Abstract

Xenoestrogens can affect the healthy functioning of a variety of tissues by acting as potent estrogens via nongenomic signaling pathways or by interfering with those actions of multiple physiological estrogens. Collectively, our and other studies have compared a wide range of estrogenic compounds, including some closely structurally related subgroups. The estrogens that have been studied include environmental contaminants of different subclasses, dietary estrogens, and several prominent physiological metabolites. By comparing the nongenomic signaling and functional responses to these compounds, we have begun to address the structural requirements for their actions through membrane estrogen receptors in the pituitary, in comparison to other tissues, and to gain insights into their typical non-monotonic dose-response behavior. Their multiple inputs into cellular signaling begin processes that eventually integrate at the level of mitogen-activated protein kinase activities to coordinately regulate broad cellular destinies, such as proliferation, apoptosis, or differentiation.

Keywords: xenoestrogen, membrane estrogen receptors, signaling

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals such as xenoestrogens are known to contaminate our environment and affect the reproductive health of animals and probably humans (Singleton and Khan, 2003). We and others (e.g., Otto et al., 2008) have studied a variety of subclasses of these compounds to explore understudied mechanistic pathways and receptors that they might engage to mediate their effects. These compounds either may act as inappropriate estrogens and/or could interfere with the actions of endogenous estrogens. Many disease susceptibilities (e.g., involving heart, brain, bone, or joints) worsen or change in women after menopause (Benedetti et al., 2001; Compton et al., 2002; Dluzen and Mickley, 2005; Foltynie et al., 2005; Kurlan, 1992; Mao et al., 2009; Quinn, 2005; Yoon et al., 2007) or at other life stages with different estrogen metabolite profiles, suggesting a differential protective or vulnerability effect due to different physiological estrogen metabolite levels. Therefore, interference by any of the xenoestrogens with these life stage–specific hormonal profiles may cause or alleviate stage-specific diseases in women. Because men also have these estrogen metabolites and receptors to bind to them, xenoestrogens are also likely to alter male physiology (Carreau and Levallet, 2000; Delbes et al., 2006).

Because many xenoestrogenic compounds bioaccumulate in fat tissues, resulting in prolonged and escalating human exposures, the exposure levels causing possible deleterious health effects are somewhat difficult to determine and are actively debated (Myers et al., 2009; Whitten and Patisaul, 2001). Although physiological estrogens can normally influence the growth and functioning of both female and male reproductive, skeletal, and cardiovascular systems (Cornwell et al., 2004), prolonged estrogen exposures have also been linked to the development of cancer in tissues, such as breast, colon, and pituitary (Brownson et al., 2002; Fritz et al., 1998; Mueller and Gooren, 2008). It is thus important to determine which of these estrogenic attributes are shared by xenoestrogens, and via which cellular mechanism(s) they operate, so that their suspected effects on health can be predicted, prevented, perhaps remediated, or even used therapeutically, such as in the case of phytoestrogens (Adlercreutz, 1995).

In the past, xenoestrogenic compounds have undergone extensive testing for actions via nuclear estrogen receptor–mediated gene transcription but have largely been found to act very weakly, if at all, via these genomic pathways (generally at least 1000-fold more weakly than estradiol [E2]). We have instead probed the ability of different classes and structurally variant estrogens to trigger signal cascades initiated at the plasma membrane via membrane estrogen receptors (α, β, and GPR30). To link these effects to the presence of specific receptor subtypes, our laboratory has demonstrated the importance of a membrane form of the estrogen receptor-α (mERα) in clonal rat pituitary cell lines that naturally express high or low receptor levels (Pappas et al., 1994); mERα was also the predominant receptor through which effects were mediated in neuronal cells, although the other estrogen receptors mERβ and GPR30 (Filardo and Thomas, 2005; Revankar et al., 2005) had inhibitory roles (Alyea and Watson, 2009a; Alyea et al., 2008). We also linked E2’s and xenoestrogens’ abilities to mediate membrane-initiated signaling via Ca++ elevation, prolactin (PRL) release, and various kinase activations to complex cellular events, such as cell proliferation and apoptosis (Jeng and Watson, 2009; Zivadinovic et al., 2005). Others have likewise found that specific estrogen receptor subtypes can mediate effects of xenoestrogens (Kuiper et al., 1998; Nadal et al., 2009). Xenoestrogen-altered responses could explain a variety of exposed tissue malfunctions, including both short-term functional deficits and long-term changes in cell and tissue activities (such as teratogenesis and cancer).

TISSUE-SELECTIVE ACTIVITIES

Human exposures to xenoestrogens have been associated with a variety of reproductive and neurological impairments (reviewed in Colborn, 2004; Hotchkiss et al., 2008; McKinlay et al., 2008). The actions of estrogens that we have compared in our own laboratory were largely in cultured cells representing anterior pituitary lactotrophs (Pappas et al., 1994). In the pituitary, estrogens facilitate both synthesis and regulated secretion of PRL (Dannies, 1985) and other peptide hormones, but we have focused on those actions that happen rapidly in response to estrogens—the secretory response. To understand to what kinds of pathologies these actions may be related, we must review the numerous roles of PRL. PRL coordinates the female hormonal cycle with preparation of tissues (e.g., mammary gland) for reproduction and the control of reproductive behavior. Hyperprolactinemia is a recognized cause of infertility as well as behavioral illnesses. Exaggerations in pregnancy behaviors and also in pseudopregnancy (where PRL levels rise without a pregnancy) include maternal behavior aggressiveness and sexual dysfunction. PRL overstimulation can also be correlated with depression, changed affect, and abnormal responses to stress (Sobrinho, 2003).

Estrogen-induced cell proliferation is part of the normal response of the pituitary but can also produce pituitary tumors (Gorski et al., 1997). PRL is believed to be a growth factor for many target tissues, including breast and prostate (Adams, 1992; Nevalainen et al., 1997), so its overproduction may lead to pathologies or tumors of these tissues (Clevenger et al., 2003; Gutzman et al., 2004; Rose-Hellekant et al., 2003). If any xenoestrogens act differently than the normal timing and levels of endogenous estrogens, then imbalances of PRL secretion and stimulation could occur; these could be developmental stage specific or gender specific and might cause unanticipated harmful responses. Our studies demonstrated how this could occur mechanistically for different estrogens and xenoestrogens via membrane-initiated signaling pathways (Bulayeva and Watson, 2004; Jeng and Watson, 2009; Jeng et al., 2009; Kochukov et al., 2009; Watson et al., 2008).

Estrogen mimetics and antagonists have long been noted to have selective estrogen receptor modulation effects, such as those responding differently in different tissues but via the same receptor (Azuma and Inoue, 2004), usually explained by alternative associations with such transcription factor co-modulators as histone acetyl transferases and histone deacetylases (Liu and Bagchi, 2004). Xenoestrogens appear to be SmERMs, i.e., they are selective membrane estrogen receptor modulators. We and others have demonstrated that these selective effects could result from alternative partnering with other signaling proteins in different tissues or regulatory circumstances (Alyea and Watson, 2009b; Boonyaratanakornkit et al., 2001; Song et al., 2005). As different tissue and cell types are explored for activities in the nongenomic signaling pathway with these different xenoestrogens, tissue-selective profiles will emerge for nongenomic responses such as those we have seen for pituitary cancer cells (Bulayeva and Watson, 2004; Jeng et al., 2009; Wozniak et al., 2005), breast cancer cells (Zivadinovic and Watson, 2005; Zivadinovic et al., 2005), cells of the immune system (Narita et al., 2007), and neuronal cell types (Alyea and Watson, 2009a), and others have seen for bone versus mammary tissues (Otto et al., 2008). This should help to explain their toxicities.

STRUCTURALLY RELATED SUBCLASSES OF ESTROGENS AND THEIR ACTIVITIES

Over the past decade or so, our laboratory has examined several subgroups of estrogens with different potentials for promoting or interfering with estrogenic actions via signaling at the cell membrane. The 16 compounds that we have investigated so far (see Fig. 1) represent either structurally related subgroups (endogenous hormone metabolites, alkylphenols, chlorinated pesticides, soy isoflavones) or are related via their use and exposure route (dietary vs. endogenous metabolites vs. environmental contaminants from industry, agriculture, or consumer products). Considering them together, let us begin exploring the structural requirements for nongenomic estrogenic signaling via different pathways. Collectively, we and others have learned that estrogens originally deemed “weak” for their actions in the nucleus can potently activate nongenomic signaling pathways (Alyea and Watson, 2009a,b; Bouskine et al., 2009; Bulayeva and Watson, 2004; Jeng and Watson, 2009; Jeng et al., 2009; Kochukov et al., 2009; Nadal et al., 2009; Otto et al., 2008; Watson et al., 2007, 2008). It is also clear that the rules for engagement via membrane-initiated estrogen actions for various signaling cascades differ.

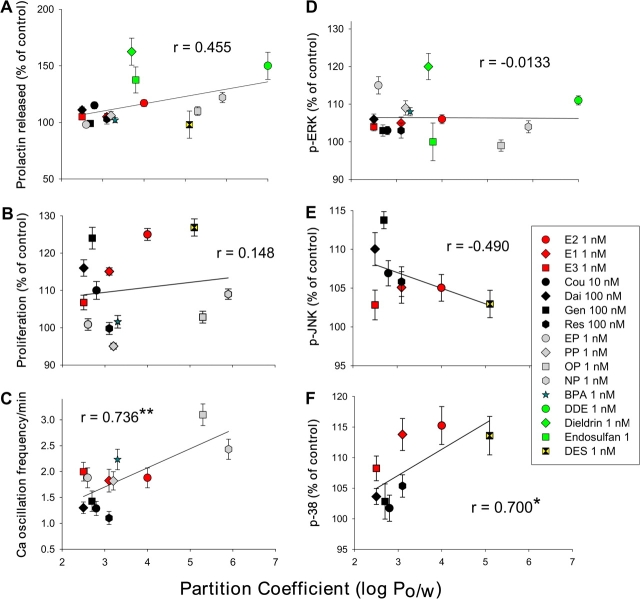

FIG. 1.

Structural comparison between classes of estrogens grouped by use or route of exposure. Shown are several physiological estrogens, including the most frequently studied 17β-estradiol and several of its metabolites, a pharmaceutical mimic (diethylstilbestrol, DES), dietary phytoestrogens, and two classes of environmental estrogens (including dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene, DDE).

While E2 is the physiological estrogen most often studied and associated with reproductive function during the reproductive years, other endogenous estrogenic compounds can be more prevalent during other life phases. These other estrogens may have significant effects on tissue development, function, and disease states (such as the development of cancers in reproductive tissues). Estrone (E1) is a significant estrogenic hormone contributor in both reproductive (∼0.5–1nM) and postmenopausal (150–200pM) women and in men (∼100pM); estriol (E3) levels are significantly higher in pregnant women (∼10–100nM) than in nonpregnant women (< 7nM) (Greenspan and Gardner, 2004). Lowered E3 levels in pregnancy have been associated with complications of eclampsia (Shenhav et al., 2003) and the incidence of Down’s syndrome in offspring (Chard and Macintosh, 1995). These estrogenic metabolites are also produced by aromatases in a number of nonreproductive tissues where their effects may extend beyond reproductive functions (Meinhardt and Mullis, 2002). One example is that E3 has protective effects against the development of arthritis in certain experimental models (Jansson and Holmdahl, 2001), as has been known previously for E2. Effects in brain, bone, cardiovascular system, and many other tissues may be affected differentially by these three endogenous estrogenic compounds during different life stages; therefore, loss or enhancement of these effects due to interference by xenoestrogenic compounds could affect human health in a large number of tissues. These metabolites also present an interesting structure-activity study group as their modifications are simple variations at only two positions on their D-rings (see Fig. 1). Scant previous information about the actions of physiological concentrations of E1 and E3 via nongenomic steroid signaling mechanisms (Morley et al., 1992; Selles et al., 2005) have now been augmented by our recent studies (Alyea and Watson, 2009b; Watson et al., 2008). We saw that E1 and E3 were similarly potent with E2 in some responses for both pituitary cells (increasing the number of Ca++-responding cells and evoking extracellular-regulated kinase [ERK] phosphorylation) and neuronal cells (evoking dopamine efflux). However, in neuronal cells, E1 and E3 (inhibitory) had opposite effects from E2 (stimulatory) on the activation of dopamine efflux by the dopamine transporter (DAT), and these physiological hormones achieved this by differentially causing rapid trafficking of the estrogen receptors (α, β, and GPR30) and DAT to and from the plasma membrane. Further exploration of these potent and differential effects of physiological estrogen metabolites, and interference with their activities by xenoestrogens, could illuminate other life stage–specific changes in estrogen-related disease vulnerabilities.

Alkylphenols represent a group of ubiquitous environmental estrogens that are highly related in structure, although somewhat different from E2. These compounds are surfactants or monomer byproducts of plastic manufacturing or product breakdown. They have been found at surprisingly high concentrations in human fluids (Lakind and Naiman, 2008; Stahlhut et al., 2009) and at environmental sites (Kolpin et al., 2002; Talsness et al., 2009; Thomas and Doughty, 2004). Our laboratory compared several members of this class with either different lengths of carbon side-chain modifications at Position 4 on the phenol ring (nonyl-, octyl-, propyl-, and ethylphenol [NP, OP, PP, EP]; see Fig. 1), or instead an added phenolic group (bisphenol A [BPA]). These compounds were active at very low doses in our studies (Kochukov et al., 2009), a potency confirmed by others studying other endocrine tissues (Alonso-Magdalena et al., 2008; Nadal et al., 2009). These comparisons represent low environmentally common concentrations (femtomoles to nanomoles). Overall, the alkylphenols are quite potent in several of our assays for nongenomic responses, including PRL release, cell proliferation, calcium (Ca++) influx, and in the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAP kinases) (Bulayeva and Watson, 2004; Kochukov et al., 2009; Wozniak et al., 2005). These activities are summarized for all our publications to date in Figure 2.

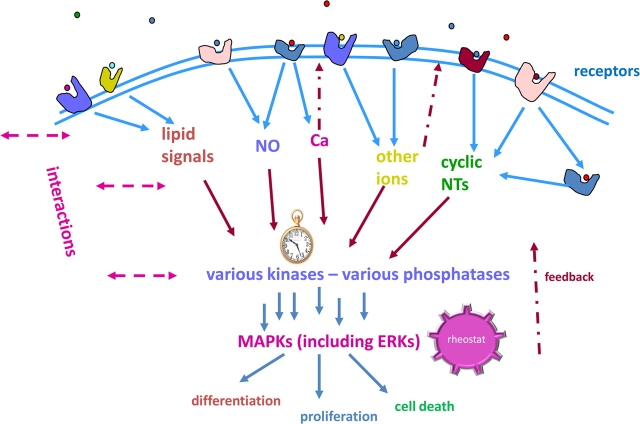

FIG. 2.

Structure-activity analysis of estrogens based on lipophilicity. The assays involved are described in Kochukov et al. 2009. All these signaling or functional responses to estrogens were graphed versus their octanol/water partition coefficient (log Po/w) (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2009) to determine if their lipophilicity profiles predicted their effectiveness as an estrogen. Different signaling or functional responses are shown in each panel: (A) PRL release, (B) cell proliferation, (C) Ca++ peak oscillation frequency, (D) ERK activation, (E) Jun-kinase (JNK) activation, and (F) p38 kinase activation. Low physiologically or environmentally relevant concentrations for all compounds used in A, B, and D–F are shown in the composite symbol legend. In the case of the calcium response (C), data from all effective concentrations were included (femtomoles to nanomoles for alkylphenols and physiological estrogens and 0.1nM–0.1μM for phytoestrogens) because the responses were “all or none” and not graded according to concentration. All response patterns were used to calculate a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) to describe the degree of correlation, either positive or negative, with the lipophilicity of the ligands. *Very close to being statistically significant, p = 0.0533. **Statistically significant, p < 0.01. For panel A, p = 0.0767 and for panel E, p = 0.218. Panels B and D have quite high p values, which do not indicate any significance. Cou, Coumestrol; Dai, daidzein; Gen, genistein; Res, resveratrol; PP, propylphenol; NP, nonylphenol; BPA; DES, diethylstilbestrol.

By comparison, BPA and nonylphenol have shown very low potency in nuclear transcription assays for estrogen-responsive genes (Gaido et al., 1997; Gutendorf and Westendorf, 2001; Kloas et al., 1999; Sheeler et al., 2000; Singleton et al., 2004; Steinmetz et al., 1997). The long carbon side-chain alkylphenols were previously shown to have weak estrogenic activity in genomic assays, and the shorter side-chain versions were even less active (Kwack et al., 2002; Routledge and Sumpter, 1997; Tabira et al., 1999). In contrast, their nongenomic activities are quite robust, and short or long carbon chain variants are more effective in different responses (Kochukov et al., 2009). Therefore, inactivity in genomic assays does not predict inactivity in nongenomic mechanisms. In addition, this class of xenoestrogens is becoming increasingly important to consider for further modification by chlorination in manufacturing and waste water treatment plants (Fukazawa et al., 2001; Gallard et al., 2004; Gross et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2002; Petrovic et al., 2003), so structure-activity knowledge about their estrogenic effects will become increasingly important.

Our laboratory has also performed nongenomic signaling studies with several chlorinated pesticides known to be estrogenic—dieldrin, dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene, and endosulfan. These compounds break down slowly, and so persist in the soil even though their use has largely been banned (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005). Plants and animals that are part of the food supply become exposed, subsequently passing on these exposures to humans. Because many xenoestrogens bioaccumulate in fat tissues, resulting in prolonged and escalating human exposures, the exposure levels causing deleterious health effects are actively debated (Myers et al., 2009). In our studies, these chlorinated xenoestrogen pesticides were quite effective in eliciting all the responses examined, including ERK activation (Bulayeva and Watson, 2004), PRL release, and Ca++ influx (Wozniak et al., 2005). The studies of others have also demonstrated rapid signaling actions of these compounds on endocrine cells (Wu et al., 2006).

Phytoestrogens, another category of nonphysiological estrogens, have diverse estrogenic biological activities due in part to their ability to act as either estrogen agonists or antagonists depending on the dose and the specific tissue involved. These abilities have caused a lot of attention to be focused on these compounds as potential safe, effective, and inexpensive estrogen replacement medications. Coumestrol, first reported to be estrogenic when it was associated with disrupting reproduction in livestock (Bickoff et al., 1957), is found in such dietary sources such as legumes, clover, and sprouts of soybeans and alfalfa. The reported serum concentration resulting from ingesting these foods in humans is approximately 0.01μM (Mustafa et al., 2007). Isoflavones are represented in our studies by daidzein and genistein, and their major source is soy-based foods. In Asia, the intake of soy is high, and plasma concentrations of genistein from 0.1 to 10μM have been measured (Mustafa et al., 2007; Whitten and Patisaul, 2001); Western diets usually contain about 10-fold lower concentrations (Adlercreutz et al., 1993). Some isoflavones, such as genistein, have also been shown to act predominantly via estrogen receptor-β in genomic responses (Kuiper et al., 1998). Trans-resveratrol, a stilbene (Gehm et al., 1997) that has recently attracted significant attention as a potential anti-aging agent, is found in high quantities in foods such as red grapes (or wine) and peanuts and has peak serum concentrations estimated to be close to 2μM in humans (Walle et al., 2004).

To rank the effectiveness of all these compounds together and to examine one chemical feature of xenoestrogens thought to facilitate their behavior as estrogens, we graphed their responses according to each compound’s lipophilicity (Fig. 2). We chose an octanol-water partition coefficient to numerically represent this value for graphing. We combined the results on compounds from different classes of estrogens and xenoestrogens, gleaned from a number of our studies, so as to compare their lipophilicity to their estrogenicity at multiple end points in the nongenomic pathway. Depending on the signaling or functional end point being assessed, the lipophilicity value positively influenced (PRL release, Ca++ oscillation frequency, and p38 activity), negatively influenced (Jun-Kinase [JNK] activity), or did not influence (proliferation and ERK activity) a response parameter. Also, not influenced by lipophilicity (data not shown) was the total amount of Ca++ influx (combined peak areas, correlation coefficient of r = 0.0015). Therefore, lipophilicity is one characteristic of xenoestrogens that can partially predict some aspects of estrogenicity. There are undoubtedly other aspects of these chemicals’ structures that will need to be evaluated in the future for their contributions to such predictions. It is not surprising that for different end points, estrogens can have positive influence, negative influence, or no influence. Estrogen receptors liganded by a given estrogen will create specific shape changes in the receptor, resulting in a different constellation of interaction surfaces (Pike et al., 1999) to which other proteins can bind. Partner proteins may be activated or further recruit other proteins, leading to a given functional response.

NON-MONOTONIC DOSE RESPONSES, SUMMATION, AND INTEGRATION OF RESPONSES

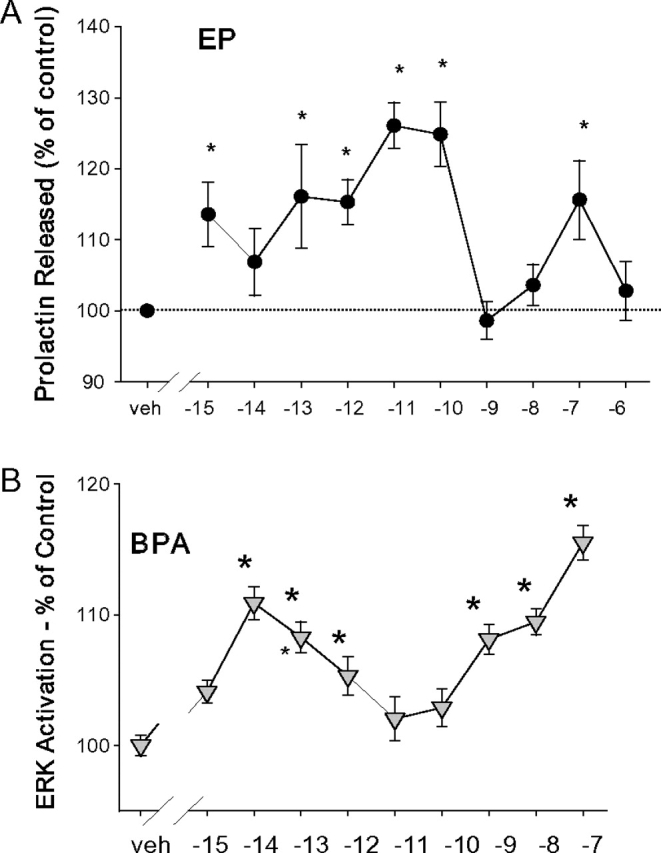

Nongenomic estrogenic responses often display non-monotonic dose-response characteristics (Weltje et al., 2005) (dose curves that do not follow the principle of low-dose effects rising from a threshold and plateauing at higher concentrations). Response decay at higher steroid concentrations (∩-shaped curves) has been a curious feature long noted for genomic and whole-animal functional responses (Welshons et al., 2003). Non-monotonic dose-response curves studied in our laboratory for rapid nongenomic responses to estrogens not only reverse direction at higher doses but sometimes rise and decline multiple times with increasing dose over a wide concentration test range (perhaps representing two ∩-shaped curves put together). Such dose relationships make it impossible to extrapolate high-dose effects to predict low-dose effects. Since much toxicological regulatory policy is based on putative monotonic dose relationships, toxicants that mimic the non-monotonicity characteristic of hormone effects have important ramifications for the regulation of compounds such as environmental estrogens. We have probably been able to observe these responses to very low levels of hormones and mimetics in our studies because of our ability to manipulate cells in culture to exclude endogenous hormone sources entirely (defined media and exhaustively steroid-stripped media). Examples of two such responses to environmental estrogens demonstrating this non-monotonic characteristic from our own work are shown in Figure 3. EP, an alkylphenol, is shown here to cause rapid PRL release at very low concentrations and at higher concentrations but reverses this response at intermediate concentrations. BPA elicits a similar behavior in one example of MAP kinase responses—ERK phosphorylation. The shapes of these dose-response curves are similar to those we have observed for both physiological and a variety of nonphysiological estrogens (Alyea and Watson, 2009a; Bulayeva and Watson, 2004; Jeng and Watson, 2009; Jeng et al., 2009; Kochukov et al., 2009; Watson et al., 1999, 2008; Wozniak et al., 2005; Zivadinovic et al., 2005).

FIG. 3.

Examples of non-monotonic dose responses reproduced from Kochukov et al. 2009. (A) Concentration dependence of EP-induced rapid changes in PRL secretion. PRL released into the medium was measured by radioimmunoassay after 1 min of treatment with EP at different concentrations (n = 12–24 for each data point over three experiments). (B) Concentration-dependent changes in the phosphorylation status of ERKs 1 and 2 after 5-min BPA treatments. Values are the amount of dephosphorylated p-nitrophenol generated by an alkaline phosphatase–tagged ERK antibody normalized to the crystal violet staining value for cell number for each well, presented as a percentage of vehicle-treated controls (veh). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle control (n = 32 samples for each data point over four experiments).

We have speculated that such typical bimodal dose responses for these membrane-initiated mechanisms could result from different receptor subpopulations present in unique compartments of the plasma membrane. For example, membrane forms of steroid receptors have also been shown to reside in membrane caveolae by us (Zivadinovic and Watson, 2005) and others (Chambliss and Shaul, 2002; Lu et al., 2001; Norman et al., 2002), where it is well known that lipid content and other signaling molecule and scaffolding protein availability are quite different from non-raft membranes. Basolateral versus apical or endocytosed membrane compartments represent compartments of different accessibility for hormones to their receptors (Cao et al., 1998), although this is less likely to be the case for small lipophilic molecules like steroids or their mimetics than for peptide hormones. Subcellular location–based availabilities could also dictate different physical associations with other proteins by altering hormone-binding and -partnering opportunities. In addition, differences in lipid content simulated in artificial membranes are known to affect the functioning of proteins imbedded therein (Wu and Gorenstein, 1993), likely causing alteration of ligand-binding pockets and protein partner interaction interfaces. Therefore, characteristics of receptors that target to the membrane or membrane subcompartments may affect signaling responses.

We also know from our own work that estrogens, including xenoestrogens, can signal via several different pathways simultaneously although differentially and that these signals traverse their pathways at variable speeds (Bulayeva and Watson, 2004). Different phasing of pathway travel, along with feedback or feedforward regulation or crossing over to parallel paths, can result in complex contributions to dose-response changes, not obvious when examined at a single time point. An example could be the estrogenic activation of a phosphatase, which then inactivates another protein, such as a kinase; if the response being monitored is the kinase activation, then one would see an unexpected decline in the response whenever the phosphatase has been activated. We have some evidence for this effect on response curves in breast cancer cells (Zivadinovic and Watson, 2005 and Banga and Watson, unpublished data). For nuclear receptor actions, it is known that there are different dose-response sensitivities to the same level of nuclear steroid receptor for different genes in the same tissue (Catterall et al., 1985; Simons, 2008), probably also involving receptors partnering with other receptors or coregulators that are target gene specific. Ligand-induced conformations of nuclear receptors can vary due to the structure and level of the hormones bound to them, likely altering their interaction interfaces being presented to other regulatory molecules, thus initiating different responses (Pike et al., 1999). Such mechanisms are also likely to account for associations that regulate membrane-initiated signaling cascades.

Many more examples of nonconventional dose responses will likely be found owing to advances in cell culture and assessment methods for such studies. Our increased understanding of responses to very low concentrations of these ligands demonstrates that animal cells can be extraordinarily sensitive to estrogens. We now use more effective methods for removing other active molecules from culture media (Cao et al., 2009; Wilkinson, 1993) without disturbing the osmolality and protein content milieu needed for normal cell signaling and regulation (Campbell et al., 2002). Completely defined media are now becoming much more available so that cells can be treated with very small known quantities of signaling ligands without interference from endogenous serum-resident steroids and other molecules that can mask responses. Quantitative assays for phosphorylated signaling proteins make detection of small changes at low concentrations more easily defined as significant compared to immunoblot technologies (Bulayeva et al., 2004; Howells et al., 2008; Versteeg et al., 2000). These advances made it possible to do much more comprehensive dose-response analyses, encompassing the low physiological or disease-relevant concentration ranges of steroids and their mimetics. Single-cell analysis methods (e.g., for Ca++ responses) allow detection of responses that would otherwise be masked by unresponsive cells in the same culture; cell expression levels for mERα that control their responsiveness to estrogens are heterogenous at any given time point (Kochukov et al., 2009; Wozniak et al., 2005) due to cell cycle changes and other forms of cellular regulation (Campbell et al., 2002). The “lower hump” of the “camelback” non-monotonic dose-response curve (see Fig. 3) is only recently being examined and appreciated.

FINAL COMMON PATHWAYS AND BROAD CELLULAR IMPERATIVES

In the past, we have most often studied signaling mechanisms one pathway at a time. However, an overview of the accumulated data and powerful new genome-wide assessment technologies have taught us that the regulation of cellular function is more realistically depicted by a convergence of information delivered via many pathways, yet with pathway-selective use by some ligands (Michel and Alewijnse, 2007). Recently, the study of the nongenomic actions of multiple xenoestrogens has made a particularly striking example of this new point of view as these compounds activate many parallel pathways at once, yet selectively with respect to timing and predominant use of these different signaling avenues (Bulayeva and Watson, 2004). These considerations also are important as we contemplate the multiplicity of estrogens we are exposed to at any given time and the effect of the combination of them on signaling outcomes.

The changing circumstances to which a cell must respond are first presented by the ligands that it encounters at its surface, of which there are many that arrive simultaneously. The engagement of surface receptors by these ligands sets in motion coordinated actions, eventually leading to major cellular decision points: proliferation, differentiation, or death. Cells must integrate all these incoming signals and parallel pathways that can eventually contribute to a final common pathway, such as those involving MAP kinases (see Fig. 4). These enzymatic “signal-receiving stations” tally up many inputs from multiple signaling cascades and sum them toward establishing a level of end point of MAP kinase (ERK, JNK, and p38) activities. The final count dictates a decision about how to regulate major cellular responses that require coordination so that the whole cell “is on the same page” during major cellular responses to change. Acting via their membrane receptors, steroids can be one class of input signals to the MAP kinase signal integrator, the cellular rheostat that is dialed up or down according to which pathways feed into it. Not all estrogens elicit identical responses (in level or timing) along these pathways (Bulayeva et al., 2004). Thus, different endogenous metabolites (representing different life-stage challenges) or xenoestrogen mimetic exposures will cause a different tally and resulting cellular response. Estrogens provide a very illustrative example of these cellular strategies because of the availability of many different and medically/environmentally important estrogens that make differential use of the same pathways. This example thus gives new insights into how such signaling webs can lead to variant outcomes depending on which estrogens engage them.

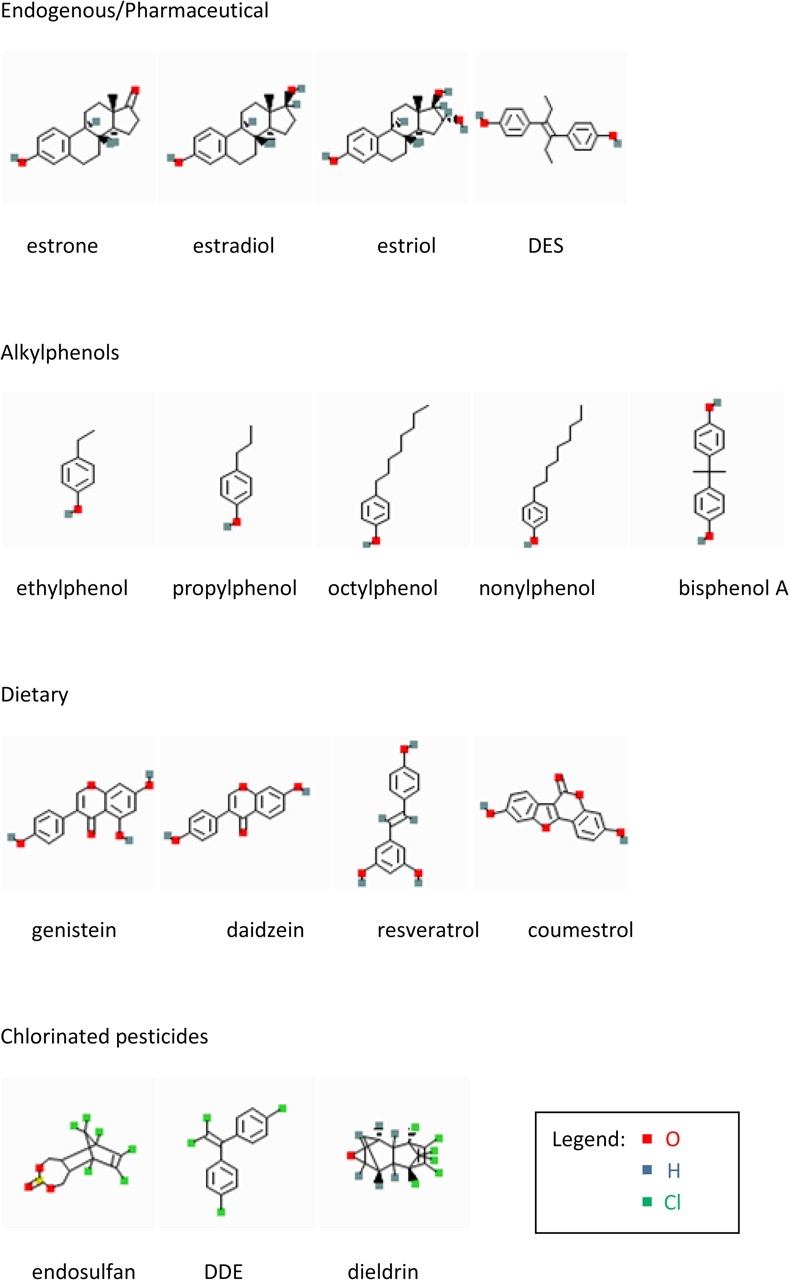

FIG. 4.

Receptors of various types elicit overlapping signals that are summed up in the phosphorylation state of MAP kinases (MAPKs). Various receptors, both on the membrane and inside the cell (including different subtypes of estrogen receptors), generate multiple second messengers (blue arrows), which then trigger functional responses or activate other kinases involved in cellular functions (red arrows). The pocket watch symbol indicates that the timing of these signals differs and can be disrupted. The rheostat knob symbol indicates that some downstream kinase systems (such as the MAPKs) can sum many upstream signals to dial the final signal up or down. MAPK activity can then lead to major cellular functional decisions (differentiation, proliferation, and death). These signaling system interactions are highly complex, and each tissue may present a different repertoire of these machineries and outcomes. Xenoestrogens may participate via various estrogen receptors in multiple cellular locations. NO, nitric oxide; NTs, nucleotides.

SUMMARY

New layers of detail in the workings of estrogen mimetics through nongenomic pathways are being revealed, including characteristics of their unusual dose responses, and specific subclasses of xenoestrogens whose structure-activity relationships can be compared. We are learning how these compounds are different or similar to physiological estrogens when acting at membrane estrogen receptors. While the lipophilicity of these compounds can predict some of their signaling capabilities, there are clearly other structural features that dictate other aspects of the diverse signaling responses these compounds elicit. We have presented examples that show how such understanding of estrogenic or xenoestrogenic ligands may allow us to determine their estrogenic or antiestrogenic potential and use this knowledge to design or prioritize intervention opportunities.

FUNDING

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01 ES015292 to C.S.W.); NIDA (P20 DA024157 to C.S.W.); American Institute for Cancer Research (06A126 to C.S.W.).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr David Konkel for expert editorial assistance for this review.

References

- Adams AB. Human breast cancer: concerted role of diet, prolactin and adrenal C19-delta 5 steroids in tumorigenesis. Int. J. Cancer. 1992;50:854–858. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlercreutz H. Phytoestrogens: epidemiology and a possible role in cancer protection. Environ. Health Perspect. 1995;103(Suppl. 7) doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s7103. 103–112. (Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlercreutz H, Fotsis T, Lampe J, Wahala K, Makela T, Brunow G, Hase T. Quantitative determination of lignans and isoflavonoids in plasma of omnivorous and vegetarian women by isotope dilution gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. Suppl. 1993;215:5–18. doi: 10.3109/00365519309090693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Magdalena P, Ropero AB, Carrera MP, Cederroth CR, Baquie M, Gauthier BR, Nef S, Stefani E, Nadal A. Pancreatic insulin content regulation by the estrogen receptor ER alpha. PLoS. One. 2008;3:e2069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alyea RA, Laurence SE, Kim SH, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA, Watson CS. The roles of membrane estrogen receptor subtypes in modulating dopamine transporters in PC-12 cells. J. Neurochem. 2008;106:1525–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alyea RA, Watson CS. Differential regulation of dopamine transporter function and location by low concentrations of environmental estrogens and 17beta-estradiol. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009a;117:778–783. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alyea RA, Watson CS. Nongenomic mechanisms of physiological estrogen-mediated dopamine efflux. BMC Neurosci. 2009b;10:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma K, Inoue S. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: mechanisms of action and their tissue selectivity. Clin. Calcium. 2004;14(10):12–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti MD, Maraganore DM, Bower JH, McDonnell SK, Peterson BJ, Ahlskog JE, Schaid DJ, Rocca WA. Hysterectomy, menopause, and estrogen use preceding Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory case-control study. Mov. Disord. 2001;16:830–837. doi: 10.1002/mds.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickoff EM, Booth AN, Lyman RL, Livingston AL, Thompson CR, Deeds F. Coumestrol, a new estrogen isolated from forage crops. Science. 1957;126:969–970. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3280.969-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonyaratanakornkit V, Scott MP, Ribon V, Sherman L, Anderson SM, Maller JL, Miller WT, Edwards DP. Progesterone receptor contains a proline-rich motif that directly interacts with SH3 domains and activates c-Src family tyrosine kinases. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:269–280. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouskine A, Nebout M, Brucker-Davis F, Benahmed M, Fenichel P. Low doses of bisphenol A promote human seminoma cell proliferation by activating PKA and PKG via a membrane G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117:1053–1058. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson DM, Azios NG, Fuqua BK, Dharmawardhane SF, Mabry TJ. Flavonoid effects relevant to cancer. J. Nutr. 2002;132(Suppl. 11):3482S–3489S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3482S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulayeva NN, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Quantitative measurement of estrogen-induced ERK 1 and 2 activation via multiple membrane-initiated signaling pathways. Steroids. 2004;69:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulayeva NN, Watson CS. Xenoestrogen-induced ERK-1 and ERK-2 activation via multiple membrane-initiated signaling pathways. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004;112:1481–1487. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CH, Bulayeva N, Brown DB, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Regulation of the membrane estrogen receptor-alpha: role of cell density, serum, cell passage number, and estradiol. FASEB J. 2002;16:1917–1927. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0182com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao TT, Mays RW, von Zastrow M. Regulated endocytosis of G-protein-coupled receptors by a biochemically and functionally distinct subpopulation of clathrin-coated pits. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:24592–24602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, West C, Norton-Wenzel CS, Rej R, Davis FB, Davis PJ, Rej R. Effects of resin or charcoal treatment on fetal bovine serum and bovine calf serum. Endocr. Res. 2009;34:101–108. doi: 10.3109/07435800903204082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreau S, Levallet J. Testicular estrogens and male reproduction. News Physiol. Sci. 2000;15:195–198. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.4.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall JF, Watson CS, Kontula KK, Janne OA, Bardin CW. Molecular Mechanisms of Steroid Hormone Action (V. K. Moudgil, Ed.) New York: Walter de Gruyter; 1985. Differential sensitivity of specific genes in mouse kidney to androgens and antiandrogens; pp. 587–602. [Google Scholar]

- Chambliss KL, Shaul PW. Rapid activation of endothelial NO synthase by estrogen: evidence for a steroid receptor fast-action complex (SRFC) in caveolae. Steroids. 2002;67:413–419. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(01)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chard T, Macintosh MC. Screening for Down’s syndrome. J. Perinat. Med. 1995;23:421–436. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1995.23.6.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger CV, Furth PA, Hankinson SE, Schuler LA. The role of prolactin in mammary carcinoma. Endocr. Rev. 2003;24:1–27. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colborn T. Neurodevelopment and endocrine disruption. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004;112:944–949. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton J, van AT, Murphy D. Mood, cognition and Alzheimer’s disease. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2002;16:357–370. doi: 10.1053/beog.2002.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell T, Cohick W, Raskin I. Dietary phytoestrogens and health. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:995–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannies PS. Control of prolactin production by estrogen. In: Litwack G, editor. Biochemical Actions of Hormones. 12th ed. Orlando, FL: Academic Press, Inc.; 1985. pp. 289–310. [Google Scholar]

- Delbes G, Levacher C, Habert R. Estrogen effects on fetal and neonatal testicular development. Reproduction. 2006;132:527–538. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dluzen DE, Mickley KR. Gender differences in modulatory effects of tamoxifen upon the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2005;80:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Thomas P. GPR30: a seven-transmembrane-spanning estrogen receptor that triggers EGF release. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;16:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltynie T, Lewis SG, Goldberg TE, Blackwell AD, Kolachana BS, Weinberger DR, Robbins TW, Barker RA. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism has a gender specific influence on planning ability in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2005;252:833–838. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0756-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz WA, Coward L, Wang J, Lamartiniere CA. Dietary genistein: perinatal mammary cancer prevention, bioavailability and toxicity testing in the rat. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:2151–2158. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.12.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukazawa H, Hoshino K, Shiozawa T, Matsushita H, Terao Y. Identification and quantification of chlorinated bisphenol A in wastewater from wastepaper recycling plants. Chemosphere. 2001;44:973–979. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(00)00507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaido KW, Leonard LS, Lovell S, Gould JC, Babai D, Portier CJ, McDonnell DP. Evaluation of chemicals with endocrine modulating activity in a yeast-based steroid hormone receptor gene transcription assay. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997;143:205–212. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.8069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallard H, Leclercq A, Croue JP. Chlorination of bisphenol A: kinetics and by-products formation. Chemosphere. 2004;56:465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehm BD, McAndrews JM, Chien PY, Jameson JL. Resveratrol, a polyphenolic compound found in grapes and wine, is an agonist for the estrogen receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:14138–14143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski J, Wendell D, Gregg D, Chun TY. Estrogens and the genetic control of tumor growth. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1997;396 233–243. (Review) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan FS, Gardner DG. Basic and Clinical Endocrinology. New York: Lange Medical Books, McGraw Hill; 2004. pp. 925–926. [Google Scholar]

- Gross B, Montgomery-Brown J, Naumann A, Reinhard M. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceuticals and alkylphenol ethoxylate metabolites in an effluent-dominated river and wetland. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2004;23:2074–2083. doi: 10.1897/03-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutendorf B, Westendorf J. Comparison of an array of in vitro assays for the assessment of the estrogenic potential of natural and synthetic estrogens, phytoestrogens and xenoestrogens. Toxicology. 2001;166(1–2):79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutzman JH, Miller KK, Schuler LA. Endogenous human prolactin and not exogenous human prolactin induces estrogen receptor alpha and prolactin receptor expression and increases estrogen responsiveness in breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;88(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss AK, Rider CV, Blystone CR, Wilson VS, Hartig PC, Ankley GT, Foster PM, Gray CL, Gray LE. Fifteen years after “Wingspread”–environmental endocrine disrupters and human and wildlife health: where we are today and where we need to go. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;105:235–259. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells LM, Neal CP, Brown MC, Berry DP, Manson MM. Indole-3-carbinol enhances anti-proliferative, but not anti-invasive effects of oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer cell lines. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008;75:1774–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JY, Xie GH, Aizawa T. Products of aqueous chlorination of 4-nonylphenol and their estrogenic activity. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002;21:2034–2039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson L, Holmdahl R. Enhancement of collagen-induced arthritis in female mice by estrogen receptor blockage. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2168–2175. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2168::aid-art370>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng YJ, Kochukov MY, Watson CS. Membrane estrogen receptor-alpha-mediated nongenomic actions of phytoestrogens in GH3/B6/F10 pituitary tumor cells. J. Mol. Signal. 2009;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng YJ, Watson CS. Proliferative and anti-proliferative effects of dietary levels of phytoestrogens in rat pituitary GH3/B6/F10 cells—the involvement of rapidly activated kinases and caspases. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:334. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloas W, Lutz I, Einspanier R. Amphibians as a model to study endocrine disruptors: II. Estrogenic activity of environmental chemicals in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Total Environ. 1999;225:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(99)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochukov MY, Jeng Y-J, Watson CS. Alkylphenol xenoestrogens with varying carbon chain lengths differentially and potently activate signaling and functional responses in GH3/B6/F10 somatomammotropes. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117:723–730. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolpin DW, Furlong ET, Meyer MT, Thurman EM, Zaugg SD, Barber LB, Buxton HT. Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in U.S. streams, 1999-2000: a national reconnaissance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002;36:1202–1211. doi: 10.1021/es011055j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Lemmen JG, Carlsson B, Corton JC, Safe SH, van der Saag PT, van der BB, Gustafsson JA. Interaction of estrogenic chemicals and phytoestrogens with estrogen receptor beta. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4252–4263. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurlan R. The pathogenesis of Tourette’s syndrome. A possible role for hormonal and excitatory neurotransmitter influences in brain development. Arch. Neurol. 1992;49:874–876. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530320106020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwack SJ, Kwon O, Kim HS, Kim SS, Kim SH, Sohn KH, Lee RD, Park CH, Jeung EB, An BS, et al. Comparative evaluation of alkylphenolic compounds on estrogenic activity in vitro and in vivo. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2002;65:419–431. doi: 10.1080/15287390252808082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakind JS, Naiman DQ. Bisphenol A (BPA) daily intakes in the United States: estimates from the 2003-2004 NHANES urinary BPA data. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2008;18:608–615. doi: 10.1038/jes.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XF, Bagchi MK. Recruitment of distinct chromatin-modifying complexes by tamoxifen-complexed estrogen receptor at natural target gene promoters in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:15050–15058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu ML, Schneider MC, Zheng Y, Zhang X, Richie JP. Caveolin-1 interacts with androgen receptor. A positive modulator of androgen receptor mediated transactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:13442–13451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao JJ, Stricker C, Bruner D, Xie S, Bowman MA, Farrar JT, Greene BT, Demichele A. Patterns and risk factors associated with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:3631–3639. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay R, Plant JA, Bell JN, Voulvoulis N. Calculating human exposure to endocrine disrupting pesticides via agricultural and non-agricultural exposure routes. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;398:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt U, Mullis PE. The essential role of the aromatase/p450arom. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2002;20:277–284. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel MC, Alewijnse AE. Ligand-directed signaling: 50 ways to find a lover. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;72:1097–1099. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley P, Whitfield JF, Vanderhyden BC, Tsang BK, Schwartz J. A new, nongenomic estrogen action: the rapid release of intracellular calcium. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1305–1312. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1505465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller A, Gooren L. Hormone-related tumors in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2008;159:197–202. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa AM, Malintan NT, Seelan S, Zhan Z, Mohamed Z, Hassan J, Pendek R, Hussain R, Ito N. Phytoestrogens levels determination in the cord blood from Malaysia rural and urban populations. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2007;222:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JP, Zoeller RT, vom Saal FS. A clash of old and new scientific concepts in toxicity, with important implications for public health. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009 doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900887. (Forthcoming) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal A, Alonso-Magdalena P, Soriano S, Quesada I, Ropero AB. The pancreatic beta-cell as a target of estrogens and xenoestrogens: implications for blood glucose homeostasis and diabetes. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2009;304:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita SI, Goldblum RM, Watson CS, Brooks EG, Estes DM, Curran EM, Midoro-Horiuti T. Environmental estrogens induce mast cell degranulation and enhance IgE-mediated release of allergic mediators PMCID: 17366818. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115:48–52. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. 2009. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. (Electronic Citation) [Google Scholar]

- Nevalainen MT, Valve EM, Ingleton PM, Nurmi M, Martikainen PM, Harkonen PL. Prolactin and prolactin receptors are expressed and functioning in human prostate. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:618–627. doi: 10.1172/JCI119204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman AW, Olivera CJ, Barreto Silva FR, Bishop JE. A specific binding protein/receptor for 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is present in an intestinal caveolae membrane fraction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;298:414–419. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto C, Fuchs I, Altmann H, Klewer M, Schwarz G, Bohlmann R, Nguyen D, Zorn L, Vonk R, Prelle K, et al. In vivo characterization of estrogen receptor modulators with reduced genomic versus nongenomic activity in vitro. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008;111(1–2):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas TC, Gametchu B, Yannariello-Brown J, Collins TJ, Watson CS. Membrane estrogen receptors in GH3/B6 cells are associated with rapid estrogen-induced release of prolactin. Endocrine. 1994;2:813–822. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic M, Diaz A, Ventura F, Barcelo D. Occurrence and removal of estrogenic short-chain ethoxy nonylphenolic compounds and their halogenated derivatives during drinking water production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003;37:4442–4448. doi: 10.1021/es034139w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike AC, Brzozowski AM, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Thorsell AG, Engstrom O, Ljunggren J, Gustafsson JA, Carlquist M. Structure of the ligand-binding domain of oestrogen receptor beta in the presence of a partial agonist and a full antagonist. EMBO J. 1999;18:4608–4618. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PO. Treating adolescent girls and women with ADHD: gender-specific issues. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005;61:579–587. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307:1625–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Hellekant TA, Arendt LM, Schroeder MD, Gilchrist K, Sandgren EP, Schuler LA. Prolactin induces ERalpha-positive and ERalpha-negative mammary cancer in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2003;22:4664–4674. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge EJ, Sumpter JP. Structural features of alkylphenolic chemicals associated with estrogenic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:3280–3288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selles J, Polini N, Alvarez C, Massheimer V. Novel action of estrone on vascular tissue: regulation of NOS and COX activity. Steroids. 2005;70:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeler CQ, Dudley MW, Khan SA. Environmental estrogens induce transcriptionally active estrogen receptor dimers in yeast: activity potentiated by the coactivator RIP140. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000;108:97–103. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0010897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav S, Gemer O, Volodarsky M, Zohav E, Segal S. Midtrimester triple test levels in women with severe preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2003;82:912–915. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons SS., Jr What goes on behind closed doors: physiological versus pharmacological steroid hormone actions. Bioessays. 2008;30:744–756. doi: 10.1002/bies.20792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton DW, Feng Y, Chen Y, Busch SJ, Lee AV, Puga A, Khan SA. Bisphenol-A and estradiol exert novel gene regulation in human MCF-7 derived breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2004;221:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton DW, Khan SA. Xenoestrogen exposure and mechanisms of endocrine disruption. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s110–s118. doi: 10.2741/1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobrinho LG. Prolactin, psychological stress and environment in humans: adaptation and maladaptation. Pituitary. 2003;6:35–39. doi: 10.1023/a:1026229810876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song RX, Zhang Z, Santen RJ. Estrogen rapid action via protein complex formation involving ERalpha and Src. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;16:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahlhut RW, Welshons WV, Swan SH. Bisphenol A data in NHANES suggest longer than expected half-life, substantial nonfood exposure, or both. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117:784–789. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz R, Brown NG, Allen DL, Bigsby RM, Benjonathan N. The environmental estrogen bisphenol A stimulates prolactin release in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1780–1786. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.5.5132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabira Y, Nakai M, Asai D, Yakabe Y, Tahara Y, Shinmyozu T, Noguchi M, Takatsuki M, Shimohigashi Y. Structural requirements of para-alkylphenols to bind to estrogen receptor. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;262:240–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talsness CE, Andrade AJ, Kuriyama SN, Taylor JA, vom Saal FS. Components of plastic: experimental studies in animals and relevance for human health. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009;364:2079–2096. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Doughty K. Disruption of rapid, nongenomic steroid actions by environmental chemicals: interference with progestin stimulation of sperm motility in Atlantic croaker. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004;38:6328–6332. doi: 10.1021/es0403662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) 2002 Toxicological profile for aldrin and dieldrin. 2005 Available at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp1.pdf. Accessed December 21, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg HH, Nijhuis E, van den Brink GR, Evertzen M, Pynaert GN, van Deventer SJ, Coffer PJ, Peppelenbosch MP. A new phosphospecific cell-based ELISA for p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), p38 MAPK, protein kinase B and cAMP-response-element-binding protein. Biochem. J. 2000;350(Pt 3):717–722. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walle T, Hsieh F, DeLegge MH, Oatis JE, Jr, Walle UK. High absorption but very low bioavailability of oral resveratrol in humans. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004;32:1377–1382. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Alyea RA, Jeng YJ, Kochukov MY. Nongenomic actions of low concentration estrogens and xenoestrogens on multiple tissues PMCID: 17601655. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2007;274:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Jeng YJ, Kochukov MY. Nongenomic actions of estradiol compared with estrone and estriol in pituitary tumor cell signaling and proliferation. FASEB J. 2008;22:3328–3336. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-107672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Norfleet AM, Pappas TC, Gametchu B. Rapid actions of estrogens in GH3/B6 pituitary tumor cells via a plasma membrane version of estrogen receptor-α. Steroids. 1999;64:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welshons WV, Thayer KA, Judy BM, Taylor JA, Curran EM, vom Saal FS. Large effects from small exposures. I. Mechanisms for endocrine-disrupting chemicals with estrogenic activity. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003;111:994–1006. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltje L, vom Saal FS, Oehlmann J. Reproductive stimulation by low doses of xenoestrogens contrasts with the view of hormesis as an adaptive response. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2005;24:431–437. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht551oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten PL, Patisaul HB. Cross-species and interassay comparisons of phytoestrogen action. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001;109(Suppl. 1) doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s15. 5–20. (Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RF. The effect of charcoal/dextran treatment on select serum components. Art Sci. Tissue Culture. 1993;12(3–4):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak AL, Bulayeva NN, Watson CS. Xenoestrogens at picomolar to nanomolar concentrations trigger membrane estrogen receptor-alpha-mediated Ca2+ fluxes and prolactin release in GH3/B6 pituitary tumor cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:431–439. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Foster WG, Younglai EV. Rapid effects of pesticides on human granulosa-lutein cells. Reproduction. 2006;131:299–310. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Gorenstein DG. Structure and dynamics of cytochrome C in non-aqueous solvents by 2D NH-exchange NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:6843–6850. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon DY, Rippel CA, Kobets AJ, Morris CM, Lee JE, Williams PN, Bridges DD, Vandenbergh DJ, Shugart YY, Singer HS. Dopaminergic polymorphisms in Tourette syndrome: association with the DAT gene (SLC6A3) Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007;144:605–610. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivadinovic D, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Membrane estrogen receptor-alpha levels in MCF-7 breast cancer cells predict cAMP and proliferation responses PMCID: 15642158. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R101–R112. doi: 10.1186/bcr958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivadinovic D, Watson CS. Membrane estrogen receptor-alpha levels predict estrogen-induced ERK1/2 activation in MCF-7 cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R130–R144. doi: 10.1186/bcr959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]