Abstract

A pre-post test, two-group study was conducted to examine the effects of a culturally competent targeted intervention titled GO EARLY Save Your Life on the breast cancer and early screening-related knowledge and beliefs and mammography use among 180 Korean American (KA) women aged 40 years or older who had not had mammograms within the past 12 months. The intervention group received an interactive education session focused on breast cancer, early screening guidelines, and beliefs (breast cancer-related and Korean cultural beliefs). The control group received no education. There was no statistically significant intervention effect on mammography use between the intervention (34%) and control groups (23%) at 24 weeks post baseline. The rates of mammography use for both groups significantly increased from 16 to 24 weeks post baseline. The education was effective in increasing breast cancer/early screening-related knowledge and modifying beliefs (decreasing barriers, fear, seriousness, and fatalism, and increasing preventive health orientation).

Keywords: Korean American, breast cancer, education, mammography use, culturally relevant

Introduction

The 1.3 million Koreans in the U.S. constitute 0.4% of the U.S. population. Among those, 75% are immigrants, 58% of those immigrants are females, and 42% of those females are aged 40 years or older (1). Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among Korean American (KA) women (2), and KA women are more prone to breast cancer than women in Korea (16.9 vs. 10.9 per 100,000) (3). The reasons for this are largely unknown, except for some evidence that risk for breast cancer among Asian women increases after at least 10 years of residing in the U.S. (4-5). KA women also present with larger (late-stage) tumor sizes (89%) than do Caucasian women (70%) (6). Those with a late-stage breast cancer diagnosis have a less favorable survival rate; promoting recommended screening mammography for early detection could offset this, leading to early-stage diagnosis (7).

KA women's screening mammography use, however, remains suboptimal: only 50%-59% of KA women had mammograms within the preceding 2 years; 33%-39% had a mammogram in the past year; and 65%-81% had at least one mammogram in the past (8-14). Thus, recommended annual mammography guidelines were not followed by most of these women. There is a need to provide culturally sensitive and theory-based mammography-promotion interventions for KA women who do not have screening mammograms as recommended.

Few studies have identified factors influencing KA women's adherence to recommended screening guidelines. Certain elements were significantly related to lower mammography use among KA women, such as certain demographic traits (older age, not being married, lower level of education, lower annual household income, lower English proficiency, lack of health insurance, and lack of routine check-ups), shorter length of U.S. residency, lack of physician recommendation for mammography use, and lack of knowledge related to breast cancer and recommended screening guidelines (10-23).

Although breast cancer-related health beliefs (perceived risk/susceptibility, seriousness, benefits, barriers, fear, and self-efficacy) played a significant role in mammography use among other ethnic subpopulations (24-32), studies have explored only a selected few of these correlates for mammography use specifically among KA women. Significantly associated with low rates of mammography use and/or adherence to recommended guidelines specifically among KA women were (1) high perception of barriers to having mammography (lack of time/family support/transportation, cost, knowledge deficit, fear, anxiety, and inconvenience in general); (2) low perception of benefits for mammography use (14, 22, 33-34); and (3) low perception of susceptibility to breast cancer (20, 33). Although fear and anxiety were identified as barriers for mammography use among KA women, the influence of such emotional/psychological correlates has not been explored fully. Women residing in Korea who were confident to follow through the steps for having a mammogram (self-efficacy) were more likely to intend to have a mammogram (35-36), but this factor has not been examined among KA women.

Cultural norms, values, and beliefs influence women's mammography use, but little is known about cultural beliefs' influence on mammography use among KA women. KAs are one of the most homogenous Asian American groups (1); thus, KA women often share common knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about promoting their well being. They tend to remain heavily attached to traditional Korean ways of thinking and lifestyle, which are often reinforced by their close ties with Korean friends, Korean neighbors, and Korean churches (37-40). They may have low levels of acculturation (language, social, and cultural assimilation) and may be less familiar with the health care system in the U.S. (39-40).

KA women's cultural values and beliefs stem from the traditional Korean health and illness concept (preventive health orientation), fatalistic view of life events (fatalism), and cultural norms for women (modesty), and these may greatly influence mammography use (11, 15, 21, 36, 40). In Korean traditional medicine, health and illness concepts are based on the yin-yang principles. The “yin” force of nature is the negative, dark, female force characterized by cold and emptiness, and the “yang” force is the positive, light, male force representing fullness and warmth. Various parts of the human body correspond to the principles of yin (e.g., inside) and yang (e.g., outside) forces (41). Koreans traditionally believe that problems in body and/or mind are not caused by clinically known factors for disease, but by an imbalance between positive and negative forces in the body from long-lasting anger, misconduct, negative thinking/attitude, or psychological stress. Thus, Koreans believe that each person is responsible for having a clean mind and body to maintain health and prevent diseases (including cancer) (42-43). Contrarily, under the Western belief of personal responsibility for one's own health and illness, a woman knows best about her own body and bodily function and when to seek medical assistance (44-45). Most Koreans lack preventive health orientation and do not engage in cancer prevention and/or early screening/detection practices because early screening is not considered part of maintaining a clean body and mind. Koreans are accustomed to taking health care-related action only when symptoms are present, or they delay seeking medical assistance until they cannot tolerate symptoms any longer (39, 46-47).

A fatalistic view of breast cancer has been found to be significantly associated with mammography use among other ethnic populations (48-51), and Korean women residing in Korea who perceived cancer as a fatalistic event were less likely to participate in early screening practice (35-36, 45). However, the association of fatalistic views of breast cancer and mammography use has not been explored for KA women. Koreans believe that mystical and supernatural powers are behind all events in daily life and that a person becomes ill from fate, devil's mischief, temporary separation of soul and body, misfortune, or past sins (42-43). Under this belief, most Koreans believe that if a woman gets breast cancer, it was meant to be and that is the way the woman is meant to die. Thus, most Korean women would not participate in breast cancer screening because early screening would not be perceived as able to prevent the woman from developing breast cancer; also, whether the woman finds out about having breast cancer in an early or later stage would not matter since she is meant to die from breast cancer as her predetermined fate regardless of the many different options for treatment (39, 46).

Among Koreans, it is considered a virtue for women to bear misfortunes, miseries, and unfair treatment silently and patiently. A woman does not act and achieve on her own, nor does she follow her own will. Suppression of emotional expression is also a virtue of women (52). Under this cultural norm, Korean women are socially prohibited from discussing bodily experiences (menstrual health, gastrointestinal ailments, breast-related health, or menopause) even among women. Consequently, women's health-related issues such as having screening mammography for early breast cancer detection tend to be regarded as trivial by not only women but also their family members (42, 53).

Regarding modesty, previous studies reported that KA women who were embarrassed and uncomfortable about their breasts being touched by a health care provider were less likely to obtain mammography (16, 20, 22-23, 33-34). Although embarrassment is an identified barrier for having a mammogram, none of the KA studies assessed broader aspects of modesty (shyness related to having mammography, having male health care providers, discussing sexuality and body parts with others) in relation to mammography use among KA women. Also, KA women who had a Korean physician had lower rates of breast cancer screening in the previous 2 years (57% mammography, 39% clinical breast examination) than did women who had a non-Korean physician (89% vs. 73%) (23).

The purpose of this study was to develop and test a theory-driven, culturally appropriate targeted intervention, titled GO EARLY Save Your Life, specifically focused on breast cancer and early screening knowledge and beliefs (breast cancer-related and Korean culture-related) to promote mammography use among KA women aged 40 years or older. In this study, we explored whether the educational intervention could modify breast cancer-related beliefs and Korean traditional cultural beliefs about breast cancer and early screening, in turn increasing mammography use among KA women.

Theoretical Framework

This study was guided by two integrated theoretical frameworks: the Transtheoretical Model of Change (TTM) and the Health Belief Model (HBM). The TTM emphasizes that having a mammogram usually occurs as a process or series of decisional changes related to women's readiness for mammography use. Each woman's changes of stage for readiness usually progress from not thinking about having a mammogram to thinking about having one to actually having a mammogram, based on her decisional balance for pros (benefits), cons (barriers), and self-efficacy of having a mammogram (54). The HBM theorizes that for a woman to have a mammogram, she must fulfill the following conditions: (1) have knowledge about breast cancer and early screening, (2) perceive she is susceptible to breast cancer, (3) perceive breast cancer is serious to her life, (4) perceive the positive outcomes associated with having a mammogram, (5) perceive few obstacles to having a mammogram (that are outweighed by benefits), and (6) feel confident in her ability to follow through necessary steps for having a mammogram (55). In addition to HBM belief constructs, the current study included Korean cultural beliefs (preventive health orientation, fatalistic view of breast cancer, and cultural norm of virtue of women) and acculturation. The combination of TTM and HBM provided the theoretical basis for the structure of the culturally competent educational contents and what correlates would theoretically predict the correlates of stages of mammography adoption among KA women.

Methods

Setting and Participants

This study used a two-group, quasi-experimental design with pre- and post-test measurements. Prior to study implementation, two KA churches in the Midwest were randomly assigned by coin toss to intervention or control condition. The churches were at least 30 miles away from each other and had fairly similar socioeconomic characteristics (number of congregation members, annual income, and length of U.S. residency). Church members would be considered as a representative group of KA women since the church is the primary social institution in addition to being a religious institution. KA women attend church services for cultivating fellowship and cultural ties; obtaining information, counseling, and advice on issues related to daily living in U.S.; sharing information with respect to matchmaking and business opportunities; and reinforcing their pre-immigrant social status and position among congregation members (Min, P.G. 1992. The structure and social functions of Korean immigrant churches in the United States. Internal Migration Review, 26, 1370-1394). Due to leadership and organizational changes in the intervention church, participant enrollment dropped considerably. In order to complete data collection, we added five more KA churches as intervention sites. The additional churches were geographically distant (at least 20 miles from each other), decreasing the potential for contamination. Therefore, a total of 7 churches (6 intervention churches and 1 control church) participated in this study. Because the churches were randomly assigned to either intervention or control conditions, women belonging to each church were automatically assigned to the study condition for that church (intervention or control group).

To assess changes in knowledge, beliefs, and mammography use pre- and post-GO EARLY, a minimum sample size of 80 per study group (N = 160) was required for 85% power based on an effect size of .25 at p < .05 (56). We recruited an additional 24 participants in anticipation of 15% attrition, based on two intervention studies with KA women (18, 22). However, we had only 4 women drop out of the study (2 women each from the intervention and control sites). A total of 180 KA women aged 40 years or older (90 women each in the intervention and control group) who had not had a mammogram in the past 12 months, did not have a personal history of breast cancer, and were able to speak/read/write Korean completed their participation in this study.

Participants were recruited from churches with flyers, word-of-mouth advertising, and announcements made at Sunday services. Each church had one community facilitator (CF) or contact person, a congregation member designated by the pastor to coordinate the necessary study procedures. The principal investigator (PI) and research assistant (RA) presented the study at the control and intervention sites during Sunday services. The PI presented the statistics for higher breast cancer incidence rates for KA women compared to women in Korea, and the rationale for the researchers to understand how to encourage Korean women to have breast cancer early screening as the announcement for study participants during the Sunday service. Participants who wanted more information were directed to a private room, where someone from the study team explained the study to them and answered questions. If the woman was willing to participate, she was asked to sign 2 copies of a Korean-language informed consent form that covered issues of voluntary participation and withdrawal, confidentiality, etc., as required by the institutional review board (IRB).

GO EARLY Save Your Life Intervention

The targeted interactive educational program was a 45-minute, semi-structured session offered to groups of 10-12 women. The educational content included breast cancer-related information (facts/figures, risk factors, treatment options, recommended early screening guidelines, and early screening rates for KA women); mammography-related beliefs (positive outcomes of regular mammography use, strategies to decrease barriers and increase confidence to follow through all steps of having a mammogram); and Korean cultural beliefs (issues related to preventive health orientation, fatalistic view of cancer, and cultural norms of women combined with watching KA women breast cancer survivor testimonial of having a screening mammogram). PowerPoint slides were used to illustrate certain points with culturally appropriate graphics and information. The interactive components of the intervention included women being asked for common barriers and cultural beliefs, and the PI discussing these with the group.

The educational content was translated into Korean and presented for an overall review of content and cultural relevance to two separate focus groups consisting of ten women aged 40-59 years and seven women aged 60 years and older from women's bible study or missionary groups at the control group site. These focus group participants usually attended the first Sunday service (early morning service) only due to their business hours (store/shop) for Sunday. Thus, they had almost no opportunity to meet with second Sunday service attendees who were in the control group for the study. Thus, there were no concerns about data contamination between the focus group and control group participants. The graphics, including font size, slide color, and pictures, were modified based on the focus group discussions prior to implementation. Although the intervention was qualitatively evaluated by the focus group at the control group site, the acceptability of the educational program was also assessed by a total of 90 participants at the intervention sites, utilizing a 12-item, 5-point Likert scale with statements (57). At the end of the education session, each woman completed the acceptability questionnaire. The mean score of overall acceptability was 3.6 (maximum score of 4). Cronbach's alpha was .95 for this scale.

Measurements

The questionnaire for this study incorporated items previously developed and shown to be (1) valid correlates predictive of mammography use based on the integrated theoretical framework, including breast cancer-related knowledge and beliefs (perceived risk, seriousness, benefits, barriers, fear, and self-efficacy), as well as (2) items relevant to traditional Korean cultural beliefs (preventive health orientation, fatalism, modesty) and acculturation. The original English-version questionnaire was translated into Korean by a modified committee translation method (58). The pilot study of the Korean-version questionnaire was conducted with 10 KA women 40 years or older at one intervention site. Women were asked to comment on the clarity, understandability, and readability of the Korean-language version questionnaire. No problematic sentence/wording was identified.

Demographic background

Demographic information included age, education, marital status, hours of work per week, annual household income, household size, length of U.S. residency, usual source of care (health insurance, family physician), personally known KA breast cancer survivor(s), and cancer screening practice(s) (BSE, CBE, and Pap smear).

Acculturation

Acculturation was measured by the Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIAS), a 16-item, multiple choice scale designed to assess the level of assimilation and self-identification of Asian populations (59). Cronbach's alpha was .86 for this study.

Breast cancer-related knowledge and beliefs

These concepts were assessed by the Champion Breast Cancer Survey (60-63). Champion's measure has been utilized previously for identifying factors affecting mammography use with Korean and/or Korean American women (11, 33-36). Knowledge related to breast cancer and early screening was assessed with multiple choices. Each correct response was given 1 point, and incorrect responses were given 0. The maximum score was 17 points. All belief subscales (risk, seriousness, benefits, barriers, fear, and self-efficacy) were rated on a 3-point Likert scale of whether respondents agree (3), are not sure (2), or disagree (1) with each statement. The KA pilot study group suggested using a short 3-point Likert scale. Higher numbers of points indicated higher agreement with each subscale's items. Certain items were reverse scored. Perceived risk was assessed with 5 statements (Cronbach's alpha in this study = .85); perceived seriousness was assessed with 8 statements (α = .70); perceived benefit was assessed with 5 statements (α = .55); perceived barriers were assessed with 17 statements (α = .79); perceived fear was assessed with 10 statements (α = .90); and perceived self-efficacy was assessed with 10 statements (α =.75).

For Korean traditional cultural beliefs related to breast cancer and early screening, perceived preventive health orientation was assessed with 11 statements regarding what behavior or attitudes KA women believed could maintain their health or protect themselves from illness, utilizing a subscale from the cultural barriers to breast cancer screening among Chinese American women (64). Cronbach's alpha was .72 for this study. Perceived fatalism was explored utilizing the Powe Fatalism Inventory (PFI), 15 statements with yes/no answer choices to assess beliefs that breast cancer is a pre-fixed life event beyond one's control and is a disease against which one is helpless (50). The PFI measures four distinct factors, including pessimism, inevitable death from breast cancer, pre-determinism, and fear. “Yes” responses had a value of 1, and “No” had a value of 0. A higher number of points indicated a higher perception of fatalism. Cronbach's alpha was .75 for this study. Perceived modesty was assessed with 7 statements regarding perceived subjective degree of shyness or shame in completing a mammogram, discussing sexuality, dealing with male health care providers, or discussing health problems with family/friends. Cronbach's alpha was .76 for this study.

Screening mammography status was assessed by self-reported mammography use at baseline and 2 additional follow-ups at 16 and 24 weeks post baseline.

Procedures

Women in the intervention group (N = 90) completed a pre-intervention questionnaire in person (baseline) and then attended a 45-minute educational session (10-12 women per session) conducted by the PI or a designated bilingual KA registered nurse health educator (HE) at the intervention church site. Women in the control group (N = 90) completed a questionnaire in person at the control church site (10-12 women per session to ensure an amenable environment for questionnaire completion). All study participants completed two follow-up questionnaires at 16 and 24 weeks post baseline. About four months after the completion of the data collection, women in the control group received the same educational contents as the intervention group, as requested by the participants.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics including means, frequencies, and standard deviations were employed to describe sociodemographic information, knowledge, and beliefs (perceived risk, seriousness, benefits, barriers, fear, self-efficacy, preventive health orientation, fatalism, and modesty). Differences in demographic characteristics between the two study groups were measured using Student's t test for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Changes in mammography use between pre- and post-intervention time periods were assessed using chi-square or Fisher's exact test. Factors amenable to change via the intervention were compared between pre- and post-intervention time periods using Student's t test and paired t test.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table I. There were mostly no significant demographic differences by groups. Mean age was 52.4 (SD 9.7), and women in the intervention groups (M = 56) were significantly older than women in the control group (M = 49) (t = -4.6, df = 178, p < .0001). There were no significant differences in acculturation level, marital status, education, and hours of work per week between groups. There were, however, significant differences in length of U.S. residency, annual household income, type of health insurance, and breast self-examination (BSE) performance. Significantly more women in the intervention group had resided in the U.S. longer than 10 years (χ2 = 24.7, df = 5, p < .001), had annual income of less than $10,000 (χ2 = 23.3, df = 4, p < .0001), and had smaller household size (χ2 = 9.6, df = 4, p < .05). There was no significant difference in whether women had health insurance or not, but significantly more women in the control group (54%) had private or HMO insurance (χ2 = 16.0, df = 3, p < .05) than women in intervention group (30%). Significantly more women in the control group (57%) had performed breast self-examination (BSE) (χ2 = 4.4, df = 1, p < .05) than women in the intervention group (41%).

Table I.

Demographics by Study Group Participants

| Total (N = 180) | Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 90) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 52.4 (9.7) | 55.6 (10.2) | 49.3 (8.0) | < .0001 |

| Acculturation, mean (SD) | 28.3 (5.4) | 28.3 (5.3) | 28.3 (5.3) | NS |

| Marital status (%) | NS | |||

| Married | 82 | 77 | 87 | |

| Not Married | 16 | 20 | 11 | |

| Never married | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| Education (%) | NS | |||

| Less than HS | 7 | 9 | 3 | |

| High school | 26 | 29 | 22 | |

| Some college | 54 | 51 | 58 | |

| College/Higher | 13 | 10 | 17 | |

| Years in U.S. (%) | < .001 | |||

| ≤ 10 yrs | 28 | 18 | 36 | |

| > 10 yrs | 72 | 82 | 64 | |

| Working Hours (%) | NS | |||

| 40+ hrs/week | 48 | 48 | 49 | |

| < 40 hrs/week | 28 | 24 | 31 | |

| Retired | 11 | 16 | 6 | |

| Never worked | 13 | 12 | 14 | |

| Household size (%) | < .05 | |||

| 1-2 | 29 | 38 | 21 | |

| 3 + | 71 | 63 | 80 | |

| Annual Income (%) | < .0001 | |||

| < $10,000 | 9 | 17 | 2 | |

| $10,000-$39,999 | 29 | 37 | 20 | |

| $40,000-$54,999 | 18 | 13 | 23 | |

| > $55,000 | 43 | 32 | 54 | |

| Insurance (Yes, %) | 57 | 54 | 60 | NS |

| Type of insurance (%) | < .05 | |||

| Private/HMO | 85 | 72 | 98 | |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 15 | 28 | 2 | |

| Primary Care | NS | |||

| Provider (Yes, %) | 68 | 70 | 66 | |

| KA physician | 80 | 86 | 73 | |

| Non-Korean | 20 | 14 | 27 | |

| Know someone with breast cancer (%) | 56 | 56 | 56 | NS |

| Family member has breast cancer (%) | 12 | 16 | 9 | NS |

| Ever had CBE (%) | 75 | 71 | 79 | NS |

| Ever had Pap smear (%) | 75 | 74 | 76 | NS |

| Perform BSE (%) | 49 | 41 | 57 | < .05 |

| Every now and then | 90 | 87 | 92 | |

| Ever had breast problem (%) | 6 | 8 | 3 | NS |

t test for continuous variables, chi-square or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables.

CBE (clinical breast examination), BSE (breast self-examination), NS (not significant).

Mammography Status

There were no significant differences in mammography use between groups at baseline. At baseline, 70% (n = 63) of women in the intervention group and 71% (n = 64) in the control group had mammograms in the past (more than 12 months ago). There were no statistically significant differences in mammography use between groups post test. At 16 weeks post test, 19% (n = 17) of women in the intervention group and 16% (n = 14) in the control group had mammograms. At 24 weeks post test, 34% (n = 31) of women in the intervention group and 23% (n = 21) in the control group had mammograms. There were statistically significant increases in mammography use between 16 and 24 weeks within each group. Screening mammography use increased by 15% (n = 14) for the intervention group (p < .001) and 7% (n = 7) for the control group (p < .05). These increases were not statistically significant between groups (Table II).

Table II.

Post-Intervention Mammogram Screening by Study Groups (N = 180)

| Mammogram Screening (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 90) | pa | |

| Baseline | 70% (n = 63) | 71% (n = 64) | NS |

| 16 Weeks Post-test | 19% (n = 17) | 16% (n = 14) | NS |

| 24 Weeks Post-test | 34% (n = 31) | 23% (n = 21) | NS |

| p value (16 vs. 24 weeks)b | < 0.001 | < 0.05 | |

chi-square or Fisher's exact test

McNemar test

NS (not significant)

Differences in Knowledge and Beliefs

We conducted Student's t tests to assess mean score differences in knowledge and beliefs (perceived risk, benefits, barriers, seriousness, fear, self-efficacy, preventive health orientation, fatalism, and modesty) for pre- and post-test measurement time periods for the two groups (Table III). There were significant mean score differences in knowledge, perceived barriers, self-confidence, fatalism, and preventive health orientation. Women in the intervention group had significantly higher: knowledge scores at 16 weeks (t = -2.9, df = 178, p < .05) and 24 weeks (t = -4.0, df = 178, p < .0001), and self-efficacy scores at 16 weeks (t = -.2.0, df = 178, p < .05). Women in the intervention group also had significantly lower: barrier scores at 16 weeks (t = 2.7, df = 178, p < .05) and 24 weeks (t = 2.2, df = 178, p < .05), fatalism scores at 16 weeks (t = 2.4, df = 178, p < .05), and lower preventive health orientation scores at 24 weeks (t = 2.5, df = 178, p < .05).

Table III.

Differences in Mean Scores for Knowledge and Beliefs by Study Groups (N = 180)

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 90) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||

| Baseline | 8.5 (3.0) | 8.3 (2.5) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 9.6 (2.6) | 8.5 (2.3) | < .05 |

| 24 weeks | 9.5 (2.3) | 8.1 (2.4) | < .0001 |

| Barriers | |||

| Baseline | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.4) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.4) | < .05 |

| 24 weeks | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.3) | < .05 |

| Self-efficacy | |||

| Baseline | 2.7 (0.3) | 2.7 (0.3) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 2.8 (0.3) | 2.7 (0.4) | < .05 |

| 24 weeks | 2.7 (0.4) | 2.6 (0.4) | NS |

| Preventive Health Orientation | |||

| Baseline | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.4) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.4) | NS |

| 24 weeks | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.4) | < .05 |

| Fatalism | |||

| Baseline | 1.2 (1.7) | 1.5 (2.2) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 0.7 (1.3) | 1.3 (2.3) | < .05 |

| 24 weeks | 0.8 (2.1) | 1.2 (2.1) | NS |

| Susceptibility | |||

| Baseline | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) | NS |

| 24 weeks | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.4) | NS |

| Benefits | |||

| Baseline | 2.8 (0.3) | 2.9 (0.2) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 2.9 (0.2) | 2.8 (0.3) | NS |

| 24 weeks | 2.8 (0.4) | 2.9 (0.3) | NS |

| Fear | |||

| Baseline | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.6) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 1.5 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.4) | NS |

| 24 weeks | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.4) | NS |

| Seriousness | |||

| Baseline | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.4) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.4) | NS |

| 24 weeks | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.4) | NS |

| Modesty | |||

| Baseline | 1.8 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.6) | NS |

| 16 weeks | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.5) | NS |

| 24 weeks | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.5) | NS |

t test, NS (not significant).

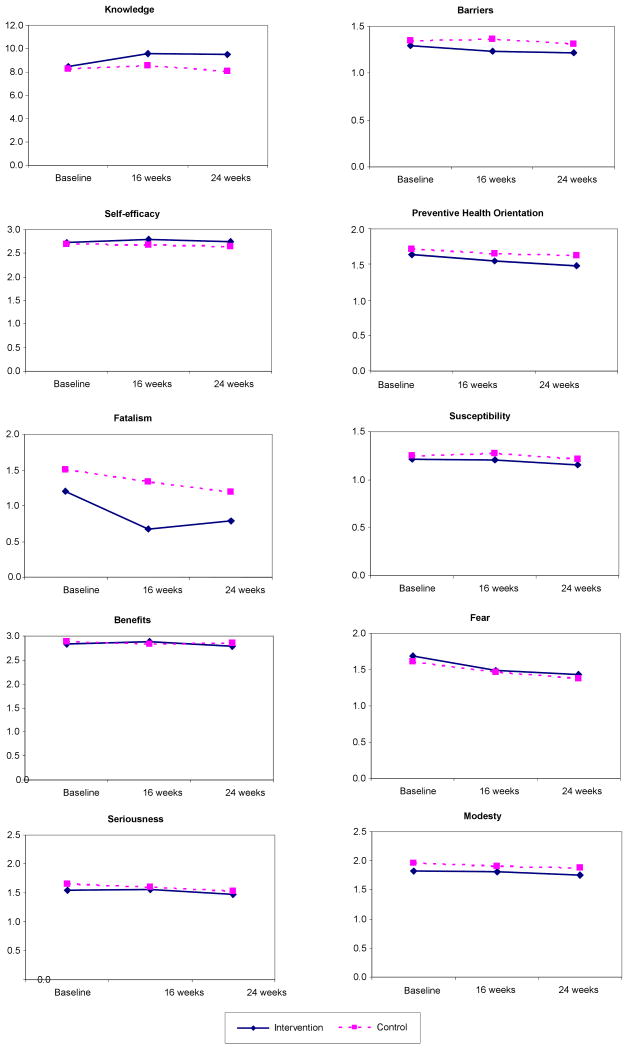

Changes in Knowledge and Beliefs between Pre and Post Test by Groups

We conducted paired t tests to assess changes in knowledge and beliefs between pre- and post-test measurement time periods by groups (Figure 1). For the intervention group, significant changes were seen from pre to post test in knowledge and perceived benefits (both increased) and perceived barriers, fear, seriousness, fatalism, and traditional Korean preventive health orientation (all decreased). For the control group, significant changes were seen from pre to post test in perceived fear, seriousness, and traditional Korean preventive health orientation (all decreased). Scores did differ between 16 and 24 weeks (Figure 1). Significant changes from 16 to 24 weeks were seen in the intervention group for knowledge, perceived benefits, barriers, fear, seriousness, fatalism, and traditional Korean preventive health orientation. In the control group, significant changes from 16 to 24 weeks were seen for perceived fear, seriousness, and traditional Korean preventive health orientation. The significant changes at the three time points are illustrated in Figure 1 and discussed further in the “Discussion” section below.

Figure 1.

Changes in Knowledge and Beliefs between Pre and Post Test by Study Groups

Discussion

This study examined the impact of a culturally appropriate educational program (GO EARLY Save Your Life) on knowledge, beliefs (breast cancer and traditional Korean cultural beliefs), and mammography use among KA women. There were no statistically significant differences in mammography use between the intervention and control groups (34% vs. 23%) at 24 weeks post test. However, 34% (n = 31) of women obtained mammograms within 6 months of their participation in the educational session, which is clinically significant considering KA women had the lowest mammography rates (33%-39% had mammograms in the past 12 months) among ethnic subpopulations in the U.S. (8-14). Twenty-three percent (n = 21) of women in the control group obtained mammograms within 24 weeks post baseline questionnaire completion, suggesting that the repeated completion of questionnaires alone might play a role of a “minimal intervention” as a cue to action to think about or remind KA women to have breast cancer early screening. In addition, although it was not feasible for the current study, future studies could assess whether improvement in screening mammography use within 6 months is attributed to receiving mammography education through this project and/or some confounding factor (i.e., participating in another educational program or project). We did not ask specifically whether they had heard about mammography prior to participation in this study, and we were not aware of any other community-based mammography educational program for KA women while this study was in progress. Also not feasible in this pilot study was verification of self-reported used of mammograms with medical record data. Such verification in future studies could strengthen the validity of the outcome measure.

Both groups showed significant increases in mammography use between the two post-test time periods (16 to 24 weeks). Mammography use rates in the intervention group increased from 19% to 34% and in the control group from 16% to 23%. Although these increases were not statistically significant between groups, the 15% margin of change for women who had received the education is notable for an 8-week time period when compared to the 7% increase for women who had not received the education. These findings suggest that we may be able to further evaluate the effectiveness of the GO EARLY Save Your Life educational program with more repeated measures (i.e., 36 weeks and 48 weeks post test). Since most KA women in this study were working 40 hours or more per week (as the demographics indicated), they might need more than 6 months to make the necessary arrangements (schedule change for daily activities, transportation, child care, etc.) for a mammogram; they also might not consider having a mammogram as a priority for them under the traditional Korean cultural view of women's role as caretaker for family members (husband, children, in-laws) (42, 52-53). In addition, considering KA women's busy lives in general, a one-time, short educational intervention may not be sufficient for KA women to change their preventive health behavior (such as having a screening mammogram within 6 months post education). Thus, a booster educational session would be another intervention method to promote mammography use among KA women. This booster dose of education could be a tailored intervention (i.e., tailored message or community-based individual navigator program) focusing on each woman's unique barriers. Such an intervention, if successful, may also serve to impact repeat screening.

The educational program was effective in modifying the knowledge and beliefs for KA women in this study, and these findings are supported by other studies (10-11, 13, 15, 18, 21). KA women who received the education intervention had significantly higher knowledge scores related to breast cancer and recommended early screening guidelines than did women who had not received the education, and the women who received the education intervention retained their higher level of knowledge at 6 months post-education. Women who had received the education had significantly lower perceptions of barriers for having a mammogram, and they perceived higher self-confidence for having a mammogram. These findings indicate that the educational content was culturally relevant and effective in decreasing or minimizing the perceived barriers, which in turn may have increased self-confidence for KA women in this study.

Perceived seriousness significantly decreased for both groups from pre to post test. Women who received the education session had lower perceived seriousness at 16 and 24 weeks, while women who did not receive the education had lower perceived seriousness only at 24 weeks. However, perceived negative consequences were also lower in the control group. This might be explained by many factors. The questionnaire might have acted as a cue to seeking information. Since women in the control group reported higher education, they may have sought information on their own. Control group women also reported higher income and younger age, both of which are known to be associated with increased mammogram use. This may have contributed to increased screening in the control group, negating intervention effect. Future studies with community-based samples should focus on group equivalence between study sites. This possibility might also explain the decrease in perceived fear at both post-test time periods.

Perceived fatalism significantly decreased among women who received the education, as did Korean traditional preventive health orientation. The findings suggest that the Korean traditional fatalistic view of breast cancer and preventive health orientation can be modified through culturally appropriate educational contents such as GO EARLY Save Your Life in this study; these findings are supported by other studies (10, 18).

One limitation of this study is generalizability, as the findings of this study may not be generalized to KA women residing in other areas of the city and/or U.S. The study was conducted with residents of suburban areas. KA women residing in metropolitan areas might have different results. A longitudinal study with more repeated outcome measures is needed to evaluate further the effects of the educational program on mammography status. However, simply adding data points may not be sufficient; other limitations of this study such as lack of sample equivalence should also be addressed. A replicated study with KA women residing in other areas would be helpful to assess feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of the educational program for promoting mammography use. In addition, we acknowledge that multiple testing may inflate type I error. However, correction of multiple testing remains controversial. It has been shown that a correction for multiple testing can create more problems than it solves: namely, the universal null hypothesis is of little interest, the exact number of investigations to be adjusted for cannot be determined, and the probability of type II error increases, leading to the recommendation by some experts that routine correction of multiple testing is not necessary (65-66). A better solution would be to construct a composite endpoint of all of the study variables and subsequently to perform a statistical analysis on the composite endpoint only, which we plan to develop and analyze in a separate measurement paper.

Conclusion/Nursing Implication

This was the first study to test a targeted breast cancer screening intervention specifically designed to promote mammography use among KA women by manipulating knowledge and beliefs (related to breast cancer and Korean traditional cultural beliefs) based on integrated theoretical frameworks (TTM and HBM). The GO EARLY Save Your Life intervention was feasible and culturally sensitive to KA women, and can be replicated in various KA communities. The education was effective in increasing breast cancer/early screening-related knowledge and beliefs (barriers, fear, seriousness, fatalism, and preventive health orientation).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (#5 R21 NR009854-02). The authors gratefully acknowledge editorial assistance from Kevin Grandfield.

References

- 1.U.S. Bureau of Census. Selected population profile in the U.S. American Community Survey. [3/11/2008];2006 http://factfinder.census.org.

- 2.McCracken M, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2007;57(4):190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez S, et al. Cancer incidence patterns in Koreans in the US and in Kangwha, South Korea. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14(2):167–174. doi: 10.1023/a:1023046121214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deapen D, et al. Rapidly rising breast cancer incidence rates among Asian-American women. Internal Journal of Cancer. 2002;99(5):747–750. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziegler RG, et al. Migration pattern and breast cancer risk in Asian-American women. Journal of Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(22):1819–1827. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.22.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedeen AN, White E, Taylor V. Ethnicity and birthplace in relation to tumor size and stage in Asian American women with breast cancer. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(8):1248–1252. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Facts & Figures 2008. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: Georgia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Breast- and cervical-cancer screening among Korean women-Santa Clara County, California, 1994 and 2002. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53(33):765–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kandula NR, et al. Low rates of colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in Asian Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites: Cultural influences or access to care? Cancer. 2006;107(1):184–192. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Menon U. Pre and Post intervention differences in acculturation, knowledge, beliefs, and stages of readiness to have screening mammograms among Korean American women. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2008 doi: 10.1188/09.onf.e80-e92. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee EE, Fogg LF, Sadler GR. Factors of breast cancer screening among Korean immigrants in the United States. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2006;8(3):223–233. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9326-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swan J, et al. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States. Results from the 2000 National Health Interview Study. Cancer. 2003;97:1528–1540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarna L, et al. Cancer screening among Korean-Americans. Cancer Practice. 2001;9(3):134–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009003134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juon HS, et al. Predictors of adherence to screening mammography among Korean American women. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39(3):474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juon HS, Seo YJ, Kim MT. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Korean American elderly women. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2002;6(4):228–235. doi: 10.1054/ejon.2002.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juon HS, Choi Y, Kim MT. Cancer screening behaviors among Korean-American women. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2000;24(6):589–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juon HS, et al. Impact of breast cancer screening intervention on Korean-American women in Maryland. Cancer Detection & Prevention. 2006;30(3):297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YH, Sarna L. An intervention to increase mammography use by Korean American women. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2004;31(1):105–110. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Warda US. Mammography utilization and related attitudes among Korean-American women. Women's Health. 1998;27(3):89–107. doi: 10.1300/J013v27n03_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Warda US. Demographic predictors of cancer screening among Filipino and Korean immigrants in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18(1):62–68. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moskowitz JM, et al. “Health is strength”: A community health education program to improve breast and cervical cancer screening among Korean American women in Alameda County, California. Cancer Detection & Prevention. 2007;31:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadler GR, et al. Korean women: breast cancer knowledge, attitudes and behaviors. BMC Public Health. 2001;1(1):7–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lew AA, et al. Effects of provider status on preventive screening among Korean-American women in Alameda County, California. Preventive Medicine. 2003;36(2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abbaszadeh A, et al. The relationship between women's health beliefs and their participation in screening mammography. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2007;8(4):471–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell KM, et al. Sociocultural context of mammography screening use. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006;33(1):105–112. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garza MA, et al. A culturally targeted intervention to promote breast cancer screening among low-income women in East Baltimore, Maryland. Cancer Control. 2005;12(S 2):34–41. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004S06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu MY, Wu TY. Factors influencing mammography screening of Chinese American women. Journal of Obstetrics Gynecological & Neonatal Nursing. 2005;34(3):386–394. doi: 10.1177/0884217505276256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Champion, et al. Measuring mammography and breast cancer beliefs in African American women. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(6):827–837. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menon U, et al. Health belief model variables as predictors of progression in stage of mammography adoption. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2007;21(4):255–261. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.4.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee-Lin, et al. Breast cancer beliefs and mammography screening practices among Chinese American immigrants. Journal of Obstetrics Gynecological & Neonatal Nursing. 2007;36(3):212–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consedine NS, et al. The contribution of emotional characteristics to breast cancer screening among women from six ethnic groups. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38(1):64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Champion VL, et al. A breast cancer fear scale: psychometric development. Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9(6):753–762. doi: 10.1177/1359105304045383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han Y, William RD, Harrison RA. Breast cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Korean American women. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2000;27(10):1585–1591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu MY, Hong OS, Seetoo AD. Uncovering factors contributing to under-utilization of breast cancer screening by Chinese and Korean women living in the United States. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13(2):213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ham OK. The intention of future mammography screening among Korean women. J Community Health Nursing. 2005;22(1):1–13. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2201_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ham OK. Factors affecting mammography behavior and intention among Korean women. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006;33(1):113–119. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurh WM, Kim KC. Korean immigrants in America. New Jersey: Associated University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Min PG. The structure and social functions of Korean immigrant churches in the United States. International Migration Review. 1992;26(2):1370–1394. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SK, et al. Acculturation and health in Korean Americans. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51(2):159–173. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin HS, et al. Patterns and factors associated with health care utilization among Korean American elderly. Asian American and Pacific Islander Journal of Health. 2000;8:117–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hong MH. Dongeuibogam. Seoul, Korea: Dunggi; 1990. Heo Jun. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim KI. Traditional attitudes on illness in Korea. Modern Medicine. 1972;15(1):49–51. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kendall L. Healing thyself: A Korean shaman's afflictions. Social Science & Medicine. 1988;27(5):445–450. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Im EO, et al. Korean women's breast cancer experience. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;24:751–765. doi: 10.1177/019394502762476960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Im EO, et al. Korean women's attitudes toward breast cancer screening tests. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2004;41:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sohn L, Harada ND. Knowledge and use of preventive health practices among Korean women in Los Angeles County. Preventive Medicine. 2005;41(1):167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang SJ, et al. Older Korean people's desire to participate in health care decision making. Nursing Ethics. 2008;15(1):73–86. doi: 10.1177/0969733007083936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mayo RM, et al. Importance of fatalism in understanding mammography screening in rural elderly women. Journal of Women & Aging. 2001;13(1):57–72. doi: 10.1300/J074v13n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips JM, et al. Breast cancer screening and African American women: fear, fatalism, and silence. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1999;26(3):561–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Powe BD. Cancer fatalism among elderly Caucasians and African Americans. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1995;22(9):1355–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Powe BD, et al. Perceptions of cancer fatalism and cancer knowledge: a comparison of older and younger African American women. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2006;24(4):1–13. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang Y. Women in a Confucian society: The case of Chosun Dynasty Korea (1392-1910) In: Yu EY, Phillips EH, editors. Traditional thoughts and practices in Korea. Los Angeles: Center for Korean-American & Korean Studies; 1983. pp. 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park S. Rural Korean housewives' attitudes toward illness. Yonsei Medical Journal. 1987;28(2):105–111. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1987.28.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997;12(1):38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stretcher VJ, Rosenstock IM. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education; Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fay MP, et al. Accounting for variability in sample size estimation with applications to non-adherence and estimation of variance and effect size. Biometrics. 2007;63(2):465–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilkie DJ, et al. Cancer symptom control: feasibility of a tailored, interactive computerized program for patients. Family Community Health. 2001;24(3):48–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prieto A. A method for translation of instruments to other language. Adult Education Quarterly. 1992;43(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suinn RM, et al. The Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation scale: cross-cultural information. Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development. 1995;23(3):139–148. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Champion VL, Menon U. Predicting mammography and breast self-examination in African American women. Cancer Nursing. 1997;20(5):315–322. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Champion VL, Scott CR. Reliability and validity of breast cancer screening belief scales in African American women. Nursing Research. 1997;46(6):331–337. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Champion VL. Revised susceptibility, pros, and cons scale for mammography screening. Research in Nursing & Health. 1999;22(4):341–348. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199908)22:4<341::aid-nur8>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Champion VL, et al. Comparisons of tailored mammography interventions at two months post-intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24(3):211–218. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang TS, et al. Cultural cons to mammography, clinical breast examination, and breast self examination among Chinese-American women 60 and older. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:575–583. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cleophas TJ, Zwinderman AH. Clinical trials are often false positive: A review of simple methods to control this problem. Current Clinical Pharmacology. 2006;1:1–4. doi: 10.2174/157488406775268228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balázs G, et al. The problem of multiple testing and solutions for genome-wide studies. Orvosi Hetilap. 2005;146(12):559–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]