Abstract

Single-strand DNA interruptions (SSIs) are produced during the process of base excision repair (BER). Through biochemical studies, two SSI repair subpathways have been identified: a pathway mediated by DNA polymerase β (Pol β) and DNA ligase III (Lig III), and a pathway mediated by DNA polymerase δ/ε (Pol δ/ε) and DNA ligase I (Lig I). In addition, the existence of another pathway, mediated by Pol β and DNA Lig I, has been suggested. Although each pathway may play a unique role in cellular DNA damage response, the functional implications of SSI repair by these three pathways are not clearly understood. To obtain a better understanding of the functional relevance of SSI repair by these pathways, we investigated the involvement of each pathway by monitoring the utilization of DNA ligases in cell-free extracts. Our results suggest that the majority of SSIs produced during the repair of alkylated DNA bases are repaired by the pathway mediated by Pol β and either Lig I or Lig III, although some SSIs are repaired by Pol δ/ε and Lig I. At a cellular level, we found that Lig III over-expression increased the resistance of cells to DNA-damaging agents, while Lig I over-expression had little effect. Thus, repair pathways mediated by Lig III may have a role in the regulation of cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents.

INTRODUCTION

During the process of base excision repair (BER), single-strand DNA interruptions (SSIs) are produced as intermediates (1,2). These SSIs, induced by AP-endonuclease through DNA strand cleavage of 5′ apyrimidinic/apurinic sites, have 3′-hydroxyl and 5′-deoxyribose termini (3). If these SSIs remain unrepaired, they cause cytotoxicity (4). In mammalian cells, these SSIs are repaired by two subpathways.

The first pathway is mediated by DNA polymerase β (Pol β) and DNA ligase III (Lig III) (5–8). This DNA polymerase possesses a deoxyribose lyase activity that removes deoxyribose moieties attached at the 5′ termini of SSIs (9,10). The resulting one-nucleotide gap is filled in by Pol β (6) and the DNA strands are then sealed by Lig III (5,6). This ligase forms a complex with XRCC-1, a factor that also forms a complex with AP-endonuclease and Pol β (5,11–13). Thus, it has been proposed that these enzymes are recruited to DNA damage sites through complex formation with XRCC-1, and that incision of AP sites by AP-endonuclease, DNA polymerization and DNA ligation occur in a coordinated manner (13).

The second pathway is mediated by DNA polymerase δ/ε (Pol δ/ε) (1,14). During the repair process, DNA strands must be removed from the 5′ termini of SSIs, and flap endonuclease-1 (FEN-1) has been demonstrated to have this function (14). The DNA gaps are then filled in by Pol δ/ε, and the repair is completed by DNA ligase I (Lig I) (1,6). A DNA sliding clamp, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), interacts with FEN-1, Pol δ/ε and Lig I (15–17). Thus, the processes of DNA strand cleavage by FEN-1, DNA strand synthesis and DNA ligation probably occur in a coordinated manner (1,6). This second pathway is required for the repair of SSIs that have reduced deoxyriboses attached to the 5′ terminus, as Pol β cannot efficiently remove the reduced deoxyribose with its lyase activity (14). However, this pathway is also involved in the repair of SSIs that have a normal 5′ deoxyribose (14).

In addition, the presence of a third pathway, mediated by Pol β and Lig I, has been suggested (7,8,18). In fact, in a reconstituted BER assay system, SSIs can be repaired by Pol β and Lig I (5).

Although each pathway probably has a role in response to DNA damage in vivo, the functional implications of SSI repair by those three distinct pathways are not clearly understood. One functional difference among these repair pathways could be the efficiency of SSI repair. As AP-endonuclease, Pol β and Lig III can be recruited to the damaged sites through complex formation with XRCC-1, the pathway mediated by Pol β and Lig III is proposed to be more efficient than the pathway mediated by Pol β and Lig I (6,13). However, cells from a patient with an abnormality in Lig I show an increased sensitivity to alkylating agents (19–21), suggesting that, even though the pathway mediated by Lig III may be more efficient, the repair of SSIs by this pathway only is not sufficient for cell survival.

As SSIs are common substrates for those three repair pathways, they may be repaired in a competitive or cooperative manner by these pathways in vivo. However, most biochemical investigations have focused on each individual pathway, and thus the relative involvement of each pathway in SSI repair is not clearly determined. To obtain a better understanding of SSI repair, we investigated whether these pathways are indeed involved in the repair of SSIs by monitoring the utilization of DNA ligases in cell-free extracts. Here we report that all three pathways are in fact involved in the repair of SSIs to a different degree. Our results suggest that the majority of SSIs produced during the repair of alkylated DNA bases are repaired by Pol β with either Lig I or Lig III, although some SSIs are repaired by Pol δ/ε and Lig I. At a cellular level, we found that expression of Lig III increased the resistance of cells to DNA-damaging agents. Thus, repair pathways mediated by Lig III may regulate cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant protein preparation

Human Lig I and Lig III cDNAs, cloned into pET11a (pET11a/L1) and pET16b (pET16b/L3), respectively, were kindly provided by Dr T. Lindahl. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and HMS174 (DE3)pLysS were transformed with pET11a/L1 and pET16b/L3, respectively. The C-terminal histidine-tagged Lig I (14,22) and Lig III (23,24) were induced using 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside. Purification of Lig I and Lig III was carried out using Ni-NTA agarose (1 ml, Qiagen). The purified Lig I and Lig III were stored in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0, 10% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl and 2 mM MgCl2. The activity of the resulting DNA ligases was determined using T4 DNA ligase (Amersham Biosciences) as a standard and expressed in Weiss units.

Cell-free extract preparation

GMO1953C and GMO6315A lymphoblastoid cells, obtained from the Human Mutant Cell Repository (Camden, NJ), were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. HeLa S3 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; high glucose) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics (complete DMEM). Cell-free extracts were prepared following the method of Manley et al. (25). Briefly, cell pellets were treated with an equal volume of hypotonic buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA and 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Then, 4 vols of sucrose–glycerol buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM DTT, 25% sucrose and 50% glycerol were added. Cells were then lysed by addition of ammonium sulfate at a 10% final concentration and centrifuged at 25 000 g for 4 h to remove cellular debris. Proteins contained in the supernatant were precipitated using ammonium sulfate at a final concentration of 80%. After collecting the proteins precipitated by centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended and dialyzed against 25 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 17% glycerol. The resulting extracts were used for cell-free DNA repair assays. As 75% of both HeLa S3 and GM01953C cells used for extract preparation were in the G1 phase [determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; Epics XL, Beckman Coulter) after fixation with 70% ethanol followed by propidium iodide staining], our results are likely to reflect the repair of cells at that stage.

Preparation of DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP intermediates

DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP intermediates were prepared following the method of Prigent et al. (26). Purified DNA ligases were incubated with 1 µM ATP and 117 µCi/ml [α-32P]ATP in 50 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 4 mM DTT and 17% glycerol (L buffer) for 30 min at 30°C. For preparation of cell-free extracts containing DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP intermediates, 9 mg/ml of extract protein was incubated in L buffer at 25°C for 10 min with 0.4 mM pyrophosphate (PPi). The resulting extracts were then dialyzed against L buffer for 2 h at 4°C, followed by incubation at 30°C for 30 min with 1 µM ATP and 117 µCi/ml [α-32P]ATP. Extracts were used for cell-free DNA repair assays.

Western blotting

Extracts (12.5 µg total protein) were denatured at 100°C for 5 min in gel-loading buffer, fractionated by SDS–7.5% PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with either anti-Lig I (mouse polyclonal antibody, 1000-fold dilution), Lig III (mouse polyclonal antibody, 1000-fold dilution) or DNA ligase IV (rabbit polyclonal antibody, 1000-fold dilution) antibodies (Abcam Ltd, Cambridge, UK), followed by incubation with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody. The membrane was then incubated with chemiluminescence reagents. Proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

Cell-free DNA repair assay

Circular plasmid DNAs containing γ-ray-induced SSIs and N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG)-induced DNA damage were prepared as described (27,28). Briefly, supercoiled pBluescript II K/S+ (3.4 mg/ml; Stratagen) in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and 1 mM EDTA was exposed to 50 Gy of γ-rays from a 60Co source (dose rate; 0.51 Gy/min, Gamma Cell 220, Atomic Energy of Canada) at 0°C to convert 10% of the DNA to an open circular form. The plasmids containing single-strand DNA breaks were then purified by two cycles of ethidium bromide–CsCl density gradient centrifugation (27). Under these conditions, the amounts of other oxidized base damage present in these purified plasmids were estimated (using Nth and Fpg proteins) to be 10% of SSI (29). For MNNG treatment, pBluescript II K/S+ (0.2 mg/ml) was incubated with 0.4 mM MNNG for 30 min at 37°C. The treated plasmid was precipitated by ethanol (28). Repair reactions were carried out using 300 ng of treated plasmid DNA, 50 µg of cell-free extracts in a 50 µl reaction mixture containing 50 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.8, 5 mM MgCl2, 70 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.4 mM EDTA, 8 µM dATP, 20 µM of each dCTP, dGTP and dTTP, 2 mM ATP, 40 mM phosphocreatine, 2.5 µg creatine phosphokinase (type I, Sigma) and 2 mM NAD+ at 30°C for 1 h (27). In some reactions, purified DNA ligase was also added. Reactions were terminated by addition of SDS, EDTA and proteinase K. Purified DNA was analyzed by ethidium bromide–1% agarose gel electrophoresis as described (27). Alternatively, reactions were terminated by heating samples at 65°C for 15 min in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 1 mM DTT, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue and 10% glycerol. DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP intermediates were fractionated by SDS–7.5% PAGE. 32P activity was visualized by autoradiography after gel drying.

Purification of cells over-expressing either Lig I or Lig III using colloidal super-paramagnetic microbeads

pMACS KK.II (2.2 µg, Miltenyi Biotec), containing genetically modified mouse H-2KK cDNA, with the mammalian expression construct of either Lig I (4.3 µg, pcDNA 3.1-/GS/Ligase I), Lig III (pcDNA 3.1-/GS/Ligase III, ResGene) or pBluescript K/S+ (4.3 µg) used as a carrier, were mixed with 19.5 µl of Tfx-20 (Promega) in 5.2 ml of serum-free DMEM. As a control, pBluescript K/S+ was transfected instead of the Lig I or Lig III mammalian expression construct. After 15 min of incubation at room temperature, the mixture was added to a 10 cm cell culture dish containing HeLa S3 cells at 80% confluency. These cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. A 25 ml aliquot of complete DMEM was then added, and the cells were further cultured for 24 h. These cells were harvested with trypsin–EDTA and resuspended in 10 ml of complete DMEM. Cells (1 × 107) were spun down, and the pellets were resuspended in 300 µl of complete DMEM and mixed with 40 µl of colloidal super-paramagnetic microbeads coated with anti-H-2KK antibody (MACSelect KK MicroBeads; Miltenyi Biotec). To allow the beads to bind to the H-2KK antigens expressed on cellular surfaces, the suspension was gently mixed for 15 min at room temperature. Then, 1660 µl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 5 mM EDTA (PBE) was added to the cell suspension. MS columns (Miltenyi Biotec), held by a magnet, were pre-equilibrated with 500 µl of PBE. The cell suspension was applied to the column, then washed four times with 500 µl of PBE. Magnetically retained cells were eluted with 1 ml of PBE after removing the magnet. Expression of Lig I or Lig III in retained cells was analyzed by western blotting using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-V5 antibody against a V5 epitope genetically fused to Lig I or Lig III.

Cell survival assay

Purified cells were plated into 6 cm dishes and maintained for 24 h in complete DMEM. The medium was replaced with PBS and the cells were treated with MNNG for 20 min. Then, the PBS containing MMNG was replaced with complete DMEM and the cells were maintained for 2 weeks. Alternatively, cells were exposed to γ-rays (dose rate; 0.18 Gy/s, Gamma Cell 40 Exactor, MDS-Nordion, Canada). The number of surviving cells was determined by counting colonies after Giemsa staining.

RESULTS

Assay design and preparation of cell-free extracts containing DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP intermediates

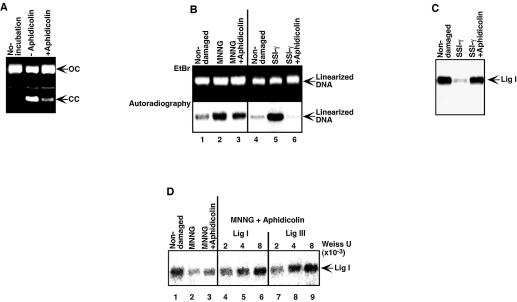

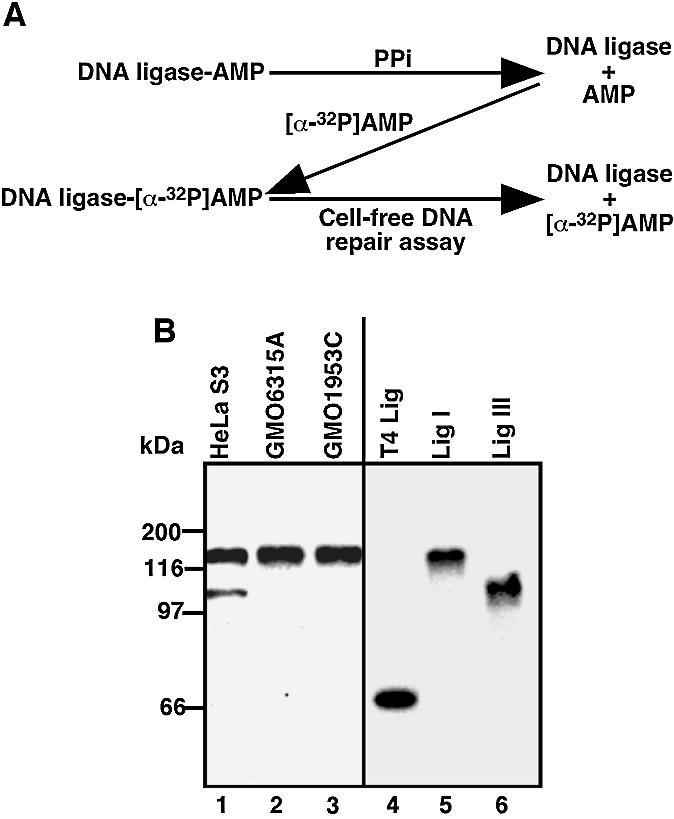

Whole cell-free extracts, used for the study of DNA repair, contain all required factors for BER (27,30). To determine the pathways involved in the repair of SSIs, we first focused on DNA ligases. In the extracts, most of the DNA ligases are present as DNA ligase-AMP intermediates (26). Thus, the extracts were treated with PPi (Fig. 1A) to remove the AMP from the DNA ligases and the PPi was then dialyzed out from the extracts. The dialyzed extracts were incubated with [α-32P]ATP (2 µM) to allow DNA ligases to form intermediates with [α-32P]AMP. Because AMP was removed from DNA ligase by PPi, the specific activity of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP is expected to be similar to that of Lig III-[α-32P]AMP. In crude extracts, 125 and 100 kDa proteins, identified as Lig I and Lig III/DNA ligase IV, are reported to be [α-32P]AMP labeled (31). Consistent with the reports and as shown in Figure 1B, lane 1, proteins showing mobilities similar to recombinant Lig I-[α-32P]AMP (125 kDa, lane 5) and recombinant Lig III-[α-32P]AMP (100 kDa, lane 7), respectively, were visualized in HeLa S3 cell extracts. DNA ligase IV, another DNA ligase involved in non-homologous end joining and V(D)J recombination, shows similar mobility to Lig III (32). However, in lymphoblastoid cell extracts that contain a lower amount of Lig III (7), negligible amounts of [α-32P]AMP-labeled 100 kDa protein were found [Fig. 1B, lane 2 (GM0631A) and lane 3 (GMO1953C)], suggesting that DNA ligase IV may not be efficiently adenylated, as reported (32). In addition, this type of cell-free extract does not support non-homologous end joining (28). Thus, even if DNA ligase IV is [α-32P]AMP labeled, DNA ligase IV is unlikely to have any effect on our analysis. These radiolabeled extracts were then used for cell-free DNA repair assays (Fig. 1A) containing a 1000-fold excess of non-labeled ATP (2 mM) relative to [α-32P]AMP (2 µM). Upon DNA break rejoining, AMP is released from DNA ligase (26). Thus, if DNA ligases- [α-32P]AMP are used for rejoining DNA breaks during the cell-free DNA repair assay, [α-32P]AMP is expected to be released. Therefore, utilization of DNA ligases can be monitored by the reduction of DNA ligases-[α-32P]AMP.

Figure 1.

Assay design and preparation of cell-free extracts containing DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP. (A) Whole cell-free extracts were treated with PPi to remove AMP from DNA ligases. PPi was then dialyzed out and the dialyzed extracts were incubated with [α-32P]ATP to form DNA ligase- [α-32P]AMP. Extracts containing DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP were used for cell-free DNA repair assays. When the DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP is used to rejoin DNA nicks, [α-32P]AMP is released from the DNA ligase. (B) Cell-free extracts containing DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP, recombinant Lig I- [α-32P]AMP, Lig III-[α-32P]AMP and T4 DNA ligase (T4 Lig)-[α-32P]AMP were fractionated by SDS–7.5% PAGE and 32P activity was visualized by autoradiography.

DNA repair assay with cell-free extracts containing Lig I-[α-32P]AMP

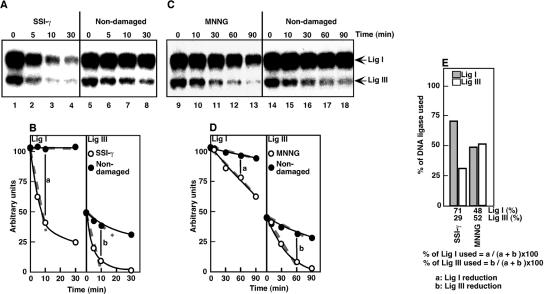

To test whether the amount of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP is reduced in a DNA repair-dependent manner, we used a plasmid containing γ-ray-induced SSIs, which has a well characterized repair process in similar cell-free DNA repair assays (27,28). We previously reported that 40–65% of γ-ray-induced SSIs were repaired within 60 min of incubation (27,28). Consistent with our previous reports, 45% of γ-ray-induced SSIs were repaired in the assay with PPi-treated HeLa S3 cell extracts (see Fig. 4A). Under our assay conditions, the amount of Lig I- [α-32P]AMP was reduced (Fig. 2A, lanes 1–4, and B), while the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP in an assay with non-damaged DNA was negligible (Fig. 2A, lanes 5–8, and B). However, the amount of Lig I was not altered (determined by western blotting with anti-Lig I antibody) by incubation (data not shown), suggesting that the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP occurs in a DNA repair-dependent manner. Thus, the utilization of DNA ligases can be monitored by our assay.

Figure 4.

Effect of aphidicolin on DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP reduction. (A) Cell-free DNA repair assays were carried out with extracts containing DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP in the presence of aphidicolin (80 µg/ml) and [α-32P]dATP (40 µCi/ml). Plasmid DNA containing γ-ray-induced SSIs (γ-SSI) was used as substrate. After the repair reaction, the DNA was purified, fractionated on an ethidium bromide (EtBr)–1% agarose gel and visualized by UV. Open circular DNA (OC) and closed circular DNA (CC) produced by repair of SSIs are indicated. (B) After DNA purification, the DNA was linearized with HindIII, fractionated on an EtBr–1% agarose gel and visualized by UV. The dried gel was exposed to X-ray film to determine the [α-32P]dAMP incorporation into DNA repair patches (autoradiography). (C) To determine the reduction of DNA ligase I-[α-32P]AMP, the reaction mixture was also fractionated on an SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gel and 32P activity was visualized by autoradiography. (D) Assays were carried out with MNNG-treated DNA in the presence of aphidicolin and either Lig I or Lig III. The reaction mixtures were fractionated on an SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gel and 32P activity was visualized by autoradiography to determine the reduction of DNA ligase I-[α-32P]AMP.

Figure 2.

DNA repair-dependent reduction of DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP. (A and C) Cell-free DNA repair assays were carried out with HeLa S3 cell extracts containing DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP. Non-damaged DNA or plasmid DNA containing either γ-ray-induced SSIs (γ-SSI) (A) or alkylated base damage induced by MNNG (C) were used for the assay. After the repair reactions, extracts were fractionated on an SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gel, and 32P activity was visualized by autoradiography. The results shown are from five independent experiments. The standard errors are typically within 5%. (B and D) Quantified data from (A) and (C) are shown in (B) and (D), respectively. The amount of Lig I-[32P]AMP at 0 min was expressed as 100 arbitrary units. (E) The percentage of each DNA ligase used was determined using results shown in (B) and (D). Linear regression lines were drawn (gray dotted lines in B and D). Then time points within the linear range were chosen (10 min for SSI-γ and 60 min for MNNG). The reduced amounts of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP [a] and Lig III-[α-32P]AMP [b] were determined based on linear regression lines. Upon determination, non-specific reduction (non-damaged) was subtracted. The sum of [a] and [b] was calculated as 100%, and the percentage of Lig I and Lig III used was calculated as follows: % of Lig I used = a/(a + b) × 100, and % of Lig III used = b/(a + b) × 100.

DNA repair assay with MNNG-treated plasmid DNA

During cell-free DNA repair assays with MNNG-treated plasmid DNA, we previously demonstrated that alkylated base damage induced by MNNG is removed and converted into SSIs within 5–10 min after initiation of cell-free DNA repair reactions (28). These SSIs are then repaired (28). As shown in Figure 2B (lanes 9–13) and D, the amount of Lig I- [α-32P]AMP was reduced by incubating the HeLa S3 cell extracts with the plasmid DNA containing MNNG-induced alkylated base damage, suggesting that Lig I is used for the repair of SSIs produced during the repair of this damage by BER.

Relative involvement of Lig I and Lig III in DNA repair

In the repair assay conditions, the amount of Lig III- [α-32P]AMP gradually decreased when the HeLa S3 cell extracts were incubated with non-damaged DNA (Fig. 2A, lanes 5–8, and B). A similar reduction was observed when recombinant Lig III-[α-32P]AMP was incubated in the presence of 2 mM ATP, suggesting that this reduction occurs due to the replacement of [α-32P]AMP bound to Lig III by AMP during cell-free DNA repair assay. Despite this reduction, the rate of Lig III-[α-32P]AMP reduction was further increased in the assay with a plasmid containing γ-ray-induced SSIs or MNNG-treated plasmid DNA. This reduction was not due to the degradation of Lig III, as no obvious degradation of Lig III was found by western blotting with anti-Lig III antibody (data not shown), suggesting that Lig III-[α-32P]AMP is also used in the repair of SSIs (Fig. 2A–D). To determine the relative involvement of Lig I and Lig III in SSI repair, we calculated the percentage of Lig I and Lig III used for the repair (see Fig. 2 legend). As shown in Figure 2E, of the total amount of DNA ligases that was used for repair of γ-ray-induced SSIs, Lig I accounts for 71%, suggesting that Lig I plays a major role in the repair of γ-ray induced SSIs, as previously proposed (1). In the case of Lig III, a significant involvement was observed when MNNG-treated plasmid DNA was used (Fig. 2E, ∼50%). Typically, the content of Lig III relative to Lig I is only 30%. Despite this fact, Lig III was probably involved in the repair of ∼50% of SSIs produced during BER. Thus, repair mediated by Pol β and Lig III indeed has a higher efficiency of SSI repair, as suggested (6,13,33), than repair mediated by Pol β and Lig I. However, these results also suggest that SSIs are still repaired by the repair pathway mediated by Lig I.

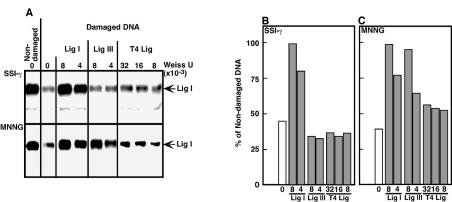

Effect of addition of purified DNA ligases on the reduction of DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP

We determined the DNA ligases involved in the repair of SSIs by addition of purified DNA ligases to the cell-free DNA repair assay with extracts containing DNA ligases- [α-32P]AMP. Cell-free reactions were carried out for 60 min and the amount of Lig III-[α-32P]AMP was reduced to background levels (Fig. 3A). Under these conditions, the amount of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP was reduced in a DNA repair-dependent manner as shown in Figure 2A and B. If the added DNA ligases can compete with Lig I-[α-32P]AMP, the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP is expected to be inhibited. In fact, 4 U of purified Lig I was sufficient to inhibit the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP (Fig. 3A and B). On the other hand, even 32 U of T4 DNA ligase did not inhibit the reduction. Interestingly, added Lig III did not show any effect on the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP, consistent with our finding (Fig. 2A and B) that Lig I plays a major role in the repair of γ-ray-induced SSIs.

Figure 3.

Effect of DNA ligase addition on the DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP reduction. (A) Cell-free DNA repair assay was carried out for 60 min with HeLa S3 cell extracts containing DNA ligase-[α-32P]AMP. Plasmid DNA containing either γ-ray-induced SSIs (γ-SSI) or alkylated base damage induced by MNNG was used for the assay. The reactions also contained Lig I, Lig III or T4 DNA ligase (T4 Lig). After the repair reaction, the mixtures were fractionated on an SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gel, and 32P activity was visualized by autoradiography. Alternatively, 32P activities were measured with an AlphaImager (Packard) and quantified results are shown in (B) (γ-SSI) and (C) (MNNG). The results shown are from one of four independent experiments. The amount of Lig I-[32P]AMP (non-damaged DNA) was calculated as 100%.

In the case of alkylating base damage induced by MNNG, 4 U of either Lig I or Lig III inhibited the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP (Fig. 3A and C), suggesting that SSIs produced by BER during the repair of alkylated base damage are repaired throught the action of Lig III in addition to Lig I. Furthermore, these results suggest that, for the repair of SSIs, Lig I can be replaced by Lig III.

Cell-free DNA repair assay in the presence of aphidicolin

Repair mediated by both Pol β and Pol δ/ε can be terminated by Lig I. Thus, we carried out cell-free repair assays under conditions in which Pol δ/ε-mediated repair is inhibited by aphidicolin. As shown in Figure 4A, aphidicolin inhibited the conversion of open circular plasmid containing γ-ray-induced single-strand DNA breaks to the closed circular form, forms that are due to the repair of SSIs. Over 95% of [α-32P]dAMP incorporation into plasmid DNA containing γ-ray-induced SSIs due to DNA repair synthesis was also inhibited by aphidicolin (Fig. 4B, lane 5 versus 6). In addition, aphidicolin inhibited the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that γ-ray-induced SSIs are repaired mainly by Pol δ/ε.

In contrast to the repair of γ-ray-induced SSIs, aphidicolin had little effect on the incorporation of [α-32P]dAMP (20% reduction) into MNNG-treated plasmid DNA (Fig. 4B, lane 2 versus 3), suggesting that 80% of the repair is mediated by Pol β and 20% by Pol δ/ε. Under assay conditions in which aphidicolin is present, the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP was only slightly affected (Fig. 4D, lane 2 versus 3). Thus, the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP is likely to be due to the repair of SSIs by Pol β and Lig I. We then carried out cell-free DNA repair assays with aphidicolin and tested the effect of purified Lig I or Lig III addition. As shown in Figure 4D (lanes 4–6), the reduction of Lig I-[α-32P]AMP was inhibited by the addition of Lig I. Similarly, addition of Lig III also inhibited the reduction (Fig. 4D, lanes 7–9). Therefore, SSIs produced during the repair of alkylated base damage by BER are repaired mainly by Pol β, and the repair can be terminated by either Lig I or Lig III.

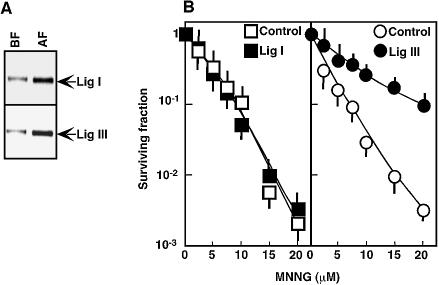

Expression of Lig III and cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents

Our results thus far suggest that both Lig I and Lig III can terminate repair of SSIs mediated by Pol β. In cells, the amount of Lig III relative to Lig I is typically ∼30%, and in lymphoblastoid cells it is <5% (Fig. 1B) (7). Thus, an altered Lig III content in cells may affect the relative involvement of repair mediated by Lig III in the repair of SSIs. At a biochemical level, however, an increased content in Lig III is unlikely to affect the repair rate, as addition of Lig I or Lig III to a cell-free repair assay did not show any major effect on the rate of DNA break repair [data not shown and Satoh et al. (28)]. However, the cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents is altered by the impairment of one particular pathway for the repair of SSIs (12,19–21). Thus, we then investigated the effect of an altered content of Lig III on cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents. For this purpose, HeLa S3 cells over-expressing Lig III were exposed to MNNG. After transfection of a Lig III mammalian expression construct, cells expressing Lig III were purified with the pMACSelect KK.II system (see Materials and Methods) that allowed a 5-fold concentration of Lig III-expressing cells (20% positive cells to 95%) (Fig. 5A). Purified cells were then treated with MNNG to determine the effect of Lig III over-expression on cell survival. As shown in Figure 5B (Control), ∼90% of control cells were killed by 7.5 µM MNNG. On the other hand, Lig III-over-expressing cells showed an increased resistance to MNNG, and 20 µM MNNG was required to kill 90% of these cells. As a control, Lig I was also over-expressed (Fig. 5A) and exposed to MNNG or γ-rays. However, Lig I over-expression did not cause any major change in cellular sensitivity to MNNG or γ-rays (data not shown). Thus, cells possibly already contain a sufficient amount of endogenous Lig I (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that expression of Lig III confers cellular resistance to MNNG.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity of Lig I or Lig III over-expressing cells to MNNG. (A) Either pcDNA 3.1-/GS/ligase I or pcDNA 3.1-/GS/ligase III was co-transfected with pMACS KK.II in HeLa S3 cells and, 24 h post-transfection, H-2KK-positive cells were separated using colloidal super-paramagnetic microbeads coated with anti-H-2KK antibodies (see Materials and Methods). Expression of Lig I or Lig III in non-separated (BF) and purified (AF) HeLa S3 cells was then examined by western blotting with an anti-V5 antibody against a V5 epitope fused to Lig I or Lig III. (B) Cells expressing Lig I or Lig III were cultured for 12 h and then treated with MNNG for 20 min. These treated cells were cultured for 2 weeks to allow colonies to form. The number of colonies was determined after Giemsa staining. Standard deviations are shown.

DISCUSSION

Through biochemical investigations, two SSI repair pathways have been identified and an additional one has been suggested, but the relative involvement of each pathway in SSI repair has not been clearly determined. In this report, we demonstrated that, although some SSIs are repaired by Pol β and Lig I, γ-ray-induced SSIs were predominantly repaired by Pol δ/ε and Lig I. The 3′-phosphate or phosphoglycolate groups, produced by γ-ray irradiation, must be removed by AP-endonuclease or polynucleotide kinase to repair SSIs (34–36). Thus, FEN-1 may initiate DNA strand cleavage prior to the initiation of DNA polymerization, favoring a repair mediated by Pol δ/ε and Lig I. On the other hand, alkylated DNA bases are repaired by Pol β and either Lig I or Lig III. In terms of biochemical activity of DNA repair, however, the lack of one or two pathways does not seem to have a major effect on the rate of SSI repair. Extracts prepared from 46BR cells, impaired in Lig I, can repair uracils at a rate almost identical to extracts from normal cells (26). Thus, even though repair pathways mediated by Lig I are impaired in 46BR cells, SSI repair can be carried out by a pathway mediated by Lig III. Similarly, the lack of the Pol β-mediated pathway does not have a major effect on the repair of DNA damage, as extracts prepared from Pol β knockout cells show a normal repair rate of oxidized base damage (37). Furthermore, the absence of Lig III is unlikely to have an effect on the rate of SSI repair since extracts from lymphoblastoid cells, containing significantly less Lig III, do not show any impairment of either Pol β or Pol δ/ε pathways. Addition of Lig I or Lig III to repair assays with lymphoblastoid cell extracts indeed does not alter the rate of DNA repair [data not shown and Satoh et al. (28)]. These observations suggest that one particular pathway can act as a backup pathway for others. Various protein–protein interactions, including XRCC-1 with Lig III (6,8), XRCC-1 with Pol β (6,8) and PCNA with Pol δ/ε (38), along with repair of SSI by Pol β and FEN-1 (39), may thus facilitate the repair by this backup mechanism. Due to the presence of this mechanism, however, unique experimental settings seem to be required to observe the specific role of DNA polymerases or DNA ligases in SSI repair. For example, Lig I abnormality can only be observed when AP sites, designed not to be repaired by the pathways mediated by Pol β, are used (40). The use of reduced AP sites is required to detect the DNA polymerase switching from Pol β to Pol δ/ε (41). The role of Pol β in oxidative DNA damage repair can be detected when Pol β –/– cell extracts, in which Pol δ/ε activity is inhibited, are used, although a lack of Pol β does not have a major effect on cellular sensitivity to ionizing radiation (42). Nevertheless, if one particular pathway is active enough to repair SSIs even when other pathways are impaired, the repair rate of SSIs may not be affected significantly by these impairments. Therefore, the functional roles of SSI repair by those three pathways must be related to other events, such as cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents.

Regarding cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, we recently reported that long repair-patch synthesis increases risks of double-strand DNA break (DSB) formation. DSBs are the most lethal type of DNA damage (43,44), occurring when two closely spaced damaged sites in DNA are produced on opposite DNA strands. The repair of this damage by BER results in SSI formation. If the distance between two sites of DNA damage is long enough to maintain the DNA duplex (a denaturation temperature >37°C), SSI formation itself cannot cause DSB formation. We demonstrated that initiation of DNA strand cleavage in a 5′ to 3′ direction by FEN-1, an enzyme involved in the repair pathway mediated by Pol δ/ε, results in reduction of the DNA duplex length between these SSIs, and leads to the denaturation of DNA and ultimately to DSB formation (44). Thus, SSI repair by Pol δ/ε and Lig I (often referred to as long-patch BER) is probably associated with a higher risk of causing DSB formation. In this context, SSI repaired by Pol β has less risk of forming DSBs as this repair is completed by synthesis of short repair patches. Thus, cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents may be controlled or affected by the relative involvement of the pathways mediated by Pol δ/ε and Lig I or by Pol β.

Alternatively, Lig III itself may play a role in the regulation of cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, as a recent report demonstrated that stabilization of Lig III results in an increased resistance of cells to apoptotic induction (45) and we found that cells over-expressing Lig III were less sensitive to MNNG (Fig. 5). Because Lig III forms a complex with XRCC-1, a factor that also interacts with Pol β, AP-endonuclease, polynucleotide kinase and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (5,11,12,46,47), an increased resistance of Lig III-over-expressing or Lig III-stabilized cells to DNA-damaging agents is probably related to complex formation and the interaction of this complex with other enzymes. In particular, the mechanistic link between Lig III–XRCC-1 complex formation and an increased resistance of cells by over-expression of Lig III can be explained by the interaction of XRCC-1 with an abundant nuclear enzyme, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (48). In response to DNA break formation, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 catalyzes a post-translational modification of proteins with ADP-ribose polymers (48). However, it has been reported that the interaction of XRCC-1 with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 leads to the inhibition of ADP-ribose polymer formation (46). Recently, Yu et al. demonstrated that ADP-ribose polymers play a critical role in the induction of cell death by apoptosis (49). One of the factors inducing apoptosis, AIF, is translocated from the cytoplasm into the nucleus to activate apoptosis, and this translocation process depends on ADP-ribose polymer formation (49). Because the suppression of ADP-ribose polymer formation inhibits AIF-mediated apoptotic induction (49), inhibition of ADP-ribose polymer formation by the Lig III–XRCC-1 complex may have a similar effect. Thus, by this mechanism, over-expression or stabilization of Lig III may confer cellular resistance to DNA-damaging agents.

Finally, the cellular content of Lig III relative to Lig I and of Lig III mRNA relative to Lig I mRNA varies significantly among cell types (50); for example, in lymphoblastoid cells, only small amounts of Lig III are found compared with HeLa S3 cells (Fig. 1). It has been shown that lymphoblastoid cells are relatively sensitive to DNA-damaging agents (51,52). Lig III mutant cells are also sensitive to DNA-damaging agents (12,53). On the other hand, over-expression (Fig. 5A) or stabilization of Lig III (45) increased cellular resistance to DNA-damaging agents, while Lig I over-expression did not alter cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents (Fig. 5B). Thus, it is plausible that, while repair mediated by Lig I acts as a constitutive repair pathway for SSIs, repair completed by Lig III may play a role in the regulation of cell type-specific sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Sachiko Sato for critical reading of this manuscript and Ann Rancourt for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and partly by the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) for M.S.S. M.S.S. is a salary support award recipient from NCIC and CIHR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoeijmakers J.H. (2001) Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature, 411, 366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindahl T. (1993) Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature, 362, 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seeberg E., Eide,L. and Bjoras,M. (1995) The base excision repair pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci., 20, 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeb L.A. (1985) Apurinic sites as mutagenic intermediates. Cell, 40, 483–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubota Y., Nash,R.A., Klungland,A., Schar,P., Barnes,D.E. and Lindahl,T. (1996) Reconstitution of DNA base excision-repair with purified human proteins: interaction between DNA polymerase β and the XRCC1 protein. EMBO J., 15, 6662–6670. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindahl T. and Wood,R.D. (1999) Quality control by DNA repair. Science, 286, 1897–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindahl T. and Barnes,D.E. (1992) Mammalian DNA ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 61, 251–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomkinson A.E., Chen,L., Dong,Z., Leppard,J.B., Levin,D.S., Mackey,Z.B. and Motycka,T.A. (2001) Completion of base excision repair by mammalian DNA ligases. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 68, 151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad R., Beard,W.A., Chyan,J.Y., Maciejewski,M.W., Mullen,G.P. and Wilson,S.H. (1998) Functional analysis of the amino-terminal 8-kDa domain of DNA polymerase beta as revealed by site-directed mutagenesis. DNA binding and 5′-deoxyribose phosphate lyase activities. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 11121–11126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto Y. and Kim,K. (1995) Excision of deoxyribose phosphate residues by DNA polymerase beta during DNA repair. Science, 269, 699–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caldecott K.W., Aoufouchi,S., Johnson,P. and Shall,S. (1996) XRCC1 polypeptide interacts with DNA polymerase β and possibly poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and DNA ligase III is a novel molecular ‘nick-sensor’ in vitro.Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 4387–4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldecott K.W., McKeown,C.K., Tucker,J.D., Ljungquist,S. and Thompson,L.H. (1994) An interaction between the mammalian DNA repair protein XRCC1 and DNA ligase III. Mol. Cell Biol., 14, 68–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vidal A.E., Boiteux,S., Hickson,I.D. and Radicella,J.P. (2001) XRCC1 coordinates the initial and late stages of DNA abasic site repair through protein–protein interactions. EMBO J., 20, 6530–6539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klungland A. and Lindahl,T. (1997) Second pathway for completion of human DNA base excision-repair: reconstitution with purified proteins and requirement for DNase IV (FEN1). EMBO J., 16, 3341–3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosfield D.J., Mol,C.D., Shen,B. and Tainer,J.A. (1998) Structure of the DNA repair and replication endonuclease and exonuclease FEN-1: coupling DNA and PCNA binding to FEN-1 activity. Cell, 95, 135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes X.V. and Burgers,P.M. (2000) Two modes of FEN1 binding to PCNA regulated by DNA. EMBO J., 19, 3811–3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X., Li,J., Li,X., Hsieh,C.L., Burgers,P.M. and Lieber,M.R. (1996) Processing of branched DNA intermediates by a complex of human FEN-1 and PCNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 2036–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasad R., Singhal,R.K., Srivastava,D.K., Molina,J.T., Tomkinson,A.E. and Wilson,S.H. (1996) Specific interaction of DNA polymerase β and DNA ligase I in a multiprotein base excision repair complex from bovine testis. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 16000–16007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Squires S. and Johnson,R.T. (1983) UV induces long-lived DNA breaks in Cockayne’s syndrome and cells from an immunodeficient individual (46BR): defects and disturbance in post incision steps of excision repair. Carcinogenesis, 4, 565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teo I.A., Arlett,C.F., Harcourt,S.A., Priestley,A. and Broughton,B.C. (1983) Multiple hypersensitivity to mutagens in a cell strain (46BR) derived from a patient with immuno-deficiencies. Mutat. Res., 107, 371–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teo I.A., Broughton,B.C., Day,R.S., James,M.R., Karran,P., Mayne,L.V. and Lehmann,A.R. (1983) A biochemical defect in the repair of alkylated DNA in cells from an immunodeficient patient (46BR). Carcinogenesis, 4, 559–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrari G., Rossi,R., Arosio,D., Vindigni,A., Biamonti,G. and Montecucco,A. (2003) Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of human DNA ligase I at CDK sites. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 37761–37767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leppard J.B., Dong,Z., Mackey,Z.B. and Tomkinson,A.E. (2003) Physical and functional interaction between DNA ligase III α and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 in DNA single-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol., 23, 5919–5927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nash R.A., Caldecott,K.W., Barnes,D.E. and Lindahl,T. (1997) XRCC1 protein interacts with one of two distinct forms of DNA ligase III. Biochemistry, 36, 5207–5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manley J.L., Fire,A., Samuels,M. and Sharp,P.A. (1983) In vitro transcription: whole-cell extract. Methods Enzymol., 101, 568–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prigent C., Satoh,M.S., Daly,G., Barnes,D.E. and Lindahl,T. (1994) Aberrant DNA repair and DNA replication due to an inherited enzymatic defect in human DNA ligase I. Mol. Cell Biol., 14, 310–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satoh M.S. and Lindahl,T. (1992) Role of poly(ADP-ribose) formation in DNA repair. Nature, 356, 356–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satoh M.S., Poirier,G.G. and Lindahl,T. (1993) NAD(+)-dependent repair of damaged DNA by human cell extracts. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 5480–5487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satoh M.S., Jones,C.J., Wood,R.D. and Lindahl,T. (1993) DNA excision-repair defect of xeroderma pigmentosum prevents removal of a class of oxygen free radical-induced base lesions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 6335–6339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wood R.D., Robins,P. and Lindahl,T. (1988) Complementation of the xeroderma pigmentosum DNA repair defect in cell-free extracts. Cell, 53, 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei Y.F., Robins,P., Carter,K., Caldecott,K., Pappin,D.J., Yu,G.L., Wang,R.P., Shell,B.K., Nash,R.A., Schar,P. et al. (1995) Molecular cloning and expression of human cDNAs encoding a novel DNA ligase IV and DNA ligase III, an enzyme active in DNA repair and recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 3206–3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robins P. and Lindahl,T. (1996) DNA ligase IV from HeLa cell nuclei. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 24257–24261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cappelli E., Taylor,R., Cevasco,M., Abbondandolo,A., Caldecott,K. and Frosina,G. (1997) Involvement of XRCC1 and DNA ligase III gene products in DNA base excision repair. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 23970–23975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winters T.A., Weinfeld,M. and Jorgensen,T.J. (1992) Human HeLa cell enzymes that remove phosphoglycolate 3′-end groups from DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 2573–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jilani A., Ramotar,D., Slack,C., Ong,C., Yang,X.M., Scherer,S.W. and Lasko,D.D. (1999) Molecular cloning of the human gene, PNKP, encoding a polynucleotide kinase 3′-phosphatase and evidence for its role in repair of DNA strand breaks caused by oxidative damage. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 24176–24186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karimi-Busheri F. and Weinfeld,M. (1997) Purification and substrate specificity of polydeoxyribonucleotide kinases isolated from calf thymus and rat liver. J. Cell Biochem., 64, 258–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allinson S.L., Dianova, II and Dianov,G.L. (2001) DNA polymerase β is the major dRP lyase involved in repair of oxidative base lesions in DNA by mammalian cell extracts. EMBO J., 20, 6919–6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelman K. (1997) PCNA: structure, functions and interactions. Oncogene, 14, 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prasad R., Dianov,G.L., Bohr,V.A. and Wilson,S.H. (2000) FEN1 stimulation of DNA polymerase β mediates an excision step in mammalian long patch base excision repair. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 4460–4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levin D.S., McKenna,A.E., Motycka,T.A., Matsumoto,Y. and Tomkinson,A.E. (2000) Interaction between PCNA and DNA ligase I is critical for joining of Okazaki fragments and long-patch base-excision repair. Curr. Biol., 10, 919–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Podlutsky A.J., Dianova,I.I., Podust,V.N., Bohr,V.A. and Dianov,G.L. (2001) Human DNA polymerase β initiates DNA synthesis during long-patch repair of reduced AP sites in DNA. EMBO J., 20, 1477–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sobol R.W., Horton,J.K., Kuhn,R., Gu,H., Singhal,R.K., Prasad,R., Rajewsky,K. and Wilson,S.H. (1996) Requirement of mammalian DNA polymerase-beta in base-excision repair. Nature, 379, 183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vispe S. and Satoh,M.S. (2000) DNA repair patch-mediated double strand DNA break formation in human cells. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 27386–27392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vispe S., Ho,E.L., Yung,T.M. and Satoh,M.S. (2003) Double-strand DNA break formation mediated by Flap endonuclease-1. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 35279–35285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bordone L. and Campbell,C. (2002) DNA ligase III is degraded by calpain during cell death induced by DNA-damaging agents. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 26673–26680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masson M., Niedergang,C., Schreiber,V., Muller,S., Menissier-de Murcia,J. and de Murcia,G. (1998) XRCC1 is specifically associated with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and negatively regulates its activity following DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 3563–3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whitehouse C.J., Taylor,R.M., Thistlethwaite,A., Zhang,H., Karimi-Busheri,F., Lasko,D.D., Weinfeld,M. and Caldecott,K.W. (2001) XRCC1 stimulates human polynucleotide kinase activity at damaged DNA termini and accelerates DNA single-strand break repair. Cell, 104, 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cleaver J.E. and Morgan,W.F. (1991) Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase: a perplexing participant in cellular responses to DNA breakage. Mutat. Res., 257, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu S.W., Wang,H., Poitras,M.F., Coombs,C., Bowers,W.J., Federoff,H.J., Poirier,G.G., Dawson,T.M. and Dawson,V.L. (2002) Mediation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cell death by apoptosis-inducing factor. Science, 297, 259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J., Tomkinson,A.E., Ramos,W., Mackey,Z.B., Danehower,S., Walter,C.A., Schultz,R.A., Besterman,J.M. and Husain,I. (1995) Mammalian DNA ligase III: molecular cloning, chromosomal localization and expression in spermatocytes undergoing meiotic recombination. Mol. Cell Biol., 15, 5412–5422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pippin J.W., Durvasula,R., Petermann,A., Hiromura,K., Couser,W.G. and Shankland,S.J. (2003) DNA damage is a novel response to sublytic complement C5b-9-induced injury in podocytes. J. Clin. Invest., 111, 877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hildeman D.A., Mitchell,T., Kappler,J. and Marrack,P. (2003) T cell apoptosis and reactive oxygen species. J. Clin. Invest., 111, 575–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nocentini S. (1999) Rejoining kinetics of DNA single- and double-strand breaks in normal and DNA ligase-deficient cells after exposure to ultraviolet C and gamma radiation: an evaluation of ligating activities involved in different DNA repair processes. Radiat. Res., 151, 423–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]