Abstract

The role of the posterior parietal cortex in working memory (WM) is poorly understood. We previously found that patients with parietal lobe damage exhibited a selective WM impairment on recognition but not recall tasks. We hypothesized that this dissociation reflected strategic differences in the utilization of attention. One concern was that these findings, and our subsequent interpretation, would not generalize to normal populations because of the patients older age, progressive disease processes, and/or possible brain reorganization following injury. To test whether our findings extended to a normal population we applied transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) to right inferior parietal cortex. tDCS is a technique by which low electric current applied to the scalp modulates the resting potentials of underlying neural populations and can be used to test structure-function relationships. Eleven normal young adults received cathodal, anodal, or sham stimulation over right inferior posterior parietal cortex and then performed separate blocks of an object WM task probed by recall or recognition. The results showed that cathodal stimulation selectively impaired WM on recognition trials. These data replicate and extend our previous findings of preserved WM recall and impaired WM recognition in patients with parietal lobe lesions.

Keywords: working memory, tDCS, parietal, internal attention, recognition, recall

Introduction

Functional neuroimaging studies have consistently reported that portions of the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) are active during a wide variety of working memory (WM)1 tasks (reviewed in [1, 2]. Similarly, neuropsychological studies have also shown that damage to portions of the PPC lead to WM impairments (reviewed in [1]). The springboard for the current study is a recent finding by our laboratory in which we showed a dissociation in WM performance following PPC damage. Patients with PPC damage have intact performance when WM is tested by recall, but abnormally low performance when WM is tested by old/new recognition. This surprising recall/recognition dissociation was observed across several stimulus types, set sizes, and maintenance durations [3, 4]. Likewise, several older fMRI studies of verbal WM in which the effects of different retrieval conditions were compared found that portions of the PPC were activated when memory was probed by old/new recognition, but not when probed by recall [5–9].

These findings may be interpreted in several ways. For instance, the PPC may subserve certain retrieval processes required only by recognition trials, or may have functions related to making an old/new decision. Our favored interpretation is that the observed recall/recognition dissociation is due to the employment of distinct maintenance strategies. Recall WM paradigms may encourage participants to engage an active rehearsal strategy. PPC patients can adopt this maintenance process and perform normally. Recognition WM paradigms may encourage a less active strategy since participants know that they can rely on familiarity, rather than production, at the retrieval stage. Presumably, this strategy requires attentional refreshing of the items stored in WM, a process that may be damaged after PPC lesions [3, 4].

This distinction between strategies and attentional demands is consistent with a larger theoretical framework termed the internal attention (IA) account. The IA account holds that portions of the PPC contain a domain-general attentional mechanism. This mechanism revives WM representations, a process referred to as attentional refreshing [10, 11]. According to the IA account, WM representations can be “boosted” by returning them to the focus of attention. The notion that attention plays an active role in covert maintenance is consistent with several recent attention-based models of WM (e.g. [12–14]. These models assume the existence of two alternative covert maintenance mechanisms: a material-specific (e.g. verbal) mechanism that relies on rehearsal rather than on attention, and an attentionally mediated refreshing mechanism.

Although this explanation is compelling in its alignment with well-known attentional functions of the parietal cortex, there is one weakness: the data and interpretations depend primarily on lesion studies. Neuropsychological research provides causal links between brain structure and cognitive function. However, the technique suffers from certain limitations. For instance, lesion patients are generally older and may experience additional health problems, experience progressive disease processes, or lesions impinging on multiple brain regions. Perhaps of greatest concern with regard to cognitive performance, patients’ brains may reorganize following trauma and adopt alternative strategies. These factors reduce the ability to generalize findings to the general population and temper our inferential power.

The purpose of the present study was to counter these concerns by replicating our finding of a recall/recognition dissociation in a young healthy population using a different experimental technique: transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). In tDCS, a low, safe level of current is transmitted through the scalp to inhibit (cathodal stimulation) or enhance (anodal stimulation) the likelihood of firing in underlying neural populations [15–17]. Performance on cognitive tasks may be disrupted or enhanced depending on the stimulation parameters and the task demands.

Based on our lesion findings, we predicted that active tDCS (e.g. when compared to sham stimulation) to the right PPC would selectively affect WM performance on blocks of recognition, but not recall, trials. A secondary prediction was that cathodal tDCS would impair recognition WM performance whereas anodal tDCS would improve recognition WM performance [18, 19].

Materials and Methods

Participants

Eleven neurologically normal young adults (age = 25.0, 6 males) participated. Three additional subjects’ data were not included because they performed at ceiling (N = 2) or at floor (N = 1). All experimental protocols were approved by the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Internal Review Board. Participants provided informed consent and they received reimbursement for their time.

Stimulation Protocol

There were three stimulation conditions: anodal, cathodal, and sham. No separate baseline condition was included as identical results between sham and baseline have previously been reported [20]. Conditions were tested on different days and order was counterbalanced between subjects. In all conditions one electrode was placed on the scalp over the right inferior parietal cortex at position P4 (International 10–20 EEG system) while the reference electrode was placed over the left cheek. This site was chosen because it is off of the head and thus less likely to affect a response in the brain. For anodal stimulation, the anode electrode was placed over P4 and for cathodal stimulation the electrodes were reversed, such that the cathode was placed over P4. During sham stimulation, anodal or cathodal placement was randomly applied to the P4 location. Participants were unaware of the polarity of stimulation [21] and the experimental predictions. During debriefing, several participants incorrectly guessed which day they received sham stimulation, suggesting the polarity of the stimulation was blinded.

Stimulation consisted of single continuous direct current delivered by a battery-driven continuous current stimulator (Magstim Eldith 1 Channel DC Stimulator Plus, Magstim Company Ltd, Whitland, Wales). Current was delivered through two electrodes housed in 5 × 7 cm2 saline-soaked sponges. During cathodal and anodal sessions, 1.5 mA current was applied for 10 minutes. During sham sessions, participants received pseudo-stimulation in which the current lasted for 20 seconds at the beginning and at the end of the stimulation time. The sham condition provides the temporary itching sensation but little actual current. Immediately following the stimulation, the electrodes were removed and participants began performing the task.

Stimuli and Task Design

The visual stimuli were 20 colorized drawings of common objects (e.g. nail, pig, clock) [22]. The stimuli were approximately 20 cm × 10 cm.

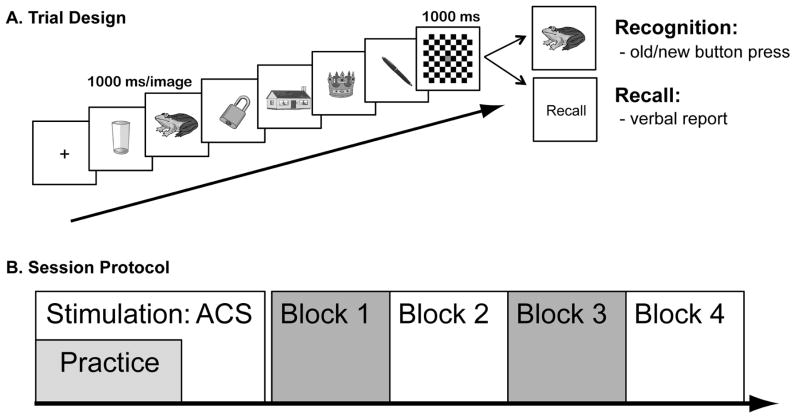

The session began with a practice block of 30 old/new recognition WM trials during stimulation. Recognition trials alone were practiced because only a button press response was required. This eliminated any articulatory movements required by the verbal recall response that might have displaced the electrodes. After ten minutes of stimulation the electrodes were removed and the four experimental trial blocks began. The beginning of recognition and recall trials began identically (see Figure 1A). A series of six images was presented sequentially (1000 ms per image) at central fixation. Next, a checkerboard mask was presented for 1000 ms, during which time the memory set was maintained. At this point, recall and recognition trials diverged. During recall blocks, participants were required to verbally report the names of the items they had observed. Responses were recorded using GarageBand software (Apple Inc, Cupertino, CA) and transcribed off-line. During recognition blocks a seventh probe image appeared and the task was to make an old/new button press response based on whether the probe had been in the memory set or not.

Figure 1.

(A) Trial design. During each trial, six pictures were presented (1000 ms/image), followed by a delay (1000 ms). During recognition blocks, a seventh probe image then appeared and participants judged whether it had been part of the memory set. During recall trials, participants were cued to say the names of all remembered items. (B) Session Protocol. After the electrodes were placed on the participant’s head, the session began. Participants first performed a block of practice trials during the anodal (A), cathodal (C) and sham (S) sessions. Electrodes were then removed and the first of four trial blocks of alternating trial types began.

There were two 20-trial blocks of recognition trials alternating with two 10-trial blocks of recall trails per session (see Figure 1B). The order of recognition and recall blocks was counterbalanced across sessions; each block lasted 3–5 minutes. After each block of trials, participants provided a confidence judgment on a scale of 1–6.

Analysis

Our primary dependent measure was accuracy. Corrected recognition (hit rate minus false alarm rate) was the measure used on old/new recognition trials; raw accuracy was the measure used on recall trials. Initial analyses used separate repeated measures analysis of variance for recognition and recall with two factors: block (first, second) and stimulation session (anodal, cathodal, sham). Data were examined with separated repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for recognition and recall blocks with one factor: stimulation session (anodal, cathodal, sham).

Results

Since no differences were observed between the first and second blocks of each task (Accuracy: recognition: F1, 10 < .01, p = .99, recall: F1, 10 = 1.52, p = .25; Reaction Time: recognition: F1, 10 = 2.37, p = .16, recall: F1, 10 = .93, p = .36) the data were collapsed across block. Reaction time data were examined and no significant effects were observed (recognition: F2, 20 = .12, p = .89; recall: F2, 20 = .47, p = .63). No subject reported mental fatigue or an inability to concentrate throughout the study.

Recognition WM

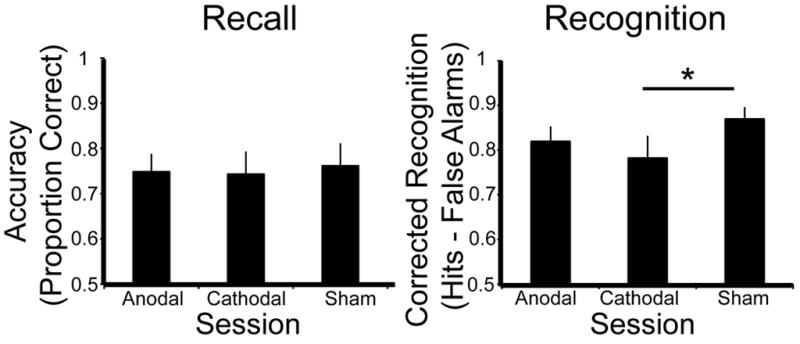

There was a significant main effect of stimulation session on recognition WM performance (F 2, 20 = 3.46, p = .05); see Figure 2. Pairwise comparisons found that the main effect was driven by the significant WM impairment under cathodal stimulation relative to sham (p = .016). Anodal stimulation did not significantly impair recognition WM performance relative to sham (p = .12). There was no statistically significant difference between the anodal and cathodal sessions (p = .37). Participants appeared to be unaware of the deleterious effects of stimulation on performance: when confidence ratings were assessed, there were no significant differences between stimulation conditions (F2, 20 = .39, p = .68).

Figure 2.

Recall WM accuracy (left) and Recognition WM corrected recognition (hits-false alarms; right) for each condition (anodal, cathodal and sham). Lines in the right panel indicate significantly different pairwise comparisons, asterisks indicate a significance level of p < .05.

Hit rates and false alarm rates were subjected to separate ANOVAs to determine whether the significant effect of cathodal tDCS was due to shifting hit or false alarm rates. There was a marginal effect of session (cathodal, sham) on hit rate (F1, 10 = 3.98, p = .07) but no effect of session on false alarm rate (F1, 10 = 1.64, p = .23). Instead, tDCS stimulation of the right PPC appears to cause an effect by reducing the hit rate during the cathodal stimulation session.

Recall WM

In contrast to the recognition data, there was no main effect of stimulation session on recall performance (F 2, 20 = .25, p = .78 see Figure 2). Confidence ratings were similarly unaffected by stimulation (F2, 20 = .71, p = .51).

Discussion

We applied tDCS over the right inferior parietal cortex while subjects performed an object WM task probed by recall or recognition. Our primary prediction was confirmed: tDCS to right inferior parietal cortex selectively impaired WM probed by old/new recognition whereas recall WM performance was unaffected. A more specific prediction based on previous tDCS studies of WM was partially confirmed. We predicted that anodal stimulation would improve recognition WM and cathodal stimulation would impair recognition WM. We observed that cathodal stimulation did impair recognition, but anodal stimulation had no significant effect on recognition performance.

This prediction was shaped by a range of motor and cognitive findings showing that anodal tDCS can improve performance in healthy and patient groups. For example, in the motor literature, anodal stimulation of primary motor cortex decreases inhibition and enhances cortical excitability [23, 24], even improving motor function in Parkinson’s disease patients [25]. In the depression literature, anodal stimulation of left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex temporarily alleviated symptoms in the clinically depressed [26, 27]. However, anodal and cathodal effects do not always oppose each other in the motor literature. There are examples from the motor literature demonstrate effects isolated to anodal or cathodal stimulation. First, anodal stimulation to primary motor cortex improved performance on a serial reaction time task whereas no effects were observed following cathodal stimulation or stimulation of premotor or prefrontal cortex sites [28]. Second, cathodal stimulation alone to area V5 improved performance in a visuomotor tracking task [15]. It has also been shown that the task itself (e.g. passive, cognitive, motor) may shape and influence tDCS effects [29]. In short, it is simplistic to expect cathodal-impairment, anodal-improvement in tDCS paradigms.

The small WM-tDCS literature is also inconsistent. Several studies have reported that anodal tDCS to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) improves performance on verbal n-back tasks [18, 19, 26, 30, 31].2 However, two studies using Sternberg WM tasks and bilateral DLPFC stimulation reported impaired performance after either anodal or cathodal stimulation [27, 32]. In sum, the WM literature indicates that anodal stimulation of the left DLPFC can improve accuracy on verbal n-back WM tasks but other WM tasks and stimulation sites are not associated with WM improvement.

Our study is the first to assess the effects of tDCS stimulation of the right PPC on WM performance. However, there are several WM studies in which transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) was used to disrupt superior PPC function. These studies reported decreased WM for letter alphabetization [33] and spatial location WM [34–37]. Our study is the first to show that object recognition WM is impaired following cathodal stimulation to the PPC.

Predictions of the IA Account and Available Evidence

The IA account discussed earlier predicts that damaging portions of the PPC will impair WM performance on tasks taxing the attentional functions of the PPC. Several categories of WM tasks meet this criteria: (1) most old/new recognition tasks because participants may adopt a less onerous ‘wait and see’ approach that relies on attentional refreshing rather than a taxing verbal rehearsal strategy (for discussion see [11]; (2) WM tasks requiring information manipulation or dual task performance because these tasks demand rapid shifts of attention regardless of retrieval task; (3) WM tasks using difficult-to-rehearse stimuli (e.g. spatial location); and (4) attentional shifting tasks. In the following section we review findings that relevant to these predictions.

First, our previous data showed that unilateral or bilateral PPC lesions impaired performance on old/new recognition tasks [4, 38]. Likewise, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) designed to disrupt the superior parietal lobe can reduce WM for both passively maintaining letters and when manipulating letters in an alphabetization task as tested by old/new recognition [33]. The present tDCS data show that a second type of disruptive stimulation, cathodal tDCS, to the right PPC decreased WM performance for objects when tested by old/new recognition.

Second, TMS disruption of the superior parietal lobe can impair WM on tasks requiring information manipulation [33]. Consistent with these findings, patients with unilateral superior parietal lobe lesions are impaired on tasks requiring manipulation of information such as the backward digit-span, or n-back tasks, but they perform normally on WM tasks requiring the maintenance of easily rehearsed information, such as forward digit span [39].

Third, numerous studies of patients with right PPC lesions have reported the existence of spatial WM deficits on both recall and recognition tasks (reviewed in [1]. Spatial attributes are difficult to verbalize and rehearse thus, patients with PPC damage may be forced to rely on a damaged attention-based maintenance circuit.

Fourth, the IA account predicts that disabling the PPC will degrade some attentional subprocesses, as well as WM. Of the three published reports in which tDCS was used to modulate attention, only one stimulated the PPC. In this study the left PPC (P3, the left homologue of P4) received tDCS while participants performed an attentional shifting task. Participants were cued to report either the local or global feature of Navon letters [40]. The key comparison was between reaction times on the ‘shift’ trials compared to the non-shift trials. The results showed that both anodal and cathodal tDCS slowed attentional switching [41]. This finding lends credence to the possibility that tDCS to the right PPC, a structure generally associated with attention, may also disrupt attentional processes in the current object recognition WM task.

Finally, as noted, the IA model predicts that PPC disruption should not impair WM performance when a material-specific rehearsal mechanism, bypassing attentional maintenance, can be used to maintain information. Digit span, and similar immediate recall tasks lacking a manipulation requirement are examples. Several neuropsychological studies support this prediction [4, 38].

Limitations and Conclusions

One limitation of our study, and of tDCS studies in general, is that there is limited spatial specificity. We targeted the right PPC, but the effects are somewhat dispersed. Although we assume that the observed effects were due to local modulations of cortical excitability, it is possible that tDCS effects emerged from the modulation of synchronized activity in frontoparietal networks as a whole (for discussion see [42]. Network effects of brain stimulation have been found in studies combining tDCS with PET neuroimaging [43, 44]. However, if network effects were responsible for poor recognition WM performance in the cathodal condition, we would have anticipated observing altered performance for the anodal recognition condition as well – and this was not found.

In summary, we successfully replicated the intact WM recall/impaired WM recognition dissociation first observed in patients with parietal lesions [4, 38]. This replication assuages concerns that our previous results were due to a peculiar patient group or due to brain reorganization following trauma.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jennifer Benson for administrative help. We thank Jason Chein, Roy Hamilton, Peter Turkeltaub, and Jared Medina for helpful comments and suggestions. This research was supported by NRSA NS059093 to Marian Berryhill.

Footnotes

The terms “short-term memory” (STM) and “working memory” (WM) refer to different things; the former emphasizes the storage aspect of memory and the latter emphasizes storage and manipulation of information held in memory. Although the distinction between storage and manipulation is of theoretical interest, in practice, the terms STM and WM have often been used somewhat interchangeably. Here, we decided that “working memory” is a more neutral and ubiquitous term.

In these cases the reference electrode was on the right prefrontal cortex, thus each participant received bilateral stimulation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Olson IR, Berryhill M. Some surprising findings on the involvement of the parietal lobe in human memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;91:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wager TD, Smith EE. Neuroimaging studies of working memory: a meta-analysis. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2003;3(4):255–274. doi: 10.3758/cabn.3.4.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berryhill ME, Chein JM, Olson IR. At the intersection of attention and memory: the mechanistic role of the posterior parietal lobe in working memory. (submitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berryhill ME, Olson IR. Is the posterior parietal lobe involved in working memory retrieval? Evidence from patients with bilateral parietal lobe damage. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(7):1775–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker JT, Mintun MA, Diehl DJ, Dobkin J, Martidis A, Madoff DC, DeKosky ST. Functional neuroanatomy of verbal free recall: A replication study. Hum Brain Mapp. 1994;1:284–292. doi: 10.1002/hbm.460010406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chein JM, Fiez JA. Dissociation of verbal working memory system components using a delayed serial recall task. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11(11):1003–1014. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.11.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiez JA, Raife EA, Balota DA, Schwarz JP, Raichle ME, Petersen SE. A positron emission tomography study of the short-term maintenance of verbal information. J Neurosci. 1996;16(2):808–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00808.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grasby PM, Frith CD, Friston KJ, Bench C, Frackowiak RS, Dolan RJ. Functional mapping of brain areas implicated in auditory--verbal memory function. Brain. 1993;116(Pt 1):1–20. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonides J, Schumacher EH, Smith EE, Koeppe RA, Awh E, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Marshuetz C, Willis CR. The role of parietal cortex in verbal working memory. J Neurosci. 1998;18(13):5026–5034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-05026.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewandowsky S, Oberauer K, Brown GD. No temporal decay in verbal short-term memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(3):120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chein JM, Ravizza SM, Fiez JA. Using neuroimaging to evaluate models of working memory and their implications for language processing. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2003;16:315–339. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cowan N. The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral & Brain Sciences. 2001;24(1):87–114. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x01003922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrouillet P, Camos V. Interference: unique source of forgetting in working memory? Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(4):145–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.002. author reply 146–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewandowsky S, Oberauer K. The word-length effect provides no evidence for decay in short-term memory. Psychon Bull Rev. 2008;15(5):875–888. doi: 10.3758/PBR.15.5.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antal A, Kincses TZ, Nitsche MA, Bartfai O, Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human primary visual cortex by transcranial direct current stimulation: direct electrophysiological evidence. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:702–707. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the humanmotor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol. 2000;527:633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenkranz K, Nitsche MA, Tergau F, Paulus W. Diminution of training-induced transient motor cortex plasticity by weak transcranial direct current stimulation in the human. Neurosci Lett. 2000;296(1):61–63. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Nitsche M, Bermpohl F, Antal A, Feredoes E, Marcolin MA, Rigonatti SP, Silva MT, Paulus W, Pascual-Leone A. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of prefrontal cortex enhances working memory. Exp Brain Res. 2005;166(1):23–30. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohn SH, Park CI, Yoo WK, Ko MH, Choi KP, Kim GM, Lee YT, Kim YH. Time-dependent effect of transcranial direct current stimulation on the enhancement of working memory. Neuroreport. 2008;19(1):43–47. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f2adfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fecteau S, Pascual-Leone A, Zald DH, Liguori P, Theoret H, Boggio PS, Fregni F. Activation of prefrontal cortex by transcranial direct current stimulation reduces appetite for risk during ambiguous decision making. J Neurosci. 2007;27(23):6212–6218. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0314-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gandiga PC, Hummel FC, Cohen LG. Transcranial DC stimulation (tDCS): a tool for double-blind sham-controlled clinical studies in brain stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(4):845–850. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossion B, Pourtois G. Revisiting Snodgrass and Vanderwart’s object pictorial set: the role of surface detail in basic-level object recognition. Perception. 2004;33(2):217–236. doi: 10.1068/p5117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boros K, Poreisz C, Munchau A, Paulus W, Nitsche MA. Premotor transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) affects primary motor excitability in humans. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27(5):1292–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vines BW, Nair DG, Schlaug G. Contralateral and ipsilateral motor effects after transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroreport. 2006;17(6):671–674. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200604240-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Santos MC, Lima M, Vieira AL, Rigonatti SP, Silva MT, Barbosa ER, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A. Noninvasive cortical stimulation with transcranial direct current stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21(10):1693–1702. doi: 10.1002/mds.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boggio PS, Rigonatti SP, Ribeiro RB, Myczkowski ML, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A, Fregni F. A randomized, double-blind clinical trial on the efficacy of cortical direct current stimulation for the treatment of major depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(2):249–254. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707007833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrucci R, Bortolomasi M, Vergari M, Tadini L, Salvoro B, Giacopuzzi M, Barbieri S, Priori A. Transcranial direct current stimulation in severe, drug-resistant major depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;118(1–3):215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nitsche MA, Schauenburg A, Lang N, Liebetanz D, Exner C, Paulus W, Tergau F. Facilitation of implicit motor learning by weak transcranial direct current stimulation of the primary motor cortex in the human. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15(4):619–626. doi: 10.1162/089892903321662994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antal A, Terney D, Poreisz C, Paulus W. Towards unravelling task-related modulations of neuroplastic changes induced in the human motor cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26(9):2687–2691. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jo JM, Kim YH, Ko MH, Ohn SH, Joen B, Lee KH. Enhancing the working memory of stroke patients using tDCS. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(5):404–409. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181a0e4cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boggio PS, Ferrucci R, Rigonatti SP, Covre P, Nitsche M, Pascual-Leone A, Fregni F. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on working memory in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2006;249(1):31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall L, Molle M, Siebner HR, Born J. Bifrontal transcranial direct current stimulation slows reaction time in a working memory task. BMC Neurosci. 2005;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Postle BR, Ferrarelli F, Hamidi M, Feredoes E, Massimini M, Peterson M, Alexander A, Tononi G. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation dissociates working memory manipulation from retention functions in the prefrontal, but not posterior parietal, cortex. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18(10):1712–1722. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.10.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamidi M, Slagter HA, Tononi G, Postle BR. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Affects behavior by Biasing Endogenous Cortical Oscillations. Front Integr Neurosci. 2009;3:14. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.014.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamidi M, Tononi G, Postle BR. Evaluating frontal and parietal contributions to spatial working memory with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Res. 2008;1230:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koch G, Oliveri M, Torriero S, Carlesimo GA, Turriziani P, Caltagirone C. rTMS evidence of different delay and decision processes in a fronto-parietal neuronal network activated during spatial working memory. Neuroimage. 2005;24(1):34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamanaka K, Yamagata B, Tomioka H, Kawasaki S, Mimura M. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Parietal Cortex Facilitates Spatial Working Memory: Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Study. Cereb Cortex. 2009;20(5):1037–1045. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berryhill ME, Olson IR. The right parietal lobe is critical for visual working memory. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(7):1767–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koenigs M, Barbey AK, Postle BR, Grafman J. Superior parietal cortex is critical for the manipulation of information in working memory. J Neurosci. 2009;29(47):14980–14986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3706-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navon D. Forest before trees: The precedence of global features in visual perception. Cognitive Psychology. 1977;9:353–383. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stone DB, Tesche CD. Transcranial direct current stimulation modulates shifts in global/local attention. Neuroreport. 2009;20(12):1115–1119. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832e9aa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sparing R, Mottaghy FM. Noninvasive brain stimulation with transcranial magnetic or direct current stimulation (TMS/tDCS)-From insights into human memory to therapy of its dysfunction. Methods. 2008;44(4):329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sadleir RJ, Vannorsdall TD, Schretlen DJ, Gordon B. Predicted current densities for transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in a realistic head model. Neuroimage. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.052. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lang N, Siebner HR, Ward NS, Lee L, Nitsche MA, Paulus W, Rothwell JC, Lemon RN, Frackowiak RS. How does transcranial DC stimulation of the primary motor cortex alter regional neuronal activity in the human brain? Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22(2):495–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]