Abstract

Introduction:

We conducted a group-randomized trial to increase smoking cessation and decrease smoking onset and prevalence in 30 colleges and universities in the Pacific Northwest.

Methods:

Random samples of students, oversampling for freshmen, were drawn from the participating colleges; students completed a questionnaire that included seven major areas of tobacco policies and behavior. Following this baseline, the colleges were randomized to intervention or control. Three interventionists developed Campus Advisory Boards in the 15 intervention colleges and facilitated intervention activities. The freshmen cohort was resurveyed 1 and 2 years after the baseline. Two-years postrandomization, new cross-sectional samples were drawn, and students were surveyed.

Results:

At follow-up, we found no significant overall differences between intervention and control schools when examining smoking cessation, prevalence, or onset. There was a significant decrease in prevalence in private independent colleges, a significant increase in cessation among rural schools, and a decrease in smoking onset in urban schools.

Discussion:

Intervention in this college population had mixed results. More work is needed to determine how best to reach this population of smokers.

Introduction

Cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States (Burns, Garfinkel, & Samet, 1997; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004) Despite overall reductions in smoking prevalence in the United States during recent years, the 18- to 29-year age group has the highest prevalence of smoking. Among one of the subgroups of that population, college students (ages 18–24), the prevalence of smoking increased by 28% between 1993 and 1997, from 22.3% in 1993 to 28.5% in 1997 (Wechsler, Rigotti, Gledhill-Hoyt, & Lee, 1998). Recently, smoking prevalence among college students has remained high according to results from the National Institutes of Health survey on drug use, which reported that in 2003, 24.3% of college students had smoked in the past 30 days (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2004). According to the Monitoring the Future Study, rates had fallen to 19.2 in 2006 (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2007).

College is an important period of transition for young adults (Rigotti, Lee, & Wechsler, 2000), and research has demonstrated that 50% of occasional smokers in high school continued to smoke once they reached college, 14.4% converted to daily smoking, and 11.5% of nonsmokers initiated occasional smoking (Wetter et al., 2004). Once smoking is initiated, quitting proves difficult (Patterson, Lerman, Kaufmann, Neuner, & Audrain-McGovern, 2004). Results from one study found that 58.7% of current college smokers attempted to quit at least once (Everett et al., 1999). Although 82.4% of ever-daily smokers also reported attempting to quit, 75.2% were still smokers at the time of interview (Everett et al.). Similarly, a survey of college freshman smokers reported that 63.7% had made at least one unsuccessful quit attempt (Foote et al., 1996).

Although college students have not traditionally been the target of smoking prevention interventions given a lower smoking prevalence compared with their counterparts who do not attend college, the increase in smoking prevalence from 1993 to 1997 within this group has prompted tobacco prevention researchers to focus their efforts toward college students in recent years. Researchers have attempted to identify facilitators of smoking prevention and cessation efforts on college campuses. Cross-sectional results from one national study showed that smoke-free residences were associated with lower smoking prevalence (Wechsler, Lee, & Rigotti, 2001). In contrast, exposure to tobacco promotions on campus, among students who did not already smoke regularly, was associated with initiation or progression of smoking (Rigotti, Moran, & Wechsler, 2005). Compliance with recommended tobacco control policies on public college campuses has traditionally been low (Halperin & Rigotti, 2003) despite research showing student support for such policies among both smokers and nonsmokers (Rigotti, Regan, Moran, & Wechsler, 2003), although notably, no consensus has been reached as to how these policies actually influence smoking initiation, cessation, or prevalence (Borders, Xu, Bacchi, Cohen, & SoRelle-Miner, 2005; Chaloupka & Wechsler, 1997). To date, research is lacking from controlled randomized intervention trials on college campuses to determine what methods or efforts might be effective at preventing smoking onset, facilitating cessation, lowering prevalence, or changing intentions to quit among current smokers.

This study is unique in that 30 four-year colleges and universities in the Pacific Northwest, including public, private independent, and private religious institutions in both rural and urban areas of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, were randomized to receive either a campus-wide tobacco cessation intervention or the usual standard of tobacco cessation efforts. In this paper, we report the main outcomes of the intervention, including its impact on smoking onset, cessation, and changes in smoking prevalence from baseline to follow-up. We hypothesized that a comprehensive intervention would decrease smoking onset, increase cessation rates, and decrease smoking prevalence in intervention campuses compared with control campuses. We posited several additional subhypotheses. Based on the ability to reach students with the limited resources available, we hypothesized that small colleges would show a larger intervention effect than large colleges. Further, we hypothesized that private colleges, as well as religious colleges, would be more likely to respond to the intervention than public colleges. This was stimulated by our observation in previous qualitative work that private and religious colleges often had expressed missions of improving the individual student as a prerequisite for taking steps to make a “difference in the world.” This was also surmised because religious colleges often portrayed the student as a “temple of God” and encouraged that the student’s body be kept pure from addictive substances. Indeed, some of the religious colleges required a vow from students that they would not use alcohol or tobacco (Thompson, Thompson, et al., 2007). Finally, we thought that urban colleges would show a larger intervention effect than rural colleges because urban settings are generally more aware of existing trends; to the extent that smoking cessation and smoking abstinence were becoming more prevalent during the course of the intervention (Johnston et al., 2007), we hypothesized that urban colleges would be more likely to follow that trend than rural colleges. We present the subgroup analyses related to those hypotheses.

Methods

Setting

This study was a group-randomized controlled trial taking place in 30 four-year colleges in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho states. Colleges fell into three categories: public, private independent, and private religious institutions. Schools ranged in size from 500 to 15,000 students. The colleges and universities had a variety of smoking policies, ranging from no policy at all to having restrictive policies on campus.

Baseline survey methods

The overall study design has been described in detail elsewhere (Thompson, Coronado, et al., 2007). Briefly, 30 colleges and universities were recruited by the Spring of 2002. Following recruitment, a qualitative study was conducted to develop the baseline questionnaire (Thompson, Thompson, et al., 2007). A baseline survey was done among students in the participating educational institutions. Sample size varied by the school size; for schools with a large number of students (n = 14), we drew a random sample of all students, oversampling freshmen (n = ∼750), so that we could recruit a cohort to be followed at intervals throughout the study to assess smoking onset during the college years. Of the remaining students, we sampled approximately 200 students per class (i.e., sophomores, juniors, and seniors). For the 16 schools with a smaller number of students (<1,350), we surveyed all students. A total of 30,356 individuals were identified for the baseline survey.

The inclusion criteria for the baseline survey were that students be undergraduate, matriculated, degree-seeking, main campus students. School administrators provided lists of all such students so that we could draw a random sample; random samples of students were drawn from each of the larger institutions, while all students were included from the smaller colleges.

Each identified student received a packet containing a cover letter from the study principal investigator, a cover letter from a school administrator, a scannable questionnaire, a pencil, and a $2.00 bill (U.S.) as an incentive. The cover letter from the principal investigator also included instructions for taking the survey online through our secure web site. The paper and web questionnaires were identical. Two weeks after the initial packet was sent, each student in the sample was sent a reminder postcard asking to return the questionnaire if it had not been done. Two weeks after that, another packet was sent that included a new copy of the questionnaire. This process was repeated two times with mailings to nonrespondents.

Baseline survey content

The student survey focused on seven major areas related to tobacco use: (a) perceptions of tobacco use on campus, (b) perception of smoking policies on campus, (c) perception of activities and events at college that are sponsored by tobacco companies, (d) perception of tobacco prevention or cessation activities on campus, (e) perception of tobacco advertising and promotion on and around campus, (f) tobacco use (current and past), and (g) sociodemographic questions.

Cohort interim survey methods

A total of 6,935 freshmen (42%) responded to the baseline survey; of these, 3,956 freshmen both responded to the baseline survey and provided permission for follow-up contact; these became the freshmen cohort that we followed over time for smoking onset information. Of the cohort, 166 became ineligible for follow-up because they dropped out of school or changed schools. The cohort was followed twice; at 1-year postbaseline, the cohort received a follow-up survey consisting of an abbreviated questionnaire. At the endpoint, 2-year postbaseline, the cohort received the final questionnaire (see below).

The survey distribution method was the same as for the baseline survey, that is, a total of six contacts were made using survey packets and reminder postcards. As an incentive, students received a $5 gift certificate to a campus coffee shop or a nearby off-campus coffee shop if the campus did not have a coffee shop.

Cohort interim survey content

The interim cohort survey consisted of 12 items, including gender, age, and smoking policies at the college; tobacco promotion activities that occurred at the college in the past year; smoking characteristics, such as when the student began smoking, how much the student smoked, and nicotine dependence; other tobacco use; and whether or not the student was enrolled at the same college as in the freshman year.

Final survey methods

A final survey was conducted among members of the freshmen cohort in 2002 and a new cross-sectional random sample of 200 seniors, 200 juniors, 200 sophomores, and 200 freshmen from the 24 schools that had that many students and a census of the 6 smaller schools. After ruling out ineligibles, such as being away (74), withdrawing from school (119), bad addresses (746), and otherwise ineligible (35), this yielded a total of 21,080 students who were eligible to receive the final survey.

The survey was implemented in the same way as the baseline survey, with one exception. Instead of including a $2 bill as an incentive, we included a coupon (worth approximately $3) good for a free coffee drink (e.g., latte, mocha) at a campus coffee stand or a nearby coffee outlet (e.g., Starbucks) if there were no coffee vendors on campus. The same mailing methods were followed so that students received up to six contacts (three survey packets and three postcard reminders).

Final survey content

The final student survey focused on the same seven major areas related to tobacco use as were asked at baseline: (a) perceptions of tobacco use on campus, (b) perception of smoking policies on campus, (c) perception of activities and events at college that are sponsored by tobacco companies, (d) perception of tobacco prevention or cessation activities on campus, (e) perception of tobacco advertising and promotion on and around campus, (f) tobacco use (current and past), and (g) sociodemographic questions. In addition, the final survey included content on awareness of and participation in tobacco control activities over the past 2 years.

All survey materials and procedures were reviewed and approved by Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the individual campus IRB committees.

Intervention

At each of the 15 intervention colleges and universities, we worked with campus contacts to create a Campus Advisory Board (CAB) consisting of faculty, administrators, and students who had an interest in tobacco control. The overall goal of the CABs was to provide information about tobacco control activities that were best suited for that specific college or university. In addition, the CABs assisted in the implementation of the many tobacco control activities that took place on the intervention campuses.

As is common in group-randomized trials, the study was attempting to test a combined intervention that consisted of multiple components (Commit Research Group, 1995a). These intervention activities were summarized in a handbook that was presented to the CABs at the individual colleges. To ensure some commonalty of activities, an intervention manual was created that divided activities into four major categories: (a) increasing the awareness of the dangers of tobacco smoke (Backinger, Fagan, Matthews, & Grana, 2003), (b) increasing campus awareness and enforcement of restrictive tobacco control policies (Ding, 2005), (c) increasing awareness and availability of tobacco cessation resources (Abdullah, Lam, Chan, & Hedley, 2004; Anczak & Nogler, 2003; Mermelstein & Turner, 2006), and (d) increasing awareness of the special strategies employed by the tobacco industry to target special populations, such as minorities and students living in Greek housing (Hammond et al., 2005). As noted above, the intervention activities were selected based on previous studies that had shown effective cessation/prevention activities among adolescents and young adults.

Within each category, there were a number of recommended, suggested, and optional activities (see Table 1). To meet a minimum intervention goal, we asked each intervention college to complete nine recommended activities and any combination of suggested and optional activities during the 2-year intervention period. The recommended intervention activities were designed to be educational and compatible with existing college events, such as Earth Day, World No Tobacco Day, and the Great American Smoke-Out.

Table 1.

Tobacco control activities in the CHAT Study by level of activity

| Activity | Recommended | Suggested | Optional |

| Goal 1: Dangers of tobacco smoke | |||

| Mystery facts campaign | X | ||

| Chalk campaigns | X | ||

| “Tobacco Talk” newspaper columns | X | ||

| Promotional giveaways | X | ||

| World No Tobacco Day | X | ||

| Kick Butts Day | X | ||

| Tobacco death rates for specific colleges | X | ||

| Social norms marketing campaign | X | ||

| Hanging “Pats” with ETS messages | X | ||

| Tobacco Jeopardy game | X | ||

| Tobacco “tombstone” display | X | ||

| Cigarettes in a jar contest | X | ||

| Campus clean up | X | ||

| Tobacco counteradvertising contest | X | ||

| Antitobacco advocates | X | ||

| Ciggy buttz costume | X | ||

| In memory display | X | ||

| Goal 2: Tobacco control policies | |||

| Chalk box at nonsmoking areas | X | ||

| Forums about smoking policies | X | ||

| Strategic reduction of ashtrays | X | ||

| Observational study of policies and practices | X | ||

| Stricter tobacco policies | X | ||

| Enforcement plans for existing policies | X | ||

| Audit of campus no smoking signs | X | ||

| Mark magazines with tobacco ads | X | ||

| Writing grant proposals | X | ||

| Goal 3: Cessation resources | |||

| Promote tobacco quitline | X | ||

| Promote the CHAT TO QUIT web site | X | ||

| In-service program for campus health staff | X | ||

| Charting tobacco as a vital sign | X | ||

| Great American Smoke-Out | X | ||

| Promote cessation activities at health center | X | ||

| Motivational E-mails to students | X | ||

| Develop support program for quitters | X | ||

| Train student leaders to provide cessation | X | ||

| Prepare and distribute quit kits | X | ||

| Provide cessation info at campus events | X | ||

| Organize a quit for a day event | X | ||

| Organize quit and win contest | X | ||

| Conduct campus challenge program | X | ||

| Follow-up students who request assistance | X | ||

| Place information kiosks on campus | X | ||

| Develop cessation course | X | ||

| Cover NRT through campus health plan | X | ||

| Goal 4: Special population groups | |||

| Tobacco industry teasers | X | ||

| Show “The Insider” or other relevant videos | X | ||

| Display tobacco industry holdings | X | ||

| Contact national Greek chapters | X | ||

| Construct truth in tobacco ads display | X | ||

Note. CHAT = Campus Health Action on Tobacco; ETS = Environmental Tobacco Smoke; NRT = nicotine replacement therapy.

As examples, one popular activity was a “tombstone display” where cardboard “tombstones” were placed in a grassy area on the college campuses. This ersatz cemetery contained the names of fictional people who had died from a tobacco-related disease. The activity created much conversation on campus. Another example was a “Jeopardy” game where answers were placed on a board and students had to guess the question. In policy activities, students drew chalk boxes around entrances to buildings to show where smoke-free areas existed or should exist. In the cessation resources activities, a project sponsored web site offered a quit program; similarly, a telephone service provided quit information and assistance. In the special populations groups activities, “truth in tobacco advertising” displays were made and positioned on campuses. The full list of activities is given in Table 1.

Three interventionists worked with the 15 intervention colleges and universities. They regarded their role primarily as being facilitators of the CAB. The CABs made decisions about the types of activities to be done and who should do them. The interventionists were usually on hand at major events, but a number of events were implemented by CAB members and other volunteers.

Outcome variables

This paper focuses on three outcome variables: smoking cessation rates, prevalence of smoking, and onset of smoking. Smoking cessation rates were calculated as long-term cessation, that is, as having been an ever-smoker and having quit for 6 months or more at the time of the last survey or being a short-term quitter, that is, having quit for 31 days to 6 months at the time of the last survey. Prevalence was assessed as having smoked at all, even a puff, in the last 30 days. Onset of smoking was assessed by a negative smoking status at baseline followed by a positive smoking status (i.e., smoked in the past 30 days) at the final follow-up survey in the freshmen cohort.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed accounting for differential sampling rates both across classes within institutions as well as across institutions. Sampling rates were determined as the number of returned surveys from each class divided by the class count. Of note, the fall class lists used to determine who should receive the baseline survey overestimated the number of students enrolled for each class. In particular, the freshman class lists for each year included many students who have been accepted but never actually appear on campus, perhaps because they had been accepted at multiple colleges. In order to obtain more accurate class counts reflecting who was enrolled for the fall term, institutional fall class lists were compared with spring class lists. Only students appearing on the spring class list were assumed actually enrolled for the fall term. This may include some students who dropped out after fall semester; however, informants at the colleges believed that this was a lesser problem than the fall overenrollment.

Statistical analyses were carried out using SUDAAN 7.5 (Shah, Barnwell, & Bieler, 1997) and SAS v. 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, 2004a). Statistical analyses were performed accounting for sampling design issues (students nested within class within school) and corresponding differential sampling rates across classes within institutions as well as across institutions. Sampling weights were constructed to reflect unequal probabilities of selection arising from the sample design and survey nonresponse. Intervention effects were examined for binary response variables (smoking prevalence, short- and long-term smoking cessation, and smoking onset) using the SUDAAN logistic procedure to account for sample design and sampling weights.

Logistic regression also was employed to examine secondary hypotheses about intervention dose effects where dose was measured by the total number of intervention activities and participation by the percent college students participating in project events.

Prevalence and cessation variables were obtained from baseline and follow-up surveys. For these response variables, the intervention effect was obtained as the treatment arm by time interaction in a model that included arm and time main effects. School size (small, medium, and large), affiliation (public, religious, and independent), and rural/urban status were employed as adjustment covariates. Smoking onset was obtained from the follow-up survey for students who indicated that they were nonsmokers at baseline. For smoking onset, only the intervention arm and adjustment covariates were included in the prediction model.

Specific effects such as within treatment differences between baseline and follow-up log odds (for the three response variables that were measured at baseline and follow-up) were obtained by exporting the parameter estimates and associated covariance matrix generated by SUDAAN’s logistic procedure to SAS. The SAS/interactive matrix language procedure was used to compute and for L representing the contrast of interest. Also computed in SAS are estimates of prevalence and smoking cessation and onset rates computed as where the coefficients of L are determined employing the same rules as used to compute least squares mean estimates in the SAS GLM procedure (see SAS/STAT documentation, “the GLM procedure,” and subsection “details/comparing groups/construction of least squares means” (SAS Institute, 2004b).

Descriptive statistics regarding demographic characteristics of survey respondents were computed under simple random sample assumptions (i.e., without regard to the sample design and sampling weights). In contrast, descriptive statistics related to study outcomes (e.g., proportion of students who smoked at baseline) were computed employing design considerations using the SUDAAN CROSSTAB procedure.

Results

Response rates

At baseline, a total of 14,237 students responded for an overall response rate of 46.9%, which ranged from 29% to 58% depending on school. Freshmen respondents comprised 6,935 (48.7%) of the total respondents. Responses to the web site consisted of 21.6% of those. A comparison of web site and scannable forms indicated no difference in sociodemographics (age, gender, class in school, type of school attended, and grade point average) by type of questionnaire completed.

At the final survey, a total of 9,627 students (45.7%) responded to the final cross-sectional survey. Response rates varied from 20.1% to 51.1% depending on school. Web respondents comprised 16.1% of the sample, and there were no sociodemographic differences between respondents by type of survey completed.

At 1-year postbaseline, 64.1% of cohort members responded to the survey; at 2 years, 75.8% of those respondents answered the final survey, for an overall response rate of 48.6%.

Student demographics

The characteristics of the students in intervention and control schools are shown in Table 2. Nearly two third of respondents were women. Freshmen represented slightly less than one half of the total number of students at baseline and only 20% at follow-up. This difference is due to the cohort of first-year students enrolled in the study at baseline and reinterviewed at follow-up. Nearly all students were enrolled full time. About 85% of students were Caucasian/White, and this percentage was constant across survey timepoints. At both baseline and follow-up timepoints, about 5% of students were of Hispanic ethnicity. Age distribution differed by survey timepoint, with about one half of students at baseline being ages 15–19 and one third of students at follow-up surveying matching this category. This difference is likely due to the cohort of first-year students enrolled in the study. Grade point average was similar across survey timepoints, with the majority of students reporting a grade point average ranging from 3.0 to 4.0.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of study sample at baseline and follow-up timepoints

| Baseline |

Follow-up |

|||

| Control |

Intervention |

Control |

Intervention |

|

| Characteristic | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 5,063 (66.0) | 4,310 (66.7) | 3,395 (69.5) | 3,238 (69.8) |

| Male | 2,603 (34.0) | 2,150 (33.3) | 1,493 (30.5) | 1,402 (30.2) |

| Class standing | ||||

| Freshmen | 3,560 (46.3) | 2,863 (44.2) | 1,073 (21.9) | 940 (20.2) |

| Sophomore | 1,329 (17.3) | 1,254 (19.4) | 1,141 (23.2) | 1,055 (22.6) |

| Junior | 1,416 (18.4) | 1,215 (18.8) | 1,520 (31.0) | 1,538 (33.0) |

| Senior | 1,388 (18.0) | 1,142 (17.6) | 1,174 (23.9) | 1,131 (24.2) |

| Full time/part-time | ||||

| Full time | 7,227 (94.2) | 6,262 (96.9) | 4,703 (96.8) | 4,492 (97.4) |

| Part-time | 394 (5.1) | 178 (2.7) | 123 (2.5) | 73 (1.6) |

| Other | 47 (0.6) | 25 (0.4) | 34 (0.7) | 48 (1.0) |

| Race | ||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 438 (5.8) | 507 (7.9) | 282 (5.9) | 305 (6.7) |

| African American/Black | 98 (1.3) | 71 (1.1) | 43 (0.9) | 34 (0.7) |

| Native American/American Indian | 89 (1.2) | 76 (1.2) | 57 (1.2) | 63 (1.4) |

| Caucasian/White | 6,491 (85.9) | 5,419 (84.6) | 4,084 (85.6) | 3,904 (85.1) |

| Other | 257 (3.4) | 150 (2.3) | 21 (0.4) | 19 (0.4) |

| More than one race | 67 (0.9) | 70 (1.1) | 125 (2.6) | 133 (2.9) |

| Unknown/not reported | 115 (1.5) | 109 (1.7) | 157 (3.3) | 128 (2.8) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||||

| Yes | 472 (6.2) | 278 (4.3) | 315 (6.5) | 217 (4.7) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 15–19 | 3,636 (48.3) | 3,209 (50.7) | 1,587 (33.7) | 1,525 (34.0) |

| 19 | 1,058 (14.1) | 943 (14.9) | 1,058 (22.5) | 1,019 (22.7) |

| 20 | 1,003 (13.3) | 753 (11.9) | 830 (17.6) | 779 (17.4) |

| 21 | 435 (5.8) | 344 (5.4) | 327 (6.9) | 280 (6.2) |

| 22 or older | 1,397 (18.6) | 1,084 (17.1) | 904 (19.2) | 885 (19.7) |

| Grade point average | ||||

| Less than 2.0 | 37 (0.7) | 31 (0.7) | 11 (0.3) | 26 (0.6) |

| 2.0–2.99 | 982 (18.7) | 691 (16.0) | 652 (16.0) | 624 (14.8) |

| 3.0–3.49 | 1,994 (38.0) | 1,611 (37.2) | 1,481 (36.3) | 1,478 (35.0) |

| 3.5–3.99 | 2,038 (38.8) | 1,811 (41.8) | 1,817 (44.6) | 1,921 (45.5) |

| 4.0 or greater | 198 (3.8) | 185 (4.3) | 115 (2.8) | 176 (4.2) |

Notes. *Percentages based on non-missing values.

**5,862 students did not report grade point average (4,589 at baseline and 1,273 at follow-up).

When we examined statistical difference in baseline characteristics by intervention or control status, we found several significant differences (see Table 2). Gender distribution was similar across intervention and control sites; however, significant differences by intervention arm were observed in the distribution of full time/part-time status, race, Hispanic ethnicity, and grade point average (see Table 2). Despite statistically significant differences in these factors, none were considered meaningfully different (see Table 2) and would not likely introduce bias in our findings. We did not test for differences between intervention and control sites in class standing or in age since an oversampling of first-year students was part of the study design.

Intervention activities

Table 3 summarizes the number of activities conducted at each school. The numbers ranged from 6 to 113, with a mean of 42 activities. Table 3 also shows the number of participants in the activities by school, measured by attendance at events, and the percent participation of the total student body. This latter is somewhat misleading in that a single student may have participated in more than one activity; nevertheless, it gives a rough approximation of student body involvement.

Table 3.

Summary of intervention activities by school

| School | Total activities | Total participants | Percent participation of all students at the school |

| A | 21 | 688 | 100 |

| B | 54 | 3,702 | 49 |

| C | 52 | 2,295 | 77 |

| D | 6 | 310 | 28 |

| E | 38 | 1,562 | 69 |

| F | 55 | 1,317 | 9 |

| G | 23 | 2,274 | 78 |

| H | 40 | 745 | 66 |

| I | 59 | 1,246 | 11 |

| J | 43 | 3,643 | 100 |

| K | 40 | 440 | 14 |

| L | 36 | 3,841 | 45 |

| M | 113 | 7,674 | 53 |

| N | 21 | 633 | 100 |

| O | 34 | 1,068 | 64 |

| Total | 635 | 31,438 | 42 |

School characteristics

Schools were matched on school affiliation and size and randomized to either the intervention or the control condition. Two third of control schools and 40% of intervention schools were rural (Table 4).

Table 4.

Differences in smoking prevalence in control and intervention schools by school characteristic

| Control |

Intervention |

Control |

Intervention |

|

| School type | n (%) | n (%) | % Prevalence | % Prevalence |

| School affiliation | ||||

| Public | 6 (40.0) | 7 (46.7) | 30 | 32.2 |

| Religious | 5 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | 24.8 | 15.7 |

| Independent | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20.0) | 25.5 | 29.9*** |

| Rural/urban status | ||||

| Rural | 10 (66.7) | 6 (40.0) | 24.5 | 25.7 |

| Urban | 5 (33.3) | 9 (60.0) | 25.5 | 27.2 |

| School size | ||||

| Small | 7 (46.7) | 6 (40.0) | 25.5 | 22.2 |

| Medium | 4 (26.7) | 4 (26.7) | 29.2 | 26.3 |

| Large | 4 (26.7) | 5 (33.3) | 23.7 | 26.1** |

Note. **Significant at p < .01

***Significant at p < .01.

Overall, 28.3% of students at baseline reported being current smokers. As shown in Table 4, slightly less than one third (29.4%) of students in public school reported being a current smoker, and this proportion was higher than that reported for religious (20.9%) and independent schools (28.7%). Nearly equal proportions of students in rural (28.6%) and urban (27.2%) schools were current smokers. Nearly one quarter of students in small and large schools reported being a current smoker, and this proportion was slightly higher in medium-sized schools (small: 23.5%, medium: 26.8%, and large: 29.3%). When we examined baseline prevalence of smoking in our intervention and control schools, we found significant difference by school affiliation and size. There were no statistical differences in smoking prevalence by urban/rural designation.

Main outcome findings

As shown in Table 5, among students attending intervention schools, nearly one quarter of students reported being current smokers at baseline, and this proportion did not change at final data collection in intervention schools (26.1%). Similarly, there was no change in smoking prevalence from baseline to follow-up among students in the control schools. When we examined the long-term quit rate, we found that at baseline, 23.4% of students in control sites and 26.9% of students in intervention sites reported long-term cessation (6 months or more). These proportions dropped slightly in both control and intervention schools, but the differences were not significant. Approximately half of students in both control and intervention schools reported having quit for up to 30 days but less than 6 months (short-term cessation) at baseline, and this percentage did not change significantly in follow-up data for either group. Smoking onset was not significantly different by intervention or control group status. We observed no significant difference between the intervention and control schools overall in any of our smoking variables.

Table 5.

Log odds ratios for prevalence, quit rate (long and short term), and smoking onset probabilities in intervention and control arms at baseline and follow-up, adjusted for college characteristics (size, affiliation, and rural/urban environment)

| Control |

Intervention |

||||||

| Response | Baseline | Follow-up | Difference | Baseline | Follow-up | Difference | Effect |

| Prevalence | |||||||

| Log odds | 0 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| CI | — | (−0.17 to 0.05) | (−0.17 to 0.05) | (−0.06 to 0.17) | (−0.06 to 0.18) | (−0.12 to 0.13) | (−0.10 to 0.23) |

| Estimated probability | 24.8 | 23.8 | −1.1 | 25.9 | 26.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Quit rate (long term) | |||||||

| Log odds | 0 | −0.11 | −0.11 | 0.18 | −0.19 | −0.38 | −0.27 |

| CI | — | (−0.32 to 0.10) | (−0.32 to 0.10) | (−0.02 to 0.39) | (−0.41 to 0.03) | (−0.59 to −0.16) | (−0.57 to 0.03) |

| Estimated probability | 23.4 | 21.5 | −1.9 | 26.9 | 20.2 | −6.8 | −4.8 |

| Quit rate (short term) | |||||||

| Log odds | 0 | −0.11 | −0.11 | 0.13 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.03 |

| CI | — | (−0.28 to 0.06) | (−0.28 to 0.06) | (−0.04 to 0.29) | (−0.13 to 0.22) | (−0.26 to 0.10) | (−0.22 to 0.28) |

| Estimated probability | 48.3 | 45.5 | −2.8 | 51.4 | 49.4 | −2.0 | 0.7 |

| Smoking onset | |||||||

| Log odds | 0 | 0.16 | 0.16 | ||||

| CI | — | (−0.36 to 0.68) | (−0.36 to 0.68) | ||||

| Estimated probability | 16.8 | 19.1 | 2.4 | ||||

Note. CIs for the log odds ratios are shown in parentheses. In addition, estimated probabilities for each response are shown.

Effect modification

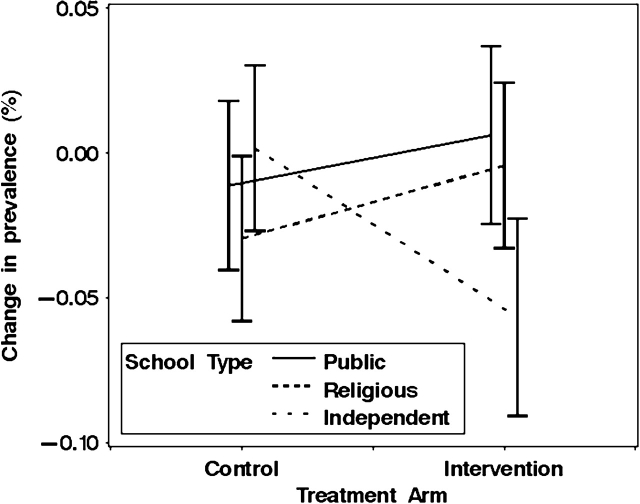

When we examined changes in smoking prevalence at baseline and final survey timepoints in our intervention and control communities, we found notable differences by school type (Figure 1). Smoking prevalence was nearly unchanged in public and religious schools across survey timepoints. In contrast, among independent schools, changes in smoking prevalence differed by intervention status, with those in the intervention arm having a reduction in prevalence, whereas those in the control arm having prevalence that remained unchanged (χ2 = 7.72, df = 2, p < .05). These findings suggest that the intervention successfully reduced smoking among students attending independent schools.

Figure 1.

Prevalence changes by college type and treatment arm.

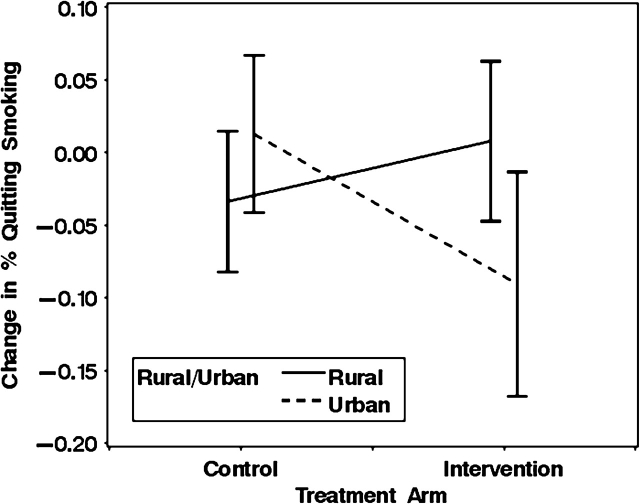

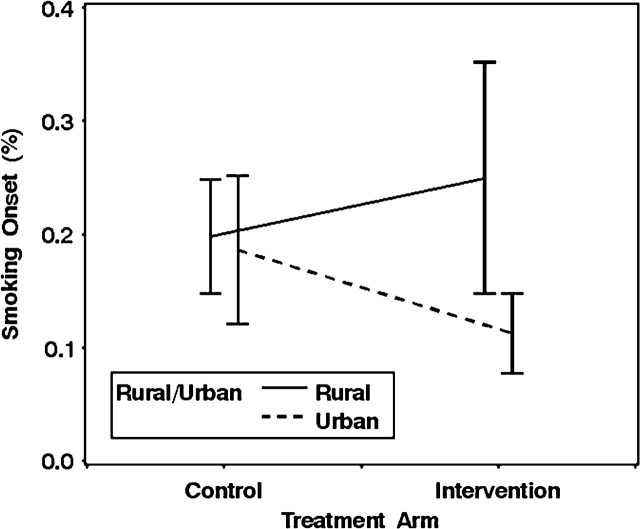

Although no meaningful differences were observed in changes in smoking prevalence among schools defined by size or urban/rural designation, significant differences were observed in the proportion of students who quit smoking for at least 6 months during the intervention when the data were stratified by urban/rural designation (χ2 = 5.65, df = 1, p < .05) (Figure 2). Among rural schools, changes between baseline and final data collection in the proportion of students who had quit smoking were higher in intervention schools than in controls, and the reverse was true for urban schools. In contrast, among rural schools, the relative proportion of students who started smoking was higher in intervention compared with control schools (Figure 3). A reverse trend was noted in relative proportions of smoking onset among students in urban schools (χ2 = 4.99, df = 1, p < .01). These data suggest that in rural schools, the intervention may have been more effective in motivating students to quit smoking, and in urban schools, the intervention was more effective at motivating students not to start.

Figure 2.

Quit rates by setting and treatment arm.

Figure 3.

Onset by setting and treatment arm.

Dose–response

We assumed that the large variability between colleges in terms of implementing the intervention might be associated with the trial outcomes. We ran regressions looking at dose in terms of the number of activities conducted and in terms of percentage of participation. We ran each dose variable (activities and participation) separately, then together, and repeated that while adjusting for school affiliation, size, and rural/urban classification for each of the three outcomes, prevalence, smoking cessation, and onset. For prevalence, there was a positive relationship between activities and prevalence (p < .001), but there was no association for participation and prevalence. When the two variables were entered together, activity and prevalence again had a positive association (p < .001), but participation was inversely associated with prevalence (p < .001). These associations held when adjusting for school type, size, and rural/urban classification.

Neither total activity nor percent participation had any significant effect on smoking cessation. For smoking onset, the trends followed those of prevalence in that activity was positively associated with onset (p < .05), and participation was inversely associated with onset (p < .05) when the two variables were entered together. This held when adjusting for school type, size, and rural/urban classification.

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial of 30 colleges and universities in the Pacific Northwest, we found no significant overall differences between intervention and control schools when examining smoking cessation, smoking prevalence, or smoking onset. The overall results were somewhat disappointing but not unusual given findings from other group-randomized trials, which tend to demonstrate small, if any, effects (Commit Research Group, 1995aM, 1995b; Peterson, Kealey, Mann, Marek, & Sarason, 2000; Thompson, Coronado, Chen, & Islas, 2006).

There are a number of potential reasons to explain the overall nonsignificant effects. The intervention intensity was relatively low compared with the number of students we were attempting to reach. The project had only three interventionists “on the ground,” and each interventionist had to cover five schools. The distance of some of the schools from the research center in Seattle presented additional challenges in that interventionists had to travel long distances to facilitate college events and activities. Practically, this meant that the interventionists had limited time at each college.

It was thought that organizing a CAB at each college would help in intervention implementation, but CAB composition and size varied considerably by college. Total CAB members over the life of the project varied from 5 members to more than 1,000 members depending on college. Further, some CABs were very active while others relied heavily on the interventionist to plan and implement activities. The number of activities done by colleges also varied (see Table 1), suggesting that intervention intensity was uneven among the different colleges.

Additionally, the length of the intervention was only 2 years. Given the size of many of the campuses, this was a short time to reach out to smokers or would-be smokers. In addition to the problem of spreading the message throughout large colleges, it is well known that smokers often deliberate for some time before quitting for good (Jaroni, Wright, Lerman, & Epstein, 2004; Pisinger, Vestbo, Borch-Johnsen, & Jorgensen, 2005). Furthermore, it may be that a change at an organizational or community level requires a longer period of time. In the Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation (COMMIT), it was only after 2 years into the trial when there appeared to be a difference between intervention and control communities (Thompson, Lynn, & Shopland, 1995). Similarly, the North Karelia study did not see a difference in smoking status until 10-year postintervention (Puska & Koskela, 1983) For the present study, it is possible that a longer intervention could have shown an effect.

A common problem with community-type projects is that the intervention is spread across a wide population base, which makes it difficult to detect small changes. Individuals randomized to intervention in individual randomized trials often show a smoking cessation effect, but they are rare in community trials (Bauman, Suchindran, & Murray, 1999; Terrin, 1997; Thompson, Coronado, Snipes, & Puschel, 2003). Group-randomized trials may minimize the dose of intervention because of resource issues. This in combination with accelerating secular trends may make it difficult to assess an effect (Bauman et al.). As previously mentioned, smoking among college students is decreasing nationally, and it is possible that the national trend obscured any effect this study may have had.

We are encouraged in that we did find differences in prevalence when examining the intervention effect according to school type. Among public schools and religious schools, there was no decrease in prevalence; however, there was a significant decrease in prevalence when examining private independent colleges. There are a number of potential reasons that this may have occurred. For religious schools, there was a lower prevalence at baseline relative to the public and private independent schools. This may be because religious schools have a philosophy of keeping the body clean as it represents the “temple of God.” Indeed, in at least three of the private religious colleges, smoking was not allowed on campus and in at least two, students had to sign pledges not to smoke while at college. These kinds of activities may have prevented prevalence from decreasing much more in the private religious schools.

Furthermore, private independent schools have a reputation for being concerned with the earth and environment, and it may be that more students in private independent schools became interested in contributing to the project. Similarly, the geographic limitation of the campuses in private independent colleges may have resulted in more students being influenced by activities, such as the artificial tombstones set up to commemorate the ills of smoking.

The difference in smoking cessation between urban and rural schools is somewhat puzzling. Smokers in rural schools were more likely to achieve cessation than those in urban schools. It is possible that students in urban schools have a variety of activities to occupy their time, and thus, they are less likely to pay attention to smoking cessation messages. Students in rural schools, on the other hand, may have been more aware of the intervention and may have attempted cessation as a result. The web site and telephone support available to all students in the intervention schools may have been more palatable to rural students than urban students. Further analyses are examining this hypothesis.

On the other hand, among the cohort of freshmen, students in rural schools were more likely to start smoking while those in urban schools were less likely to start smoking over the course of the trial. Nationally, there has been a trend for college students to reduce smoking onset (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & JE, 2007); it may be that students in urban settings are likely to be influenced by this trend earlier than those in rural settings. Thus, students in rural schools who began smoking during college may serve as the “low-hanging fruit” in terms of the intervention effect. From analysis of smoking onset at the interim and final measures, it also is clear that smoking onset is extremely unstable (data not shown), with much variation among students in smoking status at different timepoints, and it is possible that the trend we identified could be reversed in a subsequent survey.

Finally, the large variability among colleges in terms of implementing the intervention might be associated with the trial outcomes. As noted in the results, we ran regressions looking at dose in terms of number of activities conducted and in terms of percentage of participation. The relationship between number of activities and prevalence is counterintuitive; however, it may be that those schools with higher prevalence were more aware of the problem they faced regarding smoking, and thus, they may have conducted more activities. Certainly, this is true for schools E, I, and M where activities were well beyond expectations. The finding that participation in project activities was significantly associated with lower prevalence substantiates a positive dose/response association. That there was no association between activities and participation and smoking cessation is similar to our overall findings that smoking cessation did not occur as a result of the intervention. This held regardless of dose and is somewhat discouraging in that smoking cessation was a main outcome. On the other hand, smoking onset was related to both activities and participation, lending credence to the idea that schools with high smoking prevalence may have been aware of the problem smoking presented for the school and thus engaged in more activities. Participation in such situations was associated with lower onset, suggesting that dose may have made a difference in smoking onset.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The response rate from students was low given the effort that went into obtaining responses. Others have experienced response rates that are somewhat higher. Rigotti et al. (2005) received response rates of 70% (1993), 60% (1997), 60% (1999), and 52% in 2001 in The Harvard College Alcohol Study. In addition, they eliminated schools with very low response rates. The National College Health Risk Behavior Survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control in 1995 yielded a 65% response rate; however, phone calls were made to nonresponding students. Comparisons of web-based and mailed surveys yielded results of 58.3% and 62%, respectively (Pealer, Weiler, Pigg, Miller, & Dorman, 2001). In another study, an E-mail survey to college students had a response rate of 56.1% (DeBernardo et al., 1999). Our response rates fall under those; however, as The Harvard College Alcohol Study suggests, there is some indication that student response to surveys of this kind is degrading over time (Brummett et al., 2002).

One potential limitation that might be attributed to the low response rates is that bias in survey participation may have resulted; thus, responders may primarily have been those who participated in activities. We examined, however, the response rates to the cohort and found their response rates to the endpoint survey higher (75.8% at 2-year follow-up) than the cross-sectional sample, giving us some confidence that participation in intervention activities was not a major factor in the results.

Nevertheless, it is clear that our response rates to the cross-sectional survey were low. This has implications for the representativeness of the data. Others have noted that smokers are less likely to respond to surveys about smoking (Biener, Aseltine, Cohen, & Anderka, 1998; Biener, Garrett, Gilpin, Roman, & Currivan, 2004; Wechsler et al., 1998). It may be that this is the case here. The smoking prevalence rates reported here, for example, are somewhat lower than those reported in other college smoking studies (Curtin, Presser, & Singer, 2000; Freier, Bell, & Ellickson, 1991; Steeh, Kirgis, Cannon, & DeWitt, 2001). Biener et al. (2004) investigated whether there was associated bias in smoking prevalence as a result of lower response rates. In an examination of Massachusetts and California tobacco surveys compared with estimates from the Current Population Survey Tobacco Use Supplement, they found no evidence that declining response rates to tobacco surveys resulted in less accurate estimates of smoking behavior. However, they did not focus on college student smoking; thus, these results should be interpreted cautiously.

Some of our responses were not as clear as we would have liked. As an example, we asked smokers if they considered themselves a “regular smoker,” leaving it up to the respondent to define for himself/herself what “regular” was (Harris, Schwartz, & Thompson, 2008). Nevertheless, we desired to keep our survey simple and short; thus, in addition to using standard items, we included items that were considered “intuitively” understandable.

The results reported here are from 4-year colleges. It is thought that smoking rates are higher among 2-year college students (Brummett et al., 2002), and indeed, smoking rates overall in the 18- to 24-year-old group are now the highest in the country (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004). We were unable to survey other segments of the 18- to 24-year-old population; thus, our results apply only to 4-year college undergraduates. Similarly, they can be generalized only to colleges in the Northwest. Smoking rates in the Northwest are generally lower than some other parts of the United States, which also may account for the lower smoking rates than those reported by other college studies.

Conclusion

This group-randomized trial of smoking cessation, smoking prevalence, and smoking onset among college students in 30 Northwest colleges and universities had nonsignificant overall outcomes, suggesting that the college-wide interventions employed here were ineffective in reducing prevalence and smoking onset and increasing cessation overall. An examination of subgroups, however, indicated an effect in reducing the smoking prevalence among private independent schools compared with public and private religious schools. Similarly, there was increased cessation in rural compared with urban schools. Urban colleges, however, had lower smoking onset than rural colleges. The smoking rate among college students is decreasing over time, and interventions may be more difficult as the remaining college smokers are those who are most entrenched in the habit.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant (No. CA93967) from the Tobacco Control Branch of the National Cancer Institute through their State and Community Intervention for Tobacco Control Initiative.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We thank the state health departments of Oregon and Washington for assisting in this endeavor. We are also grateful to the 30 colleges and universities participating in this project.

References

- Abdullah ASM, Lam TH, Chan SSC, Hedley AJ. Which smokers use the smoking cessation quitline in Hong Kong, and how effective is the quitline? British Medical Journal. 2004;13:415–421. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anczak JD, Nogler RA. Tobacco cessation in primary care: Maximizing intervention strategies. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2003;1:201–216. doi: 10.3121/cmr.1.3.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backinger CL, Fagan P, Matthews E, Grana R. Adolescent and young adult tobacco prevention and cessation: Current status and future directions. British Medical Journal. 2003;12:iv46–iv53. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_4.iv46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Suchindran CM, Murray DM. The paucity of effects in community trials: Is secular trend the culprit? Preventive Medicine. 1999;28:426–429. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Aseltine RH, Jr., Cohen B, Anderka M. Reactions of adult and teenaged smokers to the Massachusetts tobacco tax. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1389–1391. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Garrett CA, Gilpin EA, Roman AM, Currivan DB. Consequences of declining survey response rates for smoking prevalence estimates. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:254–257. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders TF, Xu KT, Bacchi D, Cohen L, SoRelle-Miner D. College campus smoking policies and programs and students’ smoking behaviors. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Mark DC, Williams RB, Siegler IC, Clapp-Channing N, et al. Predictors of smoking cessation in patients with a diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation. 2002;22:143–147. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns D, Garfinkel L, Samet JM. Changes in cigarette-related disease risks and their implication for prevention and control. 1997. (NIH Publication No. 97–1213) (Monograph No. 8). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults–United States, 2002. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53:427–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka FJ, Wechsler H. Price, tobacco control policies and smoking among young adults. Journal of Health Economics. 1997;16:359–373. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(96)00530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commit Research Group. Community intervention trial for smoking cessation (COMMIT): I. Cohort results from a four-year community intervention. [Clinical trial randomized controlled trial] American Journal of Public Health. 1995a;85:183–192. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commit Research Group. Community intervention trial for smoking cessation (COMMIT): II. Changes in adult cigarette smoking prevalence. [Clinical trial randomized controlled trial] American Journal of Public Health. 1995b;85:193–200. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.2.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. The effects of response rate changes on the index of consumer sentiment. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2000;64:413–428. doi: 10.1086/318638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBernardo RL, Aldinger CE, Dawood OR, Hanson RE, Lee SJ, Rinaldi SR. An E-mail assessment of undergraduates’ attitudes toward smoking. Journal of American College Health. 1999;48:61–66. doi: 10.1080/07448489909595675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding A. Curbing adolescent smoking: A review of the effectiveness of various policies. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2005;78:37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett SA, Husten CG, Kann L, Warren CW, Sharp D, Crossett L. Smoking initiation and smoking patterns among US college students. Journal of American College Health. 1999;48:55–60. doi: 10.1080/07448489909595674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote JA, Harris RB, Gilles ME, Ahner H, Roice D, Becksted T, et al. Physician advice and tobacco use: A survey of 1st-year college students. Journal of American College Health. 1996;45:129–132. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1996.9936872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freier MC, Bell RM, Ellickson PL. Do teens tell the truth? The validity of self-reported tobacco use by adolescents. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin AC, Rigotti NA. US public universities’ compliance with recommended tobacco-control policies. Journal of American College Health. 2003;51:181–188. doi: 10.1080/07448480309596349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D, Tremblay I, Chaiton M, Lessard E, Callard C Tobacco on Campus Workgroup. Tobacco on campus: Industry marketing and tobacco control policy among post-secondary institutions in Canada. Tobacco Control. 2005;14:136–140. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JB, Schwartz SM, Thompson B. Characteristics associated with self-identification as a regular smoker and desire to quit among college students who smoke cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:69–76. doi: 10.1080/14622200701704202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaroni JL, Wright SM, Lerman C, Epstein LH. Relationship between education and delay discounting in smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1171–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L, O’Malley P, Bachman J, Schulenberg J. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975-2003; Volume II: college students and adults ages 19–45. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2004. (NIH Publication No. 04-5508) [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L, O’Malley P, Bachman J, Schulenberg J. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2006 (Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–45) Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein R, Turner L. Web-based support as an adjunct to group-based smoking cessation for adolescents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:69–76. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson F, Lerman C, Kaufmann VG, Neuner GA, Audrain-McGovern J. Cigarette smoking practices among American college students: Review and future directions. Journal of American College Health. 2004;52:203–210. doi: 10.3200/JACH.52.5.203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pealer LN, Weiler RM, Pigg RM, Jr., Miller D, Dorman SM. The feasibility of a web-based surveillance system to collect health risk behavior data from college students. [Clinical trial randomized controlled trial validation studies] Health Education & Behavior. 2001;28:547–559. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AV, Jr., Kealey KA, Mann SL, Marek PM, Sarason IG. Hutchinson smoking prevention project: Long-term randomized trial in school-based tobacco use prevention–results on smoking. [Clinical trial randomized controlled trial] Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:1979–1991. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.24.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisinger C, Vestbo J, Borch-Johnsen K, Jorgensen T. It is possible to help smokers in early motivational stages to quit. The Inter99 study. [Clinical trial randomized controlled trial] Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puska P, Koskela K. Community-based strategies to fight smoking. Experiences from the North Karelia project in Finland. New York State Journal of Medicine. 1983;83:1335–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti NA, Moran S, Wechsler H. US college students’ exposure to tobacco promotions: Prevalence and association with tobacco use. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:138–144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti NA, Regan S, Moran S, Wechsler H. Students’ opinion of tobacco control policies recommended for US colleges: A national survey. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:251–256. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.3.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti NA, Lee JE, Wechsler H. US college students’ use of tobacco products: Results of a national survey. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:699–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. SAS 9.1.3 help and documentation. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2004a. 2000–2004. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. SAS support. 2004b. Retrieved 18 January 2007, from http://support.sas.com/onlinedoc/913/getDoc/en/statug.hlp/glm_sect39.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Shah B, Barnwell B, Bieler G Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN user’s manual, release 7.5. Research Triangle Park, NC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Steeh C, Kirgis N, Cannon B, DeWitt J. Are they really as bad as they seem? Nonresponse rates at the end of the twentieth century. Journal of Official Statistics. 2001;17:227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Terrin ML. Individual subject random assignment is the preferred means of evaluating behavioral lifestyle modification. [Review] Controlled Clinical Trials. 1997;18:500–505. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00021-4. discussion, 514–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B, Coronado G, Chen L, Islas I. Celebremos La Salud! A community randomized trial of cancer prevention (United States). [randomized controlled trial] Cancer Causes and Control. 2006;17:733–746. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B, Coronado G, Chen L, Thompson LA, Halperin A, Jaffe R, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of smokers at 30 Pacific Northwest colleges and universities. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:429–438. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B, Coronado G, Snipes S, Puschel K. Methodologic advances and ongoing challenges in designing community-based health promotion programs. [Review] Annual Review of Public Health. 2003;24:315–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B, Lynn W, Shopland D. What have we learned and where do we go from here? Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, NIH, NCI; 1995. (Vol. Monograph 6) [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B, Thompson LA, Hymer J, Zbikowsi S, Halperin A, Jaffe R. A qualitative study of attitudes, beliefs, and practices among 40 undergraduate smokers. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:23–28. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.1.23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, CA:: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee J, Rigotti N. Cigarette use by college students in smoke-free housing: Results of a national study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20:202–207. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Rigotti N, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Increased levels of cigarette use among college students: A cause for national concern. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1673–1678. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Kenford SL, Welsch SK, Smith SS, Fouladi RT, Fiore MC, et al. Prevalence and predictors of transitions in smoking behavior among college students. Health Psychology. 2004;23:168–177. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]