Abstract

Objective Examine relationships between parental depressive symptoms, affective and instrumental parenting practices, youth depressive symptoms and glycemic control in a diverse, urban sample of adolescents with diabetes. Methods Sixty-one parents and youth aged 10–17 completed self-report questionnaires. HbA1c assays were obtained to assess metabolic control. Path analysis was used to test a model where parenting variables mediated the relationship between parental and youth depressive symptoms and had effects on metabolic control. Results Parental depressive symptoms had a significant indirect effect on youth depressive symptoms through parental involvement. Youth depressive symptoms were significantly related to metabolic control. While instrumental aspects of parenting such as monitoring or discipline were unrelated to youth depressive symptoms, parental depression had a significant indirect effect on metabolic control through parental monitoring. Conclusions The presence of parental depressive symptoms influences both youth depression and poor metabolic control through problematic parenting practices such as low involvement and monitoring.

Keywords: diabetes, depression, metabolic control, parental depression, parental monitoring

Depression in children and adolescents is associated with significant impairments in both current psychosocial functioning and functioning in adulthood (Harrington, Fudge, Rutter, Pickles, & Hill, 1990; Kandel & Davies, 1986; Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley, Klein, & Gotlib, 2003). Youth with type 1 diabetes appear to be at particularly high risk for depression (Dantzer, Swendsen, Maurice-Tison, & Salamon; 2003; Kovacs, Goldston, Obrosky, & Bonar, 1997), with rates ranging from 17% (Massengale, 2005) to 20% (Grey, Whittemore, & Tamborlane, 2002) as compared to general population rates of 0.4–8.3% (Mash & Wolfe, 2007). Depression in youth with type 1 diabetes is of particular concern in light of the known links between depression, poor metabolic control (Grey et al., 2002; La Greca, Swales, Klemp, Madigan, & Skyler, 1995; Leonard, Jang, Savik, Plumbo, & Christensen, 2002; Lernmark, Persson, Fishert, & Rydelius, 1999), increased risk for hospitalizations due to medication non-compliance (Garrison, Katon & Richardson, 2005; Liss et al., 1998; Stewart, Rao, Emslie, Klein, & White; 2005), and, for females, treatment adherence (Korbel, Wiebe, Berg, & Palmer, 2007).

Childhood depression emerges in the context of the family (Hammen, 1991). Such relationships are due in part to the well known relationship between child depression and caregiver depression (Racusin & Kaslow, 2004). The general consensus is that parental depression increases the risk for child depression (Beardslee, Versage, & Gladstone, 1998; Beck, 1999; Downey & Coyne, 1990; Elgar, McGrath, Waschbusch, Stewart, & Curtis, 2004; Kane & Garber, 2004; LaRoche, 1989; Phares & Compas, 1992). Although research on depression in parents of youth with type 1 diabetes is more limited, studies have suggested that higher levels of parenting stress in mothers are associated with increased rates of youth internalizing problems (Lewin et al., 2005) and depressive symptoms (Mullins et al., 2004).

One mechanism by which parental depression affects the child is through its influence on parenting behavior (Cummings & Davies, 1994). Parenting behaviors that have been widely explored in community samples of youth include instrumental aspects of parenting, such as discipline, limit setting and parental monitoring, and affective aspects of parenting such as warmth, support, and psychological control. Compared to parents with no psychiatric diagnosis, depressed parents have been found to display more hostile/critical, negative, rejecting, and unsupportive behavior (Burbach & Borduin, 1986; Kaslow, Deering, & Racusin, 1994; McCauley & Myers, 1992; Sheppard, 1994), and to struggle to effectively discipline and manage their child's behavior (Cummings & Davies, 1994; Downey & Coyne, 1990; Kaslow et al., 1994). However, although depressed parents may display poor parenting skills in both instrumental and affective domains, it is low warmth and high levels of parental criticism or intrusion in particular that have been found to directly influence depressive symptoms in the general population of youth (Barber, Stolz, & Olsen, 2005; Gray & Steinberg, 1999).

For youth with diabetes, the knowledge base regarding the relationship between parenting behaviors and youth depression and health outcomes, as well as factors that influence parenting behaviors, is relatively limited. Using a sample of young children, Davis et al. (2001) found that high parental warmth was associated with better adherence while high parental restrictiveness was associated with poorer metabolic control. In an adolescent sample, Butler, Skinner, Gelfand, Berg, & Wiebe (2007) found that a maternal parenting style characterized as controlling, intrusive, and rejecting, was associated with higher levels of depression in youth but that parenting variables did not predict regimen adherence behavior. Ellis et al. (2007) found that high levels of parental supervision and monitoring were directly related to higher youth regimen adherence and indirectly related to better glycemic control. However, neither of these studies investigated the relationship between parental depression and parenting style nor the influence of these factors on both mental health (youth depression) and physical health status (glycemic control) simultaneously. In addition, at least two of the studies investigated parenting style in samples that were primarily white and/or middle class. Therefore the applicability of findings to minority or low income samples of youth with diabetes, for whom higher rates of depression are typically documented (Roberts, Roberts, & Chen, 1997; Rushton, Forcier, & Schectman, 2002), is largely unknown.

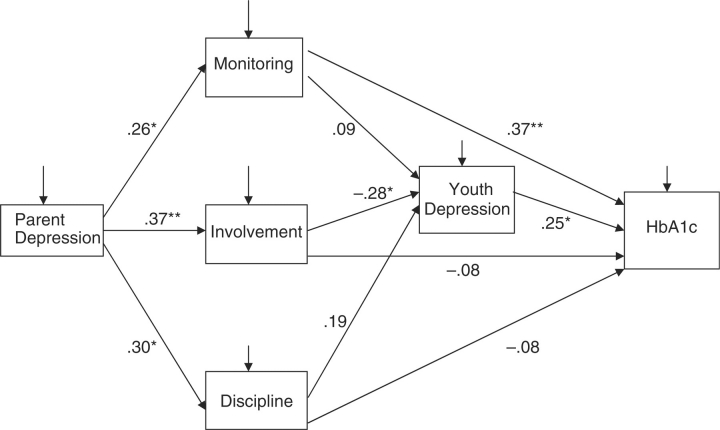

The purpose of the present study was to (a) further investigate relationships between affective (i.e., warmth) and instrumental (e.g., monitoring and discipline) parenting practices, youth depressive symptoms and glycemic control in a diverse, urban sample of adolescents with diabetes and (b) determine whether parental depressive symptoms would be related to problematic parenting practices in a chronic illness sample. In light of findings from prior studies on the effect of parenting on youth depression, the primary hypothesis was that parenting variables would mediate the relationship between parental depressive symptoms and youth depressive symptoms. Given the considerable literature regarding links between low levels of parental warmth and youth depressive symptoms in the broader child psychopathology literature, we hypothesized that low warmth, but not poor monitoring or inconsistent discipline, would be related to higher levels of youth depressive symptoms. A secondary hypothesis was that parenting variables would have both direct effects on metabolic control and indirect effects on metabolic control via youth depressive symptoms. Figure 1 shows the theoretical model that operationalizes these hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of relationships between parental depressive symptoms, parenting variables youth depressive symptoms and metabolic control.

Methods

Participants

Youth and their primary caregivers were participants in a larger clinical trial investigating the effectiveness of intensive, home-based psychotherapy for improving regimen adherence in youth with diabetes in chronically poorly metabolic control. Data used in the present analyses were drawn from the participant's baseline data collection prior to study randomization or receipt of any intervention.

In order to be eligible for the parent study, participants had to be between 10 and 18 years of age, have a diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes for at least one year that required management with insulin, have a current HbA1C of 8% or higher and a mean HbA1c of 8% or higher during the year before study entry, and be residing in a home setting (e.g., not in residential treatment). No child psychiatric diagnoses were exclusionary with the exception of moderate or severe mental retardation, and psychosis. Families were also excluded if they were not English speaking or could not complete study measures in English. Potential participants were initially approached in person by medical staff at the time of a regularly scheduled visit to a university-affiliated pediatric diabetes clinic or during an inpatient hospitalization. This was followed up by contacts from study research staff and home-based consent visits if families indicated an interest in participating. Ninety percent of eligible families agreed to participate. The final sample consisted of 61 adolescents and their primary caregivers. The research was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of the university affiliated with the hospital where the adolescents were seen for medical care. All participants provided informed consent and assent to participate.

Demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table I. The average age of adolescents participating in the study was 14.3 years. Of the 61 participants, 62% were female. Eighty-seven percent were African-American, 10% were white, and the rest were of other race/ethnicity. Mean family income was $39,831. Seventy percent of adolescents resided in two parent families, which included two biological parents, a biological parent and step-parent and single parents living with a partner, and 30% resided in single parent families. Ninety-two percent of caregivers participating in the study were female and 97% were the biological parent of the child. 85% had type 1 diabetes. There were no significant differences between type 1 and type 2 children with regard to HbA1c level, duration of diabetes, and total dose of insulin per day. Overall, the demographics of the sample were representative of the diverse, urban population served by the clinic where subjects were recruited. Youth had been diagnosed with diabetes for an average of 4.6 years at the time of study entry. Mean hemoglobin A1c was 11.78%, suggesting that the sample was in poor metabolic control, as expected.

Table I.

Demographics and Characteristics of Adolescents and Their Families (N = 61)

| Percentage | M (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Age | 14.35 (2.2) | 10.15–18.01 | |

| Annual Family Income (dollars) | $39,831 (2.9) | $10,000–100,000 | |

| Child gender | |||

| Male | 38 | ||

| Female | 62 | ||

| Number of parents in home | |||

| Two parentsa | 70 | ||

| Single Parent | 30 | ||

| Participating caregivers | |||

| Biological parent | 97 | ||

| Maternal caregiver | 92 | ||

| Child ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 10 | ||

| African-American | 87 | ||

| Other | 3 | ||

| Duration of diabetes in years | 4.42 (2.8) | 0.48–15.06 | |

| Diabetes type | |||

| Type 1 | 85 | ||

| Type 2 | 15 | ||

| HbA1c | 11.78 (2.4) | 8.0–17.7 |

aTwo parents included two biological parents, a biological parent and a step-parent or a biological parent living with a partner.

Procedure

All measures were collected by a trained research assistant in the participants’ homes. Both the youth and the primary caregiver completed questionnaires. Families were provided $50 to compensate them for participating in the data collection session.

Measures

Adolescent depressive symptoms were measured by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), completed by the parents and youth, respectively. The CBCL and the YSR yield T-scores for eight narrow-band syndrome scales (Anxious-Depressed, Withdrawn-Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Attention Problems, Thought Problems, Social Problems, Aggressive Behavior, and Rule-Breaking Behavior), two broad-band second-order syndrome scales (Internalizing and Externalizing), and a Total Problems scale. Because prior research with chronically ill children suggests that the broad-band internalizing scale may inflate depressive symptoms due to the inclusion of physical symptoms (Drotar, Stein & Perrin, 1995), the narrow-band Withdrawn/Depressed subscale was used in the present analyses. The CBCL and YSR T-scores of 65 or higher are within the clinical range and scores between 60 and 64 are within the sub-clinical range. Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. The CBCL and YSR have extensive reliability and validity data and have been used with various populations of children, including children with chronic illness. To ensure comparability across youth of different ages and genders, T-scores rather than raw scores were used.

Parental depressive symptoms were measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI 18; Derogatis, 2004), an abbreviated version of the BSI instrument that was designed to assess psychological status in persons over 18 years of age. The BSI 18 measures three primary symptom dimensions: Somatization, depression, and anxiety. The depression subscale was used in the present analyses; the clinical cut-off score for this measure is 65. Higher scores on the BSI 18 indicate more depressive symptoms. Internal consistency for the current sample was 0.84.

Parenting skills were measured by the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Shelton, Frick, & Wootton, 1996). The APQ is a widely used, self-report instrument that measures multiple parenting constructs. Internal consistency for all scales is moderate to high (Shelton et al., 1996) and test-retest reliability across a 3-year interval is adequate (McMahon et al., 1997). Diabetes-specific measures were not used because no such measures with adequate psychometrics are currently available to measure warmth or limit-setting; furthermore, we intended to measure general parenting behavior rather than parenting specific to diabetes-care tasks. Initial reliability and validity were reported with 6- to 13-year old youth. However, the APQ has also been used been with adolescent populations (Wootton, Frick, Shelton, & Silverthorn, 1997) as well as with chronically ill youth (Tompkins & Wyatt, 2008). Five scales can be derived from the instrument: use of corporal punishment, inconsistent discipline, poor monitoring, involvement, and clarity of rules and expectations. The APQ “involvement” scale measures warmth of the relationship between the youth and parent, that is, strength of the affective bond, rather than other related constructs such as parental instrumental support or help. Therefore, for the purpose of the present study, the scales that were closest to the constructs of interest were poor monitoring (e.g., “You don't check that your child comes home from school when s/he is supposed to”), involvement (e.g., “You hug or kiss your child when s/he has done something well”), and inconsistent discipline (e.g., “You threaten to punish your child and then do not actually punish him/her”). Higher scores on these scales reflect more involvement (warmth), less supervision and monitoring and less effective discipline. Internal consistency for the current sample for these three scales was 0.81, 0.51 and 0.65, respectively.

Metabolic control was calculated using hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a retrospective measure of average blood glucose during the past 2–3 months. Typical HbA1C for a person without diabetes is between 4 and 6%; the target range for adolescents with diabetes is less than 7.5% (Silverstein et al., 2005). Values were obtained using the Accubase A1c test kit, which is FDA approved. The test uses a capillary tube blood collection method instead of venipuncture and is therefore suitable for home-based data collection.

Results

Bivariate analyses were conducted to assess simple relationships between variables. The hypotheses that parenting variables (particularly parental involvement/warmth) would fully mediate the relationship between parental depressive symptoms and child depressive symptoms and that parenting variables would have both direct effects on metabolic control and indirect effects on metabolic control via child depressive symptoms were evaluated via structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS Version 7.0. The theoretical model is shown in Figure 1.

Because only parent report was available for the parent depressive symptoms and parenting style variables, models were evaluated using path analysis, a form of SEM that uses all single indicator constructs. Path analysis is similar to ordinary least squares regression but retains the advantage of allowing both the assessment of goodness of fit of a specified model and testing of each estimated path coefficient. In the case of child depression, both parent and child reports were available and used in the analyses.

Bivariate Analyses

Consistent with other samples of youth with diabetes, a significant number of youth in the present sample had depressive symptoms in the clinical range (i.e., above a T-score of 65). Based on parent report on the CBCL, 20% of youth had clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms. Based on youth report on the YSR, 17% of youth fell in the clinical range. 10% of parents fell in the clinically significant range for depression on the BSI.

Bivariate analyses were conducted to test associations between variables (Table II). Parental depressive symptoms were significantly related to each parenting variable such that higher levels of parental depression were related to lower monitoring (r = 0.26, p < .05), inconsistent discipline (r = 0.31, p < .05) and lower parental involvement/warmth (r = −0.37, p < .01). However, of the three parenting variables, only monitoring was related to metabolic control with lower levels of monitoring associated with worse metabolic control (r = 0.42, p < .01). When youth depression was assessed by parent report, high levels of inconsistent discipline (r = 0.28, p < .05) and low involvement/warmth (r = −0.34, p < .05) were each significantly related to higher levels of youth depression. In addition, youth depressive symptoms were significantly related to metabolic control such that higher levels of depression were associated with poorer metabolic control (r = 0.35, p < .01). However when youth depression was assessed by youth report, youth depression was not significantly related either to parenting nor metabolic control. As youth reported depression was unrelated to either objective measures or questionnaire measures, path analyses to test study hypotheses were conducted with parent reported youth depression only.

Table II.

Correlations Among Psychosocial and Health Outcome Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BSI | |||||||

| 2. APQ-Mon | 0.26* | ||||||

| 3. APQ-Inv | −0.37** | −0.29** | |||||

| 4. APQ-Ind | 0.31* | .37** | −0.23 | ||||

| 5. CBCL Dep | 0.48** | 0.24+ | −0.34** | 0.28* | |||

| 6. YSR Dep | 0.27* | 0.19 | −0.24+ | 0.04 | .43** | ||

| 7. HbA1c | 0.26* | 0.42** | −0.25 | 0.14 | 0.35** | 0.21 | |

| Mean | 50.25 | 7.11 | 26.48 | 8.30 | 60.25 | 59.36 | 11.78 |

| SD | 9.55 | 4.46 | 6.82 | 4.08 | 10.59 | 8.04 | 2.44 |

| Minimum | 40.00 | 0.00 | 9.00 | 0.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 8.00 |

| Maximum | 74.00 | 18.00 | 38.00 | 17.00 | 89.00 | 82.00 | 17.70 |

Note. BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; APQ-Mon, Alabama Parenting Questionnaire Monitoring Subscale, higher scores reflect less monitoring; APQ-Inv, Alabama Parenting Questionnaire Involvement Subscale; APQ-Ind, Alabama Parenting Questionnaire Inconsistent Discipline Subscale, higher scores reflect less effective discipline; CBCL Dep, parent-reported depressive symptoms; YSR, youth-reported depressive symptoms; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

**p < .01, *p < .05.

Path Analyses

A structural equation model with all single indicator variables was fit to the variance/covariance matrix using a maximum likelihood solution to model relationships between variables. Initially, the theoretical model shown in Figure 1 was tested. The model had one exogenous variable (parental depression) and five endogenous variables (monitoring, discipline, involvement/warmth, youth depressive symptoms and metabolic control), with parental depressive symptoms having indirect effects on youth depressive symptoms through parenting variables and parenting variables having both direct effects on metabolic control and indirect effects through youth depressive symptoms. Three fit indices were evaluated: that the likelihood ratio χ2 test of model fit was non-significant, the comparative fit index (CFI) was >0.95, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was <0.08. Using these criteria, no fit index demonstrated adequate fit [X2(5, N = 61) = 18.66, p = .002; CFI = 0.73; RMSEA = 0.21] (Figure 2). Therefore, an alternative model was tested where all non-significant paths were trimmed. In addition, because the relationships between discipline and youth outcome variables were also non-significant, this variable was dropped from the alternative model. Examination of modification indices revealed a high covariance between error terms for child depressive symptoms and adult depressive symptoms, so they were allowed to covary. The model fit statistics for the trimmed model indicated excellent fit [X2(4, N = 61) = 2.80, p = .59 CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00].

Figure 2.

Full structural model. Standardized path coefficients are shown (*p < .05, **p < .01), with youth depression measured by parent report.

In this model (Figure 3), all paths were significant. Statistical tests of the indirect effect of parent depressive symptoms on youth depressive symptoms and parental depressive symptoms on metabolic control were performed using bootstrapped standard errors as recommended by Shrout & Bolger (2002). Parental depressive symptoms had significant indirect effects on youth depressive symptoms through involvement/warmth (standardized indirect effect = 0.136, p < .01). Youth depressive symptoms in turn were significantly related to metabolic control. Parental depressive symptoms also had a significant indirect effect on metabolic control through parental monitoring (standardized indirect effect = 0.13, p < .05); this path was independent of youth depression.

Figure 3.

Trimmed structural model predicting HbA1c from youth depressive symptoms, parenting variables and parental depressive symptoms. Standardized path coefficients are shown (*p < .05, **p < .01).

Discussion

The present study sought to clarify the relationship between affective (i.e., warmth) and instrumental (i.e., monitoring and discipline) parenting practices, youth depressive symptoms and glycemic control, and to determine whether depressive symptoms in parents were related to problematic parenting in a diverse, urban sample of adolescents with insulin-managed diabetes. Although there have been several recent studies pointing to the importance of parenting in understanding outcomes in youth with diabetes, risk factors for ineffective parenting practices in this population remain poorly understood. In particular, there is little information on the relationships between particular parenting difficulties and youth depression, which is important to the development of effective interventions. Moreover, there has been limited family research on minority youth with diabetes and how parenting practices or parental mental health may influence outcomes in this population.

Overall, rates of youth depression did not appear higher in this low income, predominantly minority sample than have been reported in samples of white, middle class youth with diabetes. Approximately 20% of youth fell in the at-risk range or above on measures of depressive symptoms. Given the high-risk contexts in which these youth resided, the fact that rates of depression are comparable to those of middle-class youth may attest to their resiliency. However, findings from the study suggest that adolescents who experienced higher levels of depressive symptoms also had significantly poorer metabolic control. These findings are consistent with the significant body of evidence documenting a relation between depression and poor metabolic control in youth with diabetes (e.g., Dantzer et al., 2003; Grey et al., 2002). Depression and poor metabolic control are likely to have bidirectional effects on one another. Youth with depression are unlikely to adequately complete their self-care, compounding inadequate glycemic control and poor metabolic control may exacerbate depression through increasing feelings of lethargy or fatigue. Depression is also particularly concerning when it presents in youth with diabetes due to its known association with hospitalizations for diabetic ketoacidosis (Garrison et al., 2005; Stewart et al., 2005), a dangerous and potentially life-threatening condition.

When parent-report of depressive symptoms was considered, higher levels of parental depressive symptoms were found to be associated with youth outcomes via two independent pathways. First, parental depressive symptoms were significantly associated with lower parental warmth towards the youth. In turn, lower warmth was associated with higher levels of youth depressive symptoms. Parental depressive symptoms were found to be associated with youth depressive symptoms through parental warmth. Although results from studies on general population samples of adolescents have documented the relation between depression in parents and low levels of parental involvement, support, and warmth (e.g., Barber et al., 2005; Kaslow et al., 1994), such relationships have not been documented within the diabetes population. The current study suggests that parenting behavior, specifically parental involvement and warmth, is one mechanism by which parental depression is associated with the development of depressive symptoms in youth with diabetes.

Second, parents with higher levels of depressive symptoms reported lower levels of parental monitoring and more inconsistent discipline. Such parenting styles were not related to youth depressive symptoms. However, low levels of monitoring by parents with more depressive symptoms were directly related to poorer metabolic control and low monitoring mediated the relationship between parental depressive symptoms and youth metabolic control. The association between low parental monitoring and poor metabolic control is supported by prior studies showing an association between monitoring and glycemic control (e.g., Ellis et al., 2007; Berg et al., 2008). Results from prior studies in general population samples of adolescents have not suggested strong associations between parental monitoring (high or low) and depression; rather, low parental monitoring and inconsistent discipline have frequently been shown to contribute to the development of aggression and conduct disorder (Barber et al., 2005). The present study did not evaluate externalizing behavior problems in youth, but it is possible that low monitoring and inconsistent discipline by parents could be associated with increased risk for such behavioral difficulties in youth with diabetes which in turn would be expected to be associated with risk for poor metabolic control (Leonard et al, 2002).

In the present study, study hypotheses were supported when parent report was used as the measure of youth depression. However, although the direction of findings was similar, youth-reported depression was not significantly related to either parenting variables or to HbA1c. Although such a finding may be accounted for by small sample size, it is more usual to find that youth report of internalizing symptoms is a better predictor of outcome. Parents in this sample also reported slightly higher rates of clinically significant youth depressive symptoms than did youth themselves, suggesting that youth may have been underreporting symptoms due to either social desirability factors or other reasons that are not known. Butner et al. (2009) found that greater discrepancies in reports between caregivers and adolescents were associated with poor management of diabetes and with mother's depressive symptoms which also suggests there may be greater potential for differences in perceptions when the caregiver is more depressed.

The current study suggests that parents of youth with diabetes with depressive symptoms are at risk for engaging in parenting behaviors that both directly and indirectly contribute to depressive symptoms and poor metabolic control in youth. Such findings suggest that there may be benefits to screening for parents at risk of depression as a way to prevent the development of health difficulties among youth with diabetes. In addition, interventions for youth depressive symptoms in this population may benefit from the inclusion of specific parenting interventions that focus upon improving the affective bond between the child and parent through increasing opportunities for positive interactions, problem solving, and targeting negative schemas and cognitions about the parent–youth relationship.

Study limitations include the fact that participants were drawn from the baseline sample of an intervention study targeting youth with poorly controlled diabetes. Hence, although overall recruitment rates into the study were high (90%), the sample may not be representative of youth with well controlled diabetes. Parenting style was assessed only from the parent's perspective and not from the youth's perspective. Previous studies have documented inconsistent agreement between caregivers and children on family experiences (Rutter & Sroufe, 2000) and future studies should include an assessment of the child's perspective on their parents’ parenting style. As the data were cross-sectional in nature, the potential reciprocal nature of the influences between parents and adolescents was not evaluated. For example, Kaslow et al. (1994) suggested that depressed youth also may influence parental mood by contributing to consistently negative parent-child interactions. Longitudinal studies are warranted to better understand such bi-directional relationships between youth and parent factors. The analyses relied primarily on self-report measures rather than objective ratings and internal consistency of some parenting scales was only moderate. Although in the present study parents appeared to be more accurate reporters than youth, other research has suggested that parents with depressive symptoms may over-estimate youth depressive symptoms (Hood, 2009). Replication of these findings using more comprehensive measures of depression is therefore warranted. Furthermore, the sample in this study was primarily minority and low income. Therefore, it is unclear whether findings might differ in a higher SES or White sample. Depression is also more common among females and older adolescents; however, the relatively small sample size precluded further analyses to determine whether the model was affected by age or gender. Similarly, separate analyses were not conducted for youth with type 1 vs. type 2 diabetes. Future studies may wish to further evaluate this, youth with type 2 diabetes are typically obese and youth obesity is associated with higher rates of depression.

In summary, the results of the present study provide empirical support for a model in which low parental involvement and warmth and low parental monitoring have adverse effects upon both mental and physical health outcomes in youth with diabetes. Parental depressive symptoms are likely to significantly increase the risk for such ineffective parenting styles and should be a focus of screening attempts for mental health professional when attempting to prevent the development of depressive symptoms and poor metabolic control in youth with diabetes.

Funding

Grant #R01 DK59067 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

References

- Achenbach TM, Racorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school aged form and profiles. Burlington, VT: ASEBA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Stolz HE, Olsen JA. Parental support, psychological control and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2005;70:1–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TRG. Children of affectively ill parents: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1134–1141. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. Maternal depression and child behaviour problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29:623–629. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, Butler JM, Osborn PM, King G, Palmer DL, Butner J, et al. Role of parental monitoring in understanding the benefits of parental acceptance on adolescent adherence and metabolic control of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:678–683. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino J, Galea S, Adams R, Ahern J, Resnick H, Vlahov D. Mental health service and medication use in New York City after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbach DJ, Borduin CM. Parent-child relations and the etiology of depression depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 1986;6:133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Butler JM, Skinner M, Gelfand D, Berg CA, Wiebe DJ. Maternal parenting style and adjustment in adolescents with type I diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:1227–1237. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butner J, Berg CA, Osborn P, Butler JM, Godri C, Fortenberri KT, et al. Parent-adolescent discrepancies in adolescents’ competence and the balance of adolescent autonomy and adolescent and parent well-being in the context of type 1 diabetes. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:835–840. doi: 10.1037/a0015363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist. 1998;53:221–241. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:73–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer C, Swendsen J, Maurice-Tison S, Salamon R. Anxiety and depression in juvenile diabetes: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:787–800. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CL, Delamater AM, Shaw KH, La Greca AM, Eidson MS, Perez-Rodrigez JE. Brief report: Parenting styles, regimen adherence, and glycemic control in 4- to 10- year-old children with diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26:123–129. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI 18 manual. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drotar D, Stein REK, Perrin EC. Methodological issues in using the child behavior checklist and its related instruments in clinical child psychology research. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24:184–192. [Google Scholar]

- Elgar FJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH, Curtis LJ. Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:441–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis DA, Podolsky CL, Frey M, Naar-King S, Wang B, Moltz K. The role of parental monitoring in adolescent health outcomes: Impact on regimen adherence in youth with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:907–917. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison MM, Katon WJ, Richardson LP. The impact of psychiatric comorbidities on readmissions for diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2150–2154. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, Whitaker RC. A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2002;110:497–504. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MR, Steinberg L. Unpacking authoritative parenting: Reassessing a multidimensional construct. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1999;61:574–587. [Google Scholar]

- Grey M, Whittemore R, Tamborlane W. Depression in type 1 diabetes in children natural history and correlates. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:907–911. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Depression runs in families: The social context of risk and resilience in children of depressed mothers. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington R, Fudge H, Rutter M, Pickles A, Hill J. Adult outcomes of childhood and adolescent depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:465–473. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170065010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood KK. The influence of caregiver depressive symptoms on proxy report of youth depressive symptoms: A test of the depression-distortion hypothesis in pediatric type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:294–303. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Davies M. Adult sequelae of adolescent depressive symptoms. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:255–262. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030073007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane P, Garber J. The relations among depression in fathers, children's psychopathology, and father-child conflict: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Deering CG, Racusin GR. Depressed children and their families. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14:39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Korbel CD, Wiebe DJ, Berg CA, Palmer DL. Gender differences in adherence to type 1 diabetes management across adolescence: The mediating role of depression. Children’s Healthcare. 2007;36:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs Ma, Goldstone D, Obrosky S, Bonar LK. Psychiatric disorders in youth with ISSM: Rates and risk factors. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:36–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRoche C. Children of parents with major affective disorders: A review of the past 5 years. Affective Disorders and Anxiety in the Child and Adolescent. 1989;12:919–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Swales T, Klemp S, Madigan S, Skyler J. Adolescent with diabetes: Gender differences in psychosocial functioning and glycemic control. Children’s Health Care. 1995;24:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard BJ, Jang Y, Savik K, Plumbo PM, Christensen R. Psychosoial factors associated with levels of metabolic control in youth with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2002;17:28–37. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2002.30931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lernmark B, Persson B, Fishert L, Rydelius P. Symptoms of depression are important to psychological adaptation and metabolic control in children with diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine. 1999;16:14–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin AB, Storch EA, Silverstein JH, Baumeister AL, Strawser MS, Geffken GR. Validation of the pediatric inventory for parents in mothers of children with type 1 diabetes: An examination of parenting stress, anxiety, and childhood psychopathology. Families System. 2005;23:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein DN, Gotlib IH. Psychosocial functioning of young adults who have experienced and recovered from major depressive disorder during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:353–363. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss DS, Waller DA, Kennard BD, McIntire D, Capra P, Stephens J. Psychiatric illness and family support in children and adolescents with diabetic ketoacidosis: A controlled study. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:56–544. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199805000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash EJ, Wolfe DA. Abnormal child psychology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Group; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Massengale J. Depression and the adolescent with type 1 diabetes: The covert comorbidity. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2005;26:137–148. doi: 10.1080/01612840590901590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley E, Myers K. Family interactions in mood-disordered youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1992;1:111–127. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Munson JA, Spieker SJ. Paper presented at the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy. Florida: Miami; 1997. The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire: Reliability and validity in a high-risk longitudinal sample. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins LL, Fuemmeler BF, Hoff A, Chaney JM, Van Pelt J, Ewing CA. The relationshop of parental overprotection and perceived child vulnerability to depressive symptomatology in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: The moderating influence of parenting stress. Children’s health Care. 2004;33:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Compas BE. The role of fathers in child and adolescent sychopathology: Make room for daddy. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:387–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racusin GR, Kaslow NJ. Assessment and treatment of childhood depression. In: Keller PA, Heyman SR, editors. Innovations in clinical practice: A source book. Sarasota, FL: USource Press; 2004. pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Ethnocultural differences in prevalence of adolescent depression. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:95–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1024649925737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton JL, Forcier M, Schectman RM. Epidemiology of depressive symptoms in the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:199–205. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sroufe AL. Developmental psychopathology: Concepts and challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:265–296. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KK, Frick PJ, Wootton J. Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard M. Maternal depression, child care and the social work role. British. Journal of Social Work. 1994;24:33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein J, Klingensmith G, Copeland K, Plotnick L, Kaufman F, Laffel L, et al. Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:186–212. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M, Rao U, Emslie GJ, Klein D, White PC. Depressive symptoms predict hospitalization for adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1315–1319. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins TL, Wyatt GE. Child psychosocial adjustment and parenting in families affected by maternal HIV/AIDS. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2008;176:823–838. [Google Scholar]

- Wootton J, Frick PJ, Shelton KK, Silverthorn P. Ineffective parenting and childhood conduct problems: The moderating role of callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:301–308. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.65.2.292.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]