Abstract

Krüppel-Like Factor 4 (KLF4) functions as a tumor suppressor in some cancers, but its molecular mechanism is not clear. Our recent study also showed that the expression of KLF4 is dramatically reduced in primary lung cancer tissues. To investigate the possible role of KLF4 in lung cancer, we stably transfected KLF4 into cells from lung cancer cell lines H322 and A549 to determine the cells’ invasion ability. Our results showed that ectopic expression of KLF4 extensively suppressed lung cancer cell invasion in Matrigel. This effect was independent of KLF4-mediated p21 up-regulation because ectopic expression of p21 had minimal effect on cell invasion. Our analysis of the expression of 12 genes associated with cell invasion in parental, vector-transfected, and KLF4-transfected cells showed that ectopic expression of KLF4 resulted in extensively repressed expression of secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), an extracellular matrix protein that plays a role in tumor development and metastasis. Knockdown of SPARC expression in H322 and A549 cells led to suppression of cell invasion, comparable to that observed in KLF4-transfected cells. Moreover, retrovirus-mediated restoration of SPARC expression in KLF4-transfected cells abrogated KLF4-induced anti-invasion activity. Together, our results indicate that KLF4 inhibits lung cancer cell invasion by suppressing SPARC gene expression.

Keywords: KLF4, tumor invasion, lung, carcinoma, SPARC

Introduction

Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC, also named osteonectin or BM40) is an extracellular matrix protein that binds selectively to collagen fibrils and minerals and plays an important role in bone calcification. 1 A growing body of evidence has shown that SPARC also plays a role in tumor development and metastasis. Overexpression of SPARC has been associated with the progression of, and poor outcome in, various cancers, including melanoma, 2 glioma, 3,4 and cancers of the breast, 5,6 prostate, 7 liver, 8 pancreas, 9 bladder, 10 head and neck, 11,12 and lung. 13 Molecular characterization has revealed that SPARC can suppress E-cadherin expression, induce mesenchymal transition, and promote tumor cell invasion and metastasis. 14–16 It can also promote cell survival by activating AKT, focal adhesion kinase, and/or integrin-linked kinase. 17,18 In addition, SPARC-derived peptides may play a role in angiogenesis. 19 Suppression of SPARC expression by a SPARC antisense expression vector suppressed in vitro adhesive and invasive capacities of melanoma cells and completely abolished their in vivo tumorigenicity. 20 These observations collectively indicated that SPARC plays a critical role in invasive/metastatic phenotype in various tumors. However, controversial results associated with both the overexpression and underexpression of SPARC have been reported in colorectal cancer. 21,22 SPARC has also been found to induce apoptosis in ovarian cancer 23 but to inhibit metastasis in some breast cancer cells. 24 Thus, the role of SPARC in tumor progression and invasion may be dependent on tissue type or cell context. Nevertheless, little is known about the regulation of SPARC expression in normal and tumor tissues.

As seen with SPARC, altered expression of Krüppel-Like Factor 4 (KLF4) has been reported in various cancers, and down-regulation of KLF4 has been associated with cancer development, progression, and metastasis. 25,26 KLF4, a SP1-like zinc finger transcriptional factor, 27 has been reported to play an important role in stem cells. 28 Our recent study showed that KLF4 may function as a tumor-suppressive gene in lung cancer because expression of KLF4 is down-regulated in a substantial number of primary lung cancers and because ectopic expression of KLF4 suppressed lung cancer cell proliferation and clonogenic formation in vitro. Moreover, enforced expression of KLF4 in lung cancer cells by ex vivo transfection or by adenovector-mediated gene transfer suppressed tumor growth in vivo. 29 However, the molecule mechanisms underlying KLF4’s tumor-suppressive function in lung cancer remain to be determined.

To further explore the possible role of KLF4 in lung cancer, we analyzed lung cancer cell invasion with or without ectopic expression of KLF4. Our results showed that ectopic expression of KLF4 extensively suppressed lung cancer invasion and that this anti-invasion effect was not caused by up-regulation of p21, a cell cycle regulator whose expression is regulated by KLF4, 30 because ectopic expression of p21 had no effect on lung cancer invasion. Analysis of several genes involved in cell invasion revealed that ectopic expression of KLF4 led to a drastic suppression of SPARC gene expression, suggesting that KLF4 suppresses lung cancer cell invasion by suppressing SPARC expression.

Results

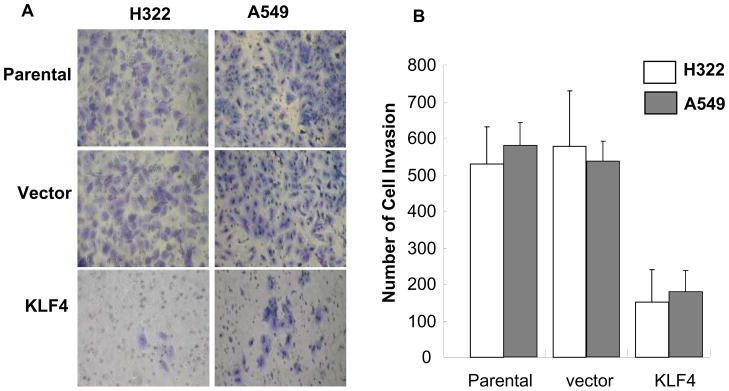

Enforced expression of KLF4-suppressed lung cell invasion

We recently found that ectopic expression of KLF4 resulted in marked inhibition of lung cancer cell growth and clonogenic formation and that knockdown of KLF4 promoted cell growth in immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells. 29 To further explore the biologic function of the KLF4 gene in lung cancer cells, we determined the extent of lung cancer cell invasion after retrovirus-mediated KLF4 gene transfer. H322 and A549 cells were infected with retrovirus expressing KLF4 or a control vector and selected with geneticin. The parental, KLF4-transfected, or control vector-transfected H322 and A549 cells were then analyzed for their ability to invade a Matrigel-coated membrane. The results showed that ectopic expression of KLF4 in H322 and A549 cells, compared with that of parental and control vector–transformed cells, significantly suppressed cell invasion (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1). This suppression of cell invasion is unlikely caused by KLF4-mediated cell growth inhibition because KLF4 stably transfected cells had similar growth rate as parental cells when tested at 24–72 h after cell seeding, although those cells had dramatically reduced clonogenic formation ability when compared with parental cells at a relatively long-term cell culture (9 days). This result indicated that KLF4 is critical in lung cancer cell invasion.

Fig. 1. Ectopic expression of KLF4 suppressed lung cancer cell invasion.

The cell-invasion assay was performed with use of Matrigel, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Parental, vector-transfected, and KLF4-transfected H322 and H549 cells were used in the study. (A) Representative areas of invaded cells. (B) Number of invaded cells/field in three transwells. Values represent mean + SD number of cells/field. The experiment was repeated at least twice with similar results.

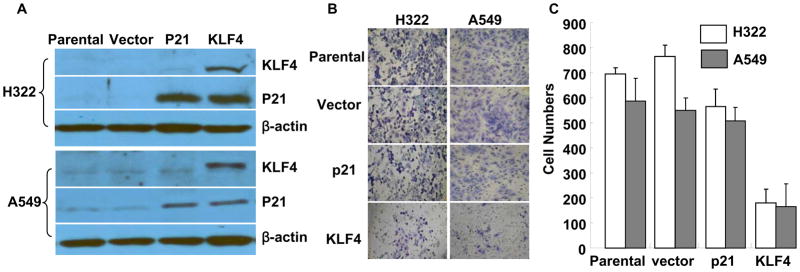

KLF4-mediated anti-invasion activity is independent of P21 up-regulation

KLF4 is known to activate p21(WAF1/Cip1) through a specific Sp1-like cis-element in the p21(WAF1/Cip1) proximal promoter. 31 Our recent studies also revealed that ectopic expression of KLF4 in lung cancer cells up-regulated p21 expression. 29 To test whether KLF4-mediated anti-invasion activity is associated with up-regulation of p21 and consequent cell cycle arrest at G1 phase, we established H322 and A549 cells stably overexpressing p21 and evaluated their in vitro invasion ability. Western blot analysis revealed that H322 and A549 cells transfected with KLF4 and p21 had equivalent levels of p21 expression (Fig. 2A). Nevertheless, an in vitro Matrigel cell-invasion assay showed that ectopic expression of p21 in H322 and A549 cells, compared with that in parental and empty vector–transfected cells, had no obvious effect on cell invasion (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2B, 2C). These results indicated that KLF4-mediated anti-invasion activity was not associated with the up-regulation of p21 expression in lung cancer.

Fig. 2. Effects of KLF4 and p21 expression on cancer cell invasion.

(A) Western blots of KLF4 and p21 expression in H322 and A549 cells transfected with either KLF4 or p21. Parental and vector-transfected cells were used as controls. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B), (C), Cell-invasion assay performed in cells listed in (A): (B) Representative areas of invaded cells. (C) Number of invaded cells/field in three transwells. Values represent mean + SD number of cells/field. The experiment was repeated at least twice with similar results.

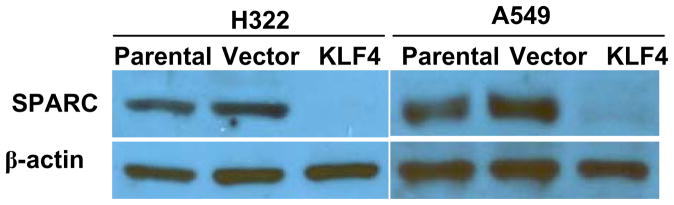

Ectopic expression of KLF4 leads to extensive down-regulation of SPARC

To further investigate the mechanisms underlying KLF4-induced anti-invasion activity, we analyzed the expression of various genes that were reported to play roles in cancer cell invasion, 32,33 including MMP1, MMP9, SPARC, TERT, PKLR, IL3RA, IGF1, VEGFA, RHOC, TGFB1, PLAU, and VCAM1 (28–34). For this purpose, we isolated total RNA and determined mRNA levels in these genes in parental, vector-transfected, and KLF4-transfected H322 and A549 cells by using real-time PCR. The housekeeping gene ACTB (also know as β-actin) was used as the internal reference gene to control mRNA quantity. As expected, cells transfected with KLF4 had higher levels of KLF4 mRNA than did parental or vector control cells. For most genes tested, ectopic expression of KLF4 did not lead to extensive changes at mRNA levels. Of interest, a substantial reduction in mRNA levels was observed for SPARC in both KLF4-transfected H322 and A549 cells, compared with levels in parental and vector-transfected cells (Table 1). This result was confirmed by protein analysis. SPARC expression was easily detectable in parental and vector-transfected cells but was completely abolished in KLF4-transfected cells (Fig. 3). These results indicated that expression of SPARC is regulated by KLF4 in lung cancer cells.

Table 1.

mRNA levels some invasion-related genes determined by real time PCR

| H322 | A549 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | Parental | Vector | KLF4 | Parental | Vector | KLF4 |

| KLF4 | 1.79 | 0.35 | 5.47 | 0.66 | 0.26 | 4.08 |

| SPARC | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.00 |

| MMP-1 | 0.76 | 0.34 | 0.5 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| MMP-9 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| TERT | 0.27 | 0.15 | 1.63 | 1.87 | 0.52 | 2.23 |

| PKLR | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.18 |

| IL3RA | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.43 | 0.23 | 0.58 |

| IGF1 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| VEGFA | 46.7 | 21.4 | 58.1 | 41.3 | 28.3 | 31.2 |

| RHOC | 19.6 | 8.45 | 25.5 | 28.9 | 20.1 | 36.6 |

| TGFB1 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 2.12 | 13.3 | 8.50 | 13.5 |

| PLAU | 54.6 | 58.1 | 26.6 | 22.3 | 14.8 | 7.26 |

| VCAM1 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.09 |

Fig. 3. Effects of KLF4 on SPARC protein expressions.

SPARC expression was determined by Western blot analysis on parental, vector-transfected, and KLF4-transfected H322 and A549 cells. Enforced expression of KLF4 in H322 and A549 led t0 extensive down-regulation of SPARC expression. β-actin was used as a loading control.

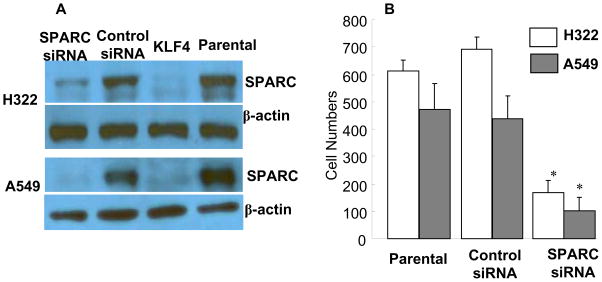

Knockdown of SPARC inhibited cell invasion in vitro

SPARC, also known as osteonectin, is an extracellular matrix protein that plays an important role in the calcification of bone (1) It is reported to promote cancer cell invasion and migration in glioma and prostate cancer. 4,34 SPARC overexpression is often associated with the most aggressive and highly metastatic tumors. 35 To investigate whether down-regulation of SPARC alters cell invasion activity in human lung cancer, we inhibited SPARC expression in H322 and A549 cells by using SPARC-specific siRNA. Transfection with SPARC siRNA markedly inhibited the expression of SPARC protein in both H322 and A549 cells compared with the expression seen when control siRNA and mock-treated cells were used (Fig. 4A). Cell viability in H322 and A549 cells was determined after treatment with SPARC siRNA or control siRNA, and results showed that knockdown of SPARC did not affect cell viability compared with viability in parental- and control siRNA–treated cells (data not shown). Nevertheless, in vitro cell invasion analysis performed on Matrigel showed that knockdown of SPARC extensively suppressed cell invasion in both H322 and A549 cells, compared with cells treated with control siRNA or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (parental cells) (Fig. 4B). These results, like those observed in glioma and prostate cancer, suggested that SPARC plays an important role in cell migration and invasion in lung cancer cells.

Fig. 4. Effects of SPARC siRNA in cell invasion.

(A) Western blots of SPARC expression at 48 hours after treatment with siRNA. Parental and KLF4-transfected cells were used as controls. (B) Effect of SPARC siRNA on lung cancer cell invasion. Values represent mean + SD number of cells/field in three transwells. The experiment was repeated at least twice with similar results. *, P < 0.01 among the groups.

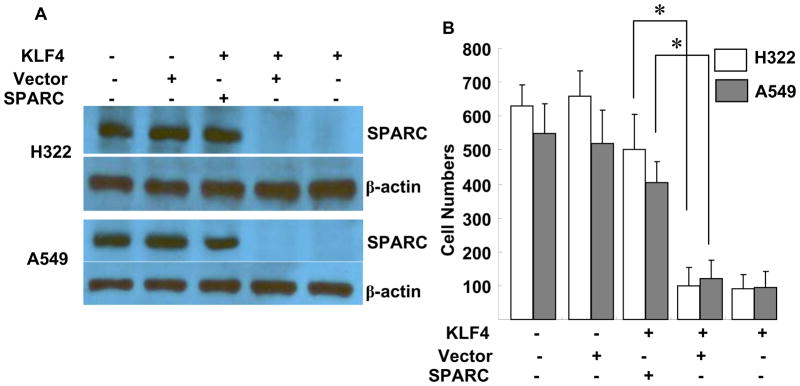

Enforced expression of SPARC restores KLF4-mediated inhibition of cell invasion

To further determine the role of SPARC in KLF4-mediated anti-invasion activity, we introduced SPARC cDNA via retrovirus-mediated gene transfer to H322 and A549 cells stably transfected with KLF4. A retrovirus expressing the GAPDH gene was used as a vector control. The SPARC retroviral vector effectively restored SPARC expression in KLF4-transfected H322 and A549 cells (Fig. 5A). The in vitro Matrigel cell-invasion assay showed that restoration of SPARC expression in KLF4-transfected H322 and A549 cells restored the cells’ invasion ability, similar to the results seen in parental H322 and A549 cells (Fig. 5B). These results indicated that KLF4-induced suppression of SPARC expression is critical for KLF4-mediated inhibition of lung cancer cell invasion.

Fig. 5. Enforced expression of SPARC in KLF4-transfected cells.

(A) Western blots of SPARC expression. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Number of invaded cells/field in three transwells. Values represent mean + SD number of cells/field. The experiment was repeated at least twice with similar results. *, P < 0.01 among the groups.

Discussion

Our results demonstrated that ectopic expression of KLF4 inhibited lung cancer cell invasion in vitro and that KLF4-mediated anti-invasion activity is caused by inhibition of SPARC gene expression. The role of the SPARC gene in cancer cell invasion and cancer metastasis has been studied by several groups, and accumulating evidence has shown that SPARC promotes cancer cell invasion and metastasis in glioma, melanoma, and prostate cancer. 4,14,34 Although the role of SPARC in lung cancer invasion and metastasis was not well characterized previously, SPARC had been extensively induced by treating bronchial epithelial cells with cigarette smoke condensate 36 High levels of SPARC expression had been observed in the stroma of patients with non–small cell lung cancer 13,36 and had been associated with nodal metastasis and poor prognosis 13 suggesting that SPARC may play a role in lung cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Our results showed that down-regulation of SPARC, either by siRNA or by ectopic expression of KLF4, suppressed lung cancer cell invasion, providing direct evidence of the role of SPARC in lung cancer cell invasion.

Despite many reports about the association between SPARC gene expression and cancer progression, little is known about the regulation of SPARC expression. Aberrant SPARC promoter methylation has been reported in lung cancer and colon cancer 37,38 In contrast, c-Jun has been reported to induce SPARC in MCF7 breast cancer cells 39 but to suppress SPARC expression in rat embryo fibroblasts, 40 suggesting that transcriptional factors involved in SPARC regulation might be species- or cell type–specific. Our study showed that SPARC expression in lung cancer cells was extensively suppressed by ectopic expression of KLF4, which was found to be down-regulated in lung cancer tissues,29 thus, indicating that KLF4 is a negative regulator of SPARC in lung cancer.

Moreover, the apparent inhibitory effect of KLF4 on lung cancer cell invasion led us to test its effect on invasion-related genes. Among the 12 genes tested, SPARC was the only one that was extensively suppressed by KLF4 in both H322 and A549 cells. Knockdown of SPARC by siRNA also inhibited lung cancer cell invasion, as observed in KLF4 overexpression. Furthermore, restoration of SPARC expression in KLF4-transfected cells abrogated KLF4-mediated anti-invasion activity. Thus, SPARC is one of the major downstream molecules of KLF4-induced anti-invasion activity in lung cancer cells.

KLF4 is a zinc-finger transcription factor of the SP/KLF family of transcriptional factors, which includes three domains of Kruppel-like zinc fingers. All of the members of the SP/KLF family of transcriptional factors can recognize and specifically bind to GC-rich sequences 41 thereby regulating various target genes involved in differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis. Evidence has shown that KLF4 competes with SP1 in promoter binding and suppresses the expression of SP1-regulated genes such as cyclin D1 and ornithine decarboxylase 42,43 Whether KLF4 regulates SPARC through a similar mechanism remains to be determined, however, the SP1 consensus sequence was identified in the SPARC promoter. 39,44 The expression of KLF4 itself is frequently lost in various human cancer types, such as gastric, 25 colorectal,45 esophageal squamous cell, 46 intestinal, 47 prostate, 48 bladder 49 and lung cancers; 29 of interest, SPARC was reportedly overexpressed in many of these cancers. Whether increased expression of SPARC in these cancers is caused by loss of KLF4 function is not clear. Nevertheless, our results showed that at least in some lung cancer cells, SPARC expression is negatively regulated by KLF4 and that KLF4 may execute its anti-invasion function by suppressing SPARC expression.

Materials and Methods

Human lung cancer cell lines

Lung cancer cell lines A549 and H322 are maintained in our laboratory. They are routinely cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (penicillin G at 100 units/mL and streptomycin at 100 μg/mL) and incubated at 37°C under regular culture conditions of 100% humidity, 95% air, and 5% CO2.

Retrovirus-mediated gene transfection

Plasmids containing coding sequences for KLF4, SPARC, and P21 were obtained either from OriGene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD) or from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The coding sequences were cloned to pBabe-based retrovirus plasmids with either puromycin or neomycin as a selection marker for mammalian cells. (Detailed cloning procedures and plasmid maps are available upon request.) The plasmids were then transfected to 293/Phoenix cells by using FuGENE HD reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Retroviral vectors were collected from a culture medium of 293/Phoenix cells at 48 to 72 hours after transfection and used to infect lung cancer cells. After selection with geneticin or puromycin (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) for 2 weeks, the positive clones were further studied.

Cell-invasion assay

The Matrigel-based in vitro cell-invasion assay was performed by using a Falcon cell culture insert with reconstituted basement membrane matrix (Matrigel, Becton-Dickinson Biosciences, NJ). Cells suspended in DMEM containing 1% FBS were seeded onto the upper sides of insert filters coated with Matrigel (60 μg/insert) at a density of 1 × 105 cells/insert. The lower compartment of the Falcon 24-well plates contained 600 μL of DMEM medium with 10% FBS and 5 μg/mL fibronectin. After 24–48 hours at 37°C under the regular culture condition, the noninvading cells on the upper side of the chamber membranes were removed with a cotton swab. The lower surfaces of the culture inserts were fixed with 5% glutaraldehyde and stained with 5% Giemsa. The number of invading cells on the opposite side of the chamber membranes was counted on each of three transwells.

Cell-viability assay

Cell viability was determined by using the sulforhodamine B assay, as described previously. 50 In brief, 3 × 103 cells were seeded in each well of 96-well flat-bottom plates and incubated for 24 hours. Next, SPARC siRNA and control siRNA were transfected, as described below. At 72 hours after incubation, 70 μL of 0.4% sulforhodamine B (w/v) in 1% acetic acid solution was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for an additional 60 minutes. The culture medium was removed, bound sulforhodamine B was solubilized with 100–200 μL of 10 mM unbuffered Tris-base solution (pH, 10.5), and absorbance was read on a multidetection microplate reader (Synergy HT, BIO-TEK Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT) at 570 nm. Relative cell viability was determined by setting the viability of the control cells at 100% and comparing the viability of the treated cells with that of the controls. Each experiment was performed in quadruplicate and repeated at least twice.

Gene knockdown with siRNA

The siRNA for human SPARC coding sequence (GenBank accession No. NM_003118) was obtained from Dharmacon Research, Inc. (Chicago, IL). The forward and reverse RNA strands were CGA UGU UGU CAA GGA UGG U dtdt and GCU ACA ACA GUU CCU ACC A dtdt, respectively. A control siRNA for random sequence UGA GAC CGA AGU UUU GGG U dtdt was also obtained from Dharmacon Research, Inc. For siRNA transfection, 10 μL of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, San Diego) was mixed with 500 μL of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, Carlbad) and then mixed with 200 pmol siRNA diluted in 500 μL of Opti-MEM. After incubation at room temperature for 20 minutes, the mixture was added to 60-mm plates with 5 mL of fresh medium. The cells were incubated at 37°C under regular conditions for indicated times before analysis.

Real-time absolute quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (Real-time AqRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). 1 μg of RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed in a 20 μL reaction volume with use of the Taqman reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNAs were diluted and quantified for expression of above given gene using real-time PCR (SYBR Green I) performed by Ziren Research LLC (Irvine, CA), with use of a single standard for getting the absolute ratio of each target and reference gene expressions, the procedure was performed as previously described.51, 33 The primer sequences for KLF4, SPARC, MMP1, MMP9, TERT, PKLR, IL3RA, VEGFA, RHOC, TGFB1, IGF1, VCAM1, PLAU, ADAMTS1, and ACTB (β-actin used as internal reference gene) are available from Ziren Research LLC (www.zirenresearch.com) upon request.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as previously described 29 with antibodies for KLF4, P21, SPARC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), and β-actin (Sigma Co., St. Louis, MO).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed by using Statistica software (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK) for comparisons among groups. The Student’s t test was used for comparison between two groups. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tamara Locke for editorial review. This work is supported by National Cancer Institute grants: R01CA-092487 (B. Fang), RO1CA-124951 (B. Fang), Lung SPORE Developmental Award 5P50CA-070907-100007 (S. Swisher), National Institutes of Health Core Grant 3P30CA-016672-32S3, the Homer Flower Gene Therapy Research Fund, the Charles Rogers Gene Therapy Fund, the Flora & Stuart Mason Lung Cancer Research Fund, the Charles B. Swank Memorial Fund for Esophageal Cancer Research, the George O. Sweeney Fund for Esophageal Cancer Research, the Phalan Thoracic Gene Therapy Fund, and the M. W. Elkins Endowed Fund for Thoracic Surgical Oncology.

References

- 1.Termine JD, Kleinman HK, Whitson SW, Conn KM, McGarvey ML, Martin GR. Osteonectin, a bone-specific protein linking mineral to collagen. Cell. 1981;26:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massi D, Franchi A, Borgognoni L, Reali UM, Santucci M. Osteonectin expression correlates with clinical outcome in thin cutaneous malignant melanomas. Human Pathol. 1999;30:339–344. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rich JN, Shi Q, Hjelmeland M, Cummings TJ, Kuan CT, Bigner DD, et al. Bone-related genes expressed in advanced malignancies induce invasion and metastasis in a genetically defined human cancer model. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15951–15957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz C, Lemke N, Ge S, Golembieski WA, Rempel SA. Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine promotes glioma invasion and delays tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6270–6277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellahcene A, Castronovo V. Increased expression of osteonectin and osteopontin, two bone matrix proteins, in human breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones C, Mackay A, Grigoriadis A, Cossu A, Reis-Filho JS, Fulford L, et al. Expression profiling of purified normal human luminal and myoepithelial breast cells: identification of novel prognostic markers for breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3037–3045. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas R, True LD, Bassuk JA, Lange PH, Vessella RL. Differential expression of osteonectin/SPARC during human prostate cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1140–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Bail B, Faouzi S, Boussarie L, Guirouilh J, Blanc JF, Carles J, et al. Osteonectin/SPARC is overexpressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pathol. 1999;189:46–52. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<46::AID-PATH392>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prenzel KL, Warnecke-Eberz U, Xi H, Brabender J, Baldus SE, Bollschweiler E, et al. Significant overexpression of SPARC/osteonectin mRNA in pancreatic cancer compared to cancer of the papilla of Vater. Oncol Reports. 2006;15:1397–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamanaka M, Kanda K, Li NC, Fukumori T, Oka N, Kanayama HO, et al. Analysis of the gene expression of SPARC and its prognostic value for bladder cancer. J Urol. 2001;166:2495–2499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato Y, Nagashima Y, Baba Y, Kawano T, Furukawa M, Kubota A, et al. Expression of SPARC in tongue carcinoma of stage II is associated with poor prognosis: an immunohistochemical study of 86 cases. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chin D, Boyle GM, Williams RM, Ferguson K, Pandeya N, Pedley J, et al. Novel markers for poor prognosis in head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:789–797. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Brekken RA, Sivridis E, Gatter KC, Harris AL, et al. Enhanced expression of SPARC/osteonectin in the tumor-associated stroma of non-small cell lung cancer is correlated with markers of hypoxia/acidity and with poor prognosis of patients. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5376–5380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robert G, Gaggioli C, Bailet O, Chavey C, Abbe P, Aberdam E, et al. SPARC represses E-cadherin and induces mesenchymal transition during melanoma development. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7516–7523. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smit DJ, Gardiner BB, Sturm RA. Osteonectin downregulates E-cadherin, induces osteopontin and focal adhesion kinase activity stimulating an invasive melanoma phenotype. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2653–2660. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sosa MS, Girotti MR, Salvatierra E, Prada F, de Olmo JA, Gallango SJ, et al. Proteomic analysis identified N-cadherin, clusterin, and HSP27 as mediators of SPARC (secreted protein, acidic and rich in cysteines) activity in melanoma cells. Proteomics. 2007;7:4123–4134. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Q, Bao S, Song L, Wu Q, Bigner DD, Hjelmeland AB, et al. Targeting SPARC expression decreases glioma cellular survival and invasion associated with reduced activities of FAK and ILK kinases. Oncogene. 2007;26:4084–4094. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weaver MS, Workman G, Sage EH. The copper binding domain of SPARC mediates cell survival in vitro via interaction with integrin beta1 and activation of integrin-linked kinase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22826–22837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706563200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane TF, Iruela-Arispe ML, Johnson RS, Sage EH. SPARC is a source of copper-binding peptides that stimulate angiogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:929–943. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.4.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ledda MF, Adris S, Bravo AI, Kairiyama C, Bover L, Chernajovsky Y, et al. Suppression of SPARC expression by antisense RNA abrogates the tumorigenicity of human melanoma cells. Nature Med. 1997;3:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang E, Kang HJ, Koh KH, Rhee H, Kim NK, Kim H. Frequent inactivation of SPARC by promoter hypermethylation in colon cancers. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:567–575. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porte H, Chastre E, Prevot S, Nordlinger B, Empereur S, Basset P, et al. Neoplastic progression of human colorectal cancer is associated with overexpression of the stromelysin-3 and BM-40/SPARC genes. Int J Cancer. 1995;64:70–75. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910640114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yiu GK, Chan WY, Ng SW, Chan PS, Cheung KK, Berkowitz RS, et al. SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine) induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:609–622. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61732-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koblinski JE, Kaplan-Singer BR, VanOsdol SJ, Wu M, Engbring JA, Wang S, et al. Endogenous osteonectin/SPARC/BM-40 expression inhibits MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7370–7377. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei D, Gong W, Kanai M, Schlunk C, Wang L, Yao JC, et al. Drastic down-regulation of Kruppel-like factor 4 expression is critical in human gastric cancer development and progression. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2746–2754. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei D, Kanai M, Jia Z, Le X, Xie K. Kruppel-like factor 4 induces p27Kip1 expression in and suppresses the growth and metastasis of human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4631–4639. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black AR, Black JD, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Sp1 and kruppel-like factor family of transcription factors in cell growth regulation and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2001;188:143–160. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu W, Hofstetter W, Li H, Zhou Y, He Y, Pataer A, et al. Putative Tumor-Suppressor Function of Krüppel-Like Factor 4 in Primary Lung Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5688–5695. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowland BD, Peeper DS, Rowland BD, Peeper DS. KLF4, p21 and context-dependent opposing forces in cancer. Nature Rev Cancer. 2006;6:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang W, Geiman DE, Shields JM, Dang DT, Mahatan CS, Kaestner KH, et al. The gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor (Kruppel-like factor 4) mediates the transactivating effect of p53 on the p21WAF1/Cip1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18391–18398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000062200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duffy MJ, McGowan PM, Gallagher WM. Cancer invasion and metastasis: changing views. J Pathol. 2008;214:283–293. doi: 10.1002/path.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behmoaram E, Bijian K, Bismar TA, Alaoui-Jamali MA. Early stage cancer cell invasion: signaling, biomarkers and therapeutic targeting. Front Biosci. 2008;13:6314–6325. doi: 10.2741/3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacob K, Webber M, Benayahu D, Kleinman HK. Osteonectin promotes prostate cancer cell migration and invasion: a possible mechanism for metastasis to bone. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4453–4457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Podhajcer OL, Benedetti LG, Girotti MR, Prada F, Salvatierra E, Llera AS. The role of the matricellular protein SPARC in the dynamic interaction between the tumor and the host. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:691–705. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siddiq F, Sarkar FH, Wali A, Pass HI, Lonardo F. Increased osteonectin expression is associated with malignant transformation and tumor associated fibrosis in the lung. Lung Cancer. 2004;45:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheetham S, Tang MJ, Mesak F, Kennecke H, Owen D, Tai IT. SPARC promoter hypermethylation in colorectal cancers can be reversed by 5-Aza-2′deoxycytidine to increase SPARC expression and improve therapy response. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1810–1819. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki M, Hao C, Takahashi T, Shigematsu H, Shivapurkar N, Sathyanarayana UG, et al. Aberrant methylation of SPARC in human lung cancers. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:942–948. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 39.Briggs J, Chamboredon S, Castellazzi M, Kerry JA, Bos TJ. Transcriptional upregulation of SPARC, in response to c-Jun overexpression, contributes to increased motility and invasion of MCF7 breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:7077–7091. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mettouchi A, Cabon F, Montreau N, Vernier P, Mercier G, Blangy D, et al. SPARC and thrombospondin genes are repressed by the c-jun oncogene in rat embryo fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1994;13:5668–5678. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Philipsen S, Suske G. A tale of three fingers: the family of mammalian Sp/XKLF transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2991–3000. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.15.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shie JL, Chen ZY, Fu M, Pestell RG, Tseng CC. Gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor represses cyclin D1 promoter activity through Sp1 motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2969–2976. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.15.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen ZY, Shie JL, Tseng CC. Gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor represses ornithine decarboxylase gene expression and functions as checkpoint regulator in colonic cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46831–46839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young MF, Findlay DM, Dominguez P, Burbelo PD, McQuillan C, Kopp JB, et al. Osteonectin promoter. DNA sequence analysis and S1 endonuclease site potentially associated with transcriptional control in bone cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:450–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao W, Hisamuddin IM, Nandan MO, Babbin BA, Lamb NE, Yang VW. Identification of Kruppel-like factor 4 as a potential tumor suppressor gene in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:395–402. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y, Goldstein BG, Chao HH, Katz JP. KLF4 and KLF5 regulate proliferation, apoptosis and invasion in esophageal cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:1216–1221. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.11.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ton-That H, Kaestner KH, Shields JM, Mahatanankoon CS, Yang VW. Expression of the gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor gene during development and intestinal tumorigenesis. FEBS Lett. 1997;419:239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01465-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schulz WA, Hatina J. Epigenetics of prostate cancer: beyond DNA methylation. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:100–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohnishi S, Ohnami S, Laub F, Aoki K, Suzuki K, Kanai Y, et al. Downregulation and growth inhibitory effect of epithelial-type Kruppel-like transcription factor KLF4, but not KLF5, in bladder cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308:251–256. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo W, Wu S, Liu J, Fang B. Identification of a small molecule with synthetic lethality for K-ras and protein kinase C iota. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7403–7408. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou YH, Hess KR, Liu L, Linskey ME, Yung WK. Modeling prognosis for patients with malignant astrocytic gliomas: quantifying the expression of multiple genetic markers and clinical variables. Neuro-Oncol. 2005;7:485–494. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704000730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]