Abstract

Accurate nuclear identification is crucial for distinguishing the role of cardiac myocytes in intrinsic and experimentally induced regenerative growth of the myocardium. Conventional histologic analysis of myocyte nuclei relies on the optical sectioning capabilities of confocal microscopy in conjunction with immunofluorescent labeling of cytoplasmic proteins such as troponin T, and dyes that bind to double-strand DNA to identify nuclei. Using heart sections from transgenic mice in which the cardiomyocyte-restricted α-cardiac myosin heavy chain promoter targeted the expression of nuclear localized β-galactosidase reporter in >99% of myocytes, we systematically compared the fidelity of conventional myocyte nuclear identification using confocal microscopy, with and without the aid of a membrane marker. The values obtained with these assays were then compared with those obtained with anti-β-galactosidase immune reactivity in the same samples. In addition, we also studied the accuracy of anti-GATA4 immunoreactivity for myocyte nuclear identification. Our results demonstrate that, although these strategies are capable of identifying myocyte nuclei, the level of interobserver agreement and margin of error can compromise accurate identification of rare events, such as cardiomyocyte apoptosis and proliferation. Thus these data indicate that morphometric approaches based on segmentation are justified only if the margin of error for measuring the event in question has been predetermined and deemed to be small and uniform. We also illustrate the value of a transgene-based approach to overcome these intrinsic limitations of identifying myocyte nuclei. This latter approach should prove quite useful when measuring rare events.

Keywords: myocyte nuclear identification, cardiac myocyte-restricted α-cardiac myosin heavy chain promoter β-galactosidase reporter mice, cell membrane marker, cardiomyogenic transcription factor, confocal microscopy

histologic analysis of myocardial regeneration and the pathophysiology of cardiac diseases in many cases rely on scoring events that occur in the myocyte nucleus. Consequently, the accurate identification of myocyte nuclei in histologic sections is vital for quantitative analyses. However, distinguishing between a myocyte and a nonmyocyte nucleus can be difficult. Even though myocytes occupy 70% of myocardial volume, they only contribute to 20–30% of the total nuclei present in the adult mouse heart (14). Given the interest in quantitating intrinsic and experimentally induced regenerative growth of the myocardium (1, 11, 13), accurate nuclear identification is crucial to distinguishing the roles of myocytes from those of surrounding cells.

Conventional approaches to identify myocyte nuclei in heart sections typically rely on the use of immune histologic assays with antibodies recognizing myocyte-restricted structural proteins [such as cardiac myosin heavy chain (MHC), cardiac actin, or troponin isoforms] to identify myocyte cytoplasm, and dyes that bind to double-strand DNA to identify nuclei. Signal can be developed with either chromogenic or fluorescent secondary antibodies followed by light or fluorescence microscopy, respectively. Many studies exploit the optical sectioning capabilities of confocal microscopy (3) in combination with fluorescent readouts to distinguish myocyte and nonmyocyte nuclei in histologic specimens. Although membrane markers such as laminin and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) have been previously used to aid myocyte demarcation and measurement of myocyte dimensions (6, 8), a systematic comparison testing the impact of such combinatorial approaches has not been performed. Furthermore, the use of nuclear transcriptional factors associated with cardiogenesis such as GATA4 to improve myocyte nuclei identification has also not been quantitatively assessed previously.

The ability to readily manipulate the mouse genome (via traditional transgenesis or gene targeting approaches) has facilitated the generation of numerous lines to monitor specific cell lineages using either constitutive or conditional reporter systems. One model utilized the cardiac myocyte-restricted α-cardiac MHC promoter to target expression of a nuclear localized β-galactosidase reporter (MHC-nLAC mice) (12, 15). Analysis of dispersed cell preparations from adult MHC-nLAC hearts revealed that >99% of the myocytes exhibited nuclear β-galactosidase (β-GAL) activity, as evidenced by reacting with X-GAL, a chromogenic β-GAL substrate (15).

In this report, we systematically compared the fidelity of myocyte nuclear identification in MHC-nLAC transgenic heart sections using confocal microscopy in conjunction with anti-troponin T immune histology in the absence and presence of a membrane marker (WGA). The values obtained with these assays were then compared with those obtained with anti-β-GAL immune reactivity in the same samples. We also performed a similar comparison between anti-GATA4 and β-GAL immune reactivity. Our results demonstrate that, although the use of a membrane marker or nuclear transcriptional factor involved in cardiogenesis improves the ability to identify myocyte nuclei in heart sections, there is nonetheless a relatively large error rate despite the use of confocal microscopy.

METHODS

Tissue preparation.

Generation and characterization of the MHC-nLAC transgenic mice was described previously (12, 15). The investigation conformed to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, Revised 1996). The study was approved and the animals received humane care in accordance with the Guidance on the Operation of Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, UK).

The mice were maintained in an inbred DBA/2J genetic background. Hearts from adult MHC-nLAC mice were harvested and fixed in 10% formalin for at least 48 h before paraffin embedding. The resulting blocks were then cut at a thickness of 5 μm using standard protocols (9).

Immunohistochemistry.

Heart sections were deparaffinized in two washes of xylene (5 min each) and rehydrated serially in reducing percentages of Industrial Methylated Spirit solution (100, 90, and 70%), followed by double-distilled water. Forty minutes of microwave antigen retrieval (800 W, full power) in 0.1% EDTA solution was performed. The sections were blocked with 1% BSA for 20 min and then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies overnight.

Anti-β-GAL (ab616, 1:200 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-troponin T (ab33589, 1:200 dilution; Abcam) primary antibodies were used for the study of myocyte identification with and without WGA. Appropriate goat secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) were then incubated overnight at a dilution of 1:200 to detect the primary antibodies. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Molecular Probes catalog no. D1306) and WGA Alexa Fluor 647 nm conjugate (Molecular Probes catalog no. W32466) were used to identify the nucleus and outer cell membrane, respectively.

For the comparison of GATA4 and β-GAL immune reactivity, the heart tissues were stained using the above techniques except that the primary antibodies used were anti-β-GAL (ab9361, 1:200 dilution) and anti-GATA4 (sc-9053; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy and image acquisition.

All image volumes were acquired with an Apocromat ×63 oil immersion Leica lens (numerical aperture of 1.4) at ×1 zoom, using a Leica Confocal SP5 system (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Pinhole diameter was set to 1 Airy unit. Each image volume was a Z-axis stack comprising 42 steps at intervals of 0.24 μm with an X-Y dimension of 246 × 246 × 10.08 μm (although the blocks were sectioned at 5 μm, thickness increased following hydration).

For the study of the accuracy of myocyte identification with and without WGA, a total of 10 image volumes were acquired, of which 5 contained myocytes aligned predominantly in the transverse orientation relative to the X-Y axis and 5 contained myocytes aligned predominantly in the longitudinal orientation relative to the X-Y axis. For each image volume, four-channel Z-stack scans were acquired using line sequential laser excitation at 405 nm (to detect DAPI, pseudocolored blue), 488 nm (to detect β-GAL immune reactivity, pseudocolored green), 561 nm (to detect troponin T immune or GATA4 reactivity, pseudocolored red), and 633 nm (to detect WGA conjugate, pseudocolored white).

To test the ability of immune histology to identify myocyte nuclei in the image volumes, the percentage of β-GAL immune reactive nuclei in sections containing myocytes aligned predominately in the longitudinal orientation was compared with the percentage of nuclei exhibiting X-GAL reactivity in sections with myocytes in a similar alignment. The X-GAL reaction protocol was previously optimized to identify all β-GAL positive nuclei within a section (15). The values obtained via β-GAL immune reactivity and X-GAL reaction were not significantly different (20.6 ± 6 vs. 20.3 ± 5%, respectively; mean ± SE, n = 760 cells), indicating that the immune assay was equally efficient at identifying myocyte nuclei in histologic sections. There was no β-GAL immune reactivity detected in wild-type hearts.

Manual segmentation for scoring nuclear identity with and without WGA.

Leica AF software was utilized in postacquisition mode to generate Z-stacks of the 10 image volumes containing β-GAL, troponin T, DAPI, and WGA. For each image volume, β-GAL myocyte nuclei signals were turned off to generate a two-channel Z-stack (reporting DAPI and troponin T signals only), as well as a separate three-channel Z-stack (reporting DAPI, troponin T, and WGA signals) in “tiff” format. To avoid bias, each Z-stack was then given a coded number and selected in a random order for nuclear identification by different observers. The image sets were imported into Volocity LE (Improvision, Coventry, UK) for the visualization of different layers of the Z-stacks as well as the generation of orthogonal views. To optimize the identification of myocyte nuclei, all available views were used, namely, all layers of the Z-stack, the maximal projection view, and the orthogonal views. A hardcopy of the maximal projection from each two-channel and three-channel Z-stack was printed for the observers involved to mark the position of those nuclei that they identified as myocyte nuclei (that is, nuclei residing within troponin T-positive cytoplasm) without and with the aid of WGA. These results were then compared with the four-channel Z-stack images (that is, images in which DAPI, troponin T, WGA, and β-GAL myocyte nuclear signals were activated; see Fig. 1, C and F, for representative examples) to establish the identity of the nucleus as defined in Table 1. The four-channel Z-stack images were only made available at the final analysis.

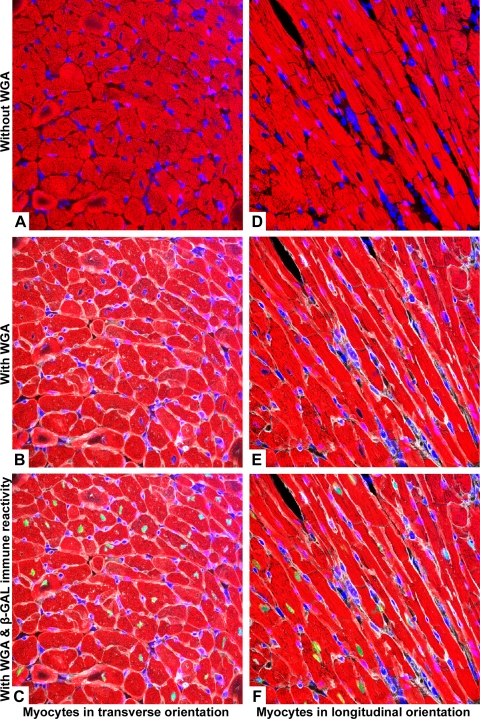

Fig. 1.

Representative maximal projection images used in the study. A–C: images of myocytes predominantly in the transverse orientation. D–F: myocytes orientated predominantly in the longitudinal orientation. Pseudocoloring: red = troponin T, blue = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), white = wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), and green = β-galactosidase (β-GAL) myocyte nucleus.

Table 1.

Definition of terms used to establish the identity of nuclei scored with and without WGA

| β-GAL Immune Reactivity |

||

|---|---|---|

| β-GAL(+) | β-GAL(−) | |

| Myocyte | True positive | False positive |

| Nonmyocyte | False negative | True negative |

Scored nuclear identity is shown. WGA, wheat germ agglutinin; β-GAL, β-galactosidase.

Nuclear identification with GATA4 immune reactivity.

For experiments employing GATA4 immune reactivity, true GATA4 signals were verified by their colocalization with DAPI signals using all available views described above. Only those GATA4 signals that subsequently colocalized with β-GAL nuclear signals were considered true positive. Those true GATA signals without β-GAL nuclear signals were considered nonmyocyte nuclei and false positive.

Statistics.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and diagnostic accuracy were reported as described below. The level of agreement between different observers was calculated using Fleiss kappa (κ) statistics (4).

RESULTS

Image volume characteristics.

Ten image volumes comprising a total of 6,100,012.8 μm3 of ventricular myocardium from MHC-nLAC transgenic hearts were acquired. These volumes contained a total of 1,503 nuclei, of which 292 nuclei showed β-GAL immune reactivity (19.4%). Figure 1 shows the maximal projection for a representative image volume with two channels activated (DAPI and troponin T signals; Fig. 1, A and D), three channels activated (DAPI, troponin T, and WGA signals; Fig. 1, B and E), and four channels activated (DAPI, troponin T, WGA, and β-GAL signals; Fig. 1, C and F).

Overall sensitivity and specificity with and without WGA.

With the use of Table 1, the sensitivity of myocyte nuclear identification is defined mathematically as the no. of true positive nuclei/(the no. of true positive nuclei + the no. of false negative nuclei). Thus a method with a higher sensitivity will be better at identifying nuclei of myocyte origin. The specificity of myocyte nuclear identification is defined mathematically as the no. of true negative nuclei/(the no. of true negative nuclei + the no. of false positive nuclei). Hence, specificity reflects the true negative rate and how good a method is at correctly excluding nonmyocyte nuclei. In the absence of WGA, the overall sensitivity and specificity for all the images ranged from 38 to 48% and 87 to 92%, respectively. With WGA, the sensitivity and specificity improved to 62–68% and to ∼97%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of myocyte nuclei identification

| Sensitivity, % |

Specificity, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation | Observer No. | Without WGA | With WGA | Without WGA | With WGA |

| Transverse | 1 | 45.1 (37.7–52.8) | 64.6 (57.1–71.5) | 90.1 (87.6–92.1) | 98.4 (97.1–99.1) |

| 2 | 48.8 (41.2–56.4) | 68.9 (61.5–75.5) | 89.5 (86.9–91.6) | 99.0 (97.9–99.5) | |

| 3 | 54.3 (46.6–61.7) | 72.6 (65.3–78.8) | 94.4 (92.4–95.9) | 98.4 (97.1–99.1) | |

| Longitudinal | 1 | 28.9 (21.8–37.3) | 59.4 (50.7–67.5) | 83.4 (80.0–86.3) | 94.0 (91.7–95.7) |

| 2 | 34.4 (26.7–43.0) | 56.3 (47.6–64.5) | 84.5 (81.2–87.4) | 95.5 (93.4–97.0) | |

| 3 | 39.8 (31.8–48.5) | 61.7 (53.1–69.7) | 88.5 (85.5–90.9) | 95.3 (93.2–96.8) | |

| Overall | 1 | 38.0 (32.6–43.7) | 62.3 (56.6–67.7) | 87.1 (85.1–88.9) | 96.5 (95.3–97.4) |

| 2 | 42.5 (36.9–48.2) | 63.4 (57.7–68.7) | 87.3 (85.3–89.0) | 97.4 (96.4–98.2) | |

| 3 | 48.0 (42.3–53.7) | 67.8 (62.2–72.9) | 91.7 (90.1–93.2) | 97.0 (95.9–97.8) | |

Units are % with confidence intervals (CI) in parentheses.

Overall positive and negative predictive power with and without WGA.

Positive predictive power is defined mathematically as the no. of true positive nuclei/(the no. of true positive nuclei + the no. of false positive nuclei). It describes the proportion of myocyte nuclei that are correctly identified and reflects the probability of a positive myocyte nuclear identification. On the other hand, the negative predictive power is defined mathematically as the no. of true negative nuclei/(true negative nuclei + the no. of false negative nuclei). Thus a high negative predictive power will indicate that the probability of accurately excluding a nonmyocyte is higher. The use of WGA improved the overall positive predictive power from a range of 42–58% to a range of 85–88%. There was also marginal improvement in the overall negative predictive power from 81–85% without WGA to 91–93% with WGA (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictive power of myocyte nuclei identification in the presence and absence of WGA

| Positive Predictive Power, % |

Negative Predictive Power, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation | Observer No. | Without WGA | With WGA | Without WGA | With WGA |

| Transverse | 1 | 52.5 (44.3–60.5) | 90.6 (83.9–94.7) | 87.1 (84.4–89.4) | 92.0 (89.7–93.7) |

| 2 | 53.0 (45.0–60.8) | 94.2 (88.4–97.1) | 87.8 (85.1–90.0) | 92.9 (90.8–94.6) | |

| 3 | 70.1 (61.6–77.4) | 91.5 (85.5–95.2) | 89.5 (87.0–91.5) | 93.6 (91.6–95.2) | |

| Longitudinal | 1 | 29.4 (22.1–37.8) | 83.1 (79.7–86.0) | 70.4 (61.2–78.2) | 90.7 (88.0–92.8) |

| 2 | 34.7 (26.9–43.3) | 84.4 (81.1–87.2) | 75.0 (65.5–82.6) | 90.2 (87.4–92.3) | |

| 3 | 45.1 (36.3–54.3) | 86.1 (82.9–88.7) | 76.0 (66.9–83.2) | 91.3 (88.6–93.3) | |

| Overall | 1 | 41.6 (35.8–47.6) | 85.4 (83.3–87.2) | 80.9 (75.2–85.5) | 91.4 (89.7–92.8) |

| 2 | 44.6 (38.9–50.5) | 86.3 (84.2–88.1) | 85.7 (80.3–89.7) | 91.7 (90.1–93.1) | |

| 3 | 58.3 (52.0–64.4) | 88.0 (86.1–89.6) | 84.6 (79.4–88.7) | 92.6 (91.0–93.9) | |

Units are % with CI in parentheses.

Overall diagnostic accuracy with and without WGA.

Diagnostic accuracy is defined mathematically as (the no. of true positive nuclei + true negative nuclei)/total nuclei. It describes the proportion of myocyte and nonmyocyte nuclei that are correctly identified. The use of WGA improved the overall diagnostic accuracy from 78–83% to 90–91% (Table 4).

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy of myocyte nuclei identification in the presence and absence of WGA

| Orientation | Observer No. | Diagnostic Accuracy Without WGA, % | Diagnostic Accuracy With WGA, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transverse | 1 | 81.4 (78.6–83.8) | 91.8 (89.7–93.4) |

| 2 | 81.5 (78.7–84.0) | 93.1 (91.2–94.6) | |

| 3 | 86.5 (84.0–88.7) | 93.3 (91.4–94.8) | |

| Longitudinal | 1 | 72.9 (69.4–76.2) | 87.4 (84.6–89.7) |

| 2 | 74.9 (71.5–78.0) | 88.0 (85.3–90.2) | |

| 3 | 79.1 (75.8–82.0) | 88.9 (86.3–91.0) | |

| Overall | 1 | 77.6 (75.4–79.6) | 89.8 (88.2–91.2) |

| 2 | 78.6 (76.4–80.6) | 90.8 (89.3–92.2) | |

| 3 | 83.2 (81.3–85.0) | 91.4 (89.8–92.7) |

Units are % with CI in parentheses.

Impact of myocyte orientation on the identification of myocyte nuclei.

The data above indicate that use of WGA improved the sensitivity and specificity of myocyte nuclear identification (Table 2). However, sensitivity of nuclear identification with or without WGA in myocytes with transverse orientation (without WGA: 45–54%; with WGA: 65–73%) was better than that of myocytes with longitudinal orientation (without WGA: 29–40%; with WGA: 56–62%). In myocytes with transverse orientation, the specificity of myocyte nuclear identification in the presence of WGA was also superior to that of images with myocytes in longitudinal orientation. In terms of predictive power, images with myocytes in the transverse orientation have a higher positive predictive power (53–70%) than those in longitudinal orientation (29–45%) in the absence of WGA. The use of WGA improves this value for myocytes in transverse orientation up to 94%. The negative predictive power and diagnostic accuracy of images with predominantly transverse myocytes are slightly better than those orientated longitudinally both in the presence and absence of WGA (Tables 3 and 4).

Interobserver variability with and without WGA.

The percentage of β-GAL nuclei identified by all three observers was higher when WGA was used (Table 5). Without WGA, more β-GAL nuclei were missed by all three observers. The interobserver agreement was also better with WGA, although Fleiss κ values for both methods (WGA 0.592 vs. without WGA 0.466) suggested, at best, moderate agreement (7) between observers.

Table 5.

Interobserver agreements in the presence and absence of WGA

| Without WGA |

With WGA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| No. of β-GAL nuclei that were not identified | 108 | 37.0 | 67 | 22.9 |

| No. of β-GAL nuclei that were identified by 1 observer | 56 | 19.2 | 30 | 10.3 |

| No. of β-GAL nuclei that were identified by 2 observers | 59 | 20.2 | 52 | 17.8 |

| No. of β-GAL nuclei that were identified by 3 observers | 69 | 23.6 | 143 | 49.0 |

| Fleiss κ | 0.466 | 0.592 | ||

n, No. of experiments.

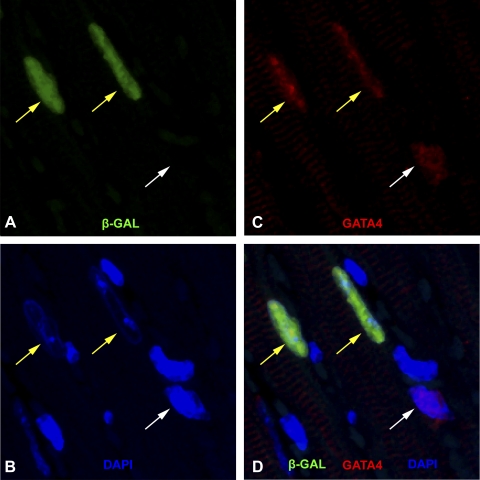

Diagnostic performance of GATA4 immune reactivity.

Although GATA4 signals colocalized with ∼90% of β-GAL nuclei, up to a third of the total GATA4 signals were β-GAL negative. This gives an overall sensitivity of 91.2% [confidence interval (CI): 89.1–94.3%], specificity of 88.7% (CI: 86.9–90.3%), positive predictive power of 72% (CI: 67.7–75.4%), and negative predictive power of 97.3% (CI: 96.2–98.1%). The diagnostic accuracy for myocyte nuclei (89.5%) was comparable to those using WGA.

DISCUSSION

This study highlights the limitations of conventional approaches to identify myocyte nuclei in histologic sections of the heart. In the absence of membrane markers, the identification of myocyte nuclei using confocal microscopy in conjunction with myocyte-restricted structural protein immune cytology can be difficult, and the overall sensitivity of identifying myocyte nuclei with confocal microscopy averaged 43% in our study. The use of membrane markers such as WGA improved the sensitivity of myocyte nucleus identification to an average of 65%. The use of WGA improved specificity from an average value of 89% to 97%. Similar trends were observed for the overall diagnostic accuracy and predictive power calculations. Although the ability to identify myocyte nuclei was relatively consistent between different observers, the fact that any discrepancy was observed indicates at least some degree of subjectivity in the process. Importantly, the degree of interobserver variability was decreased and the overall accuracy was increased with the use of WGA.

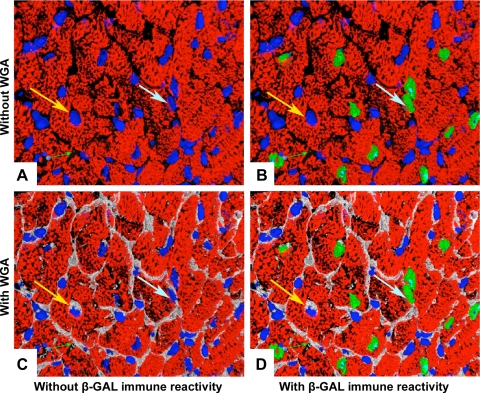

Problems typically encountered in nuclear identification in histologic sections are shown in Fig. 2. In the absence of WGA, the nucleus identified by the yellow arrow appears located centrally within a myocyte cell body and was misidentified by our investigators as being of myocyte origin. Although the use of membrane markers can aid myocyte identification (compare Fig. 2, A and C), it is still far from ideal. For example, the nucleus identified by the light blue arrow in Fig. 2 appeared to lie within the periphery and interstitial space and was misidentified as being of nonmyocyte origin. These examples illustrate the intrinsic difficulty in nuclear identification, despite the use of confocal approaches.

Fig. 2.

Typical problems encountered in nuclear identification. Yellow arrow shows a nonmyocyte nucleus surrounded by the myocyte cytoplasm, which was thought to be of myocyte origin. Light blue arrow points to a misidentified myocyte nucleus that was located in the periphery of a myocyte (see text for detailed explanation of arrows). Pseudocoloring: white = cell membrane delineated by WGA, red = troponin T, blue = DAPI nuclear counterstain, and green = β-GAL myocyte nucleus.

Interestingly, this study also demonstrates that the plane of section can influence the accuracy of myocyte nucleus identification. The sensitivity and specificity were higher in myocytes aligned predominantly in the transverse orientation relative to the X-Y axis, with or without the aid of a membrane marker. Given that, in the transverse orientation, the longest dimension of the myocyte is perpendicular to the plane of section, the probability that a nonmyocyte will overlie a myocyte is reduced. This likely contributes to the higher values for sensitivity and specificity as well as diagnostic accuracy for transverse sections.

Perhaps it is not surprising that the use of confocal microscopy failed to correctly identify all myocyte nuclei when used in conjunction with a cytoplasmic myocyte marker. Although the theoretical lateral and axial resolution of confocal microscopy are in the order of ∼0.2 and 0.5 μm, respectively, a number of factors conspire to reduce resolution in practice (3). These include differences in the refractive index of the embedding medium vs. that of the immersion medium, differences in excitation and emission wavelengths, imaging depth, and cover glass thickness. One can calculate the three-dimensional theoretical point spread function for the imaging conditions utilized, and from that determine the lateral and axial resolution [which is set at the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the point spread function]. For our studies, at an imaging depth of 0 μm, the theoretical lateral and axial resolution were 0.18 and 0.43 μm at an excitation wavelength of 405 nm and 0.28 and 0.51 μm at an excitation wavelength of 633 nm, respectively (see http://www.svi.nl/support/wiki/HuygensCommand_stat). In reality, however, the theoretical and the experimental values for the axial FWHM markedly differ. For example, Fleiss (4) measured an axial FWHM of 0.85 μm using comparable imaging conditions to the present study, a value approximately double the theoretical value. Given the close proximity of nonmyoycte nuclei and myocyte cytoplasm (often <0.5 μm) (13), and given the intrinsic and practical physical limitations of confocal microscopy, errors in myocyte nucleus identification can readily be explained.

The use of nuclear transcriptional factors such as GATA4 and Nkx 2.5 for myocyte identification also has its limitations. From our results, there is a one in three chance a GATA4 signal belongs to a nonmyocyte nucleus in the adult heart (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with previous reports that GATA4 and Nkx 2.5 are not exclusively expressed in myocyte nuclei in the adult heart (5, 10, 16, 17).

Fig. 3.

Relationship between GATA4 and β-GAL immune reactivity. A: nuclei with positive β-GAL immune reactivity (pseudocolored green). B and C: GATA4 positive nuclei (red) and DAPI (blue) nuclei staining, respectively, within the same field. The merged image is represented in D. The yellow arrows point to nuclei that had positive GATA4, and β-GAL immune reactivities. The white arrow points to a GATA4 positive nucleus, which lacked β-GAL signal.

Taken into context of our results, if the chance of misindentifying a myocyte nucleus with current methodologies ranges from 1 in 3 to 1 in 10, then accurate quantification of myocyte nuclear events cannot be obtained, particularly when the events are rare (such as myocyte proliferation). These data support the notion that transgenic lineage reporters are useful for monitoring nuclear events in myocytes, especially in these circumstances. Indeed, previous studies utilized the MHC-nLAC reporter system to monitor myocyte DNA synthesis in uninjured adult hearts (12). These analyses employed a single injection of tritiated thymidine, followed by a 4-h chase period. Hearts were then harvested and sectioned, and the sections were reacted with X-GAL and subjected to autoradiography. Only 0.0005% of the myocytes were observed to be synthesizing DNA (as evidenced by the presence of silver grains over blue nuclei). If one normalizes this value for daily accumulation, and then for annual accumulation, these data would suggest a myocyte turnover rate of roughly 1.1% per year [i.e., 0.0005% × (24 h·day−1·4-h chase period−1) × 365 days/yr].

This result for the mouse myocardium was remarkably similar to data recently obtained by Bergmann and colleagues (2) for the human myocardium. This latter study used cardiac samples from individuals who were born before or after the ban on above-ground nuclear testing and relied on the incorporation of 14C-labeled carbon in the biosphere (and, subsequently, in newly synthesized DNA) to birth date new cells. Cardiac myocyte nuclei were isolated via fluorescence-activated cell sorting using an antibody recognizing a myocyte nuclear-restricted motif. A myocyte turnover rate of 1% per year for individuals at 20 years of age was reported. Finally, it is of interest to consider the source of myocyte renewal. The mouse experiment noted above utilized a 4-h chase after isotope exposure and, as such, only captured DNA synthesis occurring in preexisting myocytes. In contrast, the human experiment relied on the cumulative incorporation of isotope and, as such, would capture preexisting myocytes that were synthesizing DNA as well as cycling stem cells, which subsequently differentiated into myocytes. Potential species differences notwithstanding, the similar annual turnover rates obtained with these two studies suggest that myocyte proliferation, rather than myogenic neodifferentiation, is the major mechanism giving rise to myocyte renewal in the uninjured adult mammalian heart.

In conclusion, our study illustrates the intrinsic limitations encountered when using conventional approaches to identify myocyte nuclei in histologic sections. The sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy achieved with confocal approaches in combination with image segmentation may not be sufficient for correct identification of rare myocyte nuclear events such as proliferation, apoptosis, and trans-differentiation. By accurately determining the predictive values for individual observers (as was done here using the MHC-nLAC model), it should be possible to determine if the nuclear events being studied occur at a sufficiently large frequency such that they can be scored with confidence when using segmentation of confocal images.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Jenny and Richard Edwards for help with histopathology, Nicola Harris for secretarial support, and Bristol Myer Squib for a Cardiovascular Prize Fellowship awarded to L. Shenje.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anversa P, Leri A, Kajstura J. Cardiac regeneration. J Am Coll Cardiol 47: 1769–1776, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabe-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S, Frisen J. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 324: 98–102, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter D. Practical considerations for collecting confocal images. Methods Mol Biol 122: 35–57, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull 76: 378–382, 1971 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glenn DJ, Rahmutula D, Nishimoto M, Liang F, Gardner DG. Atrial natriuretic peptide suppresses endothelin gene expression and proliferation in cardiac fibroblasts through a GATA4-dependent mechanism. Cardiovasc Res 84: 209–217, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha T, Li Y, Hua F, Ma J, Gao X, Kelley J, Zhao A, Haddad GE, Williams DL, William Browder I, Kao RL, Li C. Reduced cardiac hypertrophy in toll-like receptor 4-deficient mice following pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res 68: 224–234, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33: 159–174, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leri A, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells and mechanisms of myocardial regeneration. Physiol Rev 85: 1373–1416, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luna LG. Manual of Histologic Staining Methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Blakiston Division New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molkentin JD. The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem 275: 38949–38952, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubart M, Field LJ. Cardiac regeneration: repopulating the heart. Annu Rev Physiol 68: 29–49, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soonpaa MH, Field LJ. Assessment of cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis in normal and injured adult mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H220–H226, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soonpaa MH, Field LJ. Survey of studies examining mammalian cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis. Circ Res 83: 15–26, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soonpaa MH, Kim KK, Pajak L, Franklin M, Field LJ. Cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and binucleation during murine development. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H2183–H2189, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soonpaa MH, Koh GY, Klug MG, Field LJ. Formation of nascent intercalated disks between grafted fetal cardiomyocytes and host myocardium. Science 264: 98–101, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu SM, Fujiwara Y, Cibulsky SM, Clapham DE, Lien CL, Schultheiss TM, Orkin SH. Developmental origin of a bipotential myocardial and smooth muscle cell precursor in the mammalian heart. Cell 127: 1137–1150, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaglia T, Dedja A, Candiotto C, Cozzi E, Schiaffino S, Ausoni S. Cardiac interstitial cells express GATA4 and control dedifferentiation and cell cycle re-entry of adult cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 653–662, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]