Abstract

Objective To evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of an enhanced cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT), Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training (PASCET-PI-2), for physical (obesity) and emotional (depression) disturbances in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Method In an open trial, 12 adolescents with PCOS, obesity, and depression underwent eight weekly sessions and three family-based sessions of CBT enhanced by lifestyle goals (nutrition and exercise), physical illness narrative (meaning of having PCOS), and family psychoeducation (family functioning). Results Weight showed a significant decrease across the eight sessions from an average of 104 kg (SD = 26) to an average of 93 kg (SD = 18), t(11) = 6.6, p <.05. Depressive symptoms on the Children's Depression Inventory significantly decreased from a mean of 17 (SD = 3) to a mean of 9.6 (SD = 2), t(11) = 16.8, p <.01. Conclusion A manual-based CBT approach to treat depression in adolescents with PCOS and obesity appears to be promising.

Keywords: cognitive–behavioral therapy, depression, obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, weight loss

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in women, with prevalence rates of 5–10% and diagnosis frequently during adolescence (Arslanian, Lewy, Danadian, & Saad, 2002). While the exact etiology of PCOS is unknown, two theories exist: (a) hypothalamic/pituitary dysregulation of luteinizing and follicle stimulating hormones leads to increased ovarian androgen production; or (b) hyperandrogenism occurs secondary to insulin resistance. According to the National Institute of Child Health and Development (Revised 2003 Consensus), a diagnosis of PCOS requires: (1) clinical or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism; (2) oligo-ovulation; and (3) exclusion of other known disorders. Hormonal imbalances in PCOS induce oligoovulation, which is associated with irregular menstruation, hirsutism, and acne. PCOS is increasingly being recognized in adolescent girls who seek treatment for hyperandrogenism (Arslanian & Witchel, 2002), and is frequently associated with obesity—70–74% in general outpatient clinics (Yildiz et al., 2007) and ∼99% in specialty care PCOS Centers (Rofey et al., 2007). It has also been theorized that deviant hormone levels alongside of obesity and negative body image contribute to the manifestation of severe depression in 40–45% of women with PCOS (Rofey et al., 2007). Thus, adolescents with PCOS present as an ideal treatment-seeking group given their visible and covert symptoms that have the potential to be extremely disruptive to adolescent development (Trent et al., 2005; Warren-Ulanch & Arslanian, 2006).

Evidence suggests that for adolescents with physical illness, emotional disturbances can have more insidious consequences influencing the expression and course of disease (Leventhal et al., 1998). Poor psychosocial functioning in adolescents with physical illness is associated with higher health care utilization/cost, less optimal medical outcomes, and increased mortality (Lernmark, Persson, Fisherm & Rydelius, 1999). There are few studies that address treatment efficacy of depression in physically ill adolescents (Walco & Ilowite, 1992), and only one manual-based treatment designed specifically to target depression for pediatric patients (Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training for Physical Illness, PASCET-PI; Szigethy et al., 2004). Existent studies targeting adolescents with PCOS have only provided base rates of depression (Himelein & Thatcher, 2006; Hollinrake et al., 2007; Rasgon et al., 2003; Weiner, Primeau, & Ehrmann, 2004) or targeted lifestyle goals with no emphasis or measurement of psychosocial functioning (Hoeger, 2006; Tang et al., 2006).

Given that adolescents with PCOS have a metabolic profile that can only moderately be controlled by medication (Warren-Ulanch & Arslanian, 2006), a behavioral intervention focusing on improving physical (obesity) and emotional (depression) disturbances is warranted. Therefore, we have modified the PASCET-PI (Szigethy et al., 2004, 2006, 2007) in adolescents to target comorbid depression symptoms and obesity using a cognitive–behavioral approach augmented by additional components. The modifications from the PASCET to the PASCET-PI can be found in a previous publication (Szigethy et al., 2004). For the purposes of the current investigation, the following components were added for the PASCET-PI-2 to target specific concerns raised by adolescents with PCOS: (Primary) healthy nutritional choices, increasing physical activity, and decreasing sedentary behavior; and (Secondary) increasing sleep and improving body image. Specifically, nutritional recommendations consisted of choosing foods that fall under 5 g of fat and 10 g of sugar; limiting beverages to <10 calories; and eating three meals and one snack per day consisting of one serving of protein, starch, and two servings of fruits/vegetables falling within a specified calorie range (Epstein, & Squires, 1988; Food Standard Agency, 2007; Stice, Shaw, & Marti, 2006). Second, physical activity targets were set at 10,000 steps per day on a pedometer and decreasing sedentary time to ∼2 hr per day. Last, given the empirically validated family-based treatment for pediatric obesity (Epstein, Myers, Raynor, & Saelens, 1998), the intervention included the participation of one supportive parent/guardian at the beginning and end of each session, in addition to three family-based sessions. Epstein and colleagues have shown that family-based lifestyle change, including the incorporation of exercise into daily living (Epstein, Wang, Koeske & Vaolski, 1985), decreasing sedentary behaviors (Epstein, Paluch, Gordy, & Dorn, 2000), and dietary changes (Epstein et al., 2001) promote greater decreases in percent overweight in children.

The primary hypotheses were: At session 8, adolescents receiving PASCET-PI-2 will demonstrate significant weight loss and will have significantly reduced depressive symptoms as measured by a calibrated SECA scale and the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI), respectively. Exploratory outcome measures consisted of: (a) body mass index (BMI) percentile to measure weight to height ratio adjusted for sex and age (Center for Disease Control, 2007); (b) the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life (IWQoL; Kolotkin et al., 2006) to measure the impact of health or disease on physical, mental, and social well-being from the patient's perspective; and (c) the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (Chervin, 2000) to measure sleep disturbances.

Methods

Participants

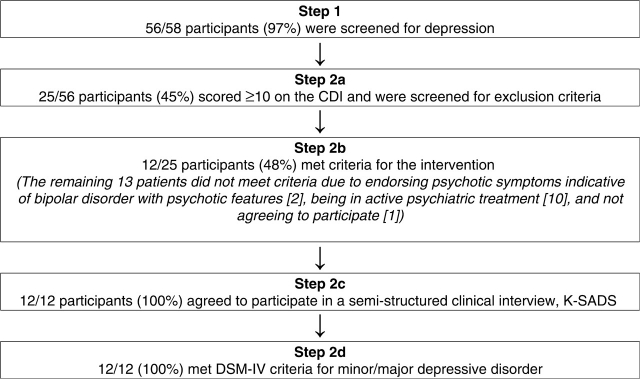

This study was conducted through the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Center at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh and was approved by the University's Institutional Review Board. Informed assent and consent were obtained. Participants, ages 12–18, were English-speaking patients with PCOS confirmed by a board-certified endocrinologist based on clinical and laboratory evidence of hyperandrogenism (Arslanian et al., 2002; Warren-Ulanch & Arslanian, 2006). Participants were seen during routine medical appointments and were approached about recruitment by their endocrinologist and/or a research coordinator. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the selection of patients to participate involved a two-step screening process similar to previous studies investigating emotional health in physically ill children (Szigethy, 2004).

Figure 1.

Screening process for adolescents with PCOS.

Exclusion criteria consisted of: The presence of bipolar or psychotic disorders, antidepressant medication within 3 weeks, suicidal/homicidal plan requiring immediate psychiatric hospitalization, and current empirically validated psychotherapy from another provider. If patients were willing to discontinue treatment with their current therapists and met criteria for current depression, they were included in the study.

Intervention

The PASCET-PI addresses primary control, secondary control, coping mechanisms, and three family-based sessions (Beardslee, Gladstone, Wright, & Cooper, 2003; Szigethy et al., 2004). While up to 60% of the sessions were permitted to be done by phone instead of in-person to decrease participant burden, in our sample only two sessions were done by phone for two participants. Eight individual 45–60 min sessions were conducted weekly, and participants were given the option of coming to the PCOS Center or receiving the intervention at a satellite location. Individual sessions focused on topics such as the comorbidity between physical illness and depression; scheduling behaviorally activating events; and engaging in positive thinking and cognitive restructuring. The session content can be found in Tables I and II.

Table I.

Outline of Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training for Adolescents with POCS

| Session | Weigh-ins; 45–60 min of manualized treatment; 20 min of physical activity |

|---|---|

| 1 | Psychoeducation about comorbid depression and physical illness, CBT, and problem-solving approaches; incorporation of lifestyle change determined by adolescent; and difference between dieting and lifestyle change |

| 2 | Constructing physical illness narrative; applying the problem-solving approach to illness coping and lifestyle barriers, assess impact of sleep disturbances; logging food and physical activity; reading food labels; and avoiding food traps |

| 3 | Choosing enjoyable solo activities (physical activity); planning social activities; developing social problem-solving skills; resetting lifestyle goals (nutrition and exercise); avoiding sneak eating; and psychological vs. physiological hunger |

| 4 | Relaxation techniques; choosing 2–3 behaviorally activating events; planning ahead for healthy meals, special occasions, and eating out |

| 5 | Showing positive self; developing talents; body image development; re-assess lifestyle goals; staying motivated; increasing physical activity; everyday lifestyle movement; and decreasing sedentary behavior |

| 6 | Identifying negative cognitive distortions; review body image diary; review sleep; and developing a health body image and self-esteem |

| 7 | Modifying negative cognitive distortions and attributions regarding health, emotions, and physical self; coping with barriers (teasing, bullying, and moodiness) |

| 8 | Practicing positive reframing using thoughts, distracting activities, and social support; review of skills; staying on track; avoiding making lapses turn into relapses; and discussing booster session schedule |

Table II.

Outline of Family Sessions for Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training for Adolescents with PCOS

| Session | Family description (60–min session at baseline, Session 4, and Session 8) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Probe family's illness experience; psychoeducation about depression and physical illness within family's illness narrative; and teach family problem solving |

| 4 | Psychoeducation about expressed emotion; discussion between adolescent and parents about progress and problems; and family game aimed at decreasing expressed emotion |

| 8 | Discussion between adolescent and parents about progress and problems; psychoeducation about early signs of depression; validation of grieving process and make meaning of physical illness-related adversity; and empowering parent–dolescent dyads or triads to reinforce PASCET skills in their daily lives |

At the beginning of each session, participants were weighed-in by a nurse or medical assistant (if the participant came to the clinic) or by a therapist (if the intervention was done within the community). These weights were tracked using a weight graph that was reviewed at the beginning of each session. Any in-between session assignments were then returned to the adolescent/her family with feedback before the session started. Study nutritionists provided feedback on food logs and follow-up questions were answered either by the interventionist, or by the nutritionist/exercise physiologist depending on the content of the query. Subsequently, the 30–45 min manualized treatment was delivered and each session ended with 15–20 min of physical activity. If the session was done within the clinic, an exercise physiologist or guest (yoga instructor, local swim coach, climbing wall supervisor) conducted the physical activity portion of the session. In addition to the eight individual sessions, three family-based sessions focusing on the family's illness experience, the child's ability to need share, and the maintenance of positive thinking were conducted on the same date as the participant's baseline, session 4, and session 8 sessions, respectively. All manualized treatment portions of the sessions were conducted by the first author (D.L.R.), a clinical psychologist trained in CBT for weight loss; assessments were completed by the first author (D.L.R.) and were double-coded by a blind assessor.

Measures

Primary Outcome Variables

Weight. Weight was measured on calibrated SECA scales and height was measured on a SECA stadiometer by a Trained nurse or medical assistant within the Center. Adolescents wore medical gowns when being weighed at each session and removed shoes.

Depressive Symptoms

The Children's Depression Inventory child report (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) and parent report (CDI-P; Kovacs, 1992) assessed depressive symptomatology for primary outcome and screening purposes during the screening session, baseline, session 4, and session 8. A cut-off of ≥10 from either the CDI or CDI-P was chosen to qualify for a more thorough clinical interview. If the parent's score was equal to or higher than 10 and the child scored lower, the child was given the option to participate in the clinical diagnostic interview at Part 2. This cut-off score was chosen as it is consistent with sub-clinical levels of depression that are not solely from neurovegetative symptoms in physically ill youth (Szigethy et al., 2007); it is consistent with an adjustment disorder; and because it still provided an adequate range of scores to detect improvement in our preliminary work. The CDI has well-validated psychometric properties and has been used to reliably diagnose depression in medically ill populations (Seigel et al., 1990). This measure has high levels of internal consistency, test–retest reliability, concurrent, and predictive validity in the proposed age group (Lalongo, Edelsohn, & Kellam, 2001). Additional work has suggested that the CDI and CDI-P have adequate construct (Worchel et al., 1990) and discriminate validity (Ramano & Nelson, 1988). The range of CDI scores for the current investigation was 10–41; internal consistency coefficients ranged from .78 to .91.

Based on Item 9 on the CDI (i.e., I do not think about killing myself; I think about killing myself but I would not do it; I want to kill myself), careful discussions with both the parent(s) and adolescents who exhibited suicidal thoughts or intentions, or who indicated engaging in self-injurious behavior, were conducted. Suicidal intent, plans, and means were evaluated by a licensed mental health provider. If at any point during the study the adolescent had a suicide plan or attempt, or if the severity of the adolescent's depression required hospitalization, hospitalization was facilitated. If the subject required additional care but not hospitalization, the research team facilitated the subject's obtaining this care. One adolescent expressed suicidal ideation during the study and paged the first author (D.L.R.) who was able to see the adolescent that day.

Psychiatric Diagnosis

The Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman. Birmaher, Brent, & Rao, 1997) assessed current and past psychiatric diagnoses based on information collected from interviewing both the adolescent and the parent. Agreement is reached between child and parent for scoring purposes. This instrument was utilized for confirming a diagnosis of minor or major depression after the screening appointment, and will be utilized as a categorical outcome variable in future studies. Inter-rater and test, retest reliability have been established, as well as convergent and discriminant validity (Gammon et al., 1983).

Secondary Outcome Variables

BMI percentile (Center for Disease Control, 2007) was calculated for age and gender using EpiInfo's NutStat program. This measure was used because it can decrease if adolescents grow concomitantly of weight gain.

Exploratory Outcome Variables

Health-related Quality of Life

Impact of Weight on Quality of Life Questionnaire—Kids (IWQoL-K; Kolotkin et al., 2006) documents quality of life related to being overweight in children. This 27-item questionnaire contains questions that cover the domains of Physical Comfort, Body Esteem, Social Life, and Family Relations. Kolotkin et al. (2006) provided support for the measure's strong psychometric properties, discrimination among BMI groups and between clinical and community samples, and responsiveness to weight loss. Psychometric properties in the current sample were strong and internal consistency was.92, similar to the validation sample.

Physical health measures were attained by trained medical staff within the PCOS Clinic. The following physical measures were taken as part of the clinical care of these participants and are presented here for exploratory purposes to examine the possible effect of PASCET-PI-2 on these outcomes. Baseline and follow-up results were available for blood pressure, percent fat mass, menstrual regularity, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Blood pressure was attained using a manual blood pressure monitor that consisted of a stethoscope and an inflatable arm cuff. The cuff was manually inflated by pumping the bulb and listening for arterial blood sounds, as well as heart rate monitoring. Trained medical staff within the Center completed these blood pressures and elevated scores were checked by a physician.

Body composition was measured by air-displacement plethysmography utilizing the BOD POD. The BOD POD is a system for measuring and tracking body fat and lean mass using patented air displacement technology. The BOD POD technology is based on the same whole-body measurement principle as hydrostatic weighing (the “dunk tank”).

Waist circumference was measured in duplicate, midway between the lowest rib and the superior border of the iliac crest, with a flexible tape. The average of the two measurements was used.

Menstrual regularity was assessed via self- and parental-report at baseline, session 4, and session 8. Adolescents kept a calendar of their menstrual cycle and brought it with them to each session.

The Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ; Chervin, 2000) was used as a screener for sleep-related breathing disorder. This scale has been validated in children with a score of 5 or less indicative of improbable sleep-related breathing disorder and a score of 8 or more indicative of possible sleep-related breathing disorder (note: an appropriate referral for a sleep study or to pulmonology was completed for corresponding participants). The scales showed good internal consistency (.86) and, in the same sample, good test–retest stability. All secondary outcome variables were collected at baseline, session 4, and session 8.

Statistical Analyses

Paired sample t-tests were used to assess differences between pre-and post-treatment continuous variables. One-tailed significance tests were conducted as hypotheses were directional. All variables met assumptions for parametric tests. Eta-squared statistics are reported with each analysis to indicate effect size. For the current investigation, Cohen's (1988) definition for small (.01), moderate (.06), and large (.14) effect sizes will be utilized.

Results

Description of the Sample

As shown in Fig. 1, of 58 adolescents with PCOS who were approached, 56 agreed to be screened for the study and 25 had a score of ≥10 on the CDI or CDI-P (CDI range 10–41; M = 11.1, SD = 9.2). Of these 25, 12 qualified for the study.

Subjects were 12 females with obesity (BMI percentile range 97–99; M = 99, SD = .08) and a mean age of 15.7 ± 1.8 years. Seven patients identified themselves as Caucasian, three as African American, one as Native American, and one as Middle Eastern. Nine adolescents lived in single-parent households and three in two-parent families. Annual family income ranged from $10,000 to >$90,000.

Primary Outcomes

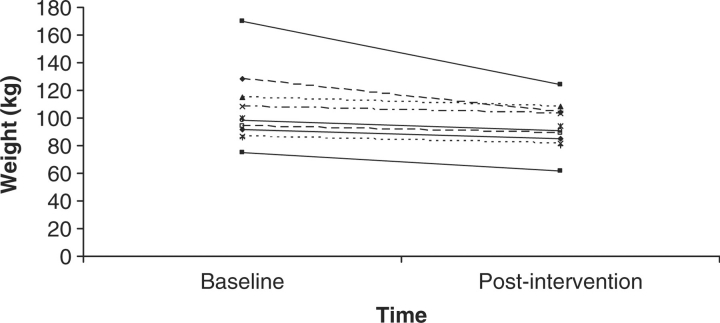

Weight showed a significant decrease across the 3 months from an average of 104 kg (SD = 26) to an average of 93 kg (SD = 18), t(11) = 6.6, p < .05. Figure 2 shows that one participant lost 48 kg, but that all participants lost at least some weight and none gained weight during the intervention. This resulted in an effect size of .45 for weight.

Figure 2.

Weight in kilograms at baseline and postintervention for all 12 participants.

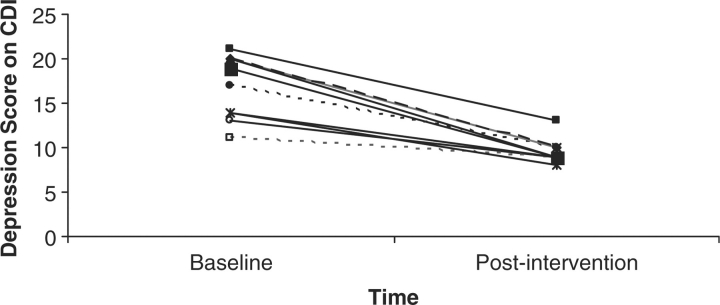

Depressive symptoms on the CDI significantly decreased from a mean of 17 (SD = 3) to a mean of 9.6 (SD = 2), t(11) = 16.8, p < .01, across the 3 months of the intervention. As seen in Fig. 3, this decrease was the result of all participants experiencing a decrease in the number of depressive symptoms, not as a result of outliers bringing down the mean. Baseline depression symptoms were also assessed by parent report (CDI-P; M = 16, SD = .9), and were highly correlated to child report, r = .89, p < .01. This resulted in an effect size of .81 for depressive symptoms by child report.

Figure 3.

Number of depressive symptoms on the CDI at baseline and posttreatment for all 12 participants.

Secondary and Exploratory Measures

Additional data focusing on BMI, the overall health-related quality of life and physical functioning of the adolescents were also collected. First, adolescents' BMI improved from a mean of 39 (SD = 9) to a mean of 35 (SD = 6), t(11) = 6, p < .05. Second, the adolescents reported that their overall health-related quality of life improved from a mean of 77 (SD = 20) to a mean of 82 (SD = 27), t(11) = −1, p < .05. Third, menstrual regularity improved from a mean of 0 (i.e., no adolescents had regular cycles) to a mean of 1 (i.e., menstrual regularity was achieved for all 12 participants), t(11) = −1, p < .05. Last, sleep-related breathing improved from a mean of 35 (SD = 5) to a mean of 30 (SD = 2), t(11) = 1, p < .05. T-tests for BMI, global health-related quality of life, menstrual regularity and sleep-related breathing were statistically significant; however, due to the small sample size and large standard deviations, all pre- and post-scores are provided and should be interpreted with caution. Percent body fat improved from a mean of 42 (SD = 7) to a mean of 38 (SD = 11); waist circumference improved from a mean of 98 (SD = 17) to a mean of 92 (SD = 14); and blood pressure improved form a mean of 115 (SD = 7) to a mean of 110 (SD = 11); t(11) = 0, p = NS. However, despite the promising improvements, these changes were not statistically significant.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that a manual-based CBT approach modified for adolescents with PCOS is feasible and promising. The PASCET-PI-2 showed promising effects with significant reductions in obesity and depression. Also of note are the decreased rates of physiological comorbidities such as menstrual irregularity; high percent of fat mass, blood pressure, and sleep-related breathing disorder; and mid-region adiposity associated with PCOS. Moreover, the distinct types of depression that the adolescents endorsed are noteworthy and consist of severe irritability with excessive anhedonia and suicidal ideations.

This work is novel in that it targets interrelated regulatory systems: Eating, physical activity, and mood during a key neuromaturational interval—adolescence. Adolescence serves as a crucial time in the development of regulatory processes as well as a critical interval for eliciting autonomous motivational systems. Adolescents are able to develop habits, skills, and proclivities in each domain which serve as a set of synerginistic self-regulatory processes.

There are many ways that PASCET-PI-2 can be helpful for pediatric patients. First, utilizing PASCET-PI-2 to reduce physical (obesity) and emotional (depression) disturbances in adolescents who have PCOS represents an innovative treatment for physical health-related disturbances. Second, the PASCET-PI-2 specifically focuses on physical illness narratives, motivational concepts, healthy lifestyle goals, and family-based change—all skills that have the potential to help these adolescents long after intervention completion. Finally, a nonpharmacological treatment is integrated into the adolescent's medical system of care to minimize stigma and ease treatment.

This was an open trial subject to no time- and attention-control group, so results should be considered preliminary. Additionally, only one therapist provided treatment, limiting potential generalizability of findings. However, κ reliability coefficients of blinded psychology interns who observed the assessments had sound psychometric properties, κ = .87. In addition, the improvements in weight and depression might be attributable to greater attention from health care providers, typical fluctuation of symptoms, heightened social desirability from the adolescents, or greater self-monitoring of weight status and emotional symptoms. Additional data on parental ratings of depression at intervention completion would also be informative.

The improvements in adolescents’ physical health suggest a positive psychological effect that may buffer later physical illness stressors. A larger sample size may be needed to assess PASCET-PI-2's effectiveness in reducing PCOS-related pathophysiology. Finally, the short-term nature of the study precludes assessment of long-term outcomes. Previous CBT studies have shown that depression relapse is high in adolescents with physical illness (Clark, Rohde, Lewinsohn, Hops, & Seeley, 1999); however, similar approaches with physically ill children have shown preliminary long-term effectiveness (Szigethy et al., 2007).

These results represent encouraging preliminary data in the development of a promising manual-based CBT approach to treat depression and obesity in adolescents with PCOS. This study lays the groundwork for future randomized comparison studies assessing the effectiveness of CBT in treating obesity and depression in adolescents. Further research such as focus groups on what participants found most helpful, would be beneficial in developing the intervention. Future directions will also investigate underlying mechanistic explanations for change such as endocrine pathways (insulin resistance, glucose, and inflammatory factors) and utilize more ecologically valid measures (wearable monitors that document energy and calorie expenditure and frequent mood-monitoring phone calls) to track mood, eating, and physical activity within the adolescents’ environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the dedicated assistance of Stefanie Weiss, Psychology Research Fellow, University of Michigan and Nichole Travis and Megan Barna, Research Assistants, University of Pittsburgh. We would also like to thank the providers at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Center (Dr Tamara Hannon, Dr Fida Bacha, Dr Julia Warren-Ulanch, Marci DeLeo, Sharon Crow, John Weidinger, Jill Landsbaugh, Megan McQuaide, and Vanessa Weisbrod).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Arslanian SA, Lewy V, Danadian K, Saad R. Metformin therapy in obese adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome and impaired glucose tolerance: Amelioration of exaggerated adrenal response to adrenocorticotropin with reduction of insulinemia/insulin resistance. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2002;87:1555–1559. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslanian SA, Witchel SF. Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents: Is there an epidemic? Current Opinion in Endocrinology and Diabetes. 2002;9:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, Wright EJ, Cooper AB. A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: Evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics. 2003;112:119–131. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services. BMI—body mass index: About BMI for children and teens. 2007. Retrieved February 1, 2007 from http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/bmi/childrens_BMI/about_childrens_BMI.htm.

- Chervin RD, Hedger KM, Dillon JE, Pituch KJ. Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): Validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems. Sleep Medicine. 2000;1:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(99)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GN, Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Seeley JR. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of adolescents with depression: Efficacy of acute group treatment and booster sessions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:272–279. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obesity Research. 2001;9:171–178. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Myers MD, Raynor HA, Saelens BE. Treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics. 1998;101:554–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Gordy CC, Dorn J. Decreasing sedentary behaviors in treating pediatric obesity. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154:220–226. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein L, Squires S. The stoplight for chlildren: An 8-week program for parents and children. Boston, MA: Little Brown & Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Wing RR, Koeske R, Valoski A. A comparison of lifestyle exercise, aerobic exercise, and calisthenics on weight loss in obese children. Behaviour Therapy. 1985;16:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Food Standards Agency. The balance of good health: Information for educators and communicators. London: Center for Disease Control; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gammon G, John K, Rothblum E, Mullen K, Tischler G, Weissman M. Use of a structured diagnostic interview to identify bipolar disorder in adolescent inpatients: Frequency and manifestations of the disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140:543–547. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.5.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelein MJ, Thatcher SS. Depression and body image among women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11:613–625. doi: 10.1177/1359105306065021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeger KM. Role of lifestyle modification in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;20:293–310. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinrake E, Abreu A, Maifeld M, Van Voorhis BJ, Dokras A. Increased risk of depressive disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2007;87:1369–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children- present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy for Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolotkin RL, Zeller M, Modi AC, Samsa GP, Polanichka QN, Yanovski JA, et al. Assessing weight-related quality of life in adolescents. Obesity. 2006;14:448–457. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. New York: Multi-health Systems; 1992. Children's depression inventory manual. [Google Scholar]

- Lalongo NS, Edelsohn G, Kellam SG. A further look at the prognostic power of young children's reports of depressed mood and feelings. Child Development. 2001;72:736–747. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lernmark B, Persson B, Fisher L, Rydelius P. Symptoms of depression are important to psychological adaptation and metabolic control in children with diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine. 1999;16:14–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Contrada RJ. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: A perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychology and Health. 1998;13:717–733. [Google Scholar]

- Ramano BA, Nelson RO. Discriminant and concurrent validity of measures of children's depression. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1988;17:255–259. [Google Scholar]

- Rasgon NL, Rao RC, Hwan S, Altshuler LL, Elman S, Zuckerbrow-Miller J, et al. Depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Clinical and biochemical correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;74:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rofey DL, Warren-Ulanch J, Noll R, Szigethy E, Weisbrod V, Van Schaick K, et al. Reducing depressive symptoms in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Boston, MA: Presentation at the North American Association for the Study of Obesity; 2007. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Seigel W, Golden N, Gough J, Lashley M, Sacker IM. Depression, self-esteem, and life events in adolescents with chronic diseases. Journal of Adolescent Health Care. 1990;11:501–504. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(90)90110-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: The skinny on interventions that work. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:667–691. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szigethy E, Carpenter J, Baum E, Kenney E, Baptista-Neto L, Beardslee W, et al. Case study: Longitudinal treatment of adolescents with depression and inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:396–400. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000198591.45949.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szigethy E, Hardy D, Kenney E, Kiska R, Keljo D, David D, Robert N. Longitudinal effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for depressed adolescents with IBD. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2007;13:673–674. [Google Scholar]

- Szigethy E, Whitton SW, Levy-Warren A, DeMaso DR, Weisz J, Beardslee WR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: A pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:1469–1477. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000142284.10574.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T, Glanville J, Hayden CJ, While D, Barth JH, Balen AH. Combined lifestyle modification and metformin in obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind multicentre study. Human Reproduction. 2006;21:80–89. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent M, Austin SB, Rich M, Gordon CM. Overweight status of adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome: Body mass index as mediatory of quality of life. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2005;5:107–111. doi: 10.1367/A04-130R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walco GA, Ilowite NT. Cognitive-behavioral intervention for juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Journal of Rheumatology. 1992;19(10):1617–1619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren-Ulanch J, Arslanian S. Treatment of PCOS in adolescence. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;20:11–30. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner CL, Primeau M, Ehrmann DA. Androgens and mood dysfunction in women: Comparison of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome to healthy controls. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:356–362. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127871.46309.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worchel FF, Hughes JN, Hall BM, Stanton SB, Stanton H, Little VZ. Evaluation of subclinical depression in children using self-, peer-, and teacher report measures. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:271–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00916565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz BO, Knochenhauer ES, Azziz R. Impact of obesity on the risk for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;98:162–168. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]