−/− mice [84]. Splenic NK cells isolated at 36 h after MCMV infection of MyD88−/− mice exhibited a modest defect in cytolytic activity [69], but no defect was seen in a second study [74], with the potential difference being the dose of infection (no differences were seen when injecting 10-fold more MCMV). In general, this suggests that the residual production of IFNαβ in the absence of pDC/MyD88 function is still sufficient to activate some NK effector functions during the second day of infection. This is substantiated by the fact that both TLR9−/− and MyD88−/− B6 mice control MCMV replication quite well at 48 h after infection in the spleen [74]. However, NK control breaks down by 3–5 days after infection of these deficient mice, with 100–1000-fold more virus being present in their spleens [69, 72, 74]. Interestingly, TLR9−/− Balb/c mice show no increases in splenic MCMV replication at day 3 or 6 after infection, completely different from what is observed in TLR9−/− B6 mice, suggesting it is the Ly49H-expressing NK cells that are the ultimate effectors activated by the pDC/TLR-dependent pathway [69]. Finally, MyD88−/− B6 mice showed increased levels of MCMV replication in the liver at day 5 after infection, whilst TLR9−/− B6 mice showed no analogous defect [74], perhaps explainable by the inability of TLR2-expressing inflammatory monocytes to function appropriately in the absence of MyD88 [81]. Importantly, as the timing of cellular recruitment to the MCMV-infected liver is dramatically altered in MyD88−/− mice, it is difficult to directly link control of MCMV replication at day 5 to NKcell activation events occurring around day 2 of infection. This is why we have tried to focus largely on NK cell activation that occurs simultaneously with innate cytokine production in this review.

CMV-modulation of the NK cell response

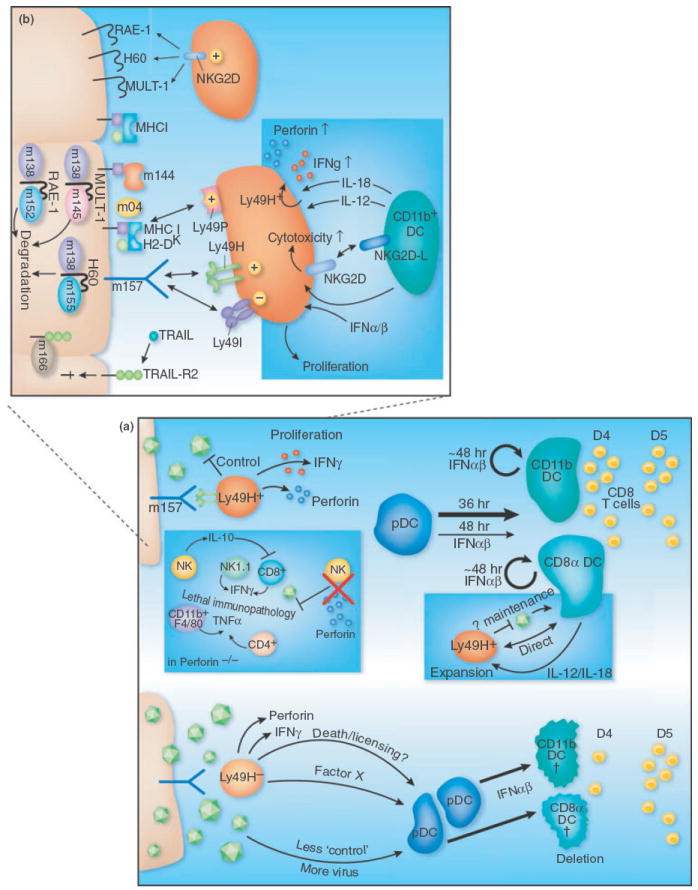

Even though, NK cells are activated by IFNαβ and IL-12/IL-18, MCMV utilizes a variety of strategies to restrict NK cell effector functions, and these have been extensively reviewed recently [15, 92]. Four MCMV gene products are known to inhibit expression of ligands for activating NK cell receptor NKG2D in infected cells (m138, m145, m152 and m155) (Fig. 2): m155 decreases the expression of H60, m145 inhibits mouse UL16-binding protein-like transcript (MULT)-1, m152 inhibits RAE-1 and H60 expression and m138 inhibits mult-1, H60 and RAE varepsilon. Deletion of each of these genes results in reduced viral replication in vivo in an NKG2D and NK cell-dependent fashion, indicating that the viral gene products directly protect infected cells from NK-mediated effect or functions [92]. To the best of our knowledge, none of the various NKG2D ligand modulating genes of MCMV have been analysed in vivo with respect to the precise timing of when these genes dampen NK effector function over the course of the first few days of infection. Nevertheless, elegant work has demonstrated anultimate effect of all these genes in restricting NK-mediated control by day 3–4 [93-96]. The m144 protein (homologous to MHCI) of MCMV also restricts NK cell control [97], but its binding partner is unknown. Aside from the NK-activating function of m157-Ly49H interactions, m157 also binds the Ly49i inhibitory NK cell receptor [98], strong support for the hypothesis that CMV actively drives the evolution of NK cell effector mechanisms in its host [99]. In turn, m04, in complex with H-2DK, also enhances NK cell-recognition of infected cells by binding the activating NK cell receptor Ly49P [100]. Analogously, HCMV encodes six separate gene products and a micro RNA capable of restricting the expression of NK cell activating ligands (UL16, UL18, UL40, UL83, UL141, UL142 and miR-UL112), and the mechanisms by which these gene products function have also been recently reviewed [101]. Hence it is clear that the ‘sum total’ of the host attack and CMV retort at the level of NK cell activation is a very complex process.

Fig. 2.

The role of NK–DC interactions and IFNαβ in regulating both innate and adaptive immune defenses to CMV infection. (a) In mice with Ly49H+ NK cells (top left), binding of this activating receptor by MCMV m157 promotes NK proliferation and acquistion of effector functions, which in turn limit viral replication. Whilst pDC are a major source of IFNαβ at 36h when infecting with ‘normal’ doses of MCMV, their relative production at 44–48 h is marginal compared to cDC (depicted by arrow thickness). However, if low dose MCMV infection is performed, Ly49H+ NK cells restrict the 36 h IFNαβ production by pDC, resulting in enhanced survival of cDC which promotes increased numbers of MCMV-specific CD8T-cells at day 4 in the spleen. Cross-talk between Ly49H+ NK cells and CD8α DC maintains the numbers of both these cells, and involves DC-derived IL-12 and IL-18 (blue inset) [136]. Infection of Perforin-deficient mice (blue inset) results in lethal immunopathology mediated by CD11b+ F4/80+ and CD4+ cells secreting TNFα. IL-10, likely secreted by Ly49H+ NK cells, dampens immunopathogenic MCMV-specific CD8 T-cell responses that develop in Perforin−/− mice [123]. NK cells are also activated in Ly49H− mice at 36 h (bottom), but in spite of producing IFNγ and TNFα they control viral spread considerably worse than Ly49H+ NK cells. Consequently, substantially higher levels of IFNαβ is produced by pDC at 36h in Ly49H− mice (low MCMV dose), promoting enhanced death of cDC and a 1 day delay in the priming/expansion of MCMV-specific CD8 T-cells [116]. (b) MCMV m157 interactswith the activating receptor Ly49H on NK cells, resulting in their proliferation and acquisition of effector functions. The cell surface expression of the NKG2D ligands RAE-1, H60 and MULT-1 are restricted by theMCMV proteins m138, m152 and m145 which induce their degradation in infected cells. The mechanism by which the MHCI-homologous protein m144 dampens NK control is unknown. The MCMV m04 protein complexes with H-2Dk and binds the Ly49P NK-activating receptor. MCMV m166 binds TRAIL-R2 and restricts its cell surface expression. Cross-talk between NK cells and CD11b+ DC occurs via NKG2D-NKG2D-L interactions, and in concert with IFNαβ induces enhanced NK cell cytotoxicity. DC-derived IL-12 and IL-18 promote IFNγ production by the NK cells (blue inset).

The IFNαβ response upon HCMV infection of DC

The ability of HCMV to infect DC subsets has been examined by many groups, including pDC, myeloid-DC (mDC, both from human blood and GM-CSF/IL-4 derived) and Langerhans-like DC. Much of this work has been focused on how HCMV alters the ability of these cells to prime/activate T-cells, as this is amajor function of DC, and this aspect has been recently reviewed [102]. In general, this work has shown that mDC and Langerhans-like DC can be infected in culture with ‘clinical isolates’ of HCMV at high MOI, resulting in the decreased expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules which then restricts the allogeneic activation of co-cultured T-cells [103-108]. Importantly, this inhibition requires productive HCMV replication within the antigen presenting cell (APC), allowing for expression/function of viral immune modulatory genes. In more recent studies, where pDC isolated from peripheral blood have been infected with HCMV, efficient productive infection has not been observed [108-111]. However, these pDC still produce large amounts of IFNαβ when exposed to HCMV particles, likely through a TLR7 or TLR9-dependent pathway [110], and very little IL-12 is produced concurrently. The production of innate cytokines by HCMV-exposed pDC, in combination with the inability of the virusto replicate in these cells, is consistent with what has been observed in vivo for MCMV and pDC [68]. Interestingly, pDC exposed to HCMV display a compromised ability to activate B, T or NK cells [110, 111], suggesting HCMV may alter pDC functions even when it cannot replicate efficiently in these cells. Finally, adding further complexity to the story, if human pDC are isolated from tonsil tissue as opposed to peripheral blood, HCMV infects these cells efficiently, restricts their ability to produce IFNαβ and inhibits expression of MHC and cosignalling molecules [112]. Taken together, it seems the field is only beginning to grasp what role specific subsets of human pDC might play in the context of HCMV infection. Notably, as chronic viral infections in mice can result in the ‘exhaustion’ of pDC function [113], it is intriguing to speculate that reactivation of HCMV during immune suppression may cause a similar problem, and this possibility has been recently discussed[114].

Transitioning from innate to adaptive immunity during CMV infection

Up to this point, we have focused almost entirely upon the timing of innate defense mechanisms that control CMV infection during the first few days. However, the development of adaptive immunity is needed to ultimately control primary CMV infection. Furthermore, sustained adaptive immunity is crucial in maintaining long-term control of CMV, highlighted by the fact that CMV reactivates and causes serious clinical problems in patients who are immune suppressed. We will now discuss how the robust innate defenses operable during primary MCMV infection can help to promote the development of adaptive immunity. In very general terms, as MCMV-induced innate cytokines (e.g. IFNαβ and TNF) can promote upregulation of MHC and cosignalling ligands on bystander APC, this represents a link between innate and adaptive immunity that is conserved amongst most pathogens [115]. As most of the key cellular immune players are not productively infected by CMV (e.g. NK, iNKT, T and B cells), this limits CMVs ability to modulate these responses to two general strategies: (i) altering their function by infecting/modulating the cells they interact with (e.g. infection of myeloid lineage or stromal cells) or (ii) promoting the secretion of host or viral cytokines/chemokines that can act upon these cells.

The relationship between virus ‘load’, IFNαβ production and CMV-specific adaptive immunity

The functional consequences of IFNαβ signalling can vary greatly depending upon the relative amount produced, with low levels often being immune stimulatory and higher levels capable of promoting immune suppression. The role that varying levels of IFNαβ production play in promoting the development of MCMV-specific T-cell responses has been examined in mice containing or lacking Ly49H-expressing NK cells [116]. When infecting Ly49H-mice with modest doses of MCMV (5 × 103 pfu), splenic pDC produced high levels of IFNαβ at 36 h in response to the first round of MCMV spread, not unexpectedly based on previously published work. However, when Ly49H+ mice were infected with the same low MCMV dose, splenic pDC did not produce IFNαβ. Importantly, if 5-fold more MCMV was injected, splenic pDC from both Ly49H+ and Ly49H− mice produced high amounts of IFNαβ. This highlights the fact that critical ‘thresholds’ exist in genetically distinct mouse strains, and these must be considered when comparing MCMV-specific innate immune responses (reviewed in [65]). Subsequently, the authors observed that the maintenance of cDC numbers in the spleen correlated with the production of IFNαβ by the pDC, with Ly49H+ mice maintaining 2–3-fold higher numbers of cDC at day 2–3 after infection. Consequently, when the numbers of MCMV-specific CD8 T-cells were examined in the spleen at day 4 after infection of Ly49H+ mice, ~5–10-fold higher numbers were seen in comparison with Ly49H− mice (Fig. 2). However, 1 day later, MCMV-specific CD8 T-cell numbers in Ly49H− mice achieved similar levels to that seen in Ly49H+ mice, suggesting that the ‘advantage’ gained by maintaining cDC numbers and accelerating the development of pathogen-specific adaptive immunity is rather short lived, at least in this system. Nevertheless, this work revealed that when CMV infection approaches specific threshold levels of innate immune control, which undoubtedly exist in the polymorphic human population, significant differences in the overall shape of innate and adaptive immunity can result. Interestingly, at very high doses of MCMV infection in Ly49H+ mice, IFNαβ promotes the survival of splenic cDC at day 2–3 [29], highlighting the complexity of these different thresholds.

What are other possible consequences of high levels of early IFNαβ in MCMV infection? In the LCMV model, NK cells exposed to high IFNαβ levels are unable to produce IFN-γ, an effect not described for MCMV infection [117, 118]. LCMV infection can also induce a transient lymphopenia caused by IFNαβ-mediated attrition of memory and ‘memory phenotype’ (CD44 high) CD8 T-cells [119-121]. In turn, IFNα can desensitize naïve CD8 T-cells to IL-2, IL-7 and IL-15-induced proliferation [118], altering the development of LCMV-specific T-cell responses. However, it is currently not known whether similar effects of IFNαβ might be operable during CMV infection.

Perforin-deficient mice reveal roles for NK cells in regulating MCMV-specific adaptive immunity

In addition to potentially promoting MCMV-specific adaptive immunity by regulating IFNαβ-dependent cDC survival, a second function for NK cells in regulating adaptive immunity has been revealed by infecting perforin−/− mice with MCMV (Perf−/−) [87, 122, 123]. Perf−/−) mice cannot control acute MCMV replication and succumb to infection in ~1 week, displaying excessive levels of TNF and IFNγ in the serum and severe immunopathology in the liver. In Ly49H+ mice, CD11b+ myeloid cells (DC and macrophages) produce the majority of the detrimental TNF, with some contribution by CD4 T-cells. The increased levels of systemic IFNγ production were found to be due to the expansion of specific NK subsets and MCMV-specific CD8 T-cells [123]. Perf−/− mice show a preferential proliferation and expansion of Ly49H+ NK cells, with more than a 5-fold increase compared to wild-type mice by day 4 after infection [123]. This is almost certainly because Ly49H-expressing NK cells are stimulated by m157 to a higher degree in Perf−/− mice due to increased MCMV replication levels. Notably, these hyperactivated, Ly49H+ NK cells produce IL-10, which in turn limits the expansion/activation of MCMV-specific CD8 T-cells at day 7 of infection. Supporting this model, Ly49H−Perf−/− mice have even higher levels of MCMV-specific CD8 T-cells and lower levels of systemic IL-10, resulting in the death of these mice due to CD8 T-cell-mediated immunopathology. Importantly, this data indicates that direct stimulation of NK cells through an activating receptor (Ly49H in this case) can modulate their proliferation and cytokine production, distinct from roles for these receptors in promoting cytotoxic functions.

NK-DC cross-talk in the promotion of T-cell responses

A positive role for NK cells in promoting adaptive immunity was first suggested in 1987 [124]. NK cells have a unique capability to further activate DC when suboptimal levels of ‘danger signals’ are present, a function that is especially important for the elicitation of immune responses against tumours [125-128]. NK-DC cross-talk requires NK-derived cytokines (TNFα/IFN-γ) and cell–cell contact, although the specific cell surface molecules are currently uncharacterized [125, 129]. In various experimental systems, including CMV, the operable DC-derived cytokines promoting IFNγ production by NK cells are IL-12 and IL-18 [68, 130, 131], whilst IFNαβ, IL-2 and IL-15 regulate NK cytotoxicity and proliferation [68, 130-135]. During MCMV infection, Ly49H+ NK cells maintain the numbers of CD8α+ cDC in the spleen of B6 mice at day 4–6 of infection [136]. When Ly49H+ NK cells are depleted, CD8α+ cDC numbers decrease dramatically at day 4, but MCMV replication also increases concurrently by ~100-fold. Consequently, it is somewhat difficult to separate the relative roles that cross-talk and restriction of MCMV replication mediated by Ly49H+ NK cells have in protecting this splenic cDC population. However, there does appear to be some selectivity for CD8α+ cDC in regulating the Ly49H+ NK population, as expansion of Ly49H+ but not Ly49G+ NK cells requires their presence, in combination with IL-12 and IL-18 [136]. Consistent with this selectivity, Ly49H+ NK cells proliferate and acquire effector functions during MCMV infection in the absence of IL-15 [137], suggesting that the m157-Ly49H interaction can functionally substitute for host pathways that normally regulate NK cell differentiation and function. Finally, previously discussed results indicated that NK-DC cross-talk via NKG2D-NKG2DL contributes to NK acquisition of cytotoxicity [73].

Taken together, the use of Ly49H+ and Ly49H− mouse strains has revealed that NK cells have the capacity to regulate the development of MCMV-specific CD8 T-cell responses through both direct and indirect mechanisms. The challenge(s) moving forward are to determine the mechanisms by which NK cells can shape CMV-specific adaptive immunity in the absence of a dominant, Ly49H-like NK cell response. This was revealed to some degree in the studies using Ly49H−/−Perf−/− mice [123], but of course using mice deficient in a major component of innate defense also has some drawbacks. Other work outside the CMV field has elucidated additional ‘adaptive’ functions for NK cells. NK cell ‘helper’ functions mediated by skewing CD4 T-cell differentiation towards a Th1 phenotype, NK memory-like responses and finally Th17-like NK cells (NK-22’s) are a few specific examples of this [137-146]. These observations suggest that the diverse populations of NK cells which clearly play a role in regulating CMV infection may play additional, currently unappreciated roles in shaping theCMV-specific adaptive response.

The role of IFNαβ and chemokines in the sequential recruitment of NK and CD8 T-cells to the liver during MCMV infection

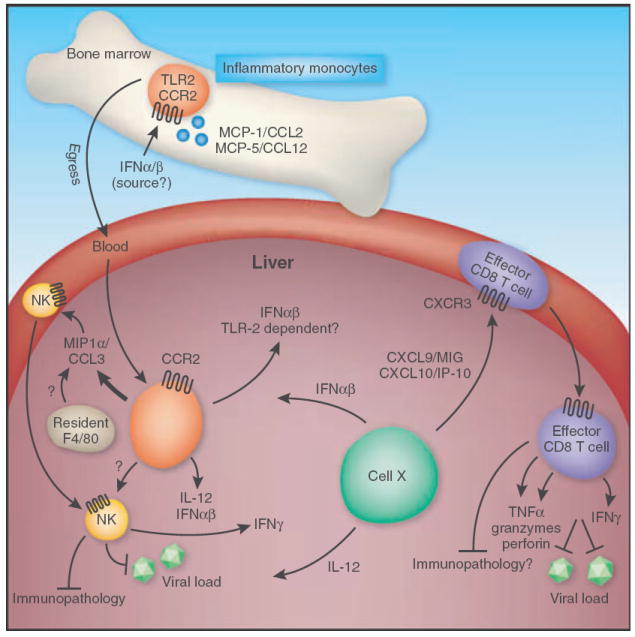

An elegant series of papers from the groups of Biron and Salazar-Mather over the last decade have elucidated the role that innate cytokines and chemokines play in regulating the sequential recruitment of innate cell populations to the liver duringMCMV infection (Fig. 3). MyD88-dependent, IFNαβ production by a Ly6G/C expressing cell in the liver (discussed above [84]), in combination with IFNαβ signalling in the BM, promotes induction of CCR2 ligands (MCP-1/CCL2 and MCP-5/CCL12) by F4/80+ myeloid cells. These CCR2 ligands are required for egress of inflammatory monocytes from the BM into the blood and their subsequent entry into the liver, where they then produce MIP-1α/CCL3 and promote the recruitment of NK cells [147, 148]. These liver-recruited NK cells then acquire effector functions in response to locally produced IFNαβ and IL-12, and function to restrict MCMV spread. In turn, NK-produced IFNγ induces production of CXCR3-ligands in the liver, promoting the recruitment of naïve CD8 T-cells which are primed by MCMV antigens, expand and acquire effector functions [149]. Importantly, both human and mouse CMV encode their own viral chemokines and chemokine receptors which have been shown to regulate various aspects of acute and persistent replication and dissemination, and this has been reviewed recently in detail elsewhere [150].

Fig. 3.

Innate MCMV defenses in the liver promote the development of adaptive immunity. IFN-α/β signalling is required for the induction of CCR2 ligands in the bone marrow(BM) (MCP-1/CCL2 and MCP-5/CCL12). Upon CCR2 signalling, inflammatory macrophages egress from the bone marrow into the blood and infiltrate the liver. MIP1α/CCL3 produced by these inflammatory monocytes/macrophages, potentially in combination with production by liver-resident F4/80+ macrophages, recruits NK cells from the blood into the liver. NK cells are then activated in response to IFN-α/b and IL-12, potentially produced via a TLR2-dependent mechanism by inflammatory monocytes or by a currently unknown cell ‘X’ via a TLR9-independent, MyD88-dependent mechanism. Activated NK cells can then function to control MCMV spreadin the liver. In turn, NK-produced IFN-γ induces expression ofCXCR3-ligands (CXCL9 and CXCL10) by cell ‘X’, promoting the recruitment of MCMV-specific CD8T-cells from the blood, which function to further restrict MCMV replication and may also promote immune pathology in some settings. Effect or CD8T-cells induced by these cytokines and chemokines secrete IFN-γ and TNF. Furthermore, they are loaded with cytolytic granules containing granzyme and perforin.

CMV-modulation of T-cell priming

As already discussed, direct infection of APC by CMV results in profound phenotypic and functional alterations in these cells, including the restriction of MHC expression [151] and inhibition of co-stimulatory molecules, and has been the topic of several excellent recent reviews [102,152]. These alterations have dramatic consequences on the priming of naïve CD8 and CD4 T-cells [153], and MCMV was originally said to promote a ‘paralysed’ phenotype in infected DC [154]. However, unless experiments are designed to analyse relatively pure populations of CMV-infected DC, in the absence of ‘contaminating’ uninfected APC, interpreting the outcome of CMV immune modulation on T-cell responses is complicated. Notably, MCMV productively infects only a small fraction of the cDC subsets in vivo in B6 mice, even at times of peak acute replication [68], thereby subjecting only a fraction of APC to direct immune modulation by the virus. However, the remaining uninfected APC mature in response to bystander cytokine production (e.g. IFNαβ), which promotes efficient cross-presentation of viral antigens [155] and subsequent priming of MCMV-specific CD8 T-cell responses [156]. This model would explain why direct infection of mice with an MCMV mutant unable to modulate expression of MHCI expression produced no differences in the immunodominance hierarchy or magnitude of the MCMV-specific CD8T-cell response [157].

To attempt and address this issue, one study utilized a B6 mouse strain containing a mutation in the H-2Kb MHC molecule (Kbm1) to dissect the relative effects that priming naïve T-cells by infected or uninfected DC can have on shaping the MCMV-specific CD8 T-cell response [156]. Interestingly, these studies revealed that naïve T-cells encountering a DC directly infected withMCMVare highly subject to negative cosignalling mediated by PD-L1/PD-1 interactions, and that this interaction could account for a large percentage of the T-cell ‘stunting’ or ‘paralysis’ seen by several groups. Again consistent with a model where the majority of MCMV-specific CD8 T-cells are cross-primed by uninfected APC in vivo, administration of a blocking anti-PD-L1 antibody barely altered the profile of this response in wild-type mice infected with MCMV. This was in stark contrast to the dramatic restoration of T-cell proliferation and effector function(both in vitro and in vivo) that was observed when PD-L1 was blocked in an experimental setup where naïve T-cells could only primed by DC thatwere productively infected with MCMV [156].

The CMV-specific memory T-cell pool

The nature of the CMV-specific memory T-cell pool has garnered significant attention, as HCMV infection is coincident with every known case of a severe immunosenescence phenotype in old individuals referred to as the immune risk profile (IRP). IRP develops in persons >80 years old, where the circulating CD4: CD8 T-cell ratio inverts (i.e. CD4: CD8 <1) and is predictive of decreased immune function and poor patient survival [158]. The gradual increase (or maintenance) of the numbers of CMV-specific memory T-cells over the many decades of persistent infection is largely unique to this virus (termed ‘memory inflation’ [159]), and has been postulated to play a role in promoting the IRP. HCMV-specific T-cells can reach strikingly high numbers in select older individuals (>45%has been documented), but normally comprise ~10–20% of the pool [160, 161]. This large, diverse CMV-specific T-cell memory pool is also seen during rhesus CMV infection [162]. The inflationary, MCMV-specific memory responses appear to be analogous to the oligoclonal expansion of HCMV-specific CD8 T-cells seen in people (reviewed in [163]). MCMV-specific inflationary CD8 T-cells display an effector-memory phenotype, suggesting they may have recently reencountered antigen [164-166]. This would be consistent with observations that MCMV production from the salivary gland (SG) is detectable at late times after primary infection (>100 days), but occurs in a sporadic, semi-random manner and varies based on the strain of virus and mice (A. Loewendorf, personal observation). Interestingly, the recent characterization of MCMV epitope-specific CD4 T-cell responses revealed that they also can vary greatly with respect to their kinetics of expansion and contraction [167]. Although some progress has been made towards understanding the mechanisms underlying memory inflation [168, 169], there is still much to be learned.

Continued CMV shaping of adaptive immunity during persistence/latency

Several elegant studies from Reddehase et al. have indicated that low-level, sporadic MCMV reactivation from latency in the lung of Balb/c mice contributes to the inflation of memory CD8 T-cells specific for an epitope derived from the IE1-protein [170]. However, as these same CD8 T-cells restrict further reactivation of MCMV gene expression, this does not explain how CD8 T-cells specific for nonIE antigens also inflate in Balb/c and B6 mice. Presumably, there is a tissue site of MCMV reactivation, or chronic persistence, which functions as an antigen source and promotes the maintenance/expansion of CMV-specific T-cells. The SG is an immune-privileged, mucosal organ that is a potential candidate for this site. Interestingly, HCMV can shed for years from the SG of infected children [171], and rhesus CMV may shed for life from the SG [172]. In mice, immune control of MCMV in the SG is quite unique, and includes an immune suppressive role for IL-10 and a strict requirement for CD4 T-cells [173-175]. Strikingly, the HCMV IL-10 orthologue is the only gene known to be expressed during latent infection of myeloid precursor cells [176]. Interestingly, NK cells can promote DC function and T-cell priming under suboptimal conditions of trying to mount effective anti-tumour immunity [125-128]. As NK cells may contribute to control MCMV replication at early time-points in the SG [87], this may represent another link between innate and adaptive immune responses operable during persistent CMV replicationin the SG.

Conclusions

We have attempted to paint a chronological picture of how anti-CMV immune defenses fit together to combat and control CMV infection. In turn, we have discussed a number of the known CMV immune modulating strategies, and have attempted to present them in the context of when we feel they are most likely to have the greatest effect(s) on shaping host defenses. As CMV infects >50% of the worlds population, and a high priority for the scientific community is the development of an anti-CMV vaccine for use in combating congenital infection [177], we hope that this review will allow for easier conceptualization of what is needed to accomplish this goal.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to our colleagues in the field whose work we could not reference due to lack of space. This work was supported in part by grants AI076864 and AI069298 from the NIH to C.A.B.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement No conflict of interest was declared.

References

- 1.McGeoch DJ, Dolan A, Ralph AC. Toward a comprehensive phylogeny for mammalian and avian herpesviruses. J Virol. 2000;74:10401–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10401-10406.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pereira L, Maidji E, McDonagh S, Tabata T. Insights into viral transmission at the uterine-placental interface. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:164–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redpath S, Angulo A, Gascoigne NR, Ghazal P. Immune checkpoints in viral latency. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:531–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarvis M, Nelson J. Human cytomegalovirus persistence and latency in endothelial cells and macrophages. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:403. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Streblow DN, Dumortier J, Moses AV, Orloff SL, Nelson JA. Mechanisms of cytomegalovirus-accelerated vascular disease: induction of paracrine factors that promote angiogenesis and wound healing. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:397–415. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soderberg-Naucler C. Does cytomegalovirus play a causative role in the development of various inflammatory diseases and cancer? J Intern Med. 2006;259:219–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cobbs CS, Harkins L, Samanta M, et al. Human cytomegalovirus infection and expression in human malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3347–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michaelis M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J. The story of human cytomegalovirus and cancer: increasing evidence and open questions. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1–9. doi: 10.1593/neo.81178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JM, Kaneshima H, Mocarski ES. Dramatic interstrain differences in the replication of human cytomegalovirus in SCID-humice. J Infect Dis. 1996;171:1599–603. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W, Taylor SL, Leisenfelder SA, et al. Human cytomegalovirus genes in the15-kilobase region are required for viral replication in implanted human tissues in SCID mice. J Virol. 2005;79:2115–23. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2115-2123.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy E, Yu D, Grimwood J, et al. Coding potential of laboratory and clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14976–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136652100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brocchieri L, Kledal TN, Karlin S, Mocarski ES. Predicting coding potential from genome sequence: application to betaherpesviruses infecting rats and mice. JVirol. 2005;79:7570–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7570-7596.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beutler B, Georgel P, Rutschmann S, Jiang Z, Croker B, Crozat K. Genetic analysis of innate resistance tomouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2005;4:203–13. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/4.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scalzo AA, Corbett AJ, Rawlinson WD, Scott GM, Degli-Esposti MA. The interplay between host and viral factors in shaping the outcome of cytomegalovirus infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:46–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenac T, Arapovic J, Traven L, Krmpotic A, Jonjic S. Murine cytomegalovirus regulation of NKG2D ligands. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2008;197:159–66. doi: 10.1007/s00430-008-0080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeFilippis VR. Induction and evasion of the type I interferon response by cytomegaloviruses. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;598:309–24. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-71767-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biron CA, Byron KS, Sullivan JL. Severe herpesvirus infections in an adolescent without natural killer cells. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1731–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906293202605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Issacs A, Lindemann J. Virus interference: the interferons. Prog Roy Soc Biol (Lond) 1957;147:258–73. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osborn JE, Medearis DN., Jr Studies of relationship between mouse cytomegalovirus and interferon. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1966;121:819–24. doi: 10.3181/00379727-121-30897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oie HK, Easton JM, Ablashi DV, Baron S. Murine cytomegalovirus: induction of and sensitivity to interferon in vitro. Infect Immun. 1975;12:1012–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.12.5.1012-1017.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kern ER, Olsen GA, Overall JC, Jr, Glasgow LA. Treatment of a murine cytomegalovirus infection with exogenous interferon, polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid, and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid-poly-L-lysine complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;13:344–6. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.2.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grundy JE, Trapman J, Allan JE, Shellam GR, Melief CJ. Evidence for a protective role of interferon in resistance to murine cytomegalovirus and its control bynon-H-2-linked genes. Infect Immun. 1982;37:143–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.1.143-150.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong KT, Gresser I, Mims CA. Interferon as a defence mechanism in mouse cytomegalovirus infection. J Gen Virol. 1983;64(Pt 2):461–4. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-2-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinnan GV, Manischewitz JE. The role of natural killer cells and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Exp Med. 1979;150:1549–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.6.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shellam GR, Allan JE, Papadimitriou JM, Bancroft GJ. Increased susceptibility to cytomegalovirus infectionin beige mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:5104–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bukowski JF, Warner JF, Dennert G, Welsh RM. Adoptive transfer studies demonstrating the antiviral effect of natural killer cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 1985;161:40–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bukowski JF, Woda BA, Welsh RM. Pathogenesis of murine cytomegalovirus infection in natural killer cell-depleted mice. J Virol. 1984;52:119–28. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.1.119-128.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider K, Loewendorf A, De Trez C, et al. Lymphotoxin-mediated crosstalk between B cells and splenic stroma promotes the initial type I interferon response to cytomegalovirus. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banks TA, Rickert S, Benedict CA, et al. A lymphotoxin-IFN-beta axis essential for lymphocyte survival revealed during cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:7217–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu KM, Pratt JR, Akers WJ, Achilefu SI, Yokoyama WM. Murine cytomegalovirus displays selective infection of cells within hours after systemic administration. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:33–43. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.006668-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orange JS, Wang B, Terhorst C, Biron CA. Requirement for natural killer cell-produced interferon gamma in defense against murine cytomegalovirus infection and enhancement of this defense pathway by interleukin 12 administration. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1045–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orange JS, Biron CA. Characterization of early IL-12, IFN-alpha beta, and TNF effects on antiviral state and NK cell responses during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:4746–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biron CA. Initial and innate responses to viral infections – pattern setting in immunity or disease. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:374–81. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tyznik AJ, Tupin E, Nagarajan NA, Her MJ, Benedict CA, Kronenberg M. Cutting edge: the mechanism of invariant NKT cell responses to viral danger signals. J Immunol. 2008;181:4452–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raftery MJ, Hitzler M, Winau F, et al. Inhibition of CD1 antigen presentation by human cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 2008;82:4308–19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01447-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benedict CA, Banks TA, Senderowicz L, et al. Lymphotoxins and cytomegalovirus cooperatively induce interferon-beta, establishing host-virus detente. Immunity. 2001;15:617–26. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iversen AC, Norris PS, Ware CF, Benedict CA. Human NK cells inhibit cytomegalovirus replication through a noncytolytic mechanism involving lymphotoxin-dependent induction of IFN-beta. J Immunol. 2005;175:7568–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thanos D, Maniatis T. Virus induction of human IFN beta gene expression requires the assembly of an enhanceosome. Cell. 1995;83:1091–100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maniatis T, Falvo JV, Kim TH, et al. Structure and function of the interferon-beta enhanceosome. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:609–20. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eickhoff J, Hanke M, Stein-Gerlach M, et al. RICK activates a NF-kappaB-dependent anti-human cytomegalovirus response. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9642–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Randolph-Habecker J, Iwata M, Geballe AP, Jarrahian S, Torok-Storb B. Interleukin-1-mediated inhibition of cytomegalovirus replication is due to increased IFN-beta production. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:765–72. doi: 10.1089/107999002320271350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shinkura R, Kitada K, Matsuda F, et al. Alymphoplasia is caused by a point mutation in the mouse gene encoding Nf-kappa b-inducing kinase. Nat Genet. 1999;22:74–7. doi: 10.1038/8780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:606–16. doi: 10.1038/nri1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Browne EP, Wing B, Coleman D, Shenk T. Altered cellular mRNA levels in human cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts: viral block to the accumulation of antiviral mRNAs. J Virol. 2001;75:12319–30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12319-12330.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor RT, Bresnahan WA. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 2 gene expression blocks virus-induced beta interferon production. J Virol. 2005;79:3873–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3873-3877.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor RT, Bresnahan WA. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 2 protein IE86 blocks virus-induced chemokine expression. J Virol. 2006;80:920–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.920-928.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montag C, Wagner J, Gruska I, Hagemeier C. Human cytomegalovirus blocks tumor necrosis factor alpha- and interleukin-1 beta-mediated NF-kappaB signaling. J Virol. 2006;80:11686–98. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01168-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jarvis MA, Borton JA, Keech AM, et al. Human cytomegalovirus attenuates interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha proinflammatory signaling by inhibition of NF-kappaB activation. J Virol. 2006;80:5588–98. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00060-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baillie J, Sahlender DA, Sinclair JH. Human cytomegalovirus infection inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) signaling by targeting the 55-kilodalton TNF-alpha receptor. J Virol. 2003;77:7007–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.7007-7016.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Popkin DL, Virgin HWt. Murine cytomegalovirus infection inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha responses in primary macrophages. J Virol. 2003;77:10125–30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.10125-10130.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le VT, Trilling M, Zimmermann A, Hengel H. Mouse cytomegalovirus inhibits beta interferon (IFN-beta) gene expression and controls activation pathways of the IFN-beta enhanceosome. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:1131–41. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83538-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sato M, Hata N, Asagiri M, Nakaya T, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N. Positive feedback regulation of type I IFN genes by the IFN-inducible transcription factor IRF-7. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:106–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zimmermann A, Trilling M, Wagner M, et al. A cytomegaloviral protein reveals a dual role for STAT2 in IFN-{gamma} signaling and antiviral responses. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1543–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marshall EE, Geballe AP. Multifaceted evasion of the interferon response by cytomegalovirus. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:609–19. doi: 10.1089/jir.2009.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCormick AL. Control of apoptosis by human cytomegalovirus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:281–95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalejta RF. Functions of human cytomegalovirus tegument proteins prior to immediate early gene expression. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:101–15. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andoniou CE, Degli-Esposti MA. Insights into the mechanisms of CMV-mediated interference with cellular apoptosis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Declercq W, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. RIP kinases at the crossroads of cell death and survival. Cell. 2009;138:229–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mack C, Sickmann A, Lembo D, Brune W. Inhibition of proinflammatory and innate immune signaling pathways by a cytomegalovirus RIP1-interacting protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3094–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. Cytomegalovirus M45 cell death suppression requires receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homotypic interaction motif (RHIM)-dependent interaction with RIP1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16966–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800051200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rebsamen M, Heinz LX, Meylan E, et al. DAI/ZBP1 recruits RIP1 and RIP3 through RIP homotypic interaction motifs to activate NF-kappaB. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:916–22. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brune W, Menard C, Heesemann J, Koszinowski UH. A ribonucleotide reductase homolog of cytomegalovirus and endothelial cell tropism. Science. 2001;291:303–5. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takaoka A, Wang Z, Choi MK, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007;448:501–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeFilippis V, Alvarado D, Rothenburg S, Fruh K. Abstract (2.04): Human Cytomegalovirus Induces the Interferon Response via the DNA Receptor ZBP1. Ithaca, NY: International Herpesvirus Workshop; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pyzik M, Kielczewska A, Vidal SM. NK cell receptors and their MHC class I ligands in host response to cytomegalovirus: insights from the mouse genome. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:331–42. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scalzo AA, Yokoyama WM. Cmv1 and natural killer cell responses to murine cytomegalovirus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;321:101–22. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75203-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dalod M, Salazar-Mather TP, Malmgaard L, et al. Interferon alpha/beta and interleukin 12 responses to viral infections: pathways regulating dendritic cell cytokine expression in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;195:517–28. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dalod M, Hamilton T, Salomon R, et al. Dendritic cell responses to early murine cytomegalovirus infection: subset functional specialization and differential regulation by interferon alpha/beta. J Exp Med. 2003;197:885–98. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Krug A, French AR, Barchet W, et al. TLR9-dependent recognition of MCMV by IPC and DC generates coordinated cytokine responses that activate antiviral NK cell function. Immunity. 2004;21:107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zucchini N, Bessou G, Robbins SH, et al. Individual plasmacytoid dendritic cells are major contributors to the production of multiple innate cytokines in an organ-specific manner during viral infection. Int Immunol. 2008;20:45–56. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akira S. TLR signaling. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;311:1–16. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tabeta K, Georgel P, Janssen E, et al. Toll-like receptors 9 and 3 as essential components of innate immune defense against mouse cytomegalovirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3516–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400525101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andoniou CE, van Dommelen SL, Voigt V, et al. Interaction between conventional dendritic cells and natural killer cells is integral to the activation of effective antiviral immunity. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1011–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Delale T, Paquin A, Asselin-Paturel C, et al. MyD88-dependent and -independent murine cytomegalovirus sensing for IFN-alpha release and initiation of immune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175:6723–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zucchini N, Bessou G, Traub S, et al. Cutting edge: overlapping functions of TLR7 and TLR9 for innate defense against a herpesvirus infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:5799–803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brinkmann MM, Spooner E, Hoebe K, Beutler B, Ploegh HL, Kim YM. The interaction between the ER membrane protein UNC93B and TLR3, 7, and 9 is crucial for TLR signaling. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:265–75. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tabeta K, Hoebe K, Janssen EM, et al. The Unc93b1 mutation 3d disrupts exogenous antigen presentation and signaling via Toll-like receptors 3, 7 and 9. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:156–64. doi: 10.1038/ni1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoebe K, Du X, Georgel P, et al. Identification of Lps2 as a key transducer of MyD88-independent TIR signalling. Nature. 2003;424:743–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoebe K, Janssen EM, Kim SO, et al. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules induced by lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA occurs by Trif-dependent and Trif-independent pathways. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1223–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Liang X, Welsh RM, Kurt-Jones EA, Finberg RW. Role for TLR2 in NK cell-mediated control of murine cytomegalovirus in vivo. J Virol. 2006;80:4286–91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4286-4291.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barbalat R, Lau L, Locksley RM, Barton GM. Toll-like receptor 2 on inflammatory monocytes induces type I interferon in response to viral but not bacterial ligands. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1200–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baccala R, Gonzalez-Quintial R, Lawson BR, et al. Sensors of the innate immune system: their mode of action. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:448–56. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]