Abstract

The translation initiation region (TIR) of the Escherichia coli rpsA mRNA coding for ribosomal protein S1 is characterized by a remarkable efficiency in driving protein synthesis despite the absence of the canonical Shine–Dalgarno element, and by a strong and specific autogenous repression in the presence of free S1 in trans. The efficient and autoregulated E.coli rpsA TIR comprises not less than 90 nt upstream of the translation start and can be unambiguously folded into three irregular hairpins (HI, HII and HIII) separated by A/U-rich single-stranded regions (ss1 and ss2). Phylogenetic comparison revealed that this specific fold is highly conserved in the γ-subdivision of proteobacteria (but not in other subdivisions), except for the Pseudomonas group. To test phylogenetic predictions experimentally, we have generated rpsA′–′lacZ translational fusions by inserting the rpsA TIRs from various γ-proteobacteria in-frame with the E.coli chromosomal lacZ gene. Measurements of their translation efficiency and negative regulation by excess protein S1 in trans have shown that only those rpsA TIRs which share the structural features with that of E.coli can govern efficient and regulated translation. We conclude that the E.coli-like mechanism for controlling the efficiency of protein S1 synthesis evolved after divergence of Pseudomona

INTRODUCTION

The importance of knowing about microbial evolution started to be appreciated by the early 1980s when rRNA-based phylogeny of prokaryotes began to emerge (1). Phylogenetic analysis appeared to be a powerful method to prove the reliability of RNA secondary structures predicted by computer modeling or by in vitro enzymatic/chemical probing. Phylogenetic comparison of stable cellular RNAs (tRNAs, rRNAs, RNase P RNA and tmRNA) shows that conservation of their secondary/tertiary structures is essential for their functions. Much fewer data have been accumulated on the phylogeny of the mRNA regulatory regions.

Several available examples demonstrate that in eubacteria, conservation of the regulatory secondary structure elements of mRNA can either embrace very distant species or be specific only for a certain bacterial subgroup. Thus, long untranslated leaders of mRNAs of thiamine biosynthetic genes contain the so-called thi box, a regulatory element that exerts its function by forming specific secondary structure (2). Expression of the thi box mRNAs is negatively regulated by thiamine derivatives which directly modulate the formation of the structure inhibitory for ribosome recruitment, without the need for auxiliary proteins (3). The thi box element appeared to be highly conserved in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as in archaea [Miranda-Rios et al. (2) and references therein]. Mechanisms analogous to the thiamine-sensing system were also proposed to function with coenzyme B12 and with other potential riboswitch effectors such as flavin mononucleotide (4). These metabolites are believed to be molecular fossils of an ancient ‘RNA world’ when they served as specific RNA modulators before the advent of regulatory proteins.

More often, mRNA structures involved in translational control are far less conserved, being specific only for a certain bacterial branch. This indicates that they had appeared during a relatively recent period of bacterial evolution. Thus, translational control mediated by the rpoH mRNA secondary structure (5) has been found to be a conserved mechanism for the heat shock induction of σ32 (RpoH) synthesis in γ-proteobacteria, whereas in the α-subdivision, the heat shock regulation of RpoH occurs primarily at the level of transcription (6,7). Another example is the control of the endoribonuclease RNase E which negatively regulates its own synthesis by degrading rne mRNA with a higher rate than other cellular messages (8). The long highly structured 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of the rne mRNA contains two secondary structure elements necessary for preferential degradation by RNase E. Despite extensive sequence divergence, the secondary structure of the rne leader was found to be highly conserved among diverse members within the γ-subdivision of proteobacteria, suggesting that this group evolved common mechanisms to control RNase E (9). Similar observations were reported for the regulatory region of the S10 operon which is negatively controlled by ribosomal protein L4 at both the transcriptional and translational level (10). Conservation of the secondary structure of the 5′-UTR necessary for the L4-mediated regulatory mechanisms was shown for different families within γ-proteobacteria, with only one exception: the S10 leader of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cannot be folded in the same manner and, consistently, is not subjected to regulation by L4 in Escherichia coli (10).

It has recently been suggested that translational control of protein S1 synthesis, another essential regulatory circuit in Gram-negative bacteria, exhibits the same tendency (11). In E.coli, the unique secondary/tertiary structure of the rpsA translation initiation region (TIR) ensures highly efficient translation despite the absence of a canonical Shine–Dalgarno (SD) element upstream of the initiation codon. The E.coli-like fold of the rpsA TIR as well as the absence of a conventional SD sequence appeared to be highly conserved in γ-proteobacteria, again except for Pseudomonas species (11). Here, we have experimentally tested the rpsA TIRs from several representatives of this bacterial phylum (Salmonella typhimurium, Yersenia pestis, Haemophilus influenzae, Buchnera aphidicola, Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) for their ability to drive efficient and regulated protein synthesis in E.coli. Pseudomonas rpsA regulatory regions folding into a completely different structure appeared to be the least efficient, despite the presence of conventional SD elements. The results emphasize the crucial role of the rpsA TIR fold in translational control of protein S1 synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial species, plasmids and abbreviations

Genome DNA from the following bacteria were used as sources of the rpsA regulatory regions: E.coli K12 (Eco), Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium LT2 (Sty), Y.pestis (Yp), H.influenzae (Hin), B.aphidicola (Baph), P.aeruginosa PAO1 (Paer) and P.putida (Pput). The S.typhimurium LT2 and H.influenzae (clinical isolate) were provided by the Department of Microbiology of Sechenov Moscow Medical Academy, P.putida and P.aeruginosa were from the Institute of Molecular Genetics RAS. Yersenia pestis DNA was provided by O. Podladchikova (Research Institute for Plague Control, Rostov-on-Don, Russia). Plasmid pBS2S1-21 (12) bearing the genes aspS-trxB-serS-serC-aroA-rpsA-himD-tpiA from B.aphidicola (Baph), the endosymbiont of Schizaphis graminum (Sg), was a gift of P. Baumann (Microbiology Section, University of California, Davis, CA). The plasmid pEMBLΔ46 (13) served for cloning the rpsA TIRs from the above bacteria in-frame with the lacZ sequence and transporting the rpsA′–′lacZ fusions onto the chromosome of E.coli [ENSO strain; former name HfrG6Δ12; see Dreyfus (13)]. The plasmid pSP261 (here designated as pS1) is a derivative of pACYC184 (pCtr) bearing the Eco_rpsA gene under its own promoter system (14).

Construction of the chromosomal rpsA′–′lacZ fusions

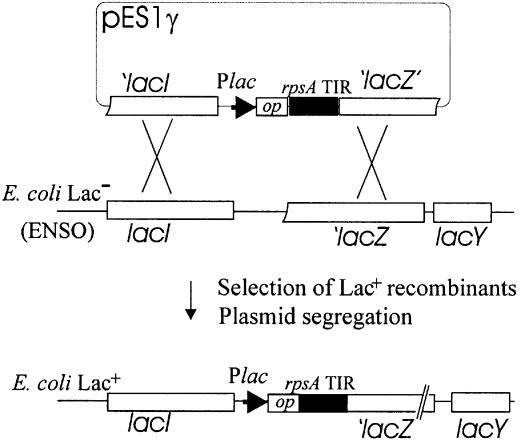

DNA fragments corresponding to the rpsA TIRs from various bacterial species were amplified from genome DNA templates using primers designed according to available genome sequences. BamHI and HindIII site sequences were included in the forward and reverse primers, respectively, to facilitate the in-phase cloning of the amplified fragments in front of the lacZ coding sequence of pEMBLΔ46 devoid of the genuine lacZ ribosome-binding site (13). The resulting plasmids pES1γ (pES1Sty, pES1Hin, pES1Yp, pES1Baph, pES1Paer, pES1Pput) bearing translational rpsA′–′lacZ fusions were selected by α-complementation, verified by sequencing and used to transform ENSO [Lac– derivative of HfrG6 devoid of the lac promoter-lacZ RBS region; see Dreyfus (13)]. The rpsA′–′lacZ fusions were then transferred onto the chromosome of ENSO by homologous recombination, selecting for a Lac+ phenotype (Fig. 1). The ssyF29 mutation (15) and its neighbor Tn10 (16) were P1 transduced into each strain to obtain two types of otherwise isogenic Tetr transductants (rpsA+ and rpsA::IS10). The transductants were then transformed with S1-expressing plasmid (pS1) or with a parent vector (pCtr) to monitor autogenous control essentially as described (16).

Figure 1.

Construction of E.coli strains in which the rpsA TIRs from various γ-proteobacteria govern translation of the chromosomal lacZ gene. The PCR fragments carrying the rpsA regulatory regions have been first cloned in-phase with the α-peptide gene (‘lacZ’) of pEMBLΔ46, generating pES1γ (pES1Sty, pES1Yp, pES1Baph, etc.), and then transferred onto the chromosome of the Lac– E.coli strain (ENSO) by homologous recombination between lac sequences present on both the plasmid and chromosome. ENSO carries a deletion encompassing the lac promoter/operator region and ribosome-binding site of the lacZ gene. Plac and op are the promoter and operator of the lac operon.

Growth of cells and β-galactosidase assays

Cell growth and β-galactosidase assays were performed as described previously (16) with minor modifications. Cells were harvested in the mid-log phase (A600 ∼0.4–0.5) after at least four generations of balanced growth in LB medium (5 ml) supplemented with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 0.2 mM) and chloramphenicol (34 µg/ml). Cell pellets obtained by low speed centrifugation at 4°C (from 3–4 ml culture) were resuspended in chilled phosphate-buffered saline buffer (200 µl) containing lysozyme (200 µg/ml) and then subjected to a repeated thawing–freezing procedure. All β-galactosidase activities measured in clarified cell lysates according to Miller (17) are expressed in nmol of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) hydrolyzed/min/mg of total soluble cell proteins.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the Buph- and Hin-rpsA regulatory regions

To restore the E.coli-like SD sequence in the Buph_rpsA TIR which lost the SD remnant (GAAUBaph→GAAGEco), two PCR fragments were obtained on pES1Baph with two pairs of primers: UPlac–cSDbaph and SDbaph–DSlac (Table 1). The PCR products were mixed and amplified in the presence of UPlac and DSlac. The resulting fragment was treated with BamHI and HindIII and cloned in pEMBLΔ46 to create pES1BaphSD.

Table 1. Primers used for site-directed mutagenesis of the Baph_ and Hin_rpsA TIRs.

| Name | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| SDbaph | GAAGATTATTAATATGAATGAATCTTTTGCa |

| cSDbaph | GCAAAAGATTCATTCATATTAATAATCTTCa |

| Eco-ss1-HinII | TATGTTAAACAACCCCGCATTTTATGGb |

| cEco-ss1-HinI | GTTTAACATAAGGATAAATGCTTATTC c |

| cHinII-ss1-HinI | GCGGGGTTGTTTAACATAAGG d |

| DSlac | GGCGATTAAGTTGGGTAACGCCAGGGe |

| UPlac | GTTAGCTCACTCATTAGGCACCCCf |

aAn initiator codon of the Baph_rpsA TIR is in bold; the base mutated is underlined.

bThe Eco-ss1 region (bold italic) is followed by the Hin sequence covering the left part of the central hairpin II.

cThe primer is complementary to the Eco-ss1 (bold italic) and the right part of the Hin hairpin I including the apical loop.

dThe primer is complementary to the left part of the Hin hairpin II, Eco-ss1 (in bold italic) and the right part of the Hin hairpin I.

eThe primer is complementary to the region (+57 to +82) of the genuine lacZ mRNA (+1 is A of the lacZ AUG start codon).

cThe primer covers the positions from –64 to –41 with respect to the transcription start point of the lac-operon.

To restore the E.coli-like design of the Hin_rpsA TIR, the Eco-ss1 was inserted in front of hairpin II (HII) and behind HI of H.influenzae by PCR on pES1Hin with primers Eco-ss1-HinII and DSlac, and with cEco-ss1-HinI and UPlac (Table 1). To provide a good overlap of PCR fragments, the latter product was extended by PCR with primers UPlac and cHinII-ss1-HinI. Finally, the products were mixed and amplified in the presence of UPlac and DSlac. After treatment with BamHI and HindIII, the resulting fragment was cloned in pEMBLΔ46 to give pES1Hin+Ecoss1. New constructs were checked by sequencing. Corresponding ENSO derivatives were generated by homologous recombination.

Phylogenetic analysis of secondary structures

The search for the rpsA TIRs within accessible microbial genomes (finished and unfinished at NCBI BLAST server http://www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov./blast) was described previously (11). RNA folding was performed using the Eco_rpsA TIR structure as a model (11). The rpsA regulatory regions of P.aeruginosa (DDB/EMBL/GenBank AE004740) and P.putida (AE016780) were folded with the use of the mfold program (http://bioinfo.math.rpi.edu/~mfold).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of the rpsA–lacZ fusions bearing rpsA TIRs from various bacterial species

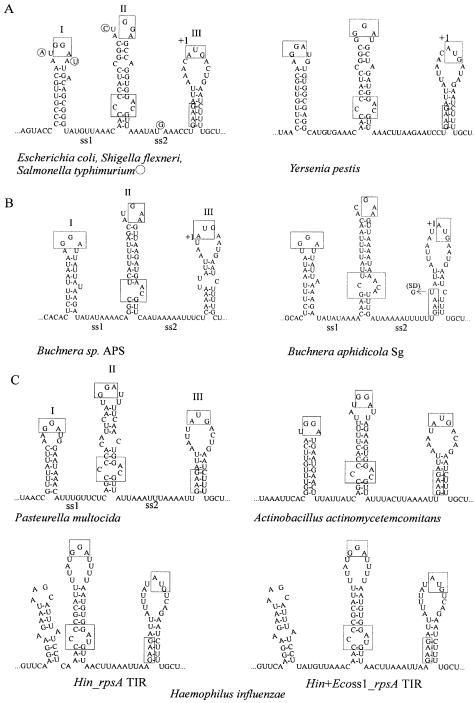

Recently, we have noticed that despite the absence of sequence conservation, the majority of available rpsA leaders from the γ-subdivision of purple bacteria, except for the Pseudomonas species, can be folded into a particular secondary structure specific for the E.coli rpsA 5′-UTR (11). This fold comprises three hairpins (HI, HII and HIII) separated by A/U-rich single-stranded regions ss1 and ss2 (Fig. 2). Phylogenetic comparison revealed that rpsA TIRs of related γ-bacteria share such remarkable features as the absence of a canonical SD sequence, the presence of conserved GGA sequences in apical loops of two stable hairpins HI and HII (GAA in a loop II in Buchnera species), an internal loop at the bottom of HII and, finally, a well conserved weak initiator HIII with an initiator codon on its top and a degenerate SD sequence in a stem. As was shown for the Eco_rpsA TIR, this specific fold and conserved features are responsible for both the high translation efficiency and strong autogenous control, implying that the rpsA TIR works like eukaryotic IRES elements by forming a spatially optimized ribosome-binding structure (11). In the present work, we tested the rpsA TIRs from a representative series of γ-proteobacteria, i.e. S.typhimurium LT2 (Sty), Y.pestis (Yp), H.influenzae (Hin), B.aphidicola (Baph), P.aeruginosa (Paer) and P.putida (Pput), for their capability to drive protein synthesis in E.coli. To compare the rpsA TIR efficiencies quantitatively, we measured the β-galactosidase yield from single-copy translational fusions of the rpsA regulatory regions with the chromosomal lacZ gene (Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

The rpsA TIRs of γ-proteobacteria (A–C) possessing the E.coli-like fold. Conserved sequence/structure elements are boxed. (A) Enterobacteria. The bases in the Sty_rpsA TIR differing from E.coli are circled. (B) Buchnera species, endosymbionts of Acyrthosiphon pisum (APS) and Schizaphis graminum (Sg). (C) Pasteurellaceae species with known rpsA sequences. Beside the wild-type Hin_rpsA TIR structure, a mutant variant with the Eco-ss1 inserted in between the hairpins I and II (Hin+Ecoss1_rpsA TIR) is shown.

To construct rpsA′–′lacZ fusions, DNA fragments coding for the rpsA TIR from different bacterial species were generated by PCR, cloned in pEMBLΔ46 in-frame with lacZ and transferred onto the E.coli chromosome by homologous recombination. The length of the inserted fragments roughly corresponded to that of the Eco_rpsA TIR, with the 5′-UTR necessary and sufficient to provide both a high translation level and autogenous control (11,16). Accordingly, all the DNA fragments comprised ∼95 nt upstream of the initiator codon and the first 18–20 codons of the rpsA gene. To monitor the negative control by S1 of E.coli (Eco-S1), we used two in vivo tests: evaluation of the β-galactosidase yield in the presence of an S1-expressing plasmid (pS1) in wild-type cells (rpsA+), and evaluation of the β-galactosidase activity in the rpsA mutant defective in autogenous control [ssyF29 bearing the rpsA::IS10 allele; see Boni et al. (16)]. In the latter case, the Eco_rpsA–lacZ fusion was shown to exhibit an ∼3-fold increase in activity (relative to that in the rpsA+ cells) due to the de-repression of the rpsA TIR in the mutant (16). This de-repression was attributed to a reduced ability of the C-truncated S1 to form a tight repressor complex and/or to the slow rate of S1 accumulation in a cell caused by destabilization of the rpsA mRNA by the IS10 insertion in the 3′ part of the rpsA gene (16).

Functional activities in E.coli of the rpsA TIRs possessing the E.coli-like fold

Folding of the rpsA TIRs from enterobacteria, including the Buchnera genus, and from Pasteurellaceae shows a close resemblance to Eco_rpsA TIR (Fig. 2). The β-galactosidase assays have revealed that this fold provides high translation efficiency but not necessarily strong S1-mediated control (Table 2).

Table 2. Activities of the rpsA TIRs from γ-proteobacteria in E.coli and their regulation by E.coli S1.

| β-Galactosidase activitya | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin of the rpsA TIR | rpsA+/pCtrb | rpsA+/pS1b | ssyF29/pCtrb | ssyF29/pS1b |

| E.coli | 19 000 ± 1500 | 800 ± 150 | 58 000 ± 3000 | 1100 ± 250 |

| S.typhimurium | 15 500 ± 1500 | 550 ± 150 | 52 500 ± 1100 | 650 ± 100 |

| Y.pestis | 6200 ± 1600 | 650 ± 150 | 12 600 ± 1800 | 700 ± 200 |

| B.aphidicola Sg | 2300 ± 550 | 1800 ± 350 | 2600 ± 400 | 1550 ± 300 |

| BaphSD_rpsA TIRc | 6300 ± 750 | 2500 ± 300 | ND | ND |

| H.influenzae | 37 500 ± 6400 | 26 000 ± 2800 | 52 300 ± 5500 | 30 600 ± 4200 |

| Hin+Ecoss1_rpsA TIRd | 22 600 ± 3500 | 14 500 ± 2500 | 32 500 ± 4000 | 17 200 ± 3500 |

| P.putida | 960 ± 100 | 600 ± 150 | 1100 ± 230 | 350 ± 50 |

| P.aeruginosa | 900 ± 100 | 450 ± 150 | 1050 ± 200 | 570 ± 150 |

aThe β-galactosidase level in strains bearing the rpsA′–′lacZ translational fusions is expressed in nmol of ONPG hydrolyzed/min/mg of total soluble protein. Average of three or more independent assays.

bEscherichia coli cells bearing the wild-type (rpsA+) or ssyF29 (rpsA::IS10) alleles and an empty vector pACYC184 (pCtr) or its S1-expressing derivative (pS1).

cA mutant variant of the Baph_rpsA TIR with the E.coli-like SD sequence.

dA mutant variant of the Hin_rpsA TIR with the E.coli ss1 region inserted between hairpins I and II (see Fig. 2).

As expected, the members of the Enterobacteriaceae follow the E.coli-like mechanism to control S1 synthesis. This family includes the closest relatives of E.coli (18–22), and primary structures of ribosomal components of enterics are well conserved. In particular, protein S1 of S.typhimurium as well as S1 of other serovars of S.enterica (typhi and paratyphi A) has 99% identity with Eco-S1, and S1 of the more distant Y.pestis has 95% identity (data obtained by using the NCBI BLAST server). Although intercistronic regions are usually much less conserved than coding sequences, the rpsA 5′-UTR of Shigella flexneri has 100% identity with E.coli (22) and that of S.enterica serovars differs from the Eco_rpsA TIR only at four positions (Fig. 2A). Much more divergent is the Yp_rpsA TIR, especially HI, but, remarkably, the stability of its structure is almost the same as that of E.coli or Salmonella. Consistent with the high sequence homology, the Sty_rpsA TIR shows about the same activity as the Eco_rpsA TIR in driving translation, and is strongly repressed by Eco-S1 in trans, indicating that small differences in primary structure between the Sty_ and Eco_rpsA TIRs are not essential for regulation. The Yp_rpsA TIR drives less efficient but still regulated synthesis in E.coli, although the repression level is lower than for Eco_rpsA TIR, presumably owing to extensive sequence divergence (Table 2).

The Buchnera genus of Enterobacteriaceae includes non-culturable prokaryotic endosymbionts found within specialized cells in aphids (23–26). The endosymbiosis was established at least 150 million years ago, and the closest free-living relatives of B.aphidicola are enterobacteria (24). Despite the great reduction of the genome size due to the massive loss of genes and regulatory signals in the lineage leading to Buchnera, this genus not only retained the rpsA gene encoding S1 highly homologous to Eco/Sty S1 [75% identity, see Clark et al. (26)] but also preserved the design of the rpsA regulatory region (Fig. 2B). Since Buchnera lost most SD signals (24), the conservation of the functional rpsA gene is fully consistent with the known fact that Gram-negative bacteria can correctly recognize and translate mRNAs lacking an SD in their 5′-UTR exclusively due to the presence of S1 (27–29).

The stability of the overall rpsA TIR structure is much lower in Buchnera than in enterics because of the AU-richness that reflects genome-wide base compositional bias favoring A and T (24). Other features differing from the Eco_rpsA TIR are the complete absence of the SD remnant, the loss of one G in the highly conserved GGA sequence in the apical loop II, and the different configuration of an internal loop and a bottom helix in the HII (Fig. 2B). This significant divergence affects functioning of the Baph_rpsA TIR in E.coli: it is less efficient than rpsA TIRs of enterics and its activity cannot be regulated by Eco-S1 (Table 2). Nevertheless, the translation level is higher than in the case of Pseudomonas rpsA TIRs, although they comprise conventional SD motifs: AGGU (P.aeruginosa) and AGGA (P.putida). We conclude that the efficiency of the Baph_rpsA TIR is determined mainly by the TIR fold.

To find out how the absence of the SD remnant affects an activity of Baph_rpsA TIR in E.coli, we restored the E.coli-like SD sequence (GAAU→GAAG) by site-directed mutagenesis. This led to an ∼2.5-fold increase in activity and slightly restored the negative control by Eco-S1 in trans (Table 2). On the one hand, this may indicate that even such an imperfect SD sequence is able to fulfil the SD function in the context of the rpsA TIR fold, namely to provide more rapid positioning of the start codon in the ribosomal P-site. On the other hand, we cannot exclude that increases in activity may result from restoring the E.coli-like stem of HIII, and hence the overall TIR configuration, rather than the SD as such. Indeed, the Eco_rpsA TIR SD mutant (GAAG→GAAC) lost only 25% of its activity when the stem–loop structure III was not destroyed (11). We suppose that the loss of the SD remnant in Baph_rpsA TIR as well as in other Buchnera genes most probably resulted from the endosymbiotic lifestyle. Slow growth rate due to the low efficiency of translation signals may help in adapting bacterial reproduction to the needs of the host.

The H.influenzae rpsA TIR represents one more example of impaired regulation by S1 in trans (Table 2). According to the evolutionary relationships established in the 16S rRNA tree (30–33), Pasteurellaceae are closely related to the enterobacterial cluster. The comparison of the rpsA TIR folds of three species from this family (Fig. 2C) shows high conservation of the main features, except for H.influenzae. The Hin_rpsA TIR is unique in that it lacks the HI and ss1 region. In place of E.coli-like HI, the Hin_rpsA TIR contains a smaller but rather stable hairpin bearing the stop codon of the preceding cmk gene in its apical loop. In all other cases, this stop codon is located several nucleotides upstream of the 5′ edge of HI. This makes the Hin_rpsA TIR especially interesting as a naturally truncated variant of the rpsA regulatory region. We included the hairpin with the cmk terminator codon in the Hin_ rpsA′–′lacZ fusion assuming that it may serve for stabilization of the overall TIR structure. Strikingly, this construct directed very efficient (>1.5-fold more efficient than the Eco_rpsA TIR) but faintly regulated β-galactosidase synthesis (Table 2). It suggests that HI and ss1 are dispensable for efficient ribosome recruitment but not for repressor complex formation. More precisely, taking into account the data for the Baph_rpsA TIR (see above), it means that HI and ss1 are necessary but not sufficient for negative regulation by Eco-S1 in trans.

The high translation efficiency of Hin_rpsA TIR together with its inability to serve as a target for negative control by S1 indicates that both features can be separated. By its high activity and the absence of S1-mediated repression, the Hin_rpsA TIR is reminiscent of the Eco_rpsA TIR mutants where the strengthening of the bottom helix of HII led to a substantial increase in the TIR activity and to a loss of autocontrol (11), but the Hin_rpsA TIR achieved the same effect by other means. It is likely that the small hairpin immediately 5′ to the Hin HII increases the stability of the HII and serves to maintain a TIR conformation optimal for efficient ribosome recruitment.

In an attempt to restore S1-mediated control, we separated the first two hairpins by the ss1 region of the Eco_rpsA TIR (Fig. 2C). Although the new configuration is closer to that of E.coli, it is not noticeably regulated by S1 either. Moreover, it is less efficient than the wild-type Hin_rpsA TIR (Table 2). Thus, mechanistic reconstitution of a secondary structure resemblance is not sufficient for restoring the S1-mediated regulation, indicating that the latter is most probably provided by tertiary structure elements.

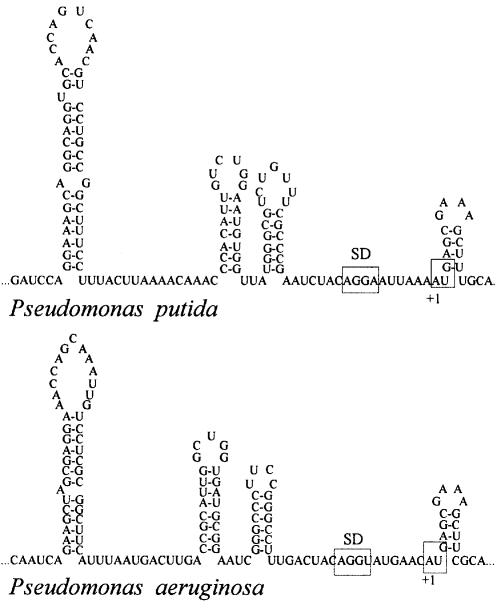

The rpsA TIRs of γ-proteobacteria with the fold differing from that of E.coli

There are at least two families in γ-proteobacteria where the rpsA TIR did not adopt the E.coli-like fold, i.e. Pseudomonadaceae (34) and Xanthomonadaceae. The translation apparatus of Pseudomonas still remains far less studied than that of E.coli, but several observations point to the existence of essential differences. First, an rRNA operon from P.aeruginosa failed to replace the E.coli rrn operon in a specialized strain with all seven rRNA operons deleted, whereas rRNA operons from enterobacteria S.typhimurium and Proteus vulgaris were functional in this system (35). Secondly, the leader of the P.aeruginosa S10 (rpsJ) operon folds into a structure entirely different from that of E.coli and, consequently, it does not serve as a target for the L4-mediated autogenous control in E.coli (10). Similarly, the rpsA leaders of P.putida and P.aeruginosa have not adopted the E.coli-like fold. Yet, they are also highly structured, and their folding patterns clearly resemble each other (Fig. 3). In addition, unlike all other available rpsA leaders from γ-proteobacteria, they bear conventional SD sequences: AGGA (Pput) and AGGU (Paer) embedded in single-stranded regions. Despite this fact, both Paer_ and Pput_rpsA TIRs appeared to be the least active in E.coli (20 times less efficient than Eco_rpsA TIR, Table 2). As ribosomal protein synthesis should be kept at a high and regulated level, it is logical to suppose that the secondary/tertiary structure of the Paer_ and Put_rpsA TIRs is well adjusted to provide sufficient S1 for the Pseudomonas translational machinery, but this fold is not efficiently recognized by ribosomes from distant E.coli. All these data suggest that divergence of Pseudomonadaceae from other families of γ-proteobacteria preceded the co-evolution of translational machinery and fine mechanisms controlling ribosome biogenesis. Recent sequencing data show that at least one more family from γ-proteobacteria does not follow the E.coli-like mode to control S1 synthesis: the species from Xantomonadaceae (DDB/EMBL/GenBank AE012326, AE012558, AE011867) contain rpsA leaders highly enriched with G residues and adopted the structure differing from that of E.coli.

Figure 3.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and P.putida rpsA TIRs form very similar structures which are completely different from the E.coli-like rpsA TIR fold. The SD elements and initiator codons are boxed.

Concluding remarks

The data obtained here clearly show that the regulatory region of the rpsA mRNA in γ-proteobacteria works mainly due to its specific secondary/tertiary structure being well adjusted to the translational machinery of this bacterial phylum. The rpsA TIRs from enterobacteria and H.influenzae are recognized by E.coli ribosomes as efficient translation initiation signals despite the significant sequence divergence from the Eco_rpsA TIR. Moreover, even the rpsA TIR of B.aphidicola, the weakest among rpsA TIRs possessing the E.coli-like fold and completely lacking the SD remnant, works in E.coli with an efficiency exceeding that of many TIRs bearing the conventional SD domain [e.g. Eco_thrA TIR, see Boni et al. (16); or Pput/Paer_rpsA TIRs, this study]. Although all tested rpsA TIRs, except for Pseudomonas species, drive efficient protein synthesis in E.coli, only those of enterobacteria, i.e. of the closest relatives of E.coli, are subjected to negative regulation by Eco-S1 in trans. Buchnera aphidicola and H.influenzae rpsA TIRs are not involved in a regulatory circuit, indicating that free Eco-S1 does not form a tight complex with these exogenic TIRs in the presence of its cognate TIR in a cell. At present, it is not clear whether these organisms somehow regulate the S1 production, or whether they do not control S1 synthesis at all because during adaptation to the parasitic lifestyle, they modified their metabolism in such a way that they do not require the S1 feedback regulation. We believe that thorough phylogenetic studies of regulatory mRNA secondary structures based on the progress in microbial genome sequencing will be able to provide valuable information on the molecular history of the mechanisms controlling gene expression in bacteria at the post-transcriptional level.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Marc Dreyfus for ENSO and pEMBLΔ46, Olga Podladchikova for Y.pestis DNA, Paul Baumann for the plasmid pBS2S1-21 bearing the rpsA gene of B.aphidicola, Nadezda Skaptzova for oligonucleotide synthesis, and the Department of Microbiology of Sechenov Moscow Medical Academy for H.influenzae and S.typhimurium LT2. We are grateful to Marc Dreyfus for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable comments. This work was supported by the RFBR grants 00-04-48115 and 03-04-49131 to I.V.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fox G.E., Stackebrandt,E., Hespell,R.B., Gibson,J., Maniloff,J., Dyer,T.A., Wolfe,R.S., Balsh,W.E., Tanner,R., Magrum,L. et al. (1980) The phylogeny of prokaryotes. Science, 209, 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miranda-Rios J., Navarro,M. and Soberon,M. (2001) A conserved RNA structure (thi box) is involved in regulation of thiamine biosynthetic gene expression in bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 9736–9741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkler W., Nahvi,A. and Breaker,R.R. (2002) Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nature, 419, 952–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nahvi A., Sudarsan,N., Ebert,M.S., Zou,X., Brown,K.L. and Breaker,R.R. (2002) Genetic control by a metabolite binding mRNA. Chem. Biol., 9, 1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morita M.T., Tanaka,Y., Kodama,T.S., Kyogoku,Y., Yanagi,H. and Yura,T. (1999) Translational induction of heat shock transcription factor σ32: evidence for a built-in RNA thermosensor. Genes Dev., 13, 655–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakahigashi K., Yanagi,H. and Yura,T. (1995) Isolation and sequence analysis of rpoH genes encoding sigma 32 homologs from Gram-negative bacteria: conserved mRNA and protein segments for heat shock regulation. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 4383–4390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakahigashi K., Yanagi,H. and Yura,T. (1998) Regulatory conservation and divergence of σ32 homologs from Gram-negative bacteria: Serratia marcescens, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol., 180, 2402–2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain C. and Belasco,J.G. (1995) RNase E autoregulates its synthesis by controlling the degradation rate of its own mRNA in Escherichia coli: unusual sensitivity of the rne transcript to RNase E activity. Genes Dev., 9, 84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diwa A., Bricker,A.L., Jain,C. and Belasco,J.G. (2000) An evolutionary conserved RNA stem–loop functions as a sensor that detects feedback regulation of RNase E gene expression. Genes Dev., 14, 1249–1260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen T., Shen,P., Samsel,L., Liu,R., Lindahl,L. and. Zengel,J.M. (1999) Phylogenetic analysis of L4-mediated autogenous control of the S10 ribosomal protein operon. J. Bacteriol., 181, 6124–6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boni I.V., Artamonova,V.S., Tzareva,N.V. and Dreyfus,M. (2001) Non-canonical mechanism for translational control in bacteria: synthesis of ribosomal protein S1. EMBO J., 20, 4222–4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thao M.L. and Baumann,P. (1997) Nucleotide sequence of a DNA fragment from Buchnera aphidicola (aphid endosymbiont) containing the genes aspS-trxB-serS-serC-aroA-rpsA-himD-tpiA. Curr. Microbiol., 35, 68–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreyfus M. (1988) What constitutes the signal for the initiation of protein synthesis on Escherichia coli mRNAs? J. Mol. Biol., 204, 79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen S., Skouv,J., Kajitani,M. and Ishihama,A. (1984) Transcriptional organization of the rpsA operon of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet., 196, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiba K., Ito,K. and Yura,T. (1986) Suppressors of the secY24 mutation: identification and characterization of additional ssy genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 166, 849–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boni I.V., Artamonova,V.S. and Dreyfus,M. (2000) The last RNA-binding repeat of the Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S1 is specifically involved in autogenous control. J. Bacteriol., 182, 5872–5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J.H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blattner F.R., Plunkett,C.A., Bloch,C.A., Perna,N.T., Burland,V., Riley,M., Collado-Vides,J., Glasner,J.D., Rode,C.K., Mayhew,G.F. et al. (1997) The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science, 277, 1453–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCleland M., Sanderson,K.E., Spieth,J., Clifton,S.W., Latreille.P., Courtney,L., Prowollik,S., Ali,J., Dante,M., Du,F. et al. (2001) Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature, 413, 852–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkhill J., Wren,B.W., Thomson,N.R., Titball,R.W., Holden,M.T.G., Prentice,M.B., Sebaihia,M., James,K.D., Churcher,C., Mungall,K.L. et al. (2001) Genome sequence of Yersenia pestis, the causative agent of plague. Nature, 413, 523–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCleland M., Florea,L., Sanderson,K., Clifton,S.W., Parkhill,J., Churcher,C., Dugan,G., Wilson,R.K. and Miller,W. (2000) Comparison of the Escherichia coli K-12 genome with sampled genomes of a Klebsiella pneumoniae and three Salmonella enterica serovars, Typhimurium, Typhi and Paratyphi. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 4974–4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wej J., Goldberg,M.B., Burland,V., Venkatesan,M.M., Deng,W., Fournier,G., Mayhew,G.F., Plunkett,G. III, Rose,D.J., Darling,A. et al. (2003) Complete genome sequence and comparative genomics of Shigella flexneri serotype 2a strain 2457T. Infect. Immun., 71, 2775–2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baumann P., Baumann,L., Lai,C.Y., Rouhbakhsh,D., Moran,N.A. and Clark,M.A. (1995) Genetics, physiology, and evolutionary relationships of the genus Buchnera: intracellular symbionts of aphids. Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 49, 55–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moran N.A. and Mira,A. (2001) The process of genome shrinkage in the obligate symbiont Buchnera aphidicola. Genome Biol., 2, 54.1–54.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shigenobu S., Watanabe,H., Hattori,M., Sakaki,Y. and Ishikawa,H. (2000) Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature, 407, 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark M.A., Baumann,L., Baumann,P. and Rouhbakhsh,D. (1996) Ribosomal protein S1 (RpsA) of Buchnera aphidicola, the endosymbiont of aphids: characterization of the gene and detection of the product. Curr. Microbiol., 32, 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts M.W. and Rabinowitz,J.C. (1989) The effect of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S1 on translation specificity of bacterial ribosomes. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 2228–2235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farwell M.A., Roberts,M.W. and Rabinowitz,J.C. (1992) The effect of ribosomal protein S1 from Escherichia coli and Micrococcus luteus on protein synthesis in vitro by E.coli and Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol., 6, 3375–3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzareva N.V., Makhno,V.I. and Boni,I.V. (1994) Ribosome–messenger recognition in the absence of Shine–Dalgarno interactions. FEBS Lett., 337, 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsen G.J., Woese,C.R. and Overbeek,R. (1994) The wind of evolutionary change: breathing new life into microbiology. J. Bacteriol., 176, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeRosa R. and Labedan,B. (1998) The evolutionary relationships between the two bacteria Escherichia coli and Haemophilus influenzae and their putative last common ancestor. Mol. Biol. Evol., 15, 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tatusov R.L., Mushegian,A.R., Bork,P., Brown,N.P., Hayes,W.S., Borodovsky,M., Rudd,K.E. and Koonin,E.V. (1996) Metabolism and evolution of Haemophilus influenzae deduced from a whole-genome comparison with Escherichia coli. Curr. Biol., 6, 279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleishmann R.D., Adams,M.D., White,O., Clayton,R.A., Kirkness,E.F., Kerlavage,A.R., Bult,C.J., Tomb,J.F., Dougherty,B.A., Merrick,J.M. et al. (1995) Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science, 269, 496–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stover C.K., Pham,X.Q., Erwin,A.L., Mizoguchi,S.D., Warrener,P., Hickey,M.J., Brinkman,F.S.L., Hufnagle,W.O., Kowalik,D.J., Lagrou,M. et al. (2000) Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature, 406, 959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asai T., Zaporojets,D., Squires,C. and Squires,C.L. (1999) An Escherichia coli strain with all chromosomal rRNA operons inactivated: complete exchange of rRNA genes between bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 1971–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]