Abstract

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) mediates reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), wherein excess cholesterol is conveyed from peripheral tissues to the liver and steroidogenic organs. During this process HDL continually transitions between subclass sizes, each with unique biological activities. For instance, RCT is initiated by the interaction of lipid-free/lipid-poor apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) with ABCA1, a membrane-associated lipid transporter, to form nascent HDL. Because nearly all circulating apoA-I is lipid-bound, the source of lipid-free/lipid-poor apoA-I is unclear. Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) then drives the conversion of nascent HDL to spherical HDL by catalyzing cholesterol esterification, an essential step in RCT. To investigate the relationship between HDL particle size and events critical to RCT such as LCAT activation and lipid-free apoA-I production for ABCA1 interaction, we reconstituted five subclasses of HDL particles (rHDL of 7.8, 8.4, 9.6, 12.2, and 17.0 nm in diameter, respectively) using various molar ratios of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, free cholesterol, and apoA-I. Kinetic analyses of this comprehensive array of rHDL particles suggest that apoA-I stoichiometry in rHDL is a critical factor governing LCAT activation. Electron microscopy revealed specific morphological differences in the HDL subclasses that may affect functionality. Furthermore, stability measurements demonstrated that the previously uncharacterized 8.4 nm rHDL particles rapidly convert to 7.8 nm particles, concomitant with the dissociation of lipid-free/lipid-poor apoA-I. Thus, lipid-free/lipid-poor apoA-I generated by the remodeling of HDL may be an essential intermediate in RCT and HDL’s in vivo maturation.

The antiatherogenic properties of high-density lipoprotein (HDL)1 have been ascribed in part to its role in reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) (1–3). In this process, HDL mobilizes excess free cholesterol and other lipids from peripheral tissues and delivers them to the liver and steroidogenic organs. Apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), the major HDL protein and primary determinant of HDL structure, plays a key role in RCT in part by activating lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (4) (LCAT). LCAT converts free unesterified cholesterol (FC) to cholesteryl ester (CE), promoting the transfer of cholesterol from the surface to the core of the HDL particle. ApoA-I plays additional important roles in RCT, including stimulation of cholesterol efflux from cells through its interaction with the ATP binding cassette transporter A-1 (ABCA1) (5, 6).

ApoA-I is one of a dozen known exchangeable apolipoproteins in humans (7), with the ability to adapt conformationally to changes in lipid environment, which is central to HDL function. This adaptive ability is manifested in the biogenesis and metabolic cycle of HDL, wherein the HDL particle undergoes a transition from a FC-rich discoidal form to a CE-laden spherical particle. This transition is a key event in RCT and is critical to HDL’s antiatherosclerotic properties.

The conformational adaptations apoA-I undergoes in response to changes in HDL particle size and lipid cargo contribute significantly to the binding properties of HDL with cellular receptors, enzymes, and transporters (8). For example, lipid-free/lipid-poor apoA-I is the primary ligand for ABCA1 (2), whereas discoidal HDL is better at supporting LCAT activity than either lipid-free or spherical HDL. Furthermore, spherical HDL is the preferred substrate for scavenger receptor B type I (SR-BI) (9). While much of RCT is understood, the mechanisms underlying certain critical steps in this pathway remain to be elucidated. For example, the vast majority of apoA-I in vivo is lipid bound (10), and the source of lipid-free/lipid-poor apoA-I needed for interaction with ABCA1 is unknown.

Reconstituted HDL (rHDL) have been widely used to investigate how apoA-I conformation influences HDL formation and biological activity, and rHDL particles of defined size and lipid/protein composition can be generated by combining apoA-I with physiological lipids such as 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and cholesterol at specific molar ratios (11–13). This approach yields populations of particles with a distinct range of sizes, suggesting that apoA-I is capable of a limited repertoire of conformational adaptations.

The phospholipids employed to reconstitute HDL also contribute to the size and the stability of the particles. For example, 1,2-dmiyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) and apoA-I preferentially generate five classes of particles containing two apoA-I molecules, termed R2-1 to R2-5, that are characterized by increasing Stokes’ diameter (14). By this nomenclature, the smallest particle (R2-1) has a diameter of 9.8 nm and the largest (R2-5) 12.0 nm. POPC produces rHDL subclasses of slightly different sizes, including a smaller particle of 7.8 nm called R2-0 (13). These observations emphasize the role of lipid composition in dictating the sizes of rHDL particles produced at different lipid to protein ratios. However, various other factors, including temperature and length of incubation, may affect particle size and stability. Despite these many parameters, it is possible to reproducibly isolate well-defined size classes of rHDL when the temperature of incubation and dialysis, incubation times, and molar ratios of phospholipid:protein:deoxycholate are carefully controlled.

When HDL is reconstituted at POPC:apoA-I molar ratios of 80:1, the main product is a 9.6 nm particle, but an additional 8.6 nm diameter species is also observed (15, 16). The appearance of an “intermediate” 8.7 nm particle has been observed when 9.6 nm disks were incubated with LDL and remodeled toward smaller species, mainly 7.8 nm particles (17,18). Recent studies have demonstrated that a 8.5 nm nascent HDL species is generated by an ABCAl-dependent pathway when mouse macrophages are exposed to lipid-free human plasma apoA-I (19). Despite this and other evidence (20, 21) of the presence of ∼8.4 nm particles in reconstituted HDL preparations and in in vivo samples, no published studies describe the reconstitution, isolation, and characterization of POPC rHDL particles of size between 9.6 and 7.8 nm in diameter. Thus, little is known about the properties of this rHDL subclass.

The LCAT activation properties of rHDL subclasses have been extensively studied (16, 22–28), but the relative LCAT activation efficiencies of rHDL subclasses containing two apoA-I molecules versus rHDL containing more than two apoA-I molecules have not been systematically evaluated. For rHDL containing two molecules of apoA-I, 9.6 nm particles have been consistently reported as the best LCAT activator. In one study, larger species (13.4 and 17.0 nm diameter rHDL) containing more than two apoA-I molecules were better LCAT activators than 9.6 nm particles (29). The structural basis for these differences remains poorly understood but may provide insight into the mechanism underlying HDL’s subclass-specific LCAT activation.

In this study, we employed a POPC/apoA-I-based reconstitution protocol and a novel isolation procedure to produce the first comprehensive array of purified rHDL particles, including the previously uncharacterized 8.4 nm particle. rHDL particles of 7.8, 8.4, 9.6, 12.2, and 17.0 nm diameters were evaluated for relative stability, apoA-I stoichiometry, and ability to support LCAT activity. Our results indicate that there is a direct relationship between HDL size, apoA-I content, and LCAT activation, that different subclasses of particles have distinct morphology and stability, and that spontaneous remodeling of HDL particles represents a potential mechanism for the generation of lipid-free/lipid-poor apoA-I in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL); sodium deoxycholate and cholesterol were from Sigma-Aldrich. Protease inhibitor cocktail set III was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Human LCAT purified from plasma was provided by Dr. John Parks (Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC).

Production of Recombinant ApoA-I Protein

Human apoA-I was expressed in Escherichia coli (E. coli) using the pET-20b bacterial expression vector (Novagen, Inc., Madison, WI), as described (30). Briefly, the pNFXex plasmid was transformed into the E. coli strain BL21(DE-3) pLysS, and protein expression was carried out as described by the manufacturer in NZCYM media containing 50 µg/mL ampicillin. Expressed proteins were purified via Hi-Trap nickel chelating columns (GE Healthcare, Inc., Piscataway, NJ) as described (31). The pooled eluted protein was dialyzed extensively against Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 8.2 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4), supplemented with 1 mM benzamidine. Protease inhibitor cocktail set III was added, diluting 200-fold the stock solution, and the protein was filter (MCE, 0.2 µm; Fisher Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL) sterilized.

Preparation of ApoA-I–POPC Complexes

rHDL were prepared by a modification (11) of the sodium cholate dialysis method originally described by Matz et al. (12). Different particle size subclasses were obtained as described by Maiorano et al. (32). Briefly, POPC and FC were dissolved in chloroform–methanol (3:1 v/v) and dried under a N2 stream, and the residual solvent was removed by overnight lyophilization. The dried mixture was preincubated at 37 °C in TBS, pH 8.0, in the presence of 19 mM sodium deoxycholate (DC) and vortexed, and the incubation was extended until clear. ApoA-I was then added to the POPC/ FC solution to final molar ratios of POPC:FC:apoA-I equal to 30:2:1 for selecting <9.6 nm rHDL disks, 80:4:1 for reconstituting predominantly 9.6 nm disks, and 160:8:1 for selecting >9.6 nm rHDL disks. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C and the deoxycholate removed by 3 days dialysis against TBS, pH 8.0, at 4 °C with three changes.

Isolation of rHDL Subclasses

Lipidation mixtures were first purified of any unreacted protein and residual vesicular structures by discontinuous gradient density ultracentrifugation. Briefly, each lipidation mixture was adjusted to a volume of 1.5 mL by TBS and gently added to a 1.5 mL layer of KBr (0.33 mg/mL). The samples were spun for 3 h at 65000 rpm on a Beckmann Optima TL ultracentrifuge at 4 °C, and 300 µL fractions were collected from top to bottom. The fractions were analyzed for protein and phospholipid content. Fractions containing both proteins and lipids, assumed to represent reconstituted lipoprotein particles, were pooled together and further purified by size exclusion chromatography. Reconstituted HDL particles of different size were separated on a Superdex 200 prep grade XK 16/100 column (GE Biosciences Inc., Piscataway, NJ), run at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min in TBS, pH 8.0 (Figure 3). Fractions were analyzed on 4–20% gels as described below. The fractions corresponding to rHDL particle subclasses were concentrated using Vivaspin-6 10000 MWCO ultrafiltration devices (Sartorius Biotech Inc., Edgewood, NY) before further analysis. No differences in rHDL particle size were detectable by NDGGE before and after spin concentration up to a concentration factor of 15 (from 0.1 to 1.5 mg/mL in protein concentration).

FIGURE 3.

Panel A: Elution profile of size exclusion chromatography purification of a 30:2:1 POPC:FC:apoA-I lipidation mixture. Panel B: NDGGE analysis of the mixture prior to column separation (lane 2) and elution fractions (lanes 4–7). Lanes 5 and 7 show pure 8.4 and 7.8 nm rHDL particles, respectively. Lanes 1 and 3: Molecular weight markers.

rHDL Particle Characterization

Phospholipid and protein assays were performed to determine the final composition of the rHDL complexes. Protein concentration was assayed by the MicroBCA assay kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. The concentration of POPC was measured by the phospholipids B kit from Wako Chemicals GmbH (Neuss, Germany) and reconfirmed by the Fiske-SubbaRow assay (33). Cholesterol concentration was obtained by enzymatic assay using the cholesterol E kit from Wako Chemicals GmbH (Neuss, Germany). Residual DC was measured semiquantitatively by mass spectrometry (MS). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight MS (MALDI-TOF-MS) was performed using a Voyager-DE STR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Using a known amount of DC as external standard, MS analysis confirmed that there were no rHDL size-specific differences in residual DC (data not shown).

The hydrodynamic Stokes’ diameter of purified rHDL particles was determined by comparing their size exclusion chromatography distribution coefficient values (Kav) with those of globular proteins of known size from Sigma: porcine thyroid thyroglobulin, 17.0 nm; equine spleen ferritin, 12.2 nm; bovine heart lactate dehydrogenase, 8.2 nm; bovine serum albumin, 7.1 nm. Kav was calculated as (Ve − V0)/(Vt − V0), where V0 is the void volume, Vt is the total interstitial volume, and Ve is the elution volume. The diameters were plotted against [−log(Kav)]1/2 of the standard proteins. The points were fitted by linear regression analysis (R2 = 0.988), and the hydrodynamic diameter of rHDL samples of unknown size was calculated using eq 1.

| (1) |

Cross-Linking

To determine the number of apoA-I molecules per particle, rHDL samples were treated for 2 h at room temperature with DMS (dimethyl suberimidate) according to the procedure of Swaney et al. (34). Samples were separated in the presence of SDS on precast 4–20% polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA).

Nondenaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (NDGGE)

Gels (4–20% acrylamide) loaded with rHDL particles were run to termination at 1500 V • h under nondenaturing conditions and then stained with GelCode Blue stain reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Particle size was assigned by comparison to protein standards of known Stokes’ diameters [High Molecular Weight Calibration Kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ): thyroglobulin, 17.0 nm; ferritin, 12.2 nm; catalase, 10.0 nm; lactate dehydrogenase, 8.2 nm; serum albumin, 7.1 nm] (24, 32). The log of particle size was plotted against Rf of the standards; the points were fitted (R2 = 0.997; eq 2), and the particle size (nm) of rHDL samples was calculated by interpolation.

| (2) |

Electron Microscopy

Aliquots (2.5 µL) of rHDL samples were adhered to carbon-coated, 400-mesh copper grids previously rendered hydrophilic by glow discharge (35). The grids were washed for 1 min with three successive drops of deionized water and then exposed to three successive drops of 2% (w/v) sodium phosphotungstate acetate for 1 min (Ted Pella, Tustin, CA). Images at 67000× magnification were recorded on a 4K × 4K Gatan UltraScan CCD under low electron dose conditions using a FEI Tecnai Spirit electron microscope (Philips Electron Optics/FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) operating at 120 kV (36). Each pixel of the micrographs corresponds to 0.173 nm at the level of the specimen. Each box size is 116 pixels, corresponding to 20 nm in the specimen.

LCAT Activation Assay

LCAT activation by rHDL was monitored by following the conversion of cholesterol to cholesteryl ester. rHDL particles were reconstituted at the same POPC:apoA-I ratios described before but without free cholesterol. Five rHDL subclasses were purified by the protocol described above, and no differences were detected between FC containing and FC-free rHDL particles by NDGGE and chemical composition (POPC:apoA-I ratio) analysis. [1,2-3H]Cholesterol was introduced exogenously into the rHDL complexes following the method described by Jonas et al. (15, 16). rHDL samples were diluted in TBS to an apoA-I concentration ranging from 0.02 and 0.67 µM. Each concentration of rHDL was equilibrated with radiola-beled cholesterol by incubation at 37 °C for 30 min with 1.39 pmol of [1,2-3H]cholesterol (57.6 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences Inc., Boston, MA). The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in the presence of 5 mg/mL (final) BSA and 4 mM (final) β-mercaptoethanol. LCAT (50 ng) was added, and the reaction was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C (20, 27, 37); the reactions were terminated by the addition of 1 mL of absolute ethanol. Lipids were extracted with hexane, and the cholesterol and cholesteryl ester were separated by thin-layer chromatography using hexane–ethyl ether–acetic acid (108:30:1.2 v/v/v) as the solvent phase (12). The lipid spots were visualized under iodine vapor and recovered for scintillation analysis (Beckman Coulter LS 6500 multipurpose scintillation counter, Fullerton, CA). The LCAT reaction conditions were chosen on the basis of the linear response range of LCAT. Apparent Vmax and apparent Km for the reaction were determined using Lineweaver–Burk plots.

RESULTS

Synthesis and Purification of rHDL Particles

To study the dependence of particle stability and LCAT activation on rHDL particle size, we used the POPC–deoxycholate dialysis reconstitution method to prepare a comprehensive spectrum of rHDL subclasses, including the previously uncharacterized ∼8.4 nm diameter particle. The strategy for rHDL particle synthesis employed various ratios of phospholipid, free cholesterol, and apoA-I in concert with the well-established deoxycholate dialysis method to produce specific rHDL subclasses. To remove unincorporated lipids and protein, the lipidation mixtures were subjected to discontinuous gradient density ultracentrifugation. Subclasses of the rHDL particle were then prepared by high-resolution size exclusion chromatography with a Superdex-200 column.

A POPC, FC, and apoA-I molar ratio of 30:2:1 was optimal for the generation of 7.8 and 8.4 nm rHDL particles, whereas a higher POPC:FC:apoA-I ratio of 80:4:1 was optimal for the production of the 9.6 nm rHDL subclass (Table 1). Increases in lipid:protein ratios shifted the distribution of rHDL to species larger than 9.6 nm, predominantly 12.2 and 17.0 nm particles (Figure 1A).

Table 1.

Phospholipid:Free Unesterified Cholesterol:Protein Ratios Used for Synthesis of rHDL Particles

| POPC:FC:apoA-I (mol/mol) |

predominant rHDL particle size (nm) |

|---|---|

| 30:2:1 | 7.8, 8.4 |

| 80:4:1 | 9.6 |

| 160:8:1 | 12.2, 17.0 |

FIGURE 1.

Nondenaturing gel electrophoresis analysis of rHDL particles. Lanes 1, 5, 11, and 17 in gels A, B, C, and D: molecular weight markers (High Molecular Weight Calibration Kit from GE Healthcare) (24, 32). Gel A: Unpurified lipidation mixtures. Lanes 2, 3, and 4, respectively: 30:2:1, 80:4:1, and 160:8:1 POPC:FC:apoA-I ratios (mol/mol). Gel B: Isolated single size particles. Lanes 6 and 7: 7.8 and 8.4 nm rHDL particle purified from 30:2:1 (POPC:FC:apoA-I) lipidation mixture. Lane 8: 9.6 nm rHDL particle purified from 80:4:1 (POPC:FC:apoA-I) lipidation mixture. Lanes 9 and 10: 12.2 and 17.0 nm rHDL particle purified from 160:8:1 (POPC:FC:apoA-I) lipidation mixture. Gel C: Particle samples after 4 months storage at 4 °C. Lanes 12–16, respectively: 7.8, 8.4, 9.6, 12.2, and 17.0 nm. Gel D: Low mobility band from the 9.6 nm particle stored at 4 °C for 4 months (lane 14) repurified by size exclusion chromatography (lane 18).

The five classes of rHDL particles exhibited diameters of 7.8, 8.4, 9.6, 12.2, and 17.0 nm as assessed by NDGGE. Particles of 7.8 and 9.6 nm diameter have been described and characterized (24, 32); however, the isolation of 8.4 nm particles has not previously been reported (Figure 3), likely due to their low abundance, their similarity in size to the 7.8 nm particles, and their relatively short half-life (∼1 week at 37 °C; see below). Particles of 9.6 nm diameter were the most efficiently prepared, with an average final yield, as measured by protein content, of ∼33%, whereas 8.4 and 12.2 nm diameter particles were the two most difficult to isolate, with yields of 9.2% and 8.2%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Size and Average Final Purification Yields of Reconstituted HDL Particles

| rHDL particle size by NDGGE (nm)a |

rHDL particle hydrodynamic diameter (nm)b |

rHDL particle size by EM (nm)c |

final yield (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.8 ± 0.1 | 7.9 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.9 | 19.1 ± 11.2 (n = 14)e |

| 8.4 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 0.2 | 8.0 ± 1.1 | 9.2 ± 6.3 (n = 8)e |

| 9.6 ± 0.4 | 9.6 ± 0.4 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | 32.8 ± 11.3 (n = 11)f |

| 12.2 ± 0.8 | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 8.2 ± 4.7 (n = 6)g | |

| 17.0 ± 1.6 | 15.9 ± 0.6 | 12.5 ± 3.5 (n = 6)g | |

| spherical rHDLh | 8.4 ± 0.6 |

As determined by NDGGE (see Experimental Procedures). Values ± SD are the average of at least three sample preparations run on individual gels.

As determined by size exclusion chromatography (see Experimental Procedures). Values ± SD are the average of at least five individual preparations.

As determined by electron microscopy (see Experimental Procedures). Values ± SD are the average of the measures of the long axis for 50–100 particles per rHDL subclass.

The final yield was calculated relative to the initial amount of protein used for lipidation. Values ± SD are the average of at least six individual preparations.

Reconstituted from starting molar ratio of 30:2:1 POPC:FC:apoA-I.

Reconstituted from starting molar ratio of 80:4:1 POPC:FC:apoA-I.

Reconstituted from starting molar ratio of 160:8:1 POPC:FC:apoA-I.

Spherical rHDL were provided by Dr. Kerry-Anne Rye and were generated using methods described in ref 55.

The protein and lipid compositions of the isolated rHDL particles fall within the range previously reported by other investigators (Table 3). The variation in composition observed by different investigators likely reflects differences in the homogeneity of the rHDL subclasses as well as the intrinsic imprecision of the assays employed.

Table 3.

Reconstituted HDL Particle Compositions (POPC:FC:ApoA-I, mol/mol)

| current study | from ref 32 | from ref 56 | from ref 57 | from ref 29 | from ref 15 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| size (nm) | initial | finala | initial | final | initial | final | initial | final | initial | final | initial | final | |

| 7.8 | POPC | 30 | 34.0 ± 4.1 | 30 | 25 ± 2 | 34 | 55 ± 6 | 85 | 45 ± 4 | 88 | 39.3 ± 12.4 | 80 | 42 |

| FC | 2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 4 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 8 | 5 | |||||

| apoA-I | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 8.4 | POPC | 30 | 52.7 ± 10.7 | ||||||||||

| FC | 2 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | |||||||||||

| apoA-I | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 9.6 | POPC | 80 | 90.6 ± 8.6 | 78 | 75 ± 6b | 85 | 90 ± 6b | 120 | 103.5 ± 9.8 | 80 | 72f | ||

| FC | 4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 4 | 5 ± 1 | 6 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 8 | 6 | |||||

| apoA-I | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 12.2 | POPC | 160 | 140.3 ± 19.6 | 128 | 148 ± ld | 120 | 126.2 ± 10.9e | 80 | 82g | ||||

| FC | 8 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 6 | 6.6 ± 2 | 8 | 19 | |||||||

| apoA-I | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 17.0 | POPC | 160 | 174.2 ± 13.9 | 85 | 135 ± 7c | 120 | 171.4 ± 21.5 | ||||||

| FC | 8 | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 6 | 13.6 ± 5.7 | |||||||||

| apoA-I | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

Final molar composition of purified rHDL particles was assayed as described in Experimental Procedures. Values ± SD are the average of four to ten individual preparations.

9.8 nm.

16.0 nm.

12.7 nm.

13.4 nm.

8.6 + 9.6 nm mix.

10.9 nm.

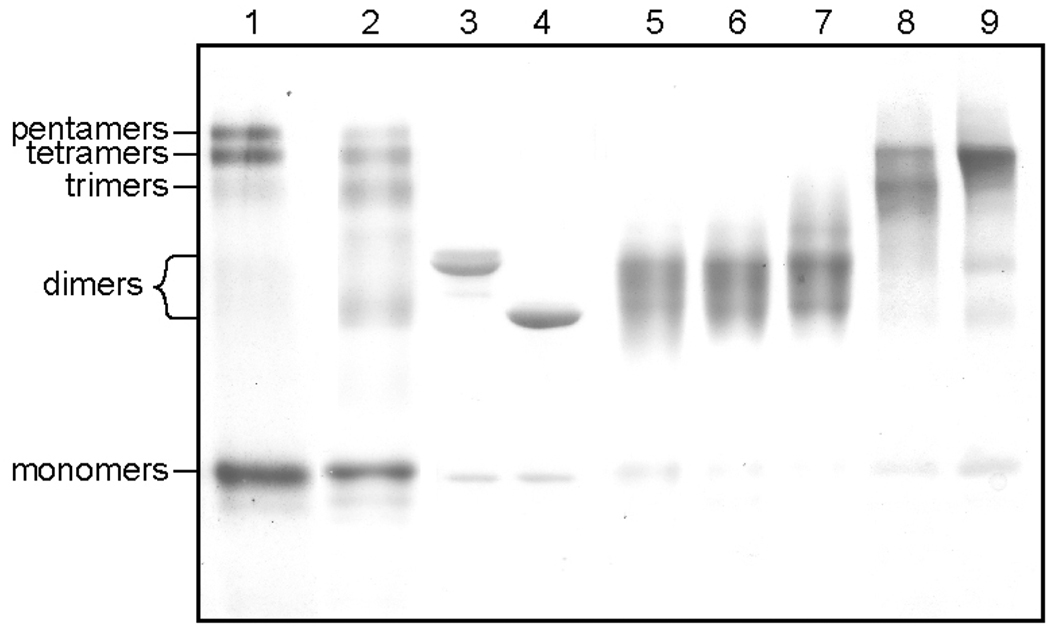

The number of apoA-I molecules present on different size rHDL particles was determined by dimethyl suberimidate cross-linking. Cross-linked apoA-I from 7.8, 8.4, and 9.6 nm diameter particles migrates on SDS–PAGE similar to dimeric cross-linked wild-type lipid-free apoA-I (lanes 1 and 2, Figure 2). Cross-linked apoA-I from 12.2 nm diameter particles was intermediate between the trimeric and tetrameric controls, while cross-linked apoA-I from 17.0 nm diameter particles was tetrameric.

FIGURE 2.

Stoichiometric analysis of apoA-I on rHDL by DMS cross-linking (see Experimental Procedures). Lane 1: Lipid-free WT apoA-I:DMS, 1:935 (mol/mol). Lane 2: Lipid-free WT apoA-I: DMS, 1:10. Lane 3: E136C mutant apoA-I, no DMS. Lane 4: E146C mutant apoA-I, no DMS. Lanes 5–9: apoA-I:DMS, 1:935 (mol/mol). Respectively, 7.8, 8.4, 9.6, 12.2, and 17.0 nm WT rHDL. Oligomeric species yield and mobility are also dependent on the ratio of protein to DMS (e.g., lanes 1 and 2). As the ratio of DMS to lipid-free WT apoA-I increases (lane 1 vs lane 2), the yield of dimeric products is very low compared to higher molecular weight oligomers. Because dimeric apoA-I can migrate in a broad range of apparent molecular weights, we reproduced this range using cysteine bearing apoA-I, which forms disulfide dimers with variable migration properties (lanes 3 and 4).

Electron Microscopic Analysis of rHDL

We used negative stain electron microscopy to investigate the uniformity and morphology of rHDL particles containing two molecules of apoA-I. rHDL with diameters of 7.8 nm (Figure 4A,B), 8.4 nm (Figure 4C,D), and 9.6 nm (Figure 4E,F) showed uniform particle populations, with apparent sizes consistent with those derived from NDGGE measurements.

FIGURE 4.

Electron microscopy of homogeneous samples of 7.8 nm (panels A and B), 8.4 nm (panels C and D), 9.6 nm (panels E and F), and spherical (panels G and H) rHDL particles. Spherical rHDL were provided by Dr. Kerry-Anne Rye and were generated with standard procedures, as described in ref 55. Bars in the left column equal to 20 nm. See Table 2 for EM sizing. Individual particles are shown enlarged in the right column with boxes of 20 × 20 nm. In the first row of panel F are side views, in the second row are top views, and in the third row are tilted views of individual 9.6 discoidal particles. In general, particle views were assigned by the convention put forth by Catte et al. (13). Briefly, top views were visually identified as the objects showing maximum surface area. Particles with minimal surface area and showing a bidimensional geometry were selected as side views. All particles showing an intermediate shape between the two mentioned above were assumed to represent tilted rHDL views.

Size-specific rHDL particle morphologies were observed by electron microscopy. Particles of 9.6 nm diameter displayed a disk-like geometry (Figure 4E,F), as confirmed by the higher degree of rouleaux formation, typical of discoidal HDL (12, 19, 38). In contrast, 7.8 nm particles (Figure 4A,B) appeared smaller, globular in shape, and with no observable rouleaux (38). The globular aspect of smaller (7.3–7.8 nm) particles resembles that of spherical rHDL (Figure 4G,H) and is consistent with the “figure-8” configuration of partially lipidated apoA-I predicted by Catte et al. using molecular dynamic simulations (13). The 8.4 nm particles (Figure 4C,D) bore an intermediate morphology with the major axis of length between a globular 7.8 nm and a flat-discoidal 9.6 nm particle. The degree of rouleaux formation in the 8.4 nm sample was significantly less than that of 9.6 nm particles, suggesting a reduced planar surface area. Particle size was calculated by averaging long axis measurements of 50–100 particles per rHDL subclass (Table 2). The relative average rHDL particle diameter measured by EM was consistent with the NDGGE and size exclusion chromatography sizing. As previously reported (11, 15), the EM results do not precisely match the data from other physical techniques. Here, interestingly, EM-derived diameters of the 7.8 and 8.4 nm particles are significantly smaller than expected from NDGGE and size exclusion chromatography sizing, whereas no significant differences in the sizing of the larger 9.6 nm particle were observed. This result is consistent with the morphological differences in rHDL subclasses. Because of the discoidal shape of the 9.6 nm particle, it presents itself with a more consistent diameter or long axis, whereas the 7.8 and 8.4 nm particles are more globular and thus present a less consistent view of their long axis due to their asymmetrical shape. This is also demonstrated by the greater variability in 7.8 and 8.4 nm particle sizing by EM.

rHDL Size-Dependent Activation of LCAT

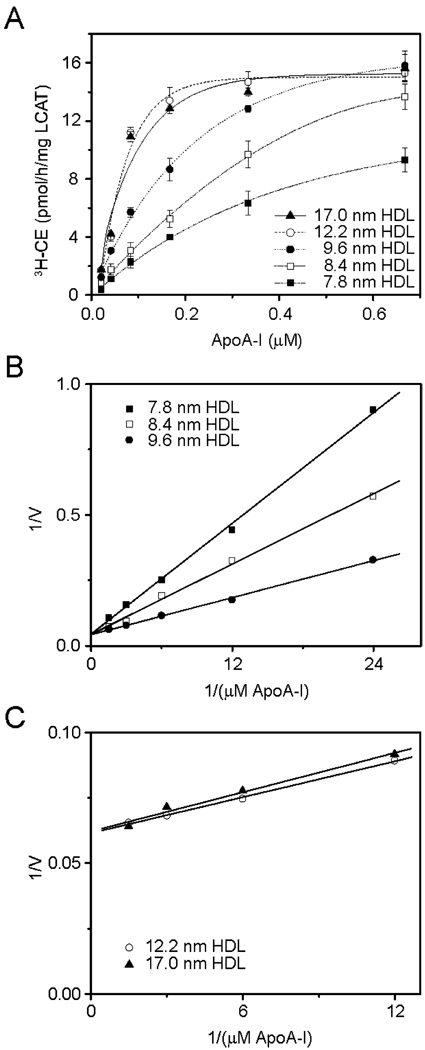

The ability of the different subclasses of rHDL to activate LCAT was evaluated by measuring the rate of conversion of FC to CE (Figure 5). Importantly, until now a complete assessment of POPC-based rHDL species has not been possible, due in part to the difficulty of purifying the 8.4 nm rHDL particle.

FIGURE 5.

HDL concentration-dependent activation of LCAT by rHDL particles of different size. LCAT activation by rHDL was monitored by following the cholesterol to cholesteryl ester conversion. After rHDL particles were incubated with radiolabeled cholesterol, BSA, and β-mercaptoethanol, the indicated amount (apoA-I concentration) of rHDL particles of different size was incubated with 50 ng of LCAT at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction was terminated with ethanol, and then CE was separated from cholesterol and quantified as described in Experimental Procedures. Panels B and C: Lineweaver–Burk linear regression analysis. Plot of the reciprocals of initial velocities vs reciprocals of apoA-I concentrations for 7.8, 8.4, and 9.6 nm rHDL (panel B) and 12.2 and 17.0 nm rHDL (panel C), respectively.

Activation of LCAT at a variety of particle concentrations was proportionate to particle size. Similar results have been reported for LCAT activation by 7.8 and 9.6 nm rHDL subclasses (23–25). The ability of 8.4 nm rHDL particles to activate LCAT is consistent with this trend and was intermediate between that of 7.8 and 9.6 nm particles (Figure 5). Intriguingly, 12.2 and 17.0 nm rHDL particles had similar LCAT activation properties and were more efficient than the 9.6 nm rHDL in promoting cholesterol esterification, although their apparent Vmax was lower than that of rHDL containing two molecules of apoA-I (Table 4). The increase in catalytic efficiency (apparent Vmax/apparent Km) of rHDL particles containing more than two apoA-I molecules was due to a 7-fold drop in their apparent Km.

Table 4.

Reaction of rHDL Particles of Different Size with LCAT

| rHDL particle size (nm) |

app Vmax [pmol of CE h−1 (µg of LCAT)−1]a |

app Km (µM apoA-I)a |

app Vmax/ app Km |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.8 | 22.30 ± 0.41 | 0.786 ± 0.027 | 28.37 ± 0.75 |

| 8.4 | 23.01 ± 4.02 | 0.515 ±0.153 | 44.68 ± 4.75 |

| 9.6 | 23.36 ± 5.06 | 0.275 ± 0.084 | 84.95 ± 8.64 |

| 12.2 | 16.26 ± 0.34 | 0.037 ± 0.004 | 439.46 ± 50.01 |

| 17.0 | 16.10 ± 1.91 | 0.040 ± 0.010 | 402.50 ± 19.81 |

The apparent kinetic parameters are the mean ± SD from three independent LCAT assays.

Stability of rHDL Particles

rHDL containing two apoA-I molecules exhibit a variety of sizes and morphologies, suggesting that there may be differences in rHDL subclass stability. We therefore examined the stability of the five rHDL subclasses as determined by NDGGE immediately after isolation of the particles and after storage at 4 °C for 4 months. All samples remained fully soluble without evidence of aggregation (as assessed by light scattering analysis), and there was no evidence of apoA-I degradation as assessed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblot analysis (data not shown). However, rHDL sample size composition was altered during storage, resulting in conversion of homogeneous populations of rHDL to mixtures of different size particles (Figure 1C). The 8.4 nm particles were the most dynamic, with more than 80% of the sample converted to 7.8 nm particles. Interestingly, the 7.8 nm particles were highly stable, with no detectable appearance of other sizes of rHDL particles. The 9.6 nm diameter rHDL were intermediate in stability, and ∼30% of the particles remodeled to 7.8 nm particles. Consistent with these observations, small 7.3 nm HDL particles were previously reported as the most thermodynamically stable among 11.0, 9.0, and 7.3 nm particles isolated from CHO cell medium (38). In our study, larger rHDL containing three or four apoA-I molecules were also very stable. No change in the 12.2 and 17.0 nm particle preparation composition was observed after 4 months of storage at 4 °C. Spherical rHDL containing three molecules of apoA-I (the majority of circulating HDL) is also relatively more stable than rHDL containing two molecules of apoA-I (16), suggesting that the additional apoA-I may significantly enhance particle stability.

A slow mobility band migrating in native PAGE to approximately the same degree as a 12 nm diameter rHDL appeared in the 9.6 nm rHDL sample during prolonged incubations (Figure 1C, lane 14). The particles composing this band were isolated by high-resolution size exclusion chromatography (Figure 1D, lane 18). The POPC:apoA-I molar ratio of the isolated material was approximately 3:1, suggesting that it was a lipid-poor species of apoA-I. The apparent ∼12 nm Stokes’ diameter of this lipid-poor form of apoA-I is likely due to oligomerization of the apolipoprotein (39–41).

The appearance of lipid-poor apoA-I in the 9.6 nm rHDL particle subclass suggests that apoA-I can transition between lipid-bound and lipid-poor states during rHDL remodeling and that this process can be independent of enzymes and lipid transfer proteins carried by circulating HDL particles.

To better understand the dynamic nature of the 8.4 nm rHDL particles, we examined rates of particle size redistribution at 4 and at 37 °C (panels A and B of Figure 6, respectively). As expected, the rate at which 8.4 nm particles remodeled to other sized particles was highly temperature dependent, and greater than 60% of the sample transitioned to 7.8 nm rHDL after only 7 days at 37 °C. Storage at 4 °C dramatically reduced the rate of particle remodeling, but after 14 days a significant percentage (>40%) of the 8.4 nm sample was transformed to the smaller 7.8 nm rHDL species. It is noteworthy that long-term incubation at 4 °C produced mostly 7.8 nm rHDL with a small percentage (<10%) of 9.6 nm rHDL, whereas after 2 months of incubation at 37 °C only the 7.8 nm species was observable. Interestingly, the 7.8, 9.6, 12.2, and 17.0 nm rHDL particles did not show the same degree of particle remodeling under the same incubation conditions, which confirms the relatively dynamic nature of the 8.4 nm particles.

FIGURE 6.

Nondenaturing gel electrophoresis analysis of 8.4 nm rHDL particle remodeling over a period of 2 months at 4 °C (A) or at 37 °C (B). Markers are High Molecular Weight Calibration Kit from GE Healthcare (24, 32).

The low mobility bands characterized as lipid-poor apoA-I oligomers were readily detected by NDDGE after only 2 days of incubation at 37 °C. In contrast, 2 months of incubation at 4 °C was required for lipid-poor apoA-I to accumulate in equivalent amounts. The temperature dependence of rHDL particle remodeling and the maintenance of solubility suggest that the process is due to specific conformational changes of apoA-I and not a result of general dissociation of rHDL lipid components.

DISCUSSION

There is intense interest in HDL as a therapeutic target in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. However, both human and animal studies strongly suggest that levels of HDL–cholesterol alone do not necessarily predict the cardioprotective effects of the lipoprotein. Therefore, it is important to better understand the factors that regulate the ability of HDL to promote RCT.

In the current study we investigated the effect of rHDL particle size on particle morphology, stability, and biological activity. A key element of this study was the comprehensive range of rHDL subclasses examined, including the previously uncharacterized 8.4 nm diameter POPC rHDL particles.

The defined subclasses of rHDL particle sizes produced by apoA-I are likely a product of the limited number of conformational states that this apolipoprotein can assume. Both molecular dynamic simulations (42) and experimental observations (43, 44) support the notion that intermolecular salt bridges and/or proline stacking maintain(s) the antiparallel alignment of paired apoA-I molecules on the perimeter of HDL particles. These stabilizing forces are present in a highly defined set of apoA-I conformations. The quantized distribution of HDL particle sizes also limits the possible mechanisms by which HDL can interconvert between particle subclasses. Because the population of rHDL particles produced by apoA-I is discrete rather than a continuum of sizes, it is unlikely that HDL particles are assembled in vivo by simple accretion of lipid from cell membranes or other lipid sources.

The electron micrographs of the 7.8, 8.4, and 9.6 nm rHDL particles illustrate the remarkable size-specific differences in particle shape and morphology (Figure 4). Prior to the molecular dynamic modeling of Catte et al. (13), larger and smaller rHDL containing two molecules of apoA-I were perceived to differ in only the diameter of a discoidal complex. Our EM data are consistent with the models of Catte et al., wherein changes in lipid content lead to morphological changes in HDL particles (figure-8 versus disk) rather than a simple increase in the diameter of a phospholipid disk. The degree of rouleaux formation observed in 7.8, 8.4, and 9.6 nm rHDL by negative stain electron microscopy is a reflection of the morphological spectrum of these particles, going from the globular shape of the 7.8 nm rHDL (no rouleaux) to the discoidal shape of the 9.6 nm rHDL (rouleaux forming).

By examining the ability of a full spectrum of rHDL particle sizes to activate LCAT, we demonstrated a direct relationship between rHDL size and LCAT activation. Previous reports consistently referred to 9.6 nm rHDL as the optimal LCAT activator; however, our data are in agreement with the findings of Meng et al. (29), wherein rHDL particles reported as containing three molecules of apoA-I (13.4 and 17.0 nm diameter rHDL) were more effective LCAT activators than rHDL particles containing two molecules of apoA-I. This is the only prior observation of increased LCAT activation for rHDL particles containing more than two molecules of apoA-I, but unfortunately no detailed kinetic analysis was performed.

Conformational changes of apoA-I in concert with changes in the morphology of HDL likely account for the effect of HDL size on LCAT activation (4).

There are several possible mechanisms by which the conformation of apoA-I may influence LCAT’s binding to HDL (45). The “looped belt” model (46) suggests that the number of residues composing the loop domain may be different for particles of diameter smaller than 9.6 nm, thereby forcing the LCAT binding region(s) of the apolipoprotein out of their optimal alignment. Additionally, any rearrangement of the disk morphology, like the one proposed by the molecular dynamic analysis of Catte et al. (13), may rotate the LCAT binding regions into positions less available for LCAT binding (24). It is also possible that the central loop of apoA-I may serve as an access portal to FC incorporated into the lipid bilayer (46), which on larger HDL particles may be in a more “open” conformation. Thus rHDL size-dependent conformational changes in the apoA-I central loop may modulate either the binding of LCAT to HDL or the accessibility of substrate to LCAT’s catalytic site.

Differences in LCAT activation may also be due to changes in HDL morphology/shape (i.e., nonplanar versus planar discoidal shape) that do not alter the optimal alignment of apoA-I’s LCAT binding sites but rather affect the intraparticle cholesterol diffusion rate and thus the availability of FC to LCAT’s catalytic site.

In this study, detailed kinetic analysis of LCAT activation properties of the different size subclasses of rHDL reveals the involvement of different contributing factors to the size-dependent activation of LCAT. The differences in Km values for similar Vmax account for the rHDL size-dependent LCAT activation within rHDL subclasses containing two molecules of apoA-I. The morphological differences between 7.8, 8.4, and 9.6 nm HDL particles, as observed by EM, suggest that particle morphology can play a significant role in LCAT activation for these rHDL. However, traditional LCAT activation assays (15, 23, 26, 27, 47) simply monitor the formation of LCAT reaction products (CE) and cannot distinguish between the contributions of changes in LCAT-HDL binding from localized substrate availability to LCAT’s active site. The apparent Km would be affected in both scenarios. In the case of substrate availability, LCAT binds to all HDL sizes with similar affinity, but the accessibility of unesterified cholesterol to LCAT’s catalytic site may be altered by changes in apoA-I conformation or HDL particle morphology. The discoidal shape of 9.6 nm HDL would be the most efficient among HDL subclasses containing two apoA-I molecules to present unesterified cholesterol to LCAT’s active site. We are currently in the process of evaluating the direct binding of LCAT to the full repertoire of rHDL particles to discern between these possibilities.

The significant nonlinear reduction in apparent Km between rHDL subclasses containing two apoA-I molecules (Km, 0.8–0.3) and greater than two apoA-I molecules (Km ≈ 0.04) indicates the presence of a conformational contribution of apoA-I to LCAT activity, which is further confirmed by the similar LCAT activation of 12.2 and 17.0 nm rHDL. We hypothesize that the presence of additional apoA-I molecules on 12.2 and 17.0 nm rHDL particles imparts changes to apoA-I’s conformation that facilitate LCAT binding. These observations suggest that LCAT activation is governed by two processes: on rHDL containing two apoA-I molecules, LCAT activation is predominantly modulated by morphological variation of the rHDL particle, whereas conformational changes on rHDL containing three or four apoA-I molecules may be the primary regulator that leads to enhanced rHDL–LCAT interaction.

In addition to rHDL particle morphology and LCAT activation, we demonstrated that stability is also a size-dependent property of rHDL. The globular 7.8 nm and the discoidal 9.6 nm particles are relatively more stable than the 8.4 nm particles, which are intermediate in size and morphology. These particles readily and spontaneously remodel to other rHDL subclasses in a temperature-dependent manner.

Previous studies investigating HDL particle remodeling used HDL fractions supplemented with lipid-free apoA-I (38), LDL (17, 18), enzymes [cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) (48, 49); phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) (50, 51)], or cells (38). Prior to this study, spontaneous rHDL particle remodeling had not been thoroughly investigated. Intriguingly, we identified a pool of lipid-poor apoA-I which spontaneously forms when 8.4 and 9.6 nm rHDL particles are incubated at 4 or 37 °C. This finding supports the hypothesis that lipid-poor apoA-I serves to shuttle phospholipids between different HDL particle subclasses (10, 38, 52). The genesis of HDL particles containing more than two apoA-I molecules has been a longstanding subject of debate. One hypothesized mechanism for the formation of these particles is the fusion of two HDL particles containing two apoA-I molecules to produce one HDL particle containing three apoA-I molecules with the release of one apoA-I in lipid-poor form (53). However, LCAT is capable of incorporating exogenous lipid-free apoA-I into HDL containing two apoA-I molecules (54). The production of lipid-poor apoA-I from spontaneous remodeling events is an alternative source of lipid-poor apoA-I that can serve as a substrate for LCAT-driven processes. Thus it is likely that both mechanisms may operate in tandem in vivo, maximizing the association of apoA-I with HDL and minimizing apoA-I clearance from circulation.

Furthermore, the in vivo generation of nascent HDL via the ABCA1-mediated pathway is dependent on the presence of lipid-free/lipid-poor apoA-I. It is plausible that the lipid-free/lipid-poor apoA-I derived from spontaneous HDL remodeling may contribute to ABCA1-mediated HDL assembly.

In summary, we have shown that there is a direct relationship between HDL size, apoA-I content, and LCAT activation. We also found that different subclasses of particles have distinct morphology and stability and that spontaneous remodeling of HDL particles represents a potential mechanism for the generation of lipid-poor apoA-I in RCT. In future studies, it will be important to further investigate the role of the additional apoA-I molecules on larger rHDL (>9.6 nm) in LCAT activation and the interplay between HDL remodeling events and the production of lipid-poor apoA-I necessary for cholesterol efflux in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. John Parks and Dr. Kerry-Anne Rye for generously providing human LCAT and spherical rHDL particles, respectively. We also thank Dr. Trudy M. Forte and Dr. Robert O. Ryan for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HL77268, HL086708, HL086798, and HL030086 and by the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program of California, Grant 16FT-0163. G.C. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program of California (Grant 16FT-0054). B.S. was supported by a Fellowship Award from the Phillip Morris External Research Program (Philip Morris USA Inc. and Philip Morris International). G.R. was supported by funds from the W. M. Keck Advanced Microscopy Laboratory at UCSF.

Abbreviations: ABCA1, ATP binding cassette transporter A1; apoA-I, apolipoprotein A-I; CE, cholesteryl ester; EM, electron microscopy; FC, free unesterified cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein(s); LCAT, lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase; LDL, low-density lipoprotein(s); NDGGE, nondenaturing gradient gel electrophoresis; RCT, reverse cholesterol transport; rHDL, reconstituted high-density lipoprotein; SEC, size exclusion chromatography; DC, sodium deoxycholate; TBS, Tris-buffered saline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fielding CJ, Fielding PE. Molecular physiology of reverse cholesterol transport. J. Lipid Res. 1995;36:211–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oram JF, Heinecke JW. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1: a cell cholesterol exporter that protects against cardiovascular disease. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:1343–1372. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Eckardstein A, Nofer JR, Assmann G. High density lipoproteins and arteriosclerosis. Role of cholesterol efflux and reverse cholesterol transport. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2001;21:13–27. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonas A. Regulation of lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase activity. Prog. Lipid Res. 1998;37:209–234. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(98)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodzioch M, Orso E, Klucken J, Langmann T, Bottcher A, Diederich W, Drobnik W, Barlage S, Buchler C, Porsch-Ozcurumez M, Kaminski WE, Hahmann HW, Oette K, Rothe G, Aslanidis C, Lackner KJ, Schmitz G. The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:347–351. doi: 10.1038/11914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawn RM, Wade DP, Garvin MR, Wang X, Schwartz K, Porter JG, Seilhamer JJ, Vaughan AM, Oram JF. The Tangier disease gene product ABC1 controls the cellular apolipoprotein-mediated lipid removal pathway. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:R25–R31. doi: 10.1172/JCI8119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seda O, Sedova L. New apolipoprotein A-V: comparative genomics meets metabolism. Physiol. Res. (Prague, Czech Repub.) 2003;52:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zannis VI, Chroni A, Krieger M. Role of apoA-I, ABCA1, LCAT, and SR-BI in the biogenesis of HDL. J. Mol. Med. 2006;84:276–294. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu S, Laccotripe M, Huang X, Rigotti A, Zannis VI, Krieger M. Apolipoproteins of HDL can directly mediate binding to the scavenger receptor SR-BI, an HDL receptor that mediates selective lipid uptake. J. Lipid Res. 1997;38:1289–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rye KA, Barter PJ. Formation and metabolism of prebeta-migrating, lipid-poor apolipoprotein A-I. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:421–428. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000104029.74961.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols AV, Gong EL, Blanche PJ, Forte TM. Characterization of discoidal complexes of phosphatidylcholine, apolipoprotein A-I and cholesterol by gradient gel electrophoresis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1983;750:353–364. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(83)90040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matz CE, Jonas A. Micellar complexes of human apolipoprotein A-I with phosphatidylcholines and cholesterol prepared from cholate-lipid dispersions. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:4535–4540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catte A, Patterson JC, Jones MK, Jerome WG, Bashtovyy D, Su Z, Gu F, Chen J, Aliste MP, Harvey SC, Li L, Weinstein G, Segrest JP. Novel changes in discoidal high density lipoprotein morphology: a molecular dynamics study. Biophys. J. 2006;90:4345–4360. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Chen J, Mishra VK, Kurtz JA, Cao D, Klon AE, Harvey SC, Anantharamaiah GM, Segrest JP. Double belt structure of discoidal high density lipoproteins: molecular basis for size heterogeneity. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;343:1293–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonas A, Kezdy KE, Wald JH. Defined apolipoprotein A-I conformations in reconstituted high density lipoprotein discs. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:4818–4824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonas A, Wald JH, Toohill KL, Krul ES, Kezdy KE. Apolipoprotein A-I structure and lipid properties in homogeneous, reconstituted spherical and discoidal high density lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:22123–22129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho KH, Durbin DM, Jonas A. Role of individual amino acids of apolipoprotein A-I in the activation of lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase and in HDL rearrangements. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:379–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durbin DM, Jonas A. Lipid-free apolipoproteins A-I and A-II promote remodeling of reconstituted high density lipoproteins and alter their reactivity with lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase. J. Lipid Res. 1999;40:2293–2302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duong PT, Collins HL, Nickel M, Lund-Katz S, Rothblat GH, Phillips MC. Characterization of nascent HDL particles and microparticles formed by ABCA1-mediated efflux of cellular lipids to apoA-I. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:832–843. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500531-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krimbou L, Hajj Hassan H, Blain S, Rashid S, Denis M, Marcil M, Genest J. Biogenesis and speciation of nascent apoA-I-containing particles in various cell lines. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:1668–1677. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500038-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denis M, Haidar B, Marcil M, Bouvier M, Krimbou L, Genest J., Jr Molecular and cellular physiology of apolipoprotein A-I lipidation by the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7384–7394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frank PG, N’Guyen D, Franklin V, Neville T, Desforges M, Rassart E, Sparks DL, Marcel YL. Importance of central alpha-helices of human apolipoprotein A-I in the maturation of high-density lipoproteins. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13902–13909. doi: 10.1021/bi981205b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonas A, Zorich NL, Kezdy KE, Trick WE. Reaction of discoidal complexes of apolipoprotein A-I and various phosphatidylcholines with lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase. Interfacial effects. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:3969–3974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander ET, Bhat S, Thomas MJ, Weinberg RB, Cook VR, Bharadwaj MS, Sorci-Thomas M. Apolipoprotein A-I helix 6 negatively charged residues attenuate lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) reactivity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5409–5419. doi: 10.1021/bi047412v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolin DJ, Jonas A. Sphingomyelin inhibits the lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase reaction with reconstituted high density lipoproteins by decreasing enzyme binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:19152–19158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorci-Thomas MG, Curtiss L, Parks JS, Thomas MJ, Kearns MW. Alteration in apolipoprotein A-I 22-mer repeat order results in a decrease in lecithin:cholesterol acyltrans-ferase reactivity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:7278–7284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorci-Thomas M, Kearns MW, Lee JP. Apolipoprotein A-I domains involved in lecithin-cholesterol acyltrans-ferase activation. Structure:function relationships. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:21403–21409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McManus DC, Scott BR, Frank PG, Franklin V, Schultz JR, Marcel YL. Distinct central amphipathic alpha-helices in apolipoprotein A-I contribute to the in vivo maturation of high density lipoprotein by either activating lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase or binding lipids. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:5043–5051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng QH, Calabresi L, Fruchart JC, Marcel YL. Apolipoprotein A-I domains involved in the activation of lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase. Importance of the central domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:16966–16973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan RO, Forte TM, Oda MN. Optimized bacterial expression of human apolipoprotein A-I. Protein Expression Purif. 2003;27:98–103. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00568-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oda MN, Bielicki JK, Berger T, Forte TM. Cysteine substitutions in apolipoprotein A-I primary structure modulate paraoxonase activity. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1710–1718. doi: 10.1021/bi001922h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maiorano JN, Jandacek RJ, Horace EM, Davidson WS. Identification and structural ramifications of a hinge domain in apolipoprotein A-I discoidal high-density lipoproteins of different size. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11717–11726. doi: 10.1021/bi0496642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiske CH, SubbaRow Y. Colorimetric determiantion of phosphorous. J. Biol. Chem. 1925;66:357–400. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swaney JB, O’Brien K. Cross-linking studies of the self-association properties of apo-A-I and apo-A-II from human high density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:7069–7077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohi M, Li Y, Cheng Y, Walz T. Negative Staining and Image Classification–Powerful Tools in Modern Electron Microscopy. Biol. Proced. Online. 2004;6:23–34. doi: 10.1251/bpo70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen TS, Weers PM, Raussens V, Wang Z, Ren G, Sulchek T, Hoeprich PD, Ryan RO. Amphotericin B induces interdigitation of apolipoprotein stabilized nanodisk bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rye KA, Bright R, Psaltis M, Barter PJ. Regulation of reconstituted high density lipoprotein structure and remodeling by apolipoprotein E. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:1025–1036. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500525-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forte TM, Bielicki JK, Knoff L, McCall MR. Structural relationships between nascent apoA-I-containing particles that are extracellularly assembled in cell culture. J. Lipid Res. 1996;37:1076–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren X, Zhao L, Sivashanmugam A, Miao Y, Korando L, Yang Z, Reardon CA, Getz GS, Brouillette CG, Jerome WG, Wang J. Engineering mouse apolipoprotein A-I into a monomeric, active protein useful for structural determination. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14907–14919. doi: 10.1021/bi0508385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gianazza E, Calabresi L, Santi O, Sirtori CR, Franceschini G. Denaturation and self-association of apolipoprotein A-I investigated by electrophoretic techniques. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7898–7905. doi: 10.1021/bi962600+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vitello LB, Scanu AM. Studies on human serum high density lipoproteins. Self-association of apolipoprotein A-I in aqueous solutions. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:1131–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klon AE, Segrest JP, Harvey SC. Molecular dynamics simulations on discoidal HDL particles suggest a mechanism for rotation in the apo A-I belt model. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;324:703–721. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silva RA, Hilliard GM, Li L, Segrest JP, Davidson WS. A mass spectrometric determination of the conformation of dimeric apolipoprotein A-I in discoidal high density lipoproteins. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8600–8607. doi: 10.1021/bi050421z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhat S, Sorci-Thomas MG, Tuladhar R, Samuel MP, Thomas MJ. Conformational adaptation of apolipoprotein A-I to discretely sized phospholipid complexes. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7811–7821. doi: 10.1021/bi700384t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhoest A, Zhao Z, De Geest B, Deridder E, Sillen A, Engelborghs Y, Collen D, Holvoet P. Role of the Arg123-Tyr166 paired helix of apolipoprotein A-I in lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:15967–15972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin DD, Budamagunta MS, Ryan RO, Voss JC, Oda MN. Apolipoprotein A-I assumes a “looped belt” conformation on reconstituted high density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:20418–20426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laccotripe M, Makrides SC, Jonas A, Zannis VI. The carboxyl-terminal hydrophobic residues of apolipoprotein A-I affect its rate of phospholipid binding and its association with high density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17511–17522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rye KA, Hime NJ, Barter PJ. Evidence that cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reductions in reconstituted high density lipoprotein size involve particle fusion. J. Biol.Chem. 1997;272:3953–3960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang HQ, Rye KA, Barter PJ. Cycling of apolipoprotein A-I between lipid-associated and lipid-free pools. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1257:31–37. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00055-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lusa Ss, Jauhiainen M, Metso J, Somerharju P, Ehnholm C. The mechanism of human plasma phospholipid transfer protein-induced enlargement of high-density lipoprotein particles: evidence for particle fusion. Biochem. J. 1996;313(Part 1):275–282. doi: 10.1042/bj3130275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryan RO, Yokoyama S, Liu H, Czarnecka H, Oikawa K, Kay CM. Human apolipoprotein A-I liberated from high-density lipoprotein without denaturation. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4509–4514. doi: 10.1021/bi00133a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pownall HJ, Pao Q, Rohde M, Gotto AM. Lipoprotein-apoprotein exchange in aqueous systems: relevance to the occurrence of apoA-I and apoC proteins in a common particle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1978;85:408–414. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(78)80057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nichols AV, Blanche PJ, Gong EL, Shore VG, Forte TM. Molecular pathways in the transformation of model discoidal lipoprotein complexes induced by lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;834:285–300. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(85)90001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liang HQ, Rye KA, Barter PJ. Remodelling of reconstituted high density lipoproteins by lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase. J. Lipid Res. 1996;37:1962–1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rye KA, Garrety KH, Barter PJ. Preparation and characterization of spheroidal, reconstituted high-density lipoproteins with apolipoprotein A-I only or with apolipoprotein A-I and A-II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1167:316–325. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(93)90235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maiorano JN, Davidson WS. The orientation of helix 4 in apolipoprotein A-I-containing reconstituted high density lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17374–17380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calabresi L, Vecchio G, Frigerio F, Vavassori L, Sirtori CR, Franceschini G. Reconstituted high-density lipoproteins with a disulfide-linked apolipoprotein A-I dimer: evidence for restricted particle size heterogeneity. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12428–12433. doi: 10.1021/bi970505a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]