Abstract

Nesfatin-1 is an 82 amino acid peptide recently discovered in the brain which is derived from nucleobindin2 (NUCB2), a protein that is highly conserved across mammalian species. Nesfatin-1 has received much attention over the past two years due to its reproducible food intake-reducing effect that is linked with recruitment of other hypothalamic peptides regulating feeding behavior. A growing amount of evidence also supports that various stressors activate fore- and hindbrain NUCB2/nesfatin-1 circuitries. In this review, we outline the central nervous system distribution of NUCB2/nesfatin-1, and recent developments on the peripheral expression of NUCB2/nesfatin-1, in particular its co-localization with ghrelin in gastric X/A-like cells and insulin in β-cells of the endocrine pancreas. Functional studies related to the characteristics of nesfatin-1’s inhibitory effects on dark phase food intake are detailed as well as the central activation of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunopositive neurons in the response to psychological, immune and visceral stressors. Lastly, potential clinical implications of targeting NUCB2/nesfatin-1 signaling and existing gaps in knowledge to ascertain the role and mechanisms of action of nesfatin-1 are presented.

Keywords: body weight, brain - gut, food intake, gastric emptying, NUCB2/nesfatin-1, obesity, stress

Nesfatin-1 was discovered in 2006 by Oh-I and colleagues as an 82 amino acid (aa) polypeptide derived from the calcium and DNA-binding protein, nucleobindin2 (NUCB2) [1]. Besides nesfatin-1, putative post-translational processing of NUCB2 by the enzyme pro-hormone convertase (PC)-1/3 yields nesfatin-2 (aa residues 85 – 163) and nesfatin-3 (aa residues 166 – 396) [1], although no biological action has been reported for those peptides so far. Due to its inhibitory effect on food intake, the first cleavage product of NUCB2 was named nesfatin-1, an acronym for NUCB2-encoded satiety and fat influencing protein [1].

1. Central and Peripheral Expression of NUCB2/Nesfatin-1

1.1. Expression in the Brain

NUCB2 mRNA expression was initially detected in rat hypothalamic and brainstem nuclei implicated in the regulation of food intake, namely the arcuate nucleus, paraventricular nucleus (PVN), supraoptic nucleus, lateral hypothalamic area, zona incerta and the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) [1]. This expression pattern was similar to that of the protein as assessed by immunohistochemistry for NUCB2 and nesfatin-1 [1]. Subsequent studies extended these observations by detecting NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity in additional hypothalamic and hindbrain nuclei such as the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus, tuberal hypothalamic area, periventricular nucleus, arcuate nucleus, Edinger-Westphal nucleus, locus coeruleus, the medullary raphe nuclei and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, [2–7]. Lastly, we recently completed the central nervous system mapping of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 with additional forebrain and hindbrain nuclei including the insular cortex, central amygdaloid nucleus, ventrolateral medulla and cerebellum as well as preganglionic sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons of the thoracic, lumbar and sacral spinal cord in rats [7]. As also noticed by others [2, 3], we found that NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity was present only in the cytoplasm of cell bodies and proximal processes but not in varicosities and axon terminals [7], suggesting an action of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 as an intracellular modulator. However, cell bodies can also release cellular contents [8, 9] raising the possibility that nesfatin-1 may still act as an extracellular regulatory peptide.

The neurochemical content of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 positive cells has been extensively characterized. A large sub-population of hypothalamic NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactive neurons also expresses immunoreactivity for melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH, ~80% of MCH neurons co-label with NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity), cocaine-and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART, ~70%), α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH, ~60%), pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC, ~60–80%), vasopressin (~50%), oxytocin (~40%), growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH, ~30%), corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF, ~20%), thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH, ~20%), somatostatin or neurotensin (~10%) [2–5, 10]. Of interest, a recent study showed that hypothalamic arcuate neuropeptide Y (NPY)-containing neurons co-labeled with NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity (~40%) [6]. Moreover, NPY positive fibers were identified in the vicinity of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactive neurons [2]. In the brainstem, NUCB2/nesfatin-1 co-localizes with cholinergic and urocortin positive neurons of the Edinger-Westphal nucleus (~90%) [2, 11] and serotonin (5-HT)-containing neurons of the raphe medulla [2].

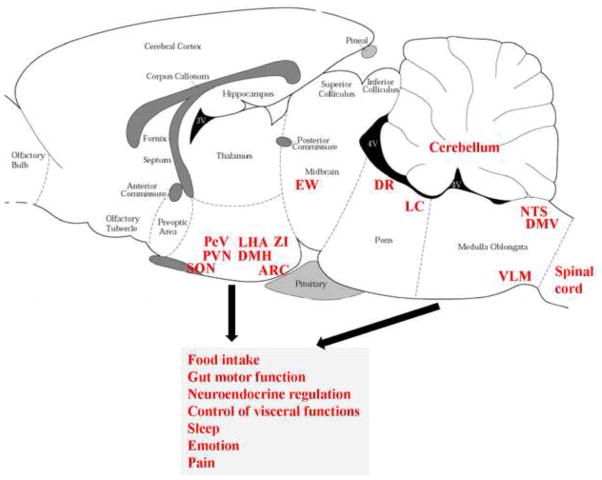

Collectively, existing evidence established a broad distribution of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity in discrete limbic, hypothalamic, pontine and medullary nuclei co-localized with a number of hypothalamic peptidergic integratory signals regulating food intake and other functions. These neuroanatomical studies greatly widened the knowledge of NUCB2/nesfatin-1’s distribution and point towards a broader role for NUCB2/nesfatin-1 that may encompass, in addition to feeding behavior, neuroendocrine regulation, autonomic control of visceral functions, sleep, emotion and pain (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Expression of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity in specific brain nuclei in rats and potential implication in various biological actions. Expression of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity in the central amygdaloid nucleus and insular cortex are not shown due to the sagittal level displayed here. 3v, third ventricle; 4v, fourth ventricle; ARC, arcuate nucleus; DMH, dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus; DMV, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve; DR, dorsal raphe nucleus; EW, Edinger-Westphal nucleus; LC, locus coeruleus; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; PeV, periventricular nucleus; SON, supraoptic nucleus; VLM, ventrolateral medulla; ZI, zona incerta.

1.2. Expression in Peripheral Tissues

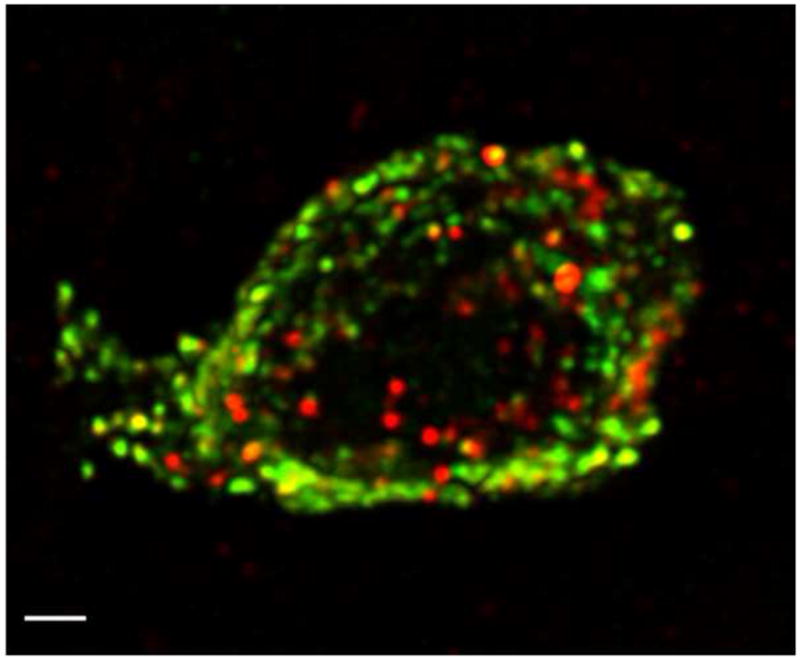

The brain and the gut overlap in their peptidergic content [12] and recent studies indicate that nesfatin-1 can cross the blood-brain barrier in both directions in a non-saturable manner [13, 14]. Thus, we investigated whether there is a peripheral source of nesfatin-1 and identified NUCB2 mRNA in the rat stomach [15]. Expression levels were 20-fold higher in the gastric oxyntic mucosa than those in the brain and 12-fold compared to other viscera such as the heart [15] as assessed by microarray analysis and confirmed by RT-qPCR. Immunostaining in peripheral tissues substantiated the expression of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in the rat stomach and additionally in the endocrine pancreas, pituitary gland and testis [15]. In the rat stomach, NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunosignals are mainly localized in mucosal endocrine X/A-like cells within a distinct sub-population of vesicles different from those containing the orexigenic hormone ghrelin (Fig. 2) [15], suggesting differential regulation and release of ghrelin and nesfatin-1. In the rodent and human endocrine pancreas, NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunostaining is restricted to insulin positive β-cells with a sub-cellular cytoplasmic localization distinct from that of insulin [16, 17]. Collectively, these data provide support at the cellular level for an exclusive endocrine cell distribution of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in the pituitary, stomach and pancreas which may impact on the regulation of hormone secretion, food intake and glycemic control in concert with ghrelin and insulin respectively.

Fig. 2.

High-resolution confocal microscopy of a single gastric cell co-expressing ghrelin (green) and NUCB2/nesfatin-1 (red) in separate cytoplasmic vesicles within the same cell. Confocal microscopy was performed using an x 100 objective and digital zoom, eight images in z-axis (stack size 24 × 24 × 7 μm) with dual laser excitation at 488 and 543 nm. Images were collected in two optical channels and photomultiplier tubes using FITC and TRITC filter sets, de-convoluted, and reconstructed into a three-dimensional image. Scale bar represents 1 μm. Reproduced with permission from reference [15]; Copyright 2009, The Endocrine Society.

1.3. Gaps to Fill

An important debate remains regarding the question whether NUCB2/nesfatin-1 are secreted neuroendocrine transmitters. Although post-translational cleavage of NUCB2 to nesfatin-1 is suggested by the presence of PC1/3, an enzyme involved in the processing of NUCB2 in central as well as peripheral tissues containing NUCB2 [1, 18], to date mature nesfatin-1 (1–82 aa) has only been reported in the cerebrospinal fluid of rats by Oh-I and colleagues in their initial study [1], whereas it was not present in hypothalamic protein extracts [1, 3]. Subsequent reports did not distinguish between nesfatin-1 and NUCB2 since the antibody, although raised against the full length nesfatin-1, also recognizes NUCB2 [7, 15, 16]. Moreover, we and others were unable to demonstrate endogenous mature nesfatin-1 (9.7 kDa) in the stomach, pancreas or plasma [15, 16]. One possible explanation is that the conditions used were not sensitive enough to detect nesfatin-1. However, when synthetic nesfatin-1 peptide (50 ng) was exogenously added, the peptide was identified on the Western Blot [15]. As NUCB2 displays biological activity upon third ventricular injection [1], this raises the possibility that the full length NUCB2 may be the biologically active compound that is released. Alternatively, since the structure of NUCB2 contains several motifs involved in intracellular signaling, namely a Ca2+-binding EF hand motif and a nuclear-binding basic helix-loop-helix sequence [19], NUCB2 may have a primarily intracellular role as recently suggested [17].

2. Inhibition of Food Intake, Body Weight and Digestive Functions by Nesfatin-1

2.1. Nesfatin-1 Injected into the Brain Inhibits Food Intake: Mechanisms of Action

In pioneered studies performed in rats, Oh-I and colleagues observed a reduction of dark phase food intake following third ventricular (3v) injection of nesfatin-1 at picomolar doses, whereas nesfatin-2 and nesfatin-3 had no effect [1]. Moreover, continuous infusion of nesfatin-1 into the 3v reduced food intake and body weight gain [1]. Likewise, when injected into the 3v of chronically cannulated mice, nesfatin-1 (1μg/mouse) induced a long-lasting decrease of dark phase food intake [10]. Consistent with the initial report, we found that nesfatin-1 injected into the lateral brain ventricle (intracerebroventricular, icv) at a low dose (0.05 μg/rat = 5 pmol/rat) induced a prolonged reduction of the dark phase food intake with a 3h delay in ad libitum fed rats [20]. These findings were confirmed under similar conditions of icv injection in freely fed rats by an independent group [21], who in addition reported that in overnight fasted rats, nesfatin-1 injected icv at a higher dose (180 pmol) induced a long-lasting reduction of water and food intake after a 3h delayed onset [21]. We also showed in rats that hindbrain injection of nesfatin-1 either at the level of the fourth ventricle (4v) or cisterna magna (ic) resulted in a rapid onset reduction of dark phase food intake which was also long-lasting [20]. The differential kinetics of the anorexigenic effect after icv and 4v/cisterna magna injection are indicative of distinct forebrain and hindbrain sites of action for nesfatin-1. In the forebrain, the PVN has been localized as an effector site for the nesfatin-1-induced suppression of dark phase food intake [10]. Collectively, these data provide consistent evidence attesting the potency of nesfatin-1 when injected into the lateral [20, 21], 3rd [1, 10], or 4th brain ventricle [20], cisterna magna [20], or PVN [10] to induce a sustained suppression of the dark phase feeding in ad libitum fed rats, and in mice when injected into the 3v [10].

Neural mechanisms involved in nesfatin-1’s anorexigenic effect encompass the recruitment of several hypothalamic and medullary anorexigenic pathways [1, 10, 20, 21]. Since the kinetics of food intake reduction upon icv injection resembled the anorexigenic action of the CRF2 receptor agonists, urocortins [22, 23], we investigated the potential role of brain CRF2 receptors. We found that the icv nesfatin-1-induced reduction of dark phase feeding is CRF2-dependent as shown by the complete blockade of nesfatin-1’s anorexigenic effect by pretreatment with the CRF2 antagonist, astressin2-B injected icv [20]. However, the CRF2 antagonist did not alter the rapid onset food intake suppression following ic nesfatin-1 [20], further supporting differential forebrain and hindbrain sites and mechanisms of nesfatin-1’s anorexic action. Other studies established that nesfatin-1’s action is mediated by a leptin-independent activation of the melanocortin system. Initial reports showed that 3v injection of nesfatin-1 results in a similar reduction of dark phase food intake in leptin receptor-deficient Zucker rats and control rats [1]. By contrast, the melanocortin 3/4 receptor antagonist, SHU9119 injected into the 3v abrogated and into the lateral ventricle attenuated the anorexigenic effect of nesfatin-1 injected by the same route in rats [1, 21]. Recently, Maejima et al. used combined approaches to delineate a hypothalamic nesfatin-1/oxytocin - medullary melanocortin pathway by showing that nesfatin-1 injected into the 3v activates oxytocinergic PVN neurons projecting to the NTS resulting in the activation of NTS POMC neurons and related melanocortin 3/4 receptors leading to a melanocortin-dependent and leptin-independent anorexigenic action [10]. In line with these findings, an oxytocin antagonist injected into the lateral cerebroventricle blocks the inhibitory effects of icv nesfatin-1 on food intake [24]. Likewise, the oxytocin antagonist icv also prevents the α-MSH induced reduction of food intake indicating an action for oxytocin downstream of the melanocortin system [24]. Additional mechanisms of nesfatin-1’s action may involve a direct inhibitory effect on the activity of neurons in the arcuate nucleus containing the orexigenic peptide, NPY as suggested by the electrophysiological demonstration that nesfatin-1 hyperpolarizes NPY positive arcuate neurons in vitro [25].

A number of peptides acting in the brain to influence food intake also regulate digestive functions which may also impact on satiety signaling [12]. We recently reported that nesfatin-1 injected icv at a dose effective to suppress food intake, dose-dependently suppresses gastric emptying in fasted rats. However, this effect was independent from the activation of CRF2 signaling [20] indicative of different mechanisms involved in the suppression of gastric transit and food intake. The underlying mechanisms of delayed gastric emptying induced by central nesfatin-1 are still to be characterized.

2.2. Physiological Role of Brain NUCB2/Nesfatin-1 in Food Intake Regulation

Initial studies by Oh-I et al. showed that 3rd ventricular injection of a NUCB2 antisense oligonucleotide (40μg/d for 10 days) increased food intake and body weight gain suggesting a physiological function of hypothalamic NUCB2/nesfatin-1 as an anorexigenic modulator of food intake [1]. A physiological role of central NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in food intake regulation is further supported by changes in the expression of NUCB2 depending upon the metabolic status of the animals. Fasting for 24h decreased NUCB2 mRNA expression selectively in the PVN which translated into reduced NUCB2 protein content in this nucleus [1]. Likewise, fasting decreased NUCB2 mRNA expression in the supraoptic nucleus, which was recently implicated in the regulation of food intake [26], whereas re-feeding restored basal levels [5]. Conversely, re-feeding after a 24h fast activated NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactive neurons in the supraoptic nucleus as assessed by Fos immunoreactivity [20]. In addition, consistent with the assumption that hypothalamic NUCB2/nesfatin-1 is acting as an anorexigenic regulator of food intake, the administration of anorexigenic substances such as α-MSH or the serotonin 5-HT1B/2C receptor agonist, m-chlorophenylpiperazine increases the expression of hypothalamic NUCB2 in rodents [1, 27]. We also previously reported that peripheral injection of desacyl ghrelin at a dose preventing the orexigenic action of ghrelin activates NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactive neurons of the arcuate nucleus [28], which are mainly co-localized with POMC/CART [2, 6]. Moreover, the satiety peptide, cholecystokinin (CCK) injected peripherally in rats activates NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunopositive cells in the PVN and NTS [20, 29] suggesting a role in the mediation of gut peptide satiety signaling.

2.3. Nesfatin-1 Injected Peripherally Suppresses Food Intake: Mechanism of Action

The actions of nesfatin-1 injected peripherally have been less well explored than its central effects. Existing functional studies demonstrated a reduction of dark phase food intake upon intraperitoneal nesfatin-1 in ad libitum fed mice when injected 30 min before onset of the dark photoperiod [30]. However, the dose at which the response occurs is >1000-fold higher than that required when injected into the brain. The inhibitory effect was retained under leptin resistant conditions such as high fat diet-induced obesity or in db/db mice bearing a mutation in the leptin receptor gene [30] pointing towards a leptin-independent action as observed upon brain injection [1]. The structure activity relationship using different N- (1–23 aa) or C- (54–82 aa) terminal, or middle (24–53 aa) nesfatin-1 fragments showed that the biological activity to suppress dark phase food intake is retained in the middle fragment, whereas ip injection of the N- and C-terminal fragments had no effect [30]. The anorexigenic effect of nesfatin-124–53 injected ip was abolished in mice pre-treated with capsaicin [31] indicating a potential vagally-mediated pathway between peripheral nesfatin-1 and the brain. In line with these findings, nesfatin-1 activates neurons in the nodose ganglion in vitro [32]. These data, along with mapping of medullary Fos positive neurons in response to intraperitoneal injection of nesfatin-1, support the assumption that peripheral nesfatin-1 can influence the activity of vagal afferents and possibly suppress feeding by activating POMC and CART neurons in the NTS [31]. Therefore, data so far support a peripheral nesfatin-1 signaling pathway that may involve the vagus nerve consistent with the prominent expression of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in the stomach and the vagal mediation commonly established for other gut satiety peptides [33].

The potential relevance of peripheral NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in food intake regulation is supported by the demonstration that fasting decreased NUCB2 mRNA expression in an enriched population of gastric endocrine cells as assessed by microarray analysis and substantiated by RT-qPCR [15]. This decrease translates in a reduction of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 plasma levels that are restored after re-feeding [20]. Other studies in Wistar and Goto-Kakizaki rats with type 2 diabetes indicate that plasma NUCB2 levels follow an inverse relationship with plasma glucose [17] indicative of a dynamic relationship with the glycemic state.

2.4. Gaps to Fill

In contrast to the increasing amount of literature on the biological actions of administered nesfatin-1 and expression of endogenous NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in tissues, still nothing is known about the receptor(s) mediating those effects. Their characterization, localization in the brain as well as periphery, e.g. in the stomach, pancreas and on vagal afferents, along with their regulation will be key components required for the understanding of the NUCB2/nesfatin-1 signaling system. So far, one study showing that nesfatin-1 elevates Ca2+ flux linked with protein kinase A in cultured rat hypothalamic neurons has been indicative of a G-protein coupled receptor [2]. With regards to the understanding of nesfatin-1 brain sites of action, additional microinjection studies will be necessary to define specific nuclei, in addition to the PVN, responsive to nesfatin-1, particularly at the level of the hindbrain to get insight into the differential effects on food intake and digestive functions [20]. Of interest is the fact that all studies so far consistently indicated a reduction of dark phase food intake following nesfatin-1 injected centrally [1, 10, 20, 21] or peripherally [30], whereas there are fewer studies and less consistent effects during the light phase in fasted rats [20, 21]. Underlying mechanisms such as clock gene dependency or interaction with other neuropeptides specifically recruited during the dark photoperiod of physiological food ingestion remain to be investigated. In addition to the reduction of dark phase food intake, there is preliminary evidence that a single icv injection of nesfatin-1, although not modulating the 24h cumulative food intake, reduced body weight as assessed 24h post injection [20]. These data suggest a central action of nesfatin-1 to increase energy expenditure which also warrants further investigation. Lastly, the recently established crosstalk between nesfatin-1 and CRF, oxytocin and melanocortin pathways involved in hypothalamic nesfatin-1’s anorexigenic action are still to be further clarified.

3. Brain Activation of NUCB2/Nesfatin-1 Immunoreactive Neurons by Stressors

Based on the finding that icv nesfatin-1 exerts a CRF receptor-dependent effect on food intake [20] and the central distribution in forebrain, hindbrain and spinal autonomic nuclei [7], along with the expression of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in CRF neurons [3], we hypothesized a role for nefatin-1 in the response to stress. In line with this assumption, a previous report indicated that nesfatin-1 injected icv increases anxiety and fear as assessed by reduced time spent in the open arms during the elevated plus maze test and increased startle response and freezing in an emotional response test [34]. However, these behavioral changes were observed in response to nesfatin-1 injected at higher doses than those inducing a reduction of food intake [34]. Restraint is considered as emotional stressor [35] which is processed and integrated by the brain, especially cortical limbic and pontine areas as well as hypothalamic nuclei [36]. Restraint was reported to activate NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactive neurons in distinct hypothalamic and hindbrain nuclei as assessed by double immunohistochemistry (Table 1) [11, 37] supporting a role for nesfatin-1 in the response to stress. Similarly, an immunological stressor, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), injected intraperitoneally activated NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunopositive neurons in hypothalamic and hindbrain nuclei (Table 1) [38] pointing towards a role of nesfatin-1 in the mediation of the anorexigenic response observed under conditions of inflammation. Since we observed a dose-dependent delay of gastric emptying following icv nesfatin-1, we used abdominal surgery that is well established to induce postoperative gastric ileus and activate hypothalamic and medullary neurons regulating digestive function [39, 40] as a model to assess whether central NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactive neurons are part of the circuitry activated under these conditions. Abdominal surgery consisting of laparotomy and cecal palpation activated NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunopositive neurons in the magnocellular neuroendocrine system, in the anterior parvicellular part of the PVN, Edinger-Westphal nucleus and nuclei of the catecholaminergic and serotonergic system as assessed by double immunostaining for Fos and NUCB2/nesfatin-1 (Table 1) [41]. Taken together, these data suggest that psychological, immune and visceral stressors recruit key brain neuronal circuitries containing NUCB2/nesfatin-1 involved in the behavioral, endocrine and autonomic responses to stress.

Table 1.

Activation of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 immunoreactive neurons in the brain induced by psychological, immune and visceral stressors in rats as assessed by Fos immunohistochemistry.

| Brain nucleus | Percentage of activated neurons immunopositive for NUCB2/nesfatin-1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Restraint | Lipopolysaccharide ip | Abdominal surgery | |

| Supraoptic nucleus | 95 | 52 | 99 |

| Anterior parvicellular PVN | 48 | 34 (whole PVN) | 71 |

| Lateral magnocellular PVN | 18 | ni | 47 |

| Medial magnocellular PVN | 27 | ni | 41 |

| Medial parvicellular PVN | 10 | ni | 9 |

| Arcuate nucleus | nd | 5 | nd |

| Locus coeruleus | 80 | ni | 91 |

| Rostral raphe pallidus | 57 | ni | 82 |

| Edinger-Westphal nucleus | nd | ni | 74 |

| Ventrolateral medulla | 90 | ni | 74 |

| Nucleus of the solitary tract | 48 (caudal part) | 20 | 14 |

4. Clinical Implications

Leptin resistance is commonly observed in most of the obese individuals, therefore precluding to target leptin pathways [42]. Since convergent evidence indicates a leptin-independent action of nesfatin-1 to reduce food intake [1, 30], nesfatin-1 may be a potential target in the drug treatment of obesity and associated diseases. In line with this notion, preliminary pre-clinical data suggesting possible efficacy of subcutaneous and intranasal routes of administration of nesfatin-1 in mice and rats as indicated by long lasting reduction of food intake are promising [43], although this needs further confirmation.

Besides potential use in the drug treatment of diseases, nesfatin-1 may be informative as a biomarker. A recent report indicated that patients with newly diagnosed primary generalized epilepsy have significant 129- and 167-fold higher circulating and saliva NUCB2/nesfatin-1 levels respectively which were normalized under treatment [44]. These findings suggest the possible relevance of nesfatin-1 as a biomarker not only in the diagnosis but also in the monitoring of responsiveness to treatment for patients with epilepsy. This and a possible causative association of epilepsy and NUCB2/nesfatin-1 warrant further investigations.

5. Summary

The existing experimental data reported so far support a role for nesfatin-1 to curtail nocturnal food intake in rodents. This is based on functional studies showing the potent anorexigenic action of nesfatin-1 when injected into the brain at low picomolar doses during the dark phase and its prolonged duration of action along with the neuroanatomical distribution of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in specific hypothalamic and hindbrain nuclei co-localized with other peptides regulating food intake and inverse modulation of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 by feeding and fasting. Moreover, consistent with peptidergic brain-gut interactions, recent evidence established high expression of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in endocrine cells of the stomach (X/A-like cells co-expressing ghrelin) and pancreas (β-cells co-expressing insulin), the regulation of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in the stomach and blood under different metabolic conditions, and a potential vagal-dependent satiety action of peripherally injected nesfatin-1. Of significance in relation with the broad distribution of NUCB2/nesfatin-1 in specific brain nuclei known to respond to various stressors, several reports established the recruitment of the central NUCB2/nesfatin-1 signaling system in the response to psychological, immune or visceral stressors, including the hypothalamus, locus coeruleus and NTS. Whether nesfatin-1 will have clinical implications in the drug treatment of obesity is still early to be ascertained, however, its potency and leptin-independent mechanism of action are relevant features. A recent report points to nesfatin-1 as a biomarker in diseases such as epilepsy. However, an important missing link is the knowledge of the nesfatin-1 receptor, as its characterization will represent a leap forward in the understanding of the mediation of nesfatin-1’s effects. Another key issue relates to establish whether mature nesfatin-1 is expressed in brain tissues or gut endocrine cells.

Acknowledgments

Supported by German Research Foundation Grants STE 1765/1-1 (A.S.), VA Research Scientist Award, NIHDK 33061, Center Grant DK-41301 (Animal Core) (Y.T.)

We thank Ms. Eugenia Hu for reviewing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 3v

third ventricle

- 4v

fourth ventricle

- 5-HT

serotonin

- α-MSH

α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone

- aa

amino acid

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CART

cocaine-and amphetamine-regulated transcript

- CRF

corticotropin-releasing factor

- EW

Edinger-Westphal nucleus

- GHRH

growth hormone-releasing hormone

- ic

intracisternal

- icv

intracerebroventricular

- ip

intraperitoneal

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MCH

melanin-concentrating hormone

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- NTS

nucleus of the solitary tract

- PC

pro-hormone convertase

- POMC

pro-opiomelanocortin

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus

- TRH

thyrotropin-releasing hormone

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: A.S. and Y.T. have nothing to disclose. No conflicts of interest exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Oh-I S, Shimizu H, Satoh T, Okada S, Adachi S, Inoue K, Eguchi H, Yamamoto M, Imaki T, Hashimoto K, Tsuchiya T, Monden T, Horiguchi K, Yamada M, Mori M. Identification of nesfatin-1 as a satiety molecule in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2006;443:709–12. doi: 10.1038/nature05162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brailoiu GC, Dun SL, Brailoiu E, Inan S, Yang J, Chang JK, Dun NJ. Nesfatin-1: distribution and interaction with a G protein-coupled receptor in the rat brain. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5088–94. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foo K, Brismar H, Broberger C. Distribution and neuropeptide coexistence of nucleobindin-2 mRNA/nesfatin-like immunoreactivity in the rat CNS. Neuroscience. 2008;156:563–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fort P, Salvert D, Hanriot L, Jego S, Shimizu H, Hashimoto K, Mori M, Luppi PH. The satiety molecule nesfatin-1 is co-expressed with melanin concentrating hormone in tuberal hypothalamic neurons of the rat. Neuroscience. 2008;155:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohno D, Nakata M, Maejima Y, Shimizu H, Sedbazar U, Yoshida N, Dezaki K, Onaka T, Mori M, Yada T. Nesfatin-1 neurons in paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the rat hypothalamus coexpress oxytocin and vasopressin and are activated by refeeding. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1295–301. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inhoff T, Stengel A, Peter L, Goebel M, Taché Y, Bannert N, Wiedenmann B, Klapp BF, Mönnikes H, Kobelt P. Novel insight in distribution of nesfatin-1 and phospho-mTOR in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus of rats. Peptides. 2010;31:257–62. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goebel M, Stengel A, Wang L, Lambrecht NWG, Taché Y. Nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity in rat brain and spinal cord autonomic nuclei. Neurosci Lett. 2009;452:241–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bustos G, Abarca J, Campusano J, Bustos V, Noriega V, Aliaga E. Functional interactions between somatodendritic dopamine release, glutamate receptors and brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in mesencephalic structures of the brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;47:126–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landgraf R, Neumann ID. Vasopressin and oxytocin release within the brain: a dynamic concept of multiple and variable modes of neuropeptide communication. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2004;25:150–76. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maejima Y, Sedbazar U, Suyama S, Kohno D, Onaka T, Takano E, Yoshida N, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Fujiwara K, Yashiro T, Horvath TL, Dietrich MO, Tanaka S, Dezaki K, Oh IS, Hashimoto K, Shimizu H, Nakata M, Mori M, Yada T. Nesfatin-1-regulated oxytocinergic signaling in the paraventricular nucleus causes anorexia through a leptin-independent melanocortin pathway. Cell Metab. 2009;10:355–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okere B, Xu L, Roubos EW, Sonetti D, Kozicz T. Restraint stress alters the secretory activity of neurons co-expressing urocortin-1, cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript peptide and nesfatin-1 in the mouse Edinger-Westphal nucleus. Brain Res. 2010;1317C:92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardiner JV, Jayasena CN, Bloom SR. Gut hormones: a weight off your mind. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:834–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan W, Hsuchou H, Kastin AJ. Nesfatin-1 crosses the blood-brain barrier without saturation. Peptides. 2007;28:2223–8. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price TO, Samson WK, Niehoff ML, Banks WA. Permeability of the blood-brain barrier to a novel satiety molecule nesfatin-1. Peptides. 2007;28:2372–81. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stengel A, Goebel M, Yakubov I, Wang L, Witcher D, Coskun T, Taché Y, Sachs G, Lambrecht NW. Identification and characterization of nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity in endocrine cell types of the rat gastric oxyntic mucosa. Endocrinology. 2009;150:232–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez R, Tiwari A, Unniappan S. Pancreatic beta cells colocalize insulin and pronesfatin immunoreactivity in rodents. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381:643–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foo KS, Brauner H, Ostenson CG, Broberger C. Nucleobindin-2/nesfatin in the endocrine pancreas: distribution and relationship to glycaemic state. J Endocrinol. 2010;204:255–63. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee YC, Damholt AB, Billestrup N, Kisbye T, Galante P, Michelsen B, Kofod H, Nielsen JH. Developmental expression of proprotein convertase 1/3 in the rat. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;155:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin P, Fischer T, Weiss T, Farquhar MG. Calnuc, an EF-hand Ca(2+) binding protein, specifically interacts with the C-terminal alpha5-helix of G(alpha)i3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:674–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stengel A, Goebel M, Wang L, Rivier J, Kobelt P, Mönnikes H, Lambrecht NW, Taché Y. Central nesfatin-1 reduces dark-phase food intake and gastric emptying in rats: differential role of corticotropin-releasing factor2 receptor. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4911–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yosten GL, Samson WK. Nesfatin-1 exerts cardiovascular actions in brain: possible interaction with the central melanocortin system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R330–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90867.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zorrilla EP, Taché Y, Koob GF. Nibbling at CRF receptor control of feeding and gastrocolonic motility. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:421–7. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fekete EM, Inoue K, Zhao Y, Rivier JE, Vale WW, Szucs A, Koob GF, Zorrilla EP. Delayed satiety-like actions and altered feeding microstructure by a selective type 2 corticotropin-releasing factor agonist in rats: intra-hypothalamic urocortin 3 administration reduces food intake by prolonging the post-meal interval. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1052–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yosten GL, Samson WK. The anorexigenic and hypertensive effects of nesfatin-1 are reversed by pretreatment with an oxytocin receptor antagonist. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00804.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price CJ, Samson WK, Ferguson AV. Nesfatin-1 inhibits NPY neurons in the arcuate nucleus. Brain Res. 2008;1230:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnstone LE, Fong TM, Leng G. Neuronal activation in the hypothalamus and brainstem during feeding in rats. Cell Metab. 2006;4:313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nonogaki K, Ohba Y, Sumii M, Oka Y. Serotonin systems upregulate the expression of hypothalamic NUCB2 via 5-HT2C receptors and induce anorexia via a leptin-independent pathway in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:186–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inhoff T, Mönnikes H, Noetzel S, Stengel A, Goebel M, Dinh QT, Riedl A, Bannert N, Wisser AS, Wiedenmann B, Klapp BF, Taché Y, Kobelt P. Desacyl ghrelin inhibits the orexigenic effect of peripherally injected ghrelin in rats. Peptides. 2008;29:2159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noetzel S, Stengel A, Inhoff T, Goebel M, Wisser AS, Bannert N, Wiedenmann B, Klapp BF, Taché Y, Mönnikes H, Kobelt P. CCK-8S activates c-Fos in a dose-dependent manner in nesfatin-1 immunoreactive neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the brainstem. Regul Pept. 2009;157:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu H, Oh-I S, Hashimoto K, Nakata M, Yamamoto S, Yoshida N, Eguchi H, Kato I, Inoue K, Satoh T, Okada S, Yamada M, Yada T, Mori M. Peripheral Administration of Nesfatin-1 Reduces Food Intake in Mice: The leptin-independent mechanism. Endocrinology. 2009;150:662–71. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu H, Ohsaki A, Oh IS, Okada S, Mori M. A new anorexigenic protein, nesfatin-1. Peptides. 2009;30:995–8. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwasaki Y, Nakabayashi H, Kakei M, Shimizu H, Mori M, Yada T. Nesfatin-1 evokes Ca2+ signaling in isolated vagal afferent neurons via Ca2+ influx through N-type channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:958–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stengel A, Taché Y. The physiological relationships between the brainstem, vagal stimulation and feeding. In: Preedy VR, editor. The International Handbook of Behavior, Diet and Nutrition. London: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merali Z, Cayer C, Kent P, Anisman H. Nesfatin-1 increases anxiety- and fear-related behaviors in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;201:115–23. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dayas CV, Buller KM, Day TA. Neuroendocrine responses to an emotional stressor: evidence for involvement of the medial but not the central amygdala. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2312–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dayas CV, Buller KM, Day TA. Medullary neurones regulate hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor cell responses to an emotional stressor. Neuroscience. 2001;105:707–19. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goebel M, Stengel A, Wang L, Taché Y. Restraint stress activates nesfatin-1-immunoreactive brain nuclei in rats. Brain Res. 2009;1300:114–24. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonnet MS, Pecchi E, Trouslard J, Jean A, Dallaporta M, Troadec JD. Central nesfatin-1 expressing neurons are sensitive to peripheral inflammatory stimulus. J Neuroinflammation. 2009;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barquist E, Bonaz B, Martinez V, Rivier J, Zinner MJ, Taché Y. Neuronal pathways involved in abdominal surgery-induced gastric ileus in rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R888–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.4.R888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonaz B, Plourde V, Taché Y. Abdominal surgery induces Fos immunoreactivity in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1994;349:212–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stengel A, Goebel M, Wang L, Taché Y. Abdominal surgery activates nesfatin-1 immunoreactive brain nuclei in rats. Peptides. 2010;31:263–70. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myers MG, Cowley MA, Munzberg H. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:537–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu H, Oh IS, Okada S, Mori M. Nesfatin-1: An Overview and Future Clinical Application. Endocr J. 2009;56:527–43. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k09e-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aydin S, Dag E, Ozkan Y, Erman F, Dagli AF, Kilic N, Sahin I, Karatas F, Yoldas T, Barim AO, Kendir Y. Nesfatin-1 and ghrelin levels in serum and saliva of epileptic patients: hormonal changes can have a major effect on seizure disorders. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;328:49–56. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]