Abstract

Double hydrophilic copolymers with one polyethylene glycol (PEG) block and one β-cyclodextrin β-CD) flanking block (PEG-b-PCDs) were synthesized through the post-modification of macromolecules. The self-assembly of PEG-b-PCDs in aqueous solutions was initially studied by a fluorescence technique. This measurement together with AFM and TEM characterization demonstrated the formation of nanoparticles in the presence of lipophilic small molecules. The host-guest interaction between the β-CD unit of a host copolymer and the hydrophobic group of a guest molecule was found to be the driving force for the observed self-assembly. This spontaneous assembly upon loading of guest molecules was also observed for hydrophobic drugs with various chemical structures. Relatively high drug loading was achieved by this approach. Desirable encapsulation was also achieved for the hydrophobic drugs that cannot efficiently interact with free β-CD. In vitro release studies suggested that the payload in nano-assemblies could be released in a sustained manner. In addition, both the fluorescence measurement and the in vitro drug release studies suggested that these nano-assemblies mediated by the inclusion complexation exhibited a chemical sensitivity. The release of payload can be accelerated upon the triggering by hydrophobic guest molecules or free β-CD molecules. These results support the potential applications of the synthesized copolymers for the delivery of hydrophobic drugs.

Keywords: Host-guest interactions, β-Cyclodextrin, Nano-assemblies, Chemical sensitivity, Drug delivery

1. Introduction

Nano-systems assembled by macromolecular amphiphiles have attracted great attention due to their wide applications in areas such as pharmaceutics, bioengineering, medical diagnosis and gene therapy[1–4]. Polymeric micelles with core-shell architecture are among the most widely studied nanocarriers for the delivery of hydrophobic therapeutics[5–11]. Several micellar formulations of antitumor drugs have been intensively studied in preclinical and clinical trials, and their efficacy has been demonstrated [12–15]. Generally, polymeric micelles with hydrophobic cores are assembled in an aqueous solution due to the hydrophobic interaction between core-forming segments. The hydrophobic inner core serves as a nano-container for hydrophobic drugs, while the outer shell of hydrophilic polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), provides the micelles with colloidal stability and extends the circulation time in the bloodstream after their systemic administration. Until now, most of the polymeric micelles with hydrophobic cores have been constructed using amphiphilic copolymers with block, graft, comb, branch or dendritic architecture[16, 17], in which the hydrophobic block/graft segments or groups were covalently linked with the hydrophilic segments. In addition, micelle-like nano-assemblies based on polyelectrolyte complex have been developed as delivery carriers. These assemblies are constructed by the complexation of double hydrophilic block copolymers containing ionic and nonionic blocks with oppositely charged molecules such as polyelectrolytes, proteins, surfactants, or metal ions. These novel nano-vehicles are now widely used for the delivery of genes, proteins, low molecular weight drugs and imaging agents[18–20].

More recently, the host-guest interactions between host and guest molecules have been adopted to assemble polymer nanoparticles for drug/gene delivery. Due to their excellent biocompatibility, cyclodextrins including α-cyclodextrin (α-CD), β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) and γ-cyclodextrin (γ-CD), have been widely used as host units to construct host-guest delivery carriers. For instance, excellent in vivo therapeutic efficacy has been observed for nanoparticles assembled from camptothecin-conjugated β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) polymers[21]. On the other hand, cationic β-CD polymers derived nanoparticles were found to be efficient non-viral delivery vectors for siRNA in humans[22]. Additionally, α-CD based polyrotaxanes have also been employed as delivery carriers [23–25]. To the best of our knowledge, fewer efforts have been made to fabricate host-guest assemblies based on a double hydrophilic copolymer and small molecules, in which inclusion interaction is the main driving force. Moreover, no delivery systems based on these types of assemblies have been developed this far.

The aim of this study was to prepare and evaluate a novel chemical sensitive nano-platform based on host-guest interactions for drug delivery. β-CD containing double hydrophilic block copolymers were synthesized. Self-assembly of this type of copolymers was studied in the presence of a series of small hydrophobic molecules, including several drugs with different chemical structures. The morphology, particle size and other physicochemical properties of this type of assemblies were explored. In addition, chemical responsive in vitro release behaviors were examined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

L-Aspartic acid β-benzyl ester was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA). Triphosgene was obtained from Fisher (USA). β-Benzyl-L-aspartate N-carboxyanhydride (BLA-NCA) was synthesized according to the literature [26]. α-Methoxy-ω-amino-polyethylene glycol (MPEG-NH2) with an average molecular weight (MW) of 5000 was purchased from Laysan Bio, Inc. (Alabama, USA), and used without further purification. Ethylenediamine (EDA) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA) and distilled over CaH2 under decreased pressure. Pyrene (≥99%) and β-cyclodextrin (β-C D, ≥98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (USA) and used as received. The method established by Baussanne et al. was employed to synthesize 6-monotosyl β-CD [27]. Pyrene, coumarin 102 (C102), ibuprofen (IBU), indomethacin (IND), rapamycin (RAP) and dexamethasone (DEX) were purchased form Sigma-Aldrich Co. (USA). Adamantane-1-carboxylic acid (ADCA, 97%) was purchased from Maybridge Trevillett (Tintagel, England).

2.2. Synthesis of PEG-b-polyaspartamide containing EDA units (PEG-b-PEDA)

Copolymer polyethylene glycol-block-poly(β-benzyl L-aspartate) (PEG-b-PBLA) copolymer was synthesized as reported by Harada et al[28]. Briefly, BLA-NCA was polymerized in DMF at 40ºC by the initiation from the terminal primary amino group of MPEG-NH2 to obtain PEG-b-PBLA. PEG-b-PEDA was prepared through the quantitative aminolysis reaction of PEG-b-PBLA in dry DMF at 40ºC in the presence of 50-fold molar excess of EDA[29]. After 48 h, the reaction mixture was dialyzed against deionized water (MWCO: 3500), and the final aqueous solution was lyophilized to a white powder.

2.3. Synthesis of PEG-b-PCD

PEG-b-PCD copolymers were synthesized by a slightly modified method established in our previous study [30]. Briefly, lyophilized PEG-b-PEDA and 5 fold excess of 6-monotosyl β-CD were reacted in anhydrous DMSO. After 5 days of the reaction, the polymer was purified by dialysis, and the resultant aqueous solution was lyophilized to a yellow to brown powder.

2.4. Preparation of host-guest assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD and small molecules

Assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD-3 and IND were prepared by three methods, i.e., dialysis, modified dialysis procedure and emulsion technique. For the dialysis method, both IND and PEG-b-PCD-3 with a weight ratio of 1:4 were co-dissolved in DMSO at 60ºC. This solution was placed into dialysis tubing (MWCO 6–8 kDa) for dialyzing against deionized water for 24 h at 25ºC, and then the dialysate was filtered through a 0.8 μm syringe filter. For the modified dialysis procedure, 1 ml DMSO solution containing 5 mg IND was added dropwise into 2 ml aqueous solution containing 20 mg PEG-b-PCD-3 under bath sonication. Then, similar dialysis and filtration procedures were carried out. In the case of the emulsion technique, 0.3 ml dichloromethane containing 5 mg IND was emulsified into 3 ml water containing 20 mg PEG-b-PCD-3 using a probe sonicator at an output power of 15 W (Virsonic 100, Cardiner, NY). The solvent was evaporated at room temperature for 12 h, and then the aqueous solution was filtered through a 0.8 μm syringe filter. For the assemblies containing other hydrophobic drugs, the above mentioned dialysis method was adopted.

2.5. In vitro release study

Lyophilized assemblies containing small molecular compound was dissolved into deionized water (10 mg/ml). 0.5 ml sample solution was placed into dialysis tubing, which was immersed in 30 ml 0.01M PBS (pH 7.4). At predetermined time intervals, 4.0 ml release medium was withdrawn, and fresh PBS was added. The concentration of the candidate drug in the release buffer was determined through UV measurement. The detection wavelength was 310, 280, 280, 265 and 265 nm for C102, IND, RAP, IBU and DEX, respectively. To study the chemical triggered release profiles, different chemicals including benzyl alcohol (0.1 mol/L), ADCA (10.0 mmol/L), IBU (1.0 mmol/L) and β-CD (1.0 mmol/L) of appropriate concentration were dissolved in 0.01M PBS (pH 7.4) to perform the release experiments.

2.6. Measurements

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian INOVA-400 spectrometer operating at 400 MHz. The Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass measurement was performed with a Waters Micromass TofSpec-2E run in linear mode. Dithranol (purchased from Aldrich Chemical) was used as a matrix, and tetrahydrofuran as a solvent for the matrix. The dried-droplet method was employed for the sample preparation. Using pyrene as a fluorophore, steady-state fluorescence spectra were measured on JASCO FP-6200 fluorescence spectrophotometer with a slit width of 5 nm for both excitation and emission. All spectra were run on air-equilibrated solutions. For the fluorescence emission spectra, the excitation wavelength was set at 339 nm, and for excitation spectra, the emission wavelength was 390 nm. The scanning rate was set at 125 nm/min. All tests were carried out at 25ºC. Sample solutions were prepared as described previously [31].

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements for the assemblies in aqueous solutions were performed with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument at 25ºC. The atomic force microscopy (AFM) observation was carried out on a NanoScope IIIa-Phase Atomic Force Microscope connected to a NanoScope IIIa Controller using an EV scanner. Samples were prepared by drop-casting the diluted solution onto freshly cleaved mica. All the images were acquired under a tapping mode. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation was carried out on a JEOL-3011 high resolution electron microscope operating at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV. Samples were prepared at 25ºC by dipping the grid into the aqueous solution of assemblies, and the extra solution was blotted with filter paper. After the water was evaporated at room temperature for several days, the samples were observed directly without staining. Formvar coated copper grids, stabilized with evaporated carbon film, were used.

2.7. Calculation of the free energies of inclusion complexation

A group-contribution method established by Suzuki was employed to calculate the free energies (ΔG) of complexation between β-CD and various model drugs [32]. Briefly, the ΔG was estimated according to the following equation:

where 1χis the first order molecular connectivity index, Gi is the contribution of the group of type i, ni is the number of times this group occurs in the molecule, and the summation is carried over all type i.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Polymer synthesis

Double hydrophilic block copolymers with a PEG block and a block containing flanking β-cyclodextrin β-CD) were synthesized by a multi-step macromolecular substitution reaction (Scheme S1). PEG-b-PBLA was synthesized via a ring opening polymerization of BLA-NCA using MPEG-NH2 as an macromolecular initiator [28]. The degree of polymerization (DP) of PBLA was calculated from the 1H NMR spectroscopy based on the peak intensity of benzyl protons of PBLA side chains (7.3 ppm) to the methylene protons of the PEG block (3.6 ppm). PEG-b-PBLAs with various PBLA lengths were obtained by varying the molar ratio of PEG to BLA-NCA. PEG-b-PEDAs were synthesized by an aminolysis reaction of PEG-b-PBLA in the presence of excess EDA. β-CD was then covalently linked to the PEG-b-PEDA to obtain PEG-b-PCDs.

FT-IR spectra of various copolymers including PEG-b-PBLA, PEG-b-PEDA and PEG-b-PCDs were analyzed (Fig. S1a). After the aminolysis of PEG-b-PBLA by EDA, the absorption peak at 1737 cm−1 corresponding to carbonyl groups of PBLA disappeared, which suggested a nearly complete substitution between benzyl ester and EDA. This result agrees well with the 1H NMR spectra (Fig. S1b). The peak at 7.3 ppm corresponding to the protons of the benzyl group of PEG-b-PBLA vanished after the aminolysis reaction. This is consistent with the result reported by Kataoka’s group [29]. These results suggest that the copolymer PEG-b-PEDA was successfully synthesized. By the nucleophilic substitution between the amino group and the 6-monotosyl β-CD, β-CD was conjugated to PEG-b-PEDA. This is supported by the appearance of a significant absorption peak at 1029 cm−1 after the CD conjugation (Fig. S1a). In addition, the intensity of this peak increased significantly as more β-CD molecules were conjugated. The 1H NMR spectra of PEG-b-PCD copolymers (Fig. S1c) were consistent with the FT-IR results. The proton signals corresponding to β-CD were intensified as the length of CD-containing block was increased. From the combination of these measurements, we can conclude that the β-CD molecules were successfully introduced. The content of β-CD was calculated based on the 1H NMR spectra and the results are listed in Table 1. The resultant copolymers could be easily dissolved in water at room temperature.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of copolymers.

Calculated based on 1H NMR spectra.

3.2. Fluorescence study

To investigate the formation of polymeric assemblies mediated by the host-guest interaction between the PEG-b-PCDs and hydrophobic substances, pyrene was initially used as a fluorophore. Independent of the copolymer composition, a significant enhancement in the excimer intensity (420 to 600 nm) was observed with an increase in the PEG-b-PCD concentration (Figs. S2A-B I). The excimer formation, however, can not be observed in the case of β-CD solutions. This revealed the existence of pre-associated pyrene pairs in sample solutions, which is also supported by the broadening of the excitation band of pyrene in the presence of PEG-b-PCDs (Fig. S3) [33]. Additionally, a significant increase in the values of I338/I333, I3/I1 and IE/IM was observed for pyrene as the concentration of PEG-b-PCD increased to a certain point (Fig. S2A-B II). No significant changes, however, were found in the case of β-CD. Furthermore, the values of I3/I1 for the PEG-b-PCDs are significantly larger than those of β-CD, indicating that the pyrene molecules are located in a more hydrophobic microenvironment in the former systems [34]. Only the apolar cavity of β-CD should be responsible for the changes in the fluorescence spectra of pyrene molecules when β-CD is introduced. For the pyrene molecules in aqueous solutions of PEG-b-PCDs, in addition to the apolar cavity of β-CD, the association of pyrene molecules should also contribute to the enhanced local hydrophobicity as evidenced by the excimer formation. These results suggest that micelle-like assemblies might be formed by the pyrene molecules mediated assembly of PEG-b-PCDs. The cyclodextrin containing block, which can form the inclusion complex with pyrene, might construct the core of assemblies, while the extending PEG chains may serve as a hydrophilic shell.

3.3. Assemblies based on PEG-b-PCDs and hydrophobic small molecules

The above fluorescence results suggest the formation of micelle-assemblies by PEG-b-PCDs in the presence of pyrene molecules. To further elucidate the characteristics of this type of assemblies, pyrene/PEG-b-PCD-3 (containing a higher molecular weight block of PCD) assemblies were prepared by a dialysis method. A 3D AFM image of the PEG-b-PCD-3 assemblies containing pyrene (Fig. S4a) showed the assemblies to be round in shape with diameters in the range of 15 to 110 nm. AFM sectional analysis of a typical structure showed that the diameters of the assemblies were ten- to seventeen-times larger than the heights of the aggregates. This should be attributed to the flattening of spherical particles following adsorption onto the mica surface. In addition, the tip convolution effect should have also contributed to this phenomenon[35]. This is further confirmed by DLS and TEM measurements. The particle size of pyrene-containing assemblies was 60, 30 and 25 nm based on AFM, DLS and TEM measurements, respectively (Fig. S4c).

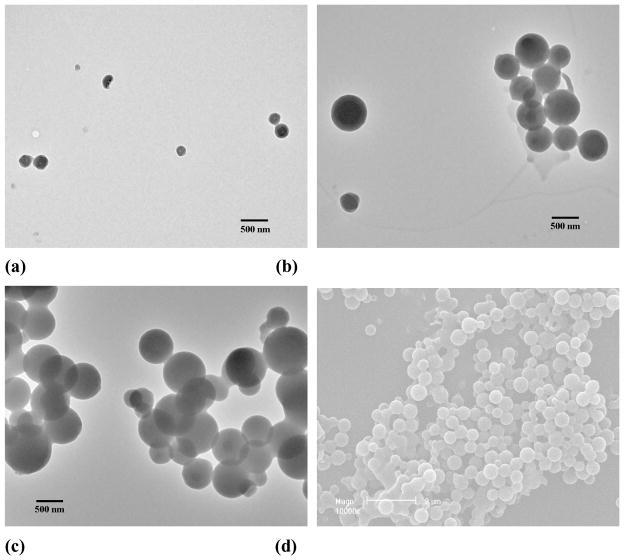

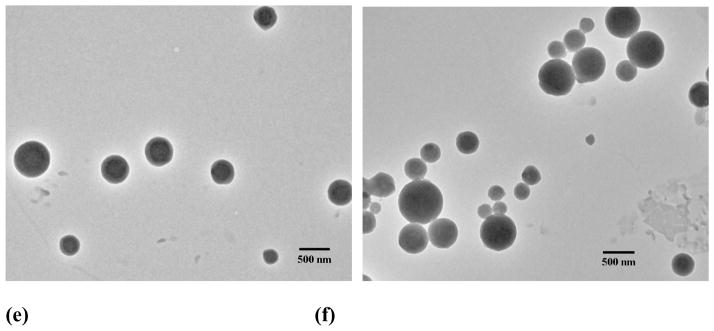

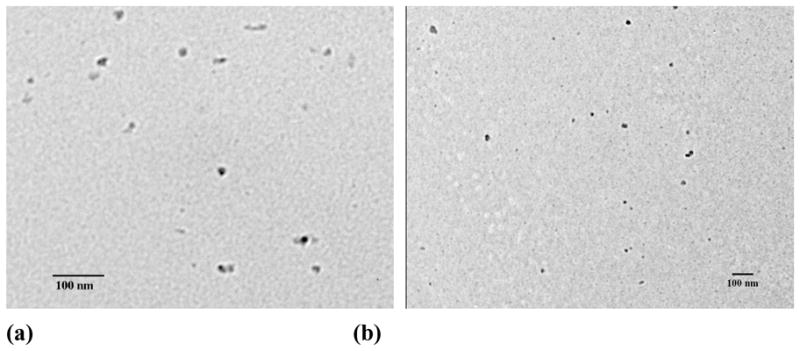

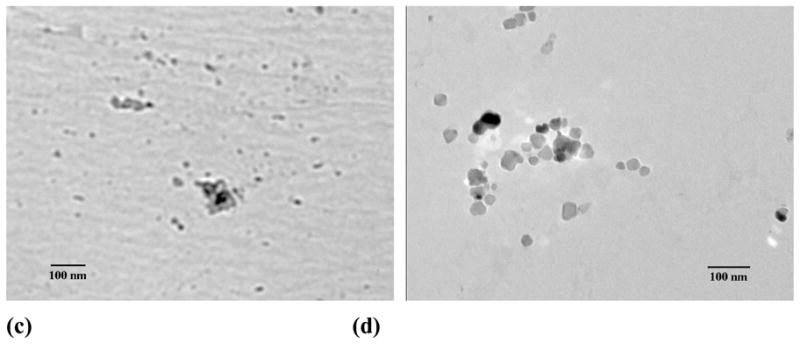

To demonstrate the feasibility of a simultaneous encapsulation and nanoparticle formation based on PEG-b-PCD-3 and other hydrophobic compounds, C102, IBU, IND, RAP, and DEX were selected as model drugs. Assemblies containing C102 were prepared by the same procedure as that for the pyrene-containing aggregates. The morphology and particle size were characterized by AFM, TEM and DLS. The AFM image (Fig. S4b) showed assemblies to be round with a number-average diameter of 140 nm. The DLS determination showed the number-average diameter to be 70 nm. This agrees with the TEM result (~40 nm, see Fig. S4d). The morphology of the assemblies containing IBU, IND, RAP and DEX were also observed using TEM. As shown in Fig. 1, nano-assemblies could be observed for all the drugs investigated here. Nearly spherical assemblies with sizes of 72.8, 50.9 and 63.6 nm were formed by PEG-b-PCD-3 in the presence of IBU, IND and RAP, respectively (Fig. S5). As for the assemblies containing DEX, irregular assemblies were observed as shown in Fig. 1d. The number-averaged size determined by DLS was 78.8 nm (Fig. S5a). In addition, the particle size was found to be significantly increased for RAP containing assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD-3 as illustrated by TEM and SEM images in Figs. 2a-d. The DLS measurement indicated the mean size to be 239.9, 464.4 and 520.7 nm for assemblies based on drug/polymer ratios of 3.5/20, 5.0/20, and 10.0/20, respectively (Fig. S5b). Furthermore, the polymer composition (PEG-b-PCD-1, PEG-b-PCD-2, or PEG-b-PCD-3) had no significant effect on RAP-loaded assemblies in terms of morphology and size (Fig. S5; also Figs. 2b, e, and f). The mean size of assemblies formulated with a RAP/polymer ratio of 5:20 was 464.4, 481.6 and 486.4 nm for PEG-b-PCD-3, −2 and −1, respectively.

Fig. 1.

TEM images of PEG-b-PCD-3 assemblies containing (a) IBU, (b) IND, (c) RAP, and (d) DEX. Dialysis method was employed to prepare drug containing assemblies. For all the drugs, the employed drug/polymer feed ratio was 2:20.

Fig. 2.

RAP containing assemblies based on PEG-b-PCDs. TEM images of PEG-b-PCD-3 derived assemblies with feed ratios of (a) 3.5:20, (b) 5:20 and (c) 10:20. (d) SEM image of assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD-3 with a feed ratio of 5:20. Assemblies originated from PEG-b-PCD-1 (e) and PEG-b-PCD-2 (f) with a feed ratio of 5:20.

In addition to the dialysis method, an emulsion solvent evaporation technique was also employed to prepare IND containing assemblies. Vesicle-like assemblies were obtained when the drug/polymer feed ratio was 3:15, while micellar nanoparticles were achieved when the feed ratio was increased to 6:15, as can be observed from TEM images (Fig. S6). The size of vesicles was significantly larger than that of micelles. The number-average size calculated based on TEM images was 50–200 nm and 15 nm for vesicles and micelles, respectively. These results suggested that polymeric micelles or vesicles can be assembled by PEG-b-PCD copolymers in the presence of hydrophobic drugs. The morphology of assemblies is dependent on the drug structure, drug loading content, and preparation procedure.

The dispersion behavior after the reconstitution from a freeze-dried formulation of nano-assemblies is an important issue for drug delivery [36]. As a preliminary stability study, the effect of freeze-drying/reconstitution on the size and morphology of assemblies was evaluated. For IND-containing assemblies prepared with a formulation ratio of 6:20, the mean size (by number) was 93.9 and 118.2 nm before and after lyophilization, respectively (Fig. S7a). The TEM images suggested that no significant change in the particle morphology had occurred after the reconstitution process (Figs. S7b-c). As for RAP-loaded particles, the morphology of the reconstituted assemblies after freeze-drying (Fig. S7d) did not change significantly compared with that before freeze-drying (Fig. 2a). These results suggest that the nanoparticles assembled by PEG-b-PCDs in the presence of lipophilic drugs are stably maintained through the freeze-drying/reconstitution process.

3.4. Chemical responsivity of assemblies

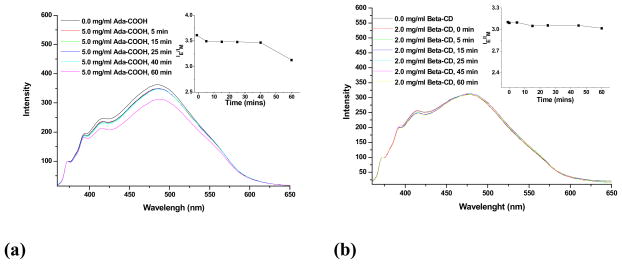

Due to the reversibility of the host-guest interaction between the β-CD and hydrophobic compounds, the supramolecular systems based on this non-covalent interaction frequently display chemical sensitivity. A preliminary fluorescence experiment was performed to investigate the chemical sensitivity of assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD-3 and pyrene. Fig. 3 shows the pyrene emission spectra in aqueous solutions of PEG-b-PCD-3 in the presence of various additives. One can observe that the intensity ratio (IE/IM) of the excimer to monomer decreased in a time dependent manner in the presence of ADCA (Fig. 3a). As aforementioned, the occurrence of pyrene excimer is a result of the excitation of pre-associated pyrene pairs. The intensity of the pyrene excimer should be related to the number of the ground-state dimers. A decrease in the excimer intensity means a reduction in the number of pyrene dimers. In other words, ADCA molecules will compete with pyrene molecules to interact with the CD units in the PEG-b-PCD copolymer. As well documented, compared with other hydrophobic groups the adamantanyl group displays an extremely high complexation constant with β-CD [37]. As a result, the presence of ADCA will induce the release of pyrene molecules from the cores of assemblies. A slight decrease in IE/IM values can also be observed from pyrene emission in the presence of β-CD (Fig. 3b), which indicated that β-CD can also induce a slight dissociation of pyrene molecules from the core. However, this effect seemed not to be very large, which might be due to the limited diffusion of β-CD molecules through PEG shell into the core of PEG-b-PCD assemblies. As a summary, these results suggested that assemblies based on PEG-b-PCDs and hydrophobic compounds possess chemical-responsive capacity to molecules that are competitors of either core-forming guest compounds or the host polymer.

Fig. 3.

Pyrene emission spectra in the aqueous solutions of PEG-b-PCD-3 in the presence of various additives (a) ADCA, polymer concentration was 2.0 mg/ml; and (b) β-CD, polymer concentration was 1.5 mg/ml.

3.5. Host-guest complexation and drug encapsulation

As well known, the host-guest complexation between β-CD and guest molecules allows β-CD to be used in numerous fields such as industry, pharmaceutics, agriculture and biotechnology. The information on the complexation capability and thermodynamic stability of cyclodextrin with guest molecules is necessary to determine whether or not a host-guest complexation is useful in a particular application. According to the equation ΔG = − RT ln K, the free energy of the inclusion complexation is directly related to the binding constant. The ΔG between β-CD and several model drugs was therefore calculated. As listed in Table 2, the selected guest molecules exhibit ΔG values ranging from −33.7 to 20.8 kJ/mol. Since a large positive value of ΔG means a weak inclusion interaction, the RAP should be a poor guest molecule to be solubilized by β-CD. However, the encapsulation results suggested that a high loading efficiency can be achieved for various compounds with significantly different binding free energies. Even for RAP with a larger positive value of ΔG, an efficient encapsulation accompanying the formation of nano-assemblies was observed. These results suggested that the complexation ability of β-CD units in PEG-b-PCD was significantly enhanced compared with that of β-CD itself. The inclusion interactions from multiple β-CD units in one or several macromolecular chains may have synergistically enhanced solubilization of guest molecules. This may be especially true for the guest compounds with a larger molecular volume.

Table 2.

Quantitative structure-properties relationship for various drugs.

| Drug | Chemical structure | Structure with minimized energy | ΔG (KJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C102 |  |

|

−17.9 |

| IBU |  |

|

−23.4 |

| IND |  |

|

−16.0 |

| DEX |  |

|

−33.7 |

| RAP |  |

|

20.8 |

The results of the drug encapsulation are summarized in Table 3. The loading efficiency was closely related with the chemical structure of drug molecules. A higher efficiency was achieved for molecules that have higher binding constant with β-CD, as observed for IBU and DEX. Although a lower loading efficiency of 56.0% was found for the RAP, an increase in the RAP feed can still enhance the loading content. The preparation method also influenced the encapsulation efficiency. As demonstrated for IND, the preparation of assemblies via emulsion solvent evaporation technique resulted in a relatively high drug loading. No significant difference in the IND loading, however, was found between the dialysis and modified dialysis method (Table 3). In addition, the chain length of the PCD block is another factor governing the drug loading capacity as shown for RAP in Table 3. A longer PCD block exhibits stronger interactions with guest molecules, and higher drug loading can therefore be achieved.

Table 3.

The effect of drug structure, drug feed and preparation procedure on the drug loading and loading efficiency (n=3). Dialysis method was employed unless it is noted.

| Polymer | Drug | Drug feed (%) | Loading Content (%) | Loading efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-b-PCD-3 | IBU | 9.1% | 8.0±1.3% | 87.9±14.3% |

| IND | 5.7±0.6% | 62.6±6.6% | ||

| RAP | 5.1±1.1% | 56.0±12.1% | ||

| DEX | 8.2±0.8% | 90.1±8.8% | ||

| 17.0±1.3% a | 85.0±6.5% a | |||

| IND | 20.0% | 13.4±1.7% b | 67.0±8.5% b | |

| 14.0±1.8% c | 70.0±9.0% c | |||

| 14.9% | 10.5±1.2% | 70.5±8.1% | ||

| RAP | 20.0% | 16.2±2.6% | 81.0±13.0% | |

| 33.3% | 27.2±3.5% | 81.7±10.5% | ||

| PEG-b-PCD-2 | RAP | 20.0% | 9.3±2.1% | 46.5±10.5% |

| PEG-b-PCD-1 | 8.4±2.5% | 42.0±12.5% |

Emulsion solvent evaporation technique;

Modified dialysis method;

Dialysis method.

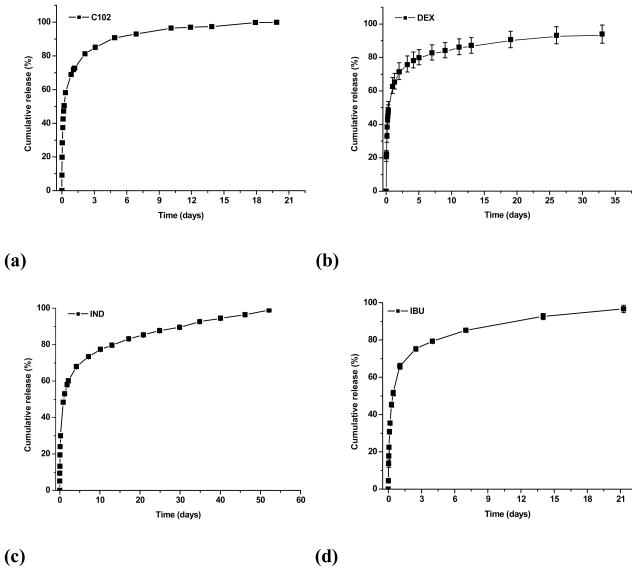

3.6. In vitro release study

For a certain drug delivery system, the in vitro release behavior is a very good indication of the in vivo pharmacokinetics and bio-distribution of the drug after its administration. Fig. 4 shows in vitro release profiles of PEG-b-PCD-3 derived assemblies containing various model drugs. Generally, for all these drugs, a biphasic release profile can be observed, in which a rapid release stage is followed by a sustained release phase. The rapid phase should be due to the release of free drug molecules and the drugs that are physically encapsulated into the cores through non-inclusion interactions. For the drug molecules that are associated with cyclodextrin units by the inclusion interactions, the release occurs through a slower dissociation and diffusion. As a consequence, a slowed release stage was observed. However, the release rate was found to be different for different drugs. For instance, above 95% C102 was released within 10 days, while less than 80% IND released within the same period. More sustained release profiles were observed for DMS and IND. A brief comparison of ΔG values between various guest compounds suggested that the drug release behavior of PEG-b-PCDs based assemblies is not solely related to the binding energy. Other factors such as the drug solubility, molecular volume and the morphology of assemblies also contributed to the observed release characteristics. Different release behaviors were also observed for the assemblies based on various methods. IND loaded assemblies prepared using the emulsion technique exhibited a more rapid release (Fig. S8). In comparison to the dialysis procedure, the modified dialysis procedure led to a slightly increased drug release rate. These results, however, also indicate that most drugs exhibited a relatively high burst release from PEG-b-PCD based assemblies. This is not surprising considering their submicron size and the hydrophilic nature of the PEG-b-PCD copolymers. Although the burst release is helpful to achieve an effective concentration for therapy, it can become problematic when the initial concentration is higher than the toxic dosage. Consequently, the candidate drugs should be carefully selected based on their therapeutic potency, toxicity as well as other physicochemical properties. On the other hand, the release profiles of these assemblies can be optimized by co-incorporating a hydrophobic guest polymer that can modify the characteristics of the core. This is feasible because the drug release profiles of micellar formulations of amphiphilic copolymers are mainly dominated by the characteristics of the micellar core.

Fig. 4.

In vitro release profiles of PEG-b-PCD-3 based assemblies containing various drugs (a) C102, (b) DEX, (c) IND, and (d) IBU.

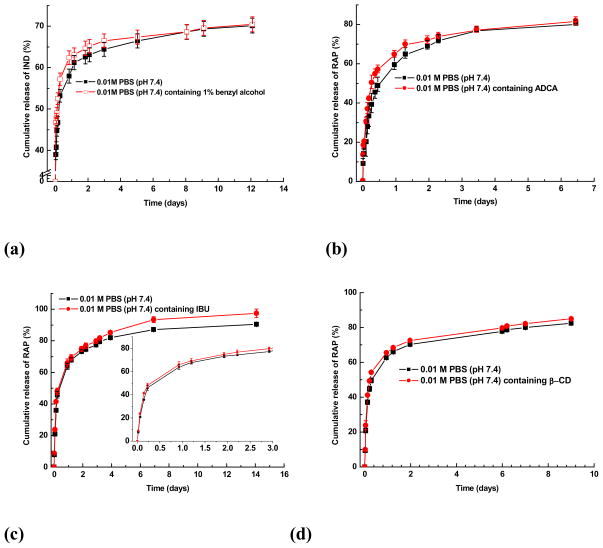

As demonstrated in the fluorescence study, PEG-b-PCD based nano-assemblies exhibit a chemical sensitivity. To substantiate the potential application of these chemically responsive assemblies, in vitro release studies were carried out in the presence of various chemical stimuli. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, accelerated drug release occurred in the initial release stage for IND in the presence of a competitive molecule benzyl alcohol. This effect, however, leveled off after this initial stage. A similar stimulated release profile was observed for RAP in the presence of ADCA, another competitive compound (Fig. 5b). Additionally, an enhancement on the release rate of RAP was also observed in the presence of another hydrophobic drug IBU (Fig. 5c). This suggested that the release of one drug from PEG-b-PCDs based assemblies could be accelerated by another drug. In addition to the competitive compounds against guest molecules, free β-CD can serve as a competitor of host polymer to speed the release of guest molecules (Fig. 5d). This chemically responsive acceleration of drug release is consistent with the aforementioned fluorescence result. All of these results point to the fact that the release of a guest molecule from PEG-b-PCD based assemblies can be chemically stimulated by a competitive compound.

Fig. 5.

In vitro release profiles of PEG-b-PCD-3 based assemblies in the presence of various chemicals.

4. Conclusions

The formation of nano-assemblies by double hydrophilic copolymers with one PEG block and one β-CD containing block was demonstrated in the presence of various hydrophobic compounds. AFM, TEM and SEM examinations indicated the morphology of the assemblies to be spherical. The size of the assemblies changed with the chemical structure of the guest molecule and the preparation method employed. Various hydrophobic drugs can be efficiently loaded during the nanoparticle formation, with the encapsulation efficiency dominated by the drug structure and preparation procedure. In vitro release studies indicated that the payload in PEG-b-PCD nano-assemblies can be released in a sustained manner. The chemical structure of drugs and preparation technique influence the release rate. In addition, a chemically stimulated acceleration on drug release was found for these types of assemblies in the presence of a competitive compound. This preliminary study substantiates the potential applications of assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD copolymers as a novel nano-platform for the delivery of hydrophobic bioactive compounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from the NIH (NIDCR DE015384 & DE017689, NIGMS GM075840). The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Kenichi Kuroda of Department of Biologic and Materials Sciences of the University of Michigan for sharing the fluorescence spectrophotometer. The authors are grateful to Dr. Nicholas A. Kotov in the Department of Chemical Engineering of the University of Michigan for sharing the DLS instrument.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wu Y, Sefah K, Liu H, Wang R, Tan W. DNA aptamer–micelle as an efficient detection/delivery vehicle toward cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters D, Kastantin M, Kotamraju VR, Karmali PP, Gujraty K, Tirrell M, Ruoslahti E. Targeting atherosclerosis by using modular, multifunctional micelles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9815–9819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903369106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruenraroengsak P, Cook JM, Florence AT. Nanosystem drug targeting: Facing up to complex realities. J Control Release. 2010;141:265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabanov AV, Gendelman HE. Nanomedicine in the diagnosis and therapy of neuro degenerative disorders. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:1054–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sethuraman VA, Lee MC, Bae YH. A biodegradable pH-sensitive micelle system for targeting acidic solid tumors. Pharm Res. 2008;25:657–666. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim S, Kim JY, Huh KM, Acharya G, Park K. Hydrotropic polymer micelles containing acrylic acid moieties for oral delivery of paclitaxel. J Control Release. 2008;132:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen HT, Kim S, Li L, Wang S, Park K, Cheng JX. Release of hydrophobic molecules from polymer micelles into cell membranes revealed by Förster resonance energy transfer imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6596–6601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707046105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin HC, Alani AWG, Rao DA, Rockich NC, Kwon GS. Multi-drug loaded polymeric micelles for simultaneous delivery of poorly soluble anticancer drugs. J Control Release. 2009;140:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Wang YG, Chen XM, Wang JC, Zhang X, Zhang Q. NGR-modified micelles enhance their interaction with CD13-overexpressing tumor and endothelial cells. J Control Release. 2009;139:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang HJ, Xia HS, Wang J, Li YW. High intensity focused ultrasound-responsive release behavior of PLA-b-PEG copolymer micelles. J Control Release. 2009;139:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee ES, Gao ZG, Bae YH. Recent progress in tumor pH targeting nanotechnology. J Control Release. 2008;132:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim TY, Kim DW, Chung JY, Shin SG, Kim SC, Heo DS, Kim NK, Bang YJ. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of Genexol-PM, a Cremophor-free, polymeric micelle-formulated paclitaxel, in patients with advanced malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3708–3716. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamaguchi T, Matsumura Y, Suzuki M, Shimizu K, Goda R, Nakamura I, Nakatomi I, Yokoyama M, Kataoka K, Kakizoe T. NK105, a paclitaxel-incorporating micellar nanoparticle formulation, can extend in vivo antitumour activity and reduce the neurotoxicity of paclitaxel. Brit J Cancer. 2005;92:1240–1246. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchino H, Matsumura Y, Negishi T, Koizumi F, Hayashi T, Honda T, Nishiyama N, Kataoka K, Naito S, Kakizoe T. Cisplatin-incorporating polymeric micelles (NC-6004) can reduce nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity of cisplatin in rats. Brit J Cancer. 2005;93:678–687. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamaguchi T, Kato K, Yasui H, Morizane C, Ikeda M, Ueno H, Muro K, Yamada Y, Okusaka T, Shirao K, Shimada Y, Nakahama H, Matsumura Y. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of NK105, a paclitaxelincorporating micellar nanoparticle formulation. Brit J Cancer. 2007;97:170–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirao A, Hayashi M, Loykulnant S, Sugiyama K, Ryu SW, Haraguchi N, Matsuo A, Higashihara T. Precise syntheses of chain-multi-functionalized polymers, star-branched polymers, star-linear block polymers, densely branched polymers, and dendritic branched polymers based on iterative approach using functionalized 1,1-diphenylethylene derivatives. Prog Polym Sci. 2005;30:111–182. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harada A, Kataoka K. Supramolecular assemblies of block copolymers in aqueous media as nanocontainers relevant to biological applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2006;31:949–982. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee Y, Kataoka K. Biosignal-sensitive polyion complex micelles for the delivery of biopharmaceuticals. Soft Matter. 2009;5:3810–3817. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S, Kim JH, Jeon O, Kwon IC, Park K. Engineered polymers for advanced drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;71:420–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabanov AV, Vinogradov SV. Nanogels as pharmaceutical carriers: Finite networks of infinite capabilities. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:5418–5429. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis ME. Design and development of IT-101, a cyclodextrin-containing polymer conjugate of camptothecin. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:1189–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis ME. The first targeted delivery of siRNA in humans via a self-assembling, cyclodextrin polymer-based nanoparticle: From concept to clinic. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:659–668. doi: 10.1021/mp900015y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moon C, Kwon YM, Lee WK, Park YJ, Yang VC. In vitro assessment of a novel polyrotaxane-based drug delivery system integrated with a cell-penetrating peptide. J Control Release. 2007;124:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamashita A, Kanda D, Katoono R, Yui N, Ooya T, Maruyama A, Akita H, Kogure K, Harashima H. Supramolecular control of polyplex dissociation and cell transfection: Efficacy of amino groups and threading cyclodextrins in biocleavable polyrotaxanes. J Control Release. 2008;131:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Loh XJ. Cyclodextrin-based supramolecular architectures: Syntheses, structures, and applications for drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1000–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daly WH, Pochė D. The preparation of N-carboxyanhydrides of α-amino acids using bis(trichloromethyl) carbonate. Tetrahedron lett. 1988;29:5859–5862. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baussanne I, Benito JM, Mellet CO, Fernández JMG, Law H, Defaye J. Synthesis and comparative lectin-binding affinity of mannosyl-coated β-cyclodextrin-dendrimer constructs. Chem Commun. 2000:1489–1490. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harada A, Kataoka K. Formation of polyion complex micelles in an aqueous milieu from a pair of oppositely charged block copolymers with poly(ethylene glycol) segments. Macromolecules. 1995;28:5294–5299. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanayama N, Fukushima S, Nishiyama N, Itaka K, Jang WD, Miyata K, Yamasaki Y, Chung UI, Kataoka K. A PEG-based biocompatible block catiomer with high buffering capacity for the construction of polyplex micelles showing efficient gene transfer toward primary cells. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:439–444. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang JX, Ma PX. Polymeric core-shell assemblies mediated by host-guest interactions: Versatile nanocarriers for drug delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:964–968. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang JX, Qiu LY, Li XD, Jin Y, Zhu KJ. Versatile preparation of fluorescent particles based on polyphosphazenes: From micro- to nanoscale. Small. 2007;3:2081–2093. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki T. A nonlinear group contribution method for predicting the free energies of inclusion complexation of organic molecules with γ- and α-cyclodextrins. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2001;41:1266–1273. doi: 10.1021/ci010295f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yorozu T, Hoshino M, Imamura M. Fluorescence studies of pyrene inclusion complexes with α-, β-, and γ-cyclodextrins in aqueous solutions. Evidence for formation of pyrene dimer in γ-cyclodextrin cavity. J Phys Chem. 1982;86:4426–4429. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilhelm M, Zhao CL, Wang YC, Xu RL, Winnik MA, Mura JL, Riess G, Croucher MD. Polymer micelle formation.3. Poly(styrnen-ethylene oxide) block copolymer micelle formation in water- A fluorescence probe study. Macromolecules. 1991;24:1033–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eppell SJ, Zypman FR, Marchant RE. Probing the resolution limits and tip interactions of atomic force microscopy in the study of globular proteins. Langmuir. 1993;9:2281–2288. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyata K, Kakizawa Y, Nishiyama N, Yamasaki Y, Watanabe T, Kohara M, Kataoka K. Freeze-dried formulations for in vivo gene delivery of PEGylated polyplex micelles with disulfide crosslinked cores to the liver. J Control Release. 2005;109:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rekharsky MV, Inoue Y. Complexation thermodynamics of cyclodextrins. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1875–1917. doi: 10.1021/cr970015o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.